Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Understanding whether family members’ experiences with patients’ treatment for end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) were expected could guide the development of family-centered interventions that enhance the preparedness of patients and their care partners for kidney replacement therapies. We explored unexpected negative experiences with ESKD treatments among family members of dialysis and posttransplantation patients to identify meaningful directions for family-centered research and clinical care.

Study Design

Qualitative study.

Setting & Participants

8 focus groups comprising 49 family members of dialysis patients and living donor kidney transplant recipients undergoing medical care in Baltimore, MD.

Analytical Approach

Focus groups were stratified by patients’ treatment (in-center hemodialysis, home hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or living donor kidney transplantation) and family members’ self-reported race (African American vs non–African American), resulting in 2 groups per treatment experience. Inductive thematic analysis was used to identify themes in focus group transcripts. Themes shared across different treatment groups were highlighted to provide insight into common experiences.

Results

We identified 4 themes that described family members’ unexpected negative treatment experiences: becoming a care partner (unanticipated responsibilities and sleep disruptions), adverse psychological treatment responses in patients (eg, depression) and family members (eg, anxiety), treatment delivery and logistics (insufficient information, medication regimen, and logistical inconveniences), and patient morbidity (dialysis-related health problems and fatigue). All themes were relevant to discussions in the in-center hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and transplantation groups, whereas psychological responses and morbidity themes did not reflect discussions in home hemodialysis groups.

Limitations

Data collection occurred from 2008 to 2009; family members were recruited through patients undergoing care in 1 geographic area; 1 family member participant per patient.

Conclusions

Family members described a broad range of unexpected negative experiences with ESKD treatments. Efforts to prepare families for ESKD treatments through more family-centered care, early and tailored education, and interventions targeting care partner preparedness, health provider–family member communication, and relationship dynamics in family member–patient dyads are needed.

Index Words: End-stage kidney disease treatments, unexpected experiences, families, dialysis, living-donor kidney transplantation

Family members often become involved in patients’ treatment for end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) as care partners. As care partners, family members engage in a multitude of essential activities, some of which include administering medication; overseeing treatment adherence; assisting with usual activities and treatment delivery; scheduling, providing transportation to, and attending medical appointments; monitoring patients’ health; advocating for patients; and offering emotional support.1 These activities benefit patients and health providers alike. For patients, family member involvement is associated with improved self-management behaviors and treatment adherence, enhanced quality of life, decreased mortality risk, reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms, and lower odds of 30-day hospital readmission.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 For health providers, family members are invaluable allies in the task of caring for patients with ESKD.7

Although involvement in patients’ treatment can be rewarding for family members (eg, developing a sense of self-worth), several studies have shown that it can also impose burdens on them (eg, financial), jeopardize their health (eg, physical injuries) and well-being (eg, depression), and conflict with their other roles or responsibilities (eg, work performance).1, 8, 9, 10 Additionally, family members have consistently received little attention in both research and practice.11 Unsurprisingly, family members convey uncertainty about their role in patients’ care, describe feeling overlooked and being treated poorly by health care providers, encounter difficulties accessing the health care system, lack treatment-related and disease-related knowledge, and report unmet support needs.9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15

Given that family members affect and are affected by patients’ treatment for ESKD, it is imperative to understand how best to support them. One approach to understanding how to optimally support these family members is to acquire insight into the expectedness of their experiences with ESKD treatments. This insight could guide the development of interventions that enhance family members’ treatment preparedness. In other illness populations, family members equate knowing what to expect in the future with feelings of preparedness, whereas uncertainty about the future is considered a source of worry.16 In addition, their feelings of unpreparedness have been associated with depression, anxiety, distress, burden, poorer quality of life, and fewer care partner rewards.17, 18, 19, 20 Interventions targeting preparedness for ESKD treatments therefore have the potential to improve family members’ psychological well-being, care partner experiences, and quality of life. Thus, we explored unexpected negative treatment experiences among family members of dialysis and posttransplantation patients to identify meaningful directions for family-centered research and clinical care.

Methods

Study Design

Data derive from an ancillary study of the Providing Resources to Enhance African American Patients’ Readiness to Make Decisions About Kidney Disease (PREPARED) trial, which developed and tested culturally sensitive informational and financial interventions to enhance shared and informed decision-making about ESKD treatment among patients and their families. A detailed protocol for the trial is published elsewhere.21 The ancillary study informed the development of intervention content and entailed 8 focus groups that explored family members’ perceptions of and experiences with ESKD treatments. Groups were stratified by patients’ treatment in the past year (in-center hemodialysis, home hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or living donor kidney transplantation) and family members’ self-reported race (African American or non–African American), which resulted in 2 groups per treatment. Although focus groups were stratified by race, exploration of race differences was an objective of the PREPARED study and not an objective of this study.

The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board (#00022055) and follows the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist.22

Participants

Focus group recruitment procedures have been detailed elsewhere.21, 23, 24, 25 Briefly, trained research staff recruited family members for study participation by contacting patients with ESKD in the Baltimore, MD, metropolitan area. Staff members were not involved in patient care and did not know patients before approaching them about study inclusion. Staff approached patients face to face in purposely selected community-based and academic nephrology practices to facilitate the engagement of an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse population. Eligible patients spoke English, were at least 18 years of age, and had been undergoing dialysis for at least 1 year or had received a kidney from a living donor in the past year (posttransplantation). Recruitment sites provided lists of potentially eligible patients based on these criteria. Patients provided staff with contact information for 1 English-speaking family member or friend (hereafter called “family member”) involved in their treatment decisions. Staff called family members to ascertain their interest in attending 1 focus group. If family members agreed to participate, staff obtained and documented informed oral consent at the time of the call. Reasons for nonparticipation included the inability to attend a meeting on the date and time that worked for most participants.

Data Collection

Focus group meetings occurred between October 2008 and March 2009 at academically affiliated medical centers at which patients received their medical care. Data collection was undertaken by a female senior research nurse and female research assistant, both of whom hold Master’s degrees in Health Science. The senior research nurse, an experienced qualitative researcher, trained the research assistant in the conduct of focus groups. They each conducted the 90-minute focus group meetings and had no previous relationship with family members. Only moderators and family members were present during meetings. Before discussions, family members completed a brief questionnaire assessing their sociodemographic characteristics and relation to patient participants. Moderators then assigned each family member a unique numeric identifier. Family members replaced their names with the identifier to preserve confidentiality when speaking.

Moderators initiated discussions using a scripted interview guide (Item S1). The research team developed the guide to pose several questions that reflected the aims of the PREPARED trial.21 The trial was based on key aspects of the PRECEDE-PROCEED model in behavioral theory; focus group questions addressed predisposing factors (eg, knowledge) within the model.21, 26

The guide included introduction, discussion, and conclusion phases. In the introduction phase, moderators provided a brief overview of the research team and reiterated the rationale for the meeting. During the discussion phase, moderators posed the following question: “After your family member or friend started dialysis/received their transplant, were there negative things about dialysis/transplantation that you did not expect?” Other questions from the discussion phase are not relevant here and have been examined elsewhere.23, 24, 25 In the conclusion phase, family members were asked if they had additional comments and then received $50 for their participation. Discussions were audiorecorded and subsequently transcribed by an external service. Field notes were also taken during the data collection process.

Data Analysis

Using inductive thematic analysis procedures,27 N.D. and A.C. independently read the same transcript line by line, identified descriptive themes and subthemes, and developed a preliminary coding scheme. They manually coded the data in Microsoft Word and organized codes in Microsoft Excel. Following preliminary coding, N.D. and A.C. met to compare their codes and establish consensus. They then applied their preliminary coding scheme to another transcript. Any changes were discussed, agreed on, and documented. They repeated this iterative systematic process for the remaining transcripts. Coding saturation was achieved after N.D. and A.C. reviewed all transcripts and agreed that additional coding modifications were unnecessary. N.D. selected exemplar quotations to illustrate themes. Family members were not involved in the analysis process or in confirming the accuracy of transcripts and findings. To provide insight into common perspectives, we present themes relevant to discussions from different treatment groups.

Results

Family Member Characteristics

Through 55 patient participants, 49 family members participated in 8 focus groups. Family members ranged in age from 20 to 83 years, with an average age of 56 years. The majority were African American, women, married or living with a partner, college educated, and medically insured. Most family members identified as patients’ spouses or partners, followed by siblings, parents or parents-in-law, friends, children, and cousins, respectively. Three to 11 family members participated in each group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Family Member Characteristics Overall and by Treatment-Based Focus Group Assignment

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 49) | Treatment-Based Focus Group Assignment |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-Center Hemodialysis (n = 13) | Home Hemodialysis (n = 6) | Peritoneal Dialysis (n = 10) | Posttransplantation (n = 20) | ||

| Age,a y | 56 [23-80] | 59 [44-80] | 42 [37-52] | 59 [45-75] | 55 [23-79] |

| Race | |||||

| African American | 26 (53%) | 7 (54%) | 3 (50%) | 7 (70%) | 9 (45%) |

| White | 19 (39%) | 6 (46%) | 1 (17%) | 2 (20%) | 10 (50%) |

| Other | 4 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (33%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (5%) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 31 (63%) | 10 (77%) | 6 (100%) | 7 (70%) | 8 (40%) |

| Education | |||||

| High school graduate | 20 (41%) | 9 (69%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (40%) | 7 (35%) |

| At least 2 y of college | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (33%) | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| ≥College degree | 26 (53%) | 4 (30%) | 4 (67%) | 5 (50%) | 13 (65%) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/living with partner | 36 (73%) | 9 (69%) | 4 (66%) | 7 (70%) | 16 (80%) |

| Divorced/separated | 5 (10%) | 2 (15%) | 1 (17%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (10%) |

| Never married | 5 (10%) | 2 (15%) | 1 (17%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (5%) |

| Widowed | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (5%) |

| Health insurancea | |||||

| Insured | 47 (96%) | 11 (85%) | 6 (100%) | 10 (100%) | 20 (100%) |

| Relationship to patient | |||||

| Spouse/partner | 23 (47%) | 5 (38%) | 3 (50%) | 4 (40%) | 11 (55%) |

| Sibling | 8 (16%) | 2 (15%) | 2 (33%) | 4 (40%) | 0 (0%) |

| Parent/parent-in-law | 7 (14%) | 3 (23%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (20%) |

| Friend | 6 (12%) | 1 (8%) | 1 (17%) | 2 (20%) | 2 (10%) |

| Child | 3 (6%) | 2 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) |

| Cousin | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (10%) |

Note: Values given as number (percentage) except for age, which is given as mean [range]. Focus groups were stratified by patients’ treatment experiences in the past year (in-center hemodialysis, home hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and living donor kidney transplantation or posttransplantation) and family members’ self-reported race (African American or non–African American), thereby resulting in 8 focus groups, with 2 groups per treatment experience. The number of participants identifying as African American signifies the number of people who participated in 1 treatment group and the number identifying as white or other signifies the number of people who participated in the accompanying treatment group for a given treatment experience.

Missing data for age (in-center hemodialysis, n = 2; home hemodialysis, n = 3; peritoneal dialysis, n = 4; posttransplantation, n = 3) and health insurance (in-center hemodialysis, n = 1).

Unexpected Negative Experiences With ESKD Treatments

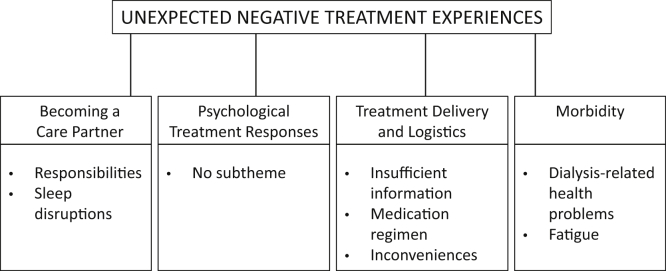

Four themes applied to family members’ discussions about unexpected negative experiences with ESKD treatments: (1) becoming a care partner, (2) psychological responses to treatment, (3) treatment delivery and logistics, and (4) morbidity (Table 2). A summary of these themes and their respective subthemes is presented in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Unexpected Negative Treatment Experiences Among Family Members of Dialysis and Posttransplantation Patients, Organized by Themes and Subthemes

| Subthemes | Focus | Illustrative Quotations | Contributing Groups |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD | HHD | PD | T | |||

| Becoming a care partner | ||||||

| Responsibilities | Family members | “I’d say the other negative thing, now that he’s had 3 transplants, it has made it hard for him to manage his own health because it’s not something that you would let your kid just organize their own medicine, so of course I have to get through the many things. So there’s been a lot of, you know, need to really be an advocate for him and help him to maintain his own health and I’ve seen what it looks like when teens are left to their own devices. So that’s been hard—it’s made him very dependent and that’s okay, you know, if he was a regular 18-year-old he would probably be more independent.” (T) | • | • | • | • |

| Sleep disruptions | Family members | “I don’t rest well if she is on the machine because I never know if she is going to black out or get a clot.” (HHD) | • | • | ||

| Psychological responses to treatment | ||||||

| None | Family members and patients | “Also, just, sometimes I think he's, you know, depressed or just, you know, just so lost.” (HD) | • | • | • | |

| Treatment delivery and logistics | ||||||

| Insufficient treatment information | Family members and patients | “For me—which I didn’t expect—was when I went to the ICU to see her the first time and seeing all the tubes coming out of her. If I had a little bit better picture of that, that probably wouldn’t have caught me off guard as bad.” (T) | • | • | • | |

| Medication regimen | Family members and patients | “I was just astounded at the amount of medication he had to take. My daughter had a liver transplant last year and he has more medication than she does.” (T) | • | • | ||

| Inconveniences | Family members and patients | “I agree with what both of them said [about treatment supplies]. I have a problem with the boxes and we don’t use the basement because sometimes I get water in my basement so he has them upstairs in the hallway. That’s a problem.” (HHD) | • | • | ||

| Morbidity | ||||||

| Dialysis-related health problems | Patients | “My son ended up worse with more illnesses and more symptoms and more things since the dialysis.” (HD) | • | • | • | |

| Fatigue | Family members and patients | “I just know that sometimes he gets really, really tired and I don’t know if he knew that ahead of time or not.” (PD) | • | • | ||

Abbreviations: HD, in-center hemodialysis; HHD, home hemodialysis; ICU, intensive care unit; PD, peritoneal dialysis; T, posttransplantation.

Figure 1.

Summary of themes reflecting family members’ unexpected negative experiences with end-stage kidney disease treatments.

Theme 1: Becoming a Care Partner

The care partner theme reflected family members’ unpreparedness to assume the care partner role and related responsibilities. Some family members unexpectedly became vigilant care partners, meaning that they felt responsible for care partner tasks despite not being physically engaged in them. Being a vigilant care partner disrupted sleep/wake patterns.

Responsibilities

Family members in each treatment group discussed newfound care partner responsibilities. Some family members had not expected to become involved in patients’ care:

“I didn’t expect to have to be involved. I just thought I would have to be there.” (home hemodialysis group)

They described a range of care partner responsibilities, including making frequent trips to the hospital, advocating for dependent patients, organizing medication, operating dialysis machines, and overseeing patients’ treatment adherence. At times, these responsibilities frustrated family members:

Participant: “One negative is getting my husband to do [treatment].”

Interviewer: “You didn’t expect to have to keep him on a schedule?”

Participant: “No…if I was a patient, I would eat exactly what they said—I would be right on the line and he’s right off the line…I wouldn’t do that. And he just—he won’t listen.” (Peritoneal dialysis group)

More complex and urgent activities, such as assisting home hemodialysis patients with rinse-back procedures during power outages, generated feelings of discomfort and uncertainty:

“The nurse was talking about certain situations happening and you have to hurry and it just sounded so urgent and it was really freaking me out. I really don’t feel qualified medically to do any of this stuff and all of the medical terminology that they are using and technical terms and stuff, so I just feel uncertain. They are trained and know that stuff and we don’t.” (Home hemodialysis group)

Sleep Disruptions

Care partner responsibilities disrupted the sleep/wake patterns of family members in the in-center and home hemodialysis groups. Family members awakened to tend to patients returning home from late-night in-center hemodialysis treatment, which resulted in sleep loss:

“I couldn’t even sleep because once he came home…I always had something hot for him to drink.” (in-center hemodialysis group)

Family members of home hemodialysis patients struggled to adjust to nighttime treatment schedules. Other family members experienced difficulties initiating and maintaining sleep because they worried that patients would need their help:

“Right now he has the machine in the bedroom. I lay down on the bed, but my ear—like yesterday…he called me and I jumped right up. I hit the floor as soon as he called my name for some reason because I am listening.” (Home hemodialysis group)

Theme 2: Psychological Responses to Treatment

Family members in the in-center hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and posttransplantation groups talked about their own and patients’ psychological responses to treatment. Not knowing whether treatment would be effective or successful was distressing for family members:

“The anxiety of being that 2 [transplanted kidneys] rejected before—would you get past the safe zone and are you past the safe zone—stop calling me and asking me if I’m past the safe zone.” (Posttransplantation group)

Family members also described unexpectedly hearing about and witnessing patients’ adverse psychological reactions to treatment, which included depression, a negative outlook toward the future, and difficulties psychologically detaching from treatment:

“She basically speaks of being tired of the constant routine. The demanding routine…never-quite-getting-away-from-it-mentally…it’s just constant and it wears on you and not being able to see—I’m guessing from one of the things she’s told me and how she’s reacted—also not seeing any future change in it, like not an end to it.” (Peritoneal dialysis group)

Theme 3: Treatment Delivery and Logistics

The treatment delivery and logistics theme depicted family members’ perceptions of treatment situations they considered problematic, challenging, or inconvenient for themselves and patients alike.

Insufficient Information

Family members in the in-center hemodialysis, home hemodialysis, and posttransplantation groups attributed a lack of information from health care providers to their surprise regarding the large size of dialysis needles, the intensive care environment (eg, seeing patients connected to equipment postsurgery), and medication side effects (eg, patients’ weight gain). For example:

Participant: “Well, I guess maybe if I was prepped by a doctor, or I was there when he was being told there was a weight gain, you know.”

Interviewer: “And that was something they hadn’t told you before?”

Participant: “Yeah.” (Posttransplantation group)

Family members also discussed the inadequacies of informational materials about operating dialysis machines at home. These inadequacies complicated treatment delivery:

“And the language in the book when it gives you a code red—why can’t they just use layman’s terms? Just make it plain. The book is not even right. Sometimes they tell you to turn the machine off but they really didn’t mean that. They meant for you to do something else before you turn the machine off. The book is not consistent, so how are you supposed to do things?” (Home hemodialysis group)

Medication Regimen

The amount of medication prescribed to in-center hemodialysis and posttransplantation patients, along with the complexity of their medication regimen, astounded family members. Medications and medication doses changed frequently, which created adjustment difficulties:

“After surgery the only negative thing I could say we had was so many medications…It’s constantly juggling that. I mean, it’s always up here, down here…so it’s always all over the place.” (Posttransplantation group)

Logistical Inconveniences

Family members in the home hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis groups identified listening to noisy dialysis machines and storing treatment supplies as unanticipated logistical inconveniences. For example, 1 participant said:

“The space that it takes to store 3,000 cases of stuff is unbelievable. I walk in and I am like, ‘What are all of these boxes?’ And boxes are constantly delivered and it is like I guess whatever the supplies are, water and things…the whole entire wall of our basement just covered with the cases of the material. We don’t have parties downstairs anymore because of the machine and all of the supplies.” (Home hemodialysis group)

Theme 4: Morbidity

The morbidity theme encompassed family members’ perceptions of patients’ experiences with dialysis-related health problems and fatigue.

Dialysis-Related Health Problems

Family members in the in-center hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and posttransplantation groups had not foreseen patients experiencing new or additional health problems after undergoing dialysis. One particularly serious health problem was high blood pressure:

“He was diagnosed with high blood pressure and he has problems with that now. His blood pressure goes extremely high and he didn't have that problem before.” (In-center hemodialysis group)

Family members believed that these unforeseen health issues posed a potential threat to the physical health of posttransplantation patients who had previously undergone dialysis:

“The other thing is, depending on how long you’ve been in dialysis, the deterioration that it does to the body. There are a lot of other issues related to that and those are not healed. There are some other physical problems that are a result of the dialysis, not the kidney transplant, but it was all tied together.” (Posttransplantation group)

Fatigue

Family members did not expect in-center hemodialysis and peritoneal patients to nap frequently and exhibit low energy levels following treatment:

“My son was so tired and by me not being around people, you know before, I didn’t know better and I didn’t expect him to be that tired from the treatment.” (In-center hemodialysis group)

Discussion

Family members described a broad range of unexpected negative experiences with ESKD treatments that spanned becoming a care partner, psychological reactions, treatment delivery and logistics, and morbidity. However, within this broad range, the majority of family members’ experiences pertained to how treatments unexpectedly affected their daily lives, disrupted accustomed routines, induced negative emotions, and imposed practical challenges and inconveniences. These areas of emphasis may stem from a mismatch between aspects of ESKD treatments prioritized by health care providers and those prioritized by patients’ families.28 Specifically, health care providers tend to prioritize illness and clinical factors such as biochemical targets, mortality, and adverse events, whereas family members typically focus on both wellness and illness, at times favoring considerations for daily life and well-being.15, 23, 28, 29, 30 If health care providers disseminate treatment information heavily oriented toward illness and clinical factors, they may leave family members unprepared for impending treatment experiences that matter to them. Consequently, family members encounter the unexpected, which may hinder their abilities to integrate the patient’s illness and treatment into their lives.16 These findings underscore the importance of health care providers engaging in efforts to minimize the mismatch between their own treatment information priorities and those of their patients’ families (Box 1).

Box 1. Recommendations for Helping Family Members Know What to Expect From End-Stage Kidney Disease Treatment.

Recommendations for Health Care Providers

-

•

Health care providers should minimize the mismatch between their own and family members’ treatment information priorities by disseminating family-centered treatment information

-

•

Health care providers can use the unexpected negative treatment experiences described here to facilitate preparatory discussions with family members (eg, discuss likely care partner responsibilities or activities)

Recommendations for Educational Resources

-

•

Expand educational resources about end-stage kidney disease treatments to include family-level implications of treatment decisions (eg, possible changes in sleep patterns for family members of home hemodialysis patients)

-

•

Orient educational programs or training sessions toward families or potential care partners (eg, account for family members’ feelings of uncertainty about assisting with treatment delivery)

Recommendations for Intervention Development and Future Research

-

•

Develop interventions that target adaptive coping skills (eg, problem-focused coping strategies) and emotion transmission in the family member–patient dyad

-

•

Acquire a deeper understanding of communication about treatment-related information between patients and their family members, as treatment-related information sharing and communication within families may help family members feel more prepared for treatment experiences

Notably, family members explicitly attributed some unexpected experiences to a lack of forewarning from health care providers. This finding indicates that families are not receiving needed or desired treatment-related anticipatory guidance from health care providers. Health care providers can use the themes presented here as a starting point for considering discussion topics that may facilitate family members’ receipt of desired preparatory information. In particular, findings suggest that becoming a care partner constitutes a significant anticipatory guidance topic for families. Beyond interactions with health care providers, expanding educational resources about ESKD treatments to include family-level implications of treatment decisions may help family members prepare for care partner responsibilities.

Another strategy entails orienting educational programs toward families or potential care partners and detailing responsibilities they may assume.31, 32 For instance, efforts could focus on family members’ educational needs for home hemodialysis training sessions because this is an important but rarely explored topic.33 Family members in this study found training sessions to be intimidating and nerve-racking, both of which could detract from their comprehension of and comfort with care partner responsibilities.

Further, findings indicate that interventions designed to enhance care partner preparedness should help family members manage their own and patients’ adverse psychological treatment responses. While other studies have similarly observed negative psychological reactions to ESKD among patients and their family members,1 this study extends prior work by showing that these responses are unexpected. If family members do not anticipate their own or patients’ responses, they are likely unequipped to cope with such responses. Without effective coping skills, family members’ psychological symptoms may go unaddressed and lead to health problems.34 Moreover, care partner and patient mental health is interdependent, meaning that care partners’ mental health influences patients’ mental health and vice versa.35 Adaptive coping skills such as problem-focused coping strategies may constitute a worthwhile intervention target to prepare families for ESKD treatments given their associations with positive psychological outcomes and capacity to offset negative linkages in the family member–patient dyad.36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Interventions targeting the transmission of negative emotions and psychological distress in the family member–patient dyad may be especially promising given their potential to improve psychological well-being among family members and patients alike.

Findings also raise questions about whether family members’ unexpected negative treatment experiences were unexpected for patients as well. The transfer of treatment information from patients to family members represents another means through which family members can prepare for treatment experiences. Despite a lack of attention to treatment information sharing between patients with ESKD and their family members, research in other illness populations has shown that patients who feel more able to share information about their illness with family members report better quality of life.44 Additionally, both patients’ and care partners’ perceptions of the extent to which their family avoids talking about illness affects their own mental health and quality of life.45 Therefore, ESKD treatment-related information sharing and communication within families may be a fruitful avenue for future research and intervention.

Limitations of this study deserve mention. First, data collection occurred several years ago. Given that ESKD treatments have not drastically changed in the past decade, there is little reason to believe that the data presented here are outdated. Second, the sample comprised family members of patients recruited from 1 geographic area, which could limit the generalizability of the results. Third, patients identified 1 family member for study participation. Family members not identified for participation might have contributed different insights. Notwithstanding these limitations, this study constitutes an initial step toward filling an important gap in the literature by describing family members’ unexpected negative experiences with different ESKD treatments. The findings reported here lay the groundwork for future research in this area and can guide the development of interventions to enhance care partner preparedness and improve the delivery of family-centered care.

In conclusion, family members of dialysis and posttransplantation patients described a broad range of unexpected negative experiences with ESKD treatments. Efforts to prepare families for ESKD treatments through additional research, more family-centered care, early and tailored education, and interventions targeting care partner preparedness, preparedness-focused communication between health care providers and patients’ family members, and relationship dynamics in the family member–patient dyad are needed.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Nicole DePasquale, PhD, Ashley Cabacungan, BS, Patti L. Ephraim, MPH, LaPricia Lewis-Boyér, CCRP, Neil R. Powe, MD, and L. Ebony Boulware, MD.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: PLE, NRP, LEB; data acquisition: PLE, LL-B; data analysis/interpretation: ND, AC, PLE, NRP, LEB; supervision or mentorship: LEB. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

Grant number R01 DK079682 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Drs Powe and Boulware). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, reporting, or the decision to submit for publication.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of this study.

Peer Review

Received March 27, 2019. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form June 9, 2019.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Item S1: Focus group question guide

Supplementary Material

Item S1

References

- 1.Hoang V.L., Green T., Bonner A. Informal caregivers’ experiences of caring for people receiving dialysis: a mixed-methods systematic review. J Ren Care. 2018;44(2):82–95. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y.C., Chang L.C., Liu C.Y., Ho Y.F., Weng S.C., Tsai T.I. The roles of social support and health literacy in self-management among patients with chronic kidney disease. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2018;50(3):265–275. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flythe J.E., Hilbert J., Kshirsagar A.V., Gilet C.A. Psychosocial factors and 30-day hospital readmission among individuals receiving maintenance dialysis: a prospective study. Am J Nephrol. 2017;45(5):400–408. doi: 10.1159/000470917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerogianni G., Babatsikou F., Polikandrioti M., Grapsa E. Management of anxiety and depression in haemodialysis patients: the role of non-pharmacological methods. Int Urol Nephrol. 2019;51(1):113–118. doi: 10.1007/s11255-018-2022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim K., Kang G.W., Woo J. The quality of life of hemodialysis patients is affected not only by medical but also psychosocial factors: a canonical correlation study. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(14):e111. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Untas A., Thumma J., Rascle N. The associations of social support and other psychosocial factors with mortality and quality of life in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(1):142–152. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02340310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mashayekhi F., Pilevarzadeh M., Rafati F. The assessment of caregiver burden in caregivers of hemodialysis patients. Mater Sociomed. 2015;27(5):333–336. doi: 10.5455/msm.2015.27.333-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebadi A., Sajadi S.A., Moradian S.T., Akbari R. Suspended life pattern: a qualitative study on personal life among family caregivers of hemodialysis patients in Iran. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2018;38(4):225–232. doi: 10.1177/0272684X18773763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oyegbile Y.O., Brysiewicz P. Family caregiver's experiences of providing care to patients with end-stage renal disease in South-West Nigeria. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(17-18):2624–2632. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabiei L., Eslami A.A., Abedi H., Masoudi R., Sharifirad G.R. Caring in an atmosphere of uncertainty: perspectives and experiences of caregivers of peoples undergoing haemodialysis in Iran. Scand J Caring Sci. 2016;30(3):594–601. doi: 10.1111/scs.12283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santos P.R., de Sales Santos I.M., de Freitas Filho J.L.A. Emotion-oriented coping increases the risk of depression among caregivers of end-stage renal disease patients undergoing hemodialysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2017;49(9):1667–1672. doi: 10.1007/s11255-017-1621-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alnazly E.K., Samara N.A. The burdens on caregivers of patients above 65 years old receiving hemodialysis: a qualitative study. Health Care Curr Rev. 2014;2(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nygardh A., Wikby K., Malm D., Ahlstrom G. Empowerment in outpatient care for patients with chronic kidney disease - from the family member's perspective. BMC Nurs. 2011;10:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-10-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Hare A.M., Song M.K., Kurella Tamura M., Moss A.H. Research priorities for palliative care for older adults with advanced chronic kidney disease. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(5):453–460. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welch J.L., Thomas-Hawkins C., Bakas T. Needs, concerns, strategies, and advice of daily home hemodialysis caregivers. Clin Nurs Res. 2014;23(6):644–663. doi: 10.1177/1054773813495407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farquhar M., Penfold C., Benson J. Six key topics informal carers of patients with breathlessness in advanced disease want to learn about and why: MRC phase I study to inform an educational intervention. PLoS One. 2017;12(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujinami R., Sun V., Zachariah F., Uman G., Grant M., Ferrell B. Family caregivers' distress levels related to quality of life, burden, and preparedness. Psychooncology. 2015;24(1):54–62. doi: 10.1002/pon.3562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henriksson A., Arestedt K. Exploring factors and caregiver outcomes associated with feelings of preparedness for caregiving in family caregivers in palliative care: a correlational, cross-sectional study. Palliat Med. 2013;27(7):639–646. doi: 10.1177/0269216313486954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magasi S., Buono S., Yancy C.W., Ramirez R.D., Grady K.L. Preparedness and mutuality affect quality of life for patients with mechanical circulatory support and their caregivers. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(1) doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petruzzo A., Biagioli V., Durante A. Influence of preparedness on anxiety, depression, and quality of life in caregivers of heart failure patients: testing a model of path analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(5):1021–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ephraim P.L., Powe N.R., Rabb H. The providing resources to enhance African American patients' readiness to make decisions about kidney disease (PREPARED) study: protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-13-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DePasquale N., Ephraim P.L., Ameling J. Selecting renal replacement therapies: what do African American and non-African American patients and their families think others should know? A mixed methods study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganji S., Ephraim P.L., Ameling J.M., Purnell T.S., Lewis-Boyer L.L., Boulware L.E. Concerns regarding the financial aspects of kidney transplantation: perspectives of pre-transplant patients and their family members. Clin Transplant. 2014;28(10):1121–1130. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheu J., Ephraim P.L., Powe N.R. African American and non-African American patients' and families' decision making about renal replacement therapies. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(7):997–1006. doi: 10.1177/1049732312443427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gielen A.C., McDonald E.M. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2002. Using the precede-proceed planning model to apply health behavior theories; pp. 409–436. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urquhart-Secord R., Craig J.C., Hemmelgarn B. Patient and caregiver priorities for outcomes in hemodialysis: an international nominal group technique study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(3):444–454. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morton R.L., Tong A., Webster A.C., Snelling P., Howard K. Characteristics of dialysis important to patients and family caregivers: a mixed methods approach. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(12):4038–4046. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong A., Manns B., Hemmelgarn B. Establishing core outcome domains in hemodialysis: report of the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Hemodialysis (SONG-HD) consensus workshop. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(1):97–107. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griva K., Li Z.H., Lai A.Y., Choong M.C., Foo M.W. Perspectives of patients, families, and health care professionals on decision-making about dialysis modality--the good, the bad, and the misunderstandings! Perit Dial Int. 2013;33(3):280–289. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2011.00308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zolfaghari M., Asgari P., Bahramnezhad F., AhmadiRad S., Haghani H. Comparison of two educational methods (family-centered and patient-centered) on hemodialysis: related complications. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2015;20(1):87–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker R.C., Hanson C.S., Palmer S.C. Patient and caregiver perspectives on home hemodialysis: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(3):451–463. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Washington K.T., Parker Oliver D., Smith J.B., McCrae C.S., Balchandani S.M., Demiris G. Sleep problems, anxiety, and global self-rated health among hospice family caregivers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(2):244–249. doi: 10.1177/1049909117703643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kershaw T., Ellis K.R., Yoon H., Schafenacker A., Katapodi M., Northouse L. The interdependence of advanced cancer patients' and their family caregivers' mental health, physical health, and self-efficacy over time. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(6):901–911. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9743-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marguerite S., Laurent B., Marine A. Actor-partner interdependence analysis in depressed patient-caregiver dyads: influence of emotional intelligence and coping strategies on anxiety and depression. Psychiatry Res. 2017;258:396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harmell A.L., Chattillion E.A., Roepke S.K., Mausbach B.T. A review of the psychobiology of dementia caregiving: a focus on resilience factors. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(3):219–224. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0187-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pessotti C.F., Fonseca L.C., Tedrus G.M., Laloni D.T. Family caregivers of elderly with dementia: relationship between religiosity, resilience, quality of life and burden. Dement Neuropsychol. 2018;12(4):408–414. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642018dn12-040011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pankrath A.L., Weissflog G., Mehnert A. The relation between dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction in couples dealing with haematological cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2016;27(1):e12595. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen H.M., Huang M.F., Yeh Y.C., Huang W.H., Chen C.S. Effectiveness of coping strategies intervention on caregiver burden among caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2015;15(1):20–25. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maslakpak M.H., Torabi M., Radfar M., Alinejad V. The effect of psycho-educational intervention on the caregiver burden among caregivers of hemodialysis patients. J Res Dev Nurs Midwifery. 2019;16(1):14–25. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilhooly K.J., Gilhooly M.L.M., Sullivan M.P. A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):106. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fu F., Zhao H., Tong F., Chi I. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions to cancer caregivers. Front Psychol. 2017;8:834. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lai C., Borrelli B., Ciurluini P., Aceto P. Sharing information about cancer with one's family is associated with improved quality of life. Psychooncology. 2017;26(10):1569–1575. doi: 10.1002/pon.4334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shin D.W., Shin J., Kim S.Y. Family avoidance of communication about cancer: a dyadic examination. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;48(1):384–392. doi: 10.4143/crt.2014.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Item S1