Abstract

Aims and objectives

To examine the feasibility of DAIly NURSE and a nursing intervention to encourage nursing home residents’ daily activities and independence.

Background

Nursing home residents are mainly inactive during the day. DAIly NURSE was developed to change nursing behaviour towards encouraging nursing home residents’ activities and independence by creating awareness. It consists of three components: education, coaching‐on‐the‐job and policy.

Design

A mixed‐method study.

Methods

The feasibility of DAIly NURSE in practice was tested in six psychogeriatric nursing home wards, using attendance lists (reach), evaluation questionnaires (fidelity, dose received and barriers), notes made by the researcher (dose delivered and fidelity) and a focus group interview (dose received and barriers) with nursing home staff (n = 8) at the end of the study.

Results

The feasibility study showed that all three components (education, coaching‐on‐the‐job and policy) were implemented in practice. The attendance rate in the workshops was high (average: 82%). Nursing home staff were satisfied with the workshops (mean score 9 out of 10 points) and agreed that DAIly NURSE was feasible in daily nursing care practice. Recommendations to optimise the feasibility of DAIly NURSE included the following: Add video observations of a specific moment of the day to create awareness of nursing behaviour; educate all nursing staff of the ward during the workshops; and organise information meetings for family members before the start of the intervention. Nursing staff were satisfied with the intervention and provided recommendations for adjustments to the content of the three components. The most important adjustment is the use of video observations to create awareness of nursing staff behaviour.

Conclusions

DAIly NURSE, consisting of education, coaching‐on‐the‐job and policy, is feasible in nursing home practice.

Relevance to clinical practice

DAIly NURSE might help to change nursing behaviour towards encouraging residents’ daily activities and independence.

Keywords: activities of daily living, awareness, behaviour change, encouragement, feasibility studies, independence, nursing home residents, nursing homes, nursing intervention, nursing staff

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

This paper demonstrates the feasibility of a complex nursing intervention, called DAIly NURSE, which supports nursing staff in encouraging nursing home residents’ daily activities and independence.

This paper provides knowledge on supporting elements that strengthen awareness, namely the value of video observations to change nursing behaviour.

1. INTRODUCTION

Nursing home residents spend their day mainly inactive and sedentary (Den Ouden et al., 2015; Van Alphen et al., 2016). This has negative consequences on their quality of life and many other health care outcomes, such as cognitive functioning, incontinence, malnutrition, risk of falling and pressure ulcers (Edvardsson, Petersson, Sjogren, Lindkvist, & Sandman, 2014; Lahmann et al., 2015; Volkers & Scherder, 2011). So far, most activity programs have been aimed at the reduction in inactivity by focusing on physical exercise. A review by Weening‐Dijksterhuis, de Greef, Scherder, Slaets, and van der Schans (2011) provides an overview of several physical exercise interventions to improve health outcomes in nursing home residents. These interventions include components of resistance, strength, balance, flexibility and/or aerobic exercises. Participation in these programs could improve residents’ muscle strength, flexibility, endurance, balance, physical functioning and quality of life (Weening‐Dijksterhuis et al., 2011). The positive effects of exercise a few times a week for a limited amount of time might be small when the residents are still inactive and sedentary during the rest of the day (Ikezoe, Asakawa, Shima, Kishibuchi, & Ichihashi, 2013). In a recent task force report by De Souto Barreto et al. (2016), it is therefore recommended to focus on reducing sedentary behaviour and enhancing activity levels in daily life of all nursing home residents to maintain functioning.

To enhance activity levels in daily life, nursing home residents should be more engaged in daily activities. Daily activities comprise activities of daily living (ADL), such as washing, eating and drinking, mobility and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), such as preparing a meal, setting the table and watering plants (Den Ouden et al., 2015). These (I)ADL seem to be particularly important for nursing home residents, as they are often viewed as meaningful activities (Kleynen, Braun, van Vijven, van Rossum, & Beurskens, 2015). By performing these activities, residents will maintain their functioning and are less care‐dependent (Schüssler, Dassen, & Lohrmann, 2014), which positively influences their sense of dignity (Franklin, Ternestedt, & Nordenfelt, 2006).

2. BACKGROUND

Nursing staff play a key role in encouraging residents’ daily activities and independence (De Souto Barreto et al., 2016; Den Ouden et al., 2016) as they are available 24/7 and spend 54% of their time with providing direct care (Tuinman, de Greef, Krijnen, Nieweg, & Roodbol, 2016). Nursing staff are also in charge of creating a homelike ward climate in which residents could perform their daily activities as they did before they entered the nursing home (Edvardsson, Sandman, & Rasmussen, 2012), such as engaging in preparing meals. A previous study by Kuk, Ouden et al. (2017), in which nursing staff were asked about their perceived behaviour towards encouraging activities, showed that nursing staff reported to encourage residents’ daily activities often, especially ADL. However, observations in a study by Den Ouden et al. (2016) showed that nursing staff took over almost half of residents’ daily activities when they were involved in their activities (e.g., a nurse poured coffee with sugar and milk and even stirred the drink in front of the resident, or a nurse pushed a resident in a wheelchair). This could indicate a difference between perceived and observed behaviour. Therefore, it is essential that nursing staff are aware of their actual behaviour and have the opportunity to encourage residents.

Encouraging nursing home residents can be challenging since nursing staff experience several barriers. Barriers such as care routines and communication and support within the team are strongly associated with the encouragement of activities and independency (Kuk, Zijlstra et al., 2017). In addition, nursing staff experience barriers such as time constraints, expectations of others and residents’ capabilities (Kuk, Zijlstra et al., 2017; Resnick et al., 2008). Nursing interventions should support nursing staff in creating awareness and changing their behaviour towards encouraging nursing home residents’ daily activities and independence.

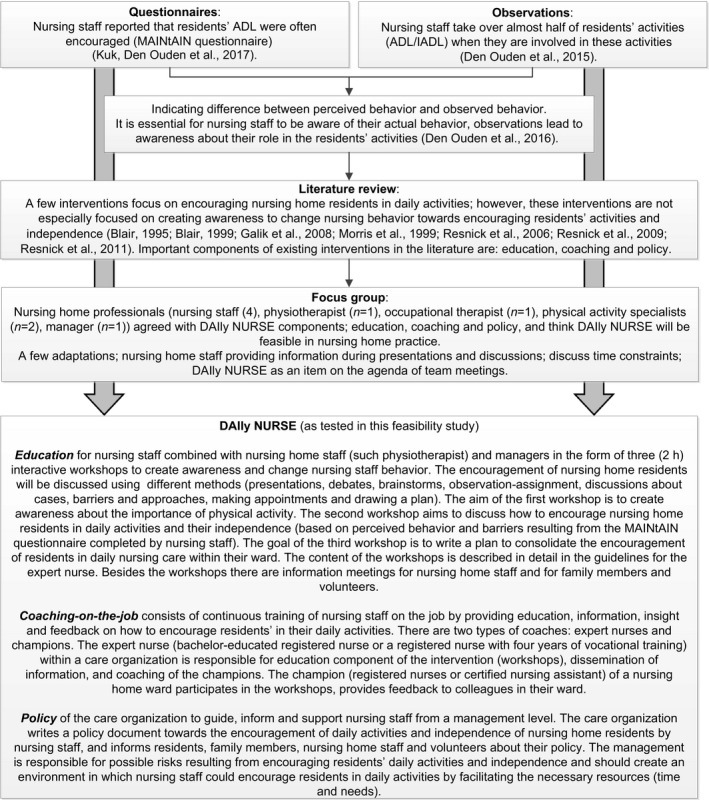

Interventions focusing on changing nursing behaviour towards encouraging nursing home residents in daily activities and their independence are scarce. The limited amount of interventions described in the literature lack effectiveness (Blair, 1995, 1999; Galik et al., 2008; Morris et al., 1999; Resnick, Galik, Gruber‐Baldini, & Zimmerman, 2011; Resnick et al., 2006, 2009). Additionally, these interventions do not focus directly on creating awareness to change nursing behaviour, as emphasised by De Souto Barreto et al. (2016). Education, coaching and policy are important components of existing interventions, as described above, as well as existing interventions on other topics in nursing home care, like physical restraints (Gulpers, Bleijlevens, van Rossum, Capezuti, & Hamers, 2010; Resnick et al., 2011). A combination of different strategies is more useful than a single strategy such as education (Gillespie et al., 2003; Gulpers et al., 2010, 2013; Huizing, Hamers, Gulpers, & Berger, 2009). An example of a multicomponent nursing intervention in this field is “Daily Activities and Independence by NURsing Staff Encouragement” (DAIly NURSE), which aims to change nursing staff behaviour in a way that nursing home residents are encouraged and supported to perform their daily activities as independently as possible during daily nursing practice. This change is supported by creating awareness of their own nursing behaviour towards the encouragement of residents’ daily activities and independence and the possible consequences of their behaviour. The intervention consists of the following three components; education, coaching‐on‐the‐job and policy. The steps of the development, including the main results of each step, and the content of the three components of DAIly NURSE are described in Box 1. DAIly NURSE has not been tested in daily nursing home practice. Therefore, the current study evaluates the feasibility of DAIly NURSE, aiming to optimise and finalise the intervention.

Box 1. Development including main results of each step and content of DAIly NURSE.

1.

3. METHODS

3.1. Study design

This study describes the feasibility testing of DAIly NURSE using a mixed‐methods design, including qualitative and quantitative measures.

3.2. Sample

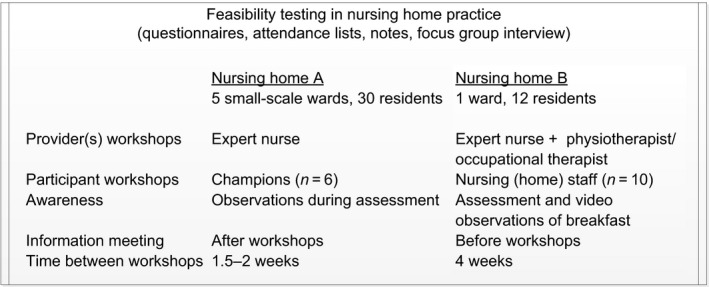

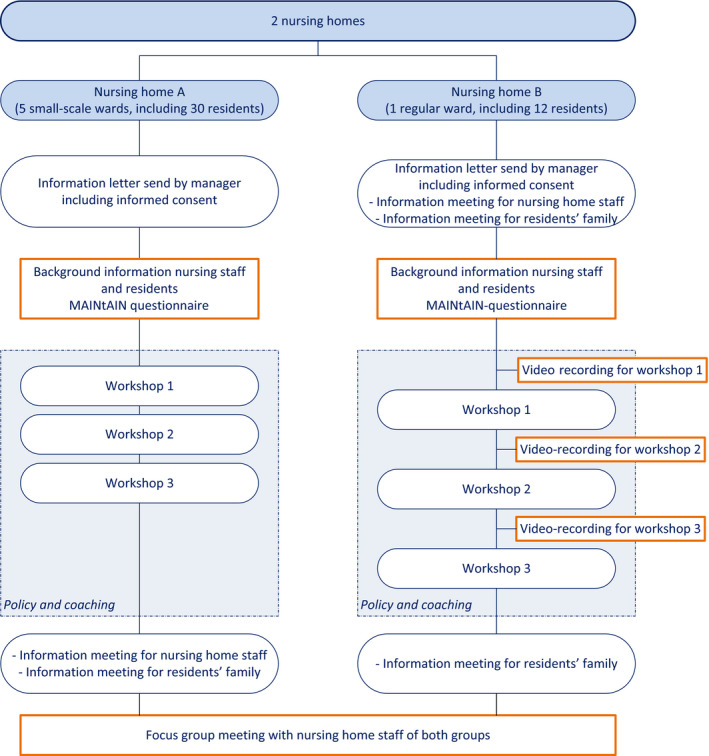

DAIly NURSE was implemented in the psychogeriatric wards (n = 6) of two nursing homes (A and B). The two nursing homes were able to tailor the intervention to the organisation by adapting minor aspects of DAIly NURSE. Therefore, DAIly NURSE was tested in slightly different ways (Figure 1). Nursing home A participated with five small‐scale wards, housing six residents in each ward (n = 30 total). A total of 35 nursing staff were employed in the wards, of whom six champions (n = 6) were appointed to participate in the workshops. The expert nurse was 49 years old and had 11 years of working experience in elderly care and experience with providing education in the field of physical activity within the care organisation. Nursing home B participated with one regular ward of 12 residents (n = 12 total); the whole team of nursing staff (n = 7) was involved in the workshops; in addition, other nursing home staff, such as the physiotherapist, were involved. The expert nurse in nursing home B was 36 years old and had 20 years of working experience in elderly care. All nursing staff participating in the workshops of this study were certified nurse assistants (CNAs), with 3 years of secondary‐vocational training; the expert nurses in both nursing homes were registered nurses (RNs), with 4 years of secondary‐vocational training or bachelor education (Verkaik et al., 2011). Both nursing homes used an observation–assignment between the workshops to create awareness of residents’ capabilities in (I)ADL. This observation–assignment consisted of a list of daily activities divided into several steps. Nursing staff score whether a resident was able to perform each activity independently, with support, or not at all; furthermore, they observe and score whether the resident actually does perform the activity (independently, with support or not). This observation–assignment creates awareness of a possible difference between what a resident can do and what the resident actually does. In addition, video recordings of breakfast times were shown in the workshops of nursing home B to create awareness. Participants of the focus group interview were nursing home staff of both nursing homes (nursing home A n = 5, nursing home B n = 3). Most of the focus group participants were nursing staff (n = 7), while one had a background as an occupational therapist (n = 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of participating nursing homes; differences and similarities

3.3. Measurements

The feasibility of DAIly NURSE in nursing home practice was defined according to the framework of Saunders, Evans, and Joshi (2005): Dose delivered, fidelity, dose received‐exposure, dose received‐satisfaction, reach and barriers were assessed using self‐administered evaluation questionnaires, attendance lists, notes of the workshops and a focus group interview (Table 1). Self‐administered evaluation questionnaires containing questions (10‐point Likert scale and open‐ended) about the clarity of the information received, sufficiency of time for discussions, satisfaction with the expert nurse, possibilities for improvement, etc. were used to gather information about the fidelity, dose received‐exposure, dose received‐satisfaction and barriers. Attendance lists were used to obtain insight into the reach of DAIly NURSE. Notes about the discussions during each workshop and information meeting were made by the researcher to measure dose delivered and fidelity. Participants of the feasibility study from both nursing homes (n = 8) discussed the feasibility (dose received‐exposure, dose received‐satisfaction and barriers) of DAIly NURSE in nursing care practice during the focus group interview. During this meeting, the experiences with the three components of DAIly NURSE, and the similarities and differences in the implementation of DAIly NURSE in nursing practice between the different nursing homes were discussed. Topics considered were, for example, participants of the education, themes lacking in the workshops, focus on activities during a specific moment of the day, such as breakfast, information meetings for nursing staff and for residents’ family, how to inform and involve family and volunteers, planning, creating awareness using video observations and the implementation plan.

Table 1.

Measures of feasibility

| Operationalisation | Measurement instrument | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire | Attendance list | Notes | Focus group interview | ||

| Dose delivered | The extent to which all three components were delivered | x | |||

| Fidelity | The extent to which DAIly NURSE was implemented as planned | x | x | ||

| Dose received‐exposure | The extent to which nursing staff used the assignment | x | x | ||

| Dose received‐satisfaction | Satisfaction of nursing home staff regarding the components | x | x | ||

| Reach | Proportion of the target population that attended the workshops | x | |||

| Barriers | Barriers experienced by nursing home staff during the implementation | x | x | ||

Additionally, to obtain insight into the nursing home environment, background information of the nursing home residents and nursing staff participating in the workshops was gathered. Data collected on nursing home residents included date of birth, date of admission to the nursing home, gender, mobility (mobile, wheelchair‐dependent or bedridden), physical functioning (Barthel Index; De Haan et al., 1993) and cognitive functioning (Cognitive Performance Scale; Morris et al., 1994). Characteristics of nursing staff collected were as follows: date of birth, gender, level of education, professional level, years of working experience and hours of working in the ward per week. Further, nursing staff completed the MAINtAIN questionnaire (Kuk, Zijlstra, Bours, Hamers, & Kempen, 2016) prior to the workshops to obtain insight into their perceived behaviour towards and barriers to encouraging residents’ activities. This questionnaire consists of 19 items about perceived behaviour to encourage ADL, household and more general activities, and 33 items to measure barriers related to resident, professional, social or organisational level. The MAINtAIN questionnaire is validated on its content and positively tested on its usability. For each item, nursing staff rate to what extent that activity was encouraged or that barrier was experienced on their ward (“on my ward …”). Each item can be scored on a 9‐point scale, ranging from “never” to “always” or “completely disagree” to “completely agree” (Kuk et al., 2016).

3.4. Procedure

At the start of the implementation in nursing home practice, background characteristics of participating nursing home residents and nursing staff were gathered using questionnaires. Nursing staff completed the questionnaires about the residents based on the residents’ files, as well as completing the questionnaires about themselves. The expert nurse receives the manual to lead the workshops. This manual contains a detailed description of the workshops, the themes that should be discussed, a global time schedule for each workshop, handouts and background information for the expert nurse. Before the start of the study, the principal researcher met with the expert nurse to deliver the manual and shortly discuss it, but did not provide a special training to the expert nurse. During each workshop and information meeting, the principal researcher made notes, and at the end of each session, the participants signed the attendance list and completed evaluation questionnaires. The results of the evaluation questionnaires provided input for the discussion of barriers and suggestions for improvement during the focus group interview. The interview took place after the implementation in nursing home practice. The principal researcher discussed the differences between the two nursing homes with the participants with the aim of reaching a consensus about adjustments to the intervention to be made in order to optimise the feasibility of DAIly NURSE and finalise its format.

3.5. Statistical analyses

The quantitative data from the evaluation questionnaires and background characteristics were analysed using descriptive statistics in SPSS (version 24). Differences in background characteristics between the two nursing homes were determined using an independent t test for the continuous variables and a chi‐square test for the categorical variables. Qualitative data from open‐ended questions were summarised and discussed in the focus group interview. The focus group interview was audio‐taped and summarised by the principal author guided by the formulated questions from beforehand. Recommendations for improving the intervention were extracted from the summary.

3.6. Ethical considerations

The study protocol of the feasibility study was approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee of Zuyderland Zuyd (16‐N‐131) in 2016. Nursing home directors provided permission to conduct the feasibility study. Legal representatives of each nursing home resident received an information letter and were asked to provide informed consent to gather background data about the resident. Further, the director of nursing home B asked the legal representatives of the nursing home residents to give permission for the video recordings during the information meeting for family members; if they were not present, they were contacted by telephone. Nursing home staff participated voluntarily and consented to the recording of the focus group interviews.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Nursing home environment

Background characteristics of the residents and the nursing staff involved in the workshops can be found in Table 2. In nursing home A, 20 representatives replied to the informed consent letter, and 14 of them gave their informed consent. In nursing home B, nine representatives replied, and all gave informed consent. Nursing staff completed the questionnaires of 13 and 7 residents, respectively. Nursing staff involved in the workshops (n = 13) completed the questionnaires about their characteristics and the MAINtAIN questionnaire. No significant differences were found between the nursing homes in background characteristics of the group of nursing home residents and nursing staff participating in the workshops. Merely, results of the MAINtAIN‐behaviors questionnaire indicate that IADL were significantly more encouraged in the wards of nursing home A than in nursing home B. Important barriers for nursing staff to encouraging activities and independence of nursing home residents of both nursing homes, according to the MAINtAIN‐barriers, were as follows: Nursing staff felt that it was not their responsibility to inform informal caregivers about the importance of residents’ daily activities and independence; their manager did not communicate this importance; and nursing staff did not feel they were able to encourage residents to perform daily activities more independently. Further, in nursing home A, nursing staff experienced a lack of opportunities to attend courses as being the most important barrier, whereas, in nursing home B, nursing staff felt that it was not relevant for nursing home residents to perform daily activities independently.

Table 2.

Background characteristics of the nursing home residents and nursing staff participating in the workshops

| Nursing home A | Nursing home B | |

|---|---|---|

| Residents (n) | 13 | 7 |

| Average age in years (SD) | 84 (9) | 84 (9) |

| Female, % | 85 | 86 |

| Average length of stay in months (SD) | 33 (28) | 31 (39) |

| Mobile, % | 75 | 86 |

| Average physical functioning (SD)a | 9.3 (7.1) | 11.4 (4.9) |

| Cognitive functioning (SD)b | 3.6 (1.9) | 2.8 (2.0) |

| Nursing staff in the workshops (n) | 6 | 7 |

| Age in years (SD) | 43 (12) | 33 (10) |

| Gender (% female) | 100% | 86% |

| Professional level | 100% CNA | 100% CNA |

| Working experience (years) | ||

| In elderly care | 18 | 4 |

| In the ward | 7 | 3 |

| Working hours per week | 25 | 25 |

| MAINTAIN‐behaviorsc | ||

| ADL | 8.0 (0.8) | 6.6 (1.4) |

| IADL* | 7.0 (0.8) | 3.6 (2.0) |

| Miscellaneous | 7.9 (1.3) | 7.4 (1.3) |

ADL, activities of daily living; CNA, certified nurse assistant; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

aPhysical functioning: Barthel Index range 0–20 (a lower score indicates an increased disability; De Haan et al., 1993). bCognitive functioning: Cognitive Performance Scale range 0–6 (a higher score indicates a more severe cognitive impairment; Morris et al., 1994). cMAINtAIN‐behaviors: range 1–9 (a higher score indicates more encouragement; Kuk, Ouden et al., 2017).

*Significant difference between nursing homes (p < 0.05).

4.2. Dose delivered

All three components of the intervention DAIly NURSE (education, coaching‐on‐the‐job and policy) were delivered in both nursing homes. The three 2‐hour workshops of the educational component were facilitated and scheduled by the nursing home management. Further, the management appointed coaches (expert nurse and champions). Nursing home staff and family members were informed about the study by information letters of the management and were informed about the importance of physical activity and the intervention during workshops or information meetings. The manager explained the institutional policy with regard to the encouragement of daily activities and independence of nursing home residents during one of the workshops and during information meetings. The expert nurse led the workshops following the manual. The coaching‐on‐the‐job was provided by the expert nurse and champions.

4.3. Fidelity

Figure 2 provides an overview of the provided components in the two nursing homes. In nursing home A, the expert nurse led all three workshops and invited guest speakers—the manager, occupational therapist and psychologist; the champions participated. In nursing home B, the expert nurse provided all three workshops together with an occupational therapist and a physiotherapist. The whole team of nursing staff participated (n = 7). All sorts of different themes as described in the manual were addressed in the workshops in both nursing homes, including policy explained by a manager; nursing behaviour and experienced barriers were discussed based on the results of the MAINtAIN questionnaire; and at the end of the three workshops, an implementation plan was made to continue encouraging residents in daily activities and independence. Nursing staff felt support of managers, by their attendance during the workshops and by their presentation of the policy regarding the encouragement of residents’ daily activities and independence. In nursing home A, the workshops were spread over a total period of a month, with from 1.5–2 weeks between the workshops. The workshops in nursing home B were once a month, with 4 weeks between them. Nursing staff in nursing home A were informed about the study by an information letter before the start of the intervention. Furthermore, after the workshops, nursing staff who did not attend them were informed during a team meeting about the implementation plan that was made by the champions in the workshops. During this meeting, the expert nurse provided information about the implementation plan. The champions attended this meeting as well and complemented the expert nurse with their experiences. Family members of residents in this nursing home were informed about the study by a letter, in which they were invited to an information meeting provided by the expert nurse after the start of the intervention (after workshops). In nursing home B, nursing home staff and family members were informed by the nursing home director about the study during information meetings before the start of the intervention, and family members were invited to a meeting at the end of the study period to discuss the experiences with DAIly NURSE. The expert nurse attended all information meetings. Both care organisations have a policy document regarding their vision on the encouragement of daily activities and independence of nursing home residents.

Figure 2.

Overview of the provided components in the two nursing homes [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4.4. Dose received‐exposure

In nursing home A, four of the six participating nursing staff completed the observation–assignment before the second workshop, and in nursing home B, five of the seven nurses did so. According to the self‐administered questionnaires, the nursing staff expressed different experiences with the assignment. One participant indicated that the assignment had no added value, whereas the others reported that the assignment led to more awareness of the capability of the residents. For example, the assignment showed that a resident was able to set the table independently, but this activity was always performed by nursing staff. The resident could be encouraged to participate in setting the table, and by making personal contact, providing compliments and confidence. the resident was motivated to set the table. Another resident was put in a wheelchair when she went outside, whereas she was able to walk with her rollator. Additionally, a resident was washed by nursing staff, whereas he was able to wash his own face, arms and breast, especially with some supervision or verbal instructions. The participants indicated that the assignment was difficult to carry out; therefore, the assignment should be better explained and more attention to the assignment was needed during the workshop. Furthermore, the participants in nursing home A did not have much time to complete the assignment. Nevertheless, participants agreed that the assignment led to more awareness of the capability of residents.

4.5. Dose received‐satisfaction

The participants of the workshops were satisfied with the educational component of DAIly NURSE; they gave, on average, a score of 9 out of 10 for their satisfaction with the workshops. Participants were satisfied with the duration of each workshop and reported that there was enough time for discussions and questions. Further, the participants mentioned that they liked the openness of the other participants, how they worked together during the workshops and appreciated the input of guest speakers. In nursing home B, the participants of the workshops mentioned that the video observations were very valuable in creating awareness: They indicated they had become more aware of the daily activities of nursing home residents and their role in these activities when observing a specific moment (breakfast) than after conducting the assignment in which they observed several ADL and IADL of a resident. For example, coffee and tea with sugar and milk were poured often in the kitchen, and even the drinks were stirred by the nursing staff. If a resident prepared their own sandwich, all requirements were placed in front of this person by nursing staff, whereas nursing staff could encourage the resident to collect the requirements in the kitchen and put them on the table himself. Video observations also provided insight into the context in which the residents perform daily activities, for example, when nursing staff run around the table with bread, spreads, medicine etc., as observed in the videos, residents were distracted from their meal. During the focus group interview, nursing staff of nursing home A stated that they would have liked to have seen themselves and their colleagues on video to observe their behaviour and to create awareness. Furthermore, the participants of the focus group interview agreed that focusing on a specific moment during the day (e.g., breakfast) could help nursing staff to start changing their behaviour and extend their encouragement to other moments during the day. Mealtimes are important occasions in the day in the nursing home, and many daily activities could take place during that time. The participants of the information meetings for nursing staff were satisfied (8 out of 10 on average); they felt the information was clear, and it made the participants aware of the importance of daily activities and independence for nursing home residents.

Coaching‐on‐the‐job was difficult to evaluate since coaching should take place after the workshops in particular. Nursing staff of both nursing homes were satisfied with the expert nurse who provided the workshops (score range 8–10). Coaches indicated that it would be helpful to schedule reflection meetings to discuss experiences and evaluate the intervention once every (other) month. Nursing staff indicated that they felt supported by the policy and by the management who facilitated the workshops, attended a workshop and provided compliments.

4.6. Reach

The average attendance rate in the workshops was 82%. In nursing home A, at least five of the six champions attended each workshop (83%); in the second workshop, all champions were present (100%). In nursing home B, six of the team of seven nursing staff participated (86%) in workshops 1 and 2, and the last workshop had the lowest attendance rate (57%) due to illness (n = 2) and a conflicting appointment (n = 1). The information meetings for families had a low attendance rate. The meeting in nursing home A had only three visitors (10%), and the meeting in nursing home B had five participants (42%). During the focus group meeting, participants agreed that the best moment to inform family members, residents and volunteers is before the start of DAIly NURSE. They will become curious, and it is essential to make them aware of the importance of daily activities and the positive influences.

4.7. Barriers

Barriers experienced by nursing home staff during the implementation differed in the nursing homes. In nursing home A, the champions participating in the workshops experienced resistance from colleagues who did not attend the workshops. Therefore, it is recommended to invite the whole team of nursing staff to attend the workshops to prevent this from happening. By educating the whole team in the workshops, coaching‐on‐the‐job will be easily integrated into daily nursing practice. During the workshops, volunteers could be asked to stay on the ward or nursing staff of other wards could cover. If all nursing staff participate in the workshops, no information meeting is necessary; however, nursing staff need to be informed by the management about DAIly NURSE before the start of the intervention. The time between workshops was too short in nursing home A; participants need more time between the workshops to do the observation–assignment and try to encourage residents in daily activities, so that their experiences can be discussed with other participants in the next workshop. Therefore, the time between two workshops should be 3–4 weeks; this will provide participants with enough time to conduct the assignment and change their behaviour and discuss their experiences during the following workshop. In nursing home B, no barriers were mentioned in the evaluation questionnaires.

4.8. Final version of DAIly NURSE

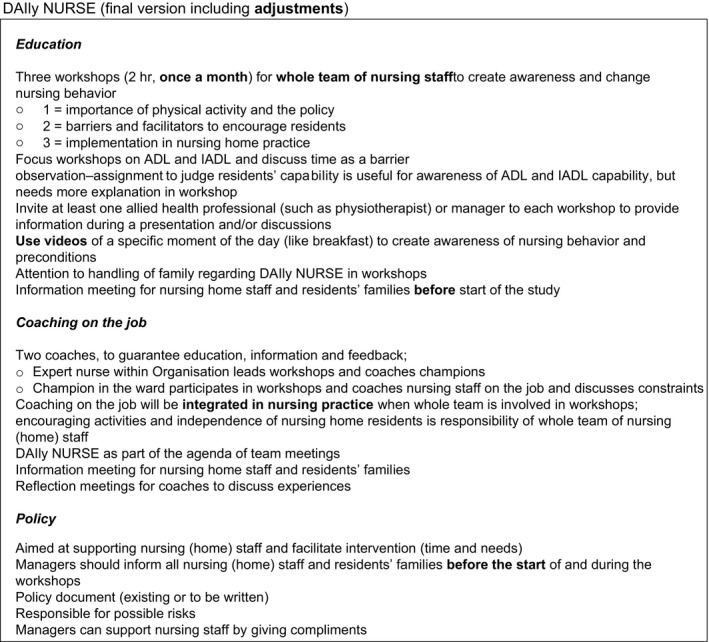

The experiences with DAIly NURSE in nursing home practice and recommendations for the adjustments were used to make the intervention as feasible as possible in nursing home practice. DAIly NURSE consists of education, coaching‐on‐the‐job and policy. Education consists of three interactive workshops for the whole team of nursing staff, to create awareness and discuss the encouragement of (I)ADL in nursing home residents, and an information meeting for family members and volunteers before the start of DAIly NURSE. Coaching on the job is provided by an expert nurse and champions to continue education, awareness and carry on encouraging nursing home residents for all nursing (home) staff. Policy supports all nursing (home) staff, and managers should inform them about DAIly NURSE before the start of the workshops. The final version of DAIly NURSE, including the adjustments, is described in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The content of DAIly NURSE including adjustments after the feasibility study

5. DISCUSSION

This study showed that the nursing intervention DAIly NURSE, including the three components, education, coaching‐on‐the‐job and policy, is feasible in nursing home practice. DAIly NURSE brings policy into practice by facilitating education and coaching. The policy supports nursing staff in changing their behaviour, and managers spread information towards (in)formal caregivers. The coaches learn from each other and create awareness during the workshops. Nursing staff were satisfied with the workshops and the expert nurse who provided the workshops, and the attendance rate in the workshops was high. A few barriers were experienced, such as the reluctance of colleagues who did not attend the workshops. Recommendations for small adjustments about the content were provided by nursing staff to improve the feasibility of DAIly NURSE.

DAIly NURSE is a complex nursing intervention according to the MRC framework (Craig et al., 2008). It consists of interacting components and has different target groups including management, nursing (home) staff and nursing home residents. The MRC framework is a well‐known framework that is most used to develop and evaluate complex interventions, provided by the Medical Research Council (MRC). The framework used consists of four phases; development, feasibility and piloting, evaluation and implementation phase (Craig et al., 2008). Different steps were taken in the development phase of the MRC framework, namely questionnaires, observations, literature review and focus group interview. The current study was part of the testing and piloting phase of the MRC framework (Craig et al., 2008). Feasibility studies do help to understand whether interventions can be implemented in practice and what should be adjusted to make the intervention (more) applicable (Bowen et al., 2009). Attempting to tackle problems before the actual implementation is of major importance.

In the current study, the feasibility of DAIly NURSE was evaluated using the framework of Saunders et al. (2005). This framework provides insight into the process, and data on dose delivered and received, fidelity, reach and barriers were included. Several factors influence the process: Each nursing home, staff member and resident is different; therefore, it is essential for nursing care practice to tailor the intervention to the context. Interventions will be most feasible if tailored to the context instead of being completely standardised (Craig et al., 2008); therefore, the content of the components of DAIly NURSE should be adaptable. For example, the discussions in the workshops are based on the most important barriers, as shown by the results of the MAINtAIN questionnaire (Kuk et al., 2016), and provide input for the implementation plan, which should match the needs of nursing staff, and an awareness of residents’ capabilities helps nursing staff to tailor their support. Furthermore, nursing home staff should work together, should use knowledge from different sources and disciples, and should take into account the context (Raad voor Volksgezondheid en Samenleving, 2017).

Despite the differences in the testing of DAIly NURSE in the two nursing homes, the participants of both nursing homes agreed with the adjustments to make DAIly NURSE as feasible as possible in nursing care practice. The most important adjustment in the content of DAIly NURSE is the use of video observations of breakfast times during the workshops. Nursing staff in nursing home B experienced the videos as a positive feedback opportunity; reflection of own practice during a specific moment (breakfast) led to awareness and knowledge of their own behaviour (Hansebo & Kihlgren, 2001). Focusing on activities during mealtimes is essential in nursing homes, since mealtimes are the most important moments during the day for residents (Watkins, Goodwin, Abbott, Hall, & Tarrant, 2017). Nursing staff can positively influence residents’ quality of life by encouraging residents’ autonomy and social interactions during mealtimes (Watkins et al., 2017). Observations help nursing staff to create awareness of residents’ daily activities and their own role in residents’ dependency (Den Ouden et al., 2016). In addition, the videos showed restlessness in the living room caused by the noise of the radio and machines, and by visits. Nursing staff of nursing home A, who did not use video observations, agreed in the focus group that videos would be of added value; therefore, the video observations of breakfast were added to the DAIly NURSE workshops, in addition to the capability list that is focused on ADL and IADL. In addition to the positive experiences of nursing staff with the video observations, these recordings could be used to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention in future studies.

Although it is emphasised that remaining active is of major importance, interventions that actually focus on encouraging daily activity are scarce (Resnick, Galik, & Boltz, 2013). Nevertheless, activity and mobility have been described as one of the fundamental care needs by nurse scientists, such as Henderson (1960) and Kitson, Conroy, Wengstrom, Profetto‐McGrath, and Robertson‐Malt (2010). It is seen as one of the basic nursing care activities that are often undervalued by nursing staff and perceived as fulfilled (Kuk, Ouden et al., 2017). Fulfilling these basic care needs, such as encouraging and supporting mobility, enables a person's ability to interact with others and participate in their living environment. Therefore, optimising opportunities for older residents to maintain independent mobility as long as possible and reducing inactivity is a key role of nursing staff (Henderson, 1960).

This study has a few limitations. A small sample of psychogeriatric nursing home wards was included in this study. The two nursing homes implemented DAIly NURSE in two different ways. It would be preferable if both groups had the same experiences with and without video observations and both some of the team and the whole team were trained. However, here the differences could be discussed and consensus was reached during the focus group. The nursing home in which only the champions were part of the workshops, instead of the whole team of nursing staff, agreed to educate the whole team with workshops to prevent the resistance of colleagues. It remains unknown whether educating the whole team is most effective in supporting nursing staff to change their behaviour towards encouraging residents’ daily activities and independence. Another limitation is that coaching‐on‐the‐job was hard to evaluate in this study, since the coaching should develop particularly in the period after the workshops, including reflection meetings for champions. Furthermore, not all elements of the framework were explicitly evaluated (recruitment and context). The management recruited the participants of the workshops and no contextual factors were identified during the study. Nevertheless, the data collected regarding the feasibility of the intervention provide enough useful information about the necessary adjustments to make DAIly NURSE feasible in nursing home practice.

DAIly NURSE was tested in nursing home practice and finalised based on the recommendations of nursing home staff who have experiences with the intervention in nursing care practice. Both the development and the feasibility testing were conducted in close collaboration with nursing home staff to develop an intervention that is feasible in nursing home practice (Power et al., 2005). This article described the feasibility and provided insight into the content of the components of DAIly NURSE. Most existing studies do not describe the details of the content of the intervention. This insight into the content as well as the feasibility of the intervention is needed to understand the possible effects of an intervention (Blankevoort et al., 2010). Future studies will focus on the effectiveness of DAIly NURSE from the perspective of both the nursing staff and the residents.

6. CONCLUSION

DAIly NURSE is a feasible nursing intervention to encourage nursing home residents in their daily activities and independence. DAIly NURSE consists of three components: education, coaching‐on‐the‐job and policy. Based on this feasibility study, small adjustments were made to the content of these components to improve feasibility of DAIly NURSE.

7. RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

Nursing home residents are inactive, whereas it is well known that remaining active is of major importance. Nursing staff providing care 24/7 play an essential role in the activity levels of nursing home residents. Nursing interventions that actually focus on encouraging daily activity are scarce. DAIly NURSE is such a nursing intervention aiming to create awareness of the importance of residents’ daily activities and the role of nursing staff in the dependency of nursing home residents. This intervention is feasible in nursing home practice and might help nursing staff to change their behaviour towards encouraging residents’ daily activities and independence.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research project was funded by ZonMw (project number: 520001003), the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development.

den Ouden M, Zwakhalen SMG, Meijers JMM, Bleijlevens MHC, Hamers JPH. Feasibility of DAIly NURSE: A nursing intervention to change nursing staff behaviour towards encouraging residents’ daily activities and independence in the nursing home. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:801–813. 10.1111/jocn.14677

REFERENCES

- Blair, C. E. (1995). Combining behavior management and mutual goal setting to reduce physical dependency in nursing home residents. Nursing Research, 44, 160–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair, C. E. (1999). Effect of self‐care ADLs on self‐esteem of intact nursing home residents. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 20, 559–570. 10.1080/016128499248367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankevoort, C. G. , van Heuvelen, M. J. , Boersma, F. , Luning, H. , de Jong, J. , & Scherder, E. J. (2010). Review of effects of physical activity on strength, balance, mobility and ADL performance in elderly subjects with dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 30, 392–402. 10.1159/000321357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, D. J. , Kreuter, M. , Spring, B. , Cofta‐Woerpel, L. , Linnan, L. , Weiner, D. , … Fernandez, M. (2009). How we design feasibility studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36, 452–457. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, P. , Dieppe, P. , Macintyre, S. , Michie, S. , Nazareth, I. , Petticrew, M. , & Medical Research Council Guidance (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. British Medical Journal, 337, a1655 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haan, R. , Limburg, M. , Schuling, J. , Broeshart, J. , Jonkers, L. , & van Zuylen, P. (1993). Clinimetric evaluation of the Barthel Index, a measure of limitations in dailly activities [in Dutch]. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde, 137, 917–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souto Barreto, P. , Morley, J. E. , Chodzko‐Zajko, W. , H. Pitkala, K. , Weening‐Djiksterhuis, E. , Rodriguez‐Mañas, L. , … International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics – Global Aging Research Network (IAGG‐GARN) and the IAGG European Region Clinical Section (2016). Recommendations on physical activity and exercise for older adults living in long‐term care facilities: A taskforce report. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17, 381–392. 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Ouden, M. , Bleijlevens, M. H. C. , Meijers, J. M. M. , Zwakhalen, S. M. G. , Braun, S. M. , Tan, F. E. S. , & Hamers, J. P. H. (2015). Daily (In)activities of nursing home residents in their wards: An observation study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 16, 963–968. 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Ouden, M. , Kuk, N. O. , Zwakhalen, S. M. , Bleijlevens, M. H. , Meijers, J. M. , & Hamers, J. P. (2016). The role of nursing staff in the activities of daily living of nursing home residents. Geriatric Nursing, 38, 225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsson, D. , Petersson, L. , Sjogren, K. , Lindkvist, M. , & Sandman, P. O. (2014). Everyday activities for people with dementia in residential aged care: Associations with person‐centredness and quality of life. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 9, 269–276. 10.1111/opn.12030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsson, D. , Sandman, P. O. , & Rasmussen, B. (2012). Forecasting the ward climate: A study from a dementia care unit. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 1136–1144. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03720.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, L.‐L. , Ternestedt, B.‐M. , & Nordenfelt, L. (2006). Views on dignity of elderly nursing home residents. Nursing Ethics, 13, 130–146. 10.1191/0969733006ne851oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galik, E. M. , Resnick, B. , Gruber‐Baldini, A. , Nahm, E. , Pearson, K. , & Pretzer‐Aboff, I. (2008). Pilot testing of the restorative care intervention for the cognitively impaired. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 9, 516–522. 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, L. D. , Gillespie, W. J. , Robertson, M. C. , Lamb, S. E. , Cumming, R. G. , & Rowe, B. H. (2003). Interventions for preventing falls in elderly people. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CD000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulpers, M. J. , Bleijlevens, M. H. , Ambergen, T. , Capezuti, E. , van Rossum, E. , & Hamers, J. P. (2013). Reduction of belt restraint use: Long‐term effects of the EXBELT intervention. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61, 107–112. 10.1111/jgs.12057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulpers, M. J. , Bleijlevens, M. H. , van Rossum, E. , Capezuti, E. , & Hamers, J. P. (2010). Belt restraint reduction in nursing homes: Design of a quasi‐experimental study. BMC Geriatrics, 10, 11 10.1186/1471-2318-10-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansebo, G. , & Kihlgren, M. (2001). Carers’ reflections about their video‐recorded interactions with patients suffering from severe dementia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 10, 737–747. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2001.00558.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, V. (1960). Basic principles of nursing care. Geneva: International Council of Nurses. [Google Scholar]

- Huizing, A. R. , Hamers, J. P. , Gulpers, M. J. , & Berger, M. P. (2009). A cluster‐randomized trial of an educational intervention to reduce the use of physical restraints with psychogeriatric nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57, 1139–1148. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02309.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikezoe, T. , Asakawa, Y. , Shima, H. , Kishibuchi, K. , & Ichihashi, N. (2013). Daytime physical activity patterns and physical fitness in institutionalized elderly women: An exploratory study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 57, 221–225. 10.1016/j.archger.2013.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitson, A. , Conroy, T. , Wengstrom, Y. , Profetto‐McGrath, J. , & Robertson‐Malt, S. (2010). Defining the fundamentals of care. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 16, 423–434. 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01861.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleynen, M. , Braun, S. M. , van Vijven, K. , van Rossum, E. , & Beurskens, A. J. (2015). The development of the MIBBO: A measure of resident preferences for physical activity in long‐term care settings. Geriatric Nursing, 36, 261–266. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuk, N. O. , den Ouden, M. , Zijlstra, G. A. R. , Hamers, J. P. H. , Kempen, G. I. J. M. , & Bours, G. J. J. W. (2017). Do nursing staff encourage functional activity among nursing home residents? A cross‐sectional study of nursing staff perceived behaviors and associated factors. BMC Geriatrics, 17, 18 10.1186/s12877-017-0412-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuk, N. O. , Zijlstra, G. A. R. , Bours, G. J. J. W. , Hamers, J. P. H. , & Kempen, G. I. J. M. (2016). Development and usability of the MAINtAIN, an inventory assessing nursing staff behavior to optimize and maintain functional activity among nursing home residents: A mixed‐methods approach. BMC Health Services Research, 16, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuk, N. O. , Zijlstra, G. A. R. , Bours, G. J. J. W. , Hamers, J. P. H. , Tan, F. E. S. , & Kempen, G. I. J. M. (2017). Promoting functional activity among nursing home residents: A cross‐sectional study on barriers experienced by nursing staff. Journal of Aging and Health, 30(4), 605–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahmann, N. A. , Tannen, A. , Kuntz, S. , Raeder, K. , Schmitz, G. , Dassen, T. , & Kottner, J. (2015). Mobility is the key! Trends and associations of common care problems in German long‐term care facilities from 2008 to 2012. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52, 167–174. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J. N. , Fiatarone, M. , Kiely, D. K. , Belleville‐Taylor, P. , Murphy, K. , Littlehale, S. , … Doyle, N. (1999). Nursing rehabilitation and exercise strategies in the nursing home. The Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 54, M494–M500. 10.1093/gerona/54.10.M494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J. N. , Fries, B. E. , Mehr, D. R. , Hawes, C. , Philips, C. , Mor, V. , & Lipsitz, L. A. (1994). MDS cognitive performance scale. Journal of Gerontology, 49, M174–M182. 10.1093/geronj/49.4.M174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power, T. J. , Blom‐Hoffman, J. , Clarke, A. T. , Riley‐Tillman, T. C. , Kelleher, C. , & Manz, P. H. (2005). Reconceptualizing intervention integrity: A partnership‐based framework for linking research with practice. Psychology in the Schools, 42, 495–507. 10.1002/(ISSN)1520-6807 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raad voor Volksgezondheid en Samenleving (2017). Zonder context geen bewijs. Over de illusie van evidence‐based practice in de zorg.

- Resnick, B. , Galik, E. , & Boltz, M. (2013). Function focused care approaches: Literature review of progress and future possibilities. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 14, 313–318. 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick, B. , Galik, E. , Gruber‐Baldini, A. , & Zimmerman, S. (2011). Testing the effect of function‐focused care in assisted living. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59, 2233–2240. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03699.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick, B. , Gruber‐Baldini, A. L. , Zimmerman, S. , Galik, E. , Pretzer‐Aboff, I. , Russ, K. , & Hebel, J. R. (2009). Nursing home resident outcomes from the Res‐Care intervention. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57, 1156–1165. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02327.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick, B. , Petzer‐Aboff, I. , Galik, E. , Russ, K. , Cayo, J. , & Simpson, M. (2008). Barriers and benefits to implementing a restorative care intervention in nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 9, 102–108. 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick, B. , Simpson, M. , Bercovitz, A. , Galik, E. , Gruber‐Baldini, A. , Zimmerman, S. , & Magaziner, J. (2006). Pilot testing of the Restorative Care Intervention: Impact on residents. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 32, 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, R. P. , Evans, M. H. , & Joshi, P. (2005). Developing a process‐evaluation plan for assessing health promotion program implementation: A how‐to guide. Health Promotion Practice, 6, 134–147. 10.1177/1524839904273387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüssler, S. , Dassen, T. , & Lohrmann, C. (2014). Care dependency and nursing care problems in nursing home residents with and without dementia: A cross‐sectional study. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 28, 973–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuinman, A. , de Greef, M. H. , Krijnen, W. P. , Nieweg, R. M. , & Roodbol, P. F. (2016). Examining time use of Dutch nursing staff in long‐term institutional Care: A time–motion study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17, 148–154. 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Alphen, H. J. , Volkers, K. M. , Blankevoort, C. G. , Scherder, E. J. , Hortobagyi, T. , & van Heuvelen, M. J. (2016). Older adults with dementia are sedentary for most of the day. PLoS ONE, 11, e0152457 10.1371/journal.pone.0152457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkaik, R. , Francke, A. L. , van Meijel, B. , Spreeuwenberg, P. M. M. , Ribbe, M. W. , & Bensing, J. M. (2011). The introduction of a nursing guideline on depression at psychogeriatric nursing home wards: Effects on Certified Nurse Assistants. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48, 710–719. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkers, K. M. , & Scherder, E. J. (2011). Impoverished environment, cognition, aging and dementia. Reviews in the Neurosciences, 22, 259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, R. , Goodwin, V. A. , Abbott, R. A. , Hall, A. , & Tarrant, M. (2017). Exploring residents’ experiences of mealtimes in care homes: A qualitative interview study. BMC Geriatrics, 17, 141 10.1186/s12877-017-0540-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weening‐Dijksterhuis, E. , de Greef, M. H. , Scherder, E. J. , Slaets, J. P. , & van der Schans, C. P. (2011). Frail institutionalized older persons: A comprehensive review on physical exercise, physical fitness, activities of daily living, and quality‐of‐life. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 90, 156–168. 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181f703ef [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]