Abstract

Context

While prior research has examined how primary care providers (PCPs) can care for breast and colon cancer survivors, little is known about their role in thyroid cancer survivorship.

Objective

To understand PCP involvement and confidence in thyroid cancer survivorship care.

Design/Setting/Participants

We surveyed PCPs identified by thyroid cancer patients from the Georgia and LA SEER registries (n = 162, response rate 56%). PCPs reported their involvement in long-term surveillance and confidence in handling survivorship care (role of random thyroglobulin levels and neck ultrasound, and when to end long-term surveillance and refer back to the specialist). We examined: 1) PCP-reported factors associated with involvement using multivariable analyses; and 2) bivariate associations between involvement and confidence in handling survivorship care.

Main Outcome Measures

PCP involvement (involved vs not involved) and confidence (high vs low).

Results

Many PCPs (76%) reported being involved in long-term surveillance. Involvement was greater among PCPs who noted clinical guidelines as the most influential source in guiding treatment (OR 4.29; 95% CI, 1.56-11.82). PCPs reporting high confidence in handling survivorship varied by aspects of care: refer patient to specialist (39%), role of neck ultrasound (36%) and random thyroglobulin levels (27%), and end long-term surveillance (14%). PCPs reporting involvement were more likely to report high confidence in discussing the role of random thyroglobulin levels (33.3% vs 7.9% not involved; P < 0.01).

Conclusions

While PCPs reported being involved in long-term surveillance, gaps remain in their confidence in handling survivorship care. Thyroid cancer survivorship guidelines that delineate PCP roles present one opportunity to increase confidence about their participation.

Keywords: thyroid neoplasms, survivorship, primary health care

The number of patients newly diagnosed with thyroid cancer has increased more than 3-fold in the past 50 years, with an estimated 52 890 new cases of thyroid cancer expected to be diagnosed in 2020 1-3). With 5-year survival rates nearing 100%, this represents a growing population of survivors who need long-term monitoring and surveillance (2, 4). Most often, these patients are followed by their treating cancer specialist (eg, endocrinologist), who provides the necessary follow-up survivorship care. However, workforce shortages of endocrinologists, combined with people living longer with cancer, brings into question the sustainability of this model (5). One potential solution includes involving primary care providers (PCPs). As national organizations have called for team-based care delivery for cancer survivors, an approach that incorporates the patient’s risk of recurrence and long-term and late effects, has been recommended (6-9). The majority of thyroid cancer patients are diagnosed with differentiated thyroid cancer, where the risk of recurrence is low and risk of experiencing long-term and late effects is minimal (10). After initial management by endocrinologists, PCPs may be well-suited to provide follow-up cancer care for select groups of lower-risk patients.

Prior research has largely focused on PCP involvement in the care of breast and colon cancer survivors and highlights several difficulties in the implementation of team-based care. Providers, for example, differ in their preferences for who should handle survivorship care. In a survey of medical oncologists and PCPs, while a sizable proportion of PCPs (51%) supported a PCP or shared care model, the majority of cancer specialists (59%) preferred an oncologist-led model (11). Additionally, PCPs often endorse lacking confidence and knowledge to provide survivorship care (12). When PCPs were surveyed about caring for cancer survivors, nearly half noted feeling unprepared to evaluate (47.9%) and manage (49.8%) long-term effects (13). Potosky and colleagues reported that, when caring for breast cancer survivors, about 40% of PCPs disagreed with the statement that “PCPs have skills necessary to provide follow-up care related to the effects of cancer or its treatment” (14).

Whether these findings are similar for PCPs caring for thyroid cancer survivors is not known. Understanding PCP involvement and confidence in handling aspects of survivorship care is a critical first step to determine prior to expanding PCP roles in thyroid cancer survivorship care delivery. Therefore, by leveraging a sample of PCPs who provide care to a population-based cohort of thyroid cancer patients, we aimed to describe PCP involvement in thyroid cancer long-term surveillance, and their confidence in handling various aspects of thyroid cancer survivorship care.

Materials and Methods

Study population

To identify our sample of PCPs, we first surveyed patients diagnosed with differentiated thyroid cancer from 2014 to 2015. Patients were identified from the Georgia and Los Angeles Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registries, which have a diverse cohort of patients. In the survey, patients were asked to identify an “other doctor most involved in your thyroid cancer treatment decision making (other than your surgeon or endocrinologist).” Between August 2018 and August 2019, all identified PCPs were surveyed from Los Angeles and in parallel, a similar number were surveyed from Georgia (N = 289). To improve response rates, we used a modified Dillman method, consisting of an initial mailing of the packet including a cover letter and the survey, providing $50 cash incentive in the initial mailing, follow-up phone calls to nonresponders, and additional mailings to nonresponders (15). PCPs were excluded if they were deceased prior to the first mailing, reported being retired, could not be located, or did not meet study screening criteria after the initial contact was made (N = 15). Our analysis therefore includes 162 PCPs (response rate, 56%).

The study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Michigan, University of Southern California, Emory University, the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, the California Cancer Registry, and the Georgia Department of Public Health.

Measures

Survey content was developed on the basis of a conceptual framework, research questions and hypotheses, systematic review of literature, and our prior work (16-20). To assess content validity, we used standard techniques, including reviews by design and content experts and pilot testing with PCPs at the University of Michigan.

PCP involvement in long-term surveillance

To determine PCP involvement in long-term surveillance, respondents were asked: “After patients are finished with their primary treatment for thyroid cancer and their treating physician thinks there is no sign of residual disease, how often are you involved in the long-term surveillance for progression or recurrence?” Response options were on a 5-point Likert-type scale from “never” to “almost always.” We dichotomized results into not involved (“never,” “rarely”) versus involved (“sometimes,” “often,” “almost always”).

We chose this cutoff because of our clinical interest in understanding any PCP involvement in long-term surveillance, and to be consistent with our prior work on PCP involvement in the management of other cancers (17).

PCP confidence in handling thyroid cancer survivorship care

Respondents were asked to report how confident they were discussing several key aspects of follow-up care for thyroid cancer survivors, including the role of random thyroglobulin levels in long-term surveillance, role of neck ultrasound in long-term surveillance, when to end long-term surveillance, and when to refer back to the specialist (eg, endocrinologist or surgeon). Response options were on a 5-point Likert-type scale from “not at all confident” to “very confident” and dichotomized to high (“quite,” “very”) versus low (“not at all,” “a little,” “somewhat”) confidence. We chose this cut-off given our interest in PCPs who reported anything less than “high” confidence, as understanding this may provide actionable targets for future interventions aimed at improving PCP confidence in delivering thyroid cancer survivorship care.

Covariates

We obtained several physician individual and practice characteristics from the survey. Individual PCP characteristics included specialty (general medicine, family medicine, other), years in practice (<10 years, 10-19 years, 20-29 years, >30 years), gender, and race (White, non-White). Respondent PCPs were also asked to report what source was the most influential in their decisions on how to treat thyroid nodule and thyroid cancer patients (training in medical school/residency, recently published clinical guidelines, practice colleagues, employer published treatment guidelines, national meetings, respected experts in my field, or journal articles) and which clinical guidelines they had read (“2015 American Thyroid Association [ATA] Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer,” National Comprehensive Cancer Network”s [NCCN] 2017 “Thyroid Carcinoma: Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology,” or none; answers were combined as reading either guideline vs none). PCP-reported practice characteristics included main practice location (large medical group/staff-model HMO or private practice/community health clinic) and number of patients typically seen in their primary practice location (≤75 patients, 76-100 patients, >100 patients).

We included two additional measures that we believe conceptually may influence PCP involvement. Based on previously developed questions (21), we assessed PCP attitudes and beliefs regarding their role in thyroid cancer survivorship care. Respondents were asked to report (on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) their level of agreement on the following statements: a) “PCPs have the skills necessary to initiate appropriate screening to detect recurrent thyroid cancer,” and b) PCPs should have responsibility for providing continuing care after treatment.” Responses were dichotomized to “strongly disagree,” “somewhat disagree,” and “neither disagree nor agree” vs “somewhat agree” and “strongly agree.”

Statistical analyses

Basic descriptive statistics were generated for all categorical variables. Using Rao-Scott chi-squared tests, we examined associations between PCP involvement in long-term surveillance and PCP individual (years in practice, most influential source in their decisions on how to treat thyroid nodule and thyroid cancer patients [limited to recently published clinical guidelines and practice colleagues due to relatively small sample sizes for all other options], clinical guidelines read) and practice (main practice location, number of patients typically seen) characteristics and attitudes and beliefs (PCPs have the skills to initiate appropriate screening to detect recurrence and PCPs should have the responsibility to provide continuing care after treatment). We then examined the same associations using multivariable logistic regression models. We report odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for regression models, with P values < 0.05 considered to be statistically significant. We then examined associations between PCP involvement in long-term surveillance and PCP confidence in handling key aspects of thyroid cancer survivorship care (role of random thyroglobulin levels in long-term surveillance, role of neck ultrasounds in long-term surveillance, when to end long-term surveillance, and when to refer back to the specialist) using Rao-Scott chi-squared tests. Multivariable logistic regression modeling was not performed due to a lack of sufficient statistical power.

All statistical analyses incorporated weights to account for our sampling strategy and reduce potential nonresponse bias. The weight includes information about the SEER site and the physician’s thyroid cancer patients treated. All analyses were performed using Stata 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas).

Results

Table 1 describes our sample individual and practice characteristics, and attitudes and beliefs. The majority of PCPs were White (67.3%), working in private practice (74.1%), and practicing for more than 20 years (63.2%). Nearly three-quarters of the respondents (72.1%) had not read either the ATA or NCCN guidelines for thyroid cancer, however 54.3% did note recently published clinical guidelines as the most influential source in their decision on how to treat thyroid nodule and cancer patients. Over half of the respondents (62%) somewhat/strongly agreed with the statement “PCPs have the skills necessary to initiate appropriate screening to detect recurrence” while 53% somewhat/strongly agreed with “PCPs should have responsibility for providing continuing care after treatment.”

Table 1.

PCP-Reported Characteristics

| Characteristics | No. (weighted %) |

|---|---|

| Individual | |

| Specialty | |

| General medicine | 72 (45.0) |

| Family medicine | 79 (50.0) |

| Other | 8 (5.1) |

| Years in practice | |

| 1–9 years | 25 (15.8) |

| 10–19 years | 34 (21.0) |

| 20–29 years | 55 (35.3) |

| 30 + years | 44 (27.9) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 74 (47.1) |

| Male | 84 (52.9) |

| Race | |

| White | 103 (67.3) |

| Non-White | 52 (32.7) |

| Clinical guidelines read | |

| ATA or NCCN or both | 44 (27.9) |

| None | 111 (72.1) |

| Most influential source in treating thyroid cancer | |

| Training in medical school/residency | 36 (22.5) |

| Clinical guidelines | 88 (54.3) |

| Colleagues in practice | 64 (39.1) |

| Employer established treatment guidelines | 7 (4.2) |

| National meetings | 28 (17.6) |

| Experts in my field | 33 (20.2) |

| Journal articles | 39 (24.4) |

| Practice | |

| Main practice location | |

| Large medical center | 37 (25.9) |

| Private | 103 (74.1) |

| Number of patients seen/typical week | |

| ≤75 | 52 (32.9) |

| 76-100 | 63 (39.6) |

| >100 | 44 (27.5) |

| Attitudes and beliefs | |

| PCP have the skills necessary to initiate appropriate screening to detect recurrent thyroid cancer | 98 (62.0) |

| PCPs should have responsibility for providing continuing care after treatment | 84 (53.0) |

*ATA = 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer

*NCCN = National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s 2017 “Thyroid Carcinoma: Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology”

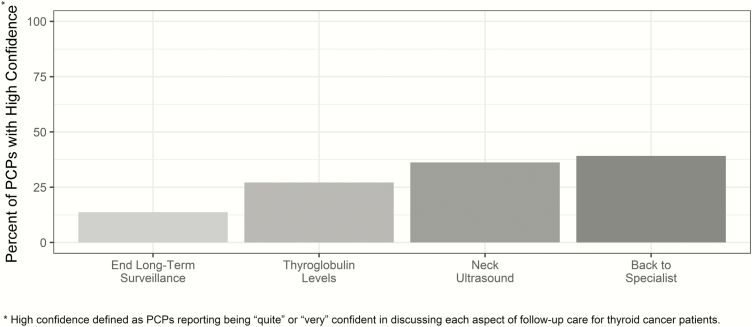

The majority of PCPs (76.0%) reported sometimes to almost always being involved in long-term surveillance. A total of 5% reported “never,” 19% “rarely, 34% “sometimes,” 24% “often,” and 18% “almost always.” Figure 1 shows the percentage of PCPs reporting having high confidence in handling several key aspects of thyroid cancer survivorship care. While this varied, it was consistently less than 50%: when to refer back to the specialist (39.1%), role of neck ultrasound in long-term surveillance (36.2%), role of random thyroglobulin levels (27.2%), and when to end long-term surveillance (13.8%).

Figure 1.

Distribution of PCP report of having high confidence in discussing key aspects of thyroid cancer survivorship care.

In bivariate analyses examining associations between PCP involvement in long-term surveillance and PCP individual and practice characteristics and attitudes and beliefs, PCPs who had read either the ATA or NCCN guidelines (compared with those who had not) were more likely to report being involved (88.4% vs 70.9%; P = 0.03). PCPs who reported recently published clinical guidelines as being the most influential in their decision on how to treat thyroid cancer patients were also more likely to report being involved (83.7% vs 66.6%; P = 0.01) (data not shown). In multivariable logistic regression models (Table 2), PCPs who reported recently published clinical guidelines as being the most influential in treating thyroid cancer patients had increased odds of reporting involvement in long-term surveillance (OR 4.29; 95% CI, 1.56-11.82). Additionally, PCPs who somewhat/strongly agreed with the belief that PCPs have the skills necessary to initiate appropriate screening to detect recurrence had increased odds of reporting involvement (OR 4.21; 95% CI, 1.58-11.21).

Table 2.

Multivariable Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals of PCP Individual and Practice Characteristics, and Attitudes and Beliefs Associated with PCP Involvement in Long-Term Surveillance of Thyroid Cancer

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Years in practice | ||

| 1-9 years | Ref | |

| 10-19 years | 0.68 | 0.13-3.48 |

| 20-29 years | 0.74 | 0.17-3.30 |

| ≥30 years | 0.88 | 0.17-4.49 |

| Number of patients seen/typical week | ||

| ≤75 patients | Ref | |

| 76-100 patients | 1.66 | 0.55-5.02 |

| >100 patients | 0.97 | 0.30-3.20 |

| Clinical guidelines read | ||

| None | Ref | |

| ATA or NCCN or both | 2.30 | 0.66-7.96 |

| Guidelines are the most influential source in treating thyroid cancer | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 4.29 | 1.56-11.82 |

| Colleagues are the most influential source in treating thyroid cancer | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.24 | 0.49-3.17 |

| Practice setting | ||

| Large medical center | Ref | |

| Private practice | 0.82 | 0.29-2.34 |

| PCP have the skills necessary to initiate appropriate screening to detect recurrent thyroid cancer | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 4.21 | 1.58-11.21 |

| PCPs should have responsibility for providing continuing care after treatment | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 0.54 | 0.18-1.58 |

*ATA = 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer

*NCCN = National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s 2017 “Thyroid Carcinoma: Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology”

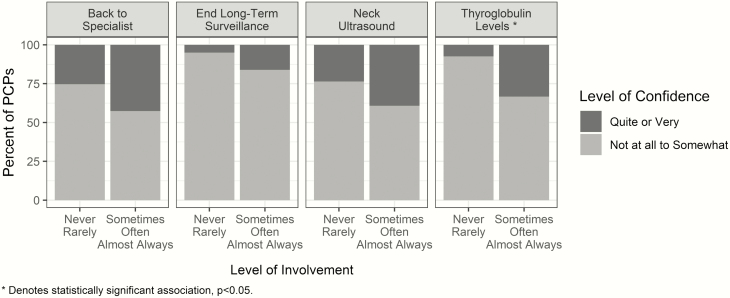

Figure 2 shows the association between PCP involvement in long-term surveillance and PCP confidence in handling key aspects of thyroid cancer survivorship care. PCPs who were involved in long-term surveillance were more likely to report having high confidence in discussing the role of random thyroglobulin levels in long-term surveillance (33.4% vs 7.4% for PCPs who were not involved; P < 0.01). We did not find statistically significant associations between PCP involvement and the other aspects of thyroid cancer survivorship care (role of neck ultrasounds in long-term surveillance, when to end long-term surveillance, and when to refer back to the specialist).

Figure 2.

Distribution of PCP confidence in discussing key aspects of thyroid cancer survivorship care by level of PCP involvement in long-term surveillance of thyroid cancer.

Discussion

In our sample of PCPs caring for a population-based cohort of thyroid cancer patients, the majority reported being involved at some level in thyroid cancer long-term surveillance. However, the proportion of PCPs reporting high confidence in discussing several key aspects of survivorship care was consistently low. While these findings are promising in showing existing PCP involvement in thyroid cancer survivorship, they also suggest tangible opportunities to better support PCPs in engaging in team-based care delivery for thyroid cancer survivors.

To our knowledge, our results are the first to characterize PCP-reported involvement in the care of thyroid cancer survivors and adds to existing literature on other cancer types. Using claims data, it was shown that indeed nearly three-quarters of breast, colon, and prostate cancer patients see their PCPs after completing their primary treatment for their cancer; however, the content of the visit—namely whether survivorship care was discussed—is unknown (22). Klabunde and colleagues examined this by surveying PCPs regarding follow-up care for breast and colon cancer survivors (23). While the majority of PCPs reported involvement, this often entailed co-management with the medical oncologist and not directly providing the care. For example, in screening for recurrent breast cancer, 18% of PCPs directly provided this care while 38% co-managed. Our results address this knowledge gap for thyroid cancer; we probed PCPs specifically regarding their involvement in monitoring for cancer progression or recurrence for thyroid cancer survivors, and show that, in fact, over two-thirds of PCPs report involvement in surveillance. This will be an important benchmark to recognize as models of team-based care are considered for thyroid cancer.

We found that PCPs who noted guidelines to be influential in directing their management of thyroid cancer patients were more likely to be involved in long-term surveillance. As learned from studies in other cancer types, encouraging primary care involvement in survivorship care has been challenging. Though survivorship care plans were created to facilitate the transition from cancer specialists to primary care, they have consistently poor uptake (24), and are both time-consuming to complete and cumbersome to follow. Additionally, there remains uncertainty to both patients and providers around who—cancer specialist or PCP—handles the various aspects of survivorship care (25, 26). In a survey of thyroid cancer survivors, the majority (90.6%) agreed they would be satisfied with specialist follow-up while only 15.0% reported they would with their PCP (27). National organizations, such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), have attempted to bring clarity to this with the release of clinical practice guidelines for survivorship care (28). For prostate cancer survivorship, for example, recommendations for care coordination include direct communication between the cancer specialist and PCP to determine their roles and responsibilities (29). Adopting a similar approach for thyroid cancer survivorship, with the development of guidelines clarifying the distinct roles and responsibilities for endocrinologists and PCPs, including which provider manages specific aspects of survivorship care (such as ordering neck ultrasounds for surveillance), may present one opportunity towards supporting PCP involvement.

While we found that the overwhelming majority of PCPs reported involvement in long-term surveillance, PCPs reporting high confidence in discussing several key aspects of thyroid cancer survivorship care was low. This is particularly interesting given that many of the respondents did agree that PCPs have the skills necessary to screen for recurrence. Similar low levels of confidence in handling survivorship care have been noted by PCPs for breast and colon cancer. Several reasons have been cited for this including the lack of training and knowledge, and poor communication from oncologists regarding what follow-up care entails (30). As such, opportunities for intervention to increase PCP involvement in thyroid cancer exist, and might include providing PCPs with training, such as CMEs, and ensuring timely transfer of follow-up care recommendations between primary care and endocrinology. This may also help bridge the potential disconnect between PCPs perceiving the ability to provide care but not feeling confident in doing so.

Strengths of our study include a diverse sample of PCPs, including nearly a third who are non-White and three-quarters who practice in the private setting, and a robust response rate for a physician survey. However, there are potential limitations to acknowledge. First, these results may not be generalizable to all PCPs, as our sampling strategy included those who were involved in the care of a thyroid cancer patient (via patient report). This sampling strategy, though, facilitated our ability to focus on physicians involved in thyroid cancer care, and ensured that the PCPs had some exposure to thyroid cancer, which is a rare disease. It is notable that even amongst this population of PCPs, a third reported not being involved and nearly half reported having low confidence in discussing thyroid cancer survivorship care. Second, we recognize that the survivorship period is dynamic. There remains significant uncertainty around which patients should be transitioned to a PCP from the cancer specialist and when, and it is plausible that involvement may change over time. However, this is the first study to our knowledge to characterize PCP involvement in thyroid cancer survivorship care and it serves as a foundation for future research in this area. Third, the cross-sectional nature of the survey limits our conclusions regarding temporality and causality. However, our data do suggest the need for further research, such as in-depth interviews with PCPs, to disentangle whether involvement leads to PCPs having confidence or whether having confidence promotes involvement.

Our findings expand on prior cancer survivorship literature by characterizing PCP involvement in caring for thyroid cancer survivors. Delivering high-quality, coordinated cancer survivorship care has been challenging. In general, there remains a lack of clarity and guidance around which provider—cancer specialist or PCP—handles cancer survivorship care. Therefore, understanding the factors that impact PCP involvement in thyroid cancer survivorship, and developing interventions that promote PCP confidence and support them to engage in high-quality care delivery will be critical.

Acknowledgments

The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries, under cooperative agreement 5NU58DP006344 and the NCI’s SEER Program under contract HHSN261201800015I awarded to the University of Southern California (USC). The collection of cancer incidence data in Georgia was supported by contract HHSN261201800003I, Task Order HHSN26100001 from the NCI and cooperative agreement 5NU58DP003875-04 from the CDC. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and endorsement by the State of California and State of Georgia Departments of Public Health, the NCI and the CDC or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred.

Financial Support: This work is supported by R01 CA201198 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to Dr. Haymart. Dr. Haymart is also supported by R01 HS024512 from AHRQ.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- OR

odds ratio

- PCP

primary care provider

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: Authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability: Restrictions apply to the availability of data generated or analyzed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality or because they were used under license. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.

References

- 1. American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Thyroid Cancer. Updated January 8, 2020. Accessed March 4, 2020 https://www.cancer.org/cancer/thyroid-cancer/about/key-statistics.html.

- 2. National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Thyroid Cancer. Accessed November 30, 2019 https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/thyro.html.

- 3. Davies L, Welch HG. Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973–2002. JAMA 2006;295(18):2164-2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Banerjee M, Muenz DG, Chang JT, Papaleontiou M, Haymart MR. Tree-based model for thyroid cancer prognostication. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014; 99(10):3737-3745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vigersky RA, Fish L, Hogan P, et al. The clinical endocrinology workforce: current status and future projections of supply and demand. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(9):3112-3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E.. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: The National Academy Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(5):631-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cowens-Alvarado R, Sharpe K, Pratt-Chapman M, et al. Advancing survivorship care through the National Cancer Survivorship Resource Center: developing American Cancer Society guidelines for primary care providers. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(3):147-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McCabe MS, Partridge AH, Grunfeld E, Hudson MM. Risk-based health care, the cancer survivor, the oncologist, and the primary care physician. Semin Oncol. 2013;40(6):804-812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gan T, Huang B, Chen Q, et al. Risk of recurrence in differentiated thyroid cancer: a population-based comparison of the 7th and 8th editions of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging systems. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(9):2703-2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cheung WY, Aziz N, Noone AM, et al. Physician preferences and attitudes regarding different models of cancer survivorship care: a comparison of primary care providers and oncologists. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):343-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dossett LA, Hudson JN, Morris AM, et al. The primary care provider (PCP)-cancer specialist relationship: a systematic review and mixed-methods meta-synthesis. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):156-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bober SL, Recklitis CJ, Campbell EG, et al. Caring for cancer survivors: a survey of primary care physicians. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4409-4418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Potosky AL, Han PK, Rowland J, et al. Differences between primary care physicians’ and oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1403-1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM.. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: the Tailored Design Method. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wallner LP, Li Y, McLeod MC, et al. Primary care provider-reported involvement in breast cancer treatment decisions. Cancer. 2019;125(11):1815-1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wallner LP, Abrahamse P, Uppal JK, et al. Involvement of primary care physicians in the decision making and care of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(33):3969-3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Papaleontiou M, Banerjee M, Yang D, Sisson JC, Koenig RJ, Haymart MR. Factors that influence radioactive iodine use for thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2013;23(2):219-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haymart MR, Banerjee M, Yang D, Stewart AK, Koenig RJ, Griggs JJ. The role of clinicians in determining radioactive iodine use for low-risk thyroid cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(2):259-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haymart MR, Banerjee M, Yang D, et al. Variation in the management of thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(5):2001-2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Cancer Institute. Survey of Physician Attitudes Regarding the Care of Cancer Survivors (SPARCCS). Updated May 16, 2019. Accessed March 1, 2020 https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/sparccs/.

- 22. Pollack LA, Adamache W, Ryerson AB, Eheman CR, Richardson LC. Care of long-term cancer survivors: physicians seen by Medicare enrollees surviving longer than 5 years. Cancer. 2009;115(22):5284-5295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klabunde CN, Han PK, Earle CC, et al. Physician roles in the cancer-related follow-up care of cancer survivors. Fam Med. 2013;45(7):463-474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jacobsen PB, DeRosa AP, Henderson TO, et al. Systematic review of the impact of cancer survivorship care plans on health outcomes and health care delivery. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(20):2088-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wallner LP, Li Y, Furgal AKC, et al. Patient preferences for primary care provider roles in breast cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(25):2942-2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Radhakrishnan A, Chandler McLeod M, Hamilton AS, et al. Preferences for physician roles in follow-up care during survivorship: do patients, primary care providers, and oncologists agree? J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(2):184-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bender JL, Wiljer D, Sawka AM, Tsang R, Alkazaz N, Brierley JD. Thyroid cancer survivors’ perceptions of survivorship care follow-up options: a cross-sectional, mixed-methods survey. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(5):2007-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology breast cancer survivorship care guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):611-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Resnick MJ, Lacchetti C, Penson DF; American Society of Clinical Oncology Prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines: American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline endorsement. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(3):e445-e449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lawrence RA, McLoone JK, Wakefield CE, Cohn RJ. Primary care physicians’ perspectives of their role in cancer care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(10):1222-1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]