Graphical abstract

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019, SARS-CoV-2, Main protease, Virtual screening, Molecular dynamics simulations, Drug discovery

Highlights

-

•

The main protease (Mpro, 3CLpro) of SARS-CoV-2 is considered as a potential drug target for drug development.

-

•

Using advanced computational studies, we have identified two potent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

-

•

Both 6-Deaminosinefungin and UNII-O9H5KY11SV bind strongly to the residues active site pocket.

-

•

The complexes of both compounds with the main protease were stable throughout the MD simulation.

-

•

Both the molecules may be further exploited as preclinical leads for therapeutic management of COVID-19.

Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease, caused by a newly emerged highly pathogenic virus called novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Targeting the main protease (Mpro, 3CLpro) of SARS-CoV-2 is an appealing approach for drug development because this enzyme plays a significant role in the viral replication and transcription. The available crystal structures of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro determined in the presence of different ligands and inhibitor-like compounds provide a platform for the quick development of selective inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. In this study, we utilized the structural information of co-crystallized SARS-CoV-2 Mpro for the structure-guided drug discovery of high-affinity inhibitors from the PubChem database. The screened compounds were selected on the basis of their physicochemical properties, drug-likeliness, and strength of affinity to the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Finally, we have identified 6-Deaminosinefungin (PubChem ID: 10428963) and UNII-O9H5KY11SV (PubChem ID: 71481120) as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro which may be further exploited in drug development to address SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Both compounds are structural analogs of known antivirals, having considerable protease inhibitory potential with improved pharmacological properties. All-atom molecular dynamics simulations suggested SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in complex with these compounds is stable during the simulation period with minimal structural changes. This work provides enough evidence for further implementation of the identified compounds in the development of effective therapeutics of COVID-19.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) emerged from China and globally affected a larger population through human-to-human transmission (Guan et al., 2020). Due to the high reproduction rate of novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and unavailability of effective drugs and vaccines, the number of reported cases and death are increasing day by day (Huang et al., 2020). The disease is now pandemic across the globe claiming the death of more than 0.6 million lives worldwide (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/). SARS-CoV-2 belongs to Nidovirus superfamily of Coronavirus, which is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus, and the seventh coronavirus having the potential to infect humans (Chary et al., 2020; Naqvi et al., 2020). The genome of SARS-CoV-2 is 29.9 kb in size and shows a high similarity to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (Lu et al., 2015b).

The genome of SARS-CoV-2 is composed of 13–15 open reading frames (ORFs) flanked by the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) and 3′-UTR (Lu et al., 2020). All the ORFs are arranged as main replicase assembly encoding 27 structural and non-structural proteins (Liu et al., 2020; Minakshi et al., 2014). Two-third of its RNA situated in the first ORF (ORF1ab) that encodes a 7096 amino acids long polyprotein. The viral genome of SARS-CoV-2 translates into four major structural proteins viz. envelope (E), membrane (M), spike (S), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins. All these proteins play a vital role in the viral assembly (Zhang and Holmes, 2020).

The spike protein (S) is important for coronavirus transmission, as it mediates receptor binding and membrane fusion of the virus to the host angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a cell receptor for SARS-CoV-2 (Lu et al., 2015a; Wang et al., 2016). The S1 domain of S protein helps in receptor binding as it recognizes and binds to the host receptor through the receptor-binding domain (RBD), and the subsequent conformational transition of the S2 domain take place to facilitate the fusion of cell membrane (He et al., 2004; Wong et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2020). Transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2) plays a key role in the fusion of virus and host cell by priming S protein. The RBD binds to receptor ACE2 of the host which provides entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the respiratory tract (Zhou et al., 2020). The affinity with which S protein of SARS-CoV-2 binds to the ACE2 is more than 10 times than that of SARS-CoV. The increased affinity of human ACE2 for the viral protein facilitates its high contagious nature among the human population (Wrapp et al., 2020).

The uncontrolled situation, mass infection, and high death along with the lack of effective therapeutic measures are emergent issues related to COVID-19 globally. Several strategies have been employed to address COVID-19 by using existing broad-spectrum antivirals, including anti-HIV drugs such as ritonavir and lopinavir (Sheahan et al., 2020). Amongst the well-characterized drug targets of coronaviruses, main protease (Mpro, also called 3CLpro) is mostly considered as it is essential for processing the polyproteins that are translated from the viral RNA (Anand et al., 2003). Mpro cuts polyproteins translated from viral RNA to produce functional viral proteins. This enzyme is primarily involved in the regulation of replication and transcription of virions, thus targeted to design and develop effective therapeutic molecules for COVID-19.

Computational methods can serve as a great asset in the present times due to their ability to work at a rapid and helping manner to find potential inhibitors for drug targets of SARS-CoV-2 (Shamsi et al., 2020). Structure-based drug design and discovery approach is used to find effective molecules with high affinity and target specificity (Khan et al., 2019). The identification of new leads with high specificity is achieved by virtual high-throughput screening (vHTS) (Mohammad et al., 2020). This method identifies considerable drug-like candidates from a large chemical library based on the binding of ligands to target proteins with high affinity (Naqvi et al., 2018).

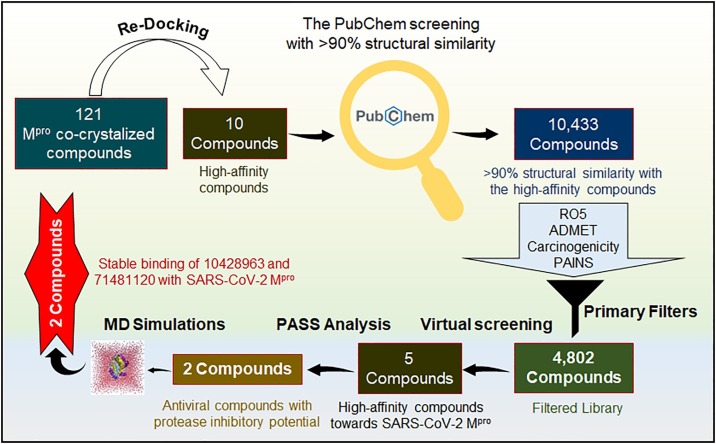

Prompt development of effective drugs for COVID-19 therapy is a difficult task as the conventional drug development process usually takes a long time and cost in billions. The optimization and reconsideration of available antiviral compounds offers an alternate approach to rapidly identify potential leads for the quick development of effective and safe drugs. In this study, we have extensively analyzed the available structures of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro co-crystallized with different compounds and employed to structure-guided rational drug design approach to find potential inhibitors with improved pharmacological properties (Dai et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). First, redocking of 121 reported compounds (co-crystallized with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro) was carried out to search high-affinity binding partners of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro which were served as scaffolds to screen the PubChem database with >90 % structural similarity. Then, we performed molecular docking-based virtual screening of the PubChem compounds and estimated their binding affinities with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Finally, after the interaction analysis and based on the biological properties, we have identified two compounds for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. A systematic approach based on structure-based drug designing was used in this study as described in Fig. 1 . We have identified two compounds, 6-Deaminosinefungin (PubChem ID: 10428963) and UNII-O9H5KY11SV (PubChem ID: 71481120) as high-affinity inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

Fig. 1.

The workflow demonstrates the process of virtual high-throughput screening used in this study. RO5, Lipinski's rule of five; ADMET, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Structure-based virtual screening

This study was performed on the DELL® Workstation running on Ubuntu version 18.04.4 LTS. Computational tools, such as MGL Tools (Jacob et al., 2012), AutoDock Vina (Trott and Olson, 2010), and Discovery Studio visualizer (Biovia, 2015) were used for structure-guided vHTS. A total of 158 SARS-CoV-2 Mpro structures were retrieved from the PDB. Most of them were in complex with different inhibitors. We found a total of 121 unique ligands co-crystallized with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and extensively analyzed to get insights into their mode of binding and inhibition to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. We re-docked these 121 ligands with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB ID: 6M03, Resolution: 2.0 Å) to estimate their binding affinity while using the molecular docking approach and selected top high-affinity binding partners (hits) of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

We further screened the PubChem database to get compounds with >90 % structural similarity (Tanimoto threshold) with the high-affinity hits of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. The identified compounds from the PubChem database were screened further based on their physicochemical properties following the Lipinski’s rule of five (RO5), and showing appreciable ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity), and other drug-like properties with no carcinogenic and PAINS patterns. To identify high-affinity inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, molecular docking-based virtual screening was performed. Before docking simulations, energy minimization was performed on the protein structure to remove possible steric clashes in finding its most stable and lowest energy conformation state. The protocol for docking has been described in our previous communication (Shamsi et al., 2020).

Values of inhibition constant (pKi), the negative decimal logarithm of inhibition constants were calculated from the ΔG, generated from the docking study using the following formula-

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where ΔG, binding affinity (kcal/mol); R (gas constant), 1.98 cal*(mol*K)−1; T (temperature), 298.15 K; pred, predicted.

Ligand efficiency (LE) is a commonly applied parameter for lead selection by comparing the values of average binding energy per atom (Hopkins et al., 2004). The following formula was applied to calculate LE:

| LE = -ΔG/N |

where LE is the ligand efficiency (kcal mol−1 non-H atom−1), ΔG represents binding affinity (kcal mol−1) and N is the number of non-hydrogen atoms in the ligand.

The docking result was marked off for high-affinity compounds. Subsequently, all possible docked conformers of the hits were splitted for their interaction analysis. All conformers were analyzed using PyMOL and Discovery Studio visualizer to explore their binding pattern and interactions with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. The interaction analysis was performed to get highly selective compounds that preferentially bind to the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro substrate-binding pocket.

2.2. Biological activity predictions and structure-activity analysis

To investigate the biological properties of the selected compounds, we have predicted their possible biological functions through the PASS webserver (Lagunin et al., 2000). The PASS analysis allows for exploring the effects and properties of chemical compounds on the basis of their molecular formula. It uses multilevel neighbors of atoms (MNA) descriptors, suggesting the biological activity of a compound is the function of its chemical structure. It defines the prediction of biological properties of a compound based on the ratio of probability to be active (Pa) and probability to be inactive (Pi). Higher the Pa value for a prediction means the compound is having more probability to be active under that particular activity or biological property. Here, we selected only those compounds showing antiviral properties and protease inhibitory potential and subsequently discussed their analog properties with parent compounds.

2.3. MD simulations

MD simulations were performed on three systems, one, the apo- SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and the other two with the selected ligands, 10428963 and 71481120 for 50 ns at the molecular mechanics level using GROMOS 54A7 force-field in GROMACS 5.1.2 at 300 K. Compounds 10428963 and 71481120 were extracted out from the docked complexes; subsequently, their topology and force-field parameters were produced through the PRODRG webserver and then combined into the Mpro topology to make the Gromacs complexed systems. All three systems were soaked in the Simple Point Charge (spc216) model for solvation and energy minimized using steepest descent approach under 1500 steps. Final MD run was performed for 50,000 ps (50 ns) for each system and the generated trajectories were analyzed using the inbuilt tools of GROMACS as described in our preceding communications (Mohammad et al., 2019; Naqvi et al., 2018).

2.4. Principal component analysis

To study the conformational sampling and atomic motions of Mpro and its docked complexes, principal component (PC) and free energy landscape (FEL) analyses were performed using the essential dynamics approach employing the calculation of the covariance matrix (Altis et al., 2008). The covariance matrix was calculated while using the following formula:

| Cij = < (xi - < xi>) (xj - <xj>) > |

where xi/xj is the coordinate of the ith/jth atom of the systems, and < - > in the ensemble average.

The FELs of a protein can be attained using the conformational sampling approach that allows exploring the protein conformations near the native state (Papaleo et al., 2009). FELs were generated to investigate the stability and native states of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, before and after compounds binding. The FELs were generated as:

| ΔG(X) = -KBT ln P(X) |

where K B is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature of simulation, and P(X) is the probability distribution of the system along with the PCs.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Virtual screening

From the 158 PDB entries of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, a total of 121 unique co-crystallized compounds were selected (Table S1). Redocking of these compounds resulted in the identification of many hits as high-affinity binding ligands of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (Table 1 ). These compounds are showing considerable binding affinities to the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Here, we have selected the top 10 hits with their binding affinities within the range of -8.3 kcal/mol to -7.5 kcal/mol (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of selected hits from the co-crystalized ligands with Mpro showing notable binding affinity*.

| S. No. | Ligand ID (PDB) | Parent Protein ID (PDB) | Common name of the ligand | PubChem ID of ligand | Affinity (kcal/mol) | No. of hits* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3WL | 6M2N | Baicalein | 5281605 | −8.3 | 6930 | |

| T7S | 5RFO | 1-[4-(piperidine-1-carbonyl)piperidin-1-yl]ethan-1-one | 16394003 | −8.3 | 1335 | |

| T47 | 5RET | 1-{4-[(3-chlorophenyl)methyl]piperazin-1-yl}ethan-1-one | 19323586 | −8.2 | 63 | |

| A82 | 6YVF | 2-[[(1R)-1-(7-methyl-2-morpholin-4-yl-4-oxidanylidene-pyrido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-9-yl)ethyl]amino]benzoic acid | 44137675 | −8.1 | 26 | |

| K36 | 7BRR | (1S,2S)-2-({N-[(benzyloxy)carbonyl]-l-leucyl}amino)-1-hydroxy-3-[(3S)-2-oxopyrrolidin-3-yl]propane-1-sulfonic acid | 118737648 | −7.9 | 102 | |

| T1J | 5REC | 2-{[(1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)amino]methyl}phenol | 787400 | −7.8 | 545 | |

| T4V | 5REX | 1-{4-[(naphthalen-1-yl)methyl]piperazin-1-yl}ethan-1-one | 8386889 | −7.7 | 155 | |

| SAM | 6W61 | S-Adenosylmethionine | 34755 | −7.6 | 1375 | |

| SFG | 6YZ1 | Sinefungin | 65482 | −7.5 | 340 | |

| T8A | 5RFT | 1-[(4S)-4-phenyl-3,4-dihydroisoquinolin-2(1 H)-yl]ethan-1-one | 145998233 | −7.5 | 52 |

PubChem hits, the number of the PubChem compounds selected with >90 % similarity (Tanimoto threshold).

3.2. Molecular docking

A total of 10,433 PubChem compounds carrying at least 90 % structural similarity with the top 10 hits were identified and screened for their drug-likeliness. After filtration based on physicochemical, ADMET, and other druglike properties, we got a set of 4802 compounds satisfying the threshold of the applied filters of drug-likeness and RO5. These compounds were further screened out based on their affinities with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro using molecular docking-based virtual screening and selected the top five compounds. These compounds show significant binding affinities toward SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (-8.1 kcal/mol to -8.7 kcal/mol, Table 2 ). The docking analysis suggested that the identified compounds have improved druglike properties compared to their parent compounds reported in the structures of co-crystallized SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

Table 2.

List of selected hits from the PubChem compounds with their affinity and physicochemical properties.

| S. No. | Compound ID (PubChem) | Common name | Affinity (kcal/mol) | LE* | pKi | MW (Da) | xLogP | #HBD | #HBA | Parent compound(PubChem ID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57789333 | Azd-6482 (S) | −8.7 | 0.32 | 6.38 | 408.18 | 2.0 | 2 | 7 | 44137675 | |

| 5481231 | Piscisoflavone B | −8.6 | 0.24 | 6.31 | 366.11 | 3.4 | 2 | 6 | 5281605 | |

| 71481120 | UNII-O9H5KY11SV | −8.4 | 0.27 | 6.16 | 485.18 | 0.7 | 5 | 8 | 118737648 | |

| 54592323 | 2-Fluoro-5′-MethylthioAdo | −8.3 | 0.22 | 6.09 | 383.14 | 2.1 | 3 | 9 | 34755 | |

| 10428963 | 6-Deaminosinefungin | −8.1 | 0.23 | 5.94 | 366.37 | −3.1 | 5 | 10 | 65482 |

Abbreviations: pKi negative decimal logarithm of inhibition constant; MW Molecular weight; #HBD Hydrogen Bond Donor Count; #HBA Hydrogen Bond Acceptor Count. *LE: Ligand Efficiency (kcal/mol/non-H atom).

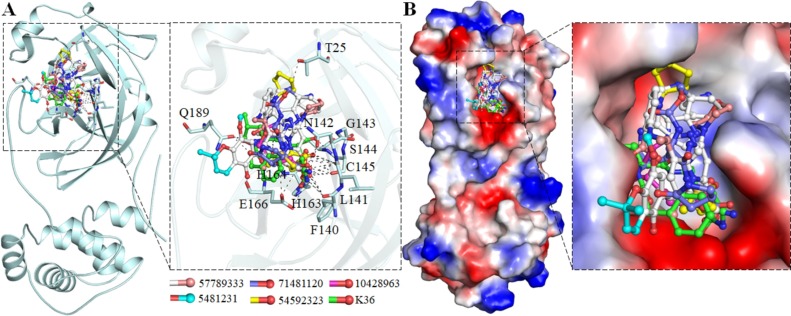

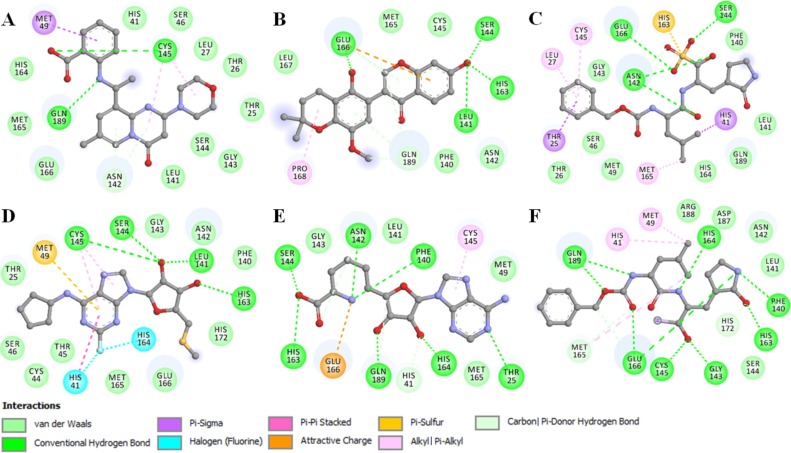

To explore the specific interaction of these five compounds, detailed interaction analysis of their possible docked conformers (9 for each compound) was carried out to find their preferential interaction with the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-binding pocket. We identified that all the selected compounds are showing many specific polar interactions with a set of critical residues, Thr25, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His163, his164, Glu166, Gln189 of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. All these compounds are mimicking the same binding pattern and sharing common interactions as co-crystallized SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor K36 (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Binding pattern of the selected compounds and standard inhibitor K36 with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. (A) Structural representation of the protein in-complexed with all the compounds making significant interactions with the functionally important residues of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro binding pocket. (B) The potential surface of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro showing the binding pocket occupancy by the compounds.

All the compounds binding in the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro substrate-binding pocket were explored for their detailed interaction. All these compounds are showed to have many polar interactions with the critical residues of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro substrate-binding site (Fig. 3 ). They are showing many hydrogen-bonds with Thr25, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His163, his164, Glu166, and Gln189 (Fig. 3). Besides, all compounds occupied a deeper cavity of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro substrate-binding pocket to hinder the substrate-accessibility thus possibly resulted in inhibition of protease activity. All compounds are mimicking of the same orientation and sharing a similar pattern of binding and showing common interactions as most of the co-crystallized inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro binds (Jo et al., 2020).

Fig. 3.

2D plots of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro substrate-binding pocket residues and their interactions with compound (A) 57789333 (B) 5481231 (C) 71481120 (D) 54592323 (E) 10428963 and (F) K36.

In the interaction analysis, we noticed that all the selected compounds are showing many hydrogen and halogen bonding with the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro substrate-binding site. These interactions help to bind the compounds within the substrate-binding pocket and consequently can inhibit the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro activity. The active site of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, Cys145 (originally Cys3408) acts as a nucleophile, and responsible for protease activity is participating in direct interaction with the identified compounds (Zhang et al., 2020). Specific interactions and binding properties of these compounds make them potential leads to develop inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

3.3. Biological activity and SAR analysis

To explore the possible biological activities and antiviral potential of selected ligands, the PASS server prediction was carried. The analysis suggested that the selected compounds are having similar classes of biological activities. We identified two compounds, 10428963 and 71481120 which show antiviral activity through the protease inhibitory potential, with Pa ranging from 0413 to 0,914 when Pa > Pi. The biological activities of the identified compounds with higher Pa value along with their ADMET properties are shown in Table 3 .

Table 3.

List of identified compounds and their biological activities along with ADMET properties.

| S. No. | Compound ID (PubChem) | Pa | Pi | Biological Activity | A | D | M | E | T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10428963 | 0914 | 0002 | Antiviral (Picornavirus) | 34.8 | No | No | No | No | |

| 0894 | 0002 | Antiviral (Poxvirus) | |||||||

| 0544 | 0006 | Antiviral (Herpes) | |||||||

| 0461 | 0007 | Antiviral (Hepatitis B) | |||||||

| 71481120 | 0564 | 0002 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome treatment | 19.7 | No | No | No | No | |

| 0535 | 0002 | SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor | |||||||

| 0479 | 0008 | Antiviral | |||||||

| 0413 | 0004 | Protease inhibitor |

Pa = probability to be active; Pi = probability to be inactive. A: Absorption, GI absorption (%); D: Distribution, CNS & BBB permeability; M: Metabolism, CYP2D6 inhibitor/substrate; E: Excretion, OCT2 substrate; T: Toxicity, AMES & Hepatotoxicity.

The identified compound 10428963, commonly known as 6-Deaminosinefungin ((2S)-2-Amino-6-[(2R,3S,4R,5R)-5-(6-aminopurin-9-yl)-3,4-dihydroxyoxolan-2-yl]hexanoic acid) is a well-known antiviral compound exploited in cancer research (Peterli-Roth et al., 1994). Compound 10428963 is an active analog of S-adenosylmethionine, S-adenosylhomocysteine, and Sinefungin, an antiviral and inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB IDs: SFG, 6YZ1) with improved pharmacological properties (Peterli-Roth et al., 1994).

The compound 71481120 is known as UNII-O9H5KY11SV ((2S)-1-Hydroxy-2-[[(2S)-4-methyl-2-(phenylmethoxycarbonylamino)pentanoyl]amino]-3-(2-oxopyrrolidin-3-yl)propane-1-sulfonic acid) is an antiviral in nature predicted to have possibilities for SARS treatment and appreciable inhibitory potential against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Compound 71481120 is an analog of K36 ((2S)-1-Hydroxy-2-[[(2S)-4-methyl-2-(phenylmethoxycarbonylamino)pentanoyl]amino]-3-[(3S)-2-oxopyrrolidin-3-yl]propane-1-sulfonic acid), co-crystallized with many viral proteases including SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB IDs: K36, 7BRR).

Both the identified compounds are analogs of already known antiviral compounds with admirable protease inhibitory potential, improved pharmacological properties, and considerably high affinity towards SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Both compounds are showing significant interaction with the amino acid residues of the catalytic site, Cys145, and His41, where Cys145 is the active site of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, acts as a nucleophile, and responsible for the protease activity (Zhang et al., 2020). Binding of any compound to these residues will hinder the substrate accessibility and thus inhibition of protease activity of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro similar to the alpha-ketoamide/N3-ILP inhibitors reported (Zhang et al., 2020). All these properties of 10428963 and 71481120 make them potential leads to develop SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors that can be used in the development of safe and effective COVID-19 therapy.

3.4. MD simulations

Three systems, SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-apo, Mpro-10428963, and Mpro-71481pro-71,481,120 complexes were subjected to MD simulation for 50 ns. Different systematic and structural properties of all three systems were explored to ascertain their stability and dynamics under the solvent condition during the simulation time.

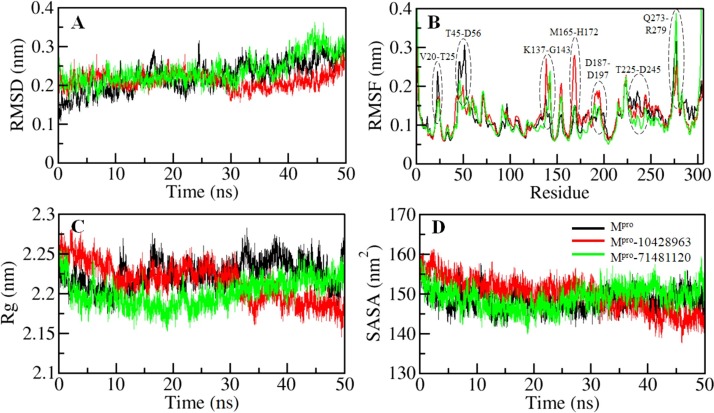

Binding of any small compound can make large changes to a protein structure. Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) is one such fundamental property that can be utilized to investigate structural deviation and compactness of a protein (Turab Naqvi et al., 2019). We explored the structural dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-apo, and in complex with 10428963 and 71481120 by calculating their RMSD. The average RMSD of the Mpro in the free state, Mpro-10428962, and Mpro-71481120 complexes was found as 0.22 nm, 0.21 nm, and 0.23 nm, respectively. While comparing, the RMSD suggests that the Mpro is getting a little stabilized after 10428963 bindings as compared to the Mpro-71481120 complex. The binding of 10428963 and 71481120 cause an infrequently conformational change in Mpro from its native state (Fig. 4 A). The RMSD of Mpro-10428963 is showing a little decrease after 25 ns and equilibrated throughout the entire trajectory, suggesting the durable stability of the complex.

Fig. 4.

Structural dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro as a function of time. (A) Time evolution of the RMSD of Mpro before and after compounds binding. (B) Residual fluctuations plot of Mpro before and after 10428963 and 71481120 bindings. (C) Plot showing the radius of gyration of Mpro before and after 10428963 and 71481120 bindings. (D) SASA plot of Mpro of Mpro before and after 10428963 and 71481120 bindings.

To explore the local fluctuation in Mpro at the residue level, the vibrations in each residue of Mpro before and after compounds binding were explored as root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF). A random distribution of residual fluctuations was observed in Mpro at regions near to N- to C-termini (Fig. 4B). The SARS-CoV-2 Mpro backbone fluctuations were compared with each residue after the binding of compound 10428963 and 71481120. These fluctuations were found to be minimized at several parts in the case of the Mpro-10428962 and Mpro-71481120 complexes. The local residual fluctuations at flap V20-T25, T45-D56, and T225-D245 were decreased after compounds binding. However, the RMSF of the Mpro-10428963 complex was increased at several parts including the flap spanning K137-G143, M165-H172, and D187-D197 with a sharp peak at G170. The average RMSF of the Mpro in the free state, Mpro-10428962 and Mpro-71481120 complexes was found as 0.12 nm, 0. 12 nm, and 0.11 nm, respectively. The RMSF suggested that most fluctuations are reduced in the region where the compounds bind. Decreased fluctuations were observed in Mpro upon 71481120 binding due to ligands adjustment in the Mpro binding pocket. The increased fluctuations observed in the ligand-binding region in the Mpro can be correlated with the docking results where a number close interactions are formed between the protein-ligand which results in local fluctuations as this region of Mpro is directly participating in the ligands interactions when comparing with the other regions in the Mpro.

The radius of gyration (Rg) is associated with the folding state and overall conformation of the proteins which can be used to get deeper insights into their compactness and folding mechanism (Naqvi et al., 2018). We assessed the conformational behavior of apo-Mpro, Mpro-10428962 and Mpro-71481120 systems by computing their average Rg values as 2.22 nm, 2.21 nm, and 2.20 nm, respectively. The analysis shows a minor decrease in the Rg values when in the bound states with the selected compounds. A little decrease in Rg is showing higher compactness of Mpro while its binding pocket is occupied by 10428963 and 71481120. However, initially up to 10 ns, the Mpro in presence of 71481120 was found with an increased Rg which suggesting initial adjustment of Mpro binding pocket occupied with the ligand. Here, no structural shift was observed in Mpro in the presence of the compounds where the Rg is attaining a stable equilibrium, suggests stability of protein-ligand complexes during the entire simulation (Fig. 4C).

The solvent-accessible surface area is calculated as an interface surrounded by a solvent (Ausaf Ali et al., 2014; Rodier et al., 2005). This solvent behaves differently with varying conditions and thus a useful parameter to study the conformational dynamics of a protein in the solvent environment. To investigate the conformational behavior of Mpro before and after the binding of 71481120 and 10428963, we have computed the SASA of all three systems. The average SASA values for apo Mpro, Mpro-10428962 and Mpro-71481120 were found as 148.47 nm2, 149.75 nm2, and 149.04 nm2, respectively. A minor increase in the SASA of Mpro while binds with the compounds were observed possibly due to the exposure of some inner residues to the protein surface (Fig. 4D). The plot suggests that SASA attained an equilibrium without switching throughout the simulation signifying structural stability of Mpro before and after 10428963 and 71481120 bindings.

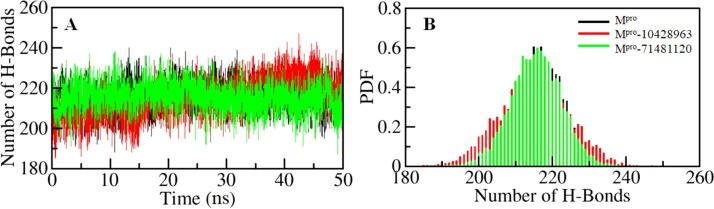

Intramolecular hydrogen bonding within protein molecules plays a fundamental role to stabilize their three-dimensional structure (Hubbard and Kamran Haider, 2001; Naz et al., 2018, 2017). To validate the stability of Mpro and its ligand-bound complexes, we have calculated the dynamics of intramolecular hydrogen bonds paired within 3.5 Å. The computed average number of intramolecular hydrogen bonds in Mpro apo, Mpro-10428962 and Mpro-71481120 was found to be 216 and 215, 215, respectively ( Fig. 5 A). A slight decrease in the number of average hydrogen bonds within Mpro itself is due to the occupancy of some intramolecular space of the binding pocket by compound 10428963 and 71481120. The Probability distribution function (PDF) analysis of H-bond dynamics shows that the complexes of Mpro-10428962 and Mpro-71481120 are quite stable during the entire simulation (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Structural compactness of Mpro before and after 10428963 and 71481120 binding. (A) Time evolution of hydrogen bonds formed intramolecular within Mpro (B) The PDF of intramolecular Hydrogen bonds.

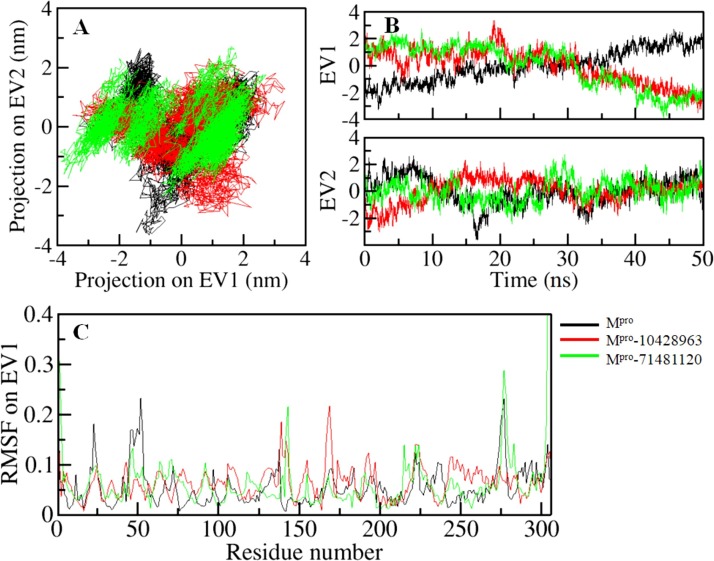

3.5. Principal component and free energy landscape analysis

The dynamics of a protein structure can be illustrated through their phase space performance. We did PCA to study the conformational sampling of Mpro in the free state as well as in complexed states with 10428963 and 71481120 via studying their collective motions while using the essential dynamics approach (Amadei et al., 1993). The PCA analysis allows us to explore the dynamic motion and flexibility of a protein structure in conformational space. The conformational sampling of Mpro and its docked complexes in the essential subspace is illustrated in Fig. 6 A. This projection shows the structural conformations of Mpro along with the eigenvector (EV)-1 and EV-2 projected by Cα atoms. Here, we observed that the Mpro-10428962 and Mpro-71481120 complex occupied the same conformational subspace as Mpro in the free state. An increased dynamic was observed at EV1 in the case of the complexes, but no overall shift of the Mpro in complexed with 10428963 and 71481120 was observed at both EVs (Fig. 6B). Both complexes are overlapping the stable clusters with phase space of Mpro-apo in the free state. PCA analysis including the RMSF indicates that Mpro and its complexes are pretty stable during the entire simulation.

Fig. 6.

Principal component analysis. (A) 2D projections of trajectories on eigenvectors (EVs) showing conformational projections of Mpro (B) The projections of trajectories on both EVs with respect to time (C) Residual fluctuations of Mpro on eigenvector 1.

To study the conformational behavior and native states of Mpro and its complexes, the FELs were created using the first two EVs. The FELs of apo Mpro, Mpro-10428962, and Mpro-71481120 complex systems are shown in Fig. 7 . When studying the plots, a deeper blue color is signifying the conformational states with lower energy near to native states. We observed that Mpro is having only a single global minimum confined within a local basin. Similarly, Mpro in presence of 10428963 and 71481120 doesn’t acquire multiple minima and showing single minima but different conformational motion. Both complexes didn’t go to the development of multiple minima and showing a single global state. The plots suggest that the binding of 10428963 and 71481120 to Mpro affects the size and the location of the sampled essential subspace but with a stable single global minimum ( Fig. 7B-C).

Fig. 7.

The Gibbs energy landscapes for (A) free Mpro (B) Mpro-and 10428963 (C) Mpro-71481120.

Altogether, the drug-like properties including physicochemical and ADMET properties, higher and specific binding towards the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro substrate-binding site, and stability during MD simulation studies suggest that 6-Deaminosinefungin (PubChem ID: 10428963) and UNII-O9H5KY11SV (PubChem ID: 71481120) can act as potential leads in drug development against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Both compounds are analogs of known antivirals and showing admirable protease inhibitory potential with improved pharmacological properties and considerably high affinity and stability with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. These findings may be further implemented in the development of effective therapeutics to Covid-19 after required experimental validation.

4. Concluding remarks

In this study, we extensively analyzed the available SARS-CoV-2 Mpro structures, co-crystallized with different molecules and inhibitor-like compounds investigate their binding pattern and mechanism of inhibition. We utilized the structural information of co-crystallized Mpro structures to find high-affinity SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors from the PubChem database. The compounds were further screened for their physicochemical properties, drug-likeliness, and molecular interactions with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Finally, we identified two compounds, 6-Deaminosinefungin (PubChem ID: 10428963) and UNII-O9H5KY11SV (PubChem ID: 71481120) showing the high binding affinity and interact to the conserved residues of the substrate-binding pocket of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Both compounds are analogs of known antiviral compounds with protease inhibitory potential and improved pharmacological properties. All-atom MD simulation studies suggested complex stability of Mpro in the presence of both compounds with minimal structural changes.

Funding

This work is funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Taj Mohammad: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Visualization. Anas Shamsi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Saleha Anwar: Methodology, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Visualization, Software, Validation, Investigation. Mohd. Umair: Methodology, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Software, Validation. Afzal Hussain: Methodology. Md. Tabish Rehman: Validation, Visualization. Mohamed F. AlAjmi: Software, Writing - review & editing. Asimul Islam: Validation, Data curation, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Md. Imtaiyaz Hassan: Conceptualization, Validation, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

TM and AS are thankful to the University Grants Commission, India for the award of Fellowships. Authors thank the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India for the FIST support (FIST program No. SR/FST/LSI-541/2012). MFA, MTR, and AH acknowledge the generous support from Research Supporting Project (No. RSP-2020-122) by King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198102.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Altis A., Otten M., Nguyen P.H., Hegger R., Stock G. Construction of the free energy landscape of biomolecules via dihedral angle principal component analysis. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128 doi: 10.1063/1.2945165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadei A., Linssen A.B., Berendsen H.J. Essential dynamics of proteins. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 1993;17:412–425. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand K., Ziebuhr J., Wadhwani P., Mesters J.R., Hilgenfeld R. Coronavirus main proteinase (3CLpro) structure: basis for design of anti-SARS drugs. Science. 2003;300:1763–1767. doi: 10.1126/science.1085658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausaf Ali S., Hassan I., Islam A., Ahmad F. A review of methods available to estimate solvent-accessible surface areas of soluble proteins in the folded and unfolded states. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2014;15:456–476. doi: 10.2174/1389203715666140327114232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biovia D.S. Dassault Systèmes; San Diego: 2015. Discovery Studio Modeling Environment. [Google Scholar]

- Chary M.A., Barbuto A.F., Izadmehr S., Hayes B.D., Burns M.M. COVID-19: Therapeutics and their toxicities. J. Med. Toxicol. 2020;16(10):1007. doi: 10.1007/s13181-020-00777-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai W., Zhang B., Jiang X.-M., Su H., Li J., Zhao Y., Xie X., Jin Z., Peng J., Liu F. Structure-based design of antiviral drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science. 2020;368:1331–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan W.-j., Ni Z.-y., Hu Y., Liang W.-h., Ou C.-q., He J.-x., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C.-l., Hui D.S. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Zhou Y., Liu S., Kou Z., Li W., Farzan M., Jiang S. Receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV spike protein induces highly potent neutralizing antibodies: implication for developing subunit vaccine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;324:773–781. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins A.L., Groom C.R., Alex A. Ligand efficiency: a useful metric for lead selection. Drug Discov. Today. 2004;9:430. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard R.E., Kamran Haider M. eLS (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd); 2001. Hydrogen Bonds in Proteins: Role and Strength. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob R.B., Andersen T., McDougal O.M. Accessible high-throughput virtual screening molecular docking software for students and educators. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S., Kim S., Shin D.H., Kim M.S. Inhibition of SARS-CoV 3CL protease by flavonoids. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020;35:145–151. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2019.1690480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan P., Queen A., Mohammad T., Smita Khan N.S., Hafeez Z.B., Hassan M.I., Ali S. Identification of α-Mangostin as a potential inhibitor of microtubule affinity regulating kinase 4. J. Nat. Prod. 2019;82:2252–2261. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagunin A., Stepanchikova A., Filimonov D., Poroikov V. PASS: prediction of activity spectra for biologically active substances. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:747–748. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.8.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Xiao X., Wei X., Li J., Yang J., Tan H., Zhu J., Zhang Q., Wu J., Liu L. Composition and divergence of coronavirus spike proteins and host ACE2 receptors predict potential intermediate hosts of SARS‐CoV‐2. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G., Wang Q., Gao G.F. Bat-to-human: spike features determining ‘host jump’of coronaviruses SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and beyond. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:468–478. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., Wang Y., Wang W., Nie K., Zhao Y., Su J., Deng Y., Zhou W., Li Y., Wang H. Complete genome sequence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) from the first imported MERS-CoV case in China. Genome Announc. 2015;3:e00818–00815. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00818-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H., Wang W., Song H., Huang B., Zhu N. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakshi R., Padhan K., Rehman S., Hassan M.I., Ahmad F. The SARS Coronavirus 3a protein binds calcium in its cytoplasmic domain. Virus Res. 2014;191:180–183. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad T., Khan F.I., Lobb K.A., Islam A., Ahmad F., Hassan M.I. Identification and evaluation of bioactive natural products as potential inhibitors of human microtubule affinity-regulating kinase 4 (MARK4) J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019;37:1813–1829. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2018.1468282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad T., Arif K., Alajmi M.F., Hussain A., Islam A., Rehman M.T., Hassan I. Identification of high-affinity inhibitors of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-3: towards therapeutic management of cancer. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1711810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi A.A., Mohammad T., Hasan G.M., Hassan M. Advancements in docking and molecular dynamics simulations towards ligand-receptor interactions and structure-function relationships. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2018;18:1755–1768. doi: 10.2174/1568026618666181025114157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi A.A.T., Fatima K., Mohammad T., Fatima U., Singh I.K., Singh A., Atif S.M., Hariprasad G., Hasan G.M., Hassan M.I. Insights into SARS-CoV-2 genome, structure, evolution, pathogenesis and therapies: structural genomics approach. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020;1866 doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naz H., Khan P., Tarique M., Rahman S., Meena A., Ahamad S., Luqman S., Islam A., Ahmad F., Hassan M.I. Binding studies and biological evaluation of beta-carotene as a potential inhibitor of human calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;96:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naz F., Khan F.I., Mohammad T., Khan P., Manzoor S., Hasan G.M., Lobb K.A., Luqman S., Islam A., Ahmad F. Investigation of molecular mechanism of recognition between citral and MARK4: a newer therapeutic approach to attenuate cancer cell progression. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;107:2580–2589. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaleo E., Mereghetti P., Fantucci P., Grandori R., De Gioia L. Free-energy landscape, principal component analysis, and structural clustering to identify representative conformations from molecular dynamics simulations: the myoglobin case. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2009;27:889–899. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterli-Roth P., Maguire M.P., Leon E., Rapoport H. Syntheses of 6-Deaminosinefungin and (S)-6-Methyl-6-deaminosinefungin. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:4186–4193. [Google Scholar]

- Rodier F., Bahadur R.P., Chakrabarti P., Janin J. Hydration of protein–protein interfaces. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2005;60:36–45. doi: 10.1002/prot.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamsi A., Mohammad T., Anwar S., AlAjmi M.F., Hussain A., Rehman M., Islam A., Hassan M. Glecaprevir and Maraviroc are high-affinity inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease: possible implication in COVID-19 therapy. Biosci. Rep. 2020;40 doi: 10.1042/BSR20201256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheahan T.P., Sims A.C., Leist S.R., Schäfer A., Won J., Brown A.J., Montgomery S.A., Hogg A., Babusis D., Clarke M.O. Comparative therapeutic efficacy of remdesivir and combination lopinavir, ritonavir, and interferon beta against MERS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13940-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O., Olson A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turab Naqvi A.A., Jairajpuri D.S., Ali Noman O.M., Hussain A., Islam A., Ahmad F., Alajmi M.F., Hassan M.I. Evaluation of pyrazolopyrimidine derivatives as microtubule affinity regulating kinase 4 inhibitors: towards therapeutic management of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019:1–19. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2019.1666745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Wong G., Lu G., Yan J., Gao G.F. MERS-CoV spike protein: targets for vaccines and therapeutics. Antiviral Res. 2016;133:165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S.K., Li W., Moore M.J., Choe H., Farzan M. A 193-amino acid fragment of the SARS coronavirus S protein efficiently binds angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:3197–3201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300520200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Goldsmith J.A., Hsieh C.-L., Abiona O., Graham B.S., McLellan J.S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.-Z., Holmes E.C. A genomic perspective on the origin and emergence of SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2020;181:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Lin D., Sun X., Curth U., Drosten C., Sauerhering L., Becker S., Rox K., Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;368:409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.-R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.-L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.