Abstract

A butcher with chronic dermatitis presented with a second episode of Streptococcus suis meningitis, 8 years after the first episode. To distinguish between reinfection and persistent carriage, we compared the two S. suis isolates using whole genome sequencing. We investigated whole genome sequences of the S. suis isolates by means of substitution rates and population structure of closely related strains in addition to available clinical information. Genome‐wide analyses revealed an inserted region consisting of 12 genes in the first isolate and the calculated substitution rate between the isolates suggested infections were caused by highly similar, but unrelated strains. Continuous occupational exposure likely resulted in reinfection with S. suis in a butcher.

Keywords: bacterial meningitis, reinfection, Streptococcus suis, whole genome sequencing

Impacts

We report the first genomic comparison between consecutive Streptococcus suis strains, isolated from a Dutch butcher with recurring meningitis.

We conclude this reinfection was the result of similar yet unrelated strains based on genomic analyses.

Professionals in continuous close contact with pigs should be vigilant of reinfection even after previous S. suis related illness as natural infection may not provide protection against future infections.

1. INTRODUCTION

Streptococcus suis is a Gram‐positive bacterium with zoonotic potential, causing meningitis, septicaemia and arthritis (Wertheim, Nghia, Taylor, & Schultsz, 2009). Streptococcus suis is rarely found in healthy individuals, but is a commensal of pigs and is carried in the upper respiratory and the gastrointestinal tracts of up to 100% of pigs in the Netherlands.

The S. suis serotype is determined by the antigenic properties of the polysaccharide capsule. Serotype 2 is responsible for infections in pigs and causes the majority of zoonotic infections (Goyette‐Desjardins, Auger, Xu, Segura, & Gottschalk, 2014). In the Netherlands, zoonotic infections with S. suis are observed predominantly in persons who have been in close contact with pigs, such as hunters, butchers and farmers (van de Beek, Spanjaard, & Gans, 2008). Despite passive surveillance through the Netherlands Reference Laboratory of Bacterial Meningitis (NRLBM), underreporting of S. suis meningitis cases still occurs (van de Beek et al., 2008; Wertheim et al., 2009). Vaccines that protect against S. suis infection are not available for human use.

We describe a middle‐aged male butcher who was known to suffer from chronic dermatitis and to carry porcine MRSA since 2007. On 19 April 2015, the patient presented with fever, headache, vomiting and diarrhoea. Streptococcus suis was cultured from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The isolate was submitted to the NRLBM, where it was linked to another isolate from CSF from the same patient isolated in 2007. Using whole genome sequencing, we investigated genetic differences between the 2007 isolate, 2071319, and the 2015 isolate, 2150651, potentially explaining this recurrent infection.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The S. suis isolates were sequenced as described previously using paired‐end MiSeq sequencing (Willemse et al., 2016). We performed MLST using (https://pubmlst.org/ssuis) and annotated the genomes using Prokka 1.9 (https://github.com/tseemann/prokka). Roary (Page et al., 2015) was used to calculate core and pangenomes. For substitution rate calculation, SNPs were determined by mapping sequencing reads against the closely related reference genome of P1/7 using SMALT (https://sourceforge.net/projects/smalt), to include SNPs in intergenic regions, which are typically not included in a core genome, in the analysis. SNPs were extracted using Samtools (Li, 2011). Mappings were inspected using Artemis (https://www.sanger.ac.uk/science/tools/artemis). SNPs for phylogenetic analysis were extracted from the core genome alignment of Roary using SNP‐sites (https://github.com/sanger-pathogens/snp-sites). Maximum likelihood trees were generated with RAxML 8.1.6 (https://github.com/stamatak/standard-RAxML) and run until convergence at the bootstopping criterion.

3. RESULTS

Isolate 2071319 (ERS902349) was previously included in a genomic comparison of S. suis isolates from the Netherlands (Willemse et al., 2016) whilst isolate 2150651 (ERS1669548) was sequenced using identical methods. The 2071319 and 2150651 genomes were 2,048,581 and 2,036,490 nucleotides in length, respectively, and both belonged to ST1 and were serotype 2. GC contents were 41.17% and 41.23%, respectively. However, 2071319 contained 1988 coding sequences (CDS) whilst 2150651 contained 1970 CDS. The core genome of the two isolates comprised 1914 genes, leaving 31 genes in the accessory genome of which 24 genes belonged to 2071319 and seven genes to 2150651 (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of accessory genes not shared between isolate 2071318 and 2150651 as determine by the Roary pangenome pipeline

| Isolate | Draft genome gene location | Predicted protein function | Protein length | Nearest BLASTP reference protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2071319 | 220 | Mac family protein | 1,084 | WP_012775646.1 |

| 380 | Competence/damage‐inducible protein A | 272 | WP_012774894.1 | |

| 753 | IS110 family transposase | 242 | CYX90486.1 | |

| 760 | Minor spike protein H | 202 | EQJ03522.1 | |

| 891 | Serine protease | 712 | WP_053866547.1 | |

| 937 | Site‐specific integrase | 436 | WP_011922382.1 | |

| 938 | hypothetical protein | 76 | WP_011922383.1 | |

| 939 | Replication initiator protein | 412 | WP_014636592.1 | |

| 940 | Hypothetical protein | 174 | WP_011922385.1 | |

| 941 | Hypothetical protein | 101 | WP_012775097.1 | |

| 942 | Hypothetical protein | 433 | WP_012775098.1 | |

| 943 | Transcriptional regulator | 68 | WP_012775099.1 | |

| 944 | Membrane/hypothetical protein | 325 | WP_011922387.1 | |

| 945 | Hypothetical protein | 279 | WP_011922388.1 | |

| 946 | Hypothetical protein | 134 | WP_012028114.1 | |

| 947 | Hypothetical protein | 340 | WP_012775100.1 | |

| 948 | Hypothetical protein | 538 | WP_011922392.1 | |

| 1,018 | Hypothetical protein | 108 | WP_012775144.1 | |

| 1,052 | Peptidase C26 | 67 | CYV04131.1 | |

| 1,083 | Penicillinase repressor (89% ID) | 99 | WP_011921706.1 | |

| 1,213 | Cell surface protein (SadP) | 902 | WP_074392131.1 | |

| 1,223 | ABC transporter ATP‐binding protein | 275 | WP_074411925.1 | |

| 1,362 | N‐acetylmuramoyl‐l‐alanine amidase | 373 | WP_074415670.1 | |

| 1578 | RNA helicase | 467 | WP_041179122.1 | |

| 2150651 | 220 | IgM protease (Mac family protein) | 1,141 | WP_011922092.1 |

| 754 | Minor spike protein | 328 | WP_000466547.1 | |

| 908 | Hypothetical protein | 100 | WP_012775088.1 | |

| 1,067 | Transcriptional regulator | 156 | WP_011921706.1 | |

| 1,197 | Cell surface protein (SadP) | 765 | WP_012775427.1 | |

| 1,240 | Oxidoreductase | 66 | WP_044764778.1 | |

| 1896 | IS110 family transposase | 276 | WP_061843547.1 |

Part of the accessory genome of 2071319, spanning genes 937–948, encoded an integrase, replication initiator protein, transcriptional regulator, but mostly hypothetical proteins without predicted domains. The mean GC content of these contiguous genes was 30.6% and lower than the GC content of the whole genome. Among the remaining accessory genes is the sadP gene, encoding the Streptococcal Adhesion Protein (SadP), which had less than the 95% amino acid identity (84.8%) limit as set by Roary due to the presence of two fewer repeats. Mac family proteins also showed <95% identity due to different number of repeats, and the IS110 family transposases showed overlap, but had much lower protein identity. Other proteins did not show similarities.

Mapping of sequencing reads against the closely related reference genome of strain P1/7 yielded 74 SNPs and 24 indels in 2071319 and 100 SNPs and 15 indels in 2150651. There were 35 SNPs and seven indels shared between 2071319 and 2150651 against P1/7 resulting in 104 SNPs and 25 indels between 2071319 and 2150651. We did not identify regions of high SNP density, indicating these SNPs should be attributed to mutations instead of recombination. Using the SNPs, we estimated a required substitution rate of 6.36·10−6 substitutions per site per year (104 SNPs divided by the average genome size of 2071319 and 2150651, divided by 8 years), which is almost tenfold higher compared to the recently calculated substitution rate of 8.58 × 10−7 for related ST7 isolates in China (Du et al., 2017). It is also higher than the rates calculated for S. pneumoniae (1.57·10−6) and S. aureus (3.3·10−6) strains (Croucher et al., 2011).

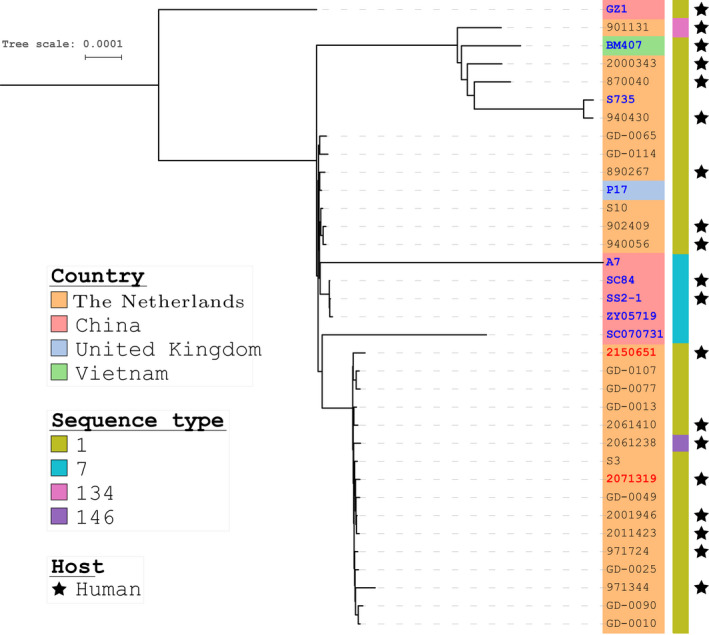

We compared isolates 2071319 and 2150651 with all complete genomes of serotype 2 isolates, belonging to MLST clonal complex 1 (CC1), and included available draft genomes from the Netherlands (Figure 1, Supporting Information Table S1). Single Locus Variants (SLV) of ST1 were included in this analysis because single SNPs in the MLST housekeeping genes may not be representative of variation across the genome. Four main clusters could be observed. Outliers in this tree are GZ1 as well as A7 and SC070731 (both ST7 isolates) with long diverging branches (Supporting Information Figure S1). The cluster consisting of 16 isolates including the isolates 2071319 and 2150651 resulted in a core genome of 1886 genes with an accessory genome of 129 genes, which was slightly smaller than the shared core genome between isolates 2071319 and 2150651. A maximum likelihood tree was again generated to create the highest resolution among the closest related isolates (Supporting Information Figure S2). Whilst isolates 2071319 and 2150651 cluster on the same branch, they cluster amongst other CC1 isolates from the Netherlands suggesting these two isolates are not more related to each other than to the other isolates. Using hierarchical clustering with the presence–absence matrix of the pangenome in R, we compared the accessory genome content of these 16 isolates (Supporting Information Figure S3). Isolates 2071319 and 2150651 clustered among other CC1 isolates from the Netherlands, but two main clusters of the accessory genome were separated in the dendrogram due to the presence or absence of the previously mentioned insertion in 2071319, indicative of co‐evolution of two CC1 subclones circulating in the Netherlands.

Figure 1.

Unrooted maximum likelihood tree demonstrating the phylogenetic structure of core genomes of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 CC1 isolates from the Netherlands and international CC1 reference genomes. Country of isolation is indicated as well as the sequence type of each isolate. Black stars indicate s. suis isolates from human patients. Complete reference genomes are indicated in blue, and isolates 2071319 and 2150651, both responsible for infecting the same patient, are indicated in red. The tree was generated using SNPs in the core genome using RAxML until it converged at the bootstopping criterion, which was at 650 bootstraps [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4. DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that it is unlikely that 2150651 was a descendant from 2071319 and indicate reinfection by two unrelated isolates belonging to different ST1 subclones. The isolates differed by an inserted region, with genes which were likely inserted as a whole, but the origin of this inserted sequence is not well understood. The isolates also had different SadP genes, previously characterized as an adhesin as well as a factor H binding protein which may contribute to zoonotic potential (Ferrando et al., 2017) and is considered a putative virulence factor of S. suis (Kouki et al., 2011; Pian et al., 2012).

Current evidence suggests that carriage of S. suis by humans in general is very rare (Nghia et al, 2011). Whilst potential carriage of S. suis due to continuous professional exposure to pigs (Bonifait, Veillette, Letourneau, Grenier, & Duchaine, 2014), combined with skin lesions related to his chronic dermatitis, cannot be ruled out in this patient, the genomic analysis does not suggest that infections occurred due to long‐term carriage of a single strain as the estimated substitution rate would be too high.

Reinfection with encapsulated bacteria, such as Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae, has been associated with host complement and immunoglobulins deficiencies (Lewis & Ram, 2014). Studies in C3‐ and C5R‐deficient mice indicated an increased susceptibility to S. suis resulting in severe infection in an intranasal mouse model (Seitz et al., 2014). A case of recurrent S. suis infections was reported in a patient after splenectomy (Francois, Gissot, Ploy, & Vignon, 1998). Whilst the patient did not have a medical history suggesting immunodeficiency, he did not consent to additional investigations to confirm or reject S. suis carriage or immunodeficiency, after his recovery.

In conclusion, we identified a patient with a S. suis reinfection on the basis of whole genome sequence analysis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We acknowledge the technicians at the Netherlands Reference Laboratory of Bacterial Meningitis for technical assistance.

Willemse N, van der Ende A, Schultsz C. Reinfection with Streptococcus suis analysed by whole genome sequencing. Zoonoses Public Health. 2019;66:179–183. 10.1111/zph.12528

Funding information

This study was supported by the ANTIGONE consortium funded by the EU 7th Framework Program (EU F7P 278976).

REFERENCES

- Bonifait, L. , Veillette, M. , Letourneau, V. , Grenier, D. , & Duchaine, C. (2014). Detection of Streptococcus suis in bioaerosols of swine confinement buildings. Applied and Environment Microbiology, 80, 3296–3304. 10.1128/AEM.04167-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croucher, N. J. , Harris, S. R. , Fraser, C. , Quail, M. A. , Burton, J. , van der Linden, M. , … Bentley, S. D. (2011). Rapid pneumococcal evolution in response to clinical interventions. Science, 331, 430–434. 10.1126/science.1198545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, P. , Zheng, H. , Zhou, J. , Lan, R. , Ye, C. , Jing, H. , … Xu, J. (2017). Detection of multiple parallel transmission outbreak of Streptococcus suis human infection by use of genome epidemiology, China, 2005. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 23, 204–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando, M. L. , Willemse, N. , Zaccaria, E. , Pannekoek, Y. , van der Ende, A. , & Schultsz, C. (2017). Streptococcal Adhesin P (SadP) contributes to Streptococcus suis adhesion to the human intestinal epithelium. PLoS One, 12, e0175639 10.1371/journal.pone.0175639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois, B. , Gissot, V. , Ploy, M. C. , & Vignon, P. (1998). Recurrent septic shock due to Streptococcus suis . Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 36, 2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyette‐Desjardins, G. , Auger, J. P. , Xu, J. , Segura, M. , & Gottschalk, M. (2014). Streptococcus suis, an important pig pathogen and emerging zoonotic agent‐an update on the worldwide distribution based on serotyping and sequence typing. Emerg Microbes Infect, 3, e45 10.1038/emi.2014.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouki, A. , Haataja, S. , Loimaranta, V. , Pulliainen, A. T. , Nilsson, U. J. , & Finne, J. (2011). Identification of a novel streptococcal adhesin P (SadP) protein recognizing galactosyl‐alpha1‐4‐galactose‐containing glycoconjugates: Convergent evolution of bacterial pathogens to binding of the same host receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 286, 38854–38864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, L. A. , & Ram, S. (2014). Meningococcal disease and the complement system. Virulence, 5, 98–126. 10.4161/viru.26515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. (2011). A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics, 27, 2987–2993. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nghia, H. D. , Tu le, T. P. , Wolbers, M. , Thai, C. Q. , Hoang, N. V. , Nga, T. V. , … Schultsz, C. (2011). Risk factors of Streptococcus suis infection in Vietnam, A case‐control Study. Plos One, 6, e17604 10.1371/journal.pone.0017604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, A. J. , Cummins, C. A. , Hunt, M. , Wong, V. K. , Reuter, S. , Holden, M. T. , … Parkhill, J. (2015). Roary: Rapid large‐scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics, 31, 3691–3693. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pian, Y. , Gan, S. , Wang, S. , Guo, J. , Wang, P. , Zheng, Y. , … Yuan, Y. (2012). Fhb, a novel factor H‐binding surface protein, contributes to the antiphagocytic ability and virulence of Streptococcus suis . Infection and Immunity, 80, 2402–2413. 10.1128/IAI.06294-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz, M. , Beineke, A. , Singpiel, A. , Willenborg, J. , Dutow, P. , Goethe, R. , … Baums, C. G. (2014). Role of capsule and suilysin in mucosal infection of complement‐deficient mice with Streptococcus suis . Infection and Immunity, 82, 2460–2471. 10.1128/IAI.00080-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Beek, D. , Spanjaard, L. , & de Gans, J. (2008). Streptococcus suis meningitis in the Netherlands. J Infection, 57, 158–161. 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertheim, H. F. , Nghia, H. D. , Taylor, W. , & Schultsz, C. (2009). Streptococcus suis: An emerging human pathogen. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 48, 617–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemse, N. , Howell, K. J. , Weinert, L. A. , Heuvelink, A. , Pannekoek, Y. , Wagenaar, J. A. , … Schultsz, C. (2016). An emerging zoonotic clone in the Netherlands provides clues to virulence and zoonotic potential of Streptococcus suis . Scientific Reports, 6, 28984 10.1038/srep28984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials