Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a home-based kidney replacement therapy used by a growing number of patients with kidney failure. This qualitative study explores the impact of remote management technologies on PD treatment priorities of patients, their care partners, and clinicians.

Study Design

Qualitative study, designed and conducted in collaboration with a stakeholder panel that included patients, patient advocates, care partners, and health care professionals.

Setting & Participants

13 health care providers, 13 patients, and 4 care partners with at least 3 months experience with PD were recruited from the United States and United Kingdom through postings in PD clinics, websites, and social media.

Methodology

Semi-structured telephone interviews with a purposive sample of participants.

Analytical Approach

Inductive thematic development adapted from a grounded theory approach through analysis of interview transcripts by 3 independent coders.

Results

4 main themes about PD treatments emerged that enabled evaluation of remote management: (1) impact of PD on everyday life, (2) simplifying treatment processes, (3) awareness and visibility of at-home treatments, and (4) support for managing treatments. The relative importance of these themes differed between patients/care partners and health care providers and by use of remote management cyclers.

Limitations

Remote management is new to PD, mirrored in the limited penetration of use in the study sample, suggestive of findings reflecting early adoption.

Conclusions

Participants welcomed technological advances such as remote management for PD, although priorities differed by stakeholder group. Remote management could potentially influence health care provider decisions about patient suitability for PD, while patients/care partners prioritized pre-emptive and early treatment adjustments. Currently, decisions about access to remote management are outside the control of patients and families, but this may change with more widespread use.

Index Words: Peritoneal dialysis, remote management, qualitative, patient-centered reporting

Editorial, p. 327

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a home-based treatment option for patients with kidney failure. Despite similar clinical outcomes,1, 2, 3 PD is used by only ∼10% of the more than 500,000 US patients receiving dialysis,4 while 89% receive their treatment at hemodialysis centers. In the United Kingdom, 13% of the more than 26,000 patients receiving dialysis use PD.4 The benefits of autonomy and flexibility offered by PD are countered by the increased burden of self-care that falls on the patient and/or his or her personal care partners. This shift in responsibility contributes to patient and health care provider concerns about an individual’s suitability for home therapy.5 Advancements that reduce the perceived risk for complications may encourage nephrologists to offer the choice of PD to a greater proportion of patients requiring dialysis.

The 2016 outline of an ideal telemedicine platform for PD included rapid communication to help troubleshoot problems.6 New remote management technologies achieve this by collecting PD treatment data (such as treatment time, lost dwell, drain, fill and dwell times, and ultrafiltration volume) from individuals at home and transmitting it securely to their health care provider. These data can facilitate increased health care provider awareness and provide the potential for better support through more frequent patient-clinician communication or clinical troubleshooting without the need for a clinic visit.6

This qualitative study explored the comparative viewpoints of patients, care partners, and health care providers to understand perceptions of how remote management meets PD treatment priorities, supports patients, and factors that might influence uptake.

Methods

The study was conducted in the United States and United Kingdom, 2 primarily English-speaking countries with variations in remote management use, health policies, and health governance structures. All study procedures were approved by central and/or local institutional review boards (E&I IRB00007807).

Stakeholder Panel

We first formed a 9-member stakeholder panel of individuals with PD experience: a nephrologist, PD nurses, a renal dietitian, renal social workers, and PD patients, all located in Michigan (United States). Members were directly involved in the research process through in-person meetings, teleconferencing, and e-mail collaboration. They actively engaged in discussions with 4 key informant clinical teams (2 each from the United States and United Kingdom) who had experience using remote management for PD. Members’ input informed protocol development, recruitment materials, data analysis, and interpretation. This input expanded researchers’ limited perspective of remote management and PD, improving the relevance and quality of interview data. Members received an honorarium for their participation.

Study Design

Our methodology included individual semi-structured telephone interviews that enabled us to engage participants from across the United States and United Kingdom. Interviews focused on PD and remote management while allowing participants to share individual perspectives and stories.7,8 Interview content was developed from key informant discussions, pilot testing and input from the stakeholder panel, and an established behavioral framework.9 To enable comparison, interview guides were similar across participant groups with some questions specific to each group. Topics included description of PD clinics, training for cycler use, patient experience with PD treatment and its impact, comfort in use of electronic technology, desired support, and view of remote management. The interviewers briefly explained current remote management technology for participants who were not familiar with it (Item S1).

Recruitment of Participants and Data Collection

Inclusion criteria were: (1) adults 18 years or older, (2) minimum 3 months of experience with PD, and (3) ability to speak and understand English. In the United States, patients, care partners, and health care providers were recruited through 6 PD clinics that distributed recruitment information, e-newsletters, and social media. In the United Kingdom, due to time constraints related to regulatory approvals, we were only able to interview health care providers recruited through PD clinics participating in the Peritoneal Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Pattern Study (PDOPPS). Interested participants were invited to contact the study team by telephone. After screening for inclusion criteria and obtaining verbal informed consent, demographic information was collected. We used a purposive sampling methodology to ensure that interviewees were diverse in demographics, age, patient residence (eg, rural or urban), clinical expertise, US or UK location, and with and without remote management experience. Participants were offered a $25 gift card on completion of interviews.

Interviews were conducted between September 2017 and January 2018 by 2 experienced interviewers (1 man and 1 woman). Interviews lasted 30 to 60 minutes and were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim. To ensure sufficiency and broad representation of perspectives, participant recruitment continued until researchers agreed that no new relevant knowledge was being obtained (data saturation).10

Analysis

Three interdisciplinary researchers/coders (L.S., R.K., and T.C.) contributed varied experience and professional training in clinical and social science, and quantitative and qualitative research. Data were initially examined using an adapted grounded theory approach.11,12 Coders completed independent selective, inductive coding of transcripts, using results to explore the relative importance of PD and remote management features. This allowed an understanding of varied perceptions between key stakeholder groups—patients, care partners, and health care providers—and those with and without personal remote management experience. Through the review and coding process, researchers iteratively developed and used a shared coding framework that identified emergent themes and subthemes that were then used to develop theory related to remote management use and its impact on patient care and health outcomes. Patients and care partners were collapsed into a single group during analysis due to similarity and lack of divergence in priority and themes.

Data were organized, shared, and managed using NVivo 11 software and amended through discussion. NVivo also enabled comparisons to check coding reliability. Themes and subthemes were ranked by frequency of coding; the full range of responses was retained to ensure a comprehensive description.

This process, the results, and preliminary theory were shared with the stakeholder panel in lieu of member checking13; members assisted in the selection of illustrative quotes and confirmed researchers’ interpretations. Direct quotes were used to illustrate key points, strengthen credibility, and preserve subjective viewpoint. This analytical plan supported our efforts to maximize the validity and trustworthiness of these data.

Results

Study Participants

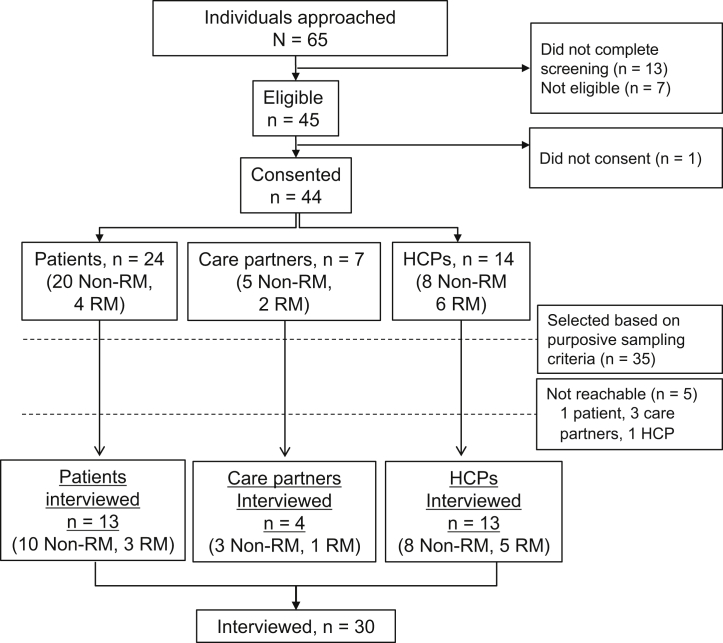

Sixty-five potential participants responded to our recruitment efforts (Fig 1); 22 through US and UK PD clinics, 27 through social media outreach, and 16 from indirect sources. Of these, 44 (67.7%) consented to participate. Based on purposive sampling criteria, 35 (88%) participants were selected (Table 1) and 30 were successfully interviewed (27 US and 3 UK residents). Patients and care partners were diverse in sex, remote management use, living situation, education, occupation, race, ethnicity, and travel factors associated with clinic visits. The 13 health care provider interview participants included 7 (53.8%) PD nurses, 5 (38.5%) nephrologists, and 1 (7.7%) other PD support professional. Ten health care providers practiced in the United States, and 3 in the United Kingdom; 5 health care providers had remote management experience and 8 did not.

Figure 1.

Interview participant screening and purposive sampling. A total of 65 potential participants responded to recruitment efforts; based on screening, eligibility, consent, and purposive sampling, 30 were interviewed. Abbreviations: HCPs, health care providers; non-RM, not remote management user; RM, remote management user.

Table 1.

Summary of Demographic Information Collected From Participants

| Patients (n = 13) | Care Partners (n = 4) | Patients & Care Partners (n = 17) | Health Care Providers (n = 13) | All (N = 30) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean PD experience, years | 3.1 (0-7) | 3 (1-5) | 13.9 (1-32) | ||

| Mean age, years | 50.0 (24-80) | 44 (36-55) | 48.6 (24-80) | 46.9 (33-65) | 47.8 (24-80) |

| Locationa | |||||

| Urban | 46% | 0% | 35% | 85% | 57% |

| Rural | 39% | 25% | 35% | 62% | 47% |

| Suburban | 15% | 75% | 29% | 69% | 47% |

| Sex | |||||

| Women | 69% | 75% | 71% | 62% | 67% |

| Remote management use | |||||

| Yes | 23% | 25% | 24% | 39% | 30% |

| Living situation | |||||

| Live alone | 46% | ||||

| Live with others | 54% | ||||

| Education | |||||

| High school/GED | 23% | 0.0% | 18% | ||

| Some college | 46% | 25% | 41% | ||

| ≥4-year degree | 31% | 75% | 41% | ||

| Occupationb,c | |||||

| Full-time work | 23% | 50% | 29% | ||

| Part-time work | 23% | 0% | 18% | ||

| Student | 8% b | 0% | 6% | ||

| Unemployed | 23% | 25% | 24% | ||

| Homemaker | 0% | 50% c | 12% | ||

| Other (retired, disabled) | 31% | 25% | 29% | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 15% | 0% | 12% | 8% | 10% |

| Non-Hispanic | 85% | 100% | 88% | 92% | 90% |

| Race | |||||

| White | 31% | 50% | 35% | 77% | 53% |

| Black | 39% | 25% | 35% | 0% | 20% |

| Asian | 8% | 0% | 6% | 8% | 7% |

| Pacific Islander | 8% | 0% | 6% | 0% | 3% |

| Native American | 0% | 25% | 6% | 0% | 3% |

| Other | 0% | 0% | 0% | 8% | 3% |

| Transport to PD clinic visit | |||||

| Patient drives | 85% | ||||

| Family/friend/care partner drives | 15% | ||||

Note: All percentages were rounded to whole numbers. Values expressed as mean (range) or percent.

Abbreviations: GED, general educational development; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Location referred to the location of their patients and as such yielded multiple responses from most health care providers.

One patient was engaged in full-time work and a student.

Multiple care partners were both homemakers and had other occupational status.

Major Themes and Subthemes

Four major interrelated themes about PD treatment and remote management emerged from interviews: (1) impact of PD on everyday life, (2) simplifying treatment processes, (3) awareness and visibility of at-home treatments, and (4) support for managing treatments. The relative importance of these themes and their related subthemes differed depending on the participant group (patient and care partner or health care provider) and whether they had direct experience with using remote management cyclers.

Theme 1: Impact of PD on Everyday Life

Participants identified a wide range of interrelated impacts of PD treatment on their activities, work, and social life. These either demonstrated the intrusiveness of PD or PD treatment management (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of Subthemes and Illustrative Quotes for Impact of PD on Everyday Life Theme

| Subtheme | Content | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Intrusion of PD | ||

| Space and weight of cyclers and supplies | Bags and PD cyclers are heavy to move and difficult to carry and take up a lot of storage room. | “Those bags, yeah they’re very, very heavy… if I carry them a bad way, when I lay down the lower part of my back will hurt.” Patient 319 (57 y-old female patient who lives alone, RM user) |

| Obtrusive cycler noise | The noise of the machine was rarely mentioned but mattered to some participants. | “It would be nice if it was quieter, that’s my biggest issue is if it had somewhere to sit that maybe absorbed some of the vibration so it would be quieter at night. I wear ear plugs.” Care partner 534 (45-y-old female care partner who assists with spouse, non-RM user) |

| Patient Autonomy and Confidence | ||

| PD affects patients' feelings of self-confidence and limits abilities to do some things. The availability, sensitivity, and nature of support matters. | “I mean I was very independent, I went on all these. .. trips by myself and now, I have to have somebody with me, and fortunately this son is self-employed and he’s enjoyed the trips a lot so, he’s been able to go with me, but if he weren’t able to go, I probably wouldn’t be able to go.” Patient 525 (79-y-old female patient who lives alone, non-RM user) | |

| Management of PD Treatment | ||

| Determining patient suitability for PD at home | Factors identified by many HCPs included home environmental factors, personal attitudes, abilities, motivation, and the distance between home and the clinic. A few HCPs factored in effect of RM on treatment adherence while a few HCPs without RM experience considered availability of informal support. | “We do home visits with all the patients to make sure there’s…not a lot of clutter, not a lot of dirt, make sure that they’re able to do their treatments and that there’s no risk of infection. So we do that at least once a year.” HCP 680 (33-y-old female PD nurse, RM user) “So it’s more about what makes this family or home environment not make home therapies work… but actually they’re generally the big questions of `which home therapy would we consider?’ not `why would we consider home therapy?’ it takes a lot for us to rule a home therapy out.” HCP 269 (41-y-old female pediatric nurse from the UK, RM user) |

| Expense and time related to treatment | Additional costs related to travel to clinic, storage space, or time required for dialysis were mentioned by some participants. | “...we can do things for them remotely without them having to actually come in, it’s wonderful….and I guess for the most part I think they would like it because now they don’t have to make the trip in” HCP 505 (63-y-old female nephrologist, RM user) |

| Workload and related systems | Patients and care partners described changes to employment and domestic responsibilities in accommodating PD while HCPs talked about the flexibility needed in their work to meet patient and PD needs. Overall there was an impression that RM might reduce workload for patients/care partners and save time and improve existing systems for HCPs. | “I think there would be a lot of little pieces that would add up to save time management and running around that could be better spent on education and other more important pieces.” HCP 163 (42-y-old female nurse, non-RM user) |

| Drainage of PD solution | A few participants mentioned the impact of pain after drainage, which may affect treatment adherence, so an ability to control the drainage step was desired. | “The problem is, for when it first starts, there’s a drain cycle, and you can’t bypass it…and, for me, it was one of the most excruciatingly painful things “…Patient 575 (24-y-old male patient, non-RM user) |

| Individualization of treatment | HCPs tailor PD treatment in response to individual variations in laboratory tests, changes in weight and blood pressure, and patient perspectives. Generally, because RM rapidly provides the patient and clinic staff with detailed treatment data, individual profiles and treatment can be made more quickly. | “You find out what the problem is for that patient…do they hate the fact that their thirst is driven so much by the strong bags, and is that why they’re non-adherent sometimes? And then you try and address that by maybe optimizing their drains or do they hate …that they’re getting so many alarms overnight, and that’s why they’re non-adherent, so then instead you address the alarm parameters, but you put a different measure in place to make them safe in the morning. So it’s about, if you have that time to invest and to really get to understand each individual patient, then you can make a huge difference.” Nurse 269 (41-y-old female nurse, RM user) |

| Patient Travel and Outings | ||

| A major impact of PD on patients and their close family concerns the constraints treatment has on their ability to spontaneously travel and participate in outings; HCPs are very concerned about this too and make a lot of effort to minimize this. | “I want them to experience life and not let dialysis interfere with their lifestyle, so we bend over backward…, just so they can travel” HCP 505 (63-y-old female nephrologist, RM user) “He’s not able to really go to things in the evenings. I still participate … with the kids or church activities or…any that might conflict with him setting up his treatment, so it’s limited. Care partner 511 (40-y-old female care partner who assists with spouse, RM user) |

|

Abbreviations: HCP, health care provider; PD, peritoneal dialysis; RM, remote management.

Regardless of remote management experience, patients and care partners indicated that PD significantly affects their lives and that remote management is unlikely to address all of these impacts. They most frequently remarked on the subtheme “patient travel and outings” as an aspect of their lives most affected by PD. They elaborated on the necessity for additional planning, time, and cost to have PD supplies delivered to a travel destination. Some highlighted restrictions associated with the length of overnight PD exchanges that required them to be home early to start treatment. Several also mentioned the weight of the cycler.

“I had to make sure I had enough bags and then take the cycler in with me. It would probably be easier if they were smaller and make it easier to travel with ‘cause they collect it and just sent my bag to where I’m going but the cycler is heavy.” (Patient, non–remote management user)

Participants who used remote management remarked on the benefits of equipment size and portability.

“I like the idea this new machine is smaller. I can carry it if I need to…it’s more convenient.” (Patient, remote management user)

In contrast, most health care providers prioritized the impact of remote management on PD treatments, particularly relating to patient suitability for PD care.

“I think we do select for people who have a stable home environment, somebody who is interested in self-care—obviously, they have to be motivated—and who we think would benefit from PD. …we’re sort of looking for…somebody who can take care of themselves.” (Nephrologist, non–remote management user)

However, not all health care providers agreed, and 1 nephrologist noted that PD candidate selection is challenging.

“What I think we’ve shown, over and over again, is that our judgment of who’s a good candidate or not is really poor.” (Nephrologist, remote management user)

Theme 2: Simplifying PD Processes

Subthemes related to the desire for simplicity in operating the cycler, managing supplies, training, and for fewer monitoring tasks all coalesced under this theme (Table 3). Most interviewees believed that PD training was comprehensive and adequate to support independent treatments at home and welcomed format choice. Concerns were related to the length of setup and dialysis time, the weight of supplies, and challenges associated with moving bags from storage to the bedside cycler. Recording vitals (eg, blood pressure and weight) as part of daily treatments figured prominently for both participant groups. Traditionally, patients manually record their vitals on paper before and after each PD treatment and bring these to clinic visits. However, patients identified a potential benefit in the remote management–assisted recording of vitals and sharing with health care providers.

“It just seems that we use a lot of paper doing the things and then you have to remember to take them with you…it would be kind of official and less time wasted [if] he [the nephrologist] could already look at it….” (Patient, non–remote management user)

Table 3.

Summary of Subthemes and Illustrative Quotes for Simplifying Treatment Processes Theme

| Subtheme | Content | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Easier Use | ||

| User-friendly setup and instruction | Patients described the experience of treatment setup as time consuming and requiring a number of steps. Recommendations included that cyclers be easier to use, eg, step-by-step guidance, more user-friendly operational buttons, tubing extensions that enable increased patient mobility, and that mobile apps could be developed to assist; Optional format choice was welcomed with a touch screen and/or voice control. Cleaning or infection concerns were not mentioned by any patients. | “It tells me when my treatment is going to be over, which is really good, I never knew with the other machine, it doesn’t say, you know because it didn’t talk and it didn’t have, it wasn’t hooked to the internet.” Patient 319 (57-y-old female patient who lives alone, RM user) “The voice would be better cause my vision is blurred. For people who can’t see that well, the voice is better” Patient 319 (57-y-old female patient who lives alone, RM user) |

| Simplify Management of Supplies | ||

| Ordering and delivery | Patients generally described the process of ordering and receiving supplies as simple and user friendly. Some referenced challenges in moving heavy bags while others mentioned reminders from clinic staff to order. However, frequent changes in prescriptions for treatment may have cost implications for the patient. | “If they don’t place their order by a certain time, then they’re contacted …to remind them, and if they still don’t place the order then (the manufacturer) contacts our clinic to say, ‘these people haven’t yet placed their order.’ So then I contact them, and remind them, or ask them if they need any help…and go from there, but, every 2 weeks they’re either placing their order or receiving their order.” HCP 119 (57-y-old female nurse, non-RM user) |

| Training for PD | ||

| The training provided to RM and non-RM users was viewed positively and as appropriate. It varied from one site to another and often included trial runs with cyclers at home and in the hospital under close clinical supervision and support, home visits, training of an informal supporter etc. All stressed the importance of making sure patients were comfortable and confident with the treatment. | “It usually takes you know 3 to 5 days to do that, it’s usually conducted largely in the patient’s home although it can be also done here in the hospital. And in terms of proficiency, they do an oral test, they don’t do a written exam, at the end of their training.” HCP 155 (63-y-old male nephrologist, non-RM user) “I think they did a good job cause well when I first started I did the manuals first and I wasn’t sure about the cycler …it was by my nurse from the clinic. I thought she did a really good job…They do go over a lot of stuff when I go twice a month to the clinic and so they still go over things with me to make sure I’m still doing it right.” Patient 517 (45-y-old female patient, non-RM user) |

|

| Fewer Things for Patients to Do | ||

| Recording vitals (eg, blood pressure, weight as part of daily treatments) | Recording vitals was the most frequently discussed item by HCPs (both RM and non-RM) and non-RM patients and caregivers. The daily recording of vitals is generally viewed as a small burden to patients that could be alleviated through electronic RM recording, however, not all RM systems have implemented this feature and some patients liked manual recording to preserve some treatment control or engagement. | “It just seems that we use a lot of paper doing the things and then you have to remember to take them with you…it would be kind of official and less time wasted [if] he [the nephrologist] could already look at it, you know.” Patient 532 (47-y-old female patient without RM) “…I would still like to retain some kind of control over taking my blood pressure and my weight every day. Other than that, if they can just take the rest of the data that would be wonderful.” Patient 796 (53-y-old female patient without RM) |

Abbreviations: HCP, health care provider; PD, peritoneal dialysis; RM, remote management.

Manual recording of vitals was viewed by some patients as benefiting treatment engagement and control. When asked about having treatment information transmitted daily to the clinic, a patient said:

“…I would still like to retain some kind of control over taking my blood pressure and my weight every day. Other than that, if they can just take the rest of the data that would be wonderful.” (Patient, non–remote management user)

Some health care providers expressed concerns about the reliability of monthly paper-based records and viewed remote management as increasing reliability and treatment compliance.

“I see if they’re putting in their vital signs, so I believe it’s more strict in this way because you’re going to see everything, you’re going to see their vital signs, you’re going to see their weight, you’re going to see how their treatment went.” (Nurse, remote management user)

However, a pediatric PD nurse in the United Kingdom emphasized the importance of recording vitals to engage families in patient care:

“…I think it would be important…that the family is still doing monitoring to some degree, too…even if they’re not so responsible for the documentation, but they’re another point of checking the information.” (Nurse, non–remote management user)

Theme 3: Awareness and Visibility of At-Home Treatments

Three subthemes emerged related to improving awareness and visibility of PD treatment data (Table 4). The new opportunity to view data was most frequently discussed; participants mentioned actual or potential benefits of treatment data being instantly visible by clinicians. Some thought it encouraged adherence with the treatment regimen, enhanced communication about treatment changes, or facilitated faster treatment change to reach optimization.

Table 4.

Summary of Subthemes and Illustrative Quotes for Awareness and Visibility of At-Home Treatments Theme

| Subtheme | Content | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid treatment change | HCPs indicated that RM enabled quicker intervention, including rapid and responsive changes to treatment (especially for new PD patients and those who live far away from the clinic). Patients and care partners thought that RM would be beneficial to HCPs to enable speedier checks on treatment, address related issues, and be more prepared for in-person visits. It was also noted that if patient information was not recorded (or not recorded properly), RM would still capture this accurately. One care partner described a concern that if treatment data are transmitted every day, their doctor may want to fix or change things daily, which could be burdensome. | “So to have the nurse just key in a few strokes and change it, and then we say `okay try it, if it works fine, it’s not then we just change it again.’ I think it’s just one of the best things I’ve seen in technology in a long time, is the ability to change the prescription remotely.” HCP 505 (63-y-old female nephrologist, RM user) “I feel that they could…just maybe look on the computer and see, daily, how they’re doing with the treatment…it would help the patient a lot, because I know…for me, I don’t like to have to keep going into the clinic 2, 3 times a week…ya know, I got stuff I’d rather be doing” Patient 786 (36-y-old female patient, non-RM user) |

| Treatment choice | While not discussed by the majority of HCPs, 2 indicated that it would be desirable to have an option to adjust PD treatment settings, such as having 2 or 3 treatment programs that a patient could choose from. Patients and care partners did not discuss treatment choice. | “I could program 2 prescriptions, prescription ‘A’ for the days he goes out and prescription ‘B’ for the days he stays home, and he picks and chooses which one works for him that day and he uses it, which is really wonderful.” HCP 505 (63-y-old female nephrologist, RM user) “Sometimes I have people travelling and they want to sight see, that’s the reason why they’re on a trip and they don’t want to do that day exchange, or … instead of being on the machine for 9 hours, they want 6 hours. For a day or 2 it’s not going to change their dialysis that much so you can give them a third prescription for when they’re travelling, so all these things can be done remotely. I’m all in favor for the remote adjustment of the prescriptions.” HCP 505 (63-y-old female nephrologist, RM user) |

| Visibility | Some patients and care partners and HCPs liked the idea of having access to information quickly for various reasons, including adherence, fast treatment change, and ease of monitoring. They also thought it could be more convenient for communicating changes without waiting for a clinic visit, thus optimizing treatment. However, a few thought that constant visibility of instant records could potentially lead to over management. | “I think if they could already look at the data and kind of know, you know `well she’s having a lot of lost dwell time’ and `we can change this and we can change that’, I think it would be better.” Patient 532 (47-y-old female patient, non-RM user) “They would have all the information before I got to the office…and if they did see any issues, they could call me instantly and have me go in…” Patient 538 (50-y-old female patient, non-RM user) |

Abbreviations: HCP, health care provider; PD, peritoneal dialysis; RM, remote management.

A participant with 13 years of PD experience envisaged 1 potential convenience:

“…because if they maybe notice something with the numbers that doesn’t look too right, I won’t have to wait to come in or…they can just call me and maybe have me go up on the solution or go down… and do it all through phone, so yeah it would be more convenient.” (Patient, non–remote management user)

However, a few patients and care partners were concerned about increased visibility leading to micromanaging and more clinic visits:

“I think it would be easy enough to maybe transmit monthly but daily I just think that would be overkill and I already feel like you know they micro manage us and I guess…it defeats the whole purpose of being autonomous…” (Care partner, parent, non–remote management user)

Most health care providers spoke positively about the benefits of visibility, particularly the improved treatment and patient experience that could result from remote management’s potential for rapid treatment change.

Theme 4: Support for Managing Treatments

Two treatment support subthemes emerged (Table 5); formal support from professionals, including health care providers, and informal support from family, friends, and acquaintances.

Table 5.

Summary of Subthemes and Illustrative Quotes for Support for Managing Treatments Theme

| Subtheme | Content | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Formal support | ||

| Formal support was most frequently talked about by participants who described who provided it, how it was achieved, whether it was available, if it could be improved, and how often help was provided. Details are given below: Source: health and allied professionals, includes nurses, nephrologists, community nurses (UK), social workers, financial advisers, etc Type: Type of support ranged from the very specific to general and was mainly medical and/or practical (eg, interpretation of laboratory results, treatment change, training, troubleshooting), advice & information (PD related), social and/or emotional (eg, clinic attendance) Method: Formal support was provided primarily by telephone. Other methods of formal support referenced at much lower frequency included in-person, e-mail, telemedicine, Skype, and home visits Frequency: Frequent (as required; daily, weekly, etc) indirect contact by telephone etc. Direct contact through clinic visits; periodic (usually monthly in the US) |

“…I run a sort of a telephone…outreach clinic service. Some patients come less frequently now…We can stretch maybe to 6 or 8 weekly with one of my virtual clinics, telemedicine clinics, half way through, because of having Sharesource’s ability. “ HCP 505 (63-y-old female nephrologist, RM user) “Our patients call when they have issues…I handle what I can over the phone, if I can’t then they come and see me in clinic that week, we just schedule…” HCP 574 (37-y-old male nephrologist, non-RM user) |

|

| Informal support | ||

| Informal support or help was often provided by family, friends, and occasionally by delivery people and neighbors who helped deliver and move PD supplies. Some patients were apparently independent and fairly self-sufficient with managing PD at home and did not use or want any support from family or friends. Reciprocity is a component of the concept of support. Details are given below: Source: Family (mostly) and friends Type: Support was often a combination of types including emotional (eg, talking about health concerns, accompanying patient during clinic visits), practical (eg, helping lift supplies, travel companion), and to a lesser extent medical support (eg, performance of specific medical PD tasks) Method: Mainly in-person individual or group although telephone and on-line support groups were noted. Care partners rarely talked of their own support Frequency: As required for most patients, although there were a few who had no informal support and managed okay, but it could be an isolating experience Reciprocity: Some patients mentioned that they wanted to give support (eg, by educating other patients) as well as receive it |

“…one of my sons has been willing to go with me…we’ve had 4 or 5 flights…and he manages the equipment, and talks to the airlines about putting it in a closet so that it doesn’t have to be thrown into the luggage; and he helps me set it up when we get there; it’s allowed me to still be as active.” 525 Patient (79-y-old female patient who lives alone, non-RM user) “…the idea of having that support you know that makes me cry because I’ve been doing it on my own and by myself and …the reality is …I don’t have that and I never did have that and …it just made me a little emotional because I never had it.” Patient 319 (57-y-old female patient who lives alone, RM user) “We have a good family structure and they help you out…I won’t say it’s easy but it makes it a lot easier doing things.” Patient 344 (46-y-old male patient who lives with partner and children, non-RM user) “We set up a local support group for just the dialysis and transplant moms from our hospital…which is a nice place to vent or to laugh, get information about our hospital specifically … and those moms are the best support group, because they understand exactly what it’s like… I’ve also, with our social worker for the ‘on dialysis patients’… I’ve let them know like when new moms are facing this stuff, that I’m available, and so a lot of times the social worker will refer other moms to me, so I can like, talk to them and kind of help them… and being able to help other people in this situation, is very rewarding for me, ya know, cause I’ve been through a lot of the different aspects of the kidney disease… so it’s been nice to be able to help other people” Patient 698 (36-y-old female care partner to a pediatric patient, non-RM user) |

|

Abbreviations: HCP, health care provider; PD, peritoneal dialysis; RM, remote management.

Formal support was most frequently discussed by all participants; the various sources, types, frequency, and wide availability of support provided by professionals. Both groups described formal supports provided by health care providers to patients as being effective in enhancing treatment regardless of communication mechanism (in-person, by telephone, home visit, e-mail, or telemedicine). Services included troubleshooting, treatment management, reminders to order supplies, training, preparation and provision of manuals and treatment folders, assisting with travel arrangements, interpretation of laboratory results, and home visiting. These services were provided by nurses, nephrologists, community nurses (United Kingdom), social workers, and dieticians. Formal support was described as available to patients at all times, primarily by telephone or during clinic visits.

A care partner thought it would be worthwhile for future remote management platforms to enable texting as a communication mechanism with health care provider teams. Some patients and care partners welcomed clinical staff more regularly monitoring their treatment records and consequently being more proactive with treatment adjustments.

“Compared to before, I would have to wait until I get in there with my record sheets for them to see what’s going on.” (Patient, remote management user)

The frequency of support varied based on need, preference, availability, clinic, and insurance coverage. Some health care providers believed the desired effect of remote management support was to reduce the frequency of clinic visits for patients. However, some nephrologists believed that further evolution of remote management technology would be needed to allow this.

“So what I would love to see, but I don’t know if it’s ever going to happen, is to be able to do a remote monthly visit with the patients so they don’t have to come to the dialysis unit…we could do a video chat…and I would be in the office, and say `okay here are your labs, and how’s everything going?’ The technology is not there.” (Nephrologist, remote management user)

Although most patients visit a clinic monthly, recent developments may be changing this pattern. An experienced nurse in the United Kingdom who uses remote management said:

“I run a sort of a telephone…outreach clinic service—some patients come less frequently now… instead of coming 4 weekly, we can stretch maybe to 6 or 8 weekly with one of my virtual clinics, telemedicine clinic’s, halfway through, because of having [remote management] ability.” (Nurse, remote management user)

The availability and use of informal support from family, friends, and acquaintances was deemed important but less often discussed in interviews. For many patients, informal support was necessary to enable them to fulfill many of their previous activities and new ones required by PD.

Discussion

The 4 major themes that emerged in this study—impact of PD on everyday life, simplifying treatment processes, awareness and visibility of at-home treatments, and support for managing treatments—provide insight into the priorities that remote management does and does not address for patients, their care partners, and health care providers. Of note, participants welcomed technological advances such as remote management for PD, although priorities differed by stakeholder group.

PD offers potential benefits of greater treatment-related flexibility, reduced travel to dialysis, patient autonomy, and comparable or better clinical outcomes than in-center hemodialysis.2,14, 15, 16 Despite these advantages, PD is underused in some countries, including the United States and United Kingdom.17 Quality of life is clearly important to dialysis patients; in a time-tradeoff study, patients and family members were willing to forgo months of life expectancy in exchange for home dialysis and ease of travel.18 Thus, technologies and interventions that improve quality of life for dialysis patients are of primary importance.

The introduction of new health care technology frequently results in a range of direct and indirect impacts. Involving stakeholders in decision making during development and implementation promotes inclusiveness, transparency, and the participation of those for whom clinical practice changes have a substantial consequence.19 Our qualitative investigation is among the first such studies of remote management for PD treatment. It evoked valuable details of benefits and drawbacks, potentially assisting in the refinements necessary to mature this technology. Its strengths lie in input from a diverse stakeholder panel and the uncommon breadth obtained from sampling 3 different stakeholder perspectives. Both remote management and non–remote management users brought their experiences and opinions to this conversation. The information collected and transmitted by remote management is similar to what patients using non–remote management cyclers collect and record on a daily basis. Thus, it was not difficult for nonusers to understand what remote management provides and to speculate on what would make it even more useful.

Consistent with prior literature, patients and care partners expressed challenges with current PD technology, including the time required for treatment, managing supplies, and the social and personal impacts of PD.20 Despite the perceived benefits of remote management in recording and transmitting treatment data and the potential for more responsive treatment adjustments, this group did not view it as fully alleviating daily treatment burdens.

Patients and care partners in our study viewed both formal and informal support as important components of their PD treatment, as others have shown regarding health in general.21 Advances in remote management technology may enhance these supports. Perceptions of the perceived benefits of remote management reported in this study may herald changes to the nature, quantity, and availability of PD support.

Our results suggest that health care providers tend to view remote management as a tool with the potential to significantly change the management and delivery of PD care, consistent with other studies evaluating clinical changes based on availability of remote data.22 Patients and care partners perceived the visibility of treatment data as an opportunity for rapid identification of clinical issues. However, the associated concerns about micromanagement impinging on patient autonomy suggest that elements of individual tailoring may be helpful when implementing remote management, with greater support provided to new PD patients and shared decision making regarding the level of oversight.6 Less evidence is available on remote management changing the need for or type of informal support.

There are many barriers to home dialysis therapy, including health care provider concerns about patient competence and suitability for complex self-care.23 Based on our results, concerns are variably defined and often based on clinician judgment. This is supported by literature suggesting that dialysis modality decision making and access to PD in the United States is primarily led by nephrologist preferences.5,24, 25, 26 Remote management holds the potential to reduce health care provider concerns of treatment completion and concordance, thereby increasing PD use.7,27, 28, 29 Results suggest that programs seeking to expand home dialysis30 begin with an assumption of patient suitability, offering shared treatment decision making and tailored support in using a home modality, rather than starting with the assumption of nonsuitability.

Remote management, including telehealth, has been used to improve patient outcomes in other serious chronic diseases. Remote management has shown some benefit in reducing hospital admission rates and mortality in congestive heart failure.31 Similarly, it may be an effective intervention for improving glycemic control in diabetes.32 Whether it can improve patient experience and outcomes in PD has yet to be demonstrated. Remote management may also reduce some of the barriers to PD use. This will be better understood when larger groups of patients and providers gain experience with remote management and direct qualitative and quantitative comparisons can be made. The benefits we identified are encouraging and indicate that remote management may enable PD for some patients formerly considered to be poor candidates.

This qualitative study reflects early adoption of remote management for PD and has certain limitations. At the time of recruitment, remote management was not yet widely deployed, so users were difficult to find and tended to have less experience with remote management–enabled cyclers. Participants using remote management tended to be new to PD or cycler therapy, which may have affected the themes that emerged in their interviews. Additionally, enrolled participants were younger than typical dialysis patients, and purposive sampling was used to minimize this limitation by widening the age range of those selected for interviews. Although there was great similarity in remote management topics related by participants with and without direct remote management experience, those with experience were able to provide more detail and nuanced discussion on the new PD cyclers. Stakeholder perspectives in the United Kingdom were limited to health care providers, and future studies are planned to obtain patient and care partner self-reports internationally. By restricting to English-speaking participants and recruiting primarily using written materials, this study did not explore barriers to home dialysis therapy related to language and literacy.

Future activities stemming from this study include the development and deployment of surveys focused specifically on remote management, through the international PDOPPS, enabling longitudinal assessment of remote management impact. We will also investigate associations between remote management and clinical outcomes such as peritonitis and technique failure.

In its introductory state, remote management may more clearly meet the needs and interests of health care providers than patients and care partners. Future research, improved clinical practice offering tailored patient support, shared decision making about access, and technology development are needed to advance opportunities for remote management to improve patient quality of life by decreasing the challenges of disease and treatment.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Lalita Subramanian, PhD, Rosalind Kirk, PhD, Tony Cuttitta, MPH, Nicole Bryant, Kimberly Fox, BA, Margie McCall, BA, Erica Perry, LMSW, June Swartz, MA, Yanko Restovic, Allison Jeter, MS, Angelito Bernardo, MD, Bruce Robinson, MD, Jeffrey Perl, MD, Ronald Pisoni, PhD, and Rachel L. Perlman, MD.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: LS, TC, RK, JS, MM, RP, BMR, AB, RLP; data acquisition: LS, TC, BMR, KF, RLP; data analysis/interpretation: LS, TC, RK, EP, AJ, MM, RP, BMR, AB, JP, KF, RLP; statistical analysis: LS, TC; supervision or mentorship: LS, RK, MM, NB, RP, YR, BMR, AB, RLP. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

Part of this work has been supported by specific funding from Baxter Healthcare. Global support for the ongoing DOPPS and PDOPPS programs is provided without restriction on publications. See https://www.dopps.org/AboutUs/Support.aspx for more information.

Financial Disclosure

Dr Bernardo is an employee of Baxter. Dr Perlman was employed by both the University of Michigan and Arbor Research Collaborative for Health at the time of her work on this report. Dr Robinson, Mr Cuttitta, Dr Pisoni, and Ms Fox are employees of Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, which administers the DOPPS and PDOPPS programs. Dr Perl has received consulting fees and speakers honoraria from Fresenius Medical Care and has received speaker fees from Baxter Healthcare, Fresenius Medical Care and Davita Healthcare, Satellite Healthcare, and Dialysis Clinics Inc; research support from Baxter Healthcare; and salary support from Arbor Research Collaborative for Health. The remaining authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgements

Janet Leslie and Jennifer McCready-Maynes, employees of Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, provided technical writing and editing assistance, respectively.

Peer Review

Received June 10, 2019. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form July 28, 2019.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Item S1: Interview guides for care partners, health care providers, and patients.

Supplementary Material

Item S1.

References

- 1.Weinhandl E.D., Foley R.N., Gilbertson D.T., Arneson T.J., Snyder J.J., Collins A.J. Propensity-matched mortality comparison of incident hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(3):499–506. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009060635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar V.A., Sidell M.A., Jones J.P., Vonesh E.F. Survival of propensity matched incident peritoneal and hemodialysis patients in a United States health care system. Kidney Int. 2014;86(5):1016–1022. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeates K., Zhu N., Vonesh E., Trpeski L., Blake P., Fenton S. Hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis are associated with similar outcomes for end-stage renal disease treatment in Canada. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(9):3568–3575. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Renal Data System . National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2017. USRDS 2017 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahlerus C., Quinn M., Messersmith E. Patient perspectives on the choice of dialysis modality: results from the Empowering Patients on Choices for Renal Replacement Therapy (EPOCH-RRT) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(6):901–910. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallace E.L., Rosner M.H., Alscher M.D. Remote patient management for home dialysis patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2(6):1009–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontana A, Frey J. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials, London: Sage Publication; 2003:61-106.

- 8.Rabionet S.E. How I learned to design and conduct semi-structured interviews: an ongoing and continuous journey. Qual Rep. 2011;16(2):563–566. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michie S., Van Stralen M.M., West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willig C. McGraw-Hill Education; Berkshire, UK: 2013. Introducing Qualitative Research in Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charmaz K. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulawa P. Adapting grounded theory in qualitative research: reflections from personal experience. Int Res Educ. 2014;2(1):145–168. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubin H.R., Fink N.E., Plantinga L.C., Sadler J.H., Kliger A.S., Powe N.R. Patient ratings of dialysis care with peritoneal dialysis vs hemodialysis. JAMA. 2004;291(6):697–703. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.6.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehrotra R., Chiu Y.-W., Kalantar-Zadeh K., Bargman J., Vonesh E. Similar outcomes with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(2):110–118. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lameire N., Van Biesen W. Epidemiology of peritoneal dialysis: a story of believers and nonbelievers. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6(2):75–82. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiwakanon S., Chiu Y.-W., Kalantar-Zadeh K., Mehrotra R. Peritoneal dialysis: an underutilized modality. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010;19(6):573–577. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32833d67a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morton R.L., Snelling P., Webster A.C. Dialysis modality preference of patients with CKD and family caregivers: a discrete-choice study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(1):102–111. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Culyer A.J. Involving stakeholders in health care decisions–the experience of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in England and Wales. Healthc Q. 2005;8(3):54–58. doi: 10.12927/hcq..17155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong A., Lesmana B., Johnson D.W., Wong G., Campbell D., Craig J.C. The perspectives of adults living with peritoneal dialysis: thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(6):873–888. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen S., Syme S.L. Issues in the study and application of social support. Soc Support Ad Health. 1985;3:3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallar P., Vigil A., Rodriguez I. Two-year experience with telemedicine in the follow-up of patients in home peritoneal dialysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13(6):288–292. doi: 10.1258/135763307781644906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charest A.F., Mendelssohn D.C. Are North American nephrologists biased against peritoneal dialysis? Perit Dial Int. 2001;21(4):335–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song M.-K., Lin F.-C., Gilet C.A., Arnold R.M., Bridgman J.C., Ward S.E. Patient perspectives on informed decision-making surrounding dialysis initiation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(11):2815–2823. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keeney S., McKenna H. An exploration of the choices of patients with chronic kidney disease. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:1465-1474. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S60766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansson L. Shared decision making and patient involvement in choosing home therapies. J Ren Care. 2013;39:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2013.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosner M.H., Lew S.Q., Conway P. Perspectives from the Kidney Health Initiative on advancing technologies to facilitate remote monitoring of patient self-care in RRT. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(11):1900–1909. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12781216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rygh E., Arild E., Johnsen E., Rumpsfeld M. Choosing to live with home dialysis-patients' experiences and potential for telemedicine support: a qualitative study. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-13-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanabria M., Bunch A., Aldana F. Trends in outcomes for an automated peritoneal dialysis program with and without remote management in Colombia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;1(33):52–61. [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Maar J.S., de Groot M.A., Luik P.T., Mui K.W., Hagen E.C. GUIDE, a structured pre-dialysis programme that increases the use of home dialysis. NDT Plus. 2016;9(6):826–832. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfw037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin M.H., Yuan W.L., Huang T.C., Zhang H.F., Mai J.T., Wang J.F. Clinical effectiveness of telemedicine for chronic heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Investig Med. 2017;65(5):899–911. doi: 10.1136/jim-2016-000199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee P.A., Greenfield G., Pappas Y. The impact of telehealth remote patient monitoring on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):495. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3274-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Item S1.