Abstract

Graves' disease (GD) is a common autoimmune cause of hyperthyroidism, which is eventually related to the generation of IgG antibodies stimulating the thyrotropin receptor. Clinical manifestations of the disease reflect hyperstimulation of the gland, causing thyrocyte hyperplasia (goiter) and excessive thyroid hormone synthesis (hyperthyroidism). The above clinical manifestations are preceded by still partially unraveled pathogenic actions governed by the induction of aberrant phenotype/functions of immune cells. In this review article we investigated the potential contribution of natural killer (NK) cells, based on literature analysis, to discuss the bidirectional interplay with thyroid hormones (TH) in GD progression. We analyzed cellular and molecular NK-cell associated mechanisms potentially impacting on GD, in a view of identification of the main NK-cell subset with highest immunoregulatory role.

Keywords: natural killer cells, Graves' disease, autoimmunity, hyperthyroidism, inflammation

The autoimmune thyroid disorder, known as Graves' disease (GD), is the most frequent cause of hyperthyroidism in iodine sufficient areas (1). Production of autoantibodies against the TSH-receptor (TRAb) represents the ultimate step for disease progression (2). Therefore, identification of the major drivers involved in triggering and progression of the disease, still represents an unmet need (1). There is a large consensus that identification of all potential factors involved in the pathogenesis of GD might favor the development of a more efficient treatment strategy, as well as of prevention approaches (3). This would be of paramount importance in view of the current lack of an effective pharmacological therapy for GD (4–6).

Natural killer (NK) cells, whose has been initially defined in virus clearance and defense against tumors, represent a highly heterogenous cell population. More recently, they have been shown to be involved in autoimmune disorders with both pathogenic and regulatory roles (7). While it is widely accepted that abnormalities in the adaptive immune response underpin autoreactivity and autoimmune diseases, it is also clear that other effector cells within the innate immunity compartment can act as relevant players. The major aim of this narrative review was to discuss the potential involvement of NK cells in the pathogenesis of Graves' disease and to speculate on potential future treatment/prevention strategies, based on NK cells as a target and/or as a tool for therapy.

Current Understanding of the Pathogenesis of Graves' Disease

Although GD can occur at any age and in both genders, it is more frequently observed in women in the 4–5th decade of life (1). The ultimate event is the continuous activation of the TSH-R on thyroid follicular cells by TRAb (8, 9). This dysregulated and continuous thyroid stimulation causes hyperthyroidism and, frequently, thyroid enlargement (goiter) (10, 11). As for other autoimmune disorders, GD likely results from the breakdown in the immune tolerance mechanisms, both at systemic (peripheral blood) and local (tissue) levels (8, 9). Failure of T regulatory (T reg) cell activity, proliferation of autoreactive T and B cells, and enhanced presentation of TSH-R (due to increased HLA-D affinity for TSH-R, more immunogenic TSH-R haplotype, or increased exposure of TSH-R peptide) drive the development of the disease (12, 13). Interestingly, TRAb has been detected in serum only shortly before diagnosis of GD (8).

Studies of dizygotic and monozygotic twins showed that genetic predisposition plays a relevant role in the development of GD (14, 15). Genetic risk factors for GD include multiple susceptibility genes, such as some HLA haplotypes (e.g., HLA DRB1*3, DQA1*5, DQB1*2), polymorphisms of genes involved in T and B cells regulation [Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4 (CTLA4), CD40, Protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 22 (PTPN22), the B cell survival factor (BAFF), Fas-ligand or CD95 and CD3γ], T reg cell functions (FOXp3), and polymorphisms of genes encoding for thyroid peptides (variants of thyroglobulin or TSH-R) (12, 16–21). Recently, a single polymorphism in tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) gene (rs1800629) was correlated with an increased risk to develop GD (22). GD is a heterogeneous disease, resulting from the combination of various and different gene polymorphisms, actually detectable by pooled genome wide association study (21–25). This would explain the weak overall size effect for genetic markers in genome-wide association studies (16, 21). Precipitating factors, probably inducing epigenetic changes include sex hormones, pregnancy, cigarette smoking, stress, infection, iodine, and other potential environmental factors (17, 26–33).

GD has been historically considered a T helper (Th)2-skewed disorder (34). This was supported by the starring role of B cells and by the features of Th cells infiltrating the thyroid gland, which are T cell clones specific for the TSH-R and mainly harbor Th2 cytokines (34, 35). More recently, Nagayama et al. demonstrated that the induction of immune shifting toward a Th2 phenotype in a GD mouse model was associated with a decrease, rather than an increase, in TRAb synthesis (36). This indirectly suggested a Th1 priority role in the induction of GD (35). In keeping with these findings, several studies showed that thyrostatic treatment with antithyroid drugs progressively induced transition from Th1 to Th2 predominance (37). As elegantly demonstrated by Rapaport and McLachlan, the fact that TRAb antibodies belong to the subclass of IgG, might explain the Th1-Th2 cytokine bias (38). Indeed, different IgG subclasses might coexist in several diseases and could additionally contribute to the pathogenic mechanisms (35–43). While early stage of the humoral immune response involves Th1 cytokines (e.g., IFN [interferon] γ), the prolonged immunization depends on IgG4 antibodies, driven by Th2 cytokines (e.g., interleukin [IL]-4) (39, 40). During a first phase, antigen presenting cells (APCs) and B cells-derived cytokines (IFNγ and TNFα) stimulate thyrocytes to secrete several chemokines, including C-X-C chemokine 10 that can recruit Th cells. Th cells interact with B cells to produce antibodies (1). Finally, intrathyroidal Th2 cells inhibit Th1 responses through the secretion of IL-10, IL-5, and IL-4 (38–46), thus preventing destruction of the thyroid gland, at variance with Hashimoto's thyroiditis. At this stage, thyroid gland might be protected from destruction both by inhibition of macrophages (from Th2 cytokines) and by upregulation of anti-apoptotic mechanisms (BCL-XL)/downregulation of Fas-Fas-ligand interaction (44, 45). Concomitantly, the increased Th2 response leads to an increased production of antibodies.

Natural Killer Cells and Their Role in Autoimmunity

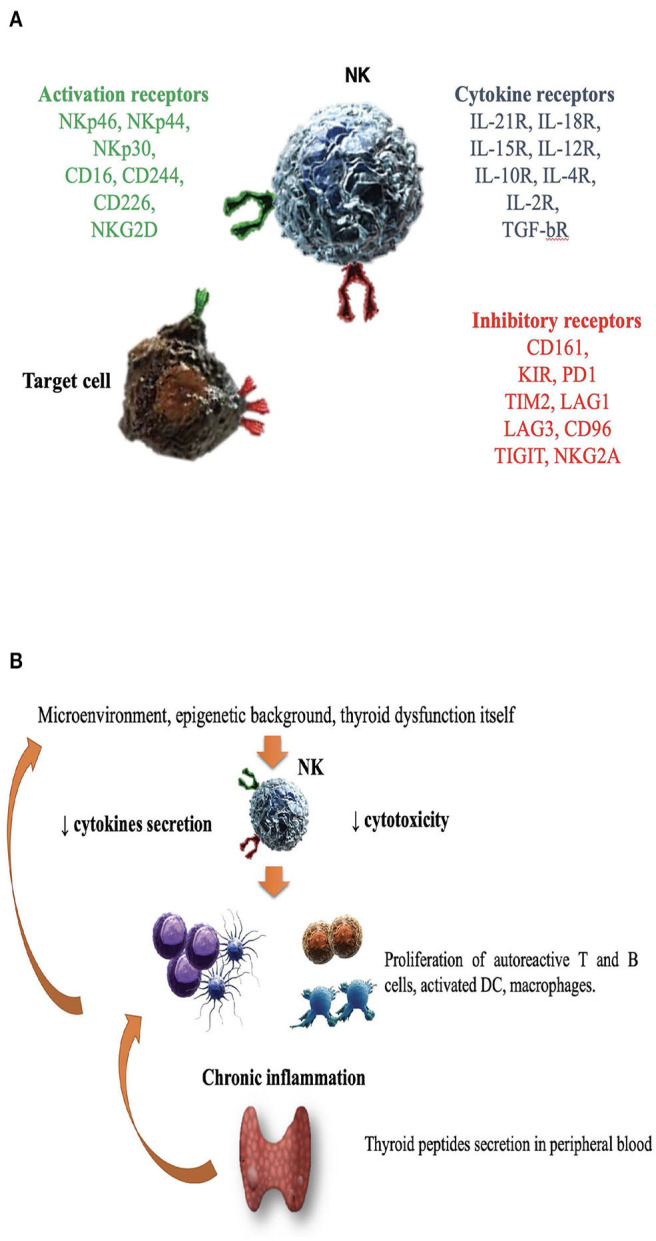

NK cells are large granular lymphocytes (LGL), recently classified as a subset of innate lymphoid cells (47). They are classically distinguished from the other mononuclear cells due to the expression of CD56, a molecule mediating homotypic adhesion, and null expression of CD3 (48). Additionally, based on the density of CD16 espression (a low-affinity receptor for the Fc portion of immunoglobulin G) and CD56 surface markers, NK cells could be further distinguished in two major subsets: CD56brightCD16dim/− and CD56dimCD16+cells (49– 51). According to a well-supported theory, NK cell precursors leave the bone marrow, transit through peripheral blood and reach the lymph nodes, where, under the influence of cytokines produced by stromal matrix, they differentiate into CD56+CD16− (49– 53). Maturation process is characterized by the down-regulation of CD56 and the acquisition of CD16 markers, as well as of “killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors” (KIRs), getting the features of CD56dimCD16+cells (50, 52–54). Therefore, CD56dimCD16+ NKs show high potential of cytotoxicity, due to the high content of cytolytic granules (containing perforin and granzyme), the high expression of KIRs, ILT2 (immunologlobulin-like transcript 2), and CD16 itself (51, 53). Conversely, CD56brightCD16dim/− are more immature cells, characterized by poor cytotoxic ability, high expression of inhibitory receptors (such as NKG2A), high ability to proliferate in response to IL-2 and elevated production of several cytokines, such as IFNγ, TNFα, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor, IL-10 and IL-13, depending on the conditions of stimulation (51, 55–58). It is the balance between inhibitory and activating signals, deriving from non-rearranged surface receptors, to dictate whether or not NK cells will kill target cells, engaged during their “patrolling” action (Figure 1A). Inhibitory receptors such as NKG2A, CD161, and inhibitory KIRs prevented the killing of normal cells, through the recognition of “self” molecules belonging to MHC class I. Thus, according to the “missing self-hypothesis,” NK cells recognize and attack target cells presenting low or aberrant MHC class I molecules (59). Furthermore, activating receptors, such as the natural cytotoxic receptors (NKp44, NKp46, NKp30), CD69, activating C-type lectin-like receptors (as the natural killer group 2D receptor) and activating KIRs recognize ligands induced on stressed cells (infected/overactive/transformed cells) and stimulate NK cells activation.

Figure 1.

The role of natural killer cells in the pathogenesis of Graves' disease. (A) Enumeration of activating/inhibitory receptors and cytokines receptors, whose signals determined NK cells activity in health and disease. CD, cluster of differentiation; CD16, Fc receptor; CD244, non MHC biding receptor acting as costimulatory ligand for NK cells; CD69, early expressed after NK cell activation; CD96, interacts with nectin and nectin-like proteins; CD161, recognizes the human NKR-P1A antigen; KIR, killer cell immunoglobulin like receptor; LAG1 and LAG3, lymphocyte activation gene 1 and 3; NKp30, NKp44, NKp46, the natural cytotoxic receptors (NCR); NKG2A and NKG2D, natural killer group 2A and 2D; TIGIT, T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain; IL (interleukin)-21/18/15/10/12/4/2 R (receptor); TGF-bR, TGF beta receptor family; PD1, programmed cell death protein 1; TIM2, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-containing domain 2; (B) Several factors including microenvironment, cytokines milieu, epigenetic background and hyperthyroidism itself might impair NK protective activity. DC, dendritic cells; NK, natural killer cells.

With the advent of the single cell technologies, coupled with RNA sequencing, it has been observed that NK cell heterogeneity, in term of subsets, is more complex (according to the different surface antigens and cytokine milieu) (60). This is not only a gene-restricted but also an environmental (re)-directed process (61–64). Modeling T cell classification, in humans, NK cells could be divided at least in two sets: “NK1,” characterized by the production of IFNγ and the regulatory “NK2” cells (65, 66). The polarization to NK2 phenotype depends on high IL4 levels and is characterized by the high production of “type 2” cytokines (i.g., IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13), the high expression of cytokines receptors and of NKG2A surface marker.

Considering their role in defense against viruses and that viral triggers are often involved in the initiation of several immune disorders, NK cells have been investigated for their role in autoimmunity (65–68). Indeed, CD56bright NK cells may orchestrate the overall immune process, influencing both innate and adaptive immune cells, through the integration of signals from numerous activating and inhibitory receptors. Due to the high plasticity and interaction with other immune and stromal cells, CD56bright NK cells acquire a regulatory role (65–69). In this context, a third subset, called “NK reg” has therefore been suggested and defined, according to surface inducible or constitutive markers such as CD117 (65–73). However, the available studies provided conflicting results, since, under some circumstances, NKs play a protective role, while in others they have been blamed to be pathogenic (7, 62, 68, 69). Likely, their action is correlated to the type of cell becoming the target of attack. In case of whether acquired or inherited dysfunctions, NK cells might participate into the destruction of non-transformed, healthy cells as the first step of the autoimmune process. Conversely, if targets are autoreactive T cells, dendritic cells (DC) or pro-inflammatory macrophages, NKs might act as regulators, dampening the inflammatory process (65, 69–73). Interestingly, NK cell regulatory activity has been demonstrated in several autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis (MS), experimental colitis or encephalitis (EE) and arthritis (RA), by different strategies such as cytokine release, interaction with ligands of the receptors NKG2D, NKG2A, NKp46 or perforin-mediated T cell death (63, 72, 73). In a mouse model, Ehelers and co-workers demonstrated that high levels of IL-18, which are found in Th1-skewed autoimmune process, induced the expression of CD117 on NKs which, in turn, became able to suppress CD8+T cells (73). In other experiments, CD56bright NK suppressed autologous CD4+ T cells proliferation through the expression of NKp30 and NKp46, granzyme B releasing and immunosuppressive molecule adenosine (72, 73). In experimental models of autoimmune EE, the inhibitory role of NKs on the T effectors proliferation, as well as a direct cytotoxic effect on autoreactive specific T cells, were shown (74). Likewise, Takahashi et al. demonstrated, in MS patients, that CD56bright NK could favor clinical remission, by suppressing the production of IFNγ, by specific autoreactive T effectors and secreting IL-5 (57, 69, 75). Laroni et al. observed that CD56bright NK cells had reduced ability to kill T-cells in MS patients, compared to healthy controls, possibly due to an increased expression of NKG2A (69, 76). Thus, impaired cytotoxicity or the inability to secrete cytolytic granules have been correlated to the escape of proinflammatory cells (both T and B lymphocytes, DC and macrophages) from regulatory mechanisms of controls (77). In other cases, such as RA, loss of NK tolerance (due to decreased inhibitory signals or inappropriate stimulation of activating signals) might favor the development of autoimmune diseases. Different mechanisms have been blamed, such as the presence of antilymphocyte antibodies (78). In other disorders, such as myasthenia gravis and EE, NK cells seem to facilitate initiation and progression of autoimmunity (67, 68). Besides differences in the strains and models used, several factors may influence the specific, and even contradictory, actions of NK cells. Their ability to adapt to different stimuli and different anatomical localization may play an important role. Microenvironment itself may influence NK functions, such as migration and tissue retentions, as it emerged in the complex interaction with DC, influenced by density, maturation state and phenotype of this population (68). Epigenetic modifications strongly influence NK cells all along their life, from development to regulation and differentiation of effector functions (79–81). Epigenetic remodeling, acquired through immunological experiences, might modulate NK functions (61). For instance, gene expression of several genes (including KIRs) is regulated by DNA methylation (hypomethylation or hypermethylation) of their promoters. The interindividual genetic variability in the receptor repertoire, especially of the highly polymorphic KIR gene, influence the recognition of target cells (80). KIRs polymorphisms might influence the engagement with HLA molecules and, as counterpart, functional interaction between co-inherited KIRs (especially inhibitory KIRs) and HLA progressively influence NK education (81). Besides KIRs, other receptors such as NKG2A are involved in NK education (61).

The Link Between Leukocytes and Thyroid Hormones

A possible link between THs and the immune system was already suggested more than 40 years ago, by the discovery that Staphylococcus-stimulated lymphocytes might de novo synthesize a TSH-like substance (immunoreactive TSH, i-TSH), similar to the pituitary-released form and possibly involved in autoimmune thyroid disorders (AITD) (82). Further experiments progressively demonstrated that bone marrow hematopoietic cells, lymphocytes, DC and even intestinal epithelial cells, could synthesize TSH (83). The role of extra-pituitary TSH remains to be clarified. It was speculated that, as pituitary TSH, i-TSH might stimulate the synthesis of TH, which, in turn, might influence the immune system (indirect effect). Several papers showed that immune cells harbor essential elements required for THs metabolism and action. For example, both neutrophils and DC express T3 (the active form of TH) transporters (MCT10 in human) and type 2 and 3 deiodinases (involved in THs synthesis) (84–86). Indeed, it has been widely demonstrated that THs interact with hematopoietic cells (85–90) at different levels. T3 might affect target immune cells by binding both to nuclear receptors (thyroid hormones receptors TRα and TRβ) and membrane receptors (86–90). For example, TH and especially T3 can influence maturation of DCs (84, 85). DC phenotype was studied in thyroidectomized patients before and after levothyroxine supplementation, showing that THs induce an increase in DCs number and influence their functions (91). A research group from Cordoba demonstrated that T3 induce DCs activation through Akt and NF-kB pathways, driving the immune response toward a Th1 phenotype (92, 93). Further support to the regulatory role of TH came from experiments showed that daily administration of T4 was followed by the complete restoration of the immune competence in thyroidectomized mice (94). Furthermore, T4 treatment in mice enhanced the NKs cytotoxic activity against classical target cells, amplifying their responsiveness to cytokines and modulating NK metabolic properties (95). Some years later, Provinciali et al. demonstrated that, after T4 pre-treatment, the peak of NK cytotoxic activity was achieved using half the optimal IFNγ concentration (96). Additional experiments strengthen the hypothesis of a paracrine TSH-pathway (97–99). TSH-R is expressed on myeloid and lymphoid cells (100, 101). By its stimulation, TSH (both the immune and the pituitary released forms) may act as a cytokine-like regulatory molecule and induce the secretion of several cytokines, such as TNFα (102, 103). In vitro studies showed that TSH, combined to classical cytokines (as IL-2, IL-12, IL-1β), acts as co-stimulus improving lymphocytes and NKs proliferative response to even low dose of mitogens (103, 104). Todd et al. demonstrated that TSH was able to enhance the expression of MHC class II in thyroid cells treated with IFNγ (105). Accordingly, Dorshkind et al. demonstrated that THs induce the synthesis of cytokines and the expression of IL-2 receptor in NK cells (106). Indeed, while both T3 and FT4 boosted the IFNγ response in mice (107, 108), T4 amplified both IFNγ and IL-2 (96).

Based on the bidirectional relationship between TH and the immune system (96), Kmiec et al. postulated that in the elderly the reduction of TH with aging might be involved in the impairment of NK activity by T3 administration; they found a direct correlation between serum T3 levels and NK activity, in spite of conserved proportion of circulating NK cells (109, 110). Indeed, NK cell activity was selectively improved by T3 administration in those subjects having T3 levels in the slower range.

Natural Killer Cells and Graves' Disease

From a mutual perspective, thyroid function might orchestrate the immune response and, conversely, dysfunction of the immune system might favor the development of thyroid disorders. Several studies investigated the potential contribution of NKs in the development and/or progression of GD, but results are still inconclusive and sometimes conflicting. Table 1 reports the available data on this issue (111–123). Researchers from Osaka University observed that the total percentage of LGL, including NK-like cells, was decreased in untreated GD patients compared to euthyroid GD patients on antithyroid drug therapy and to controls; in addition, the proportion of LGL was inversely correlated to T4 and T3 levels (110–112, 123). Thus, while normal THs levels are crucial to maintain an adequate activity of the immune system, supraphysiological THs levels exerted a detrimental effect, mimicking starvation, and increased cortisol secretion (121, 124–126). Immunocomplexes able to suppress NK cell activity, as in other autoimmune disorders (e.g., RA), were considered as a possible cause of this phenomenon (76, 127). According to a different hypothesis, the decrease of NK cells might be the primary immunological abnormality in the pathogenesis of GD (111, 127).

Table 1.

Summary of studies investigating the role of natural killer cells in Graves' disease.

| References | Subjects | Study objects | Methods | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino et al. (111) | GD (16 untreated GD + 11 hyperGD under ATD + 3 euGD under ATD + 4 remission GD) vs. 43 controls vs. 14 HT | K lymphs | Peripheral blood samples |

↓ K lymphs in hyperGD than controls ↓ plaque forming K lymphs in hyperGD than controls No differences in K lymphs comparing euGD to controls. |

| Iwatani et al. (112) | GD (12 hyperGD + 5 euGD) vs. HT (17 euHT + 4 hypoHT) vs. 55 controls | LGL | Peripheral blood samples | LGL ↓↑FT4, FT3 in hyperGD ↓LGL in hyperGD compared to other groups |

| Stein-Streilein et al. (113) | Mice fed with T4 vs. hypothyroid (due to ATD) vs. euthyroid mice | NK release of lytic factors | Blood, spleen and lung samples after 2 and 6 w | ↓lytic molecules release in thyrotoxic mice |

| Papic et al. (114) | 22 untreated GD vs. 18 hyperthyroxinemic for T4 treatment | cNK number and activity | Peripheral blood samples Release assay for NK cytotoxicity against K562 |

↓cytotoxicity in hyperthyroidism (both groups) ↓ability of IL-2 chance to enhance NK activity in GD |

| Wang et al. (115) | GD (33 untreated GD + 19 euGD under ATD + 6 euGD after ATD withdrawal) vs. 43 controls | cNK number, cytotoxicity | Peripheral blood samples Release assay for NK cytotoxicity against K562 |

No differences in cNK number in GD compared to controls. ↓cytotoxicity in untreated GD or during ATD treatment vs. euGD |

| Pedersen et al. (116) | 20 untreated GD vs. 11 HT vs. 10 non-toxic goiter vs. 22 controls | cNK number, cytotoxicity | Co-culture with IL-2, IFN, indomethacin Release assay for NK cytotoxicity against K562 |

No differences in cNK number and activity in AITD vs. controls |

| Lee et al. (117) | 18 untreated GD vs. 18 controls | cNK cytotoxicity | Co-culture with T4 Release assay for NK cytotoxicity against K562 |

No differences in cNK activity in GD vs. controls↑ cytotoxicity with T4 in controls but not in GD |

| Hidaka et al. (118) | 25 untreated GD vs. 18 HT vs. 22 postpartum AITD vs. 61 controls | cNK cytotoxicity | Peripheral blood samples Release assay for NK cytotoxicity against K562 |

↑cytotoxicity in GD vs. other groups |

| Aust et al. (119) | 10 GD | tNK and cNK number | Thyroid tissues and peripheral blood samples | tNK↑↑ AbTPO |

| Wenzel et al. (120) | 40 GD vs. 26 HT vs. 32 controls | cNK cytotoxicity | Peripheral blood samples Release assay for NK cytotoxicity against K562 |

↓ cytotoxicity in untreated/under ATD GD vs. controls |

| Solerte et al. (121) | 13 untreated GD vs. 11 hypoHT vs. 15 controls | Functional studies | cNK were incubated with IL-2, TGF-β and DHEAS Release assay for NK cytotoxicity against K562 Cytokine secretion |

↓cytotoxicity induced by IL2 e TGF-β in GD and HT ↓spontaneous and IL2 induced TNFα release |

| Dastmalchi et al. (80) | 8 untreated GD vs. 176 controls | KIR genes and related HLA polymorphisms | Peripheral blood samples PCR-SSP |

No evident correlations |

| Zhang et al. (122) | 28 untreated GD vs. 23 controls | Functional and phenotypic studies | Peripheral blood samples |

↓cytotoxicity in GD vs. controls ↓NKG2D+, NKG2C+, NKp30+, NKG2A+ NK in GD vs. controls ↓IFNγ in GD vs. controls NKG2A+ NK ↓↑TRAb NKG2D+ NK ↓↑TH |

AITD, autoimmune thyroid disorders; ATD, antithyoid drugs; cNK, circulating NK cells; eu, euthyroidism; d, days; HT, Hashimoto's thyroiditis; IFN-γ, interferon γ; K lymphs, killer lymphocytes; LGL, large granular lymphocytes; NKG2 A/C/D, natural killer group 2D, belonging to C-type lectin like receptors; PCR-SSP, polymerase chain reaction sequence-specific primer directed method; tNK, tissutal (intrathyroidal) NK cells; TH, thyroid hormones; w, weeks; ↑ enhance; ↓ depress; ↑↑ direct correlation; ↓↑ inverse correlation.

Solerte et al. reported that both spontaneous and IL-2/IFNβ-modulated NK cells cytotoxicity (NKCC), as well as spontaneous and IL-2 induced TNFα release were decreased in NK cells from 13 GD patients compared to 15 controls (121). Both cytokines secretion and cytotoxicity were promptly normalized by co-incubating NKs with DHEAS (dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate), supporting the concept of a concomitant effect of other endocrine axes (121, 128, 129). Studies from the University of Miami comparing thyrotoxic mice (due to levothyroxine treatment) to euthyroid or hypothyroid (due to antithyroid drug treatment) control mice observed a reduced secretion of cytolytic granules (113). Similar results were obtained from the same group in humans (see Table 1) (114), with a reduction in cytotoxicity, studied by release assay for NK cell cytotoxicity against K562 tumor target cells.

Considering that NK cell activity is affected by age (130), a study compared NKCC in AITD patients with age and gender-matched healthy controls, demonstrating an impaired NK cell activity in AITD (120). As previously outlined, the integration of activating and inhibitory signals from NK surface regulates NK cells effector functions, such as cytokine secretion and NKCC. In a study of 28 newly onset GD patients, Zhang et al. observed a reduction of NK cells expressing both activating (NKG2D, NKG2C, NKp30) and inhibitory receptors (NKG2A) compared to matched healthy controls (122). Additionally, NKG2A+ NKs were inversely related to TRAb levels, while NKG2D+ NKs were inversely related to serum free T4 levels (122), supporting the role of dysfunctional NK cells. Figure 1B illustrates the hypothesis that in case of dysfunctional impairment, NK cells lose their ability to protect from the development of GD. Other studies (115, 117, 119, 120, 122, 131, 132), with some exceptions (116, 118) generally agreed on the impairment of NK activity in GD and reported that restoration of euthyroidism by antithyroid drug treatment (especially propylthiouracil) could improve NK functionality (133, 134).

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

It is now clear the immune system, both the innate and the adaptive components, are crucial host-related orchestrators of disorder induction/insurgence and progression. Alterations of immune cell phenotype and functions, as a consequence of chronic inflammation, are shared features between cancers, cardiovascular, neurological, and autoimmune diseases. In the new era of immunotherapy, most of the efforts are addressed to cancer, as supported by the vast literature and clinical trials (135). This rapidly developing field suggests the same attention should be dedicated also to autoimmunity, that still requires a better understanding of the cellular and molecular events occurring during autoimmune disorders, including GD. Unveiling these mechanisms and events is required to identify new immunological cellular biomarkers, trace disease progression, and design new targeted therapeutic strategies for autoimmunity. In this scenario, re-education/manipulation of NK cells appear as a promising strategy, as confirmed by the growing interest in CAR-NK cells (136).

Author Contributions

DG, LM, EP, and AB conceived the manuscript. All the authors took part in manuscript writing and editing. EP, LB, LM, and AB supervised the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was partly supported by University of Insubria intramural grant FAR 2019 and MIUR Funding for Basic Research Activities FFABR 2017 to LM and by grants from the Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR, Roma) to LB and from the University of Insubria to LB and EP. AB has received funding from AIRC under MFAG 2019- ID 22818-PI. AB is supported by Italian Ministry of Health Ricerca Corrente-IRCCS MultiMedica. DG was supported by a University of Insubria Ph.D. scholarship in Experimental and Translational Medicine, whereas MG was a recipient of Ph.D. course in Life Sciences and Biotechnology at the University of Insubria.

References

- 1.Smith TJ, Hegedüs L. Graves' disease. N Engl J Med. (2016) 375:1552–65. 10.1056/NEJMra1510030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies TF, Latif R. Editorial: TSH receptor and autoimmunity. Front Endocrinol. (2019) 10:19. 10.3389/fendo.2019.00019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanda ML, Piantanida E, Lai A, Lombardi V, Dalle Mule I, Liparulo L, et al. Thyroid autoimmunity and environment. Horm Metab Res. (2009) 41:436–42. 10.1055/s-0029-1215568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masiello E, Veronesi G, Gallo D, Premoli P, Bianconi E, Rosetti S, et al. Antithyroid drug treatment for Graves' disease: baseline predictive models of relapse after treatment for a patient-tailored management. J Endocrinol Invest. (2018) 41:1425–32. 10.1007/s40618-018-0918-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piantanida E, Lai A, Sassi L, Gallo D, Spreafico E, Tanda ML, et al. Outcome prediction of treatment of Graves' hyperthyroidism with antithyroid drugs. Horm Metab Res. (2015) 47:767–72. 10.1055/s-0035-1555759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartalena L, Piantanida E, Tanda ML. Can a patient-tailored treatment approach for Graves' disease reduce mortality? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2019) 7:245–6. 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30057-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zitti B, Bryceson YT. Natural killer cells in inflammation and autoimmunity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. (2018) 42:37–46. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morshed SA, Latif R, Davies TF. Delineating the autoimmune mechanisms in Graves' disease. Immunol Res. (2012) 54:191–203. 10.1007/s12026-012-8312-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonelli A, Fallahi P, Elia G, Ragusa F, Paparo SR, Ruffilli I, et al. Graves' disease: clinical manifestations, immune pathogenesis (cytokines and chemokines) and therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2020). 34:101388. 10.1016/j.beem.2020.101388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartalena L, Masiello E, Magri F, Veronesi G, Bianconi E, Zerbini F, et al. The phenotype of newly diagnosed Graves' disease in Italy in recent years is milder than in the past: results of a large observational longitudinal study. J Endocrinol Invest. (2016) 39:1445–51. 10.1007/s40618-016-0516-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valente WA, Vitti P, Rotella CM, Vaughan MM, Aloj SM, Grollman EF, et al. Antibodies that promote thyroid growth. A distinct population of thyroid stimulating autoantibodies. N Engl J Med. (1983) 309:1028–34. 10.1056/NEJM198310273091705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLachlan S, Rapoport B. Breaking tolerance to thyroid antigens: changing concepts in thyroid autoimmunity. Endocr Rev. (2014) 35:59–151. 10.1210/er.2013-1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Z, Wang Y, Ding X, Zhang M, He M, Zhao Y, et al. The proportion of peripheral blood tregs among the CD4+ T cells of autoimmune thyroid disease patients: a meta-analysis. Endocr J. (2020) 67:317–26. 10.1507/endocrj.EJ19-0307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brix TH, Kyvik KO, Christensen K, Hegedüs L. Evidence for a major role of heredity in Graves' disease: a population-based study of two danish twin cohorts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2001) 86:930–34. 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brix TH, Hegedüs L. Twin studies as a model for exploring the aetiology of autoimmune thyroid disease. Clin Endocrinol. (2012) 76:457–64. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04318.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vejrazkova D, Vcelak J, Vaclavikova E, VanKova M, Zajickova K, Duskova M, et al. Genetic predictors of the development and recurrence of Graves' disease. Physiol Res. (2018) 67:S431–9. 10.33549/ehysiolres.934018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antonelli A, Ferrari SM, Ragusa F, Ragusa F, Paparo SR, Ruffilli I, et al. Graves' disease: epidemiology, genetic and environmental risk factors and viruses. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2020) 4:101387. 10.1016/j.beem.2020.101387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pujol-Borrell R, Álvarez-Sierra D, Jaraquemada D, Marín-Sánchez A, Colobran R. Central tolerance mechanisms to TSHR in Graves' disease: contributions to understand the genetic association. Horm Metab Res. (2018) 50:863–70. 10.1055/a-0755-7927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latif R, Mezei M, Morshed SA, Ma R, Ehrlich R, Davies TF. A modifying autoantigen in Graves' disease. Endocrinology. (2019) 160:1008–20. 10.1210/en.2018-01048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe A, Inoue N, Watanabe M, Yamanoto M, Ozaki H, Hidaka Y, et al. Increases of CD80 and CD86 Expression on peripheral blood cells and their gene polymorphisms in autoimmune thyroid disease. Immunol Invest. (2020) 49:191–203. 10.1080/08820139.2019.1688343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lane LC, Allinson KR, Campbell K, Bhatnagar I, Ingoe L, Razvi S, et al. Analysis of BAFF gene polymorphisms in UK Graves' disease patients. Clin Endocrinol. (2019) 90:170–4. 10.1111/cen.13872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tu Y, Fan G, Zeng T, Cai X, Kong W. Association of TNF-α promoter polymorphism and Graves' disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Biosci Rep. (2018) 38:BSR20180143. 10.1042/BSR20180143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Truja T, Kutz A, Fischli S, Meier C, Mueller B, Recher M, et al. Is Graves' disease a primary immunodeficiency? New immunological perspectives on an endocrine disease. BMC Med. (2017) 15:174. 10.1186/s12916-017-0939-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shao X, Wang B, Mu K, Li, Li L Q, Jia X, et al. Key gene co-expression modules and functional pathways involved in the pathogenesis of Graves' disease. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2018) 474:252–9. 10.1016/j.mce.2018.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khong JJ, Burdon KP, Lu Y, Laurie K, Leonardos L, Baird PN, et al. Pooled genome wide association detects association upstream of FCRL3 with Graves' disease. BMC Genomics. (2016) 17:939. 10.1186/s12864-016-3276-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Croce L, Di Dalmazi G, Orsolini F, Virili C, Brigante G, Gianetti E, et al. Graves' disease and the post-partum period: an intriguing relationship. Front Endocrinol. (2019) 10:853. 10.3389/fendo.2019.00853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papanastasiou L, Vatalas IA, Koutras DA, Mastorakos G. Thyroid autoimmunity in the current iodine environment. Thyroid. (2007) 17:729–39. 10.1089/thy.2006.0299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vestegard P. Smoking and thyroid disorders–a meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol. (2002) 146:153–61. 10.1530/eje.0.1460153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim SJ, Kim MJ, Yoon SG, Myong JP, Yo HW, Chai YJ, et al. Impact of smoking on thyroid gland: dose-related effect of urinary cotinine levels on thyroid function and thyroid autoimmunity. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:4213. 10.1038/s41598-019-40708-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallo D, Cattaneo SAM, Piantanida E, Mortara L, Merletti F, Nisi M, et al. Severità del morbo di basedow di prima diagnosi: ruolo dei linfociti T reg e dei micronutrienti. Dati preliminari di uno studio osservazionale pilota. Lettere GIC. (2019) 28:15–19. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marinò M, Menconi F, Rotondo Dottore G, Leo M, Marcocci C. Selenium in Graves' hyperthyroidism and orbitopathy. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. (2018) 34:S105–10. 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gallo D, Mortara L, Gariboldi MB, Cattaneo SAM, Rosetti S, Gentile L, et al. Immunomodulatory effect of vitamin D and its potential role in the prevention and treatment of thyroid autoimmunity: a narrative review. J Endocrinol Invest. (2020) 43:413–29. 10.1007/s40618-019-01123-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ponzetto A, Figura N. Clinical phenotype of Graves' disease. J Endocrinol Invest. (2020) 10.1007/s40618-020-01214-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McIver B, Morris JC. The pathogenesis of Graves' disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. (1998) 27:73–89. 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70299-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicholson LB, Kuchroo VK. Manipulation of the Th1/Th2 balance in autoimmune disease. Curr Opin Immunol. (1996) 8:837–42. 10.3109/08916939608995329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagayama Y, Mizuguchi H, Hayakawa T, Niwa M, McLachlan SM, Rapoport B. Prevention of autoantibody-mediated graves'-like hyperthyroidism in mice with IL-4, a Th2 cytokine. J Clin Invest. (2003) 170:3522–7. 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshihisa I, Atsushi M, Naoto S, Yoshimasa A. Changes in expression of T-helper (Th) 1- and Th2-associated chemokine receptors on peripheral blood lymphocytes and plasma concentrations of their ligands, interferon-inducible protein-10 and thymus and activation-regulated chemokine, after antithyroid drug administration in hyperthyroid patients with Graves' disease. Eur J Endocrinol. (2007) 156:623–30. 10.1530/EJE-07-0019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rapoport B, McLachlan SM. Graves' hyperthyroidism is antibody-mediated but is predominantly a Th1-type cytokine disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2014) 99:4060–61. 10.1210/jc.2014-3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giusti C. The Th1 chemokine MIG in Graves' disease: a narrative review of the literature. Clin Ter. (2019) 170:e285–90. 10.7417/CT.2019.2149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toellner KM, Luther SA, Sze DM, Choy RK, Taylor DR, MacLennan IC, et al. T helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 characteristics start to develop during T cell priming and are associated with an immediate ability to induce immunoglobulin class switching. J Exp Med. (1998) 187:1193–204. 10.1084/jem.187.8.1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu X, Peng S, Wang X, Shan Z, Teng W. Decreased expression of FcγRII in active Graves' disease patients. J Clin Lab Anal. (2019) 33:e22904. 10.1002/jcla.22904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mullins RJ, Cohen SB, Webb LM, Chernajovsky Y, Dayan CM, Londei M, et al. Identification of thyroid stimulating hormone receptor-specific T cells in Graves' disease thyroid using autoantigen-transfected epstein-barr virus-transformed B cell lines. J Clin Invest. (1995) 96:30–37. 10.1172/JCI118034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koneczny I. A new classification system for IgG4 autoantibodies. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:97. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fountoulakis S, Vartholomatos G, Kolaitis N, Frillingos S., Philippou G, Tsatsoulis A. Differential expression of Fas system apoptotic molecules in peripheral lymphocytes from patients with Graves' disease and hashimoto's thyroiditis. Eur J Endocrinol. (2008) 158:853–9. 10.1530/EJE-08-0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stassi G, de Maria R. Autoimmune thyroid disease: new models of cell death in autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. (2002) 2:195–204. 10.1038/nri750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fallahi P, Ferrari SM, Ragusa F, Ruffini I, Elia G, Paparo SR, et al. Th1 chemokines in autoimmune endocrine disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2020) 105:dgz289. 10.1210/clinem/dgz289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sciumé G. Innate lymphocytes: development, homeostasis, and disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. (2018) 42:1–4. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2018.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crinier A, Narni-Mancinelli E, Ugolini S, Vivier E. Snapshot: natural killer cells. Cell. (2020) 180:1280.e1. 10.1016/j.cell2020.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cichocki F, Grzywacz B, Miller JS. Human NK cell development: one road or many? Front Immunol. (2019) 10:2078 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan A, Hong DL, Atzberger A, Briquemont B, Iserentant G, Ollert M, et al. CD56bright human NK cells differentiate into CD56dim cells: role of contact with peripheral fibroblasts. J Immunol. (2007) 179:89–94. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sivori S, Vacca P, Del Zotto G, Munari E, Migari MC, Moretta L. Human NK cells: surface receptors, inhibitory checkpoints, translational applications. Cell Mol Immunol. (2019) 16:430–41. 10.1038/s41423-019-0206-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romagnani C, Juelke K, Falco M, Morandi B, D'Agostino A, Costa R, et al. CD56brightCD16- killer Ig-like receptor- NK cells display longer telomeres and acquire features of CD56dim NK cells upon activation. J Immunol. (2008) 178:4947–55. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.4947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bozzano F, Perrone C, Moretta L, De Maria A. NK cell precursors in human bone marrow in health and inflammation. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:2045. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moretta L. Dissecting CD56dim human NK cells. Blood. (2010) 116:3689–91. 10.1182/blood-2010-09-303057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poli A, Michel T, Thérésine M, Andrès E, Hentges F, Zimmer J. CD56bright natural killer (NK) cells: an important NK cell subset. Immunology. (2009) 126:458–65. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03027.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michel T, Poli A, Cuapio A, Briquemont T, Iserentat G, Ollert M, et al. Human CD56bright NK cells: an update. J Immunol. (2016) 196:2923–31. 10.4049/jimmunol.1502570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morandi F, Horenstein AL, Chillemi A, Quarona V, Chiesa S, Imperatori A, et al. CD56bright CD16-NK cells produce adenosine through a CD38-mediated pathway and act as regulatory cells inhibiting autologous CD4+ T cell proliferation. J Immunol. (2015) 195:965–72. 10.4049/jimmunol.1500591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Melsen JE, Lugthart G, Lankester AC, Schilham MW. Human circulating and tissue-resident CD56(bright) natural killer cell populations. Front Immunol. (2016) 7:262. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pegram HJ, Andrews DM, Smyth MJ, Darcy PK, Kershaw MH. Activating and inhibitory receptors of natural killer cells. Immunol Cell Biol. (2011) 89:216–24. 10.1038/icb.2010.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Freud AG, Mundy-Bosse BL, Yu J, Caligiuri MA. The broad spectrum of human natural killer cell diversity. Immunity. (2017) 47:820–33. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boudreau JE, Hsu KC. Natural killer cell education in human health and disease. Curr Opin Immunol. (2018) 50:102–11. 10.1016/j.coi.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Varchetta S, Oliviero B, Mavilio D, Mondelli MU. Different combinations of cytokines and activating receptor stimuli are required for human natural killer cell functional diversity. Cytokine. (2013) 62:58–63. 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumar S. Natural killer cell cytotoxicity and its regulation by inhibitory receptors. Immunology. (2018) 154:383–93. 10.1111/imm.12921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Collins PL, Cella M, Porter SI, Li S, Gurewitz G, Hong HS, et al. Gene regulatory programs conferring phenotypic identities to human NK cells. Cell. (2019) 176:348–60.e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang C, Zhang J, Tian Z. The regulatory effect of natural killer cells: do “NK-reg cells” exist? Cell Mol Immunol. (2006) 3:241–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Deniz G, Akdis M, Aktas E, Blaser K, Akdis C. Human NK1 and NK2 subsets determined by purification of IFN-γ-secreting and IFN-γ-nonsecreting NK cells. Eur J Immunol. (2002) 32:879–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gianchecchi E, Delfino DV, Fierabracci A. NK cells in autoimmune diseases: linking innate and adaptive immune responses. Autoimmun Rev. (2018) 17:142–54. 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Poggi A, Zocchi MR. NK cell autoreactivity and autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. (2014) 5:27. 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Laroni A, Armentani E, Kerlero de Rosbo N, Ivaldi F, Marcenaro E, Sivori S, et al. Dysregulation of regulatory CD56bright NK cells/T cells interactions in multiple sclerosis. J Autoimmun. (2016) 72:8–18. 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Johansson S, Berg L, Hall H, Höglund P. NK cells: elusive players in autoimmunity. Trends Immunol. (2005) 26:613–18. 10.1016/j.it.2005.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferlazzo G, Morandi B. Cross-talks between natural killer cells and distinct subsets of dendritic cells. Front Immunol. (2014) 5:159. 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Crome SQ, Lang PA, Lang KS, Ohashi PS. Natural killer cells regulate diverse T cell responses. Trends Immunol. (2013) 34:342–9. 10.1016/j.it.2013.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ehlers M, Papewalis C, Stenzel W, Jacobs B, Meyer KL, Deenen R, et al. Immunoregulatory natural killer cells suppress autoimmunity by down-regulating antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in mice. Endocrinology. (2012) 153:4367–79. 10.1210/en.2012-1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smeltz RB, Wolf NA, Swanborg RH. Inhibition of autoimmune T cell responses in the DA rat by bone marrow-derived NK cells in vitro: implications for autoimmunity. J Immunol. (1999) 163:1390–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Takahashi K, Aranami T, Endoh M, Miyake S, Yamamura T. The regulatory role of natural killer cells in multiple sclerosis. Brain. (2004) 127:1917–27. 10.1093/brain/awh219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mimpen M, Smolders J, Hupperts R, Damoiseaux J. Natural killer cells in multiple sclerosis: a review. Immunol Lett. (2020) 222:1–11. 10.1016/j.imlet.2020.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schleinitz N, Vély F, Harlé JR, Vivier E. Natural killer cells in human autoimmune diseases. Immunology. (2010) 131:451–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03360.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li C, Mu R, Lu XY, He J, Jia RL, Li ZG. Antilymphocyte antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus: association with disease activity and lymphopenia. J Immunol Res. (2014) 2014:67212. 10.1155/2014/672126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Castriconi R, Carrega P, Dondero A, Bellora F, Casu B, Regis S, et al. Molecular mechanisms directing migration and retention of natural killer cells in human tissues. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:2324. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dastmalchi R, Farazmand A, Noshad S, Mozafari M, Mahmoudi M, Esteghamati A, et al. Polymorphism of killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) and their HLA ligands in Graves' disease. Mol Biol Rep. (2014) 41:5367–74. 10.1007/s11033-014-3408-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schenk A, Bloch W, Zimmer P. Natural killer cells-an epigenetic perspective of development and regulation. Int J Mol Sci. (2016) 17:326. 10.3390/ijms17030326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smith EM, Phan M, Kruger TE, Coppenhaver DH, Blalock JE. Human lymphocyte production of immunoreactive thyrotropin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1982) 80:6010–13. 10.1073/pnas.80.19.6010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang HC, Drago J, Zhou Q, Klein JR. An intrinsic thyrotropin-mediated pathway of TNFα production by bone marrow cells. Blood. (2003) 101:119–23. 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mooij P, Simons PJ, de Haan-Meulman M, de Wit HJ, Drexhage HA. Effect of thyroid hormones and other iodinated compounds on the transition of monocytes into veiled/dendritic cells: role of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, tumour-necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6. J Endocrinol. (1994) 140:503–12. 10.1677/joe.0.1400503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Montesinos MDM, Pellizas CG. Thyroid hormone action on innate immunity. Front Endocrinol. (2019) 10:486 10.3389/fendo.2019.00486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.van Der Spek AH, Fliers E, Boelen A. Thyroid hormone metabolism in innate immune cells. J Endocrinol. (2017) 232:R67–R81. 10.1530/JOE-16-0462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.De Vito P, Incerpi S, Pedersen JZ, Luly P, Davis FB, Davis PJ. Thyroid hormones as modulators of immune activities at cellular level. Thyroid. (2011) 8:879–90. 10.1089/thy.2010.0429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Angelin-Duclos C, Domenget C, Kolbus A, Beug H, Jurdic P, Samarut J. Thyroid hormone T3 acting through the thyroid hormone α receptor is necessary for implementation of erythropoiesis in the neonatal spleen environment in the mouse. Development. (2005) 132:925–34. 10.1243/dev.01648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pallinger E, Kovacs P, Csaba G. Presence of hormones (triiodothyronine, serotonin and histamine) in the immune cells of newborn rats. Cell Biol Int. (2005) 29:826–30. 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Csaba G, Kovacs P, Pallinger E. Effect of the inhibition of triiodothyronine (T3) production by thiamazole on the T3 and serotonin content of immune cells. Life Sci. (2011) 76:2043–52. 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dedecjus M, Stasiolek M, Brzezinski J, Selmaj K, Lewinski A. Thyroid hormones influence human dendritic cells' phenotype, function, subsets distribution. Thyroid. (2010) 21:533–40. 10.1089/thy.2010.0183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mascanfroni ID, Montesinos, Mdel M, Alamino VA, Susperreguy S, Nicola JP, et al. Nuclear factor (NF)-kappa B-dependent thyroid hormone receptor beta1 expression controls dendritic cell function via Akt signaling. J Biol Chem. (2010) 285:9569–82. 10.1074/jbc.M109.071241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mascanfroni I, Montesinos, Mdel M., Susperreguy S, Cervi L, Ilarregui JM, et al. Control of dendritic cell maturation and function by triiodothyronine. Faseb J. (2008) 22:1032–42. 10.1096/fj.078652com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fabris N. Immunodepression in thyroid-deprived animals. Clin ExpI Immunol. (1973) 15:601–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sharma SD, Tsai V, Proffitt MR. Enhancement of mouse natural killer cell activity by thyroxine. Cell Immunol. (1982) 73:83–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Provinciali M, Muzzioli M, Fabris N. Thyroxine-dependent modulation of natural killer activity. J Exp Pathol. (1987) 3:617–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Klein JR, Wang HC. Characterization of a novel set of resident intrathyroidal bone marrow-derived hematopoietic cells: potential for immune-endocrine interactions in thyroid homeostasis. J Exp Biol. (2004) 207:55–65. 10.1242/jeb.00710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kruger TE, Blalock JE. Cellular requirements for thyrotropin enhancement of in vitro antibody production. J Immunol. (1986) 137:197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kruger TE, Smith EM, Harbour DV, Blalock JE. Thyrotropin: an endogenous regulator of the in vitro immune response. J Immunol. (1989) 142:744–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bagriacik EU, Klein JR. The thyrotropin (thyroid stimulating hormone) receptor is expressed on murine dendritic cells and on a subset of CD43RB high lymph node T cells: functional role of thyroid stimulating hormone during immune activation. J Immunol. (2000) 164:6158–65. 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Landucci E, Laurino A, Cinci L, Gencarelli M, Raimondi L. Thyroid hormone, thyroid hormone metabolites and mast cells: a less explored issue. Front Cell Neurosc. (2019) 13:79. 10.3389/fncel.2019.00079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Coutelier JP, Kehrl JH, Bellur SS, Kohn LD, Notkins AL, Prabhakar BS. Binding and functional effects of thyroid stimulating hormone to human immune cells. J Clin Immunol. (1990) 10:204–10. 10.1007/bf00918653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Whetsell M, Bagriacik EU, Seetharamaiah GS, Prabhakar BS, Klein JR. Neuroendocrine-induced synthesis of bone marrow-derived cytokines with inflammatory immunomodulating properties. Cell Immunol. (1999) 15:159–66. 10.1006/cimm.1998.1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Klein JR. The immune system as a regulator of thyroid hormone activity. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). (2006) 231:229–36. 10.1177/153537020623100301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Todd I, Pujol-Borrell R, Hammond LJ, McNally JM, Feldmann M, Bottazzo GF. Enhancement of thyrocyte HLA class II expression by thyroid stimulating hormone. Clin Exp Immunol. (1987) 69:524–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dorshkind K, Horseman ND. The roles of prolactin, growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-I, and thyroid hormones in lymphocyte development and function: insights from genetic models of hormone and hormone receptor deficiency. Endocrine Rev. (2005) 21:292–312. 10.1210/edrv.21.2.0397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Provinciali M, Fabris N. Modulation of lymphoid cell sensitivity to interferon by thyroid hormones. J Endocrinol Invest. (1990) 13:187–91. 10.1007/BF03349536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Provinciali M, Muzzioli M, Di Stefano G, Fabris N. Recovery of spleen cell natural killer activity by thyroid hormone treatment in old mice. Nat Immun Cell Growth Regul. (1991) 10:226–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kmiec Z, Mysliwska J, Rachon D, Kotlarz G, Sworczak K, Mysliwski A. Natural killer activity and thyroid hormone levels in young and elderly persons. Gerontology. (2001) 47:282–8. 10.1159/000052813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lee EK, Sunwoo J. NK cells and thyroid disease. Endocrinol Metab. (2019) 34:132–7. 10.3803/EnM.2019.34.2.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Amino N, Mori H, Iwatani Y, Asari S, Izumiguchi Y. Peripheral K lymphocytes in autoimmune thyroid disease: decrease in Graves' disease and increase in Hashimoto's disease. J Clin End Metab. (1982) 54:587–91. 10.1210/jcem-54-3-587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Iwatani Y, Amino N, Kabutomori O, Mori H, Tamaki H, Motoi S, et al. Decrease of peripheral large granular lymphocytes in Graves' disease. Clin Exp Immunol. (1984) 55:239–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Stein-Streilein J, Zakarija M, Papic M, McKenzie MJ. Hyperthyroxinemic mice have reduced natural killer cell activity. Evidence for a defective trigger mechanism. J Immunol. (1987) 139:2502–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Papic M, Stein-Streilein J, Zakarija M, McKenzie JM, Guffee J, Fletcher MA. Suppression of peripheral blood natural killer cell activity by excess thyroid hormone. J Clin Invest. (1987) 79:404–8. 10.1172/JCI112826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang PW, Luo SF, Huang BY, Lin JD, Huang MJ. Depressed natural killer activity in Graves' disease and during antithyroid medication. Clin Endocrinol. (1988) 28:205–14. 10.111/j.1365-2265.1988.tb03657.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pedersen BK, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Bech K, Perrild H, Klarlund K, Høier-Madsen M. Characterization of the natural killer cell activity in Hashimoto's and Graves' diseases. Allergy. (1989) 44:477–81. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1989.tb04186.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lee MS, Hong WS, Hong SW, Lee JO, Kang TW. Defective response of natural killer activity to thyroxine in Graves' disease. Korean J Intern Med. (1990) 5:93–96. 10.3904/kjim.1990.5.2.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hidaka Y, Amino N, Iwatani Y, Kaneda T, Nasu M, Mitsuda N, et al. Increase in peripheral natural killer cell activity in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. Autoimmunity. (1992) 11:239–46. 10.3109/08916939209035161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Aust G, Lehmann I, Heberling HJ. Different immunophenotype and autoantibody production by peripheral blood and thyroid-derived lymphocytes in patients with Graves' disease. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diab. (1996) 104:50–58. 10.1055/s-0029-1211422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wenzel BE, Chow A, Baur R, Schleusener H, Wall JR. Natural Killer cell activity in patients with Graves' disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Thyroid. (1998) 8:1019–22. 10.1089/thy.1998.8.1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Solerte S, Precerutti S, Gazzaruso C, Locatelli E, Zamboni M, Schifino N, et al. Defect of a subpopulation of natural killer immune cells in Graves' disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis: normalizing effect of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate. Eur J Endocrinol. (2005) 152:703–12. 10.1530/eje.1.01906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zhang Y, Ly G, Lou X, Peng D, Qu X, Yang X, et al. NKG2A expression and impaired function of NK cells in patients with new onset of Graves' disease. Int Immunopharmacol. (2015) 24:133–9. 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mori H, Amino N, Iwatani Y, Asari S, Izumiguchi Y, Kumahara Y, et al. Decrease of immunoglobulin G-Fc receptor-bearing T lymphocytes in Graves' disease. J Clin End Metab. (1982) 55:399–402. 10.1210/jcem-55-3-399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gallagher TF, Hellman L, Finkelstein J, Yoshida K, Weitzman ED, Roffward HD, et al. Hyperthyroidism and cortisol secretion in man. J Clin End Metab. (1972) 34:919–27. 10.1210/jcem-34-6-919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bonnyns M, Cano P, Osterland CK, Mckenzie JM. Immune reactions in patients with Graves' disease. Am J Med. (1978) 65:971–7. 10.1016/002-9343(78)90749-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Johnson E, Kamilaris T, Calogero A, Gold P, Chrousos G. Experimentally-induced hyperthyroidism is associated with activation of the rat hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Eur J Endocrinol. (2005) 153:177–85. 10.1530/eje.1.01923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Yabuhara A, Yang FC, Nakazawa T, Iwasaki Y, Mori T, Koike K. A killing defect of natural killer cells as an underlying immunological abnormality in childhood systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. (1996) 23:171–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Finkelstein JW, Royar RM, Hellman L. Growth hormone secretion in hyperthyroidism. J Clin End Metab. (1974) 38:634–7. 10.1210/jcem-38-4-634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Chopra IJ. Gonadal steroids gonadotropins in hyperthyroidism. Med Clin North Am. (1975) 59:1109–21. 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)31961-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Judge SJ, Murphy WJ, Canter RJ. Characterizing the dysfunctional NK cell: assessing the clinical relevance of exhaustion, anergy, and senescence. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2020) 10:49. 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Marazuela M, Vargas JA, Alvarez-Mon M, Albarran F, Lucas T, Durantez A. Impaired natural killer cell cytotoxicity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in Graves' disease. Eur J Endocrinol. (1995) 132:175–80. 10.1530/eje.0.1320175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Magnusson L, Barcenilla H, Pihl M, Bensing S, Carlsson PO, Casas R, et al. Mass cytometry studies of patients with autoimmune endocrine diseases reveal distinct disease-specific alterations in immune cell subsets. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:288. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Rojano J, Sasián S, Gavilán I, Aguilar M, Escobar L, Girón JA. Serial analysis of the effects of methimazole or radical therapy on circulating CD16/56 subpopulations in Graves' disease. Eur J Endocrinol. (1998) 139:314–16. 10.1530/eje.01390314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.McGregor AM, Petersen MM, McLachlan SM, Rooke P, Smith BR, Hall R. Carbimazole and autoimmune response in Graves' disease. N Engl J Med. (1980) 7:302–7. 10.1056/NEJM198008073030603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ben-Shmuel A, Biber G, Barda-Saad M. Unleashing natural killer cells in the tumor microenvironment-the next generation of immunotherapy? Front Immunol. (2020) 11:275. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Malaer JD, Marrufo AM, Mathew PA. 2B4 (CD244, SLAMF4) and CS1 (CD319, SLAMF7) in systemic lupus erythematosus and cancer. Clin Immunol. (2019) 204:50–6. 10.1016/j.clim.2018.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]