Abstract

Objective

The aim of the present study was to determine the prevalence of overactive bladder (OAB) in individuals aged ≥40 years in China, Taiwan, and South Korea.

Methods

The present cross‐sectional population‐representative Internet‐based study investigated OAB symptoms in men and women aged ≥40 years using the overactive bladder symptom score. Additional instruments included the International Index of Erectile Function (men only) and the Sexual Quality of Life – Female (women only) questionnaires, as well as Patient Perception of Bladder Condition (PPBC).

Results

In all, 8284 individuals participated in the study. The prevalence of OAB was 20.8% overall (women 22.1%, men 19.5%) and increased significantly with age, from 10.8% in those aged 40–44 years to 27.9% in those aged >60 years (P = .001). The presence of comorbid conditions (e.g. neurological disease, diabetes) was associated with a significantly increased prevalence of OAB. Increasing symptom severity was associated with significantly worsening patient perception of bladder condition responses. Just under half (48%) of those with no OAB had no lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), whereas 88% of those with severe symptoms had all 3 LUTS (International Continence Society definition) symptom categories (voiding, post‐micturition, and storage symptoms). Of those without OAB, 10% reported visiting healthcare professionals for urinary symptoms, compared with 64% of those with severe OAB symptoms (P = .001). Increased symptom severity was significantly associated with lower sexual quality of life in both men and women.

Conclusions

OAB symptoms were found to affect 1 in 5 individuals aged ≥40 years in China, Taiwan, and South Korea, becoming more common with increasing age. The results suggest that many more individuals with OAB could benefit by consulting healthcare professionals.

Keywords: China, overactive bladder, prevalence, Republic of Korea, Taiwan

1. INTRODUCTION

Overactive bladder (OAB) is typically characterized by urinary urgency, frequency, and nocturia.1 Some patients also experience urgency urinary incontinence. OAB symptoms can be idiopathic (non‐neurological; i.e. due to bladder outlet obstruction or no obvious cause) or caused by neurological conditions (e.g. diabetic neuropathy, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury).2 Various treatments are available for patients with OAB, with anticholinergic or β3‐adrenoceptor agonist medications used in many cases.

Several large epidemiological studies of urinary tract symptoms have been performed in Europe and North America. In the Epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study, conducted in the US, UK, and Sweden, the prevalence of OAB in adults aged ≥40 years was variable, depending on sex and the definition of OAB used.3, 4 When OAB was defined as the presence of urinary urgency (at least “sometimes”) or the presence of urinary urgency incontinence, the reported prevalence rates in Sweden, the UK, and US were 22%, 24%, and 27%, respectively, in men and 41%, 42%, and 43%, respectively, in women.4 An overall OAB prevalence of 11.8% was reported in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study of adults aged ≥18 years in Canada, Germany, Italy, Sweden, and the UK.5 Previous studies reported an OAB prevalence of 16.5% in a US population aged ≥18 years6 and 16.6% in European individuals aged ≥40 years.7 Few international population‐based data are available regarding the prevalence of OAB in Asia, and there is considerable variation between published estimates.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Consequently, our understanding of the true burden of OAB in Asia is limited.

The aim of the present study was to determine the prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in the population aged ≥40 years in China, Taiwan, and South Korea, using symptom definitions approved by the International Continence Society (ICS) in 2002.18 LUTS prevalence has been reported previously.19 Herein we report on OAB prevalence results from that study.

2. METHODS

A cross‐sectional population‐representative Internet‐based study was conducted in China, Taiwan, and South Korea. Full details of the study methodology have been published elsewhere.19 Individuals aged ≥40 years with Internet access and the ability to read the local language were eligible to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were pregnancy and urinary tract infection within the preceding month. All participants provided informed consent.

Participants were from consumer survey panels with random sampling, and were representative of the target population. Cohort management accounted for sex, age, income, age group, and geography (restricted to urban areas). For each participant, general demographic data were collected. The instruments used in the study included the overactive bladder symptom score20 (OABSS), the International Index of Erectile Function21 (IIEF; completed by men only), Sexual Quality of Life – Female questionnaire22 (SQOL‐F; completed by women only), and the Patient Perception of Bladder Condition23 (PPBC). All instruments were validated in the local language. Diagnostic criteria for OAB were a total OABSS ≥3 with an urgency score ≥2. Participants were asked whether they followed treatment, with the following as options: prescribed medication, surgery, physical therapy, self‐treatment, limiting fluid intake, limiting caffeine intake, limit alcohol intake, stopping drinking during the night, and wearing pads.20

It was calculated that a minimum sample size of 384 panel respondents per group (1920 per country; 5760 in total) was required. Based on the assumption that approximately 28% of data would be non‐evaluable, planned enrolment was 8000 respondents (China: 4000; Taiwan: 2000; South Korea: 2000). The initial data analyses were based on descriptive statistics. Post‐stratification weighting was performed to match the age and sex distributions of populations in the different countries. All significance testing was undertaken post hoc. Five different age groups were analyzed for each country (40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, and ≥60 years). Post hoc statistical comparisons were based on the Chi‐squared test. Correlations were characterized by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient, with the exception of the relationship between OAB and PPBC, which was investigated using the Spearman method.

It was not considered necessary to submit this study for approval by an international review board because it was based on a survey. However, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed and the study was performed in compliance with market research (ESOMAR) guidelines24 and Good Clinical Practice.

3. RESULTS

The survey sample and response rate has been reported previously.19 Briefly, 495 578 email invitations were sent out and 34 802 (7.0%) responses were received. Informed consent was provided by 26 613 (76.5%) respondents. Among the 8284 individuals who completed the survey (1.7% of invitees), 4136 were from China, 2068 were from Taiwan, and 2080 were from South Korea. Demographic characteristics are given in Table 1: 50.8% of the participants were women and 34.4% were at least 60 years of age.

Table 1.

Demographic data of study participants19

| China (n = 4136) | Taiwan (n = 2068) | South Korea (n = 2080) | Overall (n = 8284) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Men | 50.3 | 48.6 | 47.6 | 49.2 |

| Women | 49.7 | 51.4 | 52.4 | 50.8 |

| Age (y) | ||||

| 40–44 | 19.9 | 15.6 | 16.9 | 18.1 |

| 45–49 | 19.6 | 16.1 | 16.8 | 18.0 |

| 50–54 | 15.3 | 16.3 | 16.3 | 15.8 |

| 55–59 | 12.7 | 14.9 | 14.4 | 13.7 |

| ≥60 | 32.6 | 37.1 | 35.6 | 34.4 |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 28.0 | 39.3 | 30.3 | 31.4 |

| Some college | 28.4 | 23.7 | 3.4 | 20.9 |

| College degree/college graduate | 40.2 | 28.2 | 57.0 | 41.4 |

| Postgraduate | 3.5 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 6.3 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 2.9 | 14.9 | 9.2 | 7.5 |

| Divorced | 1.5 | 5.2 | 4.0 | 3.0 |

| Married/living with partner | 91.7 | 72.8 | 81.6 | 84.5 |

| Widow/widower | 3.2 | 6.3 | 4.5 | 4.3 |

| Prefer not to answer | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Work status | ||||

| Homemaker | 2.6 | 12.0 | 22.4 | 9.9 |

| Retired | 28.7 | 16.9 | 6.0 | 20.1 |

| Student | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Working full‐time | 62.6 | 60.0 | 53.9 | 59.8 |

| Working part‐time | 3.7 | 6.2 | 8.0 | 5.4 |

| Other work for pay | 0.4 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 1.2 |

| Other | 1.1 | 1.9 | 3.7 | 2.0 |

| Unemployed | 0.6 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 1.2 |

| Permanently disabled/cannot work due to ill health | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

Data show the percentage of individuals in each group.

The overall prevalence of OAB was 20.8% (Table 2). The prevalence of OAB was significantly higher in China than in South Korea or Taiwan (23.9% vs. 19.7% and 15.8%, respectively; P = .001). In addition, OAB was significantly more prevalent among women than men (22.1% vs. 19.5%, respectively; P = .004). OAB prevalence increased significantly with age, from 10.8% among those aged 40–44 years to 27.9% in those aged >60 years (P = .001; Table 3); this trend was evident for both men and women. OAB prevalence varied by marital status (P = .001), with the lowest rates in those preferring not to disclose their marital status (11.5%) or who were single (12.7%) and the highest rate in widows or widowers (24.2%). Educational level was also associated with differences in OAB prevalence (P = .002), with the lowest rate reported among individuals with postgraduate education (17.9%) and the highest rate among those who had received some college education (23.3%). There were no significant differences in OAB prevalence according to work status. Considering the overall population, there was no relationship between OAB presence or severity and body mass index (BMI; data not shown; mean [± s.d.] BMI for the overall population 23.4 ± 3.6 kg/m2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of overactive bladder by severity, sex and country

| China (n = 4136) | Taiwan (n = 2068) | South Korea (n = 2080) | Overall (n = 8284) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | ||||

| No symptoms | 1634 (78.6) | 797 (80.5) | 849 (84.4) | 3279 (80.5) |

| Mild symptoms | 116 (5.6) | 105 (10.6) | 63 (6.2) | 283 (6.9) |

| Moderate symptoms | 311 (15.0) | 86 (8.7) | 89 (8.8) | 486 (11.9) |

| Severe symptoms | 19 (0.9) | 2 (0.2) | 5 (0.5) | 27 (0.7) |

| Total prevalence | 446 (21.4) | 157 (15.6) | 194 (19.5) | 796 (19.5) |

| Women | ||||

| No symptoms | 1513 (73.6) | 873 (80.1) | 893 (84.1) | 3279 (77.9) |

| Mild symptoms | 125 (6.1) | 105 (9.6) | 62 (5.8) | 292 (6.9) |

| Moderate symptoms | 390 (19.0) | 107 (9.8) | 102 (9.6) | 599 (14.2) |

| Severe symptoms | 28 (1.4) | 5 (0.5) | 5 (0.5) | 38 (0.9) |

| Total prevalence | 543 (26.4) | 169 (15.9) | 217 (19.9) | 930 (22.1) |

| Men and women combined | ||||

| No symptoms | 3147 (76.1) | 1742 (84.2) | 1669 (80.3) | 6558 (79.2) |

| Mild symptoms | 241 (5.8) | 125 (6.0) | 210 (10.1) | 575 (6.9) |

| Moderate symptoms | 701 (16.9) | 191 (9.2) | 193 (9.3) | 1085 (13.1) |

| Severe symptoms | 47 (1.1) | 11 (0.5) | 8 (0.4) | 65 (0.8) |

| Total prevalence | 989 (23.9) | 326 (15.8) | 411 (19.8) | 1726 (20.8) |

Data show the number of individuals in each group, with percentages in parentheses. Numbers of individuals are weighted and rounded, therefore category totals may not equal population totals shown in column headings. Percentages are based on the weighted n values.

Table 3.

Prevalence of overactive bladder (OAB) by demographic characteristics

| Men (n = 4076) | Women (n = 4208) | Men and women (n = 8284) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | |||

| 40–44 | 82 (10.8) | 81 (10.9) | 162 (10.8) |

| 45–49 | 114 (15.2) | 114 (15.4) | 228 (15.3) |

| 50–54 | 122 (18.4) | 140 (21.5) | 261 (20.0) |

| 55–59 | 116 (20.5) | 161 (28.4) | 277 (24.5) |

| ≥60 | 363 (27.0) | 434 (28.7) | 797 (27.9) |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 200 (19.3) | 296 (19.0) | 496 (19.1) |

| Some college | 163 (19.5) | 242 (27.0) | 405 (23.3) |

| College degree/college graduate | 388 (21.0) | 343 (21.7) | 731 (21.3) |

| Postgraduate | 45 (12.8) | 48 (28.7) | 93 (17.9) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/living with partner | 714 (20.2) | 791 (22.9) | 1505 (21.5) |

| Single | 40 (13.2) | 38 (12.2) | 79 (12.7) |

| Widow/widower | 19 (22.2) | 67 (24.9) | 86 (24.2) |

| Divorced | 21 (18.0) | 28 (21.0) | 49 (19.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (6.6) | 5 (15.8) | 7 (11.5) |

| Work status | |||

| Working full‐time | 479 (17.1) | 436 (20.1) | 928 (18.7) |

| Working part‐time | 53 (26.3) | 48 (19.6) | 104 (23.3) |

| Unemployed | 8 (15.0) | 10 (20.8) | 19 (19.1) |

| Retired | 228 (27.3) | 230 (31.0) | 477 (28.7) |

| Homemaker | 3 (11.0) | 122 (16.4) | 141 (17.2) |

| Other work for pay | 10 (15.7) | 6 (18.2) | 16 (16.0) |

| Permanently disabled/cannot work due to ill health | 5 (36.8) | 6 (46.2) | 13 (42.5) |

| Student | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (10.8) |

| Other | 10 (12.2) | 16 (20.5) | 26 (16.2) |

Data show the number of individuals in each group, with percentages in parentheses. Numbers of individuals are weighted and rounded, therefore category totals may not equal population totals shown in column headings. Percentages are based on the weighted n values.

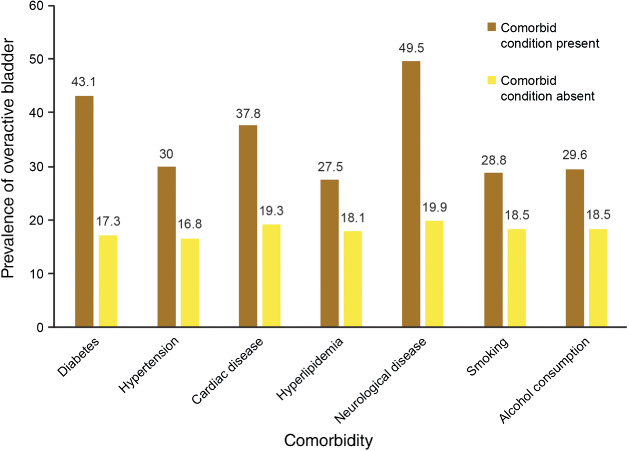

The presence of comorbid conditions was associated with statistically significant increases in OAB prevalence (Figure 1; P = .001 for all comorbidities). This was true for all comorbid conditions that were analyzed, with neurological disease and diabetes being associated with the greatest increases in OAB prevalence.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of overactive bladder (OAB) in individuals with and without comorbid conditions.

Almost half of the individuals with no OAB (48%) had no LUTS according to ICS criteria (Table 4). Conversely, 88% of individuals with severe OAB were positive for all 3 ICS symptom groups (voiding, storage, and post‐micturition). Individuals without OAB were most likely to report that their bladder condition does not cause them any problems (60%; vs. 0% of individuals with severe OAB), whereas those with severe OAB were most likely to be experiencing many severe bladder‐related problems (25%; vs. 0% of individuals with no OAB). These data represent a statistically significant correlation between OAB and PPBC (r = 0.753, P = .001).

Table 4.

Lower urinary tract symptoms (International Continence Society [ICS] definitions) and Patient Perception of Bladder Condition (PPBC) measure according to severity of overactive bladder (OAB)

| No OAB (n = 6558) | Mild OAB (n = 575) | Moderate OAB (n = 1085) | Severe OAB (n = 65) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICS | ||||

| No LUTS | 3160 (48.2) | 43 (7.4) | 10 (1.0) | 1 (1.5) |

| Voiding only | 356 (5.4) | 13 (2.2) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Storage only | 1313 (20.0) | 109 (18.9) | 94 (8.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| PM only | 141 (2.2) | 8 (1.4) | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Voiding + storage | 535 (8.2) | 125 (21.7) | 165 (15.2) | 7 (10.0) |

| Voiding + PM | 181 (2.8) | 9 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Storage + PM | 172 (2.6) | 32 (5.6) | 30 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Voiding + storage + PM | 702 (10.7) | 237 (41.3) | 779 (71.8) | 58 (88.4) |

| PPBC | ||||

| Does not cause me any problems at all | 3905 (59.6) | 62 (10.7) | 30 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Causes me some very minor problems | 1895 (28.9) | 257 (44.6) | 189 (17.4) | 6 (8.7) |

| Causes me some minor problems | 584 (8.9) | 190 (33.1) | 365 (33.6) | 6 (9.8) |

| Causes me (some) moderate problems | 140 (2.1) | 55 (9.6) | 307 (28.3) | 14 (21.5) |

| Causes me severe problems | 25 (0.4) | 10 (1.8) | 142 (13.1) | 23 (35.1) |

| Causes me many severe problems | 10 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 52 (4.8) | 16 (25.0) |

Abbreviation: PM, post‐micturition.

Data show the number of individuals in each group, with percentages in parentheses. Numbers of individuals are weighted and rounded, therefore category totals may not equal population totals shown in column headings. Percentages are based on the weighted n values.

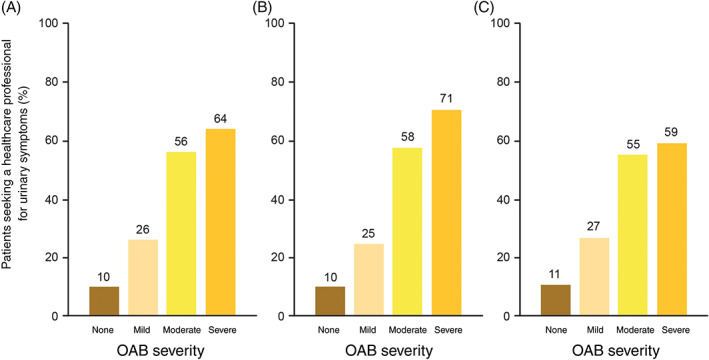

Of individuals with OAB, 46% reported visiting healthcare professionals for urinary symptoms (men 47%, women 46%). This percentage increased with increasing OAB severity (P = .001) from 10% for no OAB to 64% for severe OAB, a trend that was apparent in both men and women (Figure 2). The percentage of men with severe OAB visiting a healthcare professional for urinary symptoms was higher than that of women (71% vs. 59%, respectively), but this difference was not statistically significant (P > .05). The percentage of individuals following treatment increased significantly with OAB severity (P = .001) from 38% among those with no OAB, to 67% among those with mild OAB, to 86% among those with moderate OAB, and to 94% among those with severe OAB. The most commonly followed treatments by individuals with no OAB compared with those with severe OAB were prescribed medication (19% vs. 63%, respectively; P = .001), limiting fluid intake (10% vs. 46%, respectively; P = .001), self‐treatment (10% vs. 31%, respectively; P = .001), and physical therapy (7% vs. 37%, respectively; P = .001).

Figure 2.

Likelihood of seeking healthcare for urinary symptoms according to overactive bladder (OAB) status and severity (all countries combined) for A, the entire study population (n = 7456) and B, men (n = 3688) and C, women (n = 3768) separately

Increased severity of OAB was associated with reduced sexual quality of life (Table 5; for total score, r = –0.285, P < .0001). Among women, the mean SQOL‐F total score ranged between 76.9 for those with no OAB and 61.6 for those with severe OAB. For all 5 domains of the IIEF, including sexual desire and intercourse satisfaction, men with no OAB had the highest mean score and those with severe OAB had the lowest mean score. OABSS correlation coefficients for the 5 IIEF domain scores ranged between –0.368 (overall satisfaction) and –0.472 (orgasmic function; P < .00001 in all 5 domains).

Table 5.

Sexual function according to severity of overactive bladder (OAB)

| No OAB (n = 6558) | Mild OAB (n = 575) | Moderate OAB (n = 1085) | Severe OAB (n = 65) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SQOL‐F (women only) | ||||

| Psychosexual feelings | 25.3 ± 16.6 | 26.8 ± 14.0 | 23.8 ± 13.2 | 20.9 ± 10.5 |

| Sexual and relationship satisfaction | 15.9 ± 10.6 | 19.0 ± 9.0 | 19.4 ± 8.5 | 18.8 ± 8.8 |

| Self‐worthlessness | 11.0 ± 7.2 | 11.8 ± 5.9 | 10.5 ± 5.8 | 9.2 ± 4.7 |

| Sexual repression | 10.3 ± 7.1 | 11.1 ± 6.1 | 10.0 ± 5.7 | 9.4 ± 5.0 |

| Total score | 76.9 ± 28.9 | 72.3 ± 29.1 | 67.4 ± 25.6 | 61.6 ± 21.4 |

| IIEF (men only) | ||||

| Erectile function | 23.1 ± 6.8 | 21.3 ± 7.6 | 16.9 ± 6.5 | 16.0 ± 6.8 |

| Orgasmic function | 7.9 ± 2.5 | 7.3 ± 2.7 | 5.7 ± 2.3 | 5.2 ± 2.2 |

| Sexual desire | 7.0 ± 2.1 | 6.6 ± 2.3 | 5.7 ± 1.9 | 5.3 ± 2.0 |

| Intercourse satisfaction | 9.3 ± 3.2 | 8.5 ± 3.1 | 7 ± 3 | 6.7 ± 3.0 |

| Overall satisfaction | 6.8 ± 2.1 | 6.5 ± 2.4 | 5.4 ± 1.9 | 4.9 ± 1.9 |

Data are the mean ± SD scores on the Sexual Quality of Life – Female (SQOL‐F) and International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) questionnaires. A higher score reflects a better quality of life on both measures.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study shows that 20.8% of the population aged ≥40 years in China, Taiwan, and South Korea fulfilled the OABSS criteria for OAB. The prevalence of OAB increased with age and was higher in women than men. The risk of OAB was higher among individuals with a range of comorbidities, particularly neurological disease and diabetes. Increased severity of OAB was associated with decreased sexual quality of life, among both men and women. Demographic data show that individuals aged ≥40 years comprise 43%, 49%, and 48% of the overall population in China, Taiwan, and South Korea, respectively. Due to low OAB prevalence rates among individuals aged <40 years, overall population prevalence rates of OAB are expected to be lower than the rates reported in the study population. However, due to the similarity of the population age distributions, the variations between countries in overall population prevalence rates are expected to be similar to those reported here.

Herein we report that national OAB prevalence rates range between 23.9% (China) and 15.8% (Taiwan). The differences between countries could be related to a variety of different factors, including demographic variations in the study populations of the 3 countries, cultural differences (questions may not be interpreted consistently), lifestyle differences (factors such as obesity and caffeine consumption, which affect the risk of OAB, may not be consistent across countries), and ethnicity (some nationalities may be genetically more susceptible to OAB than others).

The association between OAB prevalence and age is not surprising because numerous previous studies of OAB in Europe and North America,6, 7 as well as Asia,8, 9, 10, 13, 14, 17 have reported that the prevalence of OAB generally increases with age. Similarly, the finding that individuals with neurological conditions have a much higher likelihood of OAB is expected because these individuals would be more likely to have detrusor overactivity. In the present study, marital status and educational level were found to also be associated with differences in OAB prevalence. The first of these associations may, potentially, be attributable to age. Single individuals (low OAB prevalence; mean age 44 years) were younger than the overall study population (mean age 54 years), and widows or widowers (high OAB prevalence; mean age 80 years) were older. The reasons for the variation according to educational level are not clear.

The present data indicate that severe OAB is highly likely to present with other LUTS. Most individuals with severe OAB (88%) were positive for all 3 ICS symptom groups. Therefore, in a patient presenting with OAB, it may be valuable to assess whether other symptoms are present to ensure appropriate treatment of all the patient's LUTS.

The OAB prevalence data in the present study appear broadly comparable with previous studies performed in Europe and North America. The overall prevalence in the present study (20.8%) was higher than that observed in the EPIC study (11.8%)5 and the National Overactive Bladder Evaluation (NOBLE) program (16.5%).6 In the present study, the population was aged ≥40 years, compared with ≥18 years in these previous 2 studies; this could have contributed to the observed differences among studies. There was no such age difference between the present study and a European telephone‐based study reporting an OAB prevalence of 16.6%,7 but this could be attributable to different methodologies (e.g. individuals may answer questions differently on the telephone compared with online).

Previous OAB prevalence studies conducted in Asia have reported variable results. Two previous studies in China have reported considerably lower OAB prevalence than the rate of 23.9% reported herein. Specifically, Wen et al.15 reported an OAB prevalence of 2.1%; as in the present study, OAB presence in that study was determined according to the OABSS and the population was aged ≥40 years. In another Chinese study, performed using ICS definitions in a population aged ≥18 years, OAB prevalence was 6.0%.14 However, an OAB prevalence of 26.3% based on IPSS was reported in a Chinese study of men aged >50 years,17 which is comparable with the prevalence of 21.4% among Chinese men aged ≥40 years in the present study.

A previous Korean study reported OAB prevalence to be 12.2%,11 below the rate of 19.7% reported herein, but this difference could be attributable to the population in the other study being aged ≥18 years. One Taiwanese study reported adult OAB prevalence to be 16.9%,16 similar to the rate of 15.8% in Taiwanese men and women in the present study. However, another study conducted in Taiwan (in women only) reported higher OAB prevalence, ranging between 21.0% and 34.8% depending on the OAB definition used.8 OAB prevalence rates above the levels reported herein have also been observed in 2 international Asian studies. Moorthy et al.13 reported an OAB prevalence of 29.9% in Asian men, and Lapitan and Chye10 estimated the prevalence among women to be 53.1%. Overall, differences between studies in OAB prevalence could be attributable to different criteria used to define OAB, and variations in age, culture, and ethnicity.

In the present study, OAB prevalence was higher in women than men, similar to findings from the EPIC study,5 the NOBLE program,6 and the European telephone‐based study.7 In the EpiLUTS study, participants were aged ≥40 years and OAB prevalence was higher in women, but the difference between the sexes was larger (31%–43% in women vs. 13%–27% in men).4 Higher OAB prevalence among women than men has been reported in Korea.11 In contrast, other Asian studies suggest a higher prevalence of OAB in men.9, 12, 15 Differences between study populations with regard to age may have contributed to these findings. Matsumoto et al.12 reported that the prevalence of OAB increased with age in men; although the same was observed in women, the magnitude of the trend was reduced. Accordingly, in a Taiwanese study, increased age was an independent risk factor for OAB in men but not in women.16 The data from the study of Matsumoto et al.12 suggest that OAB affects a higher proportion of women than men below the age of 50 years, but a higher proportion of men than women above the age of 50 years. In the present study, the relationship between age and OAB prevalence did not clearly differ between men and women, although, unlike men, women in the 2 oldest age groups (55–60 and >60 years) showed very similar rates of OAB.

The present study found that 46% of individuals with OAB were consulting a healthcare professional and that 67%–93% were receiving treatment for their condition. The most common forms of treatment were prescribed medication, limiting fluid intake, self‐treatment, and physical therapy. The lack of healthcare professional consultation by 54% of individuals with OAB means that this population is unlikely to be receiving the most effective available treatment for their condition and may be experiencing a greater impairment of their quality of life than necessary. Education of the general population regarding OAB treatment could potentially reduce the real‐life effects of OAB.

The observed associations between increasing OAB severity and decreasing sexual quality of life, among both men and women, are consistent with results of previous studies.25, 26 This effect of OAB, although not surprising, can be an important reason for individuals to seek effective treatment. However, it should be borne in mind that sexual quality of life is influenced by a wide variety of factors in addition to OAB (e.g. marital status, education, socioeconomic status, mental health, and all types of LUTS).

The large number of participants is an important strength of the present study, as is the use of a well‐established, internationally validated20, 27, 28 instrument to determine the prevalence of OAB. We selected countries with the highest Internet penetration rates in Asia (South Korea, [92%], Taiwan [84%] and China [50%]) at the time of the study (http://www.internetworldstats.com/; accessed 18 August 2017). In addition, we considered the online survey approach to be more appropriate than a face‐to‐face survey to assess sensitive questions such as those relating to sexual health function (data will be reported elsewhere). However, OAB prevalence may be different in individuals without Internet access, or individuals completing the questionnaires may not interpret all the questions in the intended manner. Studies using a healthcare professional as an interviewer can reduce this risk through explanations of questions should the interviewee have any uncertainties. Other limitations of the present study include the use of a volunteer consumer panel and potential bias towards individuals of higher socioeconomic class or educational level that may have been compounded by restriction to urban areas. In addition, we did not include pharmacoeconomic analyses of OAB.

In conclusion, OAB symptoms affect 1 in 5 men and women aged ≥40 years in China, Taiwan, and South Korea, and these symptoms become more common with increasing age. Although a significant proportion of individuals with OAB are being treated, the results suggest that many more individuals with OAB could benefit by consulting healthcare professionals to ensure that they receive the most effective available treatment. The findings reported herein have set the scene for further epidemiological studies across Asia to analyze the prevalence of OAB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the study participants for their time, Nanjangud Shankar Narasimha Murthy, Dept. of Community Medicine – SIMSRC, Bangalore, India and Raviprakash Koni, Stratycon Business Solutions Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore, India for statistical analyses, and Ming Liu Department of Urology, Beijing Hospital, Beijing, China for intellectual input into the manuscript. This study was funded by Astellas Pharma Singapore Pte. Ltd. Medical writing support was provided by Ken Sutor and Jackie van Bueren of Envision Scientific Solutions and funded by Astellas Pharma Global Development.

DISCLOSURE

All authors have acted as consultants for Astellas during a meeting to discuss the publications from the study. Tag Keun Yoo has received grants and personal fees from Astellas to act as a consultant to Astellas. Romeo Chu is a former employee of Astellas. Budiwan Sumarsono is an employee of Astellas.

ORCID

Kyu‐Sung Lee http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0891-2488

Chuang Y‐C, Liu S‐P, Lee K‐S, et al. Prevalence of overactive bladder in China, Taiwan and South Korea: Results from a cross‐sectional, population‐based study. Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. 2019;11:48–55. 10.1111/luts.12193

This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT02618421).

Funding information Astellas Pharma Singapore Pte Ltd, Grant/Award number: n/a

REFERENCES

- 1. Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Faraday M, Vasavada SP, American Urological Association, Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine . Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non‐neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline amendment. J Urol. 2015;193:1572–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jayarajan J, Radomski SB. Pharmacotherapy of overactive bladder in adults: a review of efficacy, tolerability, and quality of life. Res Rep Urol. 2013;6:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Thompson CL, et al. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in the USA, the UK and Sweden: results from the Epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study. BJU Int. 2009;104:352–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Weinstein D, et al. The prevalence of OAB in the US, UK and Sweden: results from EpiLUTS. J Urol. 2009;181 (Suppl):160. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, et al. Population‐based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol. 2006;50:1306–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stewart WF, Van Rooyen JB, Cundiff GW, et al. Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States. World J Urol. 2003;20:327–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Milsom I, Abrams P, Cardozo L, Roberts RG, Thuroff J, Wein AJ. How widespread are the symptoms of an overactive bladder and how are they managed? A population‐based prevalence study. BJU Int. 2001;87:760–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen YC, Ng SC, Chen SL, Huang YH, Hu SW, Chen GD. Overactive bladder in Taiwanese women: re‐analysis of epidemiological database of community from 1999 to 2001. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:56–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Homma Y, Yamaguchi O, Hayashi K, Neurogenic Bladder Society Committee . An epidemiological survey of overactive bladder symptoms in Japan. BJU Int. 2005;96:1314–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lapitan MC, Chye PL, Asia‐Pacific Continence Advisory Board . The epidemiology of overactive bladder among females in Asia: a questionnaire survey. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12:226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee YS, Lee KS, Jung JH, et al. Prevalence of overactive bladder, urinary incontinence, and lower urinary tract symptoms: results of Korean EPIC study. World J Urol. 2011;29:185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matsumoto S, Hashizume K, Wada N, et al. Relationship between overactive bladder and irritable bowel syndrome: a large‐scale Internet survey in Japan using the Overactive Bladder Symptom Score and Rome III criteria. BJU Int. 2013;111:647–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moorthy P, Lapitan MC, Quek PL, Lim PH. Prevalence of overactive bladder in Asian men: an epidemiological survey. BJU Int. 2004;93:528–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang Y, Xu K, Hu H, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and impact on health related quality of life of overactive bladder in China. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:1448–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wen JG, Li JS, Wang ZM, et al. The prevalence and risk factors of OAB in middle‐aged and old people in China. Neurourol Urodyn. 2014;33:387–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yu HJ, Liu CY, Lee KL, Lee WC, Chen TH. Overactive bladder syndrome among community‐dwelling adults in Taiwan: prevalence, correlates, perception, and treatment seeking. Urol Int. 2006;77:327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang XH, Li X, Zhang Z, et al. Prevalence of overactive bladder in a community‐based male aging population. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2010;48:1763–1766. (Chinese with English abstract). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub‐committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chapple C, Castro‐Diaz D, Chuang YC, et al. Prevalence of LUTS in China, Taiwan and South Korea: results from a cross‐sectional, population‐based study. Adv Ther. 2017. doi 10.1007/s12325‐017‐0577‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Homma Y, Yoshida M, Seki N, et al. Symptom assessment tool for overactive bladder syndrome – overactive bladder symptom score. Urology. 2006;68:318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Symonds T, Boolell M, Quirk F. Development of a questionnaire on sexual quality of life in women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31:385–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Coyne KS, Matza LS, Kopp Z, Abrams P. The validation of the patient perception of bladder condition (PPBC): a single‐item global measure for patients with overactive bladder. Eur Urol. 2006;49:1079–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. ESOMAR . ESOMAR guideline for online research. https://www.esomar.org/uploads/public/knowledge-and-standards/codes-and-guidelines/ESOMAR_Guideline-for-online-research.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2016.

- 25. Coyne KS, Margolis MK, Jumadilova Z, Bavendam T, Mueller E, Rogers R. Overactive bladder and women's sexual health: what is the impact? J Sex Med. 2007;4:656–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Irwin DE, Milsom I, Reilly K, et al. Overactive bladder is associated with erectile dysfunction and reduced sexual quality of life in men. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2904–2910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hung MJ, Chou CL, Yen TW, et al. Development and validation of the Chinese Overactive Bladder Symptom Score for assessing overactive bladder syndrome in a RESORT study. J Formos Med Assoc. 2013;112:276–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jeong SJ, Homma Y, Oh SJ. Korean version of the Overactive Bladder Symptom Score questionnaire: translation and linguistic validation. Int Neurourol J. 2011;15:135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]