Abstract

The purpose of this systematic review was to locate and synthesise existing peer‐reviewed quantitative and qualitative evidence regarding enablers of psychological well‐being among refugees and asylum seekers living in transitional countries and for whom migration status is not final. Systematic searches were conducted in nine databases: Academic Search Premier, CINAHL, Embase, Emcare, Medline, Psychology and Behavioral Science, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science. Search terms were related to refugees and asylum seekers, enablers, and psychological well‐being. Studies were limited to those conducted in the last 20 years, with participants who were refugees and asylum seekers with no legal residency status, aged 16 years and above, and living in transit host countries without UNHCR resettlement programmes. This systematic review was conducted between March and June 2018 and followed the PRISMA guidelines. Results were screened by two reviewers at two stages: title and abstracts, and full‐text. Critical appraisal and data extraction were also completed by two reviewers. Initial database searching yielded 3,133 results. Following the addition of two records from relevant reference lists and the removal of duplicates, a total of 1,624 results were included for screening. A total of 16 articles were deemed eligible for inclusion in this review, reporting on a collective sample of 1,352 participants. Twelve qualitative and four quantitative studies identified eight enablers of psychological well‐being: social support; faith, religion and spirituality; cognitive strategies; education and training opportunities; employment and economic activities; behavioural strategies; political advocacy; and environmental conditions. Despite many challenges associated with forced displacement and the transit period, this review highlights multiple factors that promote well‐being and suggest areas for intervention development and resource allocation.

Keywords: asylum seekers, coping, enablers, psychological well‐being, refugees, transit

What is known about this topic

Many studies consider enablers of refugee and asylum seeker psychological well‐being in the resettlement context.

The transit period of forced displacement is associated with difficult living conditions, fear and uncertainty regarding the future, and mental health problems.

Currently, we are witnessing the largest numbers of displaced people on record, with a large proportion residing in transitional host countries awaiting durable solutions.

What this paper adds

A synthesis of available literature concerning enablers of psychological well‐being for refugees and asylum seekers living in transitional host countries is presented.

Social, religious and cultural strengths and resources; future‐orientated mindset; and finding meaning and purpose in life, despite displacement appears integral for psychological well‐being in this context.

1. INTRODUCTION

At the end of 2017, approximately 68.5 million people were displaced globally due to conflict, violence, persecution, and human rights abuses (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR], 2018). Of these, approximately 28.5 million were refugees and asylum seekers who had fled from their country of origin and were residing in transition countries—in host communities, camps, and detention facilities (UNHCR, 2018). These figures are the highest on record and highlight that vast and growing numbers of displaced people are living in a transitional state and with unresolved migration status. Millions of refugees and asylum seekers are unable to return home after becoming displaced and will live in host countries or camps awaiting resettlement or other possible outcomes. UNHCR identifies three possible outcomes, referred to as durable solutions: resettlement in a country with a UNHCR resettlement programme, voluntary repatriation, or local integration (UNHCR, 2003). The reality is that the vast majority of these individuals spend many years waiting in these transitional contexts for such durable solutions to occur (Easton‐Calabria & Omata, 2018).

Research has consistently reported elevated rates of mental health problems among adult refugees. For example, an average prevalence rate of 30.6% for post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and 30.8% for major depression was found in a meta‐analysis of 161 articles (Steel et al., 2009). A great deal of research has examined risk factors and challenges associated with the pre‐migration, transit, and post‐migration stages that place refugees and asylum seekers at increased risk of mental health and psychosocial problems. Exposure to pre‐migration torture and other traumatic experiences (such as forced separation from family, loss of loved ones, loss of status and home, and witnessing or experiencing physical and sexual violence), and a multitude of resettlement stressors are often reported as the greatest predictors of mental health problems among refugees and asylum seekers (Chung & Kagawa‐Singer, 1993; Schweitzer, Melville, Steel, & Lacherez, 2006; Steel et al., 2009). While the majority of studies have been conducted in the resettlement context and the emphasis is often on pre‐ and post‐migration factors, specific aspects related to living in transit have also been found to be associated with increased psychological distress (Khawaja, White, Schweitzer, & Greenslade, 2008). Whether living in refugee camps or in a host community, the transition phase is characterised by living in a state of limbo and uncertainty. Many refugees in transit experience harsh living conditions, difficulty in meeting basic needs, low nutrition and poor health, loss of and separation from family and social networks, an inability to engage in education or employment, instability and fear for the future, fear of deportation, reduced or no access to healthcare including formal psychological services and treatment, and hostility, racism and violence from the host community or those co‐residing in refugee camps (Giacco, Laxhman, & Priebe, 2017; Khawaja et al., 2008; Shakespeare‐Finch & Wickham, 2010).

These stressors associated with the transition phase are likely to compound pre‐existing vulnerabilities associated with pre‐migration trauma and forced upheaval and consequently, place refugees and asylum seekers at great risk of developing mental health problems. Prolonged displacement in particular has been reported to be associated with decreases in resilience and increases in certain mental health problems such as depression (Bogic, Njoku, & Priebe, 2015; Chung & Kagawa‐Singer, 1993; Schweitzer et al., 2006).

While an abundance of literature identifies risk factors for and estimates the prevalence of mental health and psychosocial problems, many of these risk factors may not be readily amenable to change, particularly in the context of flight, transit, and uncertainty. Further, enablers of psychological well‐being among refugees and asylum seekers living in the transitional phase have received less attention. Quality peer‐reviewed evidence regarding effective enablers of psychological well‐being in transitional contexts remains limited. Enablers of psychological well‐being are conceptualised here as factors that could potentially be introduced or promoted in these contexts that may serve to buffer against adversity related to the refugee experience and ongoing difficulty associated with in living in exile.

The aim of this paper was to systematically review and synthesise the existing, international literature regarding enablers of psychological well‐being among refugees and asylum seekers in transit contexts, that is, living in host countries and for whom migration status is not final. This information will have important implications for the role of psychosocial support programmes in these contexts in terms of the appropriate focus of resource allocation, interventions and psychosocial support work.

In considering psychological well‐being as the outcome variable of focus, we were interested in synthesising research with any measure or discussion of psychological well‐being, mental health and other psychological constructs. This included consideration of distress, resilience, self‐esteem, quality of life, and mental health problems including symptoms of depression, post‐traumatic stress and anxiety. Because enablers to well‐being are likely to be different for children or young adolescents, the population of interest was adult, defined here as aged 16 years and above. Transitional contexts were defined as those in which the participants did not possess legal residency status nor were they residing in host countries which offered a standard UNHCR resettlement programme, that is, the host country was not listed as one of the 37 UNHCR resettlements countries as of 2016 (UNHCR, 2016).

2. METHODS

This systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines, which outline the preferred reporting for systematic reviews, in an effort to improve the quality of research used for decision‐making in service provision (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009).

2.1. Search strategy and information sources

The search strategy was developed by the research team in consultation with an academic librarian. The search was conducted in February 2018 in the following nine databases: Academic Search Premier, CINAHL, Embase, Emcare, Medline, Psychology and Behavioral Science, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search strategy included variations of the terms refugee/asylum seeker, enablers, and psychological well‐being, based on similar previous reviews and literature searches. The search strategy included a search for articles published from 1998 to 2018 (to ensure greater relevance to the current immigration context and refugee and asylum seeker experience). Where databases allowed, search terms were limited to titles, abstracts and keywords, and results were limited to English language, human participants, and adolescents and adults. An example of the search strategy can be found in Supporting Information Appendix S1. In addition, hand‐searching the reference lists of included articles was also conducted to seek additional results.

2.2. Study selection

A three‐stage screening and study selection process was followed: (a) MF and HE conducted a preliminary screen for any clearly irrelevant results (e.g. non‐peer reviewed journal articles); (b) remaining articles were subject to title and abstract screening by at least two reviewers (MF, MP, HE); (c) retained articles were subject to full‐text screening, by two reviewers (MP, HE). The final two stages were conducted in Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, 2018), an online software program that enables creation and management of systematic reviews. Due to the complexity of ascertaining the migration and legal status of participants, as well as whether the host country offered a UNHCR resettlement programme, the research team was often required to discuss and research these details before making a decision on an article. Because of this complication and the intricacies of our inclusion and exclusion criteria, the rate of inter‐rater agreement was not calculated for our screening process. However, any discrepancies of opinion during the final two stages were discussed among the team to achieve 100% agreement.

2.3. Eligibility criteria

Title and abstract, and full‐text screening involved applying the same eligibility criteria. Studies were considered eligible for inclusion if: the paper was a peer‐reviewed, primary research article (any study design, including qualitative and quantitative research) and conducted within the last 20 years; participants were first‐generation refugees/asylum seekers who were in a transit country, whose migration status was not final (to capture the experience of those who were still living in the uncertainty of a legal right to remain), and who were aged 16 years or older; the study explored any enablers of psychological well‐being. Studies were excluded if: they were not peer‐reviewed, nor primary research articles (e.g. magazines, newspaper articles, editorials, reviews, opinion pieces, study protocols, etc.); participants were not first‐generation refugees/asylum seekers whose migration status was not final, were in a country with a UNHCR resettlement programme, or were aged younger than 16 years (e.g. studies of children under the age of 16 years; studies of health professionals/teachers/volunteers working in this field; studies of the general public); if the study was a clinical intervention evaluation study (to ensure greater applicability of findings to contexts without resources to deliver clinical interventions e.g. randomised controlled trials or evaluations of therapeutic interventions delivered by a clinician); the study did not explore enablers of psychological well‐being (e.g. studies of the prevalence of mental illness, risk factors of/barriers to psychological well‐being, etc.).

2.4. Data collection process

A structured data table was used to extract information from each study; this was conducted and cross‐checked by two authors (MP and HE). Key information extracted included: objective, study design, participants, setting, main outcome measures, results, conclusions, strengths, and limitations.

2.5. Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias assessments were also conducted by two authors independently (MP and HE) and any discrepancies of opinion were resolved by discussion to gain 100% consensus (Supporting Information Appendix S2). Due to the variations in study designs included in this review, two separate appraisal tools were used to assess risk of bias: the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP, 2018) for qualitative studies, and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies (Moola et al., 2017). In the CASP checklist, criteria were assessed requiring a response out of three possibilities (i.e. Yes, Cannot Tell, or No) with the total number of yes responses giving a maximum score of 10 and indicating the highest methodological quality. The Checklist for Analytical Cross‐Sectional Studies required a response from four possibilities (i.e. Yes, No, Unclear or N/A) with a maximum score of eight. The research team agreed on the following scores: 100% high quality; 80%–90% moderate to high quality; 60%–70% moderate status. It was decided by consensus among the authors that if any paper scored lower than 50%, it would be excluded at the time of critical appraisal.

2.6. Synthesis of results

Due to the diversity across studies (in relation to settings, samples, methods, measures, data analysis, outcomes, and emphasis on enablers), qualitative and quantitative results have been synthesised in a narrative summary of findings. A thematic synthesis method was used whereby the authors coded the relevant, extracted text in order to identify descriptive themes (Snilstveit, Oliver, & Vojtkova, 2012; Thomas & Harden, 2008). These themes were counted and the frequency of each theme was determined to identify common findings. The descriptive themes were then collapsed into categories or analytical themes through discussion with the research team, where there was consensus regarding the final key categories of enablers chosen and reported (Snilstveit et al., 2012; Thomas & Harden, 2008). As enablers to psychological well‐being were not always the key or the sole focus of the research, articles which included an aspect of the research that identified enablers were included in this review; however, components or findings that did not relate to enablers of well‐being (e.g. prevalence of mental disorder) were not extracted and do not form part of this review.

3. RESULTS

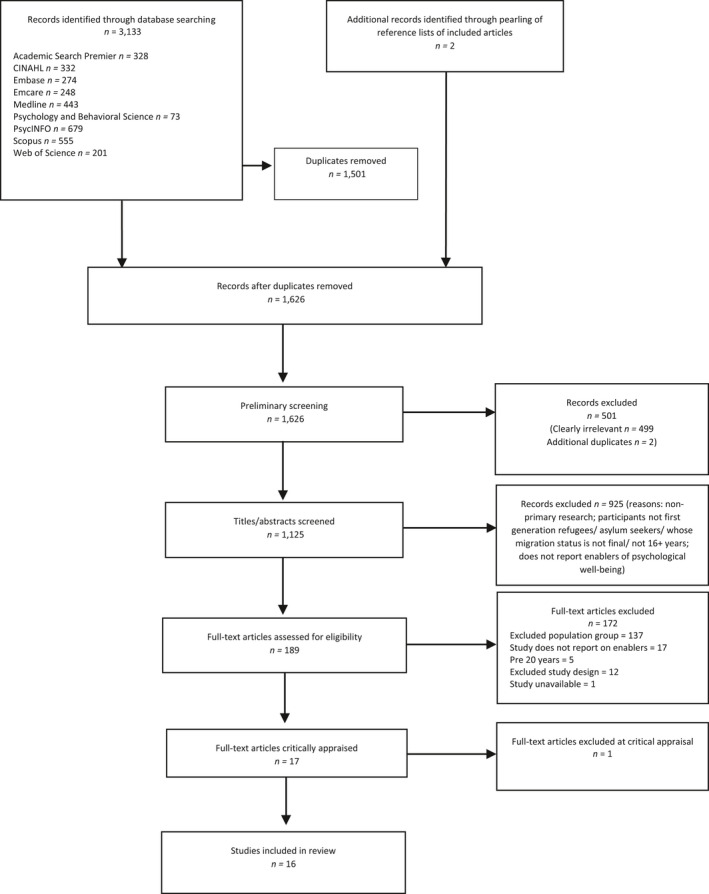

Initial database searching yielded 3,133 results. A further two records were included after scanning of reference lists (3,135). 1,501 duplicates were removed leaving a total of 1,626 results. A preliminary screen removed an additional 501 results that were clearly not relevant to the research topic (n = 499) or duplicates (n = 2) that had not been removed during the deduplication process. 1,125 titles and abstracts were screened during the next phase where 925 articles were excluded due to article type, incorrect population of interest, or incorrect outcomes of interest. This stage was followed by the full‐text screening of 189 articles where a further 172 full‐text articles were excluded at this stage. See Figure 1 for an outline of the screening process, including reasons for exclusion during title/abstract and full‐text screening. After the critical appraisal process, one paper was excluded (Jabbar & Zaza, 2016) due to the score from the CASP checklist being of low methodological quality and therefore the risk of bias being high CASP (2018). A total of 16 articles were deemed eligible for inclusion in this review.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of screening process and reasons for exclusion

3.1. Study characteristics

Characteristics of the 16 included studies1 are outlined in Table 1. Studies were published between 2002 and 2018. Four were quantitative cross sectional designs (Chase, Welton‐Mitchell, & Bhattarai, 2013; Emmelkamp, Komproe, Van Ommeren, & Schagen, 2002; Nakash, Nagar, Shoshani, & Lurie, 2017; Segal, Khoury, Salah, & Ghannam, 2018), 10 were qualitative studies (Akinyemi, Owoaje, & Cadmus, 2016; Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Cohen & Asgary, 2016; Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009; Hussain & Bhushan, 2011; Khawaja et al., 2008; Labys, Dreyer, & Burns, 2017; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Pavlish, 2005; Tippens, 2017) and two were mixed methods studies. From the mixed methods studies only the qualitative data were extracted for this review due to the quantitative components focusing solely on barriers (Chemali, Borba, Johnson, Khair, & Fricchione, 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004).

Table 1.

Overview of studies included in this review (n = 16)

| Study | Design | Setting | Participants | Measures | Findings regarding enablers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chase et al., 2013 | Quantitative ‐ Cross‐sectional Survey | Eastern Nepal (Refugee camps) |

n = 193 Age: 18–59 (83%) 60+ (16%) M = 46%; F = 54% Bhutanese. Buddhist 26%, Hindu 50%, Kirat 14%, Christian 7% Random sampling |

Brief COPE‐ modified version. |

The five factor solution (highly related coping strategies):

|

| Emmelkamp et al., 2002 | Quantitative ‐ Cross‐sectional Survey |

Nepal2 (Refugee camps) 1997 |

n = 315 Mean age = 44 years. M = 84% F = 16% Bhutanese. Random sampling |

|

Increases in received social support (but not perceived social support) were associated with reduction of depressive symptoms. |

| Nakash et al., 2017 |

Quantitative ‐ Cross‐sectional Survey |

Tel‐Aviv, Israel (Community) April 2012–June 2013 |

n = 90 M = 100% (male only sample) Age 19–48 Median age = 32 Eritrean and Sudanese. Convenience sampling |

|

|

| Segal et al., 2018 | Quantitative ‐ Cross‐sectional Survey via interview |

Lebanon (Shatila Refugee Camp) June 2012 ‐ June 2013 |

n = 254 M = 101 F = 107 63.4% Palestinian 18.5% Syrian 18.1% non‐refugee3 People lived in camp for average 21.1 years (±17) Convenience sampling |

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) |

|

| Study | Design | Setting | Participants | Interview or FG Focus | Findings regarding enablers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akinyemi et al., 2016 | Qualitative FG |

Ogun State, Nigeria (Oru Refugee Camp) 2010 |

n = 32 (4 FGs) M = 16 F = 16 Age 18–67; Mean age = 40.2 (±13.4). Liberian and Sierra Leonean. Purposive sampling |

|

|

| Chase & Sapkota, 2017 |

Qualitative Interview and FG |

Eastern Nepal (Refugee camp) August 2011 –June 2012 |

n = 40 for interviews n = 40 for FGs (4 FG approx. 10 in each)4 Age 18+ Bhutanese. Purposive sampling of community leaders and random sampling of other participants. |

|

|

| Chemali et al., 2017 |

Qualitative Interview |

Lebanon (Refugee camps in El‐Marj and Bar Elias) December 2015 |

n = 66 Age 65+ (average age was 65.88, ±7.26 years) M = 27 (40.9%) F = 39 (59.1%) Syrian. Convenience sample |

|

|

| Cohen & Asgary, 2016 | Qualitative FG | Thailand (Community) 2014 |

n = 49 (across 10 FGs) M = 13 F = 36 18+ Karen Burmese. Convenience sampling |

|

|

| Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009 | Qualitative Interview | Dharamsala, India (Community) 1998–2000 |

STUDY 1 n = 102 M = 66 F = 36 STUDY 2 n = 32 M = 26 F = 6 Tibetan refugee torture survivors. Convenience sampling |

|

STUDY 1: Most frequent/commonly reported: 1. Political coping, 2. Buddhist coping, 3. Spiritual attitude, 4. Positive thinking 5. Networking, 6. Social support. STUDY 2: a) Generally most helpful: 1. Political coping, 2. Spiritual coping, 3. Buddhist attitude, 4. Positive thinking, 5. Networking, 6. Social support (b) Counselling, most helpful: Buddhist attitude, Positive thinking, Networking, Social support, Psychotherapeutic help. |

| Hussain & Bhushan, 2011 | Qualitative interview | Himachal Pradesh, India (Community) |

n = 12 M = 8 F = 4 Age 25–46. Mean age =35 (SD=6.5) Tibetan. Snowball sampling |

Life history, challenging life experiences, how they coped with these challenges, and what Tibetan cultural resources were helpful in dealing with their traumatic experiences. |

Cultural resources:

|

| Khawaja et al., 2008 | Qualitative interview |

Brisbane, Australia Retrospective focus of time in transit countries: Egypt (community) & Kenya (camps) |

n = 23 M = 11 F = 12 Age 27–47 Mean age = 35 n = 22 Christian n = 1 Muslim Sudanese. Snowball sampling |

Life in Sudan prior to migration, experience in transit including coping strategies employed (focus of present review data extraction), and life in Australia after migration. |

|

| Labys et al., 2017 | Qualitative interview |

Durbin, South Africa (Community) October–December 2014 |

n = 18 M = 9 F = 9 Age 18–58 Mean age = 35.9 Zimbabwean and Congolese from DRC. Random sampling |

Problems, effects of problems, coping strategies and believed causes of problems, daily functioning | Coping strategies: talking with friends and refugee peers, attending church, praying, work, physical activities, interactions with family, and learning to speak Zulu (host country language). ‐Cognitive mechanisms: avoidance of thoughts, going to church, being active and focussing on family. ‐Social support: social contact, improving mood, sharing burdens, generating solutions, and assisting with finances. Connecting with people on social media for ideas about how to cope. ‐Physical activities and language: playing sport, dancing. |

| Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017 | Qualitative interview | Israel (Holot Detention Center) |

n = 8 M = 100% (male only sample) Age 27–38 Sudanese. Purposive sampling |

Experiences in Sudan and during the journey, experiences in Israel, relationships with Israelis and with Israeli society, relationships with relatives and other refugees, community engagement and support, factors contributing to adaptation and deterioration in their new environment, and perspectives regarding their future. |

|

| M uhwezi & Sam, 2004 | Qualitative5 Interview |

Kampala, Uganda (Community) Mean length of time living in Kampala = 47.6 months, (SD = 16.5) |

n = 9 M = 7 F = 2 Mean age=31 (of larger sample) Congolese, Somali, Kenyan, Rwandan. Purposive sampling. |

Friendship networks, financial situation, hospitality of Ugandans, social support, pre‐exile circumstances |

Social support for urban refugees either from fellow refugees, extended families, residential ethnic enclaves, friends or concerned natives seemed to strongly buffer stress and facilitate adaptation. Maintaining cultural identity. ‐Religion‐ provides hope, encourages forgiveness and helps with coping. –Employment. ‐Hospitality from native Ugandans to refugees. Learning the Ugandan language enhanced satisfaction and well‐being. |

| Pavlish, 2005 |

Qualitative interview (two part interview) Interpretive narrative approach |

Rwanda (Refugee camp) |

n = 14 F = 100% Age 18–50 Congolese. Purposive sampling |

Interview part 1: Describe memories and anecdotes about significant events and people past and present, stories about their ordinary days. Given the freedom to choose their own topics and anecdotes. Interview part 2: Initial interview topics were reviewed and additional anecdotes about those topics added. Three questions were then asked: (a) Can you describe experiences that make you fearful or feel unsafe? (b) Can you describe experiences when you have been strong? (c) Can you describe what you hope to experience in the future? |

Action Response 1: Refiguration‐ reframing, finding meaning and purpose from adverse experiences, economic activities. Action Response 2: Advocacy‐ agency, leads to hope, change situation. Action Response 3: Resistance‐ with family responsibilities at centre. Action Response 4: Resignation (not an enabler). Action Response 5: Sorrow (not an enabler). Action Response 6: Faith‐prayer, gaining strength and companionship from God. |

| Tippens, 2017 | Qualitative interview |

Nairobi, Kenya January–August 2014 (Community) |

n = 55; M = 27 F = 28 Age 17–70. Mean age = 38 Congolese from DRC. Purposive sampling |

|

|

Note. FG: focus group; F: female; M: male; DRC: democratic republic of congo.

Studies were conducted in various (n = 11) host countries including three studies in Nepal (Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Chase et al., 2013; Emmelkamp et al., 2002) (Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Chase et al., 2013; Emmelkamp et al., 2002), two in Lebanon (Chemali et al., 2017; Segal et al., 2018), two in India (Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009; Hussain & Bhushan, 2011), and two in Israel (Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Nakash et al., 2017). Studies were also conducted in Nigeria (Akinyemi et al., 2016), Thailand (Cohen & Asgary, 2016), Australia (retrospectively focused on coping during transit period in other host countries) (Khawaja et al., 2008), South Africa (Labys et al., 2017), Uganda (Muhwezi & Sam, 2004), Rwanda (Pavlish, 2005), and Kenya (Tippens, 2017).

Collectively, the studies reported sample sizes ranging from 8 to 315 participants with 1,352 total participants. The sample sizes of the quantitative studies ranged from 90 to 315 participants, with a total of 852 participants and a mean number of 213. Qualitative study sample sizes ranged from 8 to 102, with total of 500 participants and a mean number of 41.7. Two of the quantitative studies used random sampling (Chase et al., 2013; Emmelkamp et al., 2002) and two used convenience sampling (Nakash et al., 2017; Segal et al., 2018). The qualitative studies used a variety of participant sampling methods. Four studies used purposive sampling (Akinyemi et al., 2016; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004; Pavlish, 2005); one study used random sampling of refugees attending a clinic (Labys et al., 2017); three used convenience sampling (Chemali et al., 2017; Cohen & Asgary, 2016; Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009); three used snowball sampling (Hussain & Bhushan, 2011; Khawaja et al., 2008; Tippens, 2017); and one study used a combination of both random and purposive sampling (Chase & Sapkota, 2017).

Nine studies reported participants’ age range. Ages ranged from 17–70 years. Other studies simply reported that participants were above a certain age, for example, two studies reported participants were 18 years and over (Cohen & Asgary, 2016; Segal et al., 2018). One study did not report on age but it is clear from the outcomes that participants were adults (Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009), whereas one study reported a median age only (Chase & Sapkota, 2017). Four studies reported an average age, ranging from 31 to 65.88 years (Chemali et al., 2017; Emmelkamp et al., 2002; Labys et al., 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004). Chemali et al. (2017) specifically recruited elders aged 65 years and older.

Participants came from various cultural backgrounds or countries of origin (n = 15). Countries of origin included Bhutan (Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Chase et al., 2013; Emmelkamp et al., 2002); Eritrea (Nakash et al., 2017); Palestine (Segal et al., 2018), Syria (Chemali et al., 2017; Segal et al., 2018); Liberia (Akinyemi et al., 2016), Sierra Leone (Akinyemi et al., 2016); Myanmar/Burma (Cohen & Asgary, 2016); Tibet (Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009; Hussain & Bhushan, 2011); Sudan (Khawaja et al., 2008; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004; Nakash et al., 2017); Zimbabwe (Labys et al., 2017), Somalia, Rwanda, Ethiopia, and Kenya (Muhwezi & Sam, 2004); and the Democratic Republic of Congo (Labys et al., 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004; Pavlish, 2005; Tippens, 2017).

Eight studies reported that their participant groups were living in refugee camps (Akinyemi et al., 2016; Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Chase et al., 2013; Chemali et al., 2017; Emmelkamp et al., 2002; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Pavlish, 2005; Segal et al., 2018) and seven participant groups were living in the community of the transit country (Cohen & Asgary, 2016; Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009; Hussain & Bhushan, 2011; Labys et al., 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004; Nakash et al., 2017; Tippens, 2017). Khawaja et al. (2008) reported on Sudanese refugees who had lived in transit either in the community in Egypt or in refugee camps in Kenya.

One study did not specify percentages or numbers of participants that identified as male or female (Chase & Sapkota, 2017) and referred to a previous research paper for participant demographics (Chase & Sapkota, 2017). However, from the reporting in this article, it is clear that both male and female participants were represented. Overall, two studies reported percentages only, for male and female participants (Chase et al., 2013; Emmelkamp et al., 2002); two studies reported male participants only (Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Nakash et al., 2017); and one study reported female participants only (Pavlish, 2005); 10 studies reported numbers of both male and female participants (Akinyemi et al., 2016; Chemali et al., 2017; Cohen & Asgary, 2016; Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009; Hussain & Bhushan, 2011; Khawaja et al., 2008; Labys et al., 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004; Segal et al., 2018; Tippens, 2017).

The majority of participants across studies were male. Of the 13 studies that reported numbers of male and female participants, collectively, there were 409 (57%) male and 309 (43%) female participants (total n = 718). Two studies only reported percentages of male and female participants‐ of these, 65% were male and 35% were female (Chase et al., 2013; Emmelkamp et al., 2002). Taken together, the population sample of this systematic review consisted of approximately 61% male and 39% female participants.

Participant response rates were only reported in four studies. One study reported a 100% response rate (Khawaja et al., 2008), while another reported that 20% of those approached declined to participate (Nakash et al., 2017). One study reported that 11% (4/36) did not participate (Muhwezi & Sam, 2004), and another reported 13% (2/15) did not participate or complete the interview (Pavlish, 2005).

Of the studies for which we focused on the qualitative data, one study used both interviews and focus groups (Chase & Sapkota, 2017); two studies used focus groups only (Akinyemi et al., 2016; Cohen & Asgary, 2016); and nine studies used interviews only (Chemali et al., 2017; Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009; Hussain & Bhushan, 2011; Khawaja et al., 2008; Labys et al., 2017; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004; Pavlish, 2005; Tippens, 2017). As stated earlier, only the qualitative aspect and data for two studies (Chemali et al., 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004) were included as the quantitative data addressed barriers and not enablers.

Of the four cross sectional studies, 12 validated measures were used (excluding the social demographic tool in Nakash et al. (2017) because it was a simple demographic questionnaire). Due to the focus of our review, data were extracted relating to only six of these measures. Two measures were used to clarify broad mental illness: (Symptom Checklist‐90‐Revised—SCL‐90, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale—K6), two measures were used to ascertain PTSD status (Harvard Trauma Questionnaire‐Part 1—HTQ‐1, PTSD Checklist Civilian Version—PCL), one measure assessed coping (Brief COPE), and two measures examined social support (Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support—MSPSS, Social Network Schedule—SNS).

3.2. Risk of bias within and across studies

Two of the four cross sectional studies scored high in methodological quality and therefore low risk of bias (Nakash et al., 2017; Segal et al., 2018); one study scored moderate to high quality (Emmelkamp et al., 2002) due to not addressing strategies for confounding factors. One study scored moderately (Chase et al., 2013) due to participant inclusion criteria omissions and not addressing confounding factors.

Two of the qualitative studies scored high in methodological quality (Pavlish, 2005; Tippens, 2017) addressing all of the criteria of the critical appraisal tool. Six studies scored moderate to high, addressing all of the criteria of the critical appraisal tool with the exception of consideration of the relationship between researcher and participant (Akinyemi et al., 2016; Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Chemali et al., 2017; Cohen & Asgary, 2016; Labys et al., 2017; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017). Two of these studies did not report on consideration of ethical issues, yet still scored moderate to high quality (Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009; Khawaja et al., 2008). The remaining two qualitative studies scored moderately (Hussain & Bhushan, 2011; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004) due to not reporting on aspects such as the relationship between the researcher and participants, consideration of ethical issues, and due to the opinion that data analysis was not sufficiently rigorous as researchers did not consider their own role, potential bias and influence during analysis of qualitative data.

3.3. Key enablers

Results from the included four quantitative studies (Chase et al., 2013; Emmelkamp et al., 2002; Nakash et al., 2017; Segal et al., 2018) and 12 qualitative studies (Akinyemi et al., 2016; Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Chemali et al., 2017; Cohen & Asgary, 2016; Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009; Hussain & Bhushan, 2011; Khawaja et al., 2008; Labys et al., 2017; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004; Pavlish, 2005; Tippens, 2017) are summarised in Table 1 and discussed here according to the key categories of enablers identified by the studies. The findings from the quantitative and qualitative data are summarised together due to overlap in the findings.

3.3.1. Social support

The protective effects of social support for psychological well‐being and adaptation were reported in 11 studies (Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Chase et al., 2013; Chemali et al., 2017; Cohen & Asgary, 2016; Emmelkamp et al., 2002; Khawaja et al., 2008; Labys et al., 2017; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004; Nakash et al., 2017; Tippens, 2017). Social support networks included community, family, friends, fellow refugees, church or religious groups, elders, neighbours, and locals/members of the host community. Support was in the form of emotional, practical, financial, and engagement in or encouragement of social activities. Emotional support referred to the sharing of burdens, sharing of ideas on how to cope better, encouraging engagement in other (adaptive) behaviours, and storytelling. Practical and material support from social networks involved family, friends and community members assisting each other with cooking, cleaning, finances, resources, and other practical needs, particularly if someone was experiencing emotional difficulties preventing them from engaging in these tasks (Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Khawaja et al., 2008; Labys et al., 2017; Tippens, 2017).One study of Syrian elders living in a refugee camp in Lebanon reported that engaging in chores with family, and storytelling, was thought to foster a sense of normalcy (Chemali et al., 2017). Social activities were seen as an outlet for distraction and sharing, and were reported to be associated with improved mood (Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Cohen & Asgary, 2016; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004). Social support was also reported to be important for safety and security (Chemali et al., 2017; Tippens, 2017), as well as preserving values of the culture, identity and belonging (Chemali et al., 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004).

Two quantitative studies examined received social support versus perceived social support, with contradictory results. Emmelkamp et al. (2002) found that received social support (but not perceived social support) related to well‐being for Bhutanese refugees and in particular, was associated with reduced depression; however, Nakash et al. (2017) found that perceived social support was protective and associated with lower risk of developing posttraumatic stress symptoms for Eritrean and Sudanese male refugees who had been exposed to low levels of trauma (but not high levels of trauma).

3.3.2. Faith, religion, spirituality, and culture

Eleven studies reported aspects related to faith, religion, spirituality, and culture to be important for well‐being (Akinyemi et al., 2016; Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Chase et al., 2013; Cohen & Asgary, 2016; Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009; Hussain & Bhushan, 2011; Khawaja et al., 2008; Labys et al., 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004; Pavlish, 2005; Tippens, 2017). Having faith in God's plan, feeling comfort, peace, and strength from God, consulting with or gaining strength from religious leaders and figures such as the Dalai Lama, and engaging in religious rituals and in prayer were reported to alleviate emotional stress and help people cope. Engaging in religious activities was also reported to lead to a sense of normalcy in the current situation (Tippens, 2017). Cultural resources such as historical exemplars of strength, religious teachings or Buddhist philosophy, and culturally condoned coping strategies such as meditation or worship were reported as important for psychological well‐being (Chase et al., 2013; Hussain & Bhushan, 2011).

Religion was often linked to social networks as refugees reported praying for each other, trusting religious community, and identifying the religious community as important for material and social support (Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Khawaja et al., 2008; Tippens, 2017). It should be noted that one study found that religion was less important and less protective for younger refugees, compared with elders in their research but did not state what ages they were referring to (Cohen & Asgary, 2016).

3.3.3. Cognitive strategies

Nine studies reported on cognitive strategies employed by participants to enhance psychological well‐being (Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Chase et al., 2013; Cohen & Asgary, 2016; Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009; Hussain & Bhushan, 2011; Khawaja et al., 2008; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Pavlish, 2005; Tippens, 2017). Beneficial cognitive strategies that were identified in the studies included reframing, self‐reflection, acceptance, positive thinking, problem‐solving, distraction techniques (in order to avoid unhelpful or traumatic thoughts/memories), and identification of hopes, wishes and future aspirations and intentionally focusing on them. Cognitive strategies which involved making comparisons included intentionally comparing the present with the past and the situation they fled from, as well as comparing their story to other events in history (Labys et al., 2017; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Tippens, 2017). One study reported participants compartmentalised past and present and managed their memories by creating and dedicating specific spaces and times to remembering (Tippens, 2017).

Creating an internal narrative that focuses on their survival story, making sense of their experiences, and finding meaning in their suffering, which ultimately resulted in a restoration of personal meaning, were higher level cognitive strategies associated with enhanced well‐being (Hussain & Bhushan, 2011; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Pavlish, 2005).

Three studies reported that participants found it helpful to reframe or find an alternative way to view the situation, or focus on a sense of purpose and meaning that their experience had now given them (Chase et al., 2013; Khawaja et al., 2008; Pavlish, 2005). Examples of this included normalising or minimising the severity of their situation, comparison strategies mentioned earlier, or focusing a potentially positive outcome of a negative experience such as focusing on the arrival of a baby rather than on the rape that led to the pregnancy, or contracting HIV and reframing this situation as an opportunity to become an advocate and educate others about HIV and safe sex.

The problem‐solving cognitive strategies were reported to also occur in the context of social support when social networks assisted with trying to find solutions, or offering reassurance and encouragement to reframe and change unhelpful thoughts and behaviours. Focusing thoughts on family and friends, relationships, and family reunification was another cognitive strategy linked with social support. The use of humour and laughter was only reported as an enabler for well‐being by participants in two studies (Chase et al., 2013; Tippens, 2017).

3.3.4. Engaging in employment and economic activities

Overall, six studies reported that working and participating in activities to increase economic standing facilitated psychological well‐being (Labys et al., 2017; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004; Pavlish, 2005; Segal et al., 2018; Tippens, 2017). Four studies reported that employment opportunities were important for well‐being (Labys et al., 2017; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004; Segal et al., 2018). Qualitative findings suggested that employment was not only important for financial reasons, but also for self‐identity, hope for the future, distraction and managing mental health (Labys et al., 2017; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004). In the quantitative study, Segal et al. (2018) found that access to paid employment reduced the risk of Syrian refugees in Lebanon experiencing a serious mental illness by 66%. Engaging in other activities with the aim of increasing economic standing such as bartering, using aid to purchase goods to re‐sell for a profit, and using borrowing systems to create opportunities for financial growth were reported to be related to well‐being in two studies (Pavlish, 2005; Tippens, 2017).

3.3.5. Education and vocational training

The protective effects of education and vocational training were reported in five studies (Akinyemi et al., 2016; Cohen & Asgary, 2016; Labys et al., 2017; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004). Reading, studying, education and acquiring vocational skills were related to self‐improvement, improved self‐help and agency, and hope for the future. Education and training was found to be important for self‐esteem and strengthening their inner narrative (Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017).

Two studies reported that learning the language of the host country contributed to well‐being (Labys et al., 2017; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004). Learning the host language was reported to have an impact on how the locals of the host society interacted with the refugees which in turn, was reported to also enhance well‐being, given that the attitude of locals (and violence perpetrated by locals) was reported to contribute to emotional stress for refugees during the transit period.

3.3.6. Behavioural strategies

Distraction behaviours, ‘keeping the mind busy’, and behavioural strategies to enhance mood were coping strategies reported in four studies (Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Chase et al., 2013; Labys et al., 2017; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017). Physical activity, keeping involved in games, sports, hobbies, listening to music, watching movies and TV, going to church, as well as working and learning were commonly reported behavioural strategies that served either a distraction or mood improvement purpose (Chase & Sapkota, 2017; Chase et al., 2013; Labys et al., 2017; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017).

3.3.7. Advocacy and activism

Political coping and engagement, social and political activism, and resistance and advocacy were reported in three studies to be enablers of well‐being (Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Pavlish, 2005). The beneficial aspects of such activities were related to redefining their identity as a hero rather than a victim, increasing their sense of agency or hope for future, and taking a stand against perceived injustice (Elsass & Phuntsok, 2009; Lavie‐Ajayi & Slonim‐Nevo, 2017; Pavlish, 2005). These strategies were related to cognitive strategies regarding finding a sense of meaning and purpose in their situation and life.

3.3.8. Environment

Housing conditions were mentioned in three studies as being important for mental health status and quality of life (Akinyemi et al., 2016; Muhwezi & Sam, 2004; Segal et al., 2018). Stable secure housing was a commonly mentioned enabler across four focus groups in a qualitative study of West African refugees living in Nigeria (Akinyemi et al., 2016). Living in closer residential enclaves was reported to foster social support, which in turn was reported to be essential for positive adaptation to the transit environment (Muhwezi & Sam, 2004). Similarly, a quantitative study found that stable housing and living conditions accounted for a 79% decrease in risk of serious mental illness among Palestinian refugees living in Lebanon (Segal et al., 2018).

4. DISCUSSION

This paper examined enablers of psychological well‐being among refugees and asylum seekers in host countries/transit contexts and for whom migration status was not finally determined. Social support and religious/cultural/spirituality related factors were the most commonly reported enablers of well‐being, followed by cognitive strategies, engaging in employment and economic activities, engaging in education and training, behavioural strategies, advocacy and activism, and environment/housing. Despite these reviewed studies being set in diverse and varied contexts, across a number of countries, and with participants of diverse cultural backgrounds and diverse refugee experiences, the findings across studies were relatively consistent. Of note was the interrelated nature of the enablers. Overall, three critical themes emerged: social, religious and cultural strengths and resources; future‐orientated mindset; and finding meaning and purpose in life, despite displacement.

Social connectedness—where people experience a sense of belonging and self‐accomplishment in the company of others—is a well‐established protective factor for mental health, argued to provide a buffering effect against psychological distress and certain mental disorders (Harandi, Taghinasab, & Nayeri, 2017; Maulik, Eaton, & Bradshaw, 2010), and particularly among individuals who have experienced adverse life events (Dalgard, Bj, & Tambs, 1995). Consistent with our findings, social support was listed as one of the most commonly reported coping strategies utilised by conflict affected individuals in a recent systematic review (Seguin & Roberts, 2017). This common emphasis on the importance of community and social networks for refugee psychological well‐being is consistent with the idea that refugee resilience encompasses a more communal notion of resilience than the Western, more individualised concept (Hutchinson & Dorsett, 2012).

Social, cultural, and religious enablers appeared to serve a multitude of practical and psychological functions for participants across studies, varying between individuals and serving different purposes at different times. Cultural and religious factors add an important dimension to social connectedness in that they facilitate a sense of belonging and are important for individual and collective cultural identity, key concepts underpinning psychological well‐being (Thoits, 2013). Further, in addition to social and religious enablers serving an internal, identity development function, engaging in social and religious activities were reported to provide some sense of normality to participants. This suggests that attempting to generate a state that feels normal, comfortable or predictable, as defined by the individual, may also be a strategy that some refugees adopt in order to cope with the stressors of their environment. Similarly, engaging in social, cultural, and religious activities were also reported to serve as a distraction or bring about a sense of life before displacement. Regardless of the function underlying these enablers, these ideas point to the importance of rebuilding community and creating opportunities for people to connect to their culture and faith, participate in social activities that are meaningful to them, meet practical and emotional needs and assist to create a sense of connectedness and belonging.

Enablers that facilitated connection to a sense of meaning, purpose and hope were repeatedly emphasised, and included employment, learning, self‐improvement, engaging in religious or spiritual activities, political advocacy, caring for family members (particularly children), and making sense of the past and present. Activities that helped the individual make sense of their experiences, such as religion or advocating for others, were of particular value. These activities also reflected both individual and cultural values and identity, and assisted individuals in working towards a future goal.

Related to this, enablers that were future‐orientated, whether they were cognitive or behavioural, were associated with enhanced well‐being. These included engaging in study and planning, maintaining aspirations and hope for the future, and looking forward to future reunification with family. Cognitive strategies such as restructuring, reframing, intentionally focusing on survival, and purposeful reflection by creating and dedicating specific spaces to remember were reported to generate hope for the future and feelings of meaning and purpose. Cognitive restructuring and problem‐solving were also commonly reported coping strategies across studies regarding conflict affected adults (Seguin & Roberts, 2017). It is noteworthy that such strategies may be of limited utility throughout protracted periods of limbo and uncertainty. Nevertheless, participants across the reviewed studies had been in transit for months to many years. Additionally, hope, optimism, meaning making, and planning for the future have been found to assist with refugee adaptation in the resettlement context and in processing traumatic experiences (Clarke & Borders, 2014). Shakespeare‐Finch and Wickham (2010) reported that future‐focused hopes and goals were important personal resources for resilience and adaptation among refugees in multiple stages of the refugee journey, particularly in transit and resettlement.

Psychosocial support interventions that facilitate identifying hopes, aspirations, and goals and incorporate a solution‐orientated, action‐orientated approach into conversations may help refugees attempt to utilise the transit period to develop skills, retain hope, and help them live a life that is as close as possible to the life that they would want to live, if they were not limited in this context. Intervention may also necessitate incorporating the strengths‐ and values‐based approach to assist in identifying what a meaningful and fulfilling life looks like for each individual, which for many would be a pre‐requisite to engage in a more action‐orientated approach, striving for, or achieving, meaning and purpose. Engaging in training, employment and other future orientated pursuits were also reported across studies to serve as distraction and so for those refugees and asylum seekers who may be less capable of focusing on the future, work and education enablers may serve more of a practical function than a meaningful and future‐focused one.

It is important to acknowledge the barriers that might exist that prevent an individual adopting these enablers or experiencing the benefit of them. In terms of connecting to a sense of meaning and purpose, making sense of current and past experiences, and adopting an action‐orientated, future‐focused mentality, although ideal, requires certain internal and external resources to enable these higher level cognitive and emotional processes. Labys et al. (2017) suggested that the absence of positive and forward‐thinking coping strategies may relate the high levels of hopelessness, helplessness, worthlessness, and suicidal ideation that they observed in their research among refugees in protracted transit. In a study of Tibetan refugees included in this review, Hussain and Bhushan (2011) acknowledged that making sense of refugee experiences such as torture, upheaval, and protracted displacement is a difficult and painful process that would not be possible without certain personal and cultural resources that enable this process to occur. A compassionate therapeutic approach would be sensitive to the understanding that not all refugees would have this capacity and that for some, this capacity would fluctuate over time, along with the function underlying different enablers or coping strategies.

Similarly, in relation to the positive effects of social support, the findings from Nakash et al. (2017) suggest that social support may be more of an enabler to well‐being for individuals who have been exposed to low levels of trauma rather than those who may be more at risk of or already experiencing post‐traumatic stress disorder. Further, the findings from Emmelkamp et al. (2002) suggest that social support may have more of an impact in relation to depressive symptoms. Therefore it is important to recognise that social support may be less effective for certain individuals or in reducing experiences of certain mental health problems and it is important for people providing psychosocial support to acknowledge the complex relationship between an individual's experiences, social support factors, and mental health.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

The strength of this review is that, to our knowledge, it is the first to collate and synthesise peer‐reviewed information regarding enablers of psychological well‐being in the specific transit context of individuals living in host countries with unresolved migration status. This is profoundly important given the high and increasing numbers of refugees and asylum seekers fleeing their home countries and residing in host societies while they await resettlement or other durable solutions. This review also employed rigorous methodology, following the PRISMA guidelines and using a thorough and comprehensive search strategy developed in collaboration with an academic librarian, to ensure full coverage of the literature. Further, the review process involved two reviewers for screening, data extraction and critical appraisal, enhancing the overall trustworthiness of the results. Despite these strengths, this review is not without limitations. Studies were excluded if the migration status of the participants was unclear or not reported. Therefore relevant studies may have potentially been excluded. It is possible that by focusing solely on enablers, we were biasing our attention to focus only on positive results and negating some of the complexity in which these enablers are located. As highlighted by the contradictory results between perceived social support versus received social support, there are additional aspects within these broad categories of identified enablers that were not possible to examine in this review, largely due to the majority of the limited international literature on this topic utilising qualitative methodology. Consequently, this review did not enable us to consider the complex interplay of factors that lead to enhanced psychological well‐being. Overall, the current evidence base is limited by these methodological factors. The cross‐sectional design of all the quantitative studies included in this review leads to difficulty in establishing causal relationships between the factors identified and well‐being. Further, the qualitative findings are based on self‐reported narratives and are subject to similar limitations across all the studies such as social desirability, under reporting, and relying heavily on memory. The evidence base would benefit from longitudinal studies across a range of settings and contexts to better understand factors that promote well‐being during transition and how this translates to mental health and psychosocial outcomes into the future, including if and when resettlement is achieved.

5. CONCLUSION

This review contributes to the knowledge base on enablers of psychological well‐being for refugees and asylum seekers in the flight/transition phase of the refugee journey. Forced migration necessitates the ability to know how and when to move in new ways and to adapt to and cope with traumatic pasts, an uncertain present, unexpected changes, and ongoing stressors. Understanding what enables individuals, who are without durable solutions, to cope better and engage in processes that promote more positive adaptation to the transit environment is imperative to enhance the psychological well‐being of refugees and asylum seekers in these contexts. Findings from this review suggest that programmes and resource allocation should be directed to areas that encourage or facilitate social support and opportunities for people to live a life that is as close as possible to what they foresee or aspire to, to expand and enrich social networks and connection to faith, facilitate future‐orientated focus such as participation in self‐improvement, training or employment opportunities, and assist individuals connect to a sense of meaning, purpose and hope by incorporating and strengthening adaptive cognitive strategies including helping people make sense of their experiences and current situation.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Carole Gibbs, Academic Librarian, University of South Australia for her guidance when developing the search strategy for this review.

Posselt M, Eaton H, Ferguson M, Keegan D, Procter N. Enablers of psychological well‐being for refugees and asylum seekers living in transitional countries: A systematic review. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27:808–823. 10.1111/hsc.12680

Funding information

Funding for this systematic review was provided by HOST International.

ENDNOTES

It should be noted that the two studies authored by Chase appear to be two components of the same research project. Because they were published separately with the 2013 article being quantitative and the 2017 qualitative, we report them separately.

Reporting on sample 1 only as sample 2 were Nepalese torture survivors not Bhutanese.

All groups reported separately, non‐refugees excluded from extraction.

Reported in Chase et al. 2013.

Reporting on qualitative data only for this study as per methodology.

REFERENCES

- Akinyemi, O. O. , Owoaje, E. T. , & Cadmus, E. O. (2016). In their own words: Mental health and quality of life of West African refugees in Nigeria. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 17(1), 273–287. 10.1007/s12134-014-0409-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bogic, M. , Njoku, A. , & Priebe, S. (2015). Long‐term mental health of war‐refugees: A systematic literature review. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 15(1), 808–41. 10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASP . (2018). Critical appraisal skills programme checklist: 10 questions to help you make sense of a Qualitative research. Retrieved from https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-Download.pdf

- Chase, L. , & Sapkota, R. P. (2017). "In our community, a friend is a psychologist": An ethnographic study of informal care in two Bhutanese refugee communities. Transcultural Psychiatry, 54(3), 400–422. 10.1177/1363461517703023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase, L. , Welton‐Mitchell, C. , & Bhattarai, S. (2013). “Solving Tension”: Coping among Bhutanese refugees in Nepal. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 9(2), 71–83. 10.1108/IJMHSC-05-2013-0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chemali, Z. , Borba, C. P. C. , Johnson, K. , Khair, S. , & Fricchione, G. L. (2017). Needs assessment with elder Syrian refugees in Lebanon: Implications for services and interventions. Global Public Health, 1–13, 10.1080/17441692.2017.1373838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, R. C. , & Kagawa‐Singer, M. (1993). Predictors of psychological distress among Southeast Asian refugees. Social Science & Medicine, 36(5), 631–639. 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90060-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, L. K. , & Borders, L. D. (2014). "You got to apply seriousness": A phenomenological inquiry of Liberian refugees' coping. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(3), 294–303. 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00157.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. , & Asgary, R. (2016). Community Coping Strategies in Response to Hardship and Human Rights Abuses Among Burmese Refugees and Migrants at the Thai‐Burmese Border A Qualitative Approach. Family & Community Health, 39(2), 75–81. 10.1097/fch.0000000000000096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgard, O. S. , Bj, S. , & Tambs, K. (1995). Social support, negative life events and mental health. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 166(1), 29–34. 10.1192/bjp.166.1.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton‐Calabria, E. , & Omata, N. (2018). Panacea for the refugee crisis? Rethinking the promotion of ‘self‐reliance’for refugees. Third World Quarterly, 808–17, 10.1080/01436597.2018.1458301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elsass, P. , & Phuntsok, K. (2009). Tibetans' coping mechanisms following torture: An interview study of Tibetan torture survivors' use of coping mechanisms and how these were supported by western counseling. Traumatology, 15(1), 3–10. 10.1177/1534765608325120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emmelkamp, J. , Komproe, I. H. , Van Ommeren, M. , & Schagen, S. (2002). The relation between coping, social support and psychological and somatic symptoms among torture survivors in Nepal. Psychological Medicine, 32(8), 1465–1470. 10.1017/S0033291702006499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacco, D. , Laxhman, N. , & Priebe, S. (2017). Prevalence of and risk factors for mental disorders in refugees. Paper presented at the Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Harandi, T. F. , Taghinasab, M. M. , & Nayeri, T. D. (2017). The correlation of social support with mental health: A meta‐analysis. Electronic Physician, 9(9), 5212 10.19082/5212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, D. , & Bhushan, B. (2011). Cultural factors promoting coping among Tibetan refugees: A qualitative investigation. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 14(6), 575–587. 10.1080/13674676.2010.497131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, M. , & Dorsett, P. (2012). What does the literature say about resilience in refugee people? Implications for practice. Journal of Social Inclusion, 3(2), 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbar, S. A. , & Zaza, H. I. (2016). Evaluating a vocational training programme for women refugees at the Zaatari camp in Jordan: Women empowerment: A journey and not an output. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 21(3), 304–319. 10.1080/02673843.2015.1077716 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khawaja, N. G. , White, K. M. , Schweitzer, R. , & Greenslade, J. (2008). Difficulties and coping strategies of sudanese refugees: A qualitative approach. Transcultural Psychiatry, 45(3), 489–512. 10.1177/1363461508094678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labys, C. A. , Dreyer, C. , & Burns, J. K. (2017). At zero and turning in circles: Refugee experiences and coping in Durban, South Africa. Transcultural Psychiatry, 54(5–6), 696–714. 10.1177/1363461517705570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie‐Ajayi, M. , & Slonim‐Nevo, V. (2017). A qualitative study of resilience among asylum seekers from Darfur in Israel. Qualitative Social Work, 16(6), 825–841. 10.1177/1473325016649256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maulik, P. K. , Eaton, W. W. , & Bradshaw, C. P. (2010). The effect of social networks and social support on common mental disorders following specific life events. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 122(2), 118–128. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01511.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moola, S. , Munn, Z. , Tufanaru, C. , Aromataris, E. , Sears, K. , Sfetcu, R. … Mu, P.‐F. (2017). Critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross sectional studies. Retrieved from https://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html

- Muhwezi, W. W. , & Sam, D. L. (2004). Adaptation of urban refugees in Uganda: A study of their socio‐cultural and psychological well being in Kampala City. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 14(1), 37–46. 10.4314/jpa.v14i1.30608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakash, O. , Nagar, M. , Shoshani, A. , & Lurie, I. (2017). The association between perceived social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms among Eritrean and Sudanese male asylum seekers in Israel. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health, 10(3), 261–275. 10.1080/17542863.2017.1299190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlish, C. (2005). Action responses of Congolese refugee women. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 37(1), 10–17. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00010.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, R. , Melville, F. , Steel, Z. , & Lacherez, P. (2006). Trauma, post‐migration living difficulties, and social support as predictors of psychological adjustment in resettled Sudanese refugees. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(2), 179–187. 10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01766.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal, S. P. , Khoury, V. C. , Salah, R. , & Ghannam, J. (2018). Contributors to screening positive for mental illness in Lebanon's Shatila Palestinian Refugee Camp. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 206(1), 46–51. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguin, M. , & Roberts, B. (2017). Coping strategies among conflict‐affected adults in low‐ and middle‐income countries: A systematic literature review. Global Public Health, 12(7), 811–829. 10.1080/17441692.2015.1107117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare‐Finch, J. , & Wickham, K. (2010). Adaptation of Sudanese refugees in an Australian context: Investigating helps and hindrances. International Migration, 48(1), 23–46. 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00561.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snilstveit, B. , Oliver, S. , & Vojtkova, M. (2012). Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 4(3), 409–429. 10.1080/19439342.2012.710641 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steel, Z. , Chey, T. , Silove, D. , Marnane, C. , Bryant, R. A. , & Van Ommeren, M. (2009). Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA, 302(5), 537–549. 10.1001/jama.2009.1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits, P. A. (2013). Self, identity, stress, and mental health In Aneshensel C. S. Phelan, J. C. & Bierman A. (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (Second ed., pp. 357–377). Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. , & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tippens, J. A. (2017). Urban Congolese refugees in Kenya: The contingencies of coping and resilience in a context marked by structural vulnerability. Qualitative Health Research, 27(7), 1091–1103. 10.1177/1049732316673342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR (2003). Framework for durable solutions for refugees and persons of concern. Geneva: Core Group on Durable Solutions. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR (2016). Information on UNHCR resettlement. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/en-au/information-on-unhcr-resettlement.html

- UNHCR (2018). Global trends: Forced displacement in 2017. Geneva: UNHCR. [Google Scholar]

- Veritas Health Innovation . (2018). Covidence systematic review software. Retrieved from www.covidence.org

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials