Abstract

Aims and objectives

To explore what meaning patients associate with their experiences with a nurse practitioner (NP) in oncological or palliative care.

Background

Care provided by NPs results in high patient satisfaction, mostly related to the assurance of continuity of care, and to receiving information and advice on coping with the disease. Research shows that health care provided by NPs equals the quality of care provided by physicians. Patients may be even more satisfied with care provided by NPs. Because patients’ views have only been examined quantitatively, underlying experiences and meanings remain unclear.

Design

A qualitative study from a phenomenological perspective.

Methods

In 2017, seventeen outpatients aged 45–79 years, receiving oncological or palliative care, were interviewed in depth. Data were analysed by Colaizzi's seven‐step method and by the Metaphor Identification Procedure.

Results

Six fundamental themes emerged: the NP as a human (1) and as a professional (2), the NP providing care (3) and cure (4), NPs organising patient care (5) and the impact on patient's well‐being (6). MIP analysis revealed six metaphors: NP means trust; is a travel aid; is a combat unit; is a chain; is a signpost; and is a technician.

Conclusions

NPs mean a lot to patients. NPs are valued as reliable, helpful and empathic. Patients feel empowered, at peace and in control as a result of the support, guidance and attention to them as a person as well as to aspects of the disease. Providing expert, integrated care makes patients feel safe and embraced in the NP's expertise.

Relevance to clinical practice

This qualitative insight into patients’ experiences will contribute to the body of knowledge on patients’ perceptions of the treatment and support provided by NPs. It adds to the further development of the NPs’ profession and education.

Keywords: hospital, metaphors, nurse practitioner, nursing, oncological and palliative care, patients’ experiences, patients’ meaning, phenomenological perspective

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

Details that empathy, helpfulness, reliability and personal attention to one's disease and quality of life by the NP are highly valued by patients receiving oncological or palliative care.

Emphasises that backup from the NP means a lot. NPs in oncological and palliative care make patients feel empowered, at peace and in control of the disease and its consequences.

Provides qualitative insight into how patients’ experiences contribute to the body of knowledge on patients’ perceptions of the treatment and support provided by NPs, and adds value to the further development of the NPs’ profession and education.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background

The nurse practitioner (NP) acts at the intersection of care and cure. The NP's tasks and responsibilities stem from the seven core competencies described in the Canadian Medical Education Directions for Specialists (CanMEDS framework): medical expert (the integrating role), communicator, collaborator, leader, health advocate, scholar and professional (Frank, Snell, & Sherbino, 2015; Ter Maten‐Speksnijder, Grypdonck, Pool, Meurs, & van Staa, 2014). In daily practice, NPs fulfil a broad range of roles depending on the work setting, the clinical discipline in which they function, the collaboration with the medical specialists, and the organisational policy regarding task allocation and professional development (Ter Maten‐Speksnijder et al., 2014).

Research shows that patients overall appreciate the care provided by an NP. In some studies, patients are even slightly more satisfied with the care provided by NPs than that provided by physicians (Broers et al., 2006; Festen, Duggan, & Coates, 2008; Laurant et al., 2008; Ter Maten‐Speksnijder et al., 2014; Van Hezewijk et al., 2011). Other studies, which involved not only NPs but also other levels of nurses, do not fully confirm these findings; in these studies, patient satisfaction varied with the context of care (Laurant et al., 2018 in press). From quantitatively oriented questionnaires like the “Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire III” (PSQ‐III) (Hagedoorn et al., 2003), it appears that patients are satisfied with NPs’ information provision on prognosis and recovery, the time available for consultation, their accessibility, communication skills, and information and support on coping with the disease in daily life (Broers et al., 2006; Laurant et al., 2008; Van Hezewijk et al., 2011). Also, patients perceive a high quality of life when treated by an NP (Broers et al., 2006; Festen et al., 2008; Laurant et al., 2008; Ter Maten‐Speksnijder et al., 2014; Van Hezewijk et al., 2011).

Yet, none of these studies gives a complete insight into the underlying experiences of patients and how concepts such as “satisfaction” and “quality of life” are understood. Hence, the question remains what patients really mean by these concepts. Just what is it that makes them feel satisfied? What is the impact of the extent of accessibility of the NP in daily life? What experiences make patients feel supported by an NP in coping with the illness? And especially, what value is associated with concepts such as availability, information and accessibility? To our knowledge, such ambiguous and emotionally charged concepts have not yet been explored in a qualitative, phenomenological way.

Producing an account of lived experiences in its own terms rather than by preexisting theoretical preconceptions could support further understanding of the NPs’ value to health care from the patient perspective.

2. METHOD

2.1. Aim

This study aimed to explore what meaning patients associate with their experiences with the treatment and support provided by an NP during oncological or palliative care.

2.2. Design

This study adhered to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007). A qualitative design from a phenomenological perspective was used because this perspective enables to explore interpretations and meanings of individuals’ experiences. As Polit and Beck put it: “The goal of phenomenological inquiry is to understand the lived experiences and the perceptions to which it gives rise” (Polit & Beck, 2012, p 495).

The meaning people associate with their experiences with the support of an NP is such a lived experience. To enable participants to recount their experiences as fully as possible, in‐depth interviews formed the main data source. Complementary sources were used to enhance understanding of the experiences as lived. Thus, the participants were also invited to explicate nonverbally what was in their “mind's eye” through symbolic representation using metaphors and pictures. Symbolism provides means of sharing one's experiences in a nonverbal way (Edward & Welch, 2011).

2.3. Sampling and selection procedure

To be able to explore the breadth of nursing and medical care in a population where quality of life is pivotal, a purposive sample of patients being in either an oncological or palliative trajectory supervised by an NP was recruited from three hospitals in two urban areas in the central Netherlands: one university and two top clinical (teaching) hospitals.

We included Dutch‐speaking adults with an oncological illness who were expected to be able to reflect on their experiences. Candidate participants were invited by their NP (eight NPs in total) and received an information sheet containing details of the study. Those who expressed interest in participating were contacted by telephone by the researcher (LvD), who provided further information and answered the remaining questions. Participants signed an informed consent form before being interviewed.

2.4. Data collection

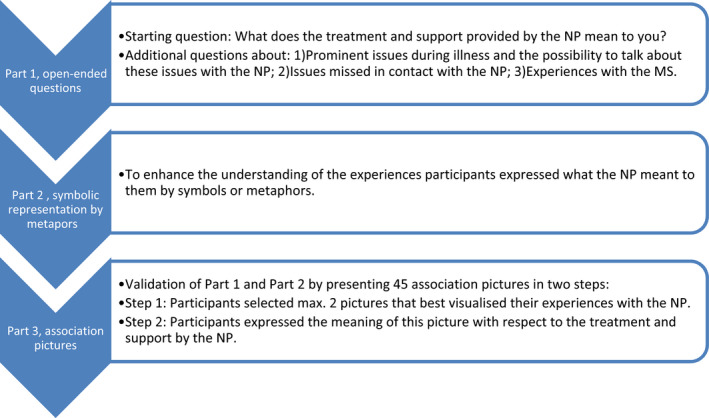

Data were collected by individual in‐depth interviews, conducted between June–October 2017. The interviews were guided by an interview guide developed by the authors. This guide was based on various sources: patients’ narratives in novels as well as in digital patient platforms, an exploratory talk with a patient, and the authors’ expert opinions. It was pilot‐tested on a 59‐year‐old male patient with metastasised kidney cell cancer. This did not lead to any changes. Each interview consisted of three parts: (a) open‐ended questions; (b) symbolic representations by metaphors; and (c) association pictures (see Figure 1). These parts are explained in detail below.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the three parts of the in‐depth interviews [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Part 1: Each interview started with the same open‐ended question: “What does the treatment and support provided by the NP mean to you?” To encourage participants to talk about their experiences and express what these meant to them, additional questions were asked, such as “What were prominent issues during your illness?” “What happened?” “Could you talk about these issues with your NP?” and “What was the impact of this conversation?” In addition, participants were asked whether they missed anything in their contact with the NP and were invited to briefly relate their general experiences with the medical specialist (MS).

Part 2: To enhance our understanding of the underlying experiences, participants were asked to express what the NP meant to them through metaphors (Edward & Welch, 2011). Principally, a metaphor is a symbolic comparison using figurative language to evoke a visual analogy, a way of conceiving of one thing in terms of another (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980/2003; Polit & Beck, 2012). Its primary function is understanding abstract, emotional or other experiences (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980/2003). Three types of metaphors are distinguished: (a) structural, (b) orientation and (c) ontological (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980/2003; Toren & Olivé, 2011). A structural metaphor is defined as a conceptual domain in terms of another conceptual domain (Beck, 2016; Kövecses, 2010). These two domains are named source domain and target domain. The source domain is the conceptual domain from which metaphorical expressions are drawn that help understand the target domain. For example, travelling, war, buildings and tools are source domains (B), whereas life, discussion and love are examples of target domains (A). A is understood in terms of B; for example, life is understood as travelling. Orientation metaphors are based on cultural and physical experiences. For example, “high is good,” so therefore “being happy and prosperity is upwards.” In ontological metaphors, also referred to as “personification,” nonhuman things are seen as human things (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980/2003; Toren & Olivé, 2011).

Part 3: The findings of the first and second parts were further validated by means of presenting a set of 45 “association pictures.” The interviewees were asked to select a maximum of two pictures that best visualised their experiences with the NP and to verbally express the meaning of the pictures with respect to the treatment and support by the NP.

The interviews were held at the participants’ homes and lasted approximately 60 min. All interviews were audio‐recorded.

2.5. Research team

The research team consisted of a researcher (LvD), a senior researcher (MG) and a research steering board. The steering board consisted of a Program Director Master Advanced Nursing Practice (JP), a professor of Pain and Palliative Medicine (KV), a professor of Innovation in Care (MA) and an associate professor of Skill Mix Change (AvV).

The interviews were conducted by LvD, who is a nurse and a nurse scientist. MG is a nurse, too, and a senior researcher and assistant professor at the Radboudumc Expertise Center for Pain and Palliative Medicine, a lecturer qualitative research at the Master Program Advanced Nursing Practice of HAN University of Applied Science, and Program Director Master Advanced Nursing Practice of Saxion University of Applied Science. Both are employed by the Radboud University Medical Centre. The researcher and the senior researcher are female and experienced in research and in interviewing vulnerable people.

The researcher had no relationship with the participants prior to the study commencement. At the time of the interview, participants were informed about the background and occupation of the researcher.

2.6. Ethical considerations

The study was assessed by the Medical Research Ethics Committee, which concluded that it did not fall within the remit of the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO). Review based on the Dutch Code of conduct for health research, the Dutch Code of conduct for responsible use, the Dutch Personal Data Protection and the Medical Treatment Agreement Act was judged positive (file number 2017‐3343). The study protocol was, in addition, approved by the local ethics committees of the two other participating hospitals. To protect the participants’ identities, ID numbers were used throughout the transcriptions. Participation was voluntarily; participants could withdraw from the study at any time and without giving any reason.

2.7. Data analysis

This study employs a phenomenological and interpretive research paradigm.

Data were analysed using Colaizzi's seven‐step method (Holloway & Wheeler, 2002; Polit & Beck, 2012), including an additional step (Edward & Welch, 2011) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Colaizzi's seven‐step method with inclusion of an additional step (Edward & Welch, 2011; Holloway & Wheeler, 2002; Polit & Beck, 2012)

| Colaizzi's seven‐step method of phenomenological enquiry with the inclusion of an additional step |

|---|

| 1. Transcribing all the subjects’ descriptions |

| 2. Extracting significant statements, that is, statements that directly relate to the phenomenon under investigation |

| 3. Formulating meanings for each significant statement |

| 4. Organising formulated meanings into clusters or themes |

| 5. Integrating results into exhaustive description of the phenomenon |

| 6. Additional step—interpretative analysis of symbolic representations |

| 7. Identifying the fundamental structure of the phenomenon |

| 8. Returning to the participants for validation of the findings |

In addition, the metaphors (step 6) were analysed using the Metaphor Identification Procedure (MIP), which consists of four steps (Edward & Welch, 2011; Pragglejazz Group, 2007) (Table 2). Computer software Atlas.ti version 7.1.5 was used to manage the data.

Table 2.

Four steps of the Metaphor Identification Procedure (MIP) (Pragglejaz Group, 2007)

| Four steps of the Metaphor Identification Procedure (MIP) |

|---|

| 1. Read the entire text–discourse to establish a general understanding of the meaning |

| 2. Determine the lexical units in the text–discourse |

| 3. (a) For each lexical unit in the text, establish its meaning in the context, that is, how it applies to an entity, relation or attribute in the situation evoked by the text (contextual meaning.(b) For each lexical unit, determine whether it has a more basic contemporary meaning in other contexts than the one in the given context. For our purposes, basic meanings tend to be more concrete (what they evoke is easier to imagine, see, hear, smell and taste); related to bodily action; more precise (as opposed to vague); and historically older.(c) If the lexical unit has a more basic current‐contemporary meaning in other contexts that the given context, decide whether the contextual meaning contrasts with the basic meaning but can be understood in comparison with it. |

| 4. If yes, mark the lexical unit as metaphorical |

2.8. Rigour

To assure trustworthiness of the data analysis, the researcher (LvD) used the following procedures: anonymous transcription of each interview; thick description; bracketing; making field notes after each interview; peer review and debriefing with the senior researcher (MG); and a member check (Holloway & Wheeler, 2002; Polit & Beck, 2012).

During the data collection period, LvD and MG started with the data analysis. LvD applied steps 2 and 3 of Colaizzi's method to all data. MG performed steps 2 and 3 for three interviews and checked the analysis of four randomly chosen other interviews performed by LvD. Simultaneously with steps 2 and 3, metaphorical expressions were coded as “metaphor” by LvD and MG separately, after which they compared and discussed the statements and determined the meanings. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Next, steps 4, 5 and 7 of Colaizzi's method were performed through collaboration between LvD and MG. The MIP (step 6) was initially performed by LvD. Through discussion with MG, consensus was reached about the final metaphors. The most selected pictures were identified by counts.

Data saturation was reached after having analysed 14 fully transcribed interviews. To confirm the preliminary findings or find deviating data, three more interviews were held. No deviating data or additional findings were found.

The identified themes, the fundamental themes and the metaphors were also discussed with the research steering board (JP, KV, MA, AvV) until consensus was reached. Finally, a member check took place (step 8): The participants were invited to respond to the findings by completing a questionnaire. The findings were presented to them in a general overview table containing quotes, emerged meanings, themes and fundamental themes.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of the participants

Seventeen persons were interviewed. Their mean age was 63.9 years (range 45–79), and nine of them (53%) were female. Colorectal cancer (n = 7) and breast cancer (n = 4) were the most common diagnoses. Five participants received palliative care. The onset of the disease varied from 1–5 years ago. See Table 3.

Table 3.

Participant characteristics

| ID | Gender | Age | Marital status | Diagnosis | Onset of disease | Nurse practitioner |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 59 | Married + children | Metastasised kidney cell cancer | Since 2014 | Internal oncological care |

| 2 | Female | 45 | Married + children | Breast cancer | Since 2013 | Surgical oncological care |

| 3 | Male | 72 | Married + children | Colorectal cancer | Since 2013 | Surgical oncological care |

| 4 | Female | 71 | Singlea | Colorectal cancer | Since 2012 | Surgical oncological care |

| 5 | Female | 67 | Single + children | Breast cancer | 2002 and since 2015 | Oncological care |

| 6 | Male | 65 | Single | Prostate cancer | Since 2016 | Palliative care |

| 7 | Female | 50 | Married + children | Metastasised breast cancer | Since 2014 | Palliative care |

| 8 | Male | 59 | Married + children | Metastasised kidney cancer | Since 2013 | Internal oncological care |

| 9 | Male | 56 | Single + children | Colorectal cancer | Since 2016 | Internal oncological care |

| 10 | Male | 60 | Married + children | Colorectal cancer | Since 2016 | Internal oncological care |

| 11 | Male | 71 | Married + children | Kahler's disease | Since 2016 | Palliative care |

| 12 | Female | 74 | Single + children | Metastasised breast cancer | 1989, 2008 and since 2013 | Palliative care |

| 13 | Female | 68 | Single | Colorectal cancer | Since 2014 | Internal oncological care |

| 14 | Female | 79 | Married + children | Colorectal cancer | Since 2016 | Surgical oncological care |

| 15 | Male | 79 | Married + children | Myelodysplastic syndrome | Since 2017 | Palliative care within surgical oncological care |

| 16 | Female | 63 | Married + children | Breast cancer | Since 2012 | Surgical oncological care |

| 17 | Female | 49 | Single + children | Colorectal cancer | 2011 and since 2013 | Surgical oncological care |

This marital status differs from never been married, divorced or being widow. Some of the single participants were, at the time of the interview, living apart or together with a new partner.

Depending on the intensity and phase of the treatment, the frequency of contact between the NP and the patient differed between once every 2–3 weeks (during chemo) and once every 6 months (during follow‐up). Mostly the contact was on a regular basis, which could be deviated from. All patients were supported by the same NP during the whole treatment course. The moment of first contact between the patient and the NP differed: In some cases, it was immediately after diagnosis or surgery even before chemotherapy; in other cases, it was later. Therefore, the duration of contact varied from 1–5 years, with the exception of one patient who had been in contact with the NP for more than 15 years since the cancer was first diagnosed in 2002. See Table 3.

3.2. Fundamental themes

Analysis of the interviews revealed six fundamental themes, composed of 18 theme clusters. The fundamental themes encompass the following:

The NP as a human.

The NP as a professional.

The NP providing care.

The NP providing cure.

The NP organising patient care.

Impact of the NP on the patient's well‐being.

See Table 4 for a thematic map on these themes and theme clusters.

Table 4.

Thematic map of emerged fundamental themes and theme clusters

| Fundamental themes | Theme clusters | Examples of formulated meanings |

|---|---|---|

| The NP as a human |

|

|

| The NP as a professional |

|

|

| The NP providing care |

|

|

| The NP providing cure |

|

|

| The NP organising patient care |

|

|

| Impact of the NP on patient's well‐being |

|

|

-

1

The NP as a human

For this fundamental theme, three theme clusters were identified: (a) the NP as an empathic, (b) helpful and (c) reliable person.

As for being empathic, the fact that the NP makes you feel welcome and is happy to talk with you meant a great deal to the respondents:

That's what I said, I don't worry about anything. Really not. I'm serious. And I only suffered from those side effects. But there I meet an open person who will be happy to talk to you. And wants to talk about it. So, you feel welcome. (ID10)

Providing special attention is also highly valued and considered important. This is apparent in the time available for consultation, personal attention and spontaneously visiting patients undergoing chemotherapy:

What I experienced and felt very clearly about her [the NP] is the personal attention and besides the whole medical story, much more like: “How about you? How are you doing in the process? How do you experience the process? What do you need for that?” That she paid a lot of attention to this in particular. (ID02)

When participants reflected on their experiences with the MS, opposite views emerged. Some participants positively valued the MS because of his/her involvement, kindness and attentiveness:

… But the fact that, in the evening after such a meeting, he [surgeon] really calls…. Well, I think that's quite something. Yes, so that deserves the highest appreciation. And that is why I commend him. (ID04)

Less valued were issues such as the lack of personal attention, the MS treating the participant as a case of illness, and poor communication skills. As one participant put it: “A doctor is very businesslike, isn't it? He only sees it as a disease case. Yes, we can do this and that, so and so.” (ID05)

Participants also told how their NP shows willingness to help, feels familiar and expresses confidence and reliability:

As you go through it, you have someone in the hospital who you can trust and who is helpful. And not only in an emotional sense, but also in a purely practical sense. That alone gives you a feeling of trust. You know, she herself radiates that already, that she is transferring it. You get the feeling of trust that you are in good hands. That you are well supervised. (ID09)

Several participants “clicked” right away with the NP but found it hard to define this sensation. Expressions like “I experienced a personal click, and that is of added value to me” (ID13), “We trust each other because of the good interaction” (ID10) and “The contact with my NP feels good” (ID03) illustrate the meaning of this experience.

-

2

The NP as a professional

Within this fundamental theme, four theme clusters were identified: (a) coach; (b) expert; (c) supporter; and (d) patients’ advocate.

For all participants, the NP represented a coach, who serves as a sounding board, coaches and advises. “His role, for that's what I find easiest, he coaches. The coach is…. The coach does nothing himself. He is standing along the sidelines and says how you should do it. For the rest, he himself does nothing. Still, he does make you better, in your own process.” (ID11)

The NP's (medical) expertise is also highly valued and appreciated. Likewise, the participants positively valued the MS because of his/her knowledge. Because the NP has experience, insight and understanding and has seen many comparable situations, the NP is seen as an expert and an authority:

She does have all the knowledge of all variants, all the treatments, all the possibilities, solutions, complications, and what else have you got. She is fully informed about this. This is what she has as a background, which makes her an expert partner to talk with. She knows how you are doing in that treatment and what is needed. (ID02)

Next to being a coach and expert, the NP represents a supporter who pays attention to the complete picture and offers physical and mental support. Apart from this, the NP is seen as a professional and is appreciated for being the patient's advocate. It means a lot to patients that the NP provides backup, keeps a finger on the pulse, acts as an intermediary, respects patients’ choices regarding quality of life, and knows, respects and anticipates to someone's struggles and doubts:

And as I just said, didn't I? She just knows me. She knows where my hurdles are, where my struggle is. And she understands that and she can steer it a little bit. (ID07)

In cases in which the NP acts as the patient's advocate, the NP's role is that of an intermediary, for example, as the gatekeeper to the chemotherapy.

Despite the above‐mentioned positive impressions, one participant (ID01) said he did not share his emotions or grief with his NP. He kept these problems private, but at the same time, the NP did not raise this matter. Another participant (ID07) did not talk about her short life expectancy with the NP, just because she did not find it necessary at the time.

-

3

The NP providing care

Underlying themes within this third fundamental theme are as follows: (a) discussing the treatment; and (b) advising the patient.

Discussing the treatment encompasses situations in which, among other things, the patient and the NP reflect on the previous period, and the NP consults on medication and side effects. As one participant said: “I am also technically involved with the NP about my illness. And what he zooms in on a bit more, is the situation around side effects. And…. when I say, “Oh dear, I hurt very badly in my side and I hurt in my back. As it started then. ‘Where exactly is that then? And can I take a look? May I just examine you a little bit? And do you also feel this? And do you have that too?’ Those kinds of things I mean.” (ID08)

Participants also appreciate that the NP takes the initiative to discuss topics such as the impact of the cancer on the relationship with the partner and on sexuality. Participants positively rate the serious attention given to the partner also:

Yes, our relationship. Also, how does it go at the given moment? Also, precisely because it hurts, precisely because you get older, how does it work with your sexual functioning, it all has an influence. …. That in turn brings tension, and that's something you can do without. He speaks quite openly about this, at least to us. (ID11)

The interviews reveal that the NP is valued for explaining things, answering questions about medication, supporting, giving guidance and reassuring the patient about the test results:

You can ask her whatever you like. As far as possible, she answers immediately, or you get an answer. She has the opportunity to access the MS instantly, I do not have that. I have to make an appointment. So, if there is a question, my wife always goes along, and then she contacts the MS immediately and we are called back instantly. (ID15)

-

4

The NP providing cure

Two theme clusters can be found within this fundamental theme: (a) monitoring; and (b) discussing test results.

The NP's role in providing cure is described as checking and monitoring one's (abnormal) blood values, and carrying out physical checks:

She always does check, too, yes. Just check it…. Yes, all lymph … After all, I recently also had a bump like that here … It is still a bit red…. Then she also says: “Probably already for some time.” And it… There was a bump. (ID05)

Next to monitoring, the NP explains the test results of ultrasound or scan and their consequences and discusses medication, side effects and (if necessary) changes in medication prescription (independently from or after consulting the MS):

After that, I was operated on again because the stoma had to be put back and then I had a conversation with her every once in a while. Also in connection with the results of the examination of blood, and of the ultrasound…. I think I had an MRI scan once afterwards. As a result of that she called me and then I went to talk with her. (ID04)

Exploring the experiences with the MS in the light of cure, participants stated: The MS is for medication, helps to cure the disease, gives information about the chemotherapy, is medical/technically focused and operates according to the clinical protocol. As ID02 literally said:

The contacts with the surgeon were good, but that is more technical and focused on the medical side of the story.

-

5

The NP organising patient care

Within this fundamental theme, two theme clusters were identified: (a) coordination; and (b) collaboration with other professional caregivers.

Coordination consists of the NP being easy accessible, the NP coordinating the activities of the professionals involved and the NP being the first point of contact in the hospital to address questions or problems. Participants are glad that the NP performs this role:

He [the NP] was my mouthpiece for the hospital. As it were, my gatekeeper to the doctor. And that works fantastic. That works very well. He was very attentive. Also answers back immediately to things. Easily accessible. (ID08)

All the more they missed accessibility to and continuity by the MS: “…. the oncologist is likely to be someone else. Because they are busy or have a new schedule, I wouldn't know why. Then I get someone else. Or—well—my own oncologist has just moved away. So is no longer there, then I get a new one. Well then, it always takes some time to get used to it. For the NP is always there. That continuity is very pleasant” (ID07). Furthermore, all respondents highly value that the NP responds to questions immediately or—if the MS should be consulted—as soon as possible by phone or email.

Participants described several situations in which the NP takes the initiative for collaborating with and contacting the MS or other professionals in case of medical, physical, mental, social or practical problems:

Well, yes … that I did indeed say like: “Oh boy, maybe it's a good idea that we should talk to… medical… psychologist or social services.” I mean, then it was just going very bad…. In no time an appointment has been arranged and I can have a talk with that department. (ID01)

Concerning this theme, individual interviewees mentioned several missed opportunities. They had missed, for example, contact with the NP on a regular basis, contact immediately after surgery, the NP's presence when the MS explained scan results, and referral to medical devices or support in the mourning process.

Concerning the collaboration between the NP and the MS, some participants valued the NP and MS equally at the medical domain. One person noted blurred boundaries between the competences of both professionals but did not see that as a problem. Other findings were the NP reducing the executive tasks of the MS, the NP as intermediary to the MS and the NP consulting the MS for complex medical problems. A few participants felt that they partnered with the NP and MS as a threesome, which they highly appreciated. As shown in the following quote: “Because if we then come to some sort of conclusion, how do we deal with those pains, that all three have heard the same thing…. And if there is a need to intervene on this, if I think so or if he thinks so, that the MS also knows from which side the request comes. And then it works. Then the triumvirate works optimally.” (ID08)

Furthermore, the NP's role was seen as complementary to the treatment by the MS. Because of the integration of the medical and nursing domains by the NP, participants experienced the contact with the NP as a focus on a different, for example, less medical, perspective.

-

6

Impact of the NP on patient's well‐being

The analysis of the interview data showed a significant impact of the NP's involvement on patients’ well‐being. Within this fundamental theme, four theme clusters were identified: (a) empowerment; (b) peace and calmness; (c) being in control of one's disease as well as the consequences; and (d) personal attention.

All interviews revealed that the guidance, treatment and support of the NP was of great help and made the participants feel more empowered, that is, becoming stronger and more confident, especially in controlling one's life. The NP enables them to cope with the disease and the impact of the disease in daily life and helps them to set goals to regain one's own life:

That you choose for more quality of life after all. And that's always the balance between…. Well, if I take more pills I can do things longer. I am more active during the day…. And that is also very important. And for me, I have a choice. For example, I can also say: “I'm going to lie down a little longer in the afternoon.”… Sometimes it's just a great nuisance to do that. And then she [the NP] says: “If you have a nice day out or something like that, just take an extra pill. That is not a problem. Allow this yourself, that's actually more. Granting… Allowing yourself that kind of thing makes life a bit more fun. And in that sense, caring for yourself is important. And this is something I learn from talking with her. (ID07)

For patients with cancer, the experience of a life‐threatening illness can cause distress. For them, contact with the NP means peace and calmness. By providing continuity, the NP takes away fear, provides rest and conveys confidence in the treatment. Patients feel protected and taken care of:

She always reassures me, because through everything that has happened I have lost all trust [in my body and in caregiving]. Even when she notices that it bothers me a lot, the lines are very short. Then she just talks a little while with the MS, then she fine‐tunes things with him. For example, I felt a hump at my groin and started to worry ‘could this again be something?’ …. She understands that I worry a lot and then checks whether the MS has got time to look at it. The MS came to check a little later and then my worries were gone right away. (ID17)

As you go through it, you have someone in the hospital who you can trust and who is helpful. And not only in an emotional sense, but also in a purely practical sense….. You get the feeling of trust that anyway you are in good hands. That you are well supervised and that… gives peace. Ultimately actually peace and overview. (ID09)

Contact with the NP makes the interviewees feel in control of the disease and, for instance, its consequences for daily life activities. The NP provides clarity about pain management, and blood values/test results. The NP can be asked everything and is willing to discuss concerns about their private situation. This helps in coping with the disease:

She [the NP] always ensures that these subjects are addressed so that she has the whole picture of me. So, then it is indeed like:”How is it going at home? How do you sit together? Are you back at work? She is the one in the hospital where you can go. Where you indeed with questions about treatment and what is the situation and is it really true that I don't need chemo? That is something you discuss with your surgeon, but the other side is covered by her. (ID02)

Regarding personal attention, the NP pays attention to quality of life and personal background. Patients feel understood and seen as being more than “just a number” by the NP who could read them like a book: “I am seen as a human being and not treated as a senior patient.” (ID15)

But it is true that those ten minutes that you're there….Then it really is your fight. And then it is he [the NP] who helps you. And then it will become very personal….Then you feel that it is for you and that you are working on it together. And that gives a good feeling. That in this case you come as P with his wife. And not as number 365. (ID08)

“I wanted to see if I would feel better without those tablets, those hormone tablets…. And we were able to talk about that very well. And she [the NP] says: “If you … quality of life… maybe you're going to be all right too. It is not needed at all.” She did indicate that. And that made me decide: “Yes, let's just try it.” (ID05).

3.3. Metaphors

The MIP analysis showed that participants eventually used two types of metaphors: structural and ontological metaphors. Within these two types, six different metaphors emerged, representing symbolic descriptions of the experiences and attached meanings. Each of these metaphors is described below per main type.

3.3.1. Type 1: structural metaphor

The NP means trust

Different participants mentioned how the relationship with the NP is based on trust. They have confidence in the NP's expertise; the NP feels like a warm nest to them; NP is a sympathetic ear, shows involvement and takes account of the complete picture; and one feels being kept on a leash by the NP.

One person who mentioned this type of metaphor described it this way: “Of course, that comes first and foremost. The cancer. But she also has an eye for everything around it.” (ID05)

Another participant said: “So what I have experienced so far is conversations. First by telephone and then there. And then she [the NP] always called me after I had been in contact with the doctor or after something had happened…. So, I feel like I'm on a line and not swimming freely anymore.” (ID12)

3.3.2. Type 2: ontological metaphors

-

1

The NP is a travel aid

Most frequently used in this ontological metaphor was the description depersonalising the NP into a beacon. The NP is always accessible in times of need, in case of (medical) problems or for answering urgent questions. When one feels upset or shattered, the trust in the NP's expertise is valued as comforting.

One participant expressed this as follows: “You do need people. Among others the NP. Certainly, from a medical point of view. If there was something medical… She also always said: ‘[first name P], don't doubt, if you think there is something wrong at home, call me. I prefer that you call even if nothing's the matter.’… And that is, of course, very important. And even if she said, ‘Take this and this and this and then we will wait until tomorrow and then call you back…,’ you were reassured. So, I think it was also a question of trust in the skill with which she approached me. And that is also very important, of course. Certainly, in such a situation that you are upset. Then you are alone at home and then you think: ‘Yes, I should really call oncology, because this is not acceptable.’ And then, of course, the NP is a beacon for you at that moment.” (ID13)

Other, less frequently used, metaphorical expressions were lifebuoy sign and tower of strength. One participant who came up with the latter metaphor described it this way: “I don't have…. no parents anymore. Yes, is logical somehow at this age. Siblings. Yes. Also friends and acquaintances I can talk to. But on the disease level or my body and everything, there she has…. There you talk with… I can talk about it well with her. How I feel. The family situation….. Or whatever else has been a lot of misery. Yes, those kinds of things…. If something was the matter…. Yes, a nice talk with the NP and you heard again that it was going well. Yes…. that I was always able to tell her my story.” (ID05)

-

2

The NP is a combat unit

For this ontological metaphor, some participants visualised their collaboration with the NP as a “fight against cancer.” The NP is like a partner in crime, someone with whom they fight to beat cancer:

“…….. join forces to fight against opponents who are in the same class as you. You go as a team, you enter there a bit stronger. It has something of an unfair struggle because the inequality is there. It is not an equal team that you're going to play a game against. Although you do this as a team together.” (ID08)

Another use of this type of metaphor in which the NP is like a captain was the expression: “This is also a battle which you fight with the enemy. NP is the captain. And I'm spinning out a little bit.” (ID04)

-

3

The NP is a link

Many participants described the experiences with the NP through the ontological metaphor of a chain. The NP is a vital link to connect the chain of their illness; the NP is a checkpoint, an intermediary and a mouthpiece. Here are a few examples of the use of this metaphor:

He is my admission to the immuno, a transit station. (ID01)

She is the one who sees you completely, who keeps an eye on the personal side of the treatment. I think she is the link between medical and human. (ID02)

So, I very quickly had contact with him by mail also, at his mobile number I got from him on his card So he was my mouthpiece for the hospital. As it were, my gatekeeper to the doctor. (ID08)

-

4

The NP is a signpost

This use of this ontological metaphor of guidance and support signified yet another aspect of the NP as experienced by participants. Some participants felt lost and caught by the disease. The NP helps to pick up the thread of daily life and steers them in the right direction to accomplish personal goals, as the following quote reveals: “I understand that I have to do it all myself, I have the insights to a large extent also on the basis of life experience and tripping up in life, so to speak…. He reminds me of it and he helps me…. So, when it comes to his activities, it's about his coaching, like ‘You do it right.’ Or ‘Do you know for sure?’ The applause every now and then, but also like: ‘Do you remember that we have agreed….?’ to do this or that.” (ID11)

I knew what was going to happen at a given moment and I also knew that, if I would get lost for a while, I could rely on her to show me the right direction again. (ID09)

-

5

The NP is a technician

In this personification metaphor, some participants gave the NP a technical quality by referring to a maintenance inspection. Issues like test results of scans or blood values, the recent treatment, experiences and problems were shared and discussed. In some cases, the NP gave permission to enter chemotherapy, based on the test results. This metaphorical expression is reflected by the following quotes:

It is an eh check and….. check the… things as they are there: blood results or whatever,… Currently he is there… does signify not so much. Yes, he is my admission to the immuno. (ID01)

Yes, see it as a kind of maintenance…. I also always liked going there. To hear the results. To obtain permission. And briefly talk about that period, about the recent period. How did you feel about that? What have you experienced? What was disappointing, what was better than expected? (ID10)

3.4. Symbolic representation by association pictures

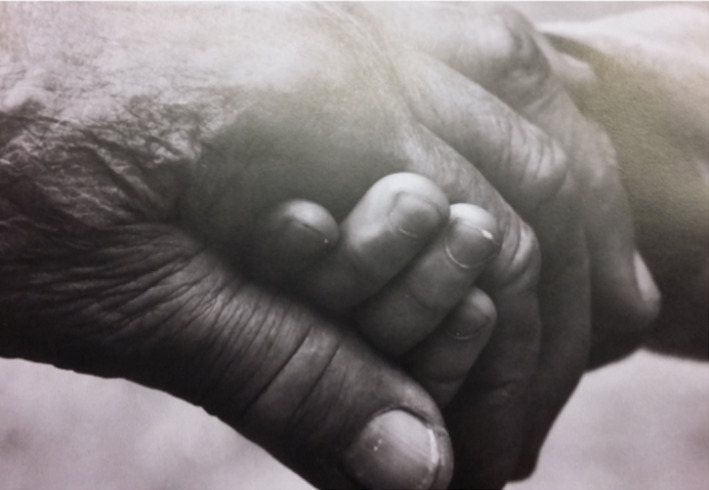

Of the 45 association pictures presented to the participants, the three most selected ones represented the contact with the NP: (a) two people holding hands, associated with “feeling safe, doing it together” (5x); (b) rafting in wild water, representing “fighting the battle together, with the NP in the lead” (3x); and (c) jigsaw puzzle, representing “the NP helps to complete the puzzle” (2x). See pictures 1, 2, 3, respectively. Seven other selected pictures were associated with “trust,” “feeling safe and protected,” “working together,” “attention and soothing effect” and the NP representing a “signpost.”

Picture 1.

Feeling safe, doing it together [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Picture 2.

Fighting the battle, with the NP in the lead [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Picture 3.

NP helps to complete the puzzle [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4. DISCUSSION

The findings of this explorative study about patients’ perceptions of the NP oncological or palliative care suggest that patients highly appreciate the NP for six fundamental issues: (a) the NP as a human, with empathy, helpfulness and reliability as central concepts; (b) the NP as a professional, with the key roles of coach, expert, supporter and patient's advocate; (c) the NP providing care, with discussing the treatment and advising revealed as central themes; (d) the NP providing cure, with monitoring and discussing test results as important themes; (e) the NP organising care, with coordination and collaboration with other professional caregivers considered important; and (f) the impact of the NP on patients’ well‐being, with participants feeling more empowered, in peace, calm and in control of the disease, and the personal attention which makes them feel understood and being more than “just a number.”

Our findings are in line with previous studies reporting that patients overall well appreciate the care of NPs (Broers et al., 2006; Festen et al., 2008; Laurant et al., 2008; Ter Maten‐Speksnijder et al., 2014; Van Hezewijk et al., 2011). Still, our findings additionally provide a unique qualitative insight into the underlying meaning patients receiving oncological and palliative care associate with their experiences with the NP. While the focus of quantitative studies lies on more technical and abstract concepts such as accessibility/direct communication, time available for consultation, continuity, or information regarding prognosis and recovery, participants in our study emphasise the interpersonal aspects of the NP's care and the impact of these aspects on their well‐being. We believe that these qualitative findings narratively substantiate the quantitative technical and abstract concepts.

The meanings identified in our study (see Table 4) suggest that in general, the NP acts on the intersection of cure and care, with attention to physical, social, psychosocial and existential needs. This seems to connect well to Dierckx de Casterlé's concept of “skilled companionship” (Dierckx de Casterlé, 2015). The author discerned three levels of nursing care. First‐level care reflects an instrumental relationship between a patient and a nurse. Second‐level care is characterised by actions and an attitude that clearly recognise the patient and his or her individual needs. The harmonious integration of a high level of competency and a caring attitude is the key characteristic of third‐level care, according to Dierckx de Casterlé (2015). It is driven by the concept of “skilled companionship,” which implies that a patient, when sick or being treated, feels accompanied and supported by the empathic presence of a nurse. Patients feel that nurses understand what they are going through and what this means for them. Although this level of care is implicitly strongly desired, patients rarely experience “skilled companionship” in practice. These findings seem in line with the existing literature on care needs, which indicates the existence of a diversity of individual met and unmet needs of people with cancer. In a study by Harrison, Young, Price, Butow, and Solomon (2009), the most frequently reported unmet needs were those in the domain of activities of daily living (not being able to do the things one used to do), followed by the psychological (fears, concerns and uncertainty), information, psychosocial and physical (pain, tiredness) domains. More specifically, a study among women with oestrogen‐positive metastatic breast cancer showed that lack of psychological support—for example, support to cope with the “rollercoaster switching between anxiety and relief”—was the greatest unmet need (Lee Mortensen, Bredbjerg Madsen, Krogsgaard, & Ejlertsen, 2017). In their systematic literature review of supportive care needs among women with gynaecological cancer and their caregivers, Beesley, Alemayehu, and Webb (2017) found that the total burden of needs was predominately related to help with fear of recurrence, worries of caregivers and fatigue, pain and associated costs, sexuality issues, genetic testing and disease‐specific peer support. The exploration of needs of cancer patients in palliative care by Melhem and Daneault (2007) revealed that next to medical expertise, patients need respect and validation of their experiences, need to be heard without judgement and need reassurance. These aspects also mirror the “presence approach” (Baart, 2002). This approach, originated from the Netherlands, is built around the items patience, unconditional attentiveness and receptivity. Practitioners who use the “presence approach” cross domains if the requests for help necessitate this (Baart, 2002). They walk part of the way with their patients and make room for their stories, and are deeply concerned with identity, coping and orientation questions. According to our participants, the NPs concerned seem to possess the competences and skills to realise “skilled companionship” and to smoothly collaborate with other professional caregivers. In all, this results in attention to the broad spectrum of care needs and to the patient's “complete picture,” which are pivotal aspects in oncological and palliative care.

4.1. Limitations

Some methodological limitations should be considered while interpreting the results. First, the sample consisted of patients receiving (although diverse) oncological and palliative care only and was heterogeneous in age, time elapsed since the onset of the disease, and level of education. This might hinder the transferability of the findings in this study.

Second, participants were recruited by their NPs, based on the inclusion criteria formulated in the study protocol. Still, they needed to assess whether a potential participant was able to reflect on personal experiences and had the psychological and social strength to take part in the study. This may have led to some selection bias, either in a positive direction (motivated patients with high appreciation for the NP having a greater likelihood of being selected) or in an unknown direction (patients with less ability to reflect might not have been selected, and it is unknown how they value their NPs’ care and support). Despite these potential limitations, we have faith in the trustworthiness of our study. The rigour of the data collection and data analysis and the applied steps and methodologies strengthen the value of the achieved insight.

Our findings represent the situation in the Netherlands, in which the NPs act at the intersection of cure and care, blending medical and nursing competencies (Ter Maten‐Speksnijder et al., 2014). Although NPs in the Netherlands have acquired expert knowledge at the internationally acknowledged level of advanced practice nursing (Chan & Cartwright, 2014), their tasks and role perhaps cannot be completely generalised to a wider international context.

To our belief, this is the first study exploring in depth what meaning patients associate with the treatment and support by an NP. Despite the above‐mentioned limitations, the qualitative findings importantly add to the body of knowledge on NPs’ roles and practices.

5. CONCLUSION

Backup from the NP means a lot to patients. The participants in this study—patients receiving oncological or palliative care—valued the NP as reliable, helpful and empathic. They felt empowered, at peace and in control thanks to the NP's support, guidance and personal attention to them as a person as well as to aspects of the disease. Realising that NPs provide integrated care at expert level made them feel safe and embraced in the NPs’ expertise.

6. RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

This newly gained insight into patients’ experiences is of added value to the further development of the NPs’ profession and education. It makes clear that NPs need to be aware of the broad spectrum of care needs and the patient's need for attention to the “complete picture.” Furthermore, the concepts “skilled companionship” and “presence approach” should be included in the curricula of the Master of Advanced Nursing Practice programmes and should be addressed in the (compulsory) peer‐to‐peer coaching after graduation. On the organisational level, our research findings can be helpful in selecting suitable candidates for NP vacancies.

Participants in this study experience(d) a life‐threatening illness, and therefore are a specific population. The emerged evidence will not be sufficiently conclusive to be generalised to care provided by NPs to other populations. Future research should therefore explore patients’ view on the care provided by NPs in other settings, for example, COPD care or mental health care. Also, it might be interesting to explore whether patients in other countries, or in quite different settings like acute care, give meaning to their experiences with NPs.

van Dusseldorp L, Groot M, Adriaansen M, van Vught A, Vissers K, Peters J. What does the nurse practitioner mean to you? A patient‐oriented qualitative study in oncological/palliative care. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:589–602. 10.1111/jocn.14653

Funding information

This research received a specific grant from the Department of Master Advanced Nursing Practice at HAN University of Applied Science, Nijmegen, the Netherlands—a nonprofit organisation.

REFERENCES

- Baart, A. J. (2002). The presence approach: An introductory sketch of a practice. Catholic Theological University Utrecht, 2002, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, C. T. (2016). Posttraumatic stress disorder after birth: A metaphor analysis. CE 2.0 ANCC Contact Hours, 41(2), 76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesley, V. L. , Alemayehu, C. , & Webb, P. M. (2017). A systematic literature review of the prevalence of and risk factors for supportive care needs among women with gynaecological cancer and their caregivers. Supportive Care in Cancer, 26, 701–710. 10.1007/s00520-017-3971-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broers, C. , Hogeling‐Koopman, J. , Burgersdijk, C. , Cornel, J. H. , van der Ploeg, J. , & Umans, V. A. (2006). Safety and efficacy of a nurse‐led clinic for post‐operative coronary artery bypass grafting patients. International Journal of Cardiology, 106, 111–115. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K. G. , & Cartwright, C. C. (2014). The clinical nurse specialist In Hamric A. B., Hanson C. M., Tracy M. F., & O'Grady E. T. (Eds.), Advanced practice nursing; an integrative approach, Part III advanced practice roles: The operational definitions of advanced practice nursing, 5th ed. (pp. 359–368). St. Louis, MI: Saunders Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Dierckx de Casterlé, B. (2015). Realising skilled companionship in nursing: A utopian deal or difficult challenge? Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24, 3327–3335. 10.1111/jocn.12920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edward, K. , & Welch, T. (2011). The extension of Colaizzi's method of phenomenological enquiry. Contemporary Nurse, 39(2), 163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festen, L. , Duggan, P. , & Coates, D. (2008). Improved quality of life in women treated for urinary incontinence by an authorized continence nurse practitioner. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction, 19(4), 567–571. 10.1007/s00192-007-0468-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, J. R. , Snell, L. , & Sherbino, J. , editors. (2015). CanMEDS 2015 physician competency framework. Ottawa, ON: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedoorn, M. , Uijl, S. G. , Van Sonderen, E. , Ranchor, A. V. , Grol, B. M. F. , Otter, R. , … Sanderman, R. (2003). Structure and reliability of ware's patient satisfaction questionnaire III: Patients’ satisfaction with oncological care in the Netherlands. Medical Care, 41(2), 254–263. 10.1097/01.MLR.0000044904.70286.B4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J. D. , Young, J. M. , Price, M. A. , Butow, P. N. , & Solomon, M. J. (2009). What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review Supportive Care in Cancer, 17, 1117–1128. 10.1007/s00520-009-0615-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, I. , & Wheeler, S. (2002). Qualitative research in nursing. Blackwell Science, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, O. (2010). Metaphor: A practical introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G. , & Johnson, M. (1980/2003). Metaphors we live by. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laurant, M. H. G. , Hermens, R. P. M. G. , Braspenning, J. C. C. , Akkermans, R. P. , Sibbald, B. , & Grol, R. P. T. M. (2008). An overview of patients’ preferences for, and satisfaction with, care provided by general practitioners and nurse practitioners. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17, 2690–2698. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02288.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurant, M. , van der Biezen, M. , Wijers, N. , Watananirun, K. , Kontopantelis, E. , & van Vught, A. J. A. H. (2018). Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Mortensen, G. , Bredbjerg Madsen, I. , Krogsgaard, R. , & Ejlertsen, B. (2017). Quality of life and care needs in women with estrogen positive metastatic breast cancer: A qualitative study. Acta Oncologica, 57, 146–151. 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1406141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melhem, D. , & Daneault, S. (2007). Needs of cancer patients in palliative care during medical visits. Canadian Family Physician, 63, e536–e542. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D. F. , & Beck, C. T. (2012). Phenomenological analysis In: Nursing research. Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (pp. 536, 565‐569). 9th ed Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer: Lippincott Williams and Wilcot. [Google Scholar]

- Pragglejaz Group (2007). MIP: A method for identifying metaphorically used words in discourse. Metaphor and Symbol, 22(1), 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Maten‐Speksnijder, A. , Grypdonck, M. , Pool, A. , Meurs, P. , & van Staa, A. L. (2014). A literature review of the Dutch debate on the nurse practitioner role: Efficiency vs. professional development. International Nursing Review, 61(1), 44–54. 10.1111/inr.12071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. , Sainsbury, P. , & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32 item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19, 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toren, S. , & Olivé, E. P. (2011). Something with Mars and Venus; research about the use of metaphors in the movie industry, from a gender perspective. Master thesis Communication Science, University of Groningen.

- Van Hezewijk, M. , Ranke, G. M. C. , van Nes, J. G. H. , Stiggelbout, A. M. , de Bock, G. H. , & van de Velde, C. J. H. (2011). Patients’ needs and preferences in routine follow‐up for early breast cancer; an evaluation of the changing role of the nurse practitioner. EJSO The Journal of Cancer Surgery, 37, 756–773. 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]