Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Community house hemodialysis is a submodality of home hemodialysis that enables patients to perform hemodialysis independent of nursing or medical supervision in a shared house. This study describes the perspectives and experiences of patients using community house hemodialysis in New Zealand to explore ways this dialysis modality may support the wider delivery of independent hemodialysis care.

Study Design

Qualitative semi-structured in-depth interview study.

Setting & Participants

25 patients who had experienced community house hemodialysis. Participants were asked about why they chose community house hemodialysis and their experiences and perspectives of this.

Analytical Approach

Thematic analysis using an inductive approach.

Results

25 patients were interviewed (14 men and 11 women, aged 31-65 years). Most were of Māori or Pacific ethnicity and in part- or full-time employment. More than two-thirds dialyzed for 20 hours a week or more. We identified 4 themes that described patients’ experiences and perspectives of choosing and using community house hemodialysis: reducing burden on family (when home is not an option, minimizing family exposure to dialysis, maintaining privacy and self-identity, reducing the costs of home hemodialysis, and gaining a reprieve from home), offering flexibility and freedom (having a normal life, maintaining employment, and facilitating travel), control of my health (building independence and self-efficacy, a place of wellness, avoiding institutionalization, and creating a culture of extended-hour dialysis), and community support (building social inclusion and supporting peers).

Limitations

Non-Māori and non-Pacific patient experiences of community house hemodialysis could not be explored.

Conclusions

Community house hemodialysis is a dialysis modality that overcomes many of the socioeconomic barriers to home hemodialysis, is socially and culturally acceptable to Māori and Pacific people, and supports extended-hour hemodialysis and thereby promotes more equitable access to best practice services. It is therefore a significant addition to independent hemodialysis options available for patients.

Index Words: End-stage kidney disease, home hemodialysis, patient preference, decision-making, semi-structured interviews

Editorial, p. 321

There is global inequity in access to home hemodialysis for indigenous peoples in New Zealand and Australia1,2 and Canada3 and for minority populations in the United States.4 Home hemodialysis is associated with markedly improved survival, quality of life, and life participation and incurs lower personal and health system treatment costs compared with facility-based hemodialysis.5, 6, 7, 8 For patients who are unable to or are waiting to receive a kidney transplant, extended hours of home hemodialysis is associated with clinical and quality-of-life outcomes that are closer to transplantation than other dialysis modalities.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

Despite these potential advantages, many health systems lack home hemodialysis provision or expertise. In addition, many patients may not access home hemodialysis because of patient-related factors that include insufficient access to appropriate accommodation, patient and caregiver concerns about dialyzing independently, social isolation, burden on family members, and the intrusion of dialysis in the home.15

Community house hemodialysis enables patients to perform hemodialysis in an unstaffed community home-like setting. Community house hemodialysis is an approach to providing independent hemodialysis located within or close to a patient’s community. In Australia, community house hemodialysis was developed to support access to hemodialysis closer to home in remote and very remote regions.16, 17, 18 In New Zealand, the first community hemodialysis houses were set up to support patients from both urban centers and remote areas for whom inadequate housing and/or utilities were barriers to home hemodialysis.19 Our previous research has indicated that Māori and Pacific patients choose home dialysis to maintain a sense of individual and cultural identity and sustain involvement in community, cultural, and, for Pacific people, religious responsibilities.20

In a previous analysis of the population served by community house hemodialysis in New Zealand, the majority of patients identified as Māori and Pacific. Patients using community house hemodialysis were younger and had fewer comorbid conditions than those using all other hemodialysis modalities.19 It was also found that those using community house hemodialysis had similar reported quality-of-life outcomes compared with patients using conventional home hemodialysis.19,21

This study aims to describe the perspectives and experiences of patients using community house hemodialysis to understand how and why community house hemodialysis is used and the experienced advantages and disadvantages of this treatment modality. This will help identify ways that community house hemodialysis may address inequity in access to home-based dialysis therapies and increase the use of independent hemodialysis modalities.

Methods

This study is reported according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ).22

Setting

Four community hemodialysis houses are used in New Zealand. The community house program was initiated by a collaboration between dialysis service providers and patient support groups.19 Patients have their own designated machine in the houses, although some machines are shared between 2 patients. Some rooms within the houses have multiple machines, which enables patients to maintain social contact and peer support by scheduling dialysis treatments with a “buddy.” The houses are maintained by the patients and the patient support group, have televisions and heating in each room, and have a kitchen accessible to patients, families, and visitors.19 Further information and photographs of the community hemodialysis houses are available in Item S1.

Participant Recruitment and Selection

Potential participants were recruited through the Auckland District Kidney Society, a nonprofit patient organization, and the Hawke’s Bay renal service (a public dialysis provider including provision of community house hemodialysis). Potential participants were patients who had used community house hemodialysis to perform independent hemodialysis. In Auckland, the Auckland District Kidney Society invited all patients who were currently using or had previously used the community hemodialysis houses to participate. In Hawke’s Bay, all patients who had experienced community hemodialysis were identified by staff members at the home dialysis training unit and invited to participate in the study.

Patient recruitment and interviews occurred during September and October 2018. Of the 30 identified patients, 25 agreed to participate and were consented and interviewed. Five patients declined due to other commitments. The study was approved by the Hawke’s Bay District Health Board Ethics Committee (18/06/296) and was identified as out of scope for national ethics approval.

Data Collection

Participants chose their interview location. The interview guide included questions about the patient’s choice of hemodialysis location; the reasons for choosing to do dialysis at a community hemodialysis house, including specific exploration of social, cultural, and economic reasons; and the experienced advantages and disadvantages of the community house dialysis (Item S1).

Two authors conducted the interviews (R.C.W. and A.G.). More than half the interviews were conducted by the 2 authors together (to ensure consistency of interviewing) and 12 were conducted by either interviewer. Both authors are female clinicians with a PhD and experienced in qualitative interviewing techniques. One interviewer (A.G.) identifies as being of both Māori and Pacific ethnicity. The other interviewer (R.C.W.) is a nephrology nurse practitioner. Interpreters and cultural support workers were offered to all participants but were not requested. One interviewer (R.C.W.) was known to 4 of the participants.

Theoretical data saturation was achieved after 18 interviews were conducted. Further interviews were conducted to ensure diversity of age, sex, and ethnicity. Interview length varied from 23 to 49 minutes. Field notes were taken during each interview. Member checking of transcripts and review of draft themes was offered to participants to allow review and revision of the interpretation of findings. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were entered into the software program HyperRESEARCH, version 3.7.2 (ResearchWare Inc), to manage qualitative data. Thematic analysis was used to identify patterns and themes within the interview data.23 R.C.W. coded the transcripts line by line, identified concepts inductively, and grouped similar concepts specific to patient experiences and perceptions of community house dialysis. A.G. also independently identified concepts inductively and grouped similar concepts together. The preliminary thematic framework was reviewed by all authors. In subsequent iterations, the coding schema was refined through a series of discussions between all authors.

Results

Twenty-five participants (age range, 31-65 years), including 14 men and 11 women, were interviewed (Table 1). Ten self-identified as Māori and the others self-identified as being of Pacific Island ethnicity, including 1 participant identifying as Fijian of Indian descent. Fifteen reported having vocational or university qualifications and 14 were in part- or full-time employment. Eighteen had previously experienced facility hemodialysis; 5, peritoneal dialysis; and 2, kidney transplantation. Eighteen participants dialyzed more than 20 hours per week. Twenty-three participants were interviewed while receiving dialysis and 2 were interviewed in a private clinic room.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age category | |

| 31-40 y | 7 (28%) |

| 41-50 y | 9 (36%) |

| 51-60 y | 6 (24%) |

| 61-65 y | 3 (12%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married/de facto | 11 (44%) |

| Partner (not living together) | 3 (12%) |

| Divorced/separated | 1 (4%) |

| Single | 8 (32%) |

| Widowed | 2 (8%) |

| Highest level education | |

| Some secondary | 2 (8%) |

| Completed secondary | 8 (32%) |

| Trade certificate or equivalent | 6 (24%) |

| Completed certificate or diploma | 2 (8%) |

| Completed degree | 5 (20%) |

| Postgraduate education | 2 (8%) |

| Employment status | |

| Fulltime | 6 (24%) |

| Part-time | 8 (32%) |

| Beneficiary | 10 (40%) |

| Retired | 1 (4%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Māori | 10 (40%) |

| Tongan | 3 (12%) |

| Samoan | 7 (28%) |

| Cook Island Maori | 4 (16%) |

| Fijian Indian | 1 (4%) |

| Time to closest dialysis unit (traveled 1 way) | |

| 0-10 km | 16 (64%) |

| 11-50 km | 4 (16%) |

| 51-100 km | 2 (8%) |

| >101 km | 3 (12%) |

| Cause of kidney disease (self-identified) | |

| Diabetes | 10 (40%) |

| Hypertension | 1 (4%) |

| IgA nephropathy | 3 (12%) |

| Nephrotoxic medication | 1 (4%) |

| Vasculitis | 1 (4%) |

| PKD | 1 (4%) |

| Unsure | 8 (32%) |

| Length of time on dialysis | |

| 0-2 y | 7 (28%) |

| 3-4 y | 5 (20%) |

| 5-6 y | 5 (20%) |

| 7-8 y | 5 (20%) |

| 9-10 y | 0 (0%) |

| <10 y | 3 (12%) |

| Hours on dialysis | |

| 15 h/wk | 4 (16%) |

| 18 h/wk | 3 (12%) |

| 20 h/wk | 12 (48%) |

| 20-25 h/wk | 4 (16%) |

| <26 h/wk | 2 (8%) |

| Previous RRT modalitya | |

| Facility HD | 18 (72%) |

| PD | 5 (20%) |

| Home HD | 2 (8%) |

| Transplantation | 2 (8%) |

| Time to closest CHH (traveled 1 way) | |

| 0-10 km | 17 (68%) |

| 11-50 km | 6 (24%) |

| 51-100 km | 2 (8%) |

| >101 km | 0 (0%) |

Abbreviations: CHH, community home hemodialysis; HD, hemodialysis; IgA, immunoglobulin A; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PKD, polycystic kidney disease; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

Some participants had experienced more than one previous RRT modality.

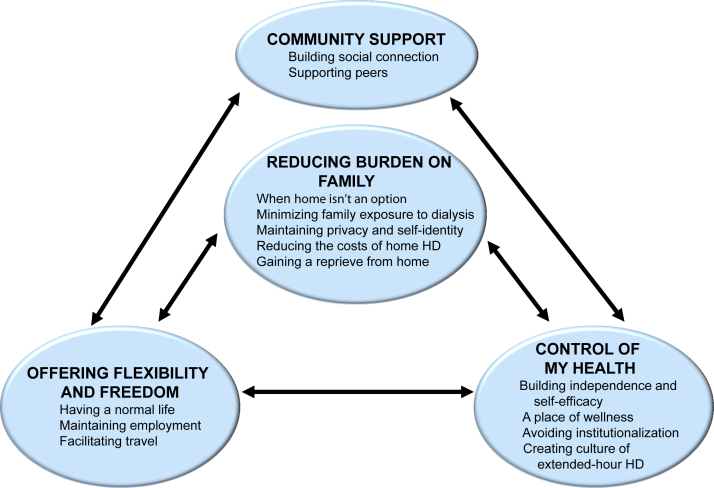

Four themes were identified that described patients’ experiences and perspectives of choosing and using community house hemodialysis: reducing burden on family, offering flexibility and freedom, control of my health, and community support (Fig 1). Selected participant quotations are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Thematic schema of connections between themes. Community house hemodialysis (HD) offers flexibility and freedom to patients by allowing them to participate in daily activities, maintain employment, and travel. This in turn makes patients feel in control of their own health by encouraging independence and self-efficacy. Community house HD is considered a place of wellness that allows patients to avoid institutionalization and promotes a culture of extended-hour dialysis. By facilitating a home away from home, community house HD reduces the burden on family and patient and allows patients to maintain privacy and self-identity while also reducing the costs of home hemodialysis. Community house HD also improves the support patients receive from their dialysis peers.

Table 2.

Selected Participant Quotes of Patient Experiences of Community House Hemodialysis

| Subtheme | Representative Quotations |

|---|---|

| Reducing burden on family | |

| When home is not an option | “It would be good if I could get a machine in my house, but a lot of people can’t, so the community house is the better option if you can’t do it at home, it’s your home away from home” (Man, 40s) “I got a 2 bedroom house, but a lot of people, and not a lot of room for my bed, and stuff and it wasn’t good enough to put the machine, not enough room for machine and storage. The houses have more space” (Woman, 50s) “There wasn’t room at our house. Not at my house at my grandma and my sister a 2 bedroom house” (Man, 30s) |

| Minimizing family exposure to dialysis | “Keeping this part separate from the rest of the family, which is I think that is a really good benefit is that you keep, you are still independent, so you get some, but you are still able to do this part this kidney treatment part separate from the rest of your home” (Woman, 30s) “We have just recently bought our house and I do not want to give up being here. Being at home I don’t want to put [my wife] through this” (Man, 30s) “I don’t know if I’d feel safe enough with needles and stuff around with grandchildren around, so it is safer for my grandchildren for me to be here and probably better for me too” (Woman, 50s) |

| Maintaining privacy and self-identity | “You come and do your thing and then you can go home. And that’s one of the reasons why a lot of pacific Island people do that and they want to keep that separation” (Woman, 30s) “Home is just home, I can keep them separate” (Woman, 40s) “But better than home, quieter you can lock yourself in your room do your dialysis and be left alone” (Woman, 50s) |

| Reducing the costs of home | “I think it’s cheaper coming here with the heating, definitely I prefer here to home, there’s no heater at home at all, cause we can’t afford one, so this is better and warmer for dialysis, I'd freeze at home” (Woman, 50s) “I know one patient she had it at home and it started leaking and flooded her whole house out, it ruined all of her carpets and everything (Man, 40s) |

| Getting a reprieve from home | “But in some ways better than home, quieter, you can lock yourself in your room, do your dialysis and be left alone” (Woman, 50s) “I get 5 hours of peace and you have some downtime. I suppose that is another benefit here, you get time for yourself, compulsory downtime and that does actually help” (Man, 40s) “At that time I had my sister living with me and I needed time out so this is my haven, my time out” (Woman, 50s) “Sometimes I come here to escape” (Man, 30s) |

| Offering flexibility and freedom | |

| Having a normal life | “Being able to come whenever you feel like it instead of having to fit into the hospital routine. I come whenever it suits me. Those reasons make dialysis a lot more doable and liveable and part of your life as opposed to attending your dialysis appointment. It make it feel like it is just one section of your life rather than the hospital taking over your life” (Woman, 40s) “My kids and what they have on if I want, so that’s massive, being able to live a life, come in early in the morning or late at night, to fit in with my lifestyle and actually have a life, that makes a huge difference to your family” (Woman, 50s) |

| Maintaining employment |

“I was going to work Monday to Friday full time and not only that, I have access so if I don’t feel well, I can come and dialyse, just open up the door and it’s like I am in my room” (Man, 40s) “This house provides you that opportunity to work, to own and run my own successful business” (Man, 60s) “If they are working, you can still work, come to the house and go home” (Woman, 30s) “I wanted to do my own dialysis instead of having to go into the hospital because I wanted to work” (Woman, 30s) |

| Facilitating travel | “It’s really good to have holidays, the way the houses work if there was more houses then more people could go on more holidays and see their family” (Woman, 50s) “If they had a community house up there it would be better I could actually get home, do what I need to do for my whānau” (Man, 60s) “I wouldn’t move anywhere where there isn’t a community house, the only downfall is that there isn’t more, you know everywhere in the country and overseas” (Woman, 40s) |

| Control of my health | |

| Building independence and self-efficacy | “More independence and more control” (Woman, 30s) “If I know I’m overloaded I dialyse in the community house, this stops me going to ED so often” (Woman, 50s) “I think that sense of independence with a lot of people here that really helps them. They have some control, they feel as if they have some control over their life which is good for them and for me as well I like that” (Man, 30s) |

| A place of wellness | “It’s better than the hospital, cause there aren’t sick people, at the hospital you see sick patients, since I went to the community house I feel more confident there, and everyone is well, you feel well there” (Woman, 50s) “I come here and do this and I leave it here and then I get home and it’s like I am still me, I am not this disease or just this treatment, that’s not what I am all about, cause I leave it here” (Woman, 50s) “It is part of life, it is not my life” (Woman, 30s) |

| Avoiding institutionalization | “I was dialysing at the clinic and that is so busy there it is like a traffic jam of people. There are 12-15 machines in one room and you are like sardines” (Woman, 40s) “here you are relaxed with no pressure on you nothing none of that. Whereas in the hospital you feel pressured to get yourself in and out” (Man, 40s) “If they have got people dialysing at the houses it means that they don’t have to wait in line at the hospital” (Man, 60s) |

| Creating a culture of extended hours | “the more hours I do the more I feel better, so the houses allow me to do more hours, I couldn’t do at hospital and also, I can come in and do it” (Woman, 50s) “If we get overloaded we can just come in and take fluid off. I can come and use the machine when it is available. I do 4 days of 6½ hours. Some people do 8 hours (Man, 40s) “I was doing 20, but at the moment I am feeling better doing more, so I keep doing more, more energy” (Woman, 50s) |

| Community support | |

| Building social connection | “We are a community, a family in the houses, we aren’t strangers on dialysis, we are there to support each other, there are no barriers there” (Man, 40s) “I would prefer it in the community house, cause sometimes you can feel isolated at home, cause even though you’ve got whānau there, it’s not the same thing as someone else going through it too, you know they don’t understand, and that can make you feel isolated” (Woman, 50s) “Well the community house you get to know the people in the house too and its like your own family at the same time” (Man, 60s) “you don’t feel lonely here, there’s always people coming in and out, sometimes you can feel lonely on dialysis at home” (Woman, 50s) |

| Supporting peers | “If people are new, [I ask them] ‘Are you new? Do you want me to stand at the doorway?’ And then I go ‘How’s it going’ and I leave them on the machine, I will go get a coffee and their door is open if you panic and just sitting there, there will be people in the room who know exactly what it is like to do the first one by yourself and we all go ‘bro, I have been there before you’” (Man, 60s) “It’s good having your buddy there. So that’s how I helped this lady, cause she was saying that when she first started she cried and she was too scared to go into the community house and I said to her, ’Don’t panic, there’s no rush, you finish everything, there isn’t any hurry here, you look after your wellbeing’. We look after each other in the house” (Woman, 50s) |

Reducing Burden on Family

When Home Is Not an Option

Most participants stated that they had initially preferred home hemodialysis but could not access home-based care for reasons such as not owning their own home or not being permitted to install a machine in a rental property. “I don’t think my landlord would have liked it” (man, 40s). Some patients did not have enough space in their homes for a machine or storage of dialysis supplies, or they could not access adequate water supply. “The only option was move, or use the community house, so really the community house meant at that time I could stay at home, I didn’t need to relocate and uplift my family for my dialysis” (man, 40s). Many participants chose to continue with community house hemodialysis even when home dialysis became an option, describing the community house as “my home away from home” (woman, 30s).

Minimizing Family’s Exposure to Dialysis

Many participants chose to dialyze in a community house setting to protect their families from having “dialysis in their face” (man, 50s) at home. Participants considered that doing dialysis at home was too confronting to their family, especially for children, and wanted to “keep that part of your life separate” (man, 40s). In addition, many worried about the safety of their children if they had a dialysis machine and needles at home. Pacific families particularly reported that the views of family members about sickness, needles, and blood were an important consideration in their decision to not do dialysis in their own home. “My wife didn’t want it” (man, 50s).

Maintaining Privacy and Self-identity

Participants appreciated the privacy that community house hemodialysis offered compared to hospital or home. This modality provided them with dialysis away from family and friends “discreetly, and your whānau [family] does not need to know” (man, 40s). For some, this privacy allowed them to not have to discuss personal health issues with extended family or friends unless they chose to. Māori participants particularly perceived that home hemodialysis would be like “being on show” (man, 40s) and that it was a “cultural thing” (man, 60s) to not want to talk about their own health problems. Some participants also spoke of protecting their own self-identity as a parent by not allowing their children to see them as a “sick mum” (woman, 30s) on dialysis.

Reducing the Costs of Home Dialysis

Many participants were aware that community house hemodialysis reduced out-of-pocket costs such as power and water charges compared to home hemodialysis. They also saw the benefits of not having to pay for their own heating, especially during cooler months, and therefore appreciated that at the community houses, they could have a more comfortable dialysis environment than they could afford at home.

Gaining a Reprieve From Home

Participants described the community house as a sanctuary, particularly for those with children or who had many people living in the home. Both Māori and Pacific people described the houses as a place in which they could have “time for yourself, compulsory downtime” (man, 40s) that helped their mental and physical health. “It’s also good to get away from home sometimes and I think community houses are a great idea for people with busy lives, you know, kids at home” (woman, 50s).

Offering Flexibility and Freedom

Having a Normal Life

Community house hemodialysis enabled participants to maintain normal activities, which directly improved quality of life. For many who had experienced hospital dialysis, the community house provided better schedule flexibility with greater choices about treatment times and days for dialysis, as opposed to “letting the dialysis rule your life” (man, 40s). Participants could adjust their dialysis hours, times, and days to attend family, cultural, and religious commitments and priorities. “I can do the hours that I want and change these every treatment to suit my kids … being able to come in early in the morning or late at night, to fit in with my lifestyle and actually have a life, that makes a huge difference to your family, to your ability to work, I felt a lot better too” (woman, 50s).

Maintaining Employment

Flexibility of treatment scheduling of community house hemodialysis allowed patients to meet their work commitments, which also enabled patients to provide financially for their families. The community house hemodialysis model also ensured that patients could minimize career disruption and achieve employment progression and promotion while sustaining long-hours hemodialysis.

Facilitating Travel

Many participants described their desire to travel and valued being able to change their dialysis schedule to allow for a longer break to “go home” (man, 40s). This was very important for Pacific patients who wished to sustain connections with family and other commitments in the Pacific region and indigenous New Zealand patients (Māori) who wished to “go home when I need to go home, like when to tangi [funerals] and important hui [meetings]” (man, 40s). Participants spoke about a national and possibly international network of community houses as a way to facilitate holiday dialysis nationally and internationally.

Control of My Health

Building Independence and Self-efficacy

Community house hemodialysis was experienced as promoting “independence and more control” (man, 40s) of health and well-being. Participants identified their dialysis and health as being solely their responsibility when they moved to community house hemodialysis, rather than the responsibility of health professionals. They felt empowered to manage their dialysis hours and frequency to reduce symptoms and manage fluid control. They spoke of their sense of self-determination by choosing the hours and number of dialysis sessions they did and that “you had no-one to blame but yourself” (woman, 30s). They also saw the houses as stopping them from having to present to the hospital because they could do more dialysis when needed in response to clinical fluid overload, rather than having to wait until their next planned dialysis session.

A Place of Wellness

Most participants spoke of facility dialysis as a place of sickness. This contrasted with the community house hemodialysis, where “you wouldn’t even know most of us were even on dialysis” (woman, 30s). The psychological advantage of being away from “sick patients” (woman, 50s) or feeling like “a patient, lying down with a nurse doing the dialysis for me” (woman, 30s) was talked about by all patients as having a positive effect on their emotional and psychological well-being.

Participants spoke of not assuming a sick role and not feeling defined by their kidney disease when they dialyzed in community houses. “I come here and do this and I leave it here and then I get home and it’s like I am still me, I am not this disease or just this treatment, that’s not what I am all about, cause I leave it here” (woman, 50s). Māori patients actively encouraged other patients to dialyze in the community house, especially the “young people” (woman, 30s) to protect their “wairua [spirit]” (man, 50s).

Avoiding Institutionalization

Participants were aware of the increasing demand for dialysis services and the busyness of the facility dialysis units. They believed that people who were capable should be doing their dialysis independently and facility dialysis should be “saved for the old and really sick” (woman, 30s). Participants who had used facility dialysis discussed the overcrowding and feeling like they were on a “factory line” (woman, 50s) of dialysis. Participants felt in facility units that they were “treated as a number” (man, 40s) and spoke of their desire to avoid this.

Creating a Culture of Extended-Hour Dialysis

Most participants chose to do hemodialysis for more than 20 hours a week, after they were initially encouraged to by others in the community houses, confirming the advice of their nephrologist that extended-hour dialysis was beneficial. Participants discussed seeing other patients doing longer hours and that this was seen as normal and part of the culture within the dialysis houses. “I saw the others doing it, and heard them talking that they felt heaps better, and so I kept extending my hours, and the more hours I do the more I feel better, so the houses allow me to do more hours” (woman, 30s).

Participants also had identified themselves that the more hours they did the better they felt, “I was doing 20, but at the moment I am feeling better doing more, so I keep doing more, I’ve got more energy” (woman, 50s).

Community Support

Building Social Connection

Community house hemodialysis provided companionship that participants did not experience when they were receiving home hemodialysis. Some participants explained they had felt “isolated at home” (woman, 30s). This was particularly important for younger patients who did not want to dialyze alone but also feel they did not “fit in” (man, 50s) at facility hemodialysis. They spoke of wanting to dialyze with other people who they could relate to, “people who are like us” (man, 30s). Participants also reported that community house hemodialysis provided a “dialysis family” (woman, 50s) and community of support. The community houses also provided a mechanism to form friendships with others who were going through similar challenges. “I used to be a scared person, but this community house has opened me up, I am a better person now” (woman, 50s).

Supporting Peers

Community house hemodialysis enabled participants to support other patients who were also dialyzing at the houses. Many discussed the peer support they had received when they first started, how this reassured them and helped them progress to be independent with their dialysis. This was described as the “culture” (man, 60s) of the houses and how they in turn supported other new patients. “We look after each other in the house” (woman, 30s).

Some patients, who had experienced community house hemodialysis for longer, took the new patients under their wing and helped them, especially during the initial transition from training in which they realized that patients were especially anxious about doing their dialysis. Many described the benefit of talking with and learning from other patients, while some provided other patients with advice about their treatments because they had “a wealth of knowledge” (man, 40s).

Discussion

This study indicates that community house hemodialysis meets the treatment preferences of a group of patients who otherwise may not use home hemodialysis. It is found to be a highly acceptable independent hemodialysis modality for this group of predominantly Māori and Pacific patients, a group who typically have lower uptake of home dialysis. Community house hemodialysis also supports this group to achieve hemodialysis best practice by providing them with the physical resources to dialyze flexibly and choose extended hours. Accordingly, community house hemodialysis supports patient self-management, quality of life, and psychosocial support while providing a treatment that is adaptive to patient requirements for fluid management and social and community responsibilities. Enabling and providing hemodialysis modalities to facilitate extended-hour hemodialysis aligns with the evidentiary benefits of longer hours in respect to survival,24, 25, 26, 27 cardiac remodeling,28 and quality of life, particularly in kidney-specific domains.13,28,29

This study has identified a number of themes around community house hemodialysis that are similar to patients’ experiences of home hemodialysis, including freedom and flexibility, avoiding facility hemodialysis, and gaining independence, control of health, and self-efficacy.15,20,30 Additionally, we found that community house hemodialysis abrogates many of the barriers associated with choosing to do home hemodialysis. These include increased out-of-pocket dialysis costs,31,32 medicalizing the home,15,32 the wish to protect the family from the burden of dialysis,32,33 and loss of privacy and self-identity.30,33 The emotional burden of hemodialysis34 coupled with social isolation, which are central disadvantages of home hemodialysis,33,35,36 may be avoided with community house hemodialysis. A number of broader social and economic issues related to high-density living (eg, not having the space, not owning own home, and additional out-of-pocket expenses) and temporary or rental accommodation (eg, not being able to have a machine plumbed in) are also addressed by community house hemodialysis. Because patients living with high socioeconomic deprivation have a higher incidence of severe kidney disease and lower access to home dialysis,37,38 the community house benefits of reduced personal costs, ability to maintain employment, and space that provides a reprieve from home and allows for a dialysis machine may reduce some of the additional burden of dialysis on patients and families.

Community house hemodialysis is used in New Zealand nearly entirely by Māori and Pacific patients.19 This is likely because community-based dialysis specifically mitigates the adverse socioeconomic consequences of hemodialysis, including direct utility costs and loss of employment, while providing a culturally appropriate form of care that assists participants to maintain mana (control, pride, independence) alongside acceptance of an inclusive, socialized, and shared dialysis environment. These aspects directly address ethnicity-based inequity in access to home-based dialysis care and increase availability and use of self-management and peer support to achieve longer hours and frequent hemodialysis for Māori and Pacific patients.39 Participants in this study were not able to identify any disadvantages to dialyzing in the community hemodialysis houses. This also provides another avenue to further increase the use of non–facility-based dialysis, the more cost-effective option,40 and we recommend this be explored in future economic evaluations.

The strengths of this study include being able to procure interviews with Māori and Pacific participants who are traditionally difficult to engage in research41 and who in this case are representative of the population groups who do community house hemodialysis. Another strength was member checking of transcripts by participants. Participants were offered the opportunity to review both their transcripts and the final interpretation of findings. Although generalizability is not recognized as a limitation of qualitative studies, it could be postulated that New Zealand might be different from other health jurisdictions in that the specific experienced benefits of community house hemodialysis might be different in other health settings.

In conclusion, community house hemodialysis is a dialysis modality that overcomes many of the socioeconomic barriers to home hemodialysis, is socially and culturally acceptable to Māori and Pacific people, supports extended-hour hemodialysis, and thereby promotes more equitable access to best practice services. It is therefore a significant addition to independent hemodialysis options available for patients.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Rachael C. Walker, NP, PhD, David Tipene-Leach, MB ChB, FRNZCGP (Dist), FNZCPHM, Aria Graham, PhD, and Suetonia C. Palmer, MB ChB, PhD, FRACP.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: RCW, SP; data acquisition: RCW, AG; data analysis/interpretation: RCW, AG, SCP, DTL; Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. RCW takes responsibility that this study has been reported honestly, accurately, and transparently; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted, and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Support

This study was supported by a New Zealand Lotteries Health Research Grant. The funder did not have any role in the study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing the manuscript; or the decision to submit for publication.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who participated in this study and the Auckland Kidney Society for assistance with participant recruitment.

Peer Review

Received May 5, 2019. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form July 20, 2019.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Supplementary Material File (PDF)

Item S1: Details and background of community house hemodialysis

Supplementary Material

Item S1.

References

- 1.New Zealand National Renal Advisory Board . Ministry of Health; Wellington, New Zealand: 2018. New Zealand Nephrology Activity Report 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKercher C., Jose M.D., Grace B., Clayton P.A., Walter M. Gender differences in the dialysis treatment of indigenous and non-indigenous Australians. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2017;41(1):15–20. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trinh E., Na Y., Sood M.M., Chan C.T., Perl J. Racial differences in home dialysis utilization and outcomes in Canada. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(11):1841–1851. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03820417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehrotra R., Soohoo M., Rivara M.B. Racial and ethnic disparities in use of and outcomes with home dialysis in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(7):2123–2134. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015050472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansen K.L., Zhang R., Huang Y. Survival and hospitalization among patients using nocturnal and short daily compared to conventional hemodialysis: a USRDS study. Kidney Int. 2009;76(9):984–990. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall M.R., Hawley C.M., Kerr P.G. Home hemodialysis and mortality risk in Australian and New Zealand populations. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(5):782–793. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kjellstrand C.M., Buoncristiani U., Ting G. Short daily haemodialysis: survival in 415 patients treated for 1006 patient-years. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(10):3283–3289. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pauly R.P., Gill J.S., Rose C.L. Survival among nocturnal home haemodialysis patients compared to kidney transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(9):2915–2919. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kooistra M.P., Vos J., Koomans H.A., Vos P.F. Daily home haemodialysis in the Netherlands: effects on metabolic control, haemodynamics, and quality of life. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13(11):2853–2860. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.11.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McFarlane P.A., Pierratos A., Bayoumi A.M., Redelmeier D.A. Estimating preference scores in conventional and home nocturnal hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(3):477–483. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03941106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heidenheim A.P., Muirhead N., Moist L., Lindsay R.M. Patient quality of life on quotidian hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(1 suppl):36–41. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00536-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vos P.F., Zilch O., Jennekens-Schinkel A. Effect of short daily home haemodialysis on quality of life, cognitive functioning and the electroencephalogram. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(9):2529–2535. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Eps C.L., Jeffries J.K., Johnson D.W. Quality of life and alternate nightly nocturnal home hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2010;14(1):29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2009.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wyld M., Morton R.L., Hayen A., Howard K., Webster A.C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of utility-based quality of life in chronic kidney disease treatments. PLoS Med. 2012;9(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker R.C., Hanson C.S., Palmer S.C. Patient and caregiver perspectives on home hemodialysis: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(3):451–463. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marley J.V., Dent H.K., Wearne M. Haemodialysis outcomes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients of remote Kimberley region origin. Med J Aust. 2010;193(9):516–520. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb04035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kneipp E., Murray R., Warr K., Fitzclarence C., Wearne M., Maguire G. Bring me home: renal dialysis in the Kimberley. Nephrology. 2004;9(4 suppl):S121–S125. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2004.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villarba A., Warr K. Home haemodialysis in remote Australia. Nephrology. 2004;9(4 suppl):S134–S137. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2004.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall M.R., van der Schrieck N., Lilley D. Independent community house hemodialysis as a novel dialysis setting: an observational cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(4):598–607. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker R.C., Howard K., Morton R.L., Palmer S.C., Marshall M.R., Tong A. Patient and caregiver values, beliefs and experiences when considering home dialysis as a treatment option: a semi-structured interview study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;31(1):133–141. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall M.R., Supershad S. Health related quality of life (HRQoL) in community house hemodialysis (CHHD) versus home hemodialysis (Home HD) [abstract] J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:441A. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas J., Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kjellstrand C., Buoncristiani U., Ting G. Survival with short-daily hemodialysis: association of time, site, and dose of dialysis. Hemodial Int. 2010;14(4):464–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2010.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jun M., Jardine M.J., Gray N. Outcomes of extended-hours hemodialysis performed predominantly at home. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(2):247–253. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pauly R.P., Maximova K., Coppens J. Patient and technique survival among a Canadian multicenter nocturnal home hemodialysis cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(10):1815–1820. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00300110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinhandl E.D., Liu J., Gilbertson D.T., Arneson T.J., Collins A.J. Survival in daily home hemodialysis and matched thrice-weekly in-center hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(5):895–904. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011080761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Culleton B.F., Walsh M., Klarenbach S.W. Effect of frequent nocturnal hemodialysis vs conventional hemodialysis on left ventricular mass and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(11):1291–1299. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.11.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocco M.V., Lockridge R.S., Beck G.J. The effects of frequent nocturnal home hemodialysis: the Frequent Hemodialysis Network Nocturnal Trial. Kidney Int. 2011;80(10):1080–1091. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong A., Palmer S., Manns B. The beliefs and expectations of patients and caregivers about home haemodialysis: an interview study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker R.C., Howard K., Tong A., Palmer S.C., Marshall M.R., Morton R.L. The economic considerations of patients and caregivers in choice of dialysis modality. Hemodial Int. 2016;20(4):634–642. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanson C.S., Chapman J.R., Craig J.C. Patient experiences of training and transition to home haemodialysis: a mixed-methods study. Nephrology. 2016;22(8):631–641. doi: 10.1111/nep.12827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Namiki S., Rowe J., Cooke M. Living with home-based haemodialysis: insights from older people. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(3-4):547–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones D.J., Harvey K., Harris J.P., Butler L.T., Vaux E.C. Understanding the impact of haemodialysis on UK National Health Service patients’ well-being: a qualitative investigation. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(1-2):193–204. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polaschek N. Haemodialysing at home: the client experience of self-treatment. EDTNA/ERCA J. 2005;31(1):27–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2005.tb00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polaschek N. Managing home dialysis: the client perspective on independent treatment. Ren Soc Australasia J. 2006;2(3):53–63. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia-Garcia G., Jha V., Li P.K.T. Chronic kidney disease in disadvantaged populations. Transplantation. 2015;99(1):13–16. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morton R.L., Schlackow I., Mihaylova B., Staplin N.D., Gray A., Cass A. The impact of social disadvantage in moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease: an equity-focused systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;31(1):46–56. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker R.C., Walker S., Morton R.L., Tong A., Howard K., Palmer S.C. Māori patients' experiences and perspectives of chronic kidney disease: a New Zealand qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker R., Marshall M., Morton R.L., McFarlane P., Howard K. The cost effectiveness of contemporary home haemodialysis modalities compared to facility haemodialysis: a systematic review of full economic evaluations. Nephrology. 2014;19(8):459–470. doi: 10.1111/nep.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parry O., Bancroft A., Gnich W., Amos A. Nobody home? Issues of respondent recruitment in areas of deprivation. Crit Public Health. 2001;11(4):305–317. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Item S1.