Summary

Glecaprevir coformulated with pibrentasvir (G/P) is approved to treat hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and was highly efficacious in phase 2 and 3 studies. Treating HCV genotype (GT) 3 infection remains a priority, as these patients are harder to cure and at a greater risk for liver steatosis, fibrosis progression and hepatocellular carcinoma. Data were pooled from five phase 2 or 3 trials that evaluated 8‐, 12‐ and 16‐week G/P in patients with chronic HCV GT3 infection. Patients without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis were either treatment‐naïve or experienced with interferon‐ or sofosbuvir‐based regimens. Safety and sustained virologic response 12 weeks post‐treatment (SVR12) were assessed. The analysis included 693 patients with GT3 infection. SVR12 was achieved by 95% of treatment‐naïve patients without cirrhosis receiving 8‐week (198/208) and 12‐week (280/294) G/P. Treatment‐naïve patients with cirrhosis had a 97% (67/69) SVR12 rate with 12‐week G/P. Treatment‐experienced, noncirrhotic patients had SVR12 rates of 90% (44/49) and 95% (21/22) with 12‐ and 16‐week G/P, respectively; 94% (48/51) of treatment‐experienced patients with cirrhosis treated for 16 weeks achieved SVR12. No serious adverse events (AEs) were attributed to G/P; AEs leading to study drug discontinuation were rare (<1%). G/P was well‐tolerated and efficacious for patients with chronic HCV GT3 infection, regardless of cirrhosis status or prior treatment experience. Eight‐ and 12‐week durations were efficacious for treatment‐naïve patients without cirrhosis and with compensated cirrhosis, respectively; 16‐week G/P was efficacious in patients with prior treatment experience irrespective of cirrhosis status.

Keywords: cirrhosis, G/P, GT3, hepatitis C virus, PWID

Abbreviations

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- AE

adverse event

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- DAA

direct‐acting antiviral

- EASL

European Association of the Liver

- GLE

glecaprevir

- GT

genotype

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- IFN

interferon

- ITT

intention‐to‐treat

- LLOD

lower limit of detection

- LLOQ

lower limit of quantification

- PIB

pibrentasvir

- RBV

ribavirin

- SOF

sofosbuvir

- VEL

velpatasvir

- VOX

voxilaprevir

1. INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype (GT) 3 is the second most prevalent GT worldwide, responsible for approximately 25‐30% of an estimated 71‐80 million HCV infections.1, 2 Direct‐acting antiviral (DAA) therapies have replaced pegylated interferon (pegIFN) plus ribavirin (RBV) as the standard‐of‐care treatment for chronic HCV infection,3 and demonstrate high rates of sustained virologic response at post‐treatment week 12 (SVR12) in most HCV genotypes; however, these rates can be lower in subpopulations of patients with GT3 infection, particularly those with cirrhosis and/or prior HCV therapy.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 In addition to being more difficult to cure, HCV GT3 is associated with higher rates of liver steatosis,10, 11, 12 a higher incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma than other HCV genotypes,13 and is an independent predictor of fibrosis progression.14, 15

Coformulated glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (G/P) is an approved treatment in countries including the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia and Japan, for all six major HCV GTs in patients without cirrhosis and with compensated cirrhosis.16, 17, 18 Glecaprevir (GLE) and pibrentasvir (PIB) each have a high barrier to resistance, potent pangenotypic antiviral activity,19, 20 primarily biliary metabolism and clearance, and negligible renal excretion.21 In vitro, PIB maintains activity against GT3a NS5A single‐position amino acid substitutions known to confer high degrees of resistance to earlier‐generation NS5A inhibitors: M28T, A30K and Y93H, each of which confers less than 2.5‐fold increase to the effective half‐maximal concentration (EC50) of PIB.19

Based on recent figures from the Polaris Observatory, treatment‐naïve patients without cirrhosis are projected to represent approximately 80% of patients with HCV infection, including those with GT3.22 In addition, epidemiological evidence suggests that 50‐65% of people with GT3 infection are current or were former injection drug users,4, 23, 24 a patient population that is implicated in driving emerging trends in the HCV epidemic.25, 26 Currently, G/P is the only 8‐week regimen recommended by both the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the European Association of the Liver (EASL) treatment guidelines for treatment‐naïve GT3‐infected patients without cirrhosis27, 28; this was based on a 95% SVR at post‐treatment week 12 (SVR12) rate in the phase 3 study, ENDURANCE‐3.29

As mentioned above, HCV GT3‐infected patients with concomitant cirrhosis and/or prior HCV treatment experience have historically been the most difficult patients to cure.30, 31, 32 In the phase 3 study SURVEYOR‐2 Part 3, 98% (39/40) of treatment‐naïve patients with HCV GT3 infection and compensated cirrhosis achieved SVR12 after 12 weeks of G/P.33 Based in part on these findings, AASLD and EASL recommend 12 weeks of G/P for treatment‐naïve patients with compensated cirrhosis. In SURVEYOR‐2 Part 3, the SVR12 rates in treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis treated for 12 and 16 weeks were 91% and 95%, respectively; the SVR12 rate in treatment‐experienced patients with compensated cirrhosis treated for 16 weeks was 96%.33 Based in part on these results, 16‐week G/P is an alternative regimen per AASLD guidelines for patients with pegIFN‐based treatment experience, irrespective of the presence of cirrhosis.

In this integrated analysis, data were pooled across five phase 2 or 3 trials that evaluated efficacy and safety of 8, 12 and 16 weeks of G/P in patients with chronic HCV GT3 infection, including those with compensated cirrhosis and/or prior treatment experience. Patients were grouped by cirrhosis status, prior treatment experience and G/P treatment duration. Safety and SVR12 were analysed for each subgroup.

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1. Study oversight

All patients signed informed consent for their respective trial, and the original studies were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization guidelines and the ethics set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. All authors had access to all relevant study data, and reviewed and approved this manuscript for submission.

2.2. Study design

Data were pooled from five clinical trials: SURVEYOR‐2 Parts 1 and 2 (phase 2), SURVEYOR‐2 Part 3 (phase 3) [NCT02243293], and the phase 3 studies ENDURANCE‐3 (NCT02640157), EXPEDITION‐2 (NCT02738138), EXPEDITION‐4 (NCT02651194) and MAGELLAN‐2 (NCT02692703). Patients received once‐daily oral GLE (identified by AbbVie and Enanta Pharmaceuticals; 300 mg) and PIB (120 mg), either as separate tablets (phase 2 studies) or coformulated (phase 3 studies), without ribavirin, for 8, 12 or 16 weeks.

2.3. Patient population

Eligibility criteria were generally the same between studies; Table S1 shows any discrepancies in eligibility criteria between phase 2 and phase 3 studies. Briefly, adults at least 18 years old, with chronic HCV GT3 infection and compensated liver disease, with or without cirrhosis, were enrolled. Patients enrolled in EXPEDITION‐2, MAGELLAN‐2 and EXPEDITION‐4 were coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV‐1), post–liver or post–kidney transplant recipients, or had chronic kidney disease stage 4 or 5, respectively. Coinfection with hepatitis B virus or multiple HCV GTs was exclusionary for all studies. Patients who were HCV treatment‐naïve or treatment‐experienced, defined here as having been treated previously with interferon (IFN) or pegylated IFN (pegIFN) with or without RBV, or sofosbuvir (SOF) plus RBV with or without pegIFN, were included. Ongoing recreational drug use was not exclusionary unless it could preclude protocol adherence, as assessed by the study investigator. Determination of the presence or absence of cirrhosis and fibrosis staging are detailed in the Supporting Information. HCV GT and subtype were determined by the Versant® HCV Genotype Inno LiPA assay, version 2.0. If the LiPA assay was unable to genotype a sample, GT and subtype were determined by a Sanger sequencing assay of a region of the NS5B gene. Genotypes and subtypes were subsequently confirmed via phylogenetic analysis of available NS3/4A and/or NS5A sequences.

2.4. Endpoints

The endpoint of efficacy was described for the following GT3 subpopulations: treatment‐naïve noncirrhotic (8 and 12 weeks G/P), treatment‐naïve cirrhotic (12 weeks G/P), treatment‐experienced noncirrhotic (12 or 16 weeks G/P) and treatment‐experienced cirrhotic (16 weeks G/P). The endpoint of safety was described for the GT3 population overall and for the GT3 subpopulations of without cirrhosis and with cirrhosis, regardless of treatment duration or prior treatment experience.

The primary efficacy assessment was SVR12, defined as having HCV RNA less than the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) at post‐treatment week 12. For patients enrolled and treated in SURVEYOR‐2, sample preparation was done using the High Pure System and plasma HCV RNA levels were determined by a central laboratory using the COBAS TaqMan® real‐time reverse transcriptase‐PCR (RT‐PCR) assay v. 2.0 (Roche Molecular Diagnostics Pleasanton, CA, USA), which has a LLOQ of 25 IU/mL and a lower limit of detection (LLOD) of 15 IU/mL for HCV GT3. For patients enrolled and treated in all other trials included in this analysis, plasma HCV RNA levels were determined by a central laboratory using the COBAS® AmpliPrep/TaqMan HCV Quantitative Test, v2.0 (Roche Molecular Diagnostics), which has an LLOQ and LLOD of 15 IU/mL for all HCV GTs. Efficacy analyses were conducted in the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) population, which included all patients who received at least one dose of study drug. A modified intention‐to‐treat (mITT) analysis was also conducted, in which patients who failed treatment due to reasons unrelated to efficacy such as premature discontinuation, loss to follow‐up, or nonadherence to the study drug (defined below under “Other Assessments”) were excluded from the analysis. Secondary efficacy endpoints were the percentage of patients in the ITT population with on‐treatment virologic failure and post‐treatment relapse.

Adverse events (AEs), vital signs, physical examination, electrocardiogram and laboratory assessments were evaluated in all studies. Treatment‐emergent AEs were collected from the first administration of study drug until 30 days after study drug discontinuation. Relatedness of AEs to DAA administration was determined by the study investigator.

2.5. Other assessments

Treatment adherence was calculated as the percentage of tablets taken (determined by pill counts at study visits from week 4, 8, 12 [where applicable] and 16 [where applicable]) relative to the total expected number of tablets, where adherence needed to be between 80% and 120% at each 4‐week dispensation interval (thus, adherence values below 80% and above 120% were considered nonadherent). For resistance analyses, a polymorphism was defined as a baseline amino acid difference relative to the appropriate subtype‐specific reference sequence. Regions encoding full‐length NS3/4A or NS5A were sequenced by next‐generation sequencing from available baseline samples from all patients. Baseline polymorphisms were identified using a 15% detection threshold at amino acid positions 155, 156 and 168 in NS3 and 24, 28, 30, 31, 58, 92 and 93 in NS5A.

2.6. Statistical analyses

Demographics, baseline characteristics and safety analyses were performed on the ITT population, which included all patients that received at least one dose of study drugs. Efficacy analyses were performed on the ITT and mITT populations. For the primary efficacy endpoint (SVR12), a two‐sided 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated using the normal approximation to the binomial distribution. Subgroup efficacy analyses of SVR12 (including stratification by race, fibrosis score, whether receiving opioid substitution therapy, history of drug use and baseline polymorphisms in NS3 and NS5A) were performed on the mITT population. For the GT3 subpopulation of treatment‐naïve or treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis, the difference in the rate of relapse between treatment durations was calculated with a 95% confidence score interval. For the GT3 subpopulation of treatment‐naïve patients without cirrhosis (8 and 12 weeks), treatment duration was compared within subgroups using Fisher's exact test.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics and demographics

Among 693 patients with HCV GT3 infection, the majority (72%; 502/693) had no prior history of HCV treatment and were without cirrhosis; these patients were treated with either 8 weeks (n = 208) or 12 weeks (n = 294) of G/P (Table 1). Sixty‐nine treatment‐naïve patients with compensated cirrhosis received G/P for 12 weeks. Forty‐nine and 22 treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis were treated with G/P for 12 and 16 weeks, respectively. Fifty‐one treatment‐experienced patients with compensated cirrhosis were treated with G/P for 16 weeks. Patient demographics were largely well‐balanced across patient groups and G/P treatment durations. A substantial proportion of patients across all patient groups had a history of injection drug use (64% overall), which is consistent with epidemiological data of high prevalence of injection drug use in patients with HCV GT3 infection. Smaller subgroups of patients had stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease (n = 12), HIV coinfection (n = 26), or were post–liver or post–kidney transplantation (n = 24). Across all patient groups, 78% of patients had no baseline polymorphisms in NS3 or NS5A. Prevalence of baseline polymorphisms in NS5A ranged from 14 to 29%, with the highest prevalence (29%) occurring in treatment‐naïve patients without cirrhosis treated for 8 weeks.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics

| Characteristic | Treatment‐naïve | Treatment‐experienced | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without cirrhosis | Cirrhosis | Without cirrhosis | Cirrhosis | |||

| 8 weeks N = 208 | 12 weeks N = 294 | 12 weeks N = 69 | 12 weeks N = 49 | 16 weeks N = 22 | 16 weeks N = 51 | |

| Male, n (%) | 123 (59) | 167 (57) | 41 (59) | 32 (65) | 14 (64) | 38 (75) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 180 (87) | 258 (88) | 64 (93) | 42 (86) | 20 (91) | 45 (88) |

| Asian | 14 (7) | 20 (7) | 2 (3) | 7 (14) | 2 (9) | 4 (8) |

| Black or African American | 6 (3) | 4 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Age, median years (range) | 46 (20‐76) | 49 (22‐71) | 56 (35‐70) | 56 (25‐68) | 59 (29‐66) | 59 (47‐70) |

| BMI, median kg/m2 (range) | 25 (18‐44) | 25 (17‐49) | 28 (19‐51) | 26 (19‐42) | 28 (22‐48) | 27 (21‐42) |

| HCV RNA, median log10 IU/mL (range) | 6.1 (1.2‐7.5) | 6.2 (3.4‐7.6) | 6.2 (4.2‐7.2) | 6.5 (5.1‐7.6) | 6.1 (4.7‐7.3) | 6.5 (4.6‐7.2) |

| Prior treatment experience, n (%) | ||||||

| PegIFN/RBV‐based | – | – | – | 41 (84) | 13 (59) | 26 (51) |

| SOF‐based | – | – | – | 8 (16) | 9 (41) | 25 (49) |

| History of injection drug use, n (%) | 141 (68) | 186 (63) | 51 (74) | 25 (51) | 13 (59) | 25 (49) |

| Recenta drug use | 20 (16) | 20 (12) | 0 | 0 | – | 0 |

| Opioid substitution therapy, n (%) | 38 (18) | 46 (16) | 11 (16) | 4 (8) | 0 | 2 (4) |

| HCV GT3 subtype, n (%) | ||||||

| 3a | 206 (99) | 291 (99) | 68 (99) | 48 (98) | 20 (91) | 50 (98) |

| 3b | 2 (1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) |

| 3 g/i | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 69 (100) | 0 | 0 | 51 (100) |

| Baseline fibrosis stage, n (%) | ||||||

| F0‐F2 | 170 (82) | 263 (89) | 0 | 36 (73) | 17 (87) | 0 |

| F3 | 38 (18) | 31 (11) | 1 (1)b | 13 (27) | 5 (23) | 0 |

| F4 | 0 | 0 | 68 (99) | 0 | 0 | 51 (100) |

| CKD Stage 4 or 5, n (%) | 0 | 11 (4) | 1 (2) | 0 | NA | 0 |

| HIV coinfection, n (%) | 22 (11) | 0 | 4 (6) | 0 | NA | 0 |

| Post–liver or post–kidney transplant, n (%) | 0 | 24 (8) | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 |

| Geographic region, n (%) | ||||||

| North America | 71 (34) | 110 (37) | 49 (71) | 21 (43) | 15 (68) | 33 (65) |

| Europe | 99 (48) | 108 (37) | 5 (7) | 6 (12) | 1 (5) | 2 (4) |

| Rest of world | 38 (18) | 76 (26) | 15 (22) | 22 (45) | 6 (27) | 16 (31) |

| Presence of baseline polymorphismsc, n/N (%) | ||||||

| None | 146/206 (71) | 234/289 (81) | 52/68 (76) | 38/49 (78) | 18/21 (86) | 43/51 (84) |

| NS3/4A | 2/206 (1) | 5/289 (2) | 3/68 (4) | 0 | 0 | 1/51 (2) |

| NS5A | 60/206 (29) | 53/289 (18) | 13/68 (19) | 11/49 (22) | 3/21 (14) | 7/51 (14) |

| A30K | 19 (9) | 15 (5) | 1 (1) | 4 (8) | 1 (5) | 0 |

| Y93H | 10 (5) | 14 (5) | 5 (7) | 4 (8) | 0 | 1 (2) |

BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; GT, genotype; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

<12 months prior to screening; recent drug use data were not captured for patients enrolled in SURVEYOR‐2.

Patient was enrolled as cirrhotic by the investigator.

Includes patients with available baseline NS3 or NS5A sequence data; amino acid positions included in the analysis: 155, 156 and 168 in NS3 and 24, 28, 30, 31, 58, 92 and 93 in NS5A.

3.2. Efficacy

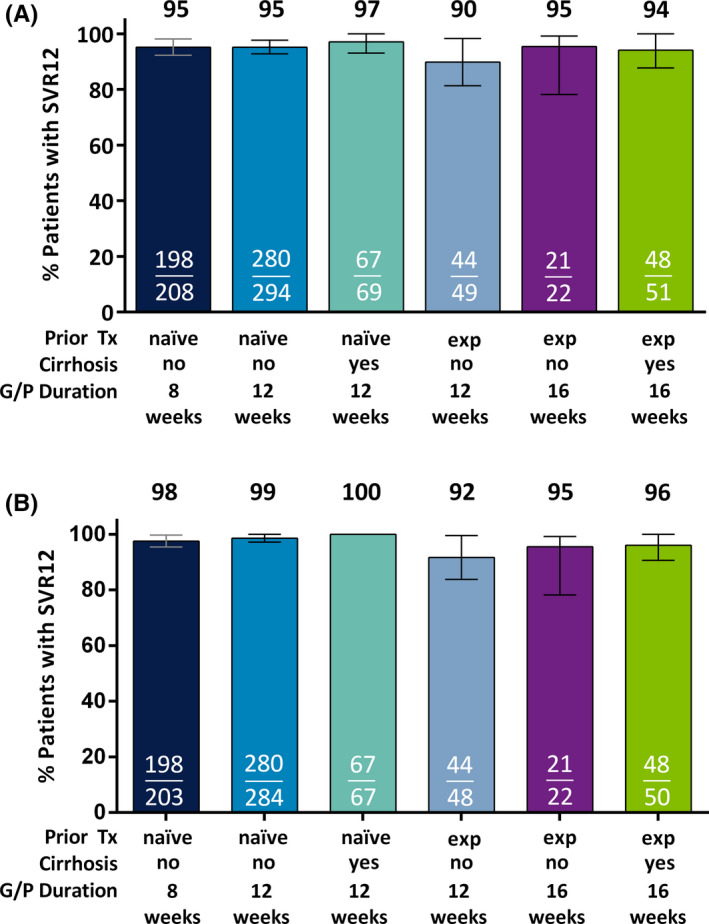

SVR12 (ITT) was achieved by 95% of treatment‐naïve patients without cirrhosis treated with either 8 weeks (198/208; 95% CI 92‐98) or 12 weeks (280/294; 95% CI 93‐98) of G/P (Figure 1A). The rate of post‐treatment relapse was 2.5% (5/200; 95% CI 0.3‐4.7) and 1.4% (4/281; 95% CI 0.04‐2.8) [P = 0.5] in patients treated for 8 and 12 weeks, respectively, and the on‐treatment virologic failure rate was less than 1% regardless of treatment duration (Table 2). Treatment‐naïve patients with compensated cirrhosis treated for 12 weeks had a 97% (67/69; 95% CI 93‐100) SVR12 rate, with 1 virologic failure (an on‐treatment breakthrough). For noncirrhotic patients with prior treatment experience, the SVR12 rate was 90% (44/49; 95% CI 81‐98) and 96% (21/22; 95% CI 87‐100) with 12 and 16 weeks of G/P treatment, respectively. The rate of post‐treatment relapse was 8.3% (4/48; 95% CI 0.5‐16.2) and 4.5% (1/22; 95% CI 0.0‐13.2) [P = 1.0] in patients treated for 12 and 16 weeks, respectively; there was 1 on‐treatment breakthrough for a patient treated for 12 weeks. Treatment‐experienced patients with compensated cirrhosis treated for 16 weeks had an SVR12 rate of 94% (48/51; 95% CI 88‐100), with 2 post‐treatment relapses (2/50; 4.0%) and 1 on‐treatment breakthrough (1/51; 2.0%). Additional details on the patients with virologic failure are presented in Table 4; notably, there were no virologic failures among 17 SOF‐experienced patients without cirrhosis treated for 12 weeks (100% SVR12; 8/8) or 16 weeks (100% SVR12; 9/9); 24/25 (96%) SOF‐experienced patients with cirrhosis treated for 16 weeks achieved SVR12.

Figure 1.

Efficacy of G/P in patients with HCV genotype 3 infection. Patients with HCV genotype 3 were grouped based on prior treatment experience, cirrhosis status and duration of G/P treatment received. Rates of sustained virologic response at post‐treatment week 12 are shown in the (A) intention‐to‐treat (ITT) population, which includes all patients who received at least one dose of study drug, and (B) modified ITT population, which excludes those patients in the ITT population with premature discontinuation, loss to follow‐up or nonadherence to the study drug. For SVR12 rates less than 100%, confidence intervals were calculated at 95% using the normal approximation to the binomial distribution. Tx, treatment; exp, experienced; wks, weeks, SVR12, sustained virologic response at post‐treatment week 12; G/P, glecaprevir and pibrentasvir

Table 2.

Reasons for nonresponse

| Outcome, n (%) | Treatment‐naïve | Treatment‐experienced | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without cirrhosis | Cirrhosis | Without cirrhosis | Cirrhosis | |||

| 8 weeks N = 208 | 12 weeks N = 294 | 12 weeks N = 69 | 12 weeks N = 49 | 16 weeks N = 22 | 16 weeks N = 51 | |

| Virologic failure | ||||||

| On‐treatment failure | 1a (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1a (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | 1a (2) |

| Relapse, n/N (%) | 5/200 (2.5) | 4/281b (1.4) | 0/67 | 4/48b (8.3) | 1/22 (4.5) | 2/50 (4.0) |

| Difference, % (95% CI) | 1.1% (−1.5, 4.4) | – | 3.8% (−14.4, 16.2) | – | ||

| Premature discontinuation | 0 | 4 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing SVR12 data | 4 (2) | 5 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

CI, confidence interval; mITT, modified intention‐to‐treat; SVR12, sustained virologic response at posttreatment week 12.

This patient was nonadherent and was excluded in mITT efficacy analysis.

One of these patients was nonadherent and excluded in mITT efficacy analysis.

Table 4.

Patients with virologic failure: polymorphisms/substitutions in NS3 and NS5A at baseline and time of failure

| Treatment historya | Treatment duration (weeks) | HCV subtype | Cirrhosis Y/N | Reason for nonresponse | NS3 variants | NS5A variants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | At failure | Baseline | At failure | ||||||

| SURVEYOR‐2 | |||||||||

| 1b | Experienced | 12 | 3a | N | Relapse | None | Y56H + Q168R | A30K | A30K + Y93H |

| 2 | Experienced | 12 | 3a | N | Breakthrough | A166S | Y56H + A166S + Q168L | A30K | A30K + Y93H |

| 3 | Experienced | 12 | 3a | N | Relapse | None | None | Y93H | L31F + Y93H |

| 4 | Experienced | 16 | 3a | Y | Relapse | A166S | None | None | M28G |

| 5 | Experienced | 12 | 3a | N | Relapse | None | None | A30K | A30K + Y93H |

| 6 | Experienced | 12 | 3a | N | Relapse | None | None | Y93H | Y93H |

| 7 | Experienced | 16 | 3a | N | Relapse | None | Y56H + Q168R | A30K | A30K + Y93H |

| 8 | Experienceda | 16 | 3a | Y | Relapse | None | None | None | L31F + Y93H |

| 9b | Experienced | 16 | 3a | Y | Breakthrough | A166S | A156G + A166S | None | A30K + Y93H |

| ENDURANCE‐3 | |||||||||

| 10 | Naïve | 12 | 3a | N | Breakthrough | Q168R | Y56H + Q168R | A30V/K, Y93H | A30K + Y93H |

| 11 | Naïve | 12 | 3a | N | Relapse | None | None | None | A30G, Y93H |

| 12b | Naïve | 12 | 3a | N | Relapse | None | Reinfectionc | None | Reinfectionb |

| 13 | Naïve | 12 | 3b | N | Relapse | None | Q80K | V31M | V31M + Y93H |

| 14 | Naïve | 8 | 3a | N | Relapse | T54S | T54S | None | None |

| 15 | Naïve | 8 | 3a | N | Relapse | None | Q168L | A30K | A30K + Y93H |

| 16 | Naïve | 8 | 3a | N | Relapse | A166S | Y56H, Q168L | A30K | A30K + Y93H |

| 17b | Naïve | 8 | 3a | N | Failed to Suppress | A166S, Q168R | Q80R, A156G | A30K | A30K + Y93H |

| 18 | Naïve | 8 | 3a | N | Relapse | A166S | A166S | None | Y93H |

| 19 | Naïve | 8 | 3a | N | Relapse | None | Y56H | A30K | A30K + Y93H |

| MAGELLAN‐2 | |||||||||

| 20 | Naïve | 12 | 3a | N | Relapse | None | Y56H | Y93H | Y93H |

| EXPEDITION‐2 | |||||||||

| 21b | Naïve | 12 | 3a | Y | Breakthrough | None | Y56H | A30V | S24F + M28K |

Detection of baseline polymorphisms and treatment‐emergent substitutions was done with next‐generation sequencing using a 15% detection threshold relative to subtype‐specific reference sequence. For samples with multiple variants (polymorphisms/substitutions) within a target, if individual variants were detected at ≥90% prevalence, they are considered to be linked and denoted by “+”, whereas if one or more of the variants was detected at <90% prevalence, the variants are separated by a comma. Amino acid positions included in the analysis: 36, 43, 54, 55, 56, 80, 155, 156, 166 and 168 in NS3; 24, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 58, 92 and 93 in NS5A.

All patients listed with treatment experience were experienced with pegIFN/RBV, except for patient #8, who was experienced with SOF/RBV.

Nonadherent to DAA and excluded from mITT analysis (as virologic failure unrelated to efficacy); additional details in Table S2.

Patient was infected with a GT3a virus at the time of virologic failure with viral sequences that were distinct from the sequences present at baseline and was determined to have been HCV reinfected.

SVR12 (mITT) was achieved by 98% (198/203; 95% CI 95‐100) and 99% (280/284; 95% CI 97‐100) of treatment‐naïve patients without cirrhosis treated for 8 and 12 weeks, respectively (Figure 1B). Treatment‐naïve patients with compensated cirrhosis (12 weeks of G/P) had a 100% (67/67) mITT SVR12 rate. The mITT SVR12 rates (12 and 16 weeks of G/P) for treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis were 92% (44/48; 95% CI 84‐100) and 96% (21/22; 95% CI 87‐100), while the mITT SVR12 rate for treatment‐experienced patients with compensated cirrhosis (16 weeks of G/P) was 96% (48/50; 95% CI 91‐100). A total of 19 patients were excluded in the mITT analysis for reasons unrelated to efficacy, specifically nonadherence to DAA, early treatment discontinuation and missing SVR12 data (Table S2). Of these, five patients with virologic failure (three with on‐treatment virologic failure and two with relapse) were excluded for nonadherence to study drug.

Using the same mITT analytical approach described above, efficacy in treatment‐naïve patients without cirrhosis was analysed by key patient subgroups, comparing the SVR12 rates between those treated with 8 versus 12 weeks of G/P (Table 3). Across all patient subgroups, there were no statistically significant differences in SVR12 rates analysed by treatment duration, including fibrosis stage, baseline HCV RNA and the presence of baseline NS5A polymorphisms.

Table 3.

Comparison: mITT SVR12 in treatment‐naïve patients without cirrhosis

| Subgroup | 8 weeks | 12 weeks | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVR12, n/N (%) | |||

| Race | |||

| Black | 5/5 (100) | 5/5 (100) | N/A |

| Non‐black | 193/198 (98) | 275/279 (99) | 0.5 |

| HCV RNA | |||

| <800 000 IU/mL | 85/86 (99) | 108/108 (100) | 0.4 |

| ≥800 000 IU/mL | 113/117 (97) | 172/176 (98) | 0.7 |

| Fibrosis stage | |||

| F0‐F2 | 165/168 (98) | 250/254 (98) | 1 |

| F3 | 33/35 (94) | 30/30 (100) | 0.5 |

| History of injection drug use | |||

| Yes | 133/136 (98) | 174/178 (98) | 1 |

| No | 65/67 (97) | 106/106 (100) | 0.1 |

| Recenta injection drug use | |||

| Yes | 18/18 (100) | 16/17 (94) | 0.5 |

| No | 98/101 (97) | 140/143 (98) | 0.7 |

| Opioid substitution therapy | |||

| Yes | 37/37 (100) | 41/42 (98) | 1 |

| No | 161/166 (97) | 239/242 (99) | 0.3 |

| Baseline NS5A polymorphism(s)b | |||

| Yes | 56/59 (95) | 49/52 (94) | 1 |

| No | 140/142 (99) | 226/227 (99) | 0.6 |

| Baseline A30K | |||

| Yes | 15/18 (83) | 13/14 (93) | 0.6 |

| No | 181/183 (99) | 263/266 (99) | 1 |

| Baseline Y93H | |||

| Yes | 10/10 (100) | 12/14 (86) | 0.5 |

| No | 186/191 (97) | 264/266 (99) | 0.1 |

mITT, modified intention‐to‐treat; SVR12, sustained virologic response at posttreatment week 12.

<12 months prior to screening; recent drug use data were not captured for patients enrolled in SURVEYOR‐2.

Includes patients with available baseline NS5A sequence data; amino acid positions included in the analysis: 24, 28, 30, 31, 58, 92, 93 in NS5A.

P value was calculated by Fisher's exact test.

3.3. Resistance

Baseline polymorphisms in NS3 at amino acid positions of interest were rare, and those in NS5A were variably detected (14% to 29%) across the different GT3 cohorts. The baseline prevalence of NS5A‐Y93H and NS5A‐A30K in treatment‐naïve patients without cirrhosis treated for 8 weeks was 5% and 9%, respectively (Table 1). Among treatment‐naive patients without cirrhosis with baseline A30K or Y93H, there were no statistically significant differences in SVR12 rates between the 8‐ and 12‐week durations (Table 3); the mITT SVR12 rates for patients with baseline Y93H treated for 8 and 12 weeks was 100% (10/10; 95% CI 100.0‐100.0) and 86% (12/14; 95% CI 67.4‐100.0), respectively, while the mITT SVR12 rates for patients with baseline A30K treated for 8 and 12 weeks was 83% (15/18; 95% CI 66.1‐100.0) and 93% (13/14; 95% CI 79.4‐100.0), respectively. Of the nine treatment‐experienced patients with virologic failure, five were in the 12‐week arm and had either NS5A‐A30K or Y93H at baseline (Table 4). Overall, in treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis treated for 12 weeks, the baseline prevalence of NS5A‐A30K and NS5A‐Y93H was 8% each; the baseline prevalence of NS5A‐A30K and NS5A‐Y93H in treatment‐experienced patients treated for 16 weeks was 5% and 0% (in those without cirrhosis) and 0% and 2% (in those with cirrhosis), respectively (Table 1). Treatment‐emergent NS3 substitutions Y56H, Q80K/R, A156G or Q168L/R were observed in 12 of the patients with virologic failure (Table 4). Treatment‐emergent NS5A substitutions S24F, M28G/K, A30G/K, L31F or Y93H were detected in 15 patients; the most common substitutions were the linked A30K + Y93H substitutions in NS5A detected in 10 patients at the time of failure (Table 4).

3.4. Adverse events and laboratory abnormalities

Across all patients, adverse events (AEs) occurring in ≥10% of patients were headache, fatigue and nausea (Table 5). Rates of study drug discontinuation due to AEs (0.4%) were low. Serious AEs occurred in 3% of patients, none of which were considered related to study drugs by investigators. Across all patients, grade 3 or higher laboratory abnormalities in alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin or haemoglobin occurred in <1% of patients. There were two patients with grade 3 elevations in ALT and neither was associated with concomitant elevation in total bilirubin; these ALT elevations were not consistent with drug‐induced liver injury. Four patients had grade 3 elevations in total bilirubin; these elevations had indirect predominance and occurred in patients with elevated bilirubin at baseline. The AE and laboratory abnormality profiles were similar between those with and without cirrhosis.

Table 5.

Adverse events and laboratory abnormalities by cirrhosis status

| No cirrhosis N = 573 | Cirrhosis N = 120 | Total N = 693 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event, n (%) | |||

| Any AE | 412 (72) | 95 (79) | 507 (73) |

| Serious AE | 16 (3) | 6 (5) | 22 (3) |

| Serious AE related to study drugsa | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AE leading to study drug discontinuation | 3 (1) | 0 | 3 (<1) |

| AE occurring in ≥10% of total patients | |||

| Headache | 131 (23) | 21 (18) | 152 (22) |

| Fatigue | 102 (18) | 24 (20) | 126 (18) |

| Nausea | 68 (12) | 13 (11) | 81 (12) |

| Deaths | 1 (<1)b | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Laboratory abnormalitiesc, n (%) | |||

| Alanine aminotransferase | |||

| Grade 2 (>3‐5 × ULN) | 2 (<1) | 2 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Grade ≥3 (>5 × ULN) | 2 (<1) | 0 | 2 (<1) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | |||

| Grade ≥3 (>5 × ULN) | 2 (<1) | 0 | 2 (<1) |

| Total bilirubin | |||

| Grade ≥3 (>5 × ULN) | 2 (<1) | 2 (2) | 4 (1) |

AE, adverse event.

ALT must have been post nadir increase in grade.

Relation to study drugs as assessed by investigator.

Accidental overdose in the post‐treatment period, unrelated to study drug.

No grade 4 laboratory abnormalities were observed.

4. DISCUSSION

Patients with HCV GT3 are one of the more difficult‐to‐treat subpopulations of patients with chronic HCV infection. Moreover, epidemiological evidence suggests that a majority of people with GT3 infection are or were injection drug users.4, 23, 24 The majority of injection drug users with HCV GT3 infection do not have cirrhosis and have never been treated for HCV infection; as a result, strategies to ensure access to effective HCV regimens for this population remain a priority.25, 26 In this integrated analysis, we pooled data from 693 patients across five phase 2 or 3 trials that evaluated efficacy and safety of 8, 12 and 16 weeks of G/P in patients with chronic HCV GT3 infection, including those with compensated cirrhosis and/or prior treatment experience with IFN/pegIFN with or without RBV, or SOF plus RBV with or without pegIFN. High SVR12 rates were achieved among all GT3 subpopulations (treatment‐naïve or experienced patients with or without cirrhosis). Importantly, SVR12 rates were ≥95% in treatment‐naïve GT3 patients without cirrhosis who received G/P for 8 weeks as recommended by both the US and EU labels and treatment guidelines, supporting the indication that there is no benefit in extending treatment beyond 8 weeks in this population. There were no virologic failures in treatment‐naive GT3 patients with compensated cirrhosis who received 12‐week G/P. G/P treatment was well‐tolerated, irrespective of cirrhosis status, with low rates of serious AEs and AEs leading to study drug discontinuation. These pooled results highlight that G/P is a highly efficacious regimen with a favourable safety profile, with treatment options for a diverse and wide spectrum of patients with chronic HCV GT3 infection.

According to recent data from the Polaris Observatory, the majority of patients with chronic HCV infection are treatment‐naïve and without cirrhosis22; in this analysis, patients without cirrhosis and with no prior HCV therapy comprised 72% (502/693) of the GT3 population. This large sample size (n = 502) of GT3‐infected patients allowed a more rigorous analysis to compare the efficacy of 8 vs 12 weeks of G/P in treatment‐naïve patients without cirrhosis, and determine whether any baseline patient characteristics negatively impacted SVR12. Overall, there were no statistically significant differences in SVR12 rates when treating for 12 weeks compared to 8 weeks, demonstrating that increasing treatment duration from 8 to 12 weeks is not required for optimal efficacy in this subpopulation. In addition, regardless of treatment duration, no baseline patient or viral characteristic was identified as a negative predictor of response, including fibrosis stage, viral load and NS5A polymorphisms (e.g, A30K or Y93H). Given the relatively small number of patients with baseline A30K in the 8‐week (n = 19; 9%) and 12‐week (n = 15; 5%) treatment arms, the current analysis had limited power to detect a significant difference in SVR12 (mITT); thus, the impact of baseline A30K on efficacy of 8‐week G/P was difficult to assess. These results support current HCV treatment guidelines, which recommend 8‐week G/P treatment without the need for baseline resistance testing in treatment‐naïve, noncirrhotic patients,27, 28 and suggest that G/P is highly effective regardless of past or ongoing injection drug use, or whether a patient is receiving opioid substitution therapy. These findings could be particularly important for patients who inject drugs, as it has been suggested that reduced treatment duration can improve both treatment access and adherence.34 Indeed, as increasingly safe and effective DAA‐based therapies become available to patients, nonadherence can be expected to emerge as the most important risk factor for treatment failure.35 Alleviating the need for adherence to a long duration of treatment could help reduce the strain placed on both patient and provider resources and facilitate increased rates of cure in a population whose successful treatment is critical to reducing or eliminating global HCV burden.36

In the five clinical trials included in this integrated analysis, GT3‐infected patients with prior treatment experience were treated with G/P for either 12 weeks (without cirrhosis only) or 16 weeks (with or without cirrhosis). In this pooled analysis, the SVR12 rate for treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis treated for 16 weeks was higher (96% SVR12 [21/22]; 4.5% relapse rate) than those treated for 12 weeks (90% SVR12 [44/49]; 8.3% relapse rate). The higher relapse rate observed in treatment‐experienced noncirrhotic patients treated for 12 weeks suggests that the longer 16‐week treatment duration may help to minimize relapses in this more difficult‐to‐cure subpopulation. Sixteen weeks of G/P also resulted in similarly high SVR12 rates (96%, mITT) for treatment‐experienced patients with compensated cirrhosis. Overall, these data demonstrate that 16‐week G/P provides high efficacy for treatment‐experienced patients both with and without cirrhosis, and support the US FDA and EU EMA label‐recommended duration of 16 weeks of G/P treatment for patients with HCV GT3 infection and prior treatment experience with IFN/pegIFN with or without RBV, or SOF plus RBV with or without pegIFN.16, 17 Notably, of the 122 total treatment‐experienced patients included in this analysis, 34% (N = 42) had prior experience with SOF; 98% (41/42) of SOF‐experienced patients with GT3 infection treated with G/P achieved SVR12.

Other approved regimens for HCV GT3 infection include sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (SOF/VEL) and SOF/VEL/voxilaprevir (SOF/VEL/VOX). In addition to 8‐week G/P, 12‐weeks of SOF/VEL is also recommended by both EASL and AASLD guidelines for treatment‐naïve GT3‐infected patients without cirrhosis;27, 28 this was based on results of the ASTRAL‐3 and POLARIS‐2 studies in which 12‐week treatment with SOF/VEL yielded SVR rates of 98% (160/163) in treatment‐naïve GT3‐infected patients without cirrhosis and 97% (86/98) in treatment‐naïve or interferon‐experienced GT3‐infected patients without cirrhosis, respectively. AASLD also recommends 12‐week SOF/VEL for treatment‐naïve patients with cirrhosis; however, co‐administration of weight‐based RBV is recommended if baseline resistance testing for Y93H in NS5A is positive.28 Current EASL guidelines recommend SOF/VEL/VOX (12 weeks), but not SOF/VEL, for treatment‐naïve or ‐experienced (IFN‐ or SOF‐based) GT3‐infected patients with compensated cirrhosis. These recommendations are based on the results of the ASTRAL‐3 and ASTRAL‐5 studies, which demonstrated lower SVR rates with SOF/VEL (90‐92%, including a 88% and 97% rate in patients with and without baseline NS5A RASs, respectively, in ASTRAL‐3)32, 37 than the 96% SVR rate reported with SOF/VEL/VOX in the POLARIS‐3 study in treatment‐naïve or treatment‐experienced (IFN‐based) patients with compensated cirrhosis.38 Moreover, in the POLARIS‐4 study, SOF/VEL/VOX also achieved a 96% SVR rate in 52/54 noncirrhotic and cirrhotic GT3‐infected patients with previous DAA experience (excluding NS5A inhibitors).39 Lastly, AASLD recommends 12‐week SOF/VEL and 12‐week SOF/VEL/VOX for treatment‐experienced (IFN‐based for SOF/VEL; IFN‐ or SOF‐based for SOF/VEL/VOX) patients without cirrhosis and with compensated cirrhosis, respectively.27, 28 Notably, while AASLD treatment guidelines for G/P in treatment‐experienced (IFN‐based) GT3‐infected patients are consistent with label recommendations (16 weeks regardless of cirrhosis status), EASL treatment guidelines recommend 12 and 16 weeks of G/P for treatment‐experienced (IFN‐ or SOF‐based) GT3‐infected patients without cirrhosis and with compensated cirrhosis, respectively.

The primary limitation of this integrated analysis is its post hoc nature, which also accounts for the marginally different eligibility criteria (the integrated analysis included patients from both phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials). In addition, the lower sample size of patients in some subgroups (such as treatment‐experienced noncirrhotics) did not allow for formal powered statistical efficacy comparisons between treatment durations. Lastly, there were a low number of patients with NS5A A30K or Y93H baseline polymorphisms, particularly for treatment‐experienced patients treated with 16 weeks of G/P (N = 1 each), which precluded the analysis of impact of these polymorphisms on the 16‐week treatment outcome; however, this was not unexpected since the study population excluded patients with prior NS5A inhibitor treatment experience, and prevalence of these polymorphisms in patients who were never exposed to NS5A inhibitors is low. Moreover, the overall prevalence for A30K and Y93H in this study (6% and 5%, respectively) was consistent with the low prevalence of these polymorphisms in patients with HCV GT3 infection reported in previous studies (4.5‐6% for A30K and 8.3‐8.8% for Y93H).31, 40, 41

In conclusion, SVR12 rates were high (≥95%) for patients with HCV GT3 infection treated with the label‐recommended durations of G/P, and G/P was well tolerated in patients with or without cirrhosis. In treatment‐naïve patients without cirrhosis, efficacy was high with 8 weeks of G/P treatment, and no patient or viral characteristic was associated with lower SVR12; importantly, extending the duration of treatment to 12 weeks did not provide any additional benefit to efficacy. The regimen of G/P for 16 weeks achieved high efficacy in treatment‐experienced patients with or without cirrhosis, with the 12‐week duration in treatment‐experienced patients without cirrhosis being associated with a higher rate of relapse. The data from this integrated analysis support the label‐recommended durations of 8 and 12 weeks of G/P for treatment‐naïve patients without and with cirrhosis, respectively, and 16 weeks of G/P for treatment‐experienced patients, regardless of cirrhosis status.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

AbbVie sponsored the studies (NCT02243293, NCT02640157, NCT02738138, NCT02651194 and NCT02692703), contributed to their design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data and participated in the writing, review and approval of the content of the manuscript. All authors had access to all relevant data. This manuscript contains information on the investigational use of glecaprevir (GLE; formerly ABT‐493) and pibrentasvir (PIB; formerly ABT‐530). S Flamm: Speaker/Consultant: AbbVie, Gilead and Merck; Grant/Research Support: AbbVie and Gilead. D Mutimer: Consultant: AbbVie, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen and Merck. J Rockstroh: Grant/Research support: Gilead; Consultant: Abbott, AbbVie, Bionor, Cipla, Gilead, Janssen, Merck and ViiV; Speaker: Gilead, Janssen and Merck. Y Horsmans: Consultant: AbbVie, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen and Merck. PY Kwo: Grant/Research Support/Advisor: AbbVie, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen and Merck. O Weiland: Advisor/speaker: Merck, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Janssen, Gilead, AbbVie, Medivir. E Villa: Consultant: MSD, AbbVie, Gilead, Bristol‐Myers Squibb and Novartis. J Heo: Grant/Research Support: GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol‐Myers Squibb and Hoffmann‐La Roche; Advisor: AbbVie, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Gilead, Pharma Essentia, SillaJen and Johnson & Johnson. E Gane: Advisor: AbbVie, Gilead, Achillion, Novartis, Roche, Merck and Janssen. S Ryder: Consultant: AbbVie, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, MSD, Conatus and Gilead. TM Welzel: Consultant/Speaker for: Abbvie, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Intercept. P Ruane: Grant/Research Support: AbbVie, Bristol‐Meyers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Idenix, ViiV, Janssen; Consultant/Advisor: AbbVie, Merck, Gilead; Speaker: Gilead, ViiV, Merck; Stockholder: Gilead. K Agarwal: Consultant/Advisor: Janssen, Merck, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Gilead, AbbVie, Astellas, Achillion and Novartis. D Wyles: Grant/Research support: AbbVie, Gilead, Merck; Consultant/Advisor: AbbVie, Gilead, Merck. A Asatryan, S Wang, TI Ng, Z Xue, SS Lovell, P Krishnan, S Kopecky‐Bromberg, R Trinh and F Mensa: employees of AbbVie and may hold stock or stock options.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

AbbVie and the authors would like to express their gratitude to all the patients who participated in the included studies, and their families. They would also like to thank all of the participating study investigators and coordinators. Medical writing was funded by AbbVie and provided by Zoë Hunter, PhD and Ryan J Bourgo, PhD, of AbbVie.

Flamm S, Mutimer D, Asatryan A, et al. Glecaprevir/Pibrentasvir in patients with chronic HCV genotype 3 infection: An integrated phase 2/3 analysis. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26:337–349. 10.1111/jvh.13038

REFERENCES

- 1. Blach S, Zeuzem S, Manns M, et al. Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(3):161‐176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gower E, Estes C, Blach S, Razavi‐Shearer K, Razavi H. Global epidemiology and genotype distribution of the hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2014;61:S45‐S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Asselah T, Thompson AJ, Flisiak R, et al. A predictive model for selecting patients with HCV genotype 3 chronic infection with a high probability of sustained virological response to peginterferon Alfa‐2a/Ribavirin. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0150569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ampuero J, Romero‐Gomez M, Reddy KR. Review article: HCV genotype 3 – the new treatment challenge. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:686‐698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grebely J, Haire B, Taylor LE, et al. Excluding people who use drugs or alcohol from access to hepatitis C treatments – is this fair, given the available data? J Hepatol. 2015;63:779‐782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jacobson IM, Gordon SC, Kowdley KV, et al. Sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 in patients without treatment options. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1867‐1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lawitz E, Freilich B, Link J, et al. A phase 1, randomized, dose‐ranging study of GS‐5816, a once‐daily NS5A inhibitor, in patients with genotype 1‐4 hepatitis C virus. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22:1011‐1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1878‐1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zeuzem S, Dusheiko GM, Salupere R, et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin in HCV genotypes 2 and 3. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1993‐2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fartoux L, Poujol‐Robert A, Guechot J, Wendum D, Poupon R, Serfaty L. Insulin resistance is a cause of steatosis and fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 2005;54:1003‐1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Adinolfi LE, Gambardella M, Andreana A, Tripodi MF, Utili R, Ruggiero G. Steatosis accelerates the progression of liver damage of chronic hepatitis C patients and correlates with specific HCV genotype and visceral obesity. Hepatology. 2001;33:1358‐1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leandro G, Mangia A, Hui J, et al. Relationship between steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C: a meta‐analysis of individual patient data. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1636‐1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nkontchou G, Ziol M, Aout M, et al. HCV genotype 3 is associated with a higher hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in patients with ongoing viral C cirrhosis. J Viral Hepatitis. 2011;18:e516‐e522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bochud PY, Cai T, Overbeck K, et al. Genotype 3 is associated with accelerated fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2009;51:655‐666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Nicola S, Aghemo A, Rumi MG, Colombo M. HCV genotype 3: an independent predictor of fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2009;51:964‐966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. MAVYRET (Glecaprevir and Pibrentasvir Tablets) [US package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. MAVIRET (Glecaprevir and Pibrentasvir Tablets) [SmPC]. Maidenhead, UK: AbbVie; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18. MAVIRET (Glecaprevir and Pibrentasvir Tablets) [package insert]. Tokyo, Japan: AbbVie GK; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ng T, Krishnan P, Pilot‐Matias T, et al. In vitro antiviral activity and resistance profile of the next generation hepatitis C virus NS5A inhibitor pibrentasvir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e02558‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ng TI, Tripathi R, Reisch T, et al. In vitro antiviral activity and resistance profile of the next‐generation hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease inhibitor glecaprevir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e01620‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kosloski MP, Dutta S, Wang H, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of next generation direct‐acting antivirals ABT‐493 and ABT‐530 in subjects with hepatic impairment. J Hepatol. 2016;64(2):S405. Abstract THU‐230. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Polaris Observatory HCVC. Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:161‐176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gigi E, Sinakos E, Lalla T, Vrettou E, Orphanou E, Raptopoulou M. Treatment of intravenous drug users with chronic hepatitis C: treatment response, compliance and side effects. Hippokratia. 2007;11:196‐198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harder J, Walter E, Riecken B, Ihling C, Bauer TM. Hepatitis C virus infection in intravenous drug users. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:768‐770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith DJ, Combellick J, Jordan AE, Hagan H. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) disease progression in people who inject drugs (PWID): a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:911‐921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thomas DL, Astemborski J, Rai RM, et al. The natural history of hepatitis C virus infection: host, viral, and environmental factors. JAMA. 2000;284:450‐456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. European Association for the Study of the Liver . EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C 2018. J Hepatol. 2018;69:461‐511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. AASLD‐IDSA Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C virus. 2017. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed July 16, 2017.

- 29. Zeuzem S, Foster GR, Wang S, et al. Glecaprevir‐pibrentasvir for 8 or 12 weeks in HCV genotype 1 or 3 infection. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:354‐369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nelson DR, Cooper JN, Lalezari JP, et al. All‐oral 12‐week treatment with daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection: ALLY‐3 phase III study. Hepatology. 2015;61:1127‐1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leroy V, Angus P, Bronowicki JP, et al. Daclatasvir, sofosbuvir, and ribavirin for hepatitis C virus genotype 3 and advanced liver disease: a randomized phase III study (ALLY‐3 + ). Hepatology. 2016;63:1430‐1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Foster GR, Afdhal N, Roberts SK, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 2 and 3 infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2608‐2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wyles D, Poordad F, Wang S, et al. Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir for HCV genotype 3 patients with cirrhosis and/or prior treatment experience: a partially randomized phase III clinical trial. Hepatology. 2018;67(2):514‐523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Grebely J, Oser M, Taylor LE, Dore GJ. Breaking down the barriers to hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment among individuals with HCV/HIV coinfection: action required at the system, provider, and patient levels. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(Suppl 1):S19‐S25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Soriano V, Fernandez‐Montero JV, de Mendoza C, et al. Treatment of hepatitis C with new fixed dose combinations. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18:1235‐1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bajis S, Dore GJ, Hajarizadeh B, Cunningham EB, Maher L, Grebely J. Interventions to enhance testing, linkage to care and treatment uptake for hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;47:34‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wyles DL, Bräu N, Kottilil S, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for the treatment of HCV in patients coinfected with HIV‐1: an open‐label, phase 3 study. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(1):6‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jacobson IM, Lawitz E, Gane EJ, et al. Efficacy of 8 weeks of sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir in patients with chronic HCV infection: 2 phase 3 randomized trials. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):113‐122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bourliere M, Gordon SC, Flamm SL, et al. Sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir for previously treated HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2134‐2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hernandez D, Zhou N, Ueland J, Monikowski A, McPhee F. Natural prevalence of NS5A polymorphisms in subjects infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 and their effects on the antiviral activity of NS5A inhibitors. J Clin Virol. 2013;57:13‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Walker A, Siemann H, Groten S, Ross RS, Scherbaum N, Timm J. Natural prevalence of resistance‐associated variants in hepatitis C virus NS5A in genotype 3a‐infected people who inject drugs in Germany. J Clin Virol. 2015;70:43‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials