Abstract

Short and long sleep duration and poor sleep quality may affect serum and hepatic lipid content, but available evidence is inconsistent. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the associations of sleep duration and quality with serum and hepatic lipid content in a large population‐based cohort of middle‐aged individuals. The present cross‐sectional study was embedded in the Netherlands Epidemiology of Obesity (NEO) study and consisted of 4260 participants (mean age, 55 years; proportion men, 46%) not using lipid‐lowering agents. Self‐reported sleep duration and quality were assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index questionnaire (PSQI). Outcomes of this study were fasting lipid profile (total cholesterol, low‐density lipoprotein [LDL]‐cholesterol, high‐density lipoprotein [HDL]‐cholesterol and triglycerides), postprandial triglyceride (response) levels, and hepatic triglyceride content (HTGC) as measured with magnetic resonance spectroscopy. We performed multivariable linear regression analyses, adjusted for confounders and additionally for measures that link to adiposity (e.g. body mass index [BMI] and sleep apnea). We observed that relative to the group with median sleep duration (≈7.0 hr of sleep), the group with shortest sleep (≈5.0 hr of sleep) had 1.5‐fold higher HTGC (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.0‐2.2). The group with PSQI score ≥ 10 had a 1.1‐fold (95% CI: 1.0‐1.2) higher serum triglyceride level compared with the group with PSQI ≤ 5. However, these associations disappeared after adjustment for BMI and sleep apnea. Therefore, we concluded that previously observed associations of shorter sleep duration and poorer sleep quality with an adverse lipid profile, may be explained by BMI and sleep apnea, rather than by a direct effect of sleep on the lipid profile.

Keywords: cardiovascular diseases, lifestyle, lipids, obesity, sleep

1. INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the leading causes of death worldwide and was responsible for 17.7 million deaths in 2015 (WHO 2017). Several lifestyle factors have been associated with a deleterious CVD risk profile and a higher risk of cardiovascular mortality, for example smoking and alcohol intake (Jha et al., 2013). Multiple epidemiological studies have shown that sleep duration is another important risk factor for the development of CVD (Aggarwal, Loomba, Arora, & Molnar, 2013; Cappuccio et al., 2008; Cappuccio, Cooper, & D'elia, L., Strazzullo, P. and Miller, M. A., 2011; Ford, 2014; Lee & Park, 2014; Petrov et al., 2013; van den Berg et al., 2008; Wu, Zhai, & Zhang, 2014; Xi, He, Zhang, Xue, & Zhou, 2014). However, in some studies both extremes (long and short sleep duration) are associated with an increased risk of CVD (Aggarwal et al., 2013; Ford, 2014), whereas in other studies only short sleep duration or long sleep duration has been associated with an increased risk of CVD and with CVD risk factors (notably obesity and metabolic syndrome) (Cappuccio et al., 2011, 2008 ; Lee & Park, 2014; Petrov et al., 2013; Shin et al., 2016; van den Berg et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2014; Xi et al., 2014; Zhan, Chen, & Yu, 2014).

Besides sleep duration, poor sleep quality has been associated with an increased risk of metabolic syndrome (Koren, Dumin, & Gozal, 2016; Mesas et al., 2014), yet not in all studies (Petrov et al., 2013). Several factors could contribute to the discrepant findings regarding the associations of sleep duration and sleep quality with cardiovascular risk factors. Body mass index (BMI) and sleep apnea are associated with alterations in sleep and with high circulating lipids and incidence of coronary heart disease (Dale, Fatemifar, & Palmer, 2017; Javaheri, Barbe, & Campos‐Rodriguez, 2017). In the study by Petrov et al. (2013) poor sleep quality was associated with a poor lipid profile; however, after adjustment for covariates, including BMI and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) risk, this association disappeared (Petrov et al., 2013). Importantly, although previous studies generally adjusted for BMI, most studies did not adjust for sleep apnea (Cappuccio et al., 2011, 2008 ; Lee & Park, 2014; Petrov et al., 2013; Shin et al., 2016; van den Berg et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2014; Xi et al., 2014; Zhan et al., 2014). Therefore, the question remains to what extent the previously described associations of sleep duration and sleep quality with CVD were confounded by BMI and OSA. Moreover, both BMI and OSA are risk factors for non‐alcoholic liver disease (NAFLD) (Bray, 2004; Mirrakhimov & Polotsky, 2012; Sundaram et al., 2014), which is a risk factor for myocardial dysfunction (Widya et al., 2016). To the best of our knowledge, hepatic triglyceride content (HTGC) has not been studied in relation to sleep duration and/or sleep quality.

Based on previous studies, we hypothesized that both short and long sleep duration and poor sleep quality are associated with an adverse serum and hepatic lipid profile. However, we hypothesize that after adjustment for BMI and the risk of sleep apnea, these associations may decrease. In the present study, we aim to assess these associations in a large population‐based cohort of middle‐aged adults from the Netherlands, considering all important confounding factors (including BMI and sleep apnea).

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and study population

The present study is a cross‐sectional analysis of baseline measurements of the Netherlands Epidemiology of Obesity (NEO) study, a cohort of 6671 individuals, with an oversampling of individuals with overweight or obesity. Between September 2008 and September 2012, men and women aged between 45 and 65 years with a self‐reported BMI of 27 kg/m2 or higher living in the greater area of Leiden were invited to participate in the NEO study. In addition, all inhabitants aged between 45 and 65 years from one municipality (Leiderdorp) were invited irrespective of their BMI, allowing for a reference distribution of BMI. Baseline data were collected at the NEO study centre of the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC). Prior to the NEO study visit, participants completed a questionnaire about demographic and clinical information and fasted for at least 10 hr. Participants came to the research site in the morning to undergo several baseline measurements, including anthropometric measurements and fasting and postprandial blood sampling. At the study site, a screening form was completed by all participants, asking about anything that might create a health risk or interfere with MRI imaging (most notably metallic devices, claustrophobia and a body circumference of more than 1.70 m). Of the participants who were eligible for MRI, approximately 35% of the total study population were randomly selected to undergo direct assessment of VAT. A medication inventory was performed to collect data on medication use during the month preceding the visit to the study centre. More detailed information on the study design and data collection has been given elsewhere (de Mutsert et al., 2013).

This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the LUMC (and the NEO board) and all participants gave written informed consent. In the present study, we excluded participants with missing data on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PQSI) questionnaire (n = 1402). The PSQI questionnaire was only added to the baseline questionnaire after July 2009 and therefore participants entering the study before this date have missing data on this questionnaire. Moreover, we excluded participants who used lipid‐lowering drugs (n = 791), had missing baseline characteristics (n = 118), had missing data from the Berlin questionnaire (n = 53), were not in a fasting state during the hospital visit (n = 19), or had missing data on serum triglycerides (n = 27) or cholesterol (n = 1). We additionally excluded participants who drank >40 g alcohol per day (n = 344) from the analyses of HTGC. For the analyses on postprandial triglyceride levels, we excluded participants with missing or incomplete postprandial serum triglyceride concentrations (n = 221) or who had no or incomplete liquid meal intake (n = 2) (Figure S1).

2.2. Sleep characteristics

To assess habitual sleep duration and quality, we used the PSQI (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989), which is a self‐rated questionnaire to retrospectively measure sleep parameters over a 1‐month time interval. Total sleep duration was derived from the question: On an average day, how much sleep do you get? To obtain a classification of short and long total sleep duration, we calculated the age‐ and sex‐adjusted residuals with linear regression analysis for total sleep duration with age and sex and determined subgroups on the basis of these residuals. We used the 5th lowest percentile of the age‐ and sex‐adjusted residuals to define shortest sleep, the 5th to 20th percentile to define short sleep, the 20th to 80th to define medium sleep, the 80th to 95th to define long sleep, and the 95th to 100th percentile to define longest sleep. Sleep quality was assessed using the total score of the PSQI questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of seven components, from which an overall score can be calculated. The global score ranges from 0 to 21; a higher score indicates a poorer sleep quality (Buysse et al., 1989). For sleep quality, we formed three sleep‐quality groups, and we used the good sleep quality group (PSQI total score ≤5) as a reference group in linear regression analyses. The poor sleep quality group was defined by a PSQI total score between 5 and 10, and worst sleep quality defined as PSQI total score ≥10.

2.3. Serum lipid profile and hepatic triglyceride content

After an overnight fast of at least 10 hr, fasting blood samples were taken at the study centre. Within 5 min after the first blood sample was taken, participants drank a liquid mixed meal (400 ml) with an energy content of 600 kcal, with 16% of energy derived (En%) from protein, 50 En% from carbohydrates and 34 En% from fat. Postprandial blood samples were taken 30 and 150 min after ingestion of the meal. Serum triglyceride concentrations were determined at the three time‐points. Serum total cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations were determined by enzymatic colorimetric methods (Roche Modular Analytics P800, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany; CV < 5%) and high‐density lipoprotein (HDL)‐cholesterol with the homogenous HDLc method (third generation) (Roche Modular Analytics P800, Roche Diagnostics; CV < 5%). Low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol concentration was estimated using Friedewald's formula (Friedewald, Levy, & Fredrickson, 1972). All measures were performed in the central clinical chemistry laboratory of the LUMC. The area under the curve (AUC) for postprandial serum triglyceride levels was calculated using the trapezoid rule as (15 * fasting concentration + 75 * concentration30min + 60 * concentration150min)/150 (Retnakaran et al., 2008).

Hepatic 1H magnetic resonance (MR) spectra were obtained in a random subset of 1207 participants with data on habitual sleep. In short, an 8‐mL voxel was positioned in the right lobe of the liver. A point‐resolved spectroscopy sequence was used to acquire spectroscopic data during continuous breathing with automated shimming. Spectra were obtained with and without water suppression. Spectral data were fitted by using Java‐based MR user interface software (jMRUI, version 3.0; developed by A. van den Boogaart, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium) (Naressi et al., 2001). Mean line widths of the spectra were calculated. The resonances that were fitted and used for calculation of the triglycerides were methylene (peak at 1.3 ppm, [CH2]n) and methyl (peak at 0.9 ppm, CH3). The HTGC relative to water was calculated with the following formula: (signal amplitude of methylene + methyl)/(signal amplitude of water) × 100.

2.4. Covariates

A semi‐quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) (Feunekes, Staveren, Vries, Burema, & Hautvast, 1993) was used to assess energy intake. Energy intake was estimated from the FFQ with the 2011 version of the Dutch food composition table (NEVO‐2011). Participants reported the frequency and duration of their physical activity in leisure time using the Short Questionnaire to Assess Health‐enhancing Physical Activity (SQUASH) (Wendel‐Vos, Schuit, Saris, & Kromhout, 2003), which was expressed in hours per week of metabolic equivalents (MET‐hr/week). Body weight was measured at the study centre without shoes and 1 kg was subtracted to correct for the weight of clothing. BMI was calculated by dividing the weight in kilograms by the height in metres squared. The risk for the presence of OSA syndrome was assessed using the Berlin questionnaire (Netzer, Stoohs, Netzer, Clark, & Strohl, 1999). This questionnaire consists of 10 questions that form three categories (snoring [category 1], daytime somnolence [category 2] and hypertension and BMI [category 3]) related to the likelihood of the presence of sleep apnea. Individuals can be classified as either having a high (two or more categories with a positive score) or low likelihood of sleep apnea (only one or no categories with a positive score).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Because individuals with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or higher were oversampled in the NEO study population, adjustments were made to correctly represent associations in the general population (Korn & Graubard, 1991; Ministerie van VWS). This was done by weighting individuals towards the BMI distribution of participants from the Leiderdorp municipality, whose BMI distribution was similar to the BMI distribution of the general Dutch population (de Mutsert et al., 2013). Consequently, all presented results are based on weighted analyses and apply to a population‐based study without oversampling of participants with a BMI of 27 kg/m2 or higher. Characteristics of the study population were expressed as mean (with standard deviation, SD) for normally distributed measures, median with interquartile ranges for non‐normally distributed measures, and proportions for categorical variables. We performed all statistical analyses using Stata version 12.1 software (Stata, College Station, Texas, USA).

Non‐normally distributed outcomes were log transformed to approximate a normal distribution (notably serum triglycerides, HTGC, and AUC of serum triglycerides). However, in order to present the results with a similar interpretation, we log transformed normally distributed outcomes (notably serum HDL‐cholesterol, LDL‐cholesterol and total cholesterol) as well. We performed linear regression analyses using the medium sleep category (characterized by the 20th to 80th percentile of sleep duration residuals) as the reference group. The subsequent beta regression coefficients were back transformed and expressed as a ratio with accompanying 95% confidence interval (95% CI), which can be interpreted as the relative change in outcome compared with the reference group. The initial model for linear regression analyses was adjusted for age and sex (Model 1). In addition to age and sex, in Model 2 we adjusted for ethnicity (white/other), education level (high/other), smoking (never/former/current), alcohol consumption, energy intake, physical activity and sleep medication (yes/no). In Model 3 we additionally adjusted for BMI and sleep apnea. In the analyses for sleep quality we did not adjust for sleep medication in Models 2 and 3, as this is a component of the PSQI total score.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of the study population

In total, after exclusion of non‐eligible participants, this study comprised 4260 participants with a mean age of 55 (SD 6.0) years, of whom 46% were men. As compared with the medium sleep group (40%), there were more men in both the shortest (45%) and the longest (51%) sleep groups (Table 1). Fewer individuals had higher education in both the shortest sleep group (39%) and the longest sleep group (36%) compared with the medium sleep group (51%). More participants used sleep medication in the shortest (14%) and longest sleep groups (7%) as compared with the medium sleep group (4%). HTGC was higher in both the shortest sleep group (6% [25th‐75th percentile: 3‐11%]) and the longest sleep group (4% [2‐8%]) than in the medium sleep group (2% [1‐5%]). All other studied characteristics were similar between the groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in the Netherlands Epidemiology of Obesity study, stratified by sleep duration (n = 4260)

| Sleep duration | Shortest | Short | Medium | Long | Longest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0%–5% | 5%–20% | 20%–80% | 80%–95% | 95%–100% | |

| Age (years) | 57 (5) | 57 (5) | 55 (6) | 54 (6) | 57 (6) |

| Sex (% men) | 45 | 47 | 40 | 41 | 51 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27 (5) | 26 (5) | 26 (4) | 26 (4) | 26 (5) |

| Ethnicity (% white) | 90 | 93 | 96 | 96 | 93 |

| Education (% high) | 39 | 43 | 51 | 48 | 36 |

| Smoking (% current) | 19 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 19 |

| Sleep medication (%) | 14 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| Alcohol consumption (g/day) | 12 (3‐22) | 10 (3‐22) | 10 (3‐21) | 9 (2‐21) | 9 (0‐21) |

| Physical activity (MET‐hr/week) | 25 (12‐44) | 30 (16‐47) | 30 (17‐50) | 32 (16‐52) | 30 (15‐51) |

| Sleep duration (hr/day) | 5 (4‐5) | 6 (6‐6) | 7 (7‐8) | 8 (8‐8) | 9 (9‐9) |

| PSQI (total score) | 11 (9‐13) | 7 (5‐10) | 4 (3‐6) | 3 (2‐4) | 3 (2‐5) |

| Sleep apnea (%) | 33 | 26 | 16 | 16 | 22 |

| Fasting total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 6 (1) | 6 (1) | 6 (1) | 6 (1) | 6 (1) |

| Fasting LDL‐cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Fasting HDL‐cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (0) | 2 (0) |

| Fasting triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1 (1‐2) | 1 (1‐2) | 1 (1‐1) | 1 (1‐2) | 1 (1‐1) |

| Triglycerides 30 min (mmol/L) | 1 (1‐2) | 1 (1‐2) | 1 (1‐2) | 1 (1‐2) | 1 (1‐2) |

| Triglycerides 120 min (mmol/L) | 2 (1‐3) | 2 (1‐2) | 2 (1‐2) | 2 (1‐2) | 2 (1‐2) |

| AUC triglyceridesa | 48 (28‐77) | 48 (26‐73) | 46 (26‐66) | 46 (27‐68) | 44 (26‐68) |

| Hepatic triglyceride content (%)b | 6 (3‐11) | 3 (2‐6) | 2 (1‐5) | 2 (1‐6) | 4 (2‐8) |

AUC, area under the curve; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; kJ, kilojoule; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; MET, metabolic equivalents of task; NEO, Netherlands Epidemiology of Obesity; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Questionnaire Index. Results were based on analyses weighted towards the BMI distribution of the general Dutch population. Data presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD); proportion (%); median (25th−75th percentile).

n = 4037.

n = 1272.

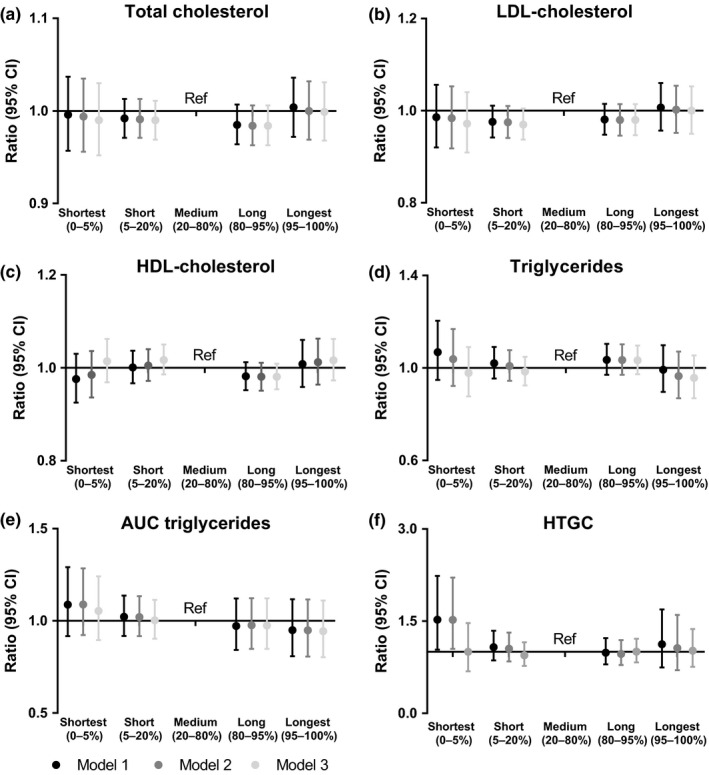

3.2. Associations between sleep duration and fasted and postprandial lipids

In the analyses adjusted for age and sex (Model 1), shortest sleep duration was associated with a 1.52‐fold (95% CI: 1.04‐2.24) higher HTGC as compared with the medium sleep group (Figure 1 and Table S1). This association persisted after adjustment for potential confounding factors (Model 2). However, the association between shortest sleep and higher HTGC disappeared after we additionally adjusted for BMI and sleep apnea in Model 3 (ratio of 1.00; 95% CI: 0.68–1.45). There were no associations between short and long sleep duration and total cholesterol, LDL‐cholesterol, HDL‐cholesterol, triglycerides, or AUC of triglycerides.

Figure 1.

Associations between sleep duration and (a) TC, (b) LDL‐cholesterol, (c) HDL‐cholesterol, (d) TG, (e) AUC of TG and (f) hepatic triglyceride content (HTGC). The medium sleep duration group is used as a reference category in linear regression analyses. Results are presented as ratios with accompanying 95% CIs, linear regression coefficients of the log transformed outcomes were back transformed in order to present ratios. The ratio reflects the relative change to provide an indication of the fold change of the outcome as compared with the reference category. Results were based on analyses weighted towards the BMI distribution of the general Dutch population. Model 1, adjusted for age and sex; Model 2, adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, education level, smoking, alcohol intake, caloric intake and physical activity; Model 3, adjusted for Model 2 + sleep apnea and BMI. AUC, area under the curve; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HTGC, hepatic triglyceride content; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; Ref, reference category; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride

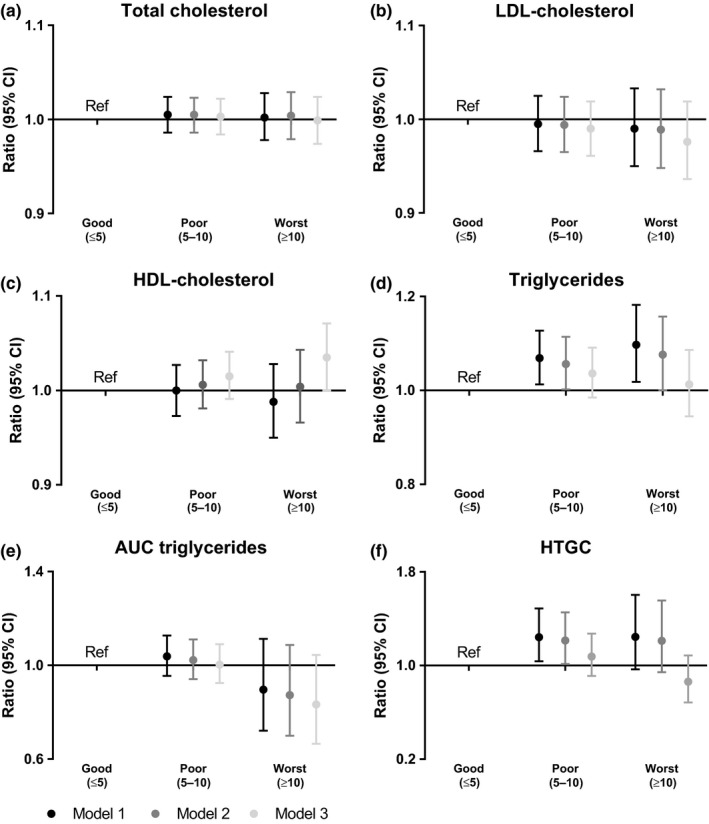

3.3. Associations between sleep quality and fasting and postprandial lipids

A poor sleep quality (PSQI total score 5–10; Figure 2 and Table S2) was associated with a 1.07‐fold (95% CI: 1.01‐ 1.13) increased serum triglyceride level in the analyses (age and sex adjusted) as compared with good sleep quality (PSQI score ≤ 5). Adjustment for potential confounding factors (Model 2) did not materially change the results (ratio 1.06 [95% CI, 1.00, 1.11]), but when we additionally adjusted for BMI and sleep apnea (Model 3), the association between poor sleep quality and serum triglycerides disappeared (ratio 1.04 [95% CI, 0.99, 1.09]). Poor sleep quality was associated with a 1.24‐fold (95% CI, 1.04, 1.49) increased HTGC as compared with good sleep quality in Model 1, which persisted in Model 2 (ratio 1.21 [95% CI, 1.01, 1.45]). However, after additional adjustment for BMI and sleep apnea (Model 3) the association disappeared (ratio 1.08 [95% CI, 0.91, 1.27]). Worst sleep quality (PSQI ≥ 10) was associated with a 1.10‐fold (95% CI, 1.02, 1.18) increased fasting serum triglyceride level as compared with good sleep quality in Model 1. This association persisted in Model 2 (ratio 1.08 [95% CI, 1.00, 1.16]), but the association disappeared in Model 3 (ratio 1.01 [95% CI 0.9, 1.09]). The correlations between blood and hepatic triglyceride levels, for men and women separately, are displayed in Figure S2. There were no associations between sleep quality and total cholesterol, LDL‐cholesterol, HDL‐cholesterol, or AUC of triglycerides.

Figure 2.

Associations between sleep quality and (a) TC, (b) LDL‐cholesterol, (c) HDL‐cholesterol, (d) TG, (e) AUC of TG and (f) HTGC. The good sleep quality group is used as a reference category in linear regression analyses. Results are presented as ratios with accompanying 95% CI; linear regression coefficients of the log transformed outcomes were back transformed in order to present ratios. The ratio reflects the relative change to provide an indication of the fold change of the outcome as compared with the reference category. Results were based on analyses weighted towards the BMI distribution of the general Dutch population. Model 1, adjusted for age and sex; Model 2, adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, education level, smoking, alcohol intake, caloric intake and physical activity; Model 3, adjusted for Model 2 + sleep apnea and BMI. AUC, area under the curve; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HTGC, hepatic triglyceride content; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; Ref, reference category; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride

4. DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to address the associations of sleep duration and quality with HTGC and serum lipid levels in a cohort of 4260 middle‐aged individuals. When analyses were adjusted for age and sex, we observed an association between shortest sleep duration and higher HTGC. Moreover, poor sleep quality was associated with higher fasting serum triglyceride levels and higher HTGC than good sleep quality. However, all observed associations disappeared after additional adjustment for BMI and sleep apnea.

In previous research, it has been shown that both short and long sleep duration, or only short or long sleep duration, were associated with cardiovascular risk and cardiovascular risk factors (Aggarwal et al., 2013; Cappuccio et al., 2011, 2008; Ford, 2014; Lee & Park, 2014; Petrov et al., 2013; van den Berg et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2014; Xi et al., 2014). We hypothesized that these discrepant findings could be explained by differences in the considered confounding factors, which includes the adjustment for the confounding factors, BMI and sleep apnea (Dale et al., 2017; Javaheri et al., 2017). In agreement, in our study, when adjusted for age and sex, short sleep duration was associated with higher serum triglyceride levels. When we additionally adjusted for ethnicity, education level, smoking, alcohol intake, caloric intake and physical activity, this association remained. However, this association disappeared after additional adjustment for BMI and sleep apnea. Similarly, we observed an association between poor sleep quality and higher serum triglyceride levels and HTGC after adjustment for classical confounders; however, again these associations disappeared after additional adjustment for BMI and sleep apnea. In agreement, in a cohort study comprising 503 adults, it has been observed that there was no association between poor sleep quality and lipid profile after adjustment for covariates, including BMI and sleep apnea risk (Petrov et al., 2013).

In contrast to our findings, a study by Anujuo (2015) did not observe an association between short sleep duration and higher triglyceride levels in either of their analyses (adjusted for only age and sex or other confounding factors including BMI) in a population consisting of 2146 participants of Dutch origin. One of the explanations for these discrepant findings could be the different cut‐off point used for determining short sleep duration, which was <7 hr based on the small number of individuals with very short sleep duration. Therefore, the group defined as ‘short sleep’ might not have sufficiently short sleep to observe clinically relevant associations with lipid levels.

Questions regarding the direction of the observed associations remain to be elucidated. In this study, we considered BMI and sleep apnea as potential confounding factors, suggesting that BMI and sleep apnea are common causes of alterations in sleep and in lipid metabolism. Alternatively, sleep duration might have a causal effect on BMI and sleep apnea, meaning that BMI and sleep apnea may mediate the association between sleep and cardiovascular risk factors. In this case the observed associations between sleep duration/quality and serum and hepatic lipid profiles in the present study may be underestimated.

There are several biological pathways that could link sleep duration and quality to CVD. For example, a short sleep duration might have an adverse effect on cardiovascular health via increased cortisol levels and/or inflammatory mediators through higher sympathetic nervous system activity (Lucassen, Rother, & Cizza, 2012). In addition, a genome‐wide association study on total sleep duration suggests that there is also a shared genetic component between insomnia symptoms and a higher BMI, waist circumference and insulin resistance, which have all been associated with a higher risk of developing CVD (Lane et al., 2017). Moreover, a shorter sleep duration has been associated with altered levels of leptin and ghrelin and a higher craving for carbohydrate‐rich foods (Spiegel, Tasali, Penev, & Cauter, 2004; Taheri, Lin, Austin, Young, & Mignot, 2004). These are possible mechanisms via which alteration in sleep could lead to obesity and obesity‐related disorders. Both obesity and sleep apnea are shown to be associated with high circulating lipids and a higher incidence of coronary heart disease (Dale et al., 2017; Javaheri et al., 2017). Moreover, obesity is a risk factor for NAFLD (Bray, 2004). It was shown that a higher HTGC was associated with a higher risk of myocardial dysfunction, as characterized by a lower diastolic function in the NEO study population; however, this was only in obese individuals (Widya et al., 2016). Also, it was shown that OSA is prevalent in 60% of NAFLD patients, and that OSA may contribute to progression of NAFLD (Mirrakhimov & Polotsky, 2012; Sundaram et al., 2014). OSA is thought to exert an effect via different mechanisms (e.g. inflammation, oxidative stress and intermittent hypoxia) (Javaheri et al., 2017) and can be treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) (Gottlieb, Punjabi, & Mehra, 2014). This supports our hypothesis that sleep apnea and BMI affect the relation between short sleep duration and poor sleep quality and CVD. Our findings support the idea of weight loss and sleep apnea screening in individuals with short sleep duration and poor sleep quality in order to contribute to prevention of onset of CVD. Nevertheless, the individual contributions of sleep, sleep quality, circadian rhythm and other lifestyle adaptations, and their interrelations, are complex and difficult to assess separately and at least require prospective analyses in large populations.

A strength of this study is the use of residuals as a determinant for sleep duration. By using the residuals, we obtained a classification of sleep duration that is independent of age and sex. One of the other strengths of this study is the extensive phenotyping of the NEO study, which enables us to correct for a broad range of possible confounding factors (e.g. ethnicity, physical activity and risk of sleep apnea). Moreover, previous studies used different questionnaires to assess sleep duration and sleep quality, which may result in inconclusive results. Therefore, we have used the PSQI questionnaire, which is a widely used and validated tool, to assess sleep disturbances (Mollayeva et al., 2016). However, the present study also has some limitations. First, inherent to the observational cross‐sectional design, we are not able to exclude reverse causation or residual confounding in this study. Second, we used subjective sleep questionnaires to assess sleep duration and sleep quality and the risk of sleep apnea. Self‐reported data are subject to recall bias, whereby participants may either under‐ or over‐report their sleep duration and their quality of sleep. There may be a measurement error that results in non‐differential misclassification of the exposure. However, the PSQI was shown to be a reliable and validated tool to assess sleep dysfunction (Mollayeva et al., 2016). Moreover, although the risk of sleep apnea is self‐reported using the Berlin questionnaire, this tool has also been validated in several populations and showed the highest specificity to detect mild and severe OSA in patients from sleep clinics, as compared with other OSA screening questionnaires (Amra, Rahmati, Soltaninejad, & Feizi, 2018).

In conclusion, we observed that shorter sleep duration and poorer sleep quality were associated with an adverse lipid profile. However, all observed associations disappeared after additional adjustment for BMI and sleep apnea, indicating that BMI and risk of sleep apnea probably confound previously observed associations and should therefore be considered in future studies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design: MMB, RN, RvdB, NRB and DvH. Data‐analysis: MMB and RN. Interpretation of the data: MMB, RN, GJB, PCNR, NRB and DvH. Acquisition of data: RdM, FRR and NRB. Drafting the manuscript: MMB. Commenting on the initial versions of the manuscript and final approval: MMB, RN, RvdB, RdM, FRR, GJB, PCNR, NRB and DvH.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We express our gratitude to all individuals who participated in the NEO study, in addition to all participating general practitioners. We furthermore thank P.R. van Beelen and all research nurses for collecting the data, P.J. Noordijk and her team for sample handling and storage, and I. de Jonge for data management of the NEO study. The NEO study is supported by the participating departments, the Division and the Board of Directors of the Leiden University Medical Centre, and by the Leiden University Research Profile Area ‘Vascular and Regenerative Medicine’. Nutricia Research, Utrecht, the Netherlands, provided the mixed meal. We acknowledge the support from the Netherlands Cardiovascular Research Initiative: an initiative with support of the Dutch Heart Foundation (CVON2014‐02 ENERGISE). DvH was supported by the European Commission‐funded project HUMAN (Health‐2013‐INNOVATION‐1‐602757). NB was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO‐VENI 016.136.125).

Bos MM, Noordam R, van den Berg R, et al. Associations of sleep duration and quality with serum and hepatic lipids: The Netherlands Epidemiology of Obesity Study. J Sleep Res. 2019;28:e12776 10.1111/jsr.12776

REFERENCES

- Aggarwal, S. , Loomba, R. S. , Arora, R. R. , & Molnar, J. (2013). Associations between sleep duration and prevalence of cardiovascular events. Clinical Cardiology, 36, 671–676. 10.1002/clc.22160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amra, B. , Rahmati, B. , Soltaninejad, F. , & Feizi, A. (2018). Screening questionnaires for obstructive sleep apnea: An updated systematic review. Oman Medical Journal, 33, 184–192. 10.5001/omj.2018.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anujuo, K. , Stronks, K. , Snijder, M. B. , Jean‐Louis, G. , Rutters, F. , … Agyemang, C. (2015). Relationship between short sleep duration and cardiovascular risk factors in a multi‐ethnic cohort – the helius study. Sleep Medicine, 16, 1482–1488. 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray, G. A. (2004). Medical consequences of obesity. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 89, 2583–2589. 10.1210/jc.2004-0535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse, D. J. , Reynolds, C. F. 3rd , Monk, T. H. , Berman, S. R. , & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28, 193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio, F. P. , Cooper, D. , D'Elia, L. , Strazzullo, P. , & Miller, M. A. (2011). Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of prospective studies. European Heart Journal, 32, 1484–1492. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio, F. P. , Taggart, F. M. , Kandala, N. B. , Currie, A. , Peile, E. , Stranges, S. , & Miller, M. A. (2008). Meta‐analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep, 31, 619–626. 10.1093/sleep/31.5.619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale, C. E. , Fatemifar, G. , Palmer, T. M. , White, J. , Prieto-Merino, D. , Zabaneh, D. , … Casas, J. P. (2017). Causal associations of adiposity and body fat distribution with coronary heart disease, stroke subtypes, and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A Mendelian randomization analysis. Circulation, 135, 2373–2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mutsert, R. , Den Heijer, M. , Rabelink, T. J. , Smit, J. W. A. , Romijn, J. A. , Jukema, J. W. , … Rosendaal, F. R. (2013). The Netherlands Epidemiology of Obesity (NEO) study: Study design and data collection. European Journal of Epidemiology, 28, 513–523. 10.1007/s10654-013-9801-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feunekes, G. I. , Van Staveren, W. A. , De Vries, J. H. , Burema, J. , & Hautvast, J. G. (1993). Relative and biomarker‐based validity of a food‐frequency questionnaire estimating intake of fats and cholesterol. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 58, 489–496. 10.1093/ajcn/58.4.489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford, E. S. (2014). Habitual sleep duration and predicted 10‐year cardiovascular risk using the pooled cohort risk equations among US adults. Journal of the American Heart Association, 3, e001454 10.1161/JAHA.114.001454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald, W. T. , Levy, R. I. , & Fredrickson, D. S. (1972). Estimation of the concentration of low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clinical Chemistry, 18, 499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, D. J. , Punjabi, N. M. , Mehra, R. , Patel, S. R. , Quan, S. F. , Babineau, D. C. , … Redline, S. (2014). CPAP versus oxygen in obstructive sleep apnea. New England Journal of Medicine, 370, 2276–2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javaheri, S. , Barbe, F. , Campos‐Rodriguez, F. , Dempsey, J. A. , Khayat, R. , Javaheri, S. , … Somers, V. K. (2017). Sleep Apnea: Types, Mechanisms, and Clinical Cardiovascular Consequences. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 69, 841–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha, P. , Ramasundarahettige, C. , Landsman, V. , Rostron, B. , Thun, M. , Anderson, R. N. , … Peto, R. (2013). 21st‐century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 368, 341–350. 10.1056/nejmsa1211128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren, D. , Dumin, M. , & Gozal, D. (2016). Role of sleep quality in the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity, 9, 281–310. 10.2147/dmso.s95120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn, E. L. , & Graubard, B. I. (1991). Epidemiologic studies utilizing surveys: Accounting for the sampling design. American Journal of Public Health, 81, 1166–1173. 10.2105/AJPH.81.9.1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane, J. M. , Liang, J. , Vlasac, I. , Anderson, S. G. , Bechtold, D. A. , Bowden, J. , … Saxena, R. (2017). Genome‐wide association analyses of sleep disturbance traits identify new loci and highlight shared genetics with neuropsychiatric and metabolic traits. NatureGenetics, 49, 274–281. 10.1038/ng.3749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. A. , & Park, H. S. (2014). Relation between sleep duration, overweight, and metabolic syndrome in Korean adolescents. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases, 24, 65–71. 10.1016/j.numecd.2013.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucassen, E. A. , Rother, K. I. , & Cizza, G. (2012). Interacting epidemics? Sleep curtailment, insulin resistance, and obesity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1264, 110–134. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06655.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesas, A. E. , Guallar‐Castillon, P. , Lopez‐Garcia, E. , León‐Muñoz, L. M. , Graciani, A. , Banegas, J. R. , & Rodríguez‐Artalejo, F. (2014). Sleep quality and the metabolic syndrome: The role of sleep duration and lifestyle. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews, 30, 222–231. 10.1002/dmrr.2480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirrakhimov, A. E. , & Polotsky, V. Y. (2012). Obstructive sleep apnea and non‐alcoholic Fatty liver disease: Is the liver another target? Frontiers in Neurology, 3, 149 10.3389/fneur.2012.00149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollayeva, T. , Thurairajah, P. , Burton, K. , Mollayeva, S. , Shapiro, C. M. , & Colantonio, A. (2016). The Pittsburgh sleep quality index as a screening tool for sleep dysfunction in clinical and non‐clinical samples: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 25, 52–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naressi, A. , Couturier, C. , Devos, J. M. , Janssen, M. , Mangeat, C. , de Beer, R. , & Graveron‐Demilly, D. (2001). Java‐based graphical user interface for the MRUI quantitation package. Magma: Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology, and Medicine, 12, 141–152. 10.1007/BF02668096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netzer, N. C. , Stoohs, R. A. , Netzer, C. M. , Clark, K. , & Strohl, K. P. (1999). Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Annals of Internal Medicine, 131, 485–491. 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov, M. E. , Kim, Y. , Lauderdale, D. , Lewis, C. E. , Reis, J. P. , Carnethon, M. R. , … Glasser, S. J. (2013). Longitudinal associations between objective sleep and lipids: The CARDIA study. Sleep, 36, 1587–1595. 10.5665/sleep.3104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retnakaran, R. , Shen, S. , Hanley, A. J. , Vuksan, V. , Hamilton, J. K. , & Zinman, B. (2008). Hyperbolic relationship between insulin secretion and sensitivity on oral glucose tolerance test. Obesity (Silver Spring), 16, 1901–1907. 10.1038/oby.2008.307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H. Y. , Kang, G. , Kim, S. W. , Kim, J. M. , Yoon, J. S. , & Shin, I. S. (2016). Associations between sleep duration and abnormal serum lipid levels: Data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Sleep Medicine, 24, 119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel, K. , Tasali, E. , Penev, P. , & Van Cauter, E. (2004). Brief communication: Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Annals of Internal Medicine, 141, 846–850. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram, S. S. , Sokol, R. J. , Capocelli, K. E. , Pan, Z. , Sullivan, J. S. , Robbins, K. , & Halbower, A. C. (2014). Obstructive sleep apnea and hypoxemia are associated with advanced liver histology in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Pediatrics, 164(699–706), e1 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taheri, S. , Lin, L. , Austin, D. , Young, T. , & Mignot, E. (2004). Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med, 1, e62 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Berg, J. F. , Miedema, H. M. , Tulen, J. H. M. , Neven, A. K., Hofman, … H. (2008). Long sleep duration is associated with serum cholesterol in the elderly: The Rotterdam Study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 70, 1005–1011. 10.1097/psy.0b013e318186e656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministerie van VWS (Volksgezondheid Welzijn en Sport) . Hoeveel mensen hebben overgewict (Available at: https://www.volksgezondheidenzorg.info/onderwerp/overgewicht/cijfers-context/huidige-situatie, last assessed 20/09/2018).

- Wendel‐Vos, G. C. , Schuit, A. J. , Saris, W. H. , & Kromhout, D. (2003). Reproducibility and relative validity of the short questionnaire to assess health‐enhancing physical activity. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 56, 1163–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2017). Fact sheet Cardiovascular Diseases, Available at: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (last assessed 20/09/2018)

- Widya, R. L. , De Mutsert, R. , Den Heijer, M. , le Cessie, S. , Rosendaal, F. R. , … Lamb, H. J. (2016). Association between hepatic triglyceride content and left ventricular diastolic function in a population‐based cohort: The Netherlands epidemiology of obesity study. Radiology, 279, 443–450. 10.1148/radiol.2015150035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. , Zhai, L. , & Zhang, D. (2014). Sleep duration and obesity among adults: A meta‐analysis of prospective studies. Sleep Medicine, 15, 1456–1462. 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi, B. , He, D. , Zhang, M. , Xue, J. , & Zhou, D. (2014). Short sleep duration predicts risk of metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 18, 293–297. 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, Y. , Chen, R. , & Yu, J. (2014). Sleep duration and abnormal serum lipids: The China Health and Nutrition Survey. Sleep Medicine, 15, 833–839. 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials