Abstract

Background:

Shortly after the year 2000, randomized trials demonstrated that patients with metastatic colon cancer treated with infusional 5-fluorouracil (5FU)/leucovorin with either oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) or irinotecan (FOLFIRI) had a comparable progression-free survival benefit versus patients who received 5FU/leucovorin alone. Factors associated with the initial receipt of the FOLFOX or FOLFIRI regimen are unknown. Our goal was to investigate the patterns and predictors of use for first-line FOLFOX and FOLFIRI.

Methods:

We used the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End-Results-Medicare linked dataset to identify patients with newly diagnosed stage IV colon cancer between the years 2005–2013 who received either first-line FOLFOX or FOLFIRI. We used logistic regression to assess demographic and clinical predictors for FOLFOX versus FOLFIRI. Survival was compared using Kaplan-Meier models.

Results:

Overall, 3000 (79.3%) patients received FOLFOX, while 785 (20.7%) received FOLFIRI. FOLFOX was associated with later year of diagnosis (odds ratio (OR) 0.67, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.54 to 0.82 for 2011–2013 versus 2005–2007), being female (0.82, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.98), and living in the southern region of the US. FOLFIRI was associated with having a higher comorbidity index (1.33, 95%CI 1.07 to 1.67 for >1 comorbidity score versus 0). There was no survival difference observed between the two treatments.

Conclusion:

The majority of SEER-Medicare patients received FOLFOX and not FOLFIRI as a first line treatment for stage IV colon cancer. Several demographic and clinical factors were associated with the use of each specific regimen. No survival difference was detected for the two groups.

Keywords: FOLFOX, FOLFIRI, SEER-Medicare, colon cancer, Stage IV

Micro-abstract:

In this paper, we examine the demographic and clinical characteristics associated with the use of FOLFOX or FOLFIRI in patients with stage IV colon cancer. FOLFOX is prescribed much more frequently than FOLFIRI as first-line therapy, especially in those who were female and with fewer comorbidities. FOLFOX use is increasing in more recent years.

Introduction

There will be an estimated 140,250 new cases of colon cancer in 2018, with about one-fifth of those cases presenting with metastatic disease1,2. Oxaliplatin, a platinum derivative from the diaminocyclohexane platinum family, has been shown to increase the effectiveness of 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin (5FU/LV). When given by itself, oxaliplatin has an overall response rate of only 10% 3. However, when added to the standard regimen of 5FU/LV, advanced colon cancer patients have a response rate of 53% and a progression-free survival (PFS) of 9 months compared to 5FU/LV alone, which has a response rate of only 22% and a PFS of 6 months4. Similarly, irinotecan, a specific inhibitor of topoisomerase I, when added to the standard regimen of 5FU/LV, also increases the effectiveness of treatment. This combination of irinotecan and 5U/LV provides a progression-free survival of 7 months and an overall response rate of 39% (5FU/LV alone: response rate of 21%, PFS of 4.3 months and overall survival were not statistically different between the groups) 5.

After 5FU/LV, a weekly bolus of 5FU/LV with irinotecan (IFL) was embraced as the standard therapy for metastatic colon cancer patients in the United States5. However, studies in the mid-2000s demonstrated that infusional 5FU was safer, less toxic, and more effective than IFL6,7. In the United States, this led to a shift from bolus 5FU to infusional 5FU combined with oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) as the most commonly administered first-line treatment for metastatic colon cancer8; in some European countries, by contrast, infusional 5FU plus irinotecan (FOLFIRI) was preferred as first-line therapy9.

Phase III trials comparing the two regimens demonstrated that both FOLFOX and FOLFIRI provided similar response rates of 54% to 56%, as well as similar PFS rates of 8 months to 8.5 months, respectively10. The FOLFIRI regimen did produce more adverse side effects, including nausea, diarrhea, and neutropenia. However, FOLFOX patients had a higher likelihood of neuropathy10. Nowadays, with these new treatment strategies, the median overall survival for metastatic colon cancer has improved from 11 months to up to three years11.

In this study, we will compare the use of FOLFOX or FOLFIRI as first-line therapy for patients with stage IV colon cancer. Our hypothesis was that there are identifiable demographic and clinical characteristics of patients and providers associated with the use of one chemotherapy regimen over the other.

Methods

Data sources

We used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare linked database, established by Potosky et al.13, for all analyses. SEER has collected data on cancer cases from locations around the US since 1973. The database contains details on tumor characteristics, demographics, and location of all cases listed within its database. As it collects data from across the US, SEER provides a fairly accurate depiction of overall US demographics. The SEER database can also be linked to Medicare claims files which have information on physician services, various therapies and treatments, as well as other medical services for patients over age 65 in the US. The linked database connects the medical claims files to the demographic and tumor data, which provides a unique and generalizable population-based dataset for patients over age 65 years in the US.

Cohort Definition

We identified stage IV colon cancer patients from the database based on SEER histology and staging codes. We excluded patients whose primary cancer was not colon cancer, as well as any patient who was not enrolled in Medicare parts A and B, or who was a member of a health maintenance organization either 12 months before or after diagnosis. Patients who had mismatched records between SEER and Medicare files or who were under the age of 65 years were similarly excluded. We also excluded anyone diagnosed at autopsy or death certificate.

We then identified from this cohort anyone who received either FOLFOX or FOLFIRI as first-line therapy. As we were interested in the characteristics of patients who received either the FOLFOX or FOLFIRI regimens, we excluded patients who did not receive either treatment regimen as well as those who did not receive 5FU. We also excluded from our study sample those who received XELOX (capecitabine/oxaliplatin) or a fluoropyrimidine alone.

Patient characteristics

Patients included in either the FOLFOX or FOLFIRI group were characterized by their gender, race, year of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, socioeconomic status, region, subsite of the tumor, tumor grade, comorbidity status, residence (in a metropolitan area or not), whether they were treated in a teaching hospital, and whether they received bevacizumab.

Socioeconomic status (SES)

We calculated a SES score based on education level, poverty level, and income level. The variable SES was then stratified into 5 levels from highest to lowest. The levels were based on a formula that pooled these variables together giving each of them an equal weight12.

Comorbidity status

To evaluate the comorbidity of each patient, we used the Charlson Comorbidity Index. The index assigns points to each disease in order to calculate a final score based on the patient medical history. We checked past medical claims and ICD-9 diagnostic codes, in order to assign points and a final score to each patient13.

Chemotherapy use

We determined what chemotherapy treatment was utilized based on Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes. FOLFOX treatment was identified by oxaliplatin, HCPCS codes (‘C9205’, ‘J9263’). FOLFIRI was identified by irinotecan, codes (‘J9206’, ‘C9474’, ‘J9205’) and infusional 5 FU was (‘J9190’,’S3722’). Patients were grouped into either the FOLFOX or FOLFIRI groups based on the first treatment they received.

Statistical analysis

For comparing demographic and diagnostic information, a chi-squared test was used to test statistically significant differences in each delineated category. Categories tested were gender, race, year of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, socioeconomic status, region, primary site of the tumor, tumor grade, whether it was treated in a teaching hospital, comorbidity score, whether they received bevacizumab, and residence (in a metropolitan area or not). A multivariate logistic regression model was used to test the odds a patient would be given FOLFOX versus FOLFIRI for the above variables. We also compared overall survival within various subgroups organized by comorbidity score, tumor site and treatment type using the Kaplan-Meier technique and tested for statistical differences using the log-rank test. SAS software, version 9.4, was used to perform all statistical analyses.

Results

We identified a total of 13,011 patients in the SEER-Medicare database who met inclusion criteria for newly diagnosed stage IV colon cancer. As we were interested in the characteristics of patients who received either the FOLFOX or FOLFIRI regimens, we further excluded patients who did not receive either treatment and also those who did not receive 5FU. The remaining group numbered 3,785 patients, with 3,000 (79.3%) in the FOLFOX group and 785 (20.7%) in the FOLFIRI group. There were 155 patients missing data on whether they were treated at a teaching hospital and 307 patients missing data on their comorbidity status. The respective patients were excluded from the regression analysis (Table 2) and the patients missing their comorbidity status were excluded from the survival curve that was stratified by comorbidity (Figure 1d–f).

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with receipt of FOLFIRI as opposed to FOLFOX for Stage IV colon cancer from 2005–2013 in SEER-Medicare

| Characteristics | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1.00 | |

| Female | 0.82 | 0.69 to 0.98 |

| Age at Diagnosis | ||

| 65 – 69 | 1.00 | |

| 70 – 74 | 1.01 | 0.81 to 1.27 |

| 75 – 79 | 0.83 | 0.65 to 1.06 |

| >= 80 | 1.24 | 0.97 to 1.60 |

| Race | ||

| White | 1.00 | |

| Black | 1.07 | 0.79 to 1.44 |

| Hispanic | 1.12 | 0.57 to 2.20 |

| Other/Unknown | 0.68 | 0.45 to 1.04 |

| Year of Diagnosis | ||

| 2005 – 2007 | 1.00 | |

| 2008 – 2010 | 0.67 | 0.55 to 0.83 |

| 2011 – 2013 | 0.66 | 0.54 to 0.82 |

| SES Rank | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | |

| 1 | 1.10 | 0.82 to 1.48 |

| 2 | 0.93 | 0.67 to 1.30 |

| 3 | 1.08 | 0.81 to 1.46 |

| 4 | 1.10 | 0.80 to 1.51 |

| Region | ||

| East | 1.00 | |

| North Central | 0.74 | 0.54 to 1.01 |

| South | 0.68 | 0.51 to 0.90 |

| West | 1.18 | 0.80 to 1.51 |

| Tumor Primary Site | ||

| Right | 1.00 | |

| Left | 1.12 | 0.94 to 1.35 |

| Other/Unknown | 0.88 | 0.60 to 1.30 |

| Grade | ||

| 1 | 1.00 | |

| 2 | 1.02 | 0.67 to 1.56 |

| 3 | 1.02 | 0.66 to 1.59 |

| Other/Unknown | 1.00 | 0.63 to 1.57 |

| Teaching Hospital or Not | ||

| Yes | 1.00 | |

| No | 0.86 | 0.71 to 1.04 |

| Unknown | 0.73 | 0.46 to 1.15 |

| Metropolitan | ||

| Yes | 1.00 | |

| No | 1.05 | 0.76 to 1.44 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | |

| 1 | 1.25 | 1.02 to 1.53 |

| >=2 | 1.33 | 1.07 to 1.67 |

| Received bevacizumab or not | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 1.28 | 0.95 to 1.71 |

Abbreviations: SES: Socioeconomic status

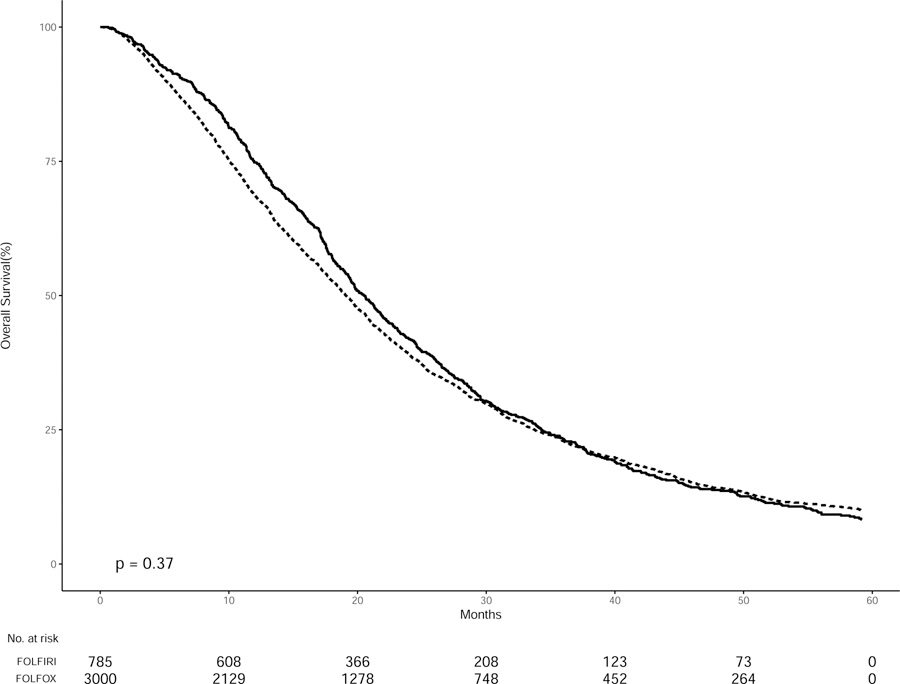

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival in SEER-Medicare patients with Stage IV colon cancer treated with FOLFOX (dashed lines) or FOLFIRI (solid lines) from 2005–2013 stratified by treatment group

Among the 3,785 patients who received either first-line FOLFOX or FOLFIRI, the population was mostly white, male, and urban. This effect was similar in both the FOLFIRI group (56.9% male, 83.0% white, and 91.0% urban) and the FOLFOX group (50.4% male, 82.2% white and 88.1% urban). After excluding patients who were missing their comorbidity status, the analysis revealed significant variation in the cohort based on comorbidity status (p < 0.01), as more patients in the cohort (50.6%) had comorbidity scores of 0 than a comorbidity of 1 (27.4%) or two (22.0%). There was also significant variation in the age of diagnosis (p < 0.01), whether the patient was treated in a teaching hospital (p < 0.007) and the geographic region of treatment across the cohort (p < 0.003). The addition of bevacizumab was consistent between the two treatment groups, as 75% of the FOLFIRI patients and 76% of the FOLFOX patients received bevacizumab along with their treatment.

Notable was the significant variation in the year of diagnosis across the cohort (p < 0.0001). In the FOLFIRI group, 16.2% were diagnosed in 2005, while only 7.9% were diagnosed in 2013. The FOLFOX group was more stable over this time period, varying only by 1–2 percentage points across the years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Receipt of FOLFIRI or FOLFOX for Patients with Stage IV Colon Cancer in SEER-Medicare from 2005–2013

| Variables | FOLFIRI | FOLFOX | Total | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Gender | Male | 447 (56.9%) |

1511 (50.4%) |

1958 (51.7%) |

0.001* |

| Female | 338 (43.1%) |

1489 (49.6%) |

1827 (48.3%) |

||

| 0.3003 | |||||

| Race | White | 653 (83.2%) |

2465 (82.2%) |

3118 (82.4%) |

|

| Black | 85 (10.8%) |

330 (11.0%) |

415 (11.0%) |

||

| Hispanic | 15 (1.9%) |

41 (1.4%) |

56 (1.5%) |

||

| Other/Unknown | 32 (4.1%) |

164 (5.5%) |

196 (5.2%) |

||

| Year of Diagnosis | 2005 | 127 (16.2%) |

332 (11.1%) |

459 (12.1%) |

<0.0001* |

| 2006 | 104 (13.2%) |

307 (10.2%) |

411 (10.9%) |

||

| 2007 | 102 (13.0%) |

298 (9.9%) |

400 (10.6%) |

||

| 2008 | 78 (9.9%) |

356 (11.9%) |

434 (11.5%) |

||

| 2009 | 89 (11.3%) |

340 (11.3%) |

429 (11.3%) |

||

| 2010 | 71 (9.0%) |

385 (12.8%) |

456 (12.0%) |

||

| 2011 | 80 (10.2%) |

341 (11.4%) |

421 (11.1%) |

||

| 2012 | 72 (9.2%) |

314 (10.5%) |

386 (10.2%) |

||

| 2013 | 62 (7.9%) |

327 (10.9%) |

389 (10.3%) |

||

| Age at Diagnosis | 65 – 69 | 218 (27.8%) |

861 (28.7%) |

1079 (28.5%) |

0.0141* |

| 70 – 74 | 243 (31.0%) |

930 (31.0%) |

1173 (31.0%) |

||

| 75 – 79 | 168 (21.4%) |

745 (24.8%) |

913 (24.1%) |

||

| >= 80 | 156 (19.9%) |

464 (15.5%) |

620 (16.4%) |

||

| SES Rank | 0 | 124 (15.8%) |

508 (16.9%) |

632 (16.7%) |

0.352 |

| 1 | 156 (19.9%) |

591 (19.7%) |

747 (19.7%) |

||

| 2 | 113 (14.4%) |

506 (16.9%) |

619 (16.4%) |

||

| 3 | 217 (27.6%) |

777 (25.9%) |

994 (26.3%) |

||

| 4 | 175 (22.3%) |

617 (20.6%) |

792 (20.9%) |

||

| Region | East | 206 (26.2%) |

651 (21.7%) |

857 (22.6%) |

0.0003* |

| North Central | 99 (12.6%) |

420 (14.0%) |

519 (13.7%) |

||

| South | 173 (22.0%) |

862 (28.7%) |

1035 (27.3%) |

||

| West | 307 (39.1%) |

1067 (35.6%) |

1374 (36.3%) |

||

| Tumor Primary Site | Left | 307 (39.1%) |

1071 (35.7%) |

1378 (36.4%) |

0.0942 |

| Right | 434 (55.3%) |

1712 (57.1%) |

2146 (56.7%) |

||

| Other/Unknown | 44 (5.6%) |

217 (7.2%) |

261 (6.9%) |

||

| Grade | 1 | 34 (4.3%) |

124 (4.1%) |

158 (4.2%) |

0.788 |

| 2 | 418 (53.2%) |

1554 (51.8%) |

1972 (52.1%) |

||

| 3 | 181 (23.1%) |

694 (23.1%) |

875 (23.1%) |

||

| Other/Unknown | 152 (19.4%) |

628 (20.9%) |

780 (20.6%) |

||

| Teaching Hospital | Yes | 355 (45.2%) |

1184 (39.5%) |

1539 (40.7%) |

0.0078* |

| No | 28 (3.6%) |

145 (4.8%) |

173 (4.6%) |

||

| Unknown | 370 (47.1%) |

1548 (51.6%) |

1918 (50.7%) |

||

| Missing | 155 | ||||

| Metropolitan | Metropolitan | 714 (91.0%) |

2641 (88.0%) |

3355 (88.6%) |

0.0229* |

| Non-metropolitan | 71 (9.0%) |

358 (11.9%) |

429 (11.3%) |

||

| Charlson Comorbidity Score | 0 | 362 (46.1%) |

1568 (52.3%) |

1930 (51.0%) |

0.0107* |

| 1 | 196 (25.0%) |

687 (22.9%) |

883 (23.3%) |

||

| >=2 | 157 (20.0%) |

508 (16.9%) |

665 (17.6%) |

||

| Missing | 307 | ||||

| Received bevacizumab | Yes | 592 (75.4%) |

2279 (76.0%) |

2871 (75.9%) |

0.7474 |

| No | 193 (24.6%) |

721 (24.0%) |

914 (24.1%) |

||

| Total | 785 | 3000 | 3785 |

Abbreviations: SES: Socioeconomic status

Table 2 shows the odds of getting FOLFIRI instead of FOLFOX based on demographic and treatment characteristics. After 2007, the likelihood of a patient taking FOLFIRI over FOLFOX steadily decreased, with an OR of 0.67 (95%CI 0.55 to 0.83) in years 2008–2010, and 0.67 (95%CI 0.54 to 0.82) in years 2011–2013. Similarly, women had a lower likelihood of receiving FOLFIRI over FOLFOX than men (OR, 0.82 (95%CI, 0.69 to 0.98)). On the other hand, patients who had a higher Charlson comorbidity score had a higher likelihood of receiving FOLFIRI (Score of 1: OR, 1.28 (95%CI, 1.02 to 1.53) and Score of 2: OR, 1.33 (95%CI, 1.07 to 1.67)). The southern region also had a significant response as they had a lower probability of receiving FOLFIRI than the eastern region (OR 0.68, 95%CI 0.51 to 0.90).

The multivariate analysis reveals no statistical difference between academic and community hospitals in their prescription of either FOLFOX or FOLFIRI. Race, socioeconomic status, bevacizumab use, and grade were similarly not associated with either treatment regimen.

From the years 2005–2014, the survival of patients who received FOLFOX was comparable to those who received FOLFIRI, with a median overall survival of 19.1 versus 20.5 months (p = 0.37) (Figure 1a). Within cases stratified by tumor site, patients who had a left-sided tumor had a better overall survival than patients with a right-sided tumor (median OS 23.4 versus 18.2 months, respectively; p = 0.001). There was no difference in the survival curves for both right and left-sided tumors when comparing treatment type. Patients with a left-sided tumor treated with FOLFOX had the same overall survival as patients with a left-sided tumor treated with FOLFIRI. The same was true for right-sided tumors (Figure 1b, c).

There was significant variation in survival between the different comorbidity levels (median OS, score 0: 20.6, score 1: 17.3, and score 2: 18.6 months; p = 0.001). However, there was no statistical difference when stratified by both comorbidity score and treatment type. Patients had the same overall survival across either FOLFOX or FOLFIRI at each comorbidity level (Figure 1d–f).

Discussion

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend that patients with metastatic colon cancer who are candidates for intensive systemic therapy initiate FOLFOX, XELOX (capecitabine and oxaliplatin), or FOLFIRI14. The outcomes for these three regimens have been comparable in controlled trials. However, the utilization and patterns of care for each regimen and the factors predictive for the receipt of each regimen in the community are unclear. We sought to evaluate the use of FOLFOX or FOLFIRI as first-line therapy for patients older than 65 year of age with stage IV colon cancer. We found that the majority of patients with stage IV colon cancer received FOLFOX (79.3%) first-line. The significant covariates associated with the use of one regimen over the other were comorbidity score, gender, year of diagnosis, and region. There was no significant difference in overall survival between these two treatment types and this effect was not influenced by the comorbidity score or tumor location.

This finding, that approximately 79% of Medicare patients receive FOLFOX as part of their first-line therapy, is consistent with the findings from the pivotal CALGB 80405 phase III trial. In that trial, in which patients were randomized to bevacizumab or cetuximab in addition to the oncologist’s choice of combination chemotherapy, 73% of the patients were given FOLFOX, while 27% were given FOLFIRI15. The trial included a slightly younger patient population (median age 59) than the current study.

The survival benefits of using either oxaliplatin or irinotecan with 5FU/LV for both older and younger patients have been well documented4,5,16. Our results confirm the similar survival benefits of using either drug regimen for the treatment of stage IV colon cancer among SEER-Medicare patients. Furthermore, patients with right- (versus left-) sided tumors and patients with multiple comorbidities have a worse overall survival16,17, and this was the case for our study as well. Patients with right-sided tumors or with multiple comorbidities also do not benefit from one treatment regimen versus the other (Figures 1b–f).

It is interesting to note that our analysis revealed that patients with multiple comorbidities do have a statistically higher likelihood of receiving FOLFIRI over FOLFOX, despite the lack of survival benefit. This effect is probably due to the different toxicity profiles of each drug. FOLFOX is more likely to cause neuropathy and FOLFIRI is more likely to cause GI toxicities, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, and nausea/vomiting 10,18. Physicians may be hesitant to prescribe oxaliplatin based therapy to patients with comorbidities, like diabetes, who might already have neuropathy.

Our results show the opposite trend for women. In the logistic regression analysis, women were statistically less likely than men to be prescribed FOLFIRI. Studies have shown that women more than men experience nausea and vomiting during cancer therapy, as antiemetic drugs are seemingly less effective19,20. FOLFIRI has been shown to cause more nausea and vomiting than FOLFOX10, which might be the reason physicians prescribe FOLFOX to older female patients instead of FOLFIRI.

We also found that while FOLFOX is more popular among SEER-Medicare patients overall, after 2007 the likelihood of a patient being prescribed FOLFOX increased. This was true for both the 2008 – 2010 and 2011 – 2013 groups. FOLFOX’s overall and increasing popularity in the US might be partially explained by treatment for stage III colon cancer. All studies show the similar survival benefit of taking either FOLFOX or FOLFIRI for metastatic colon cancer; however, for adjuvant stage III colon cancer, two studies from the MOSAIC trial in 2004 and 2009 found that only FOLFOX provided an overall survival benefit as adjuvant therapy21,22. As oxaliplatin-based therapy became the standard of care for stage III cancers, physicians might have become more comfortable giving FOLFOX for both stage III and stage IV colon cancer patients.

However, this way of thinking is not universal as FOLFIRI is favored in both Italy and France9. Cost effectiveness may also play a small role in physician preference. While both treatments provide similar quality-adjusted life-year, FOLFOX does provide a significantly lower cost per life year gained23,24.

We were limited in this study by the use of the SEER-Medicare dataset. As the dataset only had patients aged 65 years and older, we cannot assume the treatment patterns described are generalizable to younger patients. Similarly, individual physician preferences cannot be outright determined with only administrative data. Only general trends in patterns of care are available for analysis in SEER data. Our data also only included patients with an initial diagnosis of stage IV colon cancer and not patients with recurrent disease and can therefore not be generalized to those patients. Furthermore, our analysis was restricted to patients who received infusional 5FU with oxaliplatin or irinotecan (FOLFOX or FOLFIRI). Patients given bolus 5FU or capecitabine were excluded (XELOX, XELIRI, IFL). The total number of patients receiving irinotecan or oxaliplatin based therapy for metastatic colon cancer is therefore higher than our reported results. Since this is a retrospective analysis, there could also have been unmeasured confounders that affected the variables we found to be significant.

Conclusion

We found that, as first-line therapy, FOLFOX is used significantly more frequently than FOLFIRI in the treatment of Medicare patients with stage IV colon cancer. FOLFOX’s fewer adverse side effects, lower cost per life year and its efficacy in stage III colon cancer might influence the physician’s decision to administer FOLFOX preferentially over FOLFIRI. Survival benefit did not differ based on the drug regimen and did not differ when treatment was stratified by comorbidity or tumor location. FOLFOX is increasing in popularity as the years go by, with patients diagnosed in later years more likely to be prescribed FOLFOX. This could be based on physician preference as FOLFOX is the primary treatment for stage III colon cancer.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of SEER-Medicare patients with Stage IV colon cancer comparing overall survival between patients treated with FOLFOX (dashed lines) or FOLFIRI (solid lines) from 2005–2013 stratified by tumor location a) for right sided tumors b) for left sided tumors

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves of SEER-Medicare patients with Stage IV colon cancer comparing overall survival between patients treated with FOLFOX (dashed lines) or FOLFIRI (solid lines) from 2005–2013 stratified by comorbidity a) for a Charlson comorbidity score of 0 b) for a Charlson comorbidity score of 1 c) for a Charlson comorbidity score 2

Clinical Practice Points:

One-fourth of colorectal cancer patients present with metastatic disease and these cases are generally treated initially with systemic chemotherapy. FOLFOX or FOLFIRI represent the chemotherapy backbone for metastatic colon cancer treatment. Both treatments provide similar survival benefits for these patients, but are prescribed at different frequencies across the US. In this study, we found that FOLFOX is used significantly more frequently as first-line therapy than FOLFIRI and is becoming more popular over time. Various demographic and clinical factors were associated with the use of one of the regimens over the other. This study complements existing research describing US oncology practice, and also elucidates new practice patterns associated with systemic chemotherapy usage for metastatic colon cancer.

Acknowledgments:

Dr. Wright (NCI R01CA169121–01A1) and Dr. Hershman (NCI R01 CA166084) are recipients of grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Hershman is the recipient of a grant from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation/Conquer Cancer Foundation..

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest:

Dr. Wright has served as a consultant for Tesaro and Clovis Oncology. Dr. Neugut has served as a consultant to Pfizer, Teva, Eisai, Otsuka, and United Biosource Corporation. He is on the medical advisory board of EHE, Intl. No other authors have any conflicts of interest or disclosures.

References

- 1.Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Lin EH, Crane CH. Stage IV Colorectal Cancer Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine 6th edition. 2003. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK13267/. Accessed July 25, 2018.

- 2.Colorectal Cancer - Cancer Stat Facts. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html. Accessed July 30, 2018.

- 3.Misset JL, Bleiberg H, Sutherland W, Bekradda M, Cvitkovic E. Oxaliplatin clinical activity: a review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2000;35(2):75–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giacchetti S, Perpoint B, Zidani R, et al. Phase III Multicenter Randomized Trial of Oxaliplatin Added to Chronomodulated Fluorouracil–Leucovorin as First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. JCO. 2000;18(1):136-136. 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saltz LB, Cox JV, Blanke C, et al. Irinotecan plus Fluorouracil and Leucovorin for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343(13):905–914. 10.1056/NEJM200009283431302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Morton RF, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Fluorouracil Plus Leucovorin, Irinotecan, and Oxaliplatin Combinations in Patients With Previously Untreated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. JCO. 2004;22(1):23–30. 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gluzman A, Rubinov K, Mermershtain W, Man S, Ariad S, Lavrenkov K. Retrospective comparison of two different schedules of irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid in previously untreated patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma: a single institution experience. J Chemother. 2007;19(6):739–743. 10.1179/joc.2007.19.6.739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abrams TA, Meyer G, Schrag D, Meyerhardt JA, Moloney J, Fuchs CS. Chemotherapy usage patterns in a US-wide cohort of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(2):djt371 10.1093/jnci/djt371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Z, Pelletier E, Barber B, et al. Patterns of treatment with chemotherapy and monoclonal antibodies for metastatic colorectal cancer in Western Europe. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(2):221–229. 10.1185/03007995.2011.650503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tournigand C, André T, Achille E, et al. FOLFIRI Followed by FOLFOX6 or the Reverse Sequence in Advanced Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized GERCOR Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(2):229–237. 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T, et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncology; London. 2014;15(10):1065–1075. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70330-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du XL, Fang S, Meyer TE. Impact of Treatment and Socioeconomic Status on Racial Disparities in Survival Among Older Women With Breast Cancer: American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;31(2):125–132. 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181587890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology Screening Guidelines for the Prevention and Early Detection of Cervical Cancer. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2012;137(4):516–542. 10.1309/AJCPTGD94EVRSJCG [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venook AP, Niedzwiecki D, Lenz H-J, et al. CALGB/SWOG 80405: Phase III trial of irinotecan/5-FU/leucovorin (FOLFIRI) or oxaliplatin/5-FU/leucovorin (mFOLFOX6) with bevacizumab (BV) or cetuximab (CET) for patients (pts) with KRAS wild-type (wt) untreated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum (MCRC). JCO. 2014;32(18_suppl):LBA3–LBA3. 10.1200/jco.2014.32.18_suppl.lba3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vargas GM, Sheffield KM, Parmar AD, et al. Trends in Treatment and Survival in Older Patients Presenting with Stage IV Colorectal Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(2):369–377. 10.1007/s11605-013-2406-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlton ME, Kahl AR, Greenbaum AA, et al. KRAS Testing, Tumor Location, and Survival in Patients With Stage IV Colorectal Cancer: SEER 2010–2013. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(12):1484–1493. 10.6004/jnccn.2017.7011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasetto LM, Jirillo A, Iadicicco G, Rossi E, Paris MK, Monfardini S. FOLFOX Versus FOLFIRI: A Comparison of Regimens in the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer Metastases. Anticancer Res. 2005;25(1B):563–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmetzer O, Flörcken A. Sex Differences in the Drug Therapy for Oncologic Diseases In: Sex and Gender Differences in Pharmacology. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg; 2013:411–442. 10.1007/978-3-642-30726-3_19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato Y, Tatematsu M, Ishikawa K, Okamoto H, Muro K, Noma H. [Induced nausea and vomiting induced by mFOLFOX6 and FOLFIRI with advanced colorectal cancer: a retrospective survey]. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2011;131(11):1661–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.André T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(19):3109–3116. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2343–2351. 10.1056/NEJMoa032709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tumeh JW, Shenoy PJ, Moore SG, Kauh J, Flowers C. A Markov model assessing the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of FOLFOX compared with FOLFIRI for the initial treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32(1):49–55. 10.1097/COC.0b013e31817c6a4d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mullins CD, Hsiao F-Y, Onukwugha E, Pandya NB, Hanna N. Comparative and cost-effectiveness of oxaliplatin-based or irinotecan-based regimens compared with 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin alone among US elderly stage IV colon cancer patients. Cancer. 2012;118(12):3173–3181. 10.1002/cncr.26613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]