Abstract

Human skin graft mouse models are widely used to investigate and develop therapeutic strategies for the severe generalized form of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB), which is caused by biallelic null mutations in COL7A1 and the complete absence of type VII collagen (C7). Most therapeutic approaches are focused on reintroducing C7. Therefore, C7 and anchoring fibrils are widely used as readouts in therapeutic research with skin graft models. In this study, we investigated the expression pattern of human and murine C7 in a grafting model, in which human skin is reconstituted out of in vitro cultured keratinocytes and fibroblasts. The model revealed that murine C7 was deposited in both human healthy control and RDEB skin grafts. Moreover, we found that murine C7 is able to form anchoring fibrils in human grafts. Therefore, we advocate the use of human‐specific antibodies when assessing the reintroduction of C7 using RDEB skin graft mouse models.

Keywords: anchoring fibrils, dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, human skin grafting, Type VII collagen

1. BACKGROUND

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) is a monogenetic blistering skin disorder caused by mutations in the COL7A1 gene that encodes type VII collagen (C7). After post‐transcriptional modifications, C7 assembles into anchoring fibrils (AFs) which secure attachment of the lamina densa to the dermal matrix.[1] DEB is inherited either dominantly (DDEB; OMIM#131750) or recessively (RDEB; OMIM#226600).[2]

Currently, there is no cure for DEB, and, therefore, there is a need for animal models for therapy development. Existing animal models comprise several spontaneously developed models of DEB in cat, dog, sheep and rat, but these are not C7 null models.[3] Spontaneous C7 null animals do not survive beyond the neonatal phase, and therefore, conditional knockout and hypomorphic mouse models have been developed.[4,5] However, these models suffer from residual C7 expression. Moreover, more than 700 different COL7A1 variants have been identified in DEB causing a wide variety of phenotypes, and models only exist for a few COL7A1 mutations.[6,7] To circumvent these drawbacks, mouse models that tolerate human skin grafts are commonly used in DEB research, as they allow to directly test therapeutic approaches on patient skin and for specific mutations. Because the complete absence of C7 is the cause of disease in the generalized severe recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB‐gen sev) subtype, most therapeutic approaches are focussed on reintroducing C7 in patient skin. Expression of C7 and the presence of AFs in the grafts are therefore important readouts.

Because we noticed the presence of AFs in skin grafts generated out of human C7 null cells, we posed the question whether murine C7 is deposited at the basement membrane zone (BMZ) and could contribute to the formation of AFs seen in human skin grafts, which could seriously confound results obtained using such skin grafts.

2. QUESTIONS ADDRESSED

We examined the presence and source of murine C7 in reconstituted human skin grafts grown on the back of mice. Thereby, we answer the question as to how human C7 expression should be analysed validly in grafting models.

3. EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

In the grafting model, skin equivalents were reconstituted in vivo within grafting chambers implanted on the back of mice from a keratinocyte/fibroblast cell suspension (see Supplementary Methods for details).[8] The model is well established and has recently been used in the context of therapy development for RDEB.[9]

Control grafts were generated using healthy human control skin cells and RDEB grafts using C7 null RDEB patient‐derived skin cells (see Supplementary Methods for details). Biopsies were taken 10 weeks postgrafting and subjected to immunofluorescence C7 staining (IF) and ultrastructural imaging of AFs. The human‐specific monoclonal antibody LH7.2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and the mouse‐specific polyclonal antibody AP23437PU (Acris, Herford, Germany) were used as primary antibodies against C7. Electron microscopy was performed on glutaraldehyde‐fixed biopsies as previously described.[10] Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) using human X‐chromosome and Y‐chromosome probes (Abbott Molecular, Del Plaines, IL, USA) was used to distinguish human from murine cells.

4. RESULTS

IF using the LH7.2 antibody on control human and control murine skin confirmed specificity of LH7.2 for human C7; LH7.2 did not cross‐react with murine C7 (Figure S1). Similarly, IF using the polyclonal AP23437PU antibody on control human and control mouse skin confirmed that the antibody is specific for murine C7 and does not cross‐react with human C7.

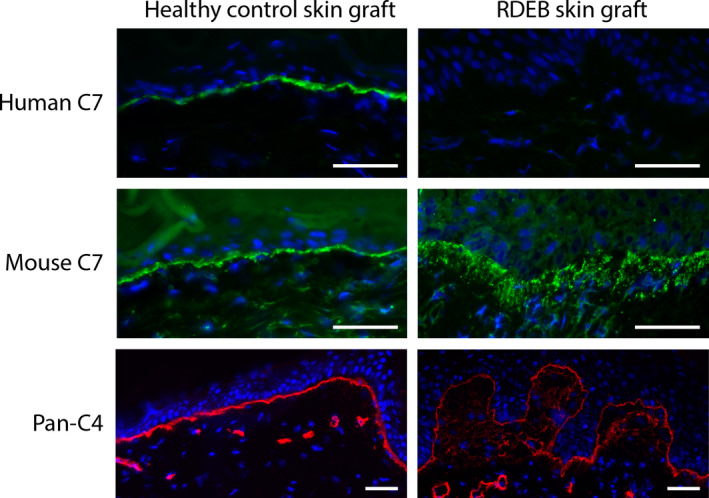

IF for human C7 (LH7.2) showed brightly positive staining along the BMZ in control skin grafts (Figure 1). RDEB skin grafts revealed the complete absence of human C7 staining, as expected. Surprisingly though, both control and RDEB skin grafts showed positive staining for murine C7 along the BMZ (Figure 1). In the RDEB skin grafts, the C7 deposition along the BMZ showed a widened pattern, which correlated with staining for type IV collagen (C4), which is the major component of the lamina densa. This widening has been noticed before in RDEB patient skin grafts.[9]

Figure 1.

Immunofluorescence staining reveals mouse type VII collagen deposition in skin grafts. Healthy control skin graft and RDEB skin graft were positive and negative for human C7 (top row), respectively. All human skin grafts were positive for mouse C7 (middle row). Staining pattern in RDEB graft skin is fuzzy below the BMZ. The fuzziness of the BMZ especially in RDEB grafts was visualized by staining for pan‐species type IV collagen (C4) (bottom row). Nuclei are stained by DAPI. Bar represents 50 μm

To investigate the source of the observed murine C7 in these skin grafts, FISH using human X‐chromosome and Y‐chromosome probes was performed (Figure S2). First, to confirm the specificity of the probes, female and male healthy control skin sections were stained, in which more than 95% of dermal cells marked positive. In contrast, mouse skin samples were completely negative, confirming the specificity of the probes. Subsequently, skin sections of reconstituted skin grafts were analysed. Less than 15% of the dermal cells of human female control grafts were positive for the human X‐chromosome, whereas positive epidermal cell numbers were comparable to control skin, indicating that murine dermal cells might have invaded the dermal tissue of the human skin graft. Haematoxylin and eosin staining substantiated this hypothesis (Figure S3). The reticular dermis underneath the human graft resembled that of the surrounding murine skin and could be the result of wound healing by contraction of the murine skin. This suggests that at least a substantial portion of the reticular dermis underneath the graft is composed of murine tissue and that, from there, murine fibroblasts invade the papillary dermis directly underneath the graft and are the source of the observed murine C7 in the graft.

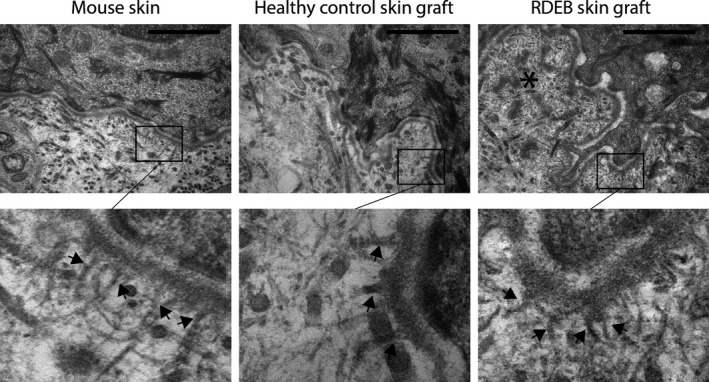

Subsequently, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed to determine the presence of AFs (Figure 2). In control grafts, TEM revealed a well‐defined papillary dermis and lamina densa. AFs were detected that were connected to the lamina densa, stretching into the papillary dermis. In RDEB grafts, widening of the lamina lucida and lamina densa offshoots were observed reflecting patient skin. Connected to the lamina densa, however, AFs were detected, which should be of murine origin, as the grafts were completely negative for human C7 as seen by IF.

Figure 2.

Ultramicrographs of the formation of AFs in in vivo reconstituted RDEB grafts. The lamina lucida and lamina densa were well defined and regular in mouse skin and healthy human control skin after grafting. RDEB graft skin revealed a lamina densa with downward offshoots (asterisk) and a lamina lucida of variable width. Interestingly, a five times higher magnification (lower panel) revealed the presence of anchoring fibrils (black arrows) projecting into the lamina densa in all samples, including the RDEB graft generated with C7‐negative keratinocytes. Bar represents 1 μm

5. CONCLUSIONS

Our results show that (a) murine C7 is deposited in human skin grafts, (b) this murine C7 is capable of forming AFs that attach to the lamina densa of the human skin graft, and (c) the C7 is most likely originating from murine fibroblasts, as our FISH data showed that mouse keratinocytes do not seem to invade the epidermis of the skin graft and previous studies have shown that normal human allogenic fibroblasts can also produce detectable C7 and AFs at the BMZ in RDEB skin.[9,11]

These results demonstrate that it is essential to distinguish human from murine C7 when C7 expression is used as outcome measurement, especially in preclinical studies using grafting models, as murine C7 can confound the interpretation of results. To do so, it is important to keep in mind that human and mouse C7 are highly homologous,[12] and most polyclonal antibodies (eg the widely used Calbiochem polyclonal rabbit‐anti‐human antibody) show cross‐reactivity (Figure S4). Therefore, in case the origin of C7 is essential for the interpretation of results, we advocate the use of validated species‐specific antibodies for IF and, whenever possible, to perform immunoelectron microscopy, as described by Keene and colleagues, to determine the exact origin of AFs.[13] Moreover, in functional studies into skin fragility of the RDEB graft area, if feasible, murine C7 should be taken into account due to possible reinforcement of the graft by murine C7 and formation of AFs.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

JB prepared the manuscript, experimental design and performed IF, imaging and grafting experiments. DK performed EM. DE performed IF and FISH. AG performed grafting experiments. GD provided histological examination. MJ, PvdA and AP provided supervision on study design and manuscript revisions.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Confirmation of species‐specificity of the human LH7.2 and murine AP23437PU monoclonal antibodies. Healthy control mouse (left column) and human (right column) skin cryosections were stained with the LH7.2 (upper row) and AP23437PU (lower row) antibodies. Species specificity for human (LH7.2) and mouse (AP23437PU) was confirmed and no cross‐reaction was observed

Figure S2 FISH staining suggests the presence of mouse fibroblasts in human skin grafts. FISH was performed on all samples with both human X‐chromosome (green dot) and Y‐chromosome (orange‐red dot) probes. FISH performed on mouse control, human female control, and human male control skin cryosections, revealed 0%, more than 95%, and more than 95% positive dermal cells, respectively (upper row). Both dermal and epidermal cells of mouse skin were completely negative for both probes. A healthy female control skin graft section (bottom row), showed less than 15% positively labelled dermal cells, a representative image for all skin grafts stained. The white line in the lower right panel indicates the border between the human skin graft epidermis and the mouse epidermis. Percentages represent positive dermal cells in the image. Nonspecific binding appeared as bright orange to yellow in all samples

Figure S3 Haematoxylin and Eosin staining of a healthy control skin graft. H/E staining shows a difference in density between the dermal tissue directly underneath and deeper underneath the skin graft. Mouse dermal tissue appears to have grown underneath the skin graft from the sides inwards. The image is a fusion of three images

Figure S4 Analysis of the species‐specificity of the Calbiochem and LH7.2 antibodies. Cryosections from a control graft generated using the in vivo method were stained with the LH7.2 monoclonal or Calbiochem polyclonal anti‐type VII collagen antibodies. The border between human graft and murine epidermis was identified in all sections (marked by white line) and imaged at comparable exposure times (~2 seconds) using a Leica IF microscope. Calbiochem (left) and LH7.2 (right) staining reveals that the Calbiochem detects both murine and human C7 (green). In contrast, the LH7.2 antibody specifically detects human C7 (green). Nuclei are visualized using DAPI (blue)

Appendix S1 Supplementary Methods

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the patients for their cooperation in this research. This research was funded by E‐RARE grant SpliceEB and Clinical Fellowship grant (90715614) from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW) to PCvdA.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Confirmation of species‐specificity of the human LH7.2 and murine AP23437PU monoclonal antibodies. Healthy control mouse (left column) and human (right column) skin cryosections were stained with the LH7.2 (upper row) and AP23437PU (lower row) antibodies. Species specificity for human (LH7.2) and mouse (AP23437PU) was confirmed and no cross‐reaction was observed

Figure S2 FISH staining suggests the presence of mouse fibroblasts in human skin grafts. FISH was performed on all samples with both human X‐chromosome (green dot) and Y‐chromosome (orange‐red dot) probes. FISH performed on mouse control, human female control, and human male control skin cryosections, revealed 0%, more than 95%, and more than 95% positive dermal cells, respectively (upper row). Both dermal and epidermal cells of mouse skin were completely negative for both probes. A healthy female control skin graft section (bottom row), showed less than 15% positively labelled dermal cells, a representative image for all skin grafts stained. The white line in the lower right panel indicates the border between the human skin graft epidermis and the mouse epidermis. Percentages represent positive dermal cells in the image. Nonspecific binding appeared as bright orange to yellow in all samples

Figure S3 Haematoxylin and Eosin staining of a healthy control skin graft. H/E staining shows a difference in density between the dermal tissue directly underneath and deeper underneath the skin graft. Mouse dermal tissue appears to have grown underneath the skin graft from the sides inwards. The image is a fusion of three images

Figure S4 Analysis of the species‐specificity of the Calbiochem and LH7.2 antibodies. Cryosections from a control graft generated using the in vivo method were stained with the LH7.2 monoclonal or Calbiochem polyclonal anti‐type VII collagen antibodies. The border between human graft and murine epidermis was identified in all sections (marked by white line) and imaged at comparable exposure times (~2 seconds) using a Leica IF microscope. Calbiochem (left) and LH7.2 (right) staining reveals that the Calbiochem detects both murine and human C7 (green). In contrast, the LH7.2 antibody specifically detects human C7 (green). Nuclei are visualized using DAPI (blue)

Appendix S1 Supplementary Methods