Abstract

During the last decade, Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Infantis (S. Infantis) has become more prevalent across Europe with an increased capability to persist in broiler farms. In this study, we aimed to identify potential genetic causes for the increased emergence and longer persistence of S. Infantis in German poultry farms by high-throughput-sequencing. Broiler derived S. Infantis strains from two decades, the 1990s (n = 12) and the 2010s (n = 18), were examined phenotypically and genotypically to detect potential differences responsible for increased prevalence and persistence. S. Infantis organisms were characterized by serotyping and determining antimicrobial susceptibility using the microdilution method. Genotypic characteristics were analyzed by whole genome sequencing (WGS) to detect antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes as well as plasmids. To detect possible clonal relatedness within S. Infantis organisms, 17 accessible genomes from previous studies about emergent S. Infantis were downloaded and analyzed using complete genome sequence of SI119944 from Israel as reference. In contrast to the broiler derived antibiotic-sensitive S. Infantis strains from the 1990s, the majority of strains from the 2010s (15 out of 18) revealed a multidrug-resistance (MDR) phenotype that encodes for at least three antimicrobials families: aminoglycosides [ant(3“)-Ia], sulfonamides (sul1), and tetracyclines [tet(A)]. Moreover, these MDR strains carry a virulence gene pattern missing in strains from the 1990s. It includes genes encoding for fimbriae clusters, the yersiniabactin siderophore, mercury and disinfectants resistance and toxin/antitoxin complexes. In depth genomic analysis confirmed that the 15 MDR strains from the 2010s carry a pESI-like megaplasmid with resistance and virulence gene patterns detected in the emerged S. Infantis strain SI119944 from Israel and clones inside and outside Europe. Genotyping analysis revealed two sequence types (STs) among the resistant strains from the 2010s, ST2283 (n = 13) and ST32 (n = 2). The sensitive strains from the 1990s, belong to sequence type ST32 (n = 10) and ST1032 (n = 2). Therefore, this study confirms the emergence of a MDR S. Infantis pESI-like clone of ST2283 in German broiler farms with presumably high tendency of dissemination. Further studies on the epidemiology and control of S. Infantis in broilers are needed to prevent the transfer from poultry into the human food chain.

Keywords: Salmonella Infantis, broiler, emergence, multidrug resistance, pESI-like plasmid, whole genome sequencing

Introduction

Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Infantis (S. Infantis) belongs to the group of Salmonella serovars, which plays a major epidemiological role in humans and animals. In the European Union (EU), S. Infantis has been the third most common serovar in humans since 2006 with a relative share between 1% and 2% (EFSA, 2019). Although this serovar is prevalent also in pigs and cattle (Rajic et al., 2005; Lindqvist and Pelkonen, 2007), poultry especially broiler and their products have been identified as one of the most important sources of human infection with S. Infantis (EFSA, 2019, 2020). In 2018, S. Infantis was the most frequently reported serovar in fowl in the EU (EFSA, 2019), accounting for 36.7% of all Salmonella isolates. Moreover, unlike previous years, S. Infantis was not only detected in a few numbers of countries but widespread among most member states and massively reported from broilers (36.5% of all serotyped isolates) and broiler meat (56.7%).

During the last years, antimicrobial resistance has emerged in S. Infantis organisms from different animal sources and humans in various European countries (Nógrády et al., 2012; EFSA, 2020). Increasing incidence and dissemination of different multidrug-resistant (MDR) S. Infantis clones in broiler populations resulted in spreading of the organisms in the food chain and via poultry products to humans in countries such as Hungary (Olasz et al., 2015), Italy (Franco et al., 2015), Switzerland (Hindermann et al., 2017), Slovenia (Pate et al., 2019), and Russia (Bogomazova et al., 2019). Furthermore, observations are indicating a long persistence of S. Infantis in broiler farms and increased resistance against cleaning and disinfection procedures (Asai et al., 2007; Nógrády et al., 2007, 2008; Ross and Heuzenroeder, 2008; Pate et al., 2019). Thus, we were interested whether recent S. Infantis organisms gained new properties resulting in the modified characteristics.

There is evidence that the acquisition of a conjugative mega-plasmid provides the bacteria with new resistance properties (EFSA, 2020) but might also confer virulence-associated characteristics, higher resistance against heavy metals or disinfectants and fitness characteristics (Aviv et al., 2014).

In view of the increased prevalence of S. Infantis also in German broiler production in recent years (EFSA, 2020), the question raised on possible reasons. Therefore, this study aimed to characterize and compare S. Infantis strains originated from different broiler farms in Germany from 20-years distant decades, the 1990s and the 2010s. S. Infantis organisms isolated in different decades were phenotypically characterized by serotyping and determining the antimicrobial susceptibility. In this study, whole genome sequencing (WGS) and bioinformatics analysis were used to describe the genetic traits of S. Infantis strains from different German broiler farms collected from 20-years distant decades.

Materials and Methods

Strain Selection

In this study, we analyzed a dataset consisting of 30 S. Infantis strains that cover a wide range of broiler farms in Germany (Table 1). Eighteen isolates were collected during the 2010s (time frame: 2014–2020) and 12 strains were isolated two decades earlier, in the 1990s (time frame: 1992–1998). S. Infantis strains were provided by the National Reference Laboratory for Salmonella at the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) or were received after request from regional diagnostic laboratories in different federal states in Germany. To compare the sequenced German S. Infantis strains with previously reported emergent S. Infantis clones, we searched for recent publications regarding S. Infantis. The criteria of selection of strains were source (broiler), region (central Europe) and, period of time when they were collected (between the 1990s and the 2010s). Thus, we downloaded sequence data of S. Infantis (n = 17) from Hungary (Olasz et al., 2015; Wilk et al., 2016, 2017) and Italy (Franco et al., 2015) (Supplementary Table S1). Beyond this criteria, we included strains from Israel where pESI was first studied (Aviv et al., 2014) and kept the strains 1326/28 (LN649235) from the United Kingdom and the non-broiler strain 335-3 (ATHK00000000) as representatives of the historical, or so-called “pre-emergent” strains. For comparison purposes, we included the recently published complete genome sequence of the S. Infantis strain 119944 harboring the pESI like megaplasmid from Israel (Cohen et al., 2020).

TABLE 1.

Epidemiological data and phenotypic AMR profile of S. Infantis strains used in this study.

| Strain | Sample | Region of isolation | Year of isolation | Phenotypic AMR profile |

| 19PM0346 | 2945 | Bavaria farm 1 | 1992 | SMX |

| 19PM0348 | 2947 | Bavaria farm 2 | 1992 | SMX |

| 19PM0349 | 2948 | Bavaria farm 3 | 1992 | SMX |

| 19PM0350 | 2949 | Lower Saxony farm 1 | 1992 | SMX |

| 19PM0351 | 2951 | Lower Saxony farm 2 | 1994 | SMX |

| 20PM0240 | 3222 | Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania | 1994 | SMX |

| 20PM0243 | 3225 | State of Hesse farm 2 | 1995 | SMX |

| 20PM0245 | 3227 | Thuringia | 1995 | SMX |

| 20PM0248 | 3230 | State of Hesse farm 3 | 1996 | SMX |

| 20PM0252 | 3234 | Baden-Wuerttemberg farm 2 | 1997 | SMX |

| 20PM0257 | 3239 | Rhineland-Palatinate farm 2 | 1998 | SMX |

| 20PM0260 | 3242 | Lower Saxony farm 4 | 1998 | SMX |

| 20PM0261 | 3243 | Bavaria farm 4 | 2014 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

| 20PM0263 | 3245 | Lower Saxony farm 5 | 2014 | SMX |

| 20PM0267 | 3249 | Saxony-Anhalt farm 1 | 2015 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

| 20PM0268 | 3250 | Bavaria farm 5 | 2015 | SMX |

| 20PM0270 | 3252 | Saxony-Anhalt farm 2 | 2015 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

| 20PM0271 | 3253 | Brandenburg farm 1 | 2016 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

| 20PM0273 | 3255 | Lower Saxony farm 6 | 2016 | SMX |

| 20PM0275 | 3257 | Bavaria farm 6 | 2016 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

| 19PM0355 | 2954 | Baden-Wuerttemberg farm 1 | 2017 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

| 19PM0358 | 2957 | Brandenburg farm 1 | 2018 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

| 19PM0360 | 2959 | Bavaria farm 4 | 2019 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

| 19PM0148 | 2747 | Bavaria farm 5 | 2019 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

| 19PM0149 | 2748 | Bavaria farm 6 | 2019 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

| 19PM0150 | 2749 | Bavaria farm 7 | 2019 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

| 19PM0151 | 2750 | Baden-Wuerttemberg farm 2 | 2019 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

| 19PM0153 | 2752 | Baden-Wuerttemberg farm 3 | 2019 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

| 19PM0154 | 2753 | Bavaria farm 8 | 2019 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

| 20PM0045 | 3027 | Bavaria farm 6 | 2020 | SMX-CIP-TET-NAL-TGC |

SMX, sulfamethoxazole; CIP, ciprofloxacin; TET, tetracycline; NAL, nalidixic acid; TGC, tigecycline.

Serotyping and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

All Salmonella isolates were serotyped using poly- and monovalent anti-O as well as anti-H sera (SIFIN, Germany) according to the Kauffmann–White scheme (Grimont and Weill, 2007). Antimicrobial susceptibility of the S. Infantis strains was assessed by determining the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) using the broth microdilution method with SensititreTM EUVSEC plates (Trek Diagnostic Systems Ltd., East Grinstead, United Kingdom). Epidemiological cut-off values were used according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST, 2018). Antimicrobial susceptibilities to sulfamethoxazole (SMX), trimethoprim (TMP), ciprofloxacin (CIP), tetracycline (TET), meropenem (MERO), azithromycin (AZI), nalidixic acid (NAL), cefotaxime (FOT), chloramphenicol (CHL), tigecycline (TGC), ceftazidime (TAZ), colistin (COL), ampicillin (AMP), and gentamicin (GEN) were examined.

Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

For paired-end sequencing with Illumina, Genomic DNA of 30 S. Infantis strains was extracted and purified using the QIAGEN® Genomic-tip 20/G kit (QIAGEN, Germany) and the Genomic DNA Buffer Set (QIAGEN, Germany). The concentration of the DNA was determined using the Qubit dsDNA BR assay kit (Invitrogen, United States). Sequencing libraries were created using the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina Inc., United States). Paired-end sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq instrument according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina Inc., United States).

For long-read sequencing with MinION, a sequencing library was prepared using the Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) 1D Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK109) with the Native Barcoding Expansion Kit (EXP-NBD104) as recommended by the manufacturer. Raw FAST5 files were processed using Guppy toolkit (v. 3.4.1) (Oxford Nanopore Technologies). The Guppy command guppy_basecaller was used for basecalling and guppy_barcoder was used for demultiplexing. De novo assembly for long sequencing reads was performed using Flye (v. 2.6) (Kolmogorov et al., 2019). Assembly polishing was performed with four rounds by Racon (v. 1.4.3) (Vaser et al., 2017) and one final round with Medaka (v. 0.10.0). Finally, Pilon (v. 1.23) (Walker et al., 2014) was used to correct the final assembled data from Nanopore with Illumina reads using standard settings.

To analyze the sequencing data in a standardized manner, the Linux-based bioinformatics pipeline WGSBAC was used (v. 2.0.0)1 (FLI_Bioinfo, 2020). Input for the pipeline was raw Illumina data and already assembled data (MinION). WGSBAC starts with quality control using FastQC (v. 0.11.7)2 (Andrews, 2018). Next, it calculates the raw coverage by the number of reads multiplied with their average read length and divided by the genome size. WGSBAC performs assembly using Shovill (v. 1.0.4) (Seemann, 2018) an optimizer for SPAdes assembler (Bankevich et al., 2012).

The quality of the assembled genomes is then checked using QUAST (v. 5.0.2) (Gurevich et al., 2013). Genome annotation is made by Prokka (v. 1.14.5). In order to identify contamination, the pipeline uses Kraken 2 (v. 1.1) (Wood et al., 2019) and the database Kraken2DB to classify both reads and assemblies. For in silico serotyping, WGSBAC utilizes SISTR (v. 1.0.2) (Yoshida et al., 2016) on the assembled genomes.

For genotyping, WGSBAC uses classical multilocus sequence typing (MLST) on assembled genomes using mlst software (v. 2.16.1)3 (Seemann, 2014a) that incorporates the PubMLST database4 (Jolley et al., 2018). Furthermore, the pipeline includes mapping based SNP-typing using Snippy (v. 4.3.6)5 (Seemann, 2014b) with standard settings and FastTree (v. 2.1.10) (Price et al., 2009) to calculate phylogenetic trees from SNPs. To infer phylogeny based on core genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST), we used the external software Ridom Seqsphere+ (v. 5.1.0) (Junemann et al., 2013) with default settings and the specific core genome scheme (cgMLST v2) for Salmonella enterica with 3,002 target loci developed by Enterobase (Alikhan et al., 2018).

For detection of antimicrobial resistance genes (AMR), virulence factors and plasmid replicon genes, WGSBAC uses Abricate (v. 0.8.10)6 (Seemann, 2015) and the databases: ResFinder (Zankari et al., 2012) and NCBI (Feldgarden et al., 2019a), Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) (Chen et al., 2005) and PlasmidFinder (Carattoli et al., 2014), respectively. For the detection of point mutations in the gene gyrA leading to AMR, we used the software AMRFinderPlus (v. 3.6.10) (Feldgarden et al., 2019b).

For a deeper molecular characterization of the strains, we downloaded specific pESI119944-encoded gene sequences and created customized databases for Abricate (Supplementary Table S2). These databases include sequences of genes encoding for Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPIs), Ipf and K88-like fimbrial clusters and pESI fitness determinants as the toxin-antitoxin (T/AT) system (CcdAB and PemK/MazF) and the mercury operon. Furthermore, for plasmid typing, allele sequences for incompatibility groups of plasmids IncI1 (five loci) and IncF RST (seven loci) were downloaded from the Plasmid PubMLST database7 (Carattoli and Hasman, 2020). In order to complete the plasmid genomic characterization and to test the chimeric nature of pESI-like plasmids as described before (Aviv et al., 2014), we tested the detection of the gene sequence encoded for RepFIB replication protein A (repB) and the oriV of IncP1 plasmids. We used the external software Geneious Prime (v. 2019.2.3)8 to complete the plasmid strain annotation and for visualization of its main genomic features.

Two phylogenetic trees were constructed for the pESI-like positive strains using Snippy to study the plasmid SNP-based phylogeny. One tree using the plasmid sequence (CP047882) as reference and a second one using the chromosome sequence (CP047881) as reference of the complete genome sequence of SI119944 strain (Cohen et al., 2020). Trees were compared using the tanglegram function of the tool Dendroscope (v 3.5.9) (Huson and Scornavacca, 2012).

Results

Serotyping and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

All isolates were typed according to the Kauffmann–White scheme and revealed the complete antigenic formula (6, 7: r: 1, 5) for S. Infantis. As listed in Table 1, all S. Infantis strains from the 1990s were only resistant against SMX. Among the isolates from the 2010s, three strains were resistant to SMX and 15 were multidrug-resistant to SMX, CIP, TET, NAL, and TGC.

Genomic Features of Genomes of S. Infantis Strains

WGS of the 30 S. Infantis strains revealed general genomic characteristics and allowed genoserotyping of the strains (Supplementary Table S3). We sequenced an average of 1,439,617 reads per sample (range: 524,688–2,509,738). On average, assembled genomes consisted of 54 contigs (range: 37–91) with an average read-coverage of 68 fold (range: 24–128). The average genome size was 4.8 Mbp (range: 4.6–4.9 Mbp), GC content was 52.2% and N50 values average 257,721 (range: 90,139–445,475). Kraken2 on Illumina reads classified an average of 95.31% of reads as “Salmonella” on the genus level and an average of 94.42% of reads as “Salmonella enterica” at the species level. To confirm the serological serotyping, SISTR was used for in silico molecular typing and predicted serovar Infantis for all the strains included in the study corroborating the phenotypic findings.

Genotyping and Phylogeny of S. Infantis Strains

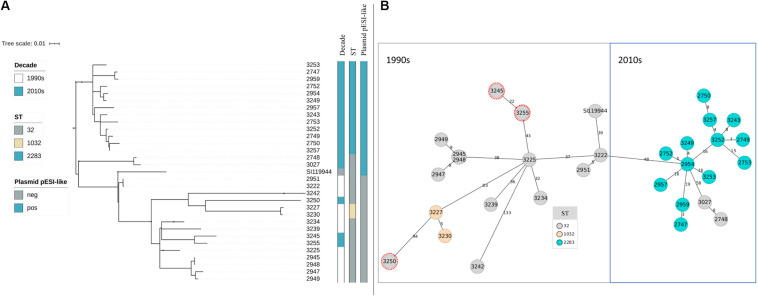

After assessing the general sequencing characteristics, classical MLST on the assembled genomes was carried out to get a broad overview of the S. Infantis genotypes (Table 2). Among the complete dataset, 15 out of 30 isolates examined belong to ST32. The remaining 15 belong to two single-locus variants of ST32, namely ST2283 (in the gene sucA) and ST1032 (in the gene dnaN). The majority of the strains from the 1990s belong to ST32 (n = 10) while two strains belong to ST1032. The majority of the strains from the 2010s belong to ST2283 (n = 13) while five strains belong to ST32. Within the dataset from the 2010s, only two strains that belong to ST32 revealed the same MDR pattern as S. Infantis strains with ST2283. For a deeper phylogenetic analysis of the 30 S. Infantis strains, a minimum spanning tree based on core genome MLST (cgMLST) and a phylogenetic tree based on single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were constructed. Although both approaches differ strongly, they produced similar results (Figures 1A,B). Both phylogenetic approaches group the strains into two distinct decade- and ST-related groups except for samples 2748 and 3027 that belong to ST32 but they are grouped with the samples collected in the 2010s (Figure 1B) and three strains from the 2010s that are included within the group of the 1990s as they have ST32 (marked in red in Figure 1B). On average, the distance between the strains was 145 SNPs and 76 alleles.

TABLE 2.

Sequence type (ST), resistance genes (ESIr pattern and other) and plasmid replicons detected in broiler-derived S. Infantis strains from Germany and comparison with the complete genome sequence of plasmid pESI detected in S. Infantis SI119944 strain from Israel.

| Sample | Year of isolation | MLST (ST) | Resistance genes pattern (ESIr) | Other resistance genes | Plasmid replicon |

| 2945 | 1992 | 32 | − | aac(6′)-Iaa | – |

| 2947 | 1992 | 32 | − | aac(3)VIa, ant(3“)-Ia, sul1, aac(6′)-Iaa | IncI1-I(Gamma) |

| 2948 | 1992 | 32 | − | aac(6′)-Iaa | – |

| 2949 | 1992 | 32 | − | aac(3)VIa, ant(3“)-Ia, sul1, aac(6′)-Iaa | IncI1-I(Gamma), IncFIC(FII), IncFII(pSFO) |

| 2951 | 1994 | 32 | − | aac(6′)-Iaa | – |

| 3222 | 1994 | 32 | − | aac(6′)-Iaa | – |

| 3225 | 1995 | 32 | − | aac(6′)-Iaa | – |

| 3227 | 1995 | 1032 | − | aac(6′)-Iaa | – |

| 3230 | 1996 | 1032 | − | aac(6′)-Iaa | – |

| 3234 | 1997 | 32 | − | aac(6′)-Iaa | – |

| 3239 | 1998 | 32 | − | aac(6′)-Iaa | – |

| 3242 | 1998 | 32 | − | aac(6′)-Iaa | – |

| 3243 | 2014 | 2283 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| 3245 | 2014 | 32 | − | aac(6′)-Iaa | – |

| 3249 | 2015 | 2283 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| 3250 | 2015 | 32 | − | aac(6′)-Iaa | – |

| 3252 | 2015 | 2283 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| 3253 | 2016 | 2283 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| 3255 | 2016 | 32 | − | aac(6′)-Iaa | – |

| 3257 | 2016 | 2283 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| 2954 | 2017 | 2283 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| 2957 | 2018 | 2283 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| 2959 | 2019 | 2283 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| 2747 | 2019 | 2283 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| 2748 | 2019 | 32 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| 2749 | 2019 | 2283 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| 2750 | 2019 | 2283 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| 2752 | 2019 | 2283 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| 2753 | 2019 | 2283 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| 3027 | 2020 | 32 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, gyrA-S83Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

| SI119944 | 2008 | 32 | + | aac(6′)-Iaa, dfrA14, gyrA-D87Y | IncFIB(pN55391) |

FIGURE 1.

(A,B) Phylogeny of broiler-derived S. Infantis strains in Germany and S. Infantis SI119944 from Israel. (A) Phylogenetic tree based on SNPs representing two main decade- and ST-related groups as the minimum spanning tree based on cgMLST. (B) Plasmid pESI-like is presented in the majority of samples from the 2010s (n = 15) and absent for the data from the 1990s. Samples 3227 and 3230 that belong to ST1032 are grouped within the 1990s group as they do not present the plasmid pESI-like. Note that samples 2748 and 3027 belong to ST32 but they are grouped with the samples collected in the 2010s (B) and that three strains from the 2010s are included within the group of the 1990s as they have ST32 (marked in red in B).

Resistance and Virulence Genes Patterns

The analysis of the genome sequences revealed an AMR gene pattern specific for the 15 MDR strains from the 2010s. We named this pattern ESIr (Emergent S. Infantis resistance pattern) and it consists of the AMR genes: ant(3“)-Ia (aminoglycoside resistance), sul1 (sulfonamide resistance), tet(A) (TET resistance) and qacEdelta1 [quaternary ammonium compound (QAC) and disinfectant resistance] (Table 2). Additionally, we detected a point mutation in the gene gyrA (gyrA-S83Y) leading to resistance against (fluoro)quinolones (Supplementary Table S4). The remaining three strains from the 2010s dataset did not reveal any of these resistance genes. Two strains from the 1990s, (2947 and 2949) carry the genes ant(3“)-Ia, sul1 and qacEdelta1 as well as the gene aac(3)-VIa (aminoglycoside resistance) but not the gene tet(A). The chromosomally encoded gene aac(6’)-Iaa was detected among all the samples included in this study.

We detected a specific gene pattern of virulence genes among the 15 MDR strains from the 2010s (Table 3). We named this pattern ESIv (Emergent S. Infantis virulence) which consists of genes associated with the fimbrial clusters: K88-like fimbria (Klf) and the S. Infantis plasmid-encoded fimbria (Ipf) (Aviv et al., 2017). Moreover, the pattern includes genes encoding for the virulent yersiniabactin operon (fyuA, irp1, irp2, ybtA, ybtE, ybtP, ybtQ, ybtS, ybtT, ybtU, ybtX) and the mercury (mer) operon (merR, merT, merP, merC, merA, merD, merE) conferring mercury resistance. Finally, ESIv pattern consists of the gene complex ccdA/B and the pemK/I family (T/AT system). Isolates from the 1990s did not show any of these genes. Apart from the ESIv pattern, we found among all the samples from the study the presence of ten SPIs: SPIs-1-6, SPI-9, SPIs-11-12, and CS-54 (Supplementary Table S5).

TABLE 3.

Virulence and fitness genes detected in broiler-derived S. Infantis strains from Germany (ESIv pattern) and comparison with the complete genome sequence of plasmid pESI detected in S. Infantis SI119944 strain from Israel.

| Sample | Year of isolation | K88-like fimbria (Klf) | Infantis plasmid encoded fimbria (Ipf) | mer operon | Yersiniabactin system | Toxin/antitoxin system (T/AT) |

| 2945 | 1992 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2947 | 1992 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2948 | 1992 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2949 | 1992 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2951 | 1994 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3222 | 1994 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3225 | 1995 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3227 | 1995 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3230 | 1996 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3234 | 1997 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3239 | 1998 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3242 | 1998 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3243 | 2014 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3245 | 2014 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3249 | 2015 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3250 | 2015 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3252 | 2015 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3253 | 2016 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3255 | 2016 | − | − | + | − | − |

| 3257 | 2016 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2954 | 2017 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2957 | 2018 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2959 | 2019 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2747 | 2019 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2748 | 2019 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2749 | 2019 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2750 | 2019 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2752 | 2019 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2753 | 2019 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3027 | 2020 | + | + | + | + | + |

| SI119944 | 2008 | + | + | + | + | + |

As previously reported (Bogomazova et al., 2019), similar resistance and virulence gene patterns have been determined by the presence of a pESI-like plasmid carried by emergent S. Infantis strains. Likely, in the case of the strains of this study, the presence of a pESI-like plasmid could explain this genetic profile. Therefore, we aimed at the genomic detection and further characterization of this pESI-like plasmid among our strains.

Detection, Genomic Characterization and Phylogeny of a pESI-Like Plasmid

First, we scanned for replicon sequences of plasmids (Supplementary Table S6). All the 15 MDR strains positive to ESIr and ESIv patterns, presented the replicon IncFIB (pN55391) (Table 2). A genomic in-depth analysis for the typification of the plasmids revealed that the 15 strains positive for the IncFIB(pN55391) replicon, had the profile: ardA2, pilL3, sogS9, trbA21 while repI1 was absent. However, they were positive for the RepFIB replication protein A (repB). Besides, they were positive for the detection of the sequence of the plasmid RK2 (from E. coli) DNA transposon (Tn1723) insertion sites (M20134) revealing the chimeric nature of the pESI-like plasmid as described previously (Aviv et al., 2014, 2016).

The samples 2947 and 2949 from the 1990s were positive for replicon IncI1-I(Gamma) and had the complete IncI gene profile: ardA4, pilL1, sogS2, trbA13, repI1. Sample 2949 simultaneously carries IncFIC(FII) and IncFII(pSFO) replicons and two alleles of IncF RST: FII91 and FIC3 (Supplementary Table S6). Interestingly, sample 3255 from the 2010s, was negative for the presence of IncFIB (pN55391); however, it carried additionally three different replicons: IncFIC(FII), IncFII(S) and IncFII(SARC14) for IncF plasmids (Supplementary Table S6). Sample 3255 did not present any gene from the IncI1 scheme, nor repB, but two genes from the IncF RST scheme: FIIS5 and FIC3. The remaining non-resistants trains from the dataset did not contain any gene for an incompatibility group of plasmids.

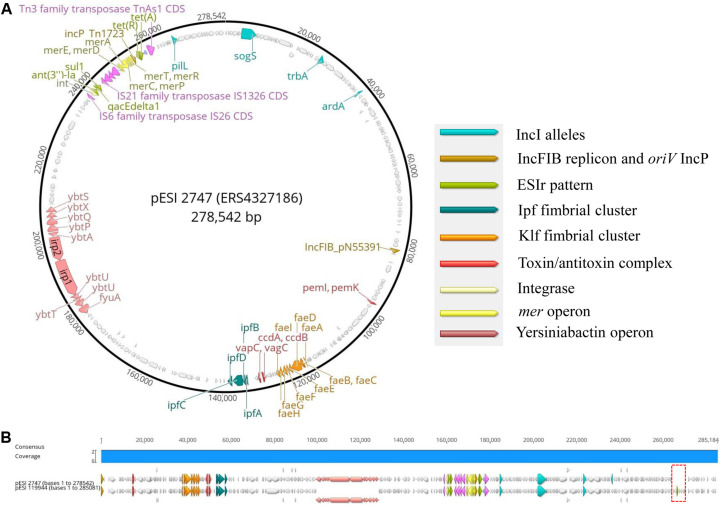

Second, to add further evidence that the 2010s prevalence of S. Infantis in German broilers may be due to the presence of a pESI-like megaplasmid, we downloaded and examined the complete genome sequence of the megaplasmid pESI119944 found for the first time in the strain SI119944 in Israel (Aviv et al., 2014). Indeed, the analysis of the complete sequence of this plasmid showed the presence of the replicon IncFIB(pN553391), the allele profile of an IncI, the origin of replication of an IncP and repB (Supplementary Table S6). As shown in Tables 2, 3, main resistance and virulence traits detected among the German strains positive for replicon IncFIB(pN553391), were also present in the Israelian strain SI119944. Third, to have an in-depth comparison of the pESI-plasmid found within the German strains, we performed Oxford Nanopore sequencing of the sample 2747 that represent the samples from the 2010s and meets the characteristics described above regarding resistance, virulence genes, and plasmid nature. The hybrid assembly of sample 2747 resulted in two closed contigs corresponding to the chromosome (4,678,881 bp length) and the pESI-like plasmid (278,542 bp length) that we designated as pESI2747. The N50 value of the genome was 4,678,881 bp and the GC content was 52.18%. Kraken2 gave a match of 100% for Salmonella enterica. Figures 2A,B show the main features of the alignment of pESI119944 from Israel and pESI2747 from Germany. The alignment shows a consensus sequence of ∼285,184 bp. This consensus sequence consists of a common fragment of ∼277,693 bp (∼97.37%) between both sequences and a non-common region of ∼7,301 bp (∼2.56%). The repB gene coding for RepFIB replication protein A is located in the positions 80,555 and 81,580 bps in pESI2747, while on pESI119944 it is located at the beginning of the plasmid. Moreover, the genes ardA, pilL, sogS, trbA were found as well in different locations along pESI2747 compared to pESI119944. The sequence of an origin of replication for IncP plasmid was found as well in both plasmid sequences between the mer operon and the resistance genes tet(A) and tet(R) as previously described (Aviv et al., 2014, 2016). In pESI2747, we found the ESIr and the ESIv pattern common for the 15 MDR strains from the 2010s. Resistance genes ant(3“)-la, sul1 and qacEdelta1 were located together in a region flanked by an IS6 transposase IS26, Integrase/recombinase (int) (Uniprot: P62592)9 and IS21 family transposase IS1326. Resistance genes to TET tet(A) and tet(R) were found as well together, having upstream the Tn3 family transposase TnAs1. In the non-common part, we found the TMP resistance encoding gene dfrA14 only presented in the sequence of pESI119944. Regarding virulence, we found the k88-like fimbria (Klf) cluster on the sequences of both plasmids spanning a region of ∼8,000 bp and the Ipf cluster that occupies a region of 5,100 bp. Between them, we found the gene cluster ccdA-ccdB encoding for the toxin/antitoxin system and the vagC and vapC genes. The pemK-pemI is located in position 95,086. Moreover, we found the 11 genes of the yersiniabactin operon spanning a region of ∼29,000 bp.

FIGURE 2.

(A,B) Main genomic traits and alignment of the complete plasmid sequence of pESI119944 from the Israelian strain SI119944 and pESI2747 from the German strain 19PM0148. The red frame indicates the non-common fragment in the alignment.

To study, if all German strains potentially carrying pESI have a similar plasmid structure as pESI2747, we mapped the Illumina short reads to the sequence of pESI119944 and analyzed their coverage vector (Supplementary Figure S1). We found that the positive strains cover practically the complete sequence of pESI119944 except for a gap at the end of the reference sequence suppose to be the non-common part observed between our pESI-like plasmid and the pESI119944. In summary, we add evidence that multidrug-resistant strains in the 2010s carry a pESI-like megaplasmid.

Finally, we were interested if the plasmid evolves independently or if there has occurred a co-evolution together with the chromosomes. Therefore, we studied the plasmid-based SNP phylogeny as previously performed (Alba et al., 2020) for the 15 S. Infantis strains harboring the pESI-like plasmid (Supplementary Figure S2). In general the plasmid phylogeny seems to be similar to the chromosomal phylogeny.

Genomic Characteristics of S. Infantis Strains From Israel, Hungary, and Italy

To compare our findings with recently published results from the emergent S. Infantis clones, we downloaded a total of 17 genomes from studies performed in Italy (Franco et al., 2015), Hungary (Olasz et al., 2015; Wilk et al., 2016, 2017) and Israel (Aviv et al., 2014) as described above and analyzed them using our pipeline (Supplementary Table S1). Genotyping revealed that ST32 was the only sequence type of S. Infantis strains presented within the data from Israel, Hungary and Italy while ST2283 was not detected. PlasmidFinder found the replicon IncFIB(pN55391) in 13 out of 17 of the strains and the majority of them (n = 12) presented the IncI profile: ardA2, pilL3, sogS9, trbA21, and repI1 absent (Supplementary Table S6). Additionally, we detected two replicons (IncX1 and IncX3) in two Hungarian strains (SI240/16 and SI3337/12) and IncI1-I(Gamma) in one Italian strain (ERS846145) with IncI profile including the repI1. As expected, samples from Hungary SI69/04, Israel 335-3 and United Kingdom 1326/28 collected before the 2000s did contain neither plasmid replicons, nor IncI genes. Abricate using ResFinder, revealed a variety of 15 different resistance genes among the S. Infantis harboring the pESI-like plasmid (Supplementary Table S4). The ESIr [ant(3“)-la, sul1, tet(A) and qacEdelta1] was found among 10 out of 17 strains from the three countries. The remaining strains had a variation of this pattern and presented other additional genes. Especially, the Italian strains present a wide variety of resistance genes including resistance genes related to extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL), like blaCTX-M-1 as reported previously (Franco et al., 2015). Three out of seven Hungarian strains presented ESBL genes as well like the blaCTX-M-14 or blaTEM-104.

Chromosomal mutations of gene gyrA were found as well: gyrA-S83Y (8 out of 17) and gyrA-D87G (4 out of 17), gyrA_D87Y was found only in SI119944. The ESIv pattern described above within the German S. Infantis was found in 12 out of 16 strains (Supplementary Table S5). Therefore, the results from this study are in line with the findings in other European countries regarding the emergence of multidrug and virulent S. Infantis clones.

To see if there is a clonal transmission of the strains, a minimum spanning tree based on cgMLST was constructed (Supplementary Figure S3). German S. Infantis strains of ST2283 form 2010s are close to two Hungarian strains that were reported as new S. Infantis clones (Nógrády et al., 2012). The smallest difference between external strains and German pESI-like strains is 37 alleles between the Hungarian SI54/04 and the German 2954, therefore we could not detect any clonal relatedness. The two ST32 strains from the 2010s are most closely related to two emergent S. Infantis strains from Italy. We could detect clonal transmission between two Italian strains where the smallest number of different alleles was 1.

Discussion

Studies performed within and outside Europe revealed an emergent dissemination of S. Infantis clones in humans and several animal species (Nógrády et al., 2007, 2008, 2012; Aviv et al., 2014; Franco et al., 2015; Olasz et al., 2015; Yokoyama et al., 2015; Wilk et al., 2016; Hindermann et al., 2017; Szmolka et al., 2018; Acar et al., 2019; Bogomazova et al., 2019). There is evidence that the acquisition of a conjugative megaplasmid provides the bacteria with new resistance properties which might have contributed to the increased occurrence of this serovar. An in-depth analysis of the genetic characteristics of the plasmid called pESI (Aviv et al., 2014) or similar pESI-like plasmids (Franco et al., 2015; Szmolka et al., 2018) revealed that they also encode for virulence-associated characteristics, resistance to heavy metals or disinfectants and fitness characteristics. The analysis and genomic comparison of the complete genome sequence of SI119944 from Israel (Cohen et al., 2020) and strain 2747 from Germany demonstrate and confirm the characteristic resistance, virulent as well as fitness traits encoded on a pESI-like plasmid. Furthermore, results from this study confirm the observed switch in the occurrence of S. Infantis organisms in broilers from non-MDR strains screened until the 2000s (Asai et al., 2007; Shahada et al., 2008; Wilk et al., 2017) to the emergence of MDR clones collected during and after the end of the 2000s (Nógrády et al., 2007, 2008, 2012). ST32 is a highly conserved sequence type of S. Infantis (Monte et al., 2019) and was the dominating MLST type isolated from various and numerous sources (broilers, pigs, cattle, food, human) in different European countries (Hauser et al., 2012; Hindermann et al., 2017; Gymoese et al., 2019). In this study, we describe the occurrence of two single locus variants of ST32 within the S. Infantis from German broiler production: ST2283 and ST1032. The emergence of ST2283 in S. Infantis organisms from the 2010s is linked with the presence of a pESI-like plasmid that confers a MDR pattern that has not been found among S. Infantis ST32 strains originating from the 1990s. However, we also identified two ST32 strains of S. Infantis from the 2010s harboring the resistant coding plasmid. We observed general concordance in cluster separation between the chromosome-based tree and plasmid-based tree in all strains harboring pESI-like megaplasmid (ST32 and ST2283) as shown also by Alba et al. (2020). Therefore, we hypothesize that the plasmid has co-evolved with the chromosome and both STs gained the plasmid in two (or more) evolutionary independent events. However, a rather rare occurrence of MDR clone ST32 compared with the higher prevalence of MDR clone ST2283 in recent years indicates an obvious greater tendency of dissemination of this clone in Germany and perhaps European broiler production, and therefore, another until now not detected property of ST2283. We also detected two non-resistant ST1032 clones from the 1990s. This variant of ST32 had been described before in a non-resistant isolate from food (Alba et al., 2020). In this study, bioinformatics analysis revealed a correlation between the resistance gene pattern named as ESIr [ant(3“)-la, sul1, tet(A)] and the phenotypic resistance profile to aminoglycosides, sulfonamides, and TETs. Furthermore, gen aac(6’)-Iaa was not located on pESI119944 but on the chromosome. In line with the literature, we found the gene aac(6’)-Iaa to be chromosomal-encoded gene (Salipante and Hall, 2003). On the other hand, German broiler derived S. Infantis strains showed phenotypic resistance to quinolones like CIP and NAL. Genotype findings do correlate with the phenotypic results as we detected the well-studied mutation in gyrA gene that codifies for resistance to those antibiotics (Chen et al., 2019). The predominant MDR pattern found among the emergent S. Infantis clones from Europe consists mainly of antimicrobials that belong to the major classes of antibiotics FOT, CIP, cephalosporin, TET, sulfonamide, fluoroquinolone, and TMP (Cloeckaert et al., 2007; Franco et al., 2015; Acar et al., 2019). Phenotypic and genotypic variants of this pattern have been observed in Hungary related to two different pulsotype clusters (Nógrády et al., 2012). Variants of this MDR pattern including ESBL resistant isolates of S. Infantis were also found in Italy and Germany (Franco et al., 2015; Fischer et al., 2017). Resistance and virulence traits coevolved and interfere in the ecology of a strain (Beceiro et al., 2013). Thus, the increasing emergence of a strain is not only dependent on antimicrobial resistance, but also on virulence, bacteriocin secretion, biocide resistance and, biofilm formation (Acar et al., 2019). Consequently, in this study, the bioinformatics analysis for virulence determinants showed a common pattern in virulence and fitness genes within the MDR isolates. Salmonella pathogenicity islands and other different gene complexes that encode for fimbriae production, adherent and non-adherent products, as well as curli structures, are of special interest because of their involvement in host colonization, persistence, motility, and invasion (Barnhart and Chapman, 2006; Rychlik et al., 2009; Aviv et al., 2017). The strong dissemination of S. Infantis not only in broilers during the last two decades wonders whether the increased antimicrobial resistance, the swift in MLST type, the virulence properties, the capability of biofilm formation or other unknown factors are responsible for this emergence. Different hypotheses try to explain this phenomenon. For example, it is suspected that the increased prevalence of S. Infantis could be due to the general decreased prevalence of S. Enteritidis in poultry farms (Szmolka et al., 2018). It is also suggested that the EU trade of broiler chicken and the pyramidal structure of the poultry industry may be factors of the rapid spread of emergent clones of S. Infantis carrying the pESI-like plasmid beyond national borders (Alba et al., 2020; Nagy et al., 2020). The long term use of special groups of antimicrobial substances might have resulted in selection pressure and increased emergence of particular bacterial organisms (Nógrády et al., 2007, 2012). However, it is also stated that antimicrobial usage is not always linked to a higher Salmonella prevalence (Asai et al., 2007). The acquisition of the megaplasmid pESI does not result in a significant burden to its hosts as it is presented only as a single copy in the bacteria genome, therefore, it does not seem to limit the dissemination of the organisms (Aviv et al., 2016).

Production of fimbriae and the ability to form biofilms are discussed as factors enabling a long term persistence of Salmonella organisms at poultry farms. The gene fyuA (Schubert et al., 1998) together with the genes irp1 and irp2 are involved in biofilm formation (Hancock et al., 2008). In this study, gene irp1 was found together with irp2 in all strains that carry the pESI-like plasmid suggesting a possible role in persistence of S. Infantis organisms. However, the association of yersiniabactin and biofilm in serovar Infantis has not been yet wide studied in contrast with other microorganisms as in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) (Zamani and Salehzadeh, 2018). It has been demonstrated before a higher biofilm formation for pESI positive strains (Aviv et al., 2014). Besides, very recently, it has been demonstrated a higher cell adhesion of S. Infantis compared with other serovars. Resistance to heavy metals or biocides like QACs might also play a role in the emergence of S. Infantis. The gene qacEdelta1 (Chuanchuen et al., 2007), located on pESI-like megaplasmids codes for resistance against QACs and was found in this study exclusively in strains from the 2010s. On the other hand, detailed analysis of the sequence of pESI-like pESI2747 has revealed not only resistance genes but also virulence genes, toxin/antitoxin systems that as previously described (Aviv et al., 2014; Acar et al., 2017) play a clue role in the emergence of S. Infantis in poultry. However, it is open whether the encoded resistance against disinfectants might contribute to a higher S. Infantis persistence at broiler farms.

In conclusion, broiler derived S. Infantis strains of ST2283 in Germany show similarities to emergent S. Infantis strains from Europe including the possession of the pESI-like megaplasmid which encodes for antimicrobial resistance, virulence genes (fimbrial clusters) and fitness determinants (toxin/antitoxin system) that enhance bacterial adaptability. Therefore, the involvement of the megaplasmid might explain the current spread of these emergent S. Infantis organisms. However, specific reasons for a suspected higher persistence of MLST2283 could not be identified in this study. It seems that S. Infantis persistence in broiler farms is caused by its occurrence in the primary broiler production and ineffective cleaning and disinfection protocols at least for these special clones. Epidemiological studies on the occurrence of S. Infantis ST2283 in the whole broiler production chain and the establishment of effective control measures are essential to prevent these organisms from entering the food chain.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. Sequencing data of this study can be found at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/data/view/PRJEB36784. The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

UM conceived and coordinated the study, performed serotyping and MIC determination, and wrote the manuscript. JL coordinated the study, developed and implemented the bioinformatics pipeline, and wrote the manuscript. SG-S performed the bioinformatics analysis, performed in-depth analysis of the plasmid, and wrote the manuscript. MA-G performed MinION sequencing and data analysis. HT critically read the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank A. Hackbart and S. Keiling for their excellent technical assistance. We thank Dr. I. Szabo (Head of National Reference Laboratory for Salmonella at the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, BfR) for the kind provision of S. Infantis strains. We also thank Dr. Belén Gonzalez-Santamarina for her suggestions regarding the analysis of SPIs and resistance genes.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01741/full#supplementary-material

Mapping coverage of all pESI-like positive strains across the complete genome sequence of plasmid pESI119944.

Tanglegram plot representing the comparison between pESI-like positive strains using the chromosome sequence of S. Infantis ESI119944 (CP047881) (left) as reference and the plasmid pESI119944 sequence (CP047882) as reference (right).

Minimum spanning tree for previously reported emergent S. Infantis clones from Israel (Aviv et al., 2014, 2016), Hungary (Olasz et al., 2015; Wilk et al., 2016, 2017), and Italy (Franco et al., 2015) used in this study based on cgMLST.

S. Infantis genomes for previously reported emergent S. Infantis clones from Israel (Aviv et al., 2014, 2016), Hungary (Olasz et al., 2015; Wilk et al., 2016, 2017), and Italy (Franco et al., 2015) used in this study and their general genome characteristics and genoserotyping.

Specific gene sequences downloaded for the creation of customized databases for Abricate and available databases downloaded. These databases include sequences of genes encoding for Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPIs), fimbrial clusters Ipf and K88-like and pESI encoded fitness determinants as the toxin-antitoxin (T/AT) system (CcdAB and PemKI/MazF), mercury operon and allele sequences for incompatibility groups plasmids IncI1 and IncF for plasmid typing.

Whole Genome Sequencing general characteristics and genoserotyping of the S. Infantis strains from Germany used in this study.

Resistance genes and chromosomal point mutations found among the S. Infantis strains used in this study.

Virulence genes, SPIs, fimbrial cluster genes and fitness genes found among the S. Infantis strains used in this study.

Plasmid replicons, plasmid pMLST typing and genes encoding for plasmid origin of replication found among the S. Infantis strains used in this study.

References

- Acar S., Bulut E., Durul B., Uner I., Kur M., Avsaroglu M. D., et al. (2017). Phenotyping and genetic characterization of Salmonella enterica isolates from Turkey revealing arise of different features specific to geography. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 241, 98–107. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acar S., Bulut E., Stasiewicz M. J., Soyer Y. (2019). Genome analysis of antimicrobial resistance, virulence, and plasmid presence in Turkish Salmonella serovar Infantis isolates. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 307:108275. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2019.108275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alba P., Leekitcharoenphon P., Carfora V., Amoruso R., Cordaro G., Di Matteo P., et al. (2020). Molecular epidemiology of Salmonella Infantis in Europe: insights into the success of the bacterial host and its parasitic pESI-like megaplasmid. Microb. Genom 6. 10.1099/mgen.0.000365 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alikhan N. F., Zhou Z., Sergeant M. J., Achtman M. (2018). A genomic overview of the population structure of Salmonella. PLoS Genet. 14:e1007261. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews S. (2018). FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data”. v. 0.11, 5 Edn Available online at: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed February, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Asai T., Ishihara K., Harada K., Kojima A., Tamura Y., Sato S., et al. (2007). Long-term prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica Serovar Infantis in the broiler chicken industry in Japan. Microbiol. Immunol. 51 111–115. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2007.tb03881.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviv G., Elpers L., Mikhlin S., Cohen H., Vitman Zilber S., Grassl G. A., et al. (2017). The plasmid-encoded Ipf and Klf fimbriae display different expression and varying roles in the virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis in mouse vs. avian hosts. PLoS Pathog. 13:e1006559. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviv G., Tsyba K., Steck N., Salmon-Divon M., Cornelius A., Rahav G., et al. (2014). A unique megaplasmid contributes to stress tolerance and pathogenicity of an emergent Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis strain. Environ. Microbiol. 16 977–994. 10.1111/1462-2920.12351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviv G., Rahav G., Gal-Mor O. (2016). Horizontal transfer of the Salmonella enterica serovar infantis resistance and virulence plasmid pESI to the gut microbiota of warm-blooded hosts. mBio 7:e01395-16. 10.1128/mBio.01395-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A. A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A. S., et al. (2012). SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19 455–477. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnhart M. M., Chapman M. R. (2006). Curli biogenesis and function. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60 131–147. 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beceiro A., Tomas M., Bou G. (2013). Antimicrobial resistance and virulence: a successful or deleterious association in the bacterial world? Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 26 185–230. 10.1128/CMR.00059-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogomazova A. N., Gordeeva V. D., Krylova E. V., Soltynskaya I. V., Davydova E. E., Ivanova O. E., et al. (2019). Mega-plasmid found worldwide confers multiple antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella Infantis of broiler origin in Russia. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 319:108497. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2019.108497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A., Hasman H. (2020). PlasmidFinder and in silico pMLST: identification and typing of plasmid replicons in whole-genome sequencing (WGS). Methods Mol. Biol. 2075 285–294. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9877-7_20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A., Zankari E., Garcia-Fernandez A., Voldby Larsen M., Lund O., Villa L., et al. (2014). In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 3895–3903. 10.1128/AAC.02412-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Dong N., Chan E. W., Chen S. (2019). Transmission of ciprofloxacin resistance in Salmonella mediated by a novel type of conjugative helper plasmids. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 8 857–865. 10.1080/22221751.2019.1626197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Yang J., Yu J., Yao Z., Sun L., Shen Y., et al. (2005). VFDB: a reference database for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 D325–D328. 10.1093/nar/gki008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuanchuen R., Khemtong S., Padungtod P. (2007). Occurrence of qacE/qacEDelta1 genes and their correlation with class 1 integrons in Salmonella enterica isolates from poultry and swine. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 38 855–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloeckaert A., Praud K., Doublet B., Bertini A., Carattoli A., Butaye P., et al. (2007). Dissemination of an extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase blaTEM-52 gene-carrying IncI1 plasmid in various Salmonella enterica serovars isolated from poultry and humans in Belgium and France between 2001 and 2005. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51 1872–1875. 10.1128/AAC.01514-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E., Rahav G., Gal-Mor O. (2020). Genome Sequence of an Emerging Salmonella enterica Serovar Infantis and Genomic Comparison with Other S. Infantis Strains. Genome Biol. Evol. 12 151–159. 10.1093/gbe/evaa048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA, (2019). The European Union One Health 2018 zoonoses report. EFSA J. 17:e05926. 10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA, (2020). The European Union summary report on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2017/2018. EFSA J. 18:e06007. 10.2903/j.efsa.2020.6007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST, (2018). The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 8.0. [Google Scholar]

- Feldgarden M., Brover V., Haft D. H., Prasad A. B., Slotta D. J., Tolstoy I., et al. (2019a). Using the NCBI AMRFinder tool to determine antimicrobial resistance genotype-phenotype correlations within a collection of NARMS Isolates. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 10.1101/550707 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldgarden M., Brover V., Haft D. H., Prasad A. B., Slotta D. J., Tolstoy I., et al. (2019b). Validating the AMRFinder tool and resistance gene database by using antimicrobial resistance genotype-phenotype correlations in a collection of Isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63:e00483-419 10.1128/AAC.00483-419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer J., Borowiak M., Baumann B., Szabo I., Malorny B. (2017). “Whole-genome sequencing analysis of multidrug-resistant Salmonella Infantis isolatescirculating in the German food-production chain,” in 27th ECCMID, (Vienna: ). [Google Scholar]

- FLI_Bioinfo (2020). WGSBAC. Modules for Genotyping and Characterization of Bacterial Isolates Using Whole-Genome-Sequencing Data”. v2.0, 0 Edn Available online at: https://gitlab.com/FLI_Bioinfo/WGSBAC (accessed February, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Franco A., Leekitcharoenphon P., Feltrin F., Alba P., Cordaro G., Iurescia M., et al. (2015). Emergence of a clonal lineage of multidrug-resistant ESBL-producing Salmonella Infantis transmitted from broilers and broiler meat to humans in Italy between 2011 and 2014. PLoS One 10:e0144802. 10.1371/journal.pone.0144802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimont P., Weill F.-X. (2007). Antigenic Formulae-Grimont-Weill.pdf. WHO Collaborating Center for Reference and Research on Salmonella, 9th Edn Paris: Institut Pasteur. [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich A., Saveliev V., Vyahhi N., Tesler G. (2013). QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29 1072–1075. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gymoese P., Kiil K., Torpdahl M., Osterlund M. T., Sorensen G., Olsen J. E., et al. (2019). WGS based study of the population structure of Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis. BMC Genomics 20:870. 10.1186/s12864-019-6260-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock V., Ferrieres L., Klemm P. (2008). The ferric yersiniabactin uptake receptor FyuA is required for efficient biofilm formation by urinary tract infectious Escherichia coli in human urine. Microbiology 154(Pt 1), 167–175. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/011981-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser E., Tietze E., Helmuth R., Junker E., Prager R., Schroeter A., et al. (2012). Clonal dissemination of Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis in Germany. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 9 352–360. 10.1089/fpd.2011.1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindermann D., Gopinath G., Chase H., Negrete F., Althaus D., Zurfluh K., et al. (2017). Salmonella enterica serovar infantis from food and human infections, Switzerland, 2010–2015: poultry-related multidrug resistant clones and an emerging ESBL producing clonal lineage. Front. Microbiol. 8:1322. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson D. H., Scornavacca C. (2012). Dendroscope 3: an interactive tool for rooted phylogenetic trees and networks. Syst. Biol. 61 1061–1067. 10.1093/sysbio/sys062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley K. A., Bray J. E., Maiden M. C. J. (2018). Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 3:124. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junemann S., Sedlazeck F. J., Prior K., Albersmeier A., John U., Kalinowski J., et al. (2013). Updating benchtop sequencing performance comparison. Nat. Biotechnol. 31 294–296. 10.1038/nbt.2522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolmogorov M., Yuan J., Lin Y., Pevzner P. A. (2019). Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 37 540–546. 10.1038/s41587-019-0072-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist N., Pelkonen S. (2007). Genetic surveillance of endemic bovine Salmonella Infantis infection. Acta Vet. Scand. 49:15. 10.1186/1751-0147-49-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte D. F., Lincopan N., Berman H., Cerdeira L., Keelara S., Thakur S., et al. (2019). Genomic features of high-priority Salmonella enterica serovars circulating in the food production Chain, Brazil, 2000-2016. Sci. Rep. 9:11058. 10.1038/s41598-019-45838-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy T., Szmolka A., Wilk T., Kiss J., Szabo M., Paszti J., et al. (2020). Comparative genome analysis of hungarian and global Strains of Salmonella Infantis. Front. Microbiol. 11:539. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nógrády N., Kardos G., Bistyak A., Turcsanyi I., Meszaros J., Galantai Z., et al. (2008). Prevalence and characterization of Salmonella infantis isolates originating from different points of the broiler chicken-human food chain in Hungary. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 127 162–167. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nógrády N., Kiraly M., Davies R., Nagy B. (2012). Multidrug resistant clones of Salmonella Infantis of broiler origin in Europe. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 157 108–112. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nógrády N., Toth A., Kostyak A., Paszti J., Nagy B. (2007). Emergence of multidrug-resistant clones of Salmonella Infantis in broiler chickens and humans in Hungary. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60 645–648. 10.1093/jac/dkm249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olasz F., Nagy T., Szabo M., Kiss J., Szmolka A., Barta E., et al. (2015). Genome sequences of three Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar infantis strains from healthy broiler chicks in hungary and in the United Kingdom. Genome Announc. 3:e01468-14. 10.1128/genomeA.01468-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate M., Micunovic J., Golob M., Vestby L. K., Ocepek M. (2019). Salmonella infantis in broiler flocks in slovenia: the prevalence of multidrug resistant strains with high genetic homogeneity and low biofilm-forming ability. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019:4981463. 10.1155/2019/4981463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M. N., Dehal P. S., Arkin A. P. (2009). FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26 1641–1650. 10.1093/molbev/msp077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajic A., Keenliside J., McFall M. E., Deckert A. E., Muckle A. C., O’Connor B. P., et al. (2005). Longitudinal study of Salmonella species in 90 Alberta swine finishing farms. Vet. Microbiol. 105 47–56. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross I. L., Heuzenroeder M. W. (2008). A comparison of three molecular typing methods for the discrimination of Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 53 375–384. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00435.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rychlik I., Karasova D., Sebkova A., Volf J., Sisak F., Havlickova H., et al. (2009). Virulence potential of five major pathogenicity islands (SPI-1 to SPI-5) of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis for chickens. BMC Microbiol. 9:268. 10.1186/1471-2180-9-268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salipante S. J., Hall B. G. (2003). Determining the limits of the evolutionary potential of an antibiotic resistance gene. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20 653–659. 10.1093/molbev/msg074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert S., Rakin A., Karch H., Carniel E., Heesemann J. (1998). Prevalence of the “High-Pathogenicity Island” of Yersinia Species among Escherichia coli Strains That Are Pathogenic to Humans. Infect. Immun. 66 480–485. 10.1128/iai.66.2.480-485.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T. (2014a). mlst GitHub. Available online at: https://github.com/tseemann/mlst (accessed February, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T. (2014b). Snippy GitHub. Available online at: https://github.com/tseemann/snippy (accessed February, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T. (2015). Abricate Github. Available online at: https://github.com/tseemann/abricate (accessed February, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T. (2018). Shovill GitHub. Assemble Bacterial Isolate Genomes From Illumina Paired-End Reads. Available online at: https://github.com/tseemann/shovill (accessed February, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Shahada F., Chuma T., Okamoto K., Sueyoshi M. (2008). Temporal distribution and genetic fingerprinting of Salmonella in broiler flocks from southern Japan. Poul. Sci. 87 968–972. 10.3382/ps.2007-00455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szmolka A., Szabo M., Kiss J., Paszti J., Adrian E., Olasz F., et al. (2018). Molecular epidemiology of the endemic multiresistance plasmid pSI54/04 of Salmonella Infantis in broiler and human population in Hungary. Food Microbiol. 71 25–31. 10.1016/j.fm.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaser R., Sovic I., Nagarajan N., Sikic M. (2017). Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. 27 737–746. 10.1101/gr.214270.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B. J., Abeel T., Shea T., Priest M., Abouelliel A., Sakthikumar S., et al. (2014). Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9:e112963. 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk T., Szabo M., Szmolka A., Kiss J., Barta E., Nagy T., et al. (2016). Genome sequences of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar infantis strains from broiler chicks in hungary. Genome Announc. 4:e01400-16. 10.1128/genomeA.01400-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk T., Szabo M., Szmolka A., Kiss J., Olasz F., Nagy B. (2017). Genome sequences of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar infantis strains from hungary representing two peak incidence periods in three decades. Genome Announc. 5:e01735-16. 10.1128/genomeA.01735-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood D. E., Lu J., Langmead B. (2019). Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 20:257. 10.1186/s13059-019-1891-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama E., Ando N., Ohta T., Kanada A., Shiwa Y., Ishige T., et al. (2015). A novel subpopulation of Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis strains isolated from broiler chicken organs other than the gastrointestinal tract. Vet. Microbiol. 175 312–318. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida C. E., Kruczkiewicz P., Laing C. R., Lingohr E. J., Gannon V. P., Nash J. H., et al. (2016). The Salmonella in silico typing resource (SISTR): an open web-accessible tool for rapidly typing and subtyping Draft Salmonella genome assemblies. PLoS One 11:e0147101. 10.1371/journal.pone.0147101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamani H., Salehzadeh A. (2018). Biofilm formation in uropathogenic Escherichia coli: association with adhesion factor genes. Turk J. Med. Sci. 48 162–167. 10.3906/sag-1707-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zankari E., Hasman H., Cosentino S., Vestergaard M., Rasmussen S., Lund O., et al. (2012). Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67 2640–2644. 10.1093/jac/dks261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Mapping coverage of all pESI-like positive strains across the complete genome sequence of plasmid pESI119944.

Tanglegram plot representing the comparison between pESI-like positive strains using the chromosome sequence of S. Infantis ESI119944 (CP047881) (left) as reference and the plasmid pESI119944 sequence (CP047882) as reference (right).

Minimum spanning tree for previously reported emergent S. Infantis clones from Israel (Aviv et al., 2014, 2016), Hungary (Olasz et al., 2015; Wilk et al., 2016, 2017), and Italy (Franco et al., 2015) used in this study based on cgMLST.

S. Infantis genomes for previously reported emergent S. Infantis clones from Israel (Aviv et al., 2014, 2016), Hungary (Olasz et al., 2015; Wilk et al., 2016, 2017), and Italy (Franco et al., 2015) used in this study and their general genome characteristics and genoserotyping.

Specific gene sequences downloaded for the creation of customized databases for Abricate and available databases downloaded. These databases include sequences of genes encoding for Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPIs), fimbrial clusters Ipf and K88-like and pESI encoded fitness determinants as the toxin-antitoxin (T/AT) system (CcdAB and PemKI/MazF), mercury operon and allele sequences for incompatibility groups plasmids IncI1 and IncF for plasmid typing.

Whole Genome Sequencing general characteristics and genoserotyping of the S. Infantis strains from Germany used in this study.

Resistance genes and chromosomal point mutations found among the S. Infantis strains used in this study.

Virulence genes, SPIs, fimbrial cluster genes and fitness genes found among the S. Infantis strains used in this study.

Plasmid replicons, plasmid pMLST typing and genes encoding for plasmid origin of replication found among the S. Infantis strains used in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. Sequencing data of this study can be found at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/data/view/PRJEB36784. The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.