Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Dialysis patients judge health-related quality of life (HRQoL) as an essential outcome. Remarkably, little is known about HRQoL differences between home dialysis and in-center hemodialysis (HD) patients worldwide.

Study Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting & Study Populations

Search strategies were performed on the Cochrane Library, Pubmed, and EMBASE databases between 2007 and 2019. Home dialysis was defined as both peritoneal dialysis and home HD.

Selection Criteria for Studies

Randomized controlled trials and observational studies that compared HRQoL in home dialysis patients versus in-center HD patients.

Data Extraction

The data extracted by 2 authors included HRQoL scores of different questionnaires, dialysis modality, and subcontinent.

Analytical Approach

Data were pooled using a random-effects model and results were expressed as standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% CIs. Heterogeneity was explored using subgroup analyses.

Results

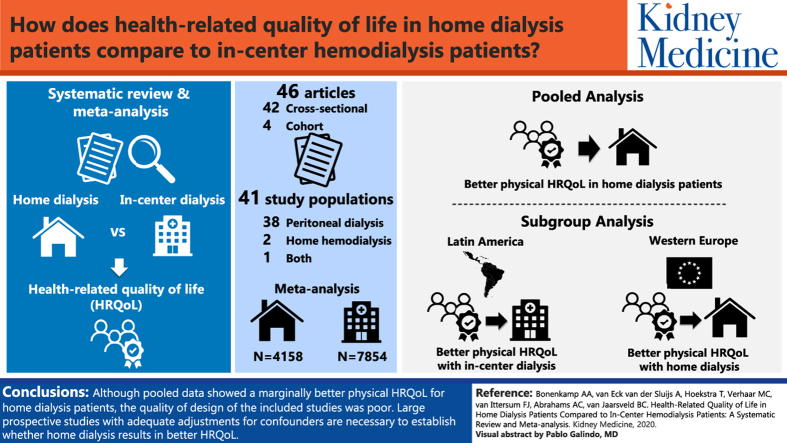

Forty-six articles reporting on 41 study populations were identified. Most studies were cross-sectional in design (90%), conducted on peritoneal dialysis patients (95%), and used the 12-item or 36-item Short-Form Health Survey questionnaires (83%). More than half the studies showed moderate or high risk of bias. Pooled analysis of 4,158 home dialysis patients and 7,854 in-center HD patients showed marginally better physical HRQoL scores in home dialysis patients compared with in-center HD patients (SMD, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.24), although heterogeneity was high (I2>80%). In a subgroup analysis, Western European home dialysis patients had higher physical HRQoL scores (SMD, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.17 to 0.61), while home dialysis patients from Latin America had lower physical scores (SMD, −0.20; 95% CI, −0.28 to −0.12). Mental HRQoL showed no difference in all analyses.

Limitations

No randomized controlled trials were found and high heterogeneity among studies existed.

Conclusions

Although pooled data showed marginally better physical HRQoL for home dialysis patients, the quality of design of the included studies was poor. Large prospective studies with adequate adjustments for confounders are necessary to establish whether home dialysis results in better HRQoL.

Trial Registration

PROSPERO 95985.

Index Words: Home dialysis, home hemodialysis, in-center hemodialysis, meta-analysis, peritoneal dialysis, quality of life, systematic review

Graphical abstract

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is associated with poor survival. Patients starting on dialysis therapy have a median 5-year survival rate of only 45%.1 Observational studies comparing patients performing home dialysis, mostly peritoneal dialysis (PD), with in-center hemodialysis (HD) show comparable survival between groups.2, 3, 4 Therefore, these survival studies will not help patients in choosing a dialysis modality.

Counterintuitive to what some clinicians assume, patients with ESRD consider quality of life (QoL) far more important than survival.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Many patients experience dialysis as a heavy burden; they even have poorer health-related QoL (HRQoL) than patients with diabetes or malignancies.11,12 Patients also indicate HRQoL aspects as important research topics.13,14 This has affected the research performed in the medical field during the last decade, with focus shifting from clinical outcomes to patient-reported outcomes.15,16 Indeed, the number of articles reporting HRQoL in dialysis patients has multiplied during the last 10 years.

Reducing the impact of ESRD and its treatment on daily life could potentially improve HRQoL. Performing dialysis at home, instead of being treated with in-center HD, has the advantage of more independence and flexibility during the day.17, 18, 19, 20 Moreover, due to the possibility of self-care and fewer hospital visits with home-based therapies, patients are able to return to work and engage in daily social activities.18,21, 22, 23 Home HD (HHD) enables an intensified dialysis regimen, allowing a reduction in medication burden.24 All these factors could contribute to an improvement in HRQoL.

Many cross-sectional and some cohort studies from different regions across the world have reported on HRQoL of home dialysis patients in comparison to in-center HD patients. Interpretation of these studies is hampered by a large variety in type of questionnaire used and applied study design.25, 26, 27 In addition, because these studies are conducted in different countries, disparity exists in study populations since the percentage of patients receiving home dialysis varies across the world. This difference in practice patterns, together with a difference in local cultures, is suggested to influence HRQoL.28 Investigators of the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study found different HRQoL scores between in-center HD patients across Japan, Europe, and the United States after adjustment for several confounders, including comorbid conditions.28 Due to inequalities among studies, it is difficult to determine whether home dialysis patients have better HRQoL. Differences in HRQoL of home dialysis patients and in-center HD patients should be interpreted in relation to the country of residence.

Hence, a systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to summarize and evaluate the available studies on HRQoL of home dialysis and in-center HD patients, with a special focus on differences across the world.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

The Cochrane Library, PubMed, and EMBASE databases were searched for relevant articles using all synonyms and abbreviations of the terms “dialysis” and “quality of life” (Table S1). The search was limited to publications during the last 10 years because the perception of QoL in patients treated with dialysis has changed over time, for example, by improved metabolic control over the years.29 After removing the duplicates, 2 authors (A.A.B. and A.v.E.v.d.S.) independently performed screening of titles and abstracts according to predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. All articles comparing the HRQoL of adult (ie, ≥18 years) home dialysis patients with the HRQoL of in-center HD patients were included. Articles other than randomized controlled trials and observational studies were excluded, such as validation and reliability studies on QoL questionnaires. In addition, articles in a language other than English were excluded.

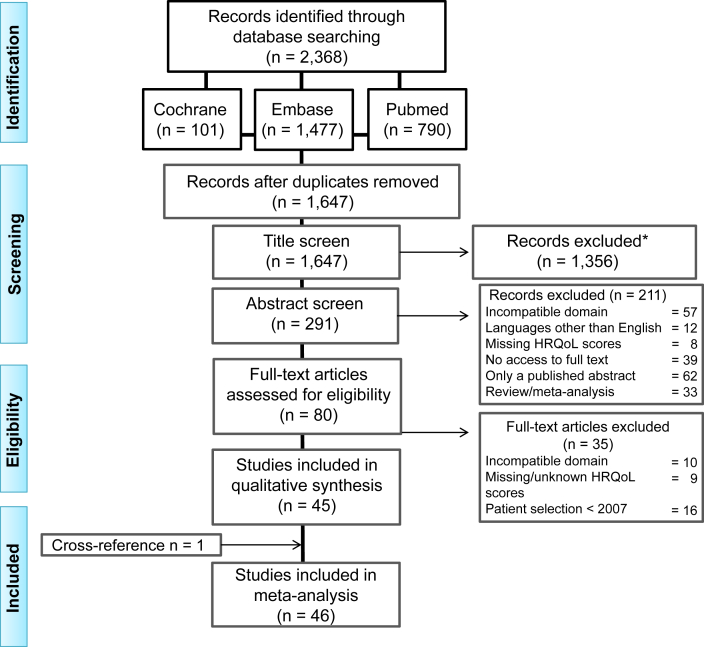

The remaining articles were read full text by 2 authors (A.A.B. and A.v.E.v.d.S.) and screened for additional references. All articles assessing HRQoL by applying worldwide most commonly used questionnaires30 were included (Table S2). The full-text articles were also checked for outdated patient data (data collected before 2007), which was reason for exclusion, and missing HRQoL scores. When no quantitative scores were reported for home dialysis and in-center HD patients, the authors were e-mailed. If they provided the quantitative data, the article was subsequently included in the critical appraisal. Final inclusion was based on consensus between the 2 authors (A.A.B. and A.v.E.v.d.S.). In case they failed to reach consensus, a third author (T.H.) was asked for an opinion that was decisive. The selection process is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Selection flow diagram. Abbreviation: HRQoL, health-related quality of life. ∗Exclusion criteria: articles describing data older than 10 years, case reports, congress abstracts, editorials, language other than English, letters, opinion papers, reviews, and validation and reliability studies on quality of life questionnaires.

Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed and checked by 2 authors (A.A.B. and A.v.E.v.d.S.). The included studies were structured according to dialysis modality, country and subcontinent of conductance, number of participants with characteristics (age, dialysis vintage, and sex), and type of HRQoL questionnaire used. From all studies, HRQoL scores were extracted and evaluated. If no standard deviation was reported, it was calculated (eg, from interquartile range [IQR], confidence interval [CI], or standard error) or substituted from another study with similar characteristics.31 Subcontinents were classified according to the regional boards of the International Society of Nephrology.32

For the meta-analysis, the Physical Component Summary (PCS) was used as score for the physical domain, and the Mental Component Summary (MCS) for the mental domain. If summary scores of the 12-item or 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF) were not available, the physical functioning or mental health score was used, respectively. If the abbreviated World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) was assessed, the physical health score was used for the physical domain, and the psychological health score for the mental domain. If the EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D) was reported, the visual analogue scale was used for the analysis.

Risk of Bias Assessment

After full-text screening, articles eligible for critical appraisal were independently appraised by 2 authors (A.A.B. and A.v.E.v.d.S.) using criteria based on the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Cohort Study checklist and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.33,34 The following criteria were assessed: study design, patient selection, comparability of patients between groups, accurate measurement of outcome, correction for confounding, duration of follow-up, selective reporting, and conflict of interest (details are provided in Table S3). They were scored as + (low risk of bias), − (high risk of bias), or ? (unclear) based on consensus between the 2 authors (A.A.B. and A.v.E.v.d.S.). In case of disagreement, a third opinion (B.C.v.J.) was decisive. After completing the critical appraisal, the corresponding authors of the articles were contacted if any uncertainty remained (ie, criteria scored as unclear). Any given comment was taken into account for the final critical appraisal.

Analytical Approach

With the extracted HRQoL scores, a meta-analysis was performed. Heterogeneity, both in clinical characteristics (eg, variability in patients) and methodological aspects (ie, design and risk of bias), was explored by visual inspection and quantified by I2 > 75%.35 Significant heterogeneity was expected due to the use of different types of HRQoL questionnaires and differences between countries regarding practice patterns and accessibility for home dialysis leading to differences between patient populations.28 Therefore, the standardized mean difference (SMD) of HRQoL scores and a random-effects model were used.

The following subgroup analyses were performed: different subcontinents and subgroups of studies according to overall risk of bias (as scored by authors: low, moderate, or high). When appropriate, type of home dialysis (PD or HHD) was compared with in-center HD. Additional analyses were conducted for the following subgroups: type of questionnaire used, different age categories (<45, 45-60, and >60 years), and dialysis vintage (<36 vs ≥36 months). Finally, a sensitivity analysis was conducted that excluded articles for which the standard deviation was calculated or substituted. All analyses were performed using Stata/SE, version 14.1, for Windows (StataCorp LP).

Protocol and Registration

This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO, the International prospective register of systematic reviews. The study protocol can be retrieved from the PROSPERO website (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/) using registration number 95985.

Results

Study Selection

The initial literature search was performed on November 21, 2017, and last updated in January 2019. The final search yielded 1,647 articles, after removal of duplicates. Subsequently, articles were excluded based on title and abstract, according to previously determined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Systematic reviews that were among these articles were checked for references before they were excluded.21,25,26,30,36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 This resulted in 1 article; however, its data collection was performed before 2007 and therefore it was excluded.47

The full texts of the remaining 80 articles were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. A total of 35 articles were excluded for the following reasons: comparison group other than in-center HD,48, 49, 50 groups were not separately presented,51, 52, 53, 54, 55 unspecified HRQoL questionnaire,56, 57, 58, 59 HRQoL data exclusively presented in graphs,60, 61, 62 unclear calculation of HRQoL scores,63,64 and outdated population data (data collected before 2007).65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80 The studies of Garg et al17 (Frequent Hemodialysis Network trials) and Jardine et al81 (ACTIVE dialysis trial) were excluded because they focused on frequent HD that was not exclusively performed at home. The remaining 45 articles were screened for additional references, resulting in 1 article that was evaluated and included (Fig 1).82

A total of 46 articles was eligible for critical appraisal.82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127 The following articles presented overlapping patient data and were appraised as one: Bujang et al91 and Liu et al,92 Chkhotua et al94 and Maglakelidze et al,95 Griva et al103 and Yang et al,104 2 articles by Kontodimopoulos111,112 and 2 articles by Theofilou,120,121 leaving 41 studies for analysis.

Study Characteristics

Characteristics of the included studies are described in Table 1. Most (32%) of the studies were conducted in Western Europe, followed by Asia (27%). From the 41 studies included, only 3 compared the HRQoL of HHD patients with in-center HD patients,82,123,124 while the rest focused on the comparison PD versus in-center HD. The predominantly used questionnaire was the SF, either as a separate questionnaire or part of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL) questionnaire (83%).

Table 1.

Study Characteristics of 41 Studies

| Study | Home Dialysis Modality | Country, Subcontinenta | No. of Patients (home/ICHD) | Age, y (SD) (home/ICHD) | Dialysis Vintage, mo (SD) (home/ICHD) | HRQoL Questionnaire | Physical Score, mean (SD) (home/ICHD) | Mental Score, mean (SD) (home/ICHD) | Study Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Wakeel83 (2012) | PD | Saudi Arabia, Middle East | 100/100 | 51.0 (13.5)/47.5 (13.8) | 34.1 (26.9)/77.2 (75.5) | KDQOL | 47.7 (23.6)/53.1 (32.0) | 61.9 (13.5)/50.5 (14.8) | Favors PD |

| Alvares84 (2012) | PD | Brazil, Latin America | 788/1,621 | 55.6 (15.3)/48.9 (14.5) | 39.7 (42.5)/53.9 (55.1) | SF | 41.0 (9.4)/43.0 (9.6) | 44.7 (8.0)/44.6 (7.6) | Favors ICHD |

| Atapour85 (2016) | PD | Iran, Middle East | 46/46 | 51.0 (12.5)/47.8 (10.6) | 18.8 (13.7)/24.4 (14.8) | SF | 60.5 (10.4)/56.2 (10.3) | 55.7 (7.1)/55.1 (6.2) | Favors PD |

| Barata86 (2015) | PD | Portugal, Western Europe | 31/94 | NA | NA | WHOQOL-BREF | 61.7 (12.7)/43.7 (13.9) | 56.1 (11.4)/46.0 (12.2) | Favors PD |

| Basok87 (2009) | PD | Turkey, Eastern Europe | 21/24 | 45.2 (8.9)/43.1 (12.4) | NA | SF | 43.2 (9.8)/47.4 (10.2) | 44.5 (10.9)/50.2 (12.6) | NA |

| Baykan88 (2012) | PD | Turkey, Eastern Europe | 41/42 | 40.6 (11.9)/49.1 (12.0) | NA | SF | 53.2 (7.6)/47.0 (9.2) | 45.2 (6.7)/42.2 (6.7) | NA |

| Borowiak89 (2009) | PD | Poland, Eastern Europe | 50/50 | 58.9 (13.2)/59.6 (13.4) | NA | EQ-5D VASb | 55.3 (21.7)/53.2 (16.2) | 55.3 (21.7)/53.2 (16.2) | Equal |

| Brown90 (2010) | PD | UK, Western Europe | 70/70 | 73.1 (5.5)/73.4 (5.1) | 30.5 (28.3)/31.4 (26.5) | SF | 36.0 (12.1)/34.3 (9.7) | 55.0 (8.4)/51.3 (12.9) | Favors PD |

| Bujang91 (2015) and Liu92 (2014) | PD | Malaysia, Asia | 539/793 | 52.8 (15.4)/55.5 (15.3) | 45.6 (37.2)/91.2 (74.4) | WHOQOL-BREF | 55.5 (15.5)/56.6 (16.1) | 60.2 (16.0)/59.6 (17.3) | Favors PD |

| Chen93 (2017) | PD | China, Asia | 103/253 | 63.1 (12.7)/56.6 (12.1) | NA | KDQOL | 40.3 (12.0)/37.4 (12.6) | 50.3 (10.0)/51.0 (10.3) | Favors PD |

| Chkhotua94 (2011) and Maglakelidze95 (2011) | PD | Georgia, Eastern Europe | 43/120 | NA | NA | SF | 55.7 (52.2)/56.9 (53.4) | 47.5 (47.9)/49.9 (51.4) | Equal |

| Czyzewski96 (2014) | PD | Poland, Eastern Europe | 30/40 | NA | 39.6/78.0 | KDQOL | 37.5 (10.6)/34.7 (7.4) | 49.9 (7.0)/43.7 (11.1) | Equal |

| Da Silva-Gane97 (2012) | PD | UK, Western Europe | 44/80 | 48.0 (15.6)/60.6 (14.9) | NA | SF | 30.1 (6.5)/25.2 (8.8) | 45.9 (10.6)/47.6 (10.7) | Favors PD |

| De Fijter98 (2018) | PD | The Netherlands, Western Europe | 33/42 | 66.0 (14.0)/66.0 (11.0) | 16/27 | KDQOL | 43.0 (20.0)/35.0 (21.0) | 56.0 (24.0)/49.0 (20.0) | Favors PD |

| Fructuoso99 (2011) | PD | Portugal, Western Europe | 14/37 | 38.9 (13.3)/67.3 (14.9) | 22.8 (15.6)/73.2 (78.0) | KDQOL | 44.9 (5.6)/35.9 (9.0) | 46.2 (10.2)/42.6 (12.6) | Favors PD |

| Garcia-Llana100 (2013) | PD | Spain, Western Europe | 31/30 | 47.9 (15.9)/60.6 (16.7) | 31.4 (28.6)/56.9 (81.7) | SF | 39.4 (8.7)/34.3 (8.7) | 49.8 (11.5)/47.1 (10.7) | Favors PD |

| Ginieri-Coccossis101 (2008) | PD | Greece, Western Europe | 48/41 | 64.1 (10.4)/65.3 (8.4) | 43.4 (24.0)/49.8 (30.8) | WHOQOL-BREF | 13.5 (2.8)/12.4 (3.8) | 13.2 (3.2)/12.9 (3.5) | Favors PD |

| Goncalves102 (2015) | PD | Brazil, Latin America | 116/222 | 58 (13.9)/54.4 (15.2) | NA | KDQOL | 45.8/52.8 | 44.3/56.6 | Favors ICHD |

| Griva103 (2014) and Yang104 (2015) | PD | Singapore, Asia | 266/236 | 59.3 (12.5)/54.4 (10.6) | 42.6 (39.4)/76.4 (66.5) | KDQOL | 37.1 (9.7)/38.9 (9.6) | 46.6 (11.2)/46.3 (10.4) | Favors ICHD |

| Günalay105 (2018) | PD | Turkey, Eastern Europe | 10/50 | 52.4 (15.1)/50.0 (18.9) | 38.5 (14.2)/53.5 (48.3) | EQ-5D VASb | 58.1 (13.1)/66.7 (22.3) | 58.1 (13.1)/66.7 (22.3) | Equal |

| Ibrahim106 (2011) | PD | Malaysia, Asia | 91/183 | NA | NA | SF | 74.6/68.4 | 77.1/70.9 | Favors PD |

| Ikonomou107 (2015) | PD | Greece, Western Europe | 39/90 | 58.0 (16.0)/57.9 (13.8) | NA | SF | 42.4 (10.0)/40.7 (11.3) | 52.3 (9.1)/49.3 (10.3) | Equal |

| Iyasere108 (2016) | PD | UK, Western Europe | 129/122 | 76.0/75.0 | 22.0/27.5 | SF | 33.0/ 31.7 | 49.3/50.8 | Equal |

| Kang109 (2017) | PD | Korea, Asia | 366/1,250 | 54.1 (11.9)/56.4 (13.2) | 63.6 (46.8)/61.2 (55.2) | KDQOL | 58.5 (23.0)/61.9 (21.2) | 55.5 (24.9)/59.8 (21.2) | Favors ICHD |

| Kim110 (2013) | PD | Korea, Asia | 65/172 | NA | NA | KDQOL | 38.7 (9.0)/39.3 (9.7) | 44.8 (6.4)/44.6 (7.0) | Favors PD |

| Kontodimopoulos111 (2008) and Kontodimopoulos112 (2009) | PD | Greece, Western Europe | 65/642 | 58.7 (12.9)/58.1 (14.9) | 63.6 (67.2)/74.4 (68.4) | SF | 49.2 (30.7)/49.2 (30.6) | 53.0 (26.1)/55.1 (22.7) | Equal |

| Nakayama113 (2015) | PD | Japan, Asia | 102/77 | 62.5 (12.0)/63.5 (12.4) | NA | SF | 25.4 (25.3)/32.1 (20.6) | 45.6 (12.1)/46.1 (10.5) | N/A |

| Neumann114 (2018) | PD | Germany, Western Europe | 153/200 | 59.0 (15.4)/59.8 (16.0) | NA | SF |

Baseline: 38.3 (9.8)/39.9 (10.8) 12 mo: 35.4 (11.6)/37.9 (11.5) |

Baseline: 52.1 (9.4)/52.1 (10.0) 12 mo: 45.8 (10.6)/46.1 (11.6) |

Equal |

| Okpechi115 (2013) | PD | South Africa, Africa | 26/56 | 36.0 (6.1)/38.6 (10.5) | 14.5 (11.6)/49.8 (71.5) | KDQOL | 67.5 (27.5)/65.4 (53.1) | 75.0 (23.5)/74.6 (21.0) | Equal |

| Ören116 (2013) | PD | Turkey, Eastern Europe | 125/175 | 46.4 (14.6)/47.6 (15.3) | 45.4 (34.8)/94.4 (60.0) | SF | 58.4 (25.9)/48.6 (26.5) | 63.3 (18.9)/57.0 (19.8) | Favors PD |

| Painter82 (2012) | HHD | USA, North America | 10/13 | 42.6 (12.4)/45.5 (10.4) | 33.8 (44.3)/28.5 (21.2) | KDQOL |

Baseline: 45.3 (11.3)/48.8 (10.0) 6 mo: 49.6 (9.1)/48.4 (7.4) |

Baseline: 48.1 (14.6)/51.1 (9.1) 6 mo: 48.9 (12.6)/51.7 (9.6) |

Favors HHD |

| Ramos117 (2015) | PD | Brazil, Latin America | 60/257 | 56.5 (15.3)/57.9 (15.9) | NA | SF | 51.3 (27.8)/53.5 (29.7) | 71.7 (20.4)/68.7 (22.6) | Equal |

| Ruiz de Alegría - Fernández de Retana118 (2013) | PD | Spain, Western Europe | 45/53 | 50.8 (13.3)/52.3 (13.1) | NA | SF |

3 mo: 42.6 (8.9)/40.8 (8.9) 6 mo: 40.6 (9.8)/42.2 (9.7) 12 mo: 43.9 (9.8)/39.9 (9.7) |

3 mo: 50.5 (13.0)/46.3 (13.4) 6 mo: 50.3 (11.6)/49.3 (11.6) 12 mo: 50.5 (11.6)/49.6 (11.6) |

NA |

| Tannor119 (2017) | PD | South Africa, Africa | 48/58 | 36.1 (10.7)/42.8 (9.8) | 26.4/72.0 | KDQOL | 55.5 (21.7)/54.7 (19.4) | 62.7 (19.7)/68.6 (17.9) | Equal |

| Theofilou120 (2011) and Theofilou121 (2013) | PD | Greece, Western Europe | 60/84 | 64.3 (12.5)/58.1 (16.1) | 38.4 (24.0)/87.6 (85.2) | WHOQOL-BREF | 13.7 (3.0)/12.7 (3.7) | 13.4 (3.1)/13.3 (3.7) | Favors PD |

| Turkmen122 (2012) | PD | Turkey, Eastern Europe | 64/90 | 52.4 (15.3)/55.0 (15.7) | 19.8 (14.3)/22.7 (13.1) | SF | 47.6 (18.5)/59.4 (20.7) | 41.7 (17.2)/63.9 (20.6) | Favors ICHD |

| Watanabe123 (2014) | HHD | Japan, Asia | 46/34 | 54.0 (8.3)/57.1 (7.6) | 76.8 (68.4)/88.8 (99.6) | KDQOL | 48.7 (9.2)/37.1 (12.9) | 51.2 (8.9)/49.6 (6.2) | Favors HHD |

| Wright124 (2015)c | HHD | USA, North America | 22/29 | NA | NA | KDQOL | 40.4 (12.7)/42.8 (9.8) | 50.6 (9.4)/50.4 (10.0) | Equal |

| Wright124 (2015)c | PD | USA, North America | 26/29 | NA | NA | KDQOL | 43.2 (8.8)/42.8 (9.8) | 51.1 (8.2)/50.4 (10.0) | Equal |

| Wu125 (2013) | PD | China, Asia | 93/97 | 54.5 (15.5)/58.3 (17.5) | 25.5/31.0 | SF | 34.0 (11.9)/30.5 (14.5) | 41.3 (10.0)/38.5 (12.0) | Equal |

| Ying126 (2014) | PD | Malaysia, Asia | 73/147 | NA | NA | SF | 60.2 (21.9)/49.6 (20.2) | 67.1 (19.4)/58.0 (20.3) | Favors PD |

| Yongsiri127 (2014) | PD | Thailand, Asia | 26/34 | 53.0 (14.4)/61.1 (15.5) | NA | WHOQOL-BREF | 3.0 (0.9)/2.9 (0.8) | 3.7 (0.7)/3.7 (0.6) | Equal |

| Total | 4,158/7,854 | 55.9 (13.8)/54.8 (14.1) | 34.1d (22.8-43.4)/56.9d (31.0-77.2) |

Abbreviations: EQ-5D VAS, EuroQol-5D visual analogue scale; HHD, home hemodialysis; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; ICHD, in-center hemodialysis; KDQOL, Kidney Disease Quality of Life instrument; NA, not available; PD, peritoneal dialysis; SD, standard deviation; SF, Short Form Health Survey (12-item or 36-item); UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America; WHOQOL-BREF, abbreviated World Health Organization Quality of Life questionnaire.

The regional boards of the International Society of Nephrology were used for the classification of countries into subcontinents.

EQ-5D VAS score was used as a surrogate for both physical score and mental score.

Wright et al included 3 patient populations: HHD, PD, and ICHD.

Median with interquartile range.

Mean age of the home dialysis population was 55.9 ± 13.8 years, while in-center HD patients were slightly younger (mean age, 54.8 ± 14.1 years). There was a difference in dialysis vintage between both groups, with a median of 34.1 months for home dialysis patients (IQR, 22.8-43.4 months) and 56.9 months for in-center HD patients (IQR, 31.0-77.2 months). Most (55%) of the total dialysis population was male. One study was conducted in females only.87 Half the home dialysis population was male (range, 27%-90%) compared with 57% of the in-center HD population (range, 44%-85%). In the included studies, there were no randomized controlled trials of in-center HD versus home dialysis. Furthermore, most studies had a cross-sectional design, comparing prevalent patients receiving in-center HD with prevalent home dialysis patients.

It should be noted that 4 studies were observational cohort studies with a longitudinal follow-up. Da Silva-Gane et al97 assessed HRQoL of dialysis patients every 3 months until 12 months after dialysis initiation. Baseline PCS scores were lower in in-center HD patients. However, after a median follow-up period of 14.7 months, HRQoL between dialysis modalities was equal. Because follow-up results of PD and in-center HD patients were not shown in the article, in the following meta-analysis, only baseline data of this study could be used. The study by Neumann et al114 investigated the change in social networks and social support, and their association with HRQoL, of dialysis patients over a 12-month period. The PCS and MCS scores of PD and in-center HD patients decreased equally during follow-up. The follow-up HRQoL scores at 12 months were used in this meta-analysis. The study by Painter et al82 examined exercise capacity after modality switch from in-center HD to HHD, yet also assessed HRQoL. Modality switch was associated with a significant improvement in physical HRQoL scores after 6 months. The follow-up HRQoL scores at 6 months were used in this meta-analysis. The study by Ruiz de Alegría-Fernández de Retana et al118 related coping mechanisms to HRQoL. SF-36 questionnaires were collected at 3, 6, and 12 months after dialysis initiation. Separate HRQoL scores for PD and in-center HD were obtained from the author. These unpublished data showed improvement in MCS scores for in-center HD patients, but PCS scores remained the same in both groups. HRQoL scores 12 months after initiation of dialysis treatment were used in this meta-analysis.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Results of the critical appraisal are presented in Table S4. Seventeen of the 41 studies were assessed as having an overall low risk of bias. There was a general lack of adequate presentation of patient characteristics, with 6 studies presenting baseline data without separation by dialysis modality86,106,110,126 or no baseline data at all.95,96 Few studies adequately adjusted HRQoL scores for confounding between groups.84,97,98,108,109,114 Apart from adjustment for confounders, also a stratified analysis was considered as a low risk of bias. HRQoL, as a patient-reported outcome measure, should be self-reported or assessed by a trained research assistant.128 For 8 studies, it was unknown whether the professional performing the interview was trained to assess HRQoL, leading to potential bias in outcome assessment.89,99,102,106,115,116,120,126

Meta-analysis

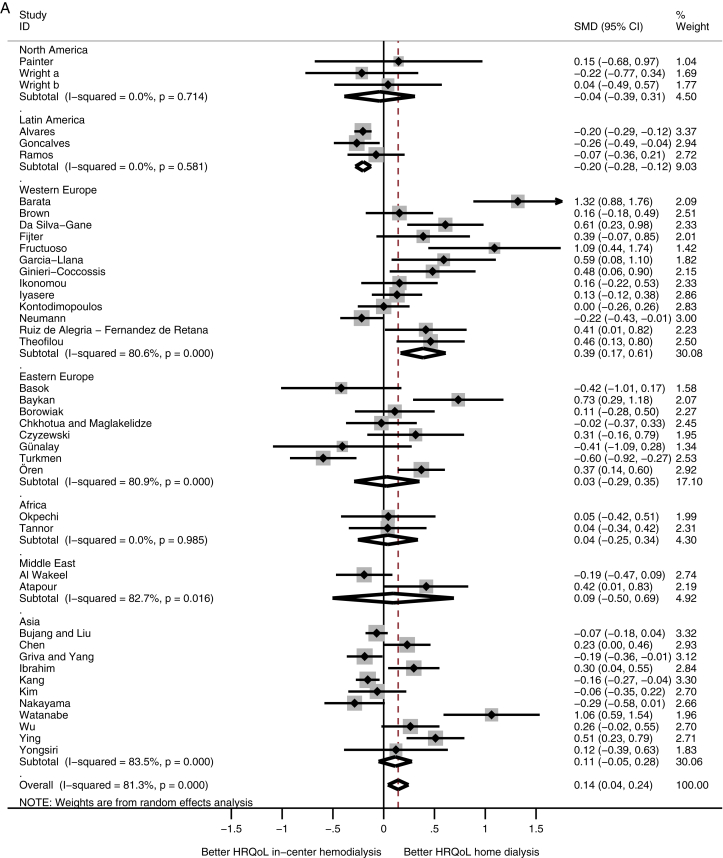

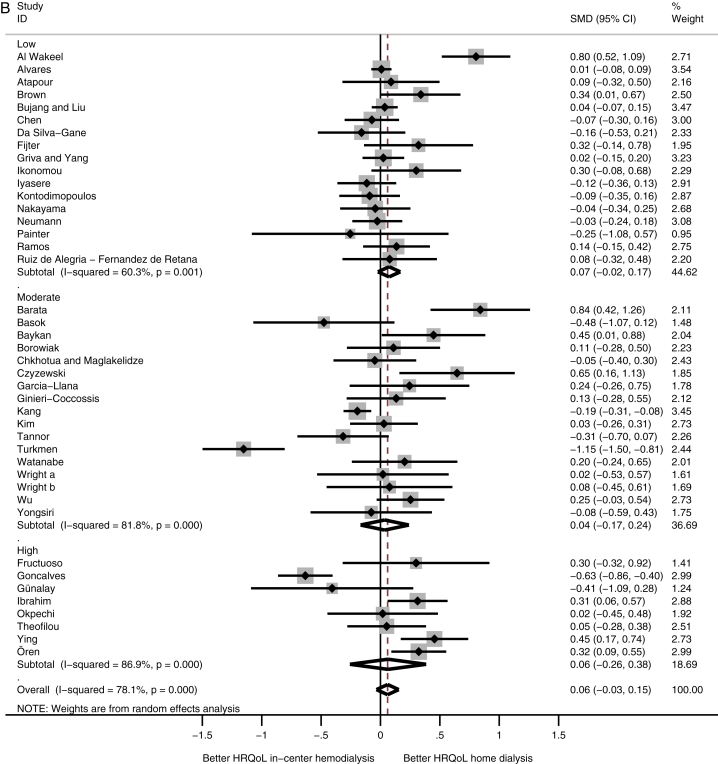

The included studies for the meta-analysis compared HRQoL for a total of 4,158 home dialysis patients with 7,854 in-center HD patients. The study by Wright et al compared 2 home dialysis populations (HHD and PD) with in-center HD patients and is presented twice in the meta-analysis.124 Although heterogeneity was high, HRQoL on the physical domain was marginally better in home dialysis patients compared with in-center HD patients, with an SMD of 0.14 (95% CI, 0.04 to 0.24). HRQoL on the mental domain was equal between the 2 groups (SMD, 0.06; 95% CI, −0.03 to 0.15).

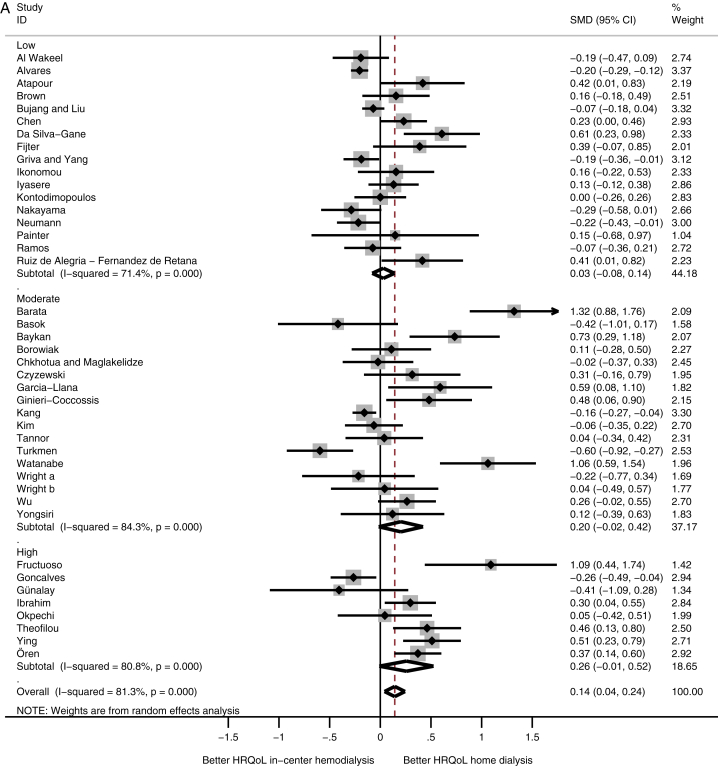

A comparison among subcontinents showed that patients receiving home dialysis in Western Europe had higher physical HRQoL scores compared with in-center HD patients (SMD, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.17 to 0.61), whereas patients receiving home dialysis from Latin America had lower physical HRQoL scores (SMD, −0.20; 95% CI, −0.28 to −0.12; Fig 2A). HRQoL on the mental domain showed no difference among the subcontinents (Fig 2B).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among subcontinents. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SMD, standardized mean difference. (A) Physical and (B) mental HRQoL among subcontinents.

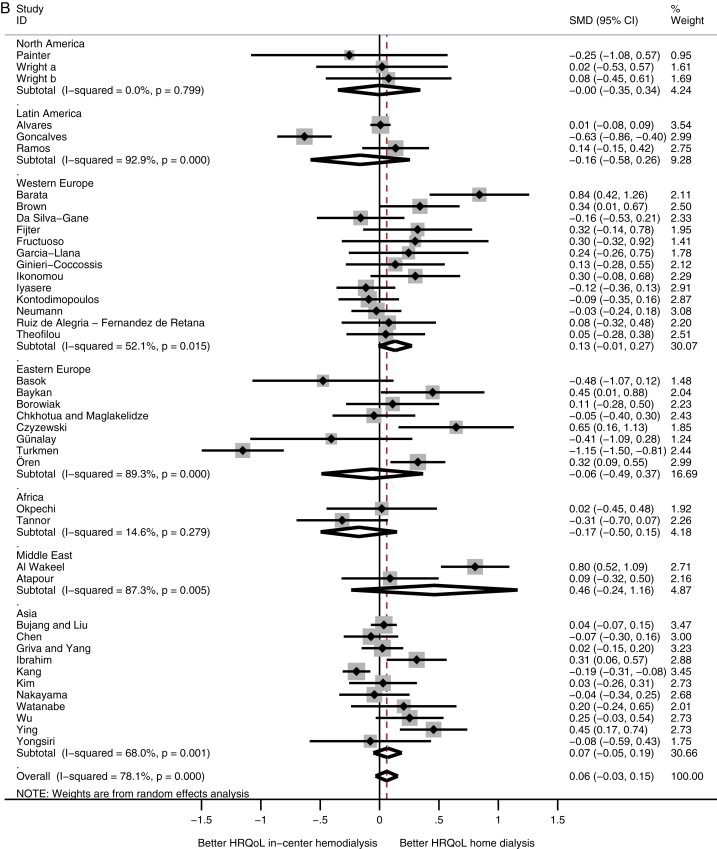

If studies were divided according to overall level of bias, increased risk of bias was associated with an increase in SMD in physical HRQoL (high risk of bias: SMD, 0.26; 95% CI, −0.01 to 0.52; Fig 3A). For the mental domain, there was no difference among the different levels of bias (Fig 3B). The subgroup analysis regarding type of home dialysis (PD or HHD) provided no additional insights, recognizing that only 3 studies focused on HHD (data not shown). Heterogeneity remained after all subgroup analyses. Additional analyses regarding type of questionnaire used, different age categories, and dialysis vintage did not alter results or influence heterogeneity (Figs S1A and B and S2A and B).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among level of bias. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SMD, standardized mean difference. (A) Physical and (B) mental HRQoL among level of bias.

The standard deviation for the HRQoL scores in 5 studies had to be calculated, if sufficient data were available,95,98,108 or substituted.102,106 Also, WHOQOL-BREF scores in 2 studies were transformed into a 100-scale.101,121 To further explore the robustness of data, sensitivity analysis was performed that did not change the mentioned results.

Discussion

This meta-analysis shows better physical HRQoL for patients treated with home dialysis compared with patients treated with in-center HD, while mental HRQoL is comparable between these 2 patient groups. However, higher physical HRQoL scores in home dialysis patients were found only in Western Europe. Home dialysis patients from Latin America were found to have poorer physical HRQoL compared with in-center HD patients. No studies were conducted in Oceania or Russia and only a few in Africa and the Middle East, hampering the comparison regarding HRQoL in the dialysis population worldwide. Furthermore, it should be noted that included studies were generally low in quality and showed high heterogeneity. Therefore, the conclusion regarding better HRQoL of home dialysis patients compared with in-center HD patients lacks the necessary robustness.

The finding that home dialysis patients from Western Europe had better physical HRQoL compared with in-center HD patients could be explained because PD patients from some of the Western European studies were younger due to practice patterns, suggestive for confounding by indication.97,99,100 Although most studies performed statistical adjustments of their analyses, important residual confounding between these patient groups might still be present. In contrast to West European home dialysis patients, those from Latin America were found to have poorer physical HRQoL. However, these results could also be subject to confounding by indication because in Brazil, the country in which these studies were conducted, it is common practice to perform PD only if patients are not eligible for in-center HD.84 Brazilian in-center HD patients may be healthier and therefore physically in better condition than PD patients in general.84,102 This was emphasized by Ramos et al117 because in this study, PD and in-center HD patients were more comparable and physical HRQoL scores were found to be equal.

The differences in HRQoL of dialysis patients across the world could also be explained by differences in access to dialysis. Liyanage et al129 modeled inaccessibility among countries and estimated that at least 47% and at most 73% of the world population has no access to renal replacement therapy (RRT). In Latin America, up to 52% of patients with ESRD have no access to dialysis, while Africa and Asia have the highest inaccessibility rates, 83% and 91%, respectively.129 In South Africa, more than half the patients in need of RRT cannot be treated.130,131 Due to limited resources, prolonged maintenance dialysis is not applied and only patients suitable for transplantation are eligible for RRT. As a result, the elderly or unemployed and patients with diabetes or drug abuse are rarely accepted for dialysis treatment.130,131 In India, less than 10% of patients start RRT and yet more than two-thirds cease dialysis treatment due to financial problems, often within 3 months. Most dialysis facilities belong to private hospitals and although PD has gained popularity, due to financial restrictions both home dialysis and in-center HD are reserved for the rich minority.132 In most countries of North and South Asia, dialysis care is publicly funded, as is most common in the rest of the world,whereas only 31% of countries in Southeast Asia provide free publicly funded dialysis care.133 Particularly patients from low-income countries worldwide depend on private funding.133,134 In high-income countries, inaccessibility is very low, with a maximum of 30%, in comparison to 98% in low-income countries.129,135 Due to these accessibility issues, dialysis patients from high-income countries (eg, Western Europe) substantially differ from patients worldwide, which could influence HRQoL scores importantly.

This meta-analysis also underscores the effect of bias in HRQoL. A high risk of bias was associated with better HRQoL in favor of home dialysis if compared with studies with low risk of bias. Remarkably, in all studies with a high risk of bias, HRQoL questionnaires were not completed by patients themselves, yet were administered by researchers for whom it was unclear whether they had been trained. In the manual of the Short Form Health Survey, it is stated that the questionnaire should be completed by the patient alone before any contact with the clinician to avoid influencing the patient and reduce the risk of socially desirable answers.128 Hood et al136 has found that assessment by an interviewer is a potential risk of significant bias. The aforementioned conclusion is confirmed by results of this meta-analysis.

No randomized controlled trials with randomization between home and in-center dialysis were found in the literature search, presumably because previous experiences have shown that a patient’s choice between home dialysis and in-center HD is too fundamental to let it be determined by fate.20,137 In this meta-analysis, most studies had a cross-sectional design and did not adjust for confounding, even though populations were not comparable at baseline. However, patients performing home dialysis are principally different from in-center HD patients. Therefore, in cross-sectional studies, the observed associations are less likely to be causative. Korevaar et al138 showed that patients starting home dialysis had higher HRQoL scores than in-center HD patients even in adjusted analysis, while Manns et al139 reported that choosing home dialysis improved HRQoL even before initiation of home dialysis. The prospective studies in this meta-analysis had a follow-up period of 6 to 12 months. However, it might take longer for patients to return to social activities and work, 2 factors suggested to be of major influence on HRQoL.18,21, 22, 23 Therefore, prospective studies with at least 1 year of follow-up will be necessary to provide a valid assessment of HRQoL of home dialysis patients.

Unfortunately, few studies reported on disease-specific domains, whereas dialysis modality possibly has a greater impact on specific symptoms or domains than on generic physical and mental HRQoL scores.140,141 Future studies should also incorporate disease-specific domains as an outcome measure.

The most important limitation of this meta-analysis is the high heterogeneity among studies. High heterogeneity remained despite several subgroup analyses, emphasizing the clinical and methodological diversity among studies. However, this systematic review and meta-analysis provides a detailed overview of current literature on HRQoL of home dialysis patients across the world, while previous reviews were unable to provide such a detailed insight.25, 26, 27 Another limitation was that only 3 studies focused on HHD, illustrating the knowledge gap regarding this modality.

In conclusion, although pooled data in this meta-analysis show marginally better physical HRQoL for home dialysis patients; the quality of design of the included studies is poor and large heterogeneity among studies exist. Therefore, no definitive conclusions on HRQoL of patients treated with home dialysis can be drawn. Large prospective studies with adequate follow-up and adjustments for confounders are necessary to evaluate HRQoL of home dialysis patients.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Anna A. Bonenkamp, MD, Anita van Eck van der Sluijs, MD, Tiny Hoekstra, PhD, Marianne C. Verhaar, MD, PhD, Frans J. van Ittersum, MD, PhD, Alferso C. Abrahams, MD, PhD, and Brigit C. van Jaarsveld, MD, PhD.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea: AAB, ACA, BCvJ; literature search: AAB, AvEvdS; appraised risk of bias: AAB, AvEvdS; data extraction: AAB, AvEvdS; third opinion search regarding the literature search and appraisal for risk of bias: TH, BCvJ; statistical analysis: AAB, AvEvdS, TH; data interpretation: AAB, AvEvdS, FJvI, ACA, BCvJ; supervision/mentorship: MCV, FJvI, ACA, BCvJ. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

None.

Financial Disclosure

Prof van Ittersum was a nonexecutive director of Nefrovisie, the national quality agency for the treatment of kidney diseases. The remaining authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgements

This work is part of the research programme DOMESTICO, which is financed by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw, project number 843004116). We thank the personnel of VU Medical Library for assistance in performing the search in the databases used.

Prior Presentation

The results presented in this article have not been published previously, except in abstract form at the 56th ERA-EDTA Congress 2019, Budapest, Hungary, June 13 to 16, 2019.

Peer Review

Received July 26, 2019. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from an Associate Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form November 14, 2019.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Figure S1: Meta-analysis of health-related quality of life in different questionnaires.

Figure S2: Meta-analysis of health-related quality of life in different age categories.

Table S1: Search strings for Cochrane, EMBASE, and PubMed databases

Table S2: HRQoL questionnaires

Table S3: Criteria used in risk of bias assessment

Table S4: Critical appraisal of 41 studies

Supplementary Material

Figures S1-S2; Table S1-S4.

References

- 1.Kramer A., Pippias M., Noordzij M. The European Renal Association - European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA) Registry Annual Report 2015: a summary. Clin Kidney J. 2018;11(1):108–122. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfx149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van de Luijtgaarden M.W.M., Jager K.J., Segelmark M. Trends in dialysis modality choice and related patient survival in the ERA-EDTA Registry over a 20-year period. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:120–128. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merchant A.A., Quinn R.R., Perl J. Dialysis modality and survival: does the controversy live on? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24(3):276–283. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall M.R., Walker R.C., Polkinghorne K.R. Survival on home dialysis in New Zealand. PloS One. 2014;9(5):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verberne W.R., Das-Gupta Z., Allegretti A.S. Development of an international standard set of value-based outcome measures for patients with chronic kidney disease: a report of the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) CKD Working Group. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73(3):372–384. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee M.B., Bargman J.M. Survival by dialysis modality - who cares? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(6):1083–1087. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13261215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkelstein F.O. Performance measures in dialysis facilities: what is the goal? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(1):156–158. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04780514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nissenson A.R. Improving outcomes for ESRD patients: shifting the quality paradigm. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(2):430–434. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05980613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morton R.L., Snelling P., Webster A.C. Factors influencing patient choice of dialysis versus conservative care to treat end-stage kidney disease. CMAJ. 2012;184(5):E277–E283. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manera K.E., Tong A., Craig J.C. An international Delphi survey helped develop consensus-based core outcome domains for trials in peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int. 2019;96(3):699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mittal S.K., Ahern L., Flaster E. Self-assessed physical and mental function of haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(7):1387–1394. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.7.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Sandwijk M.S., Al Arashi D., van de Hare F.M. Fatigue, anxiety, depression and quality of life in kidney transplant recipients, haemodialysis patients, patients with a haematological malignancy and healthy controls. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34(5):833–838. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Carter S.M. Patients' priorities for health research: focus group study of patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(10):3206–3214. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manns B., Hemmelgarn B., Lillie E. Setting research priorities for patients on or nearing dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(10):1813–1821. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01610214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perl J., Dember L.M., Bargman J.M. The use of a multidimensional measure of dialysis adequacy-moving beyond small solute kinetics. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(5):839–847. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08460816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black N., Burke L., Forrest C.B. Patient-reported outcomes: pathways to better health, better services, and better societies. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(5):1103–1112. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garg A.X., Suri R.S., Eggers P. Patients receiving frequent hemodialysis have better health-related quality of life compared to patients receiving conventional hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2017;91(3):746–754. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xi W., Singh P.M., Harwood L. Patient experiences and preferences on short daily and nocturnal home hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2013;17(2):201–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2012.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cases A., Dempster M., Davies M. The experience of individuals with renal failure participating in home haemodialysis: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. J Health Psychol. 2011;16(6):884–894. doi: 10.1177/1359105310393541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suri R.S., Garg A.X., Chertow G.M. Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) randomized trials: study design. Kidney Int. 2007;71(4):349–359. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller B.W., Himmele R., Sawin D.A. Choosing home hemodialysis: a critical review of patient outcomes. Blood Purif. 2018;45(1-3):224–229. doi: 10.1159/000485159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ageborg M., Allenius B.L., Cederfjall C. Quality of life, self-care ability, and sense of coherence in hemodialysis patients: a comparative study. Hemodial Int. 2005;9(suppl 1):S8–S14. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2005.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piccoli G.B., Bechis F., Iacuzzo C. Why our patients like daily hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2000;4:47–50. doi: 10.1111/hdi.2000.4.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdel-Kader K., Unruh M.L. Benefits of short daily home hemodialysis in the FREEDOM Study: is it about person, place, time, or treatment? Kidney Int. 2012;82(5):511–513. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zazzeroni L., Pasquinelli G., Nanni E. Comparison of quality of life in patients undergoing hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2017;42(4):717–727. doi: 10.1159/000484115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho Y.F., Li I.C. The influence of different dialysis modalities on the quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease: a systematic literature review. Psychol Health. 2016;31(12):1435–1465. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2016.1226307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liem Y.S., Bosch J.L., Arends L.R. Quality of life assessed with the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36-Item Health Survey of patients on renal replacement therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Value Health. 2007;10(5):390–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukuhara S., Lopes A.A., Bragg-Gresham J.L. Health-related quality of life among dialysis patients on three continents: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Kidney Int. 2003;64(5):1903–1910. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazairac A.H., De Wit G.A., Penne E.L. Changes in quality of life over time—Dutch haemodialysis patients and general population compared. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1984–1989. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyld M., Morton R.L., Hayen A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of utility-based quality of life in chronic kidney disease treatments. PLoS Med. 2012;9(9):1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Furukawa T.A., Barbui C., Cipriani A. Imputing missing standard deviations in meta-analyses can provide accurate results. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(1):7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.International Society of Nephrology, Regions. https://www.theisn.org/about-isn/regions

- 33.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme 2017. CASP (cohort study) checklist. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Cohort-Study-Checklist_2018.pdf

- 34.Wells G.A., Shea B., O'Connell D. The Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale (cohort studies) http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/nosgen.pdf

- 35.Higgins J.P.T., Green S. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]https://training.cochrane.org/handbook [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker R.C., Howard K., Morton R.L. Home hemodialysis: a comprehensive review of patient-centered and economic considerations. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;9:149–161. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S69340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Homaie R.E., Mostafavi H., Delavari S. Health-related quality of life in patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: a meta-analysis of Iranian studies. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2015;9(5):386–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishani A., Slinin Y., Greer N. Department of Veterans Affairs (US); Washington, DC: 2015. Comparative Effectiveness of Home-Based Kidney Dialysis Versus In-Center or Other Outpatient Kidney Dialysis Locations – A Systematic Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palmer S.C., Palmer A.R., Craig J.C. Home versus in-centre haemodialysis for end-stage kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:CD009535. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009535.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Avramovic M., Stefanovic V. Health-related quality of life in different stages of renal failure. Artif Organs. 2012;36(7):581–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2011.01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boateng E.A., East L. The impact of dialysis modality on quality of life: a systematic review. J Ren Care. 2011;37(4):190–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2011.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liem Y.S., Bosch J.L., Hunink M.G. Preference-based quality of life of patients on renal replacement therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Value Health. 2008;11(4):733–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aguiar R., Pei M., Qureshi A.R. Health-related quality of life in peritoneal dialysis patients: a narrative review. Semin Dial. 2019;32(5):452–462. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H., Xie L., Yang J. Symptom burden amongst patients suffering from end-stage renal disease and receiving dialysis: a literature review. Int J Nurs Sci. 2018;5(4):427–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2018.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Queeley G.L., Campbell E.S. Comparing treatment modalities for end-stage renal disease: a meta-analysis [abstract] Value Health. 2014;17(3):A290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valentijn P.P., Pereira F.A., Ruospo M. Person-centered integrated care for chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(3):375–386. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09960917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arenas V.G., Barros L.F.N.M., Lemos F.B. Quality of life: comparison between patients on automated peritoneal dialysis and patients on hemodialysis. Acta Paul Enferm. 2009;22:535–539. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang J., Huang C., Li Y. Health-related quality of life in dialysis patients with constipation: a cross-sectional study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:589–594. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S45471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osthus T.B., Preljevic V., Sandvik L. Renal transplant acceptance status, health-related quality of life and depression in dialysis patients. J Ren Care. 2012;38(2):98–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2011.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fong E., Bargman J.M., Chan C.T. Cross-sectional comparison of quality of life and illness intrusiveness in patients who are treated with nocturnal home hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(6):1195–1200. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02260507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dodson S., Osicka T., Huang L. Multifaceted assessment of health literacy in people receiving dialysis: associations with psychological stress and quality of life. J Health Commun. 2016;21(suppl 2):91–98. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2016.1179370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murali R., Sathyanarayana D., Muthusethupathy M. Assessment of quality of life in chronic kidney disease patients using the Kidney Disease Quality Of Life-Short FormTM questionnaire in indian population: a community based study. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2015;8(1):271–274. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davison S.N., Jhangri G.S. Existential and religious dimensions of spirituality and their relationship with health-related quality of life in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(11):1969–1976. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01890310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chiu Y.-W., Teitelbaum I., Misra M. Pill burden, adherence, hyperphosphatemia, and quality of life in maintenance dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(6):1089–1096. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00290109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bohlke M., Nunes D.L., Marini S.S. Predictors of quality of life among patients on dialysis in southern Brazil. Sao Paulo Med J. 2008;126(5):252–256. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802008000500002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laudanski K., Nowak Z., Niemczyk S. Age-related differences in the quality of life in end-stage renal disease in patients enrolled in hemodialysis or continuous peritoneal dialysis. Med Sci Monit. 2013;19:378–385. doi: 10.12659/MSM.883916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Theofilou P. Quality of life and mental health in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients: the role of health beliefs. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44(1):245–253. doi: 10.1007/s11255-011-9975-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Panagopoulou A., Hardalias A., Berati S. Psychosocial issues and quality of life in patients on renal replacement therapy. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2009;20(2):212–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dąbrowska-Bender M., Dykowska G., Żuk W. The impact on quality of life of dialysis patients with renal insufficiency. Patient Pref Adherence. 2018;12:577–583. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S156356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martinez-Sanchis S., Bernal M.C., Montagud J.V. Quality of life and stressors in patients with chronic kidney disease depending on treatment. Span J Psychol. 2015;18:E25. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2015.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peng Y.S., Chiang C.K., Hung K.Y. Comparison of self-reported health-related quality of life between Taiwan hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients: a multi-center collaborative study. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(3):399–405. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9755-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Conde S.A., Fernandes N., Santos F.R. Cognitive decline, depression and quality of life in patients at different stages of chronic kidney disease. J Bras Nefrol. 2010;32(3):242–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aghakhani N., Nia H.S., Zadeh S.S. Quality of life during hemodialysis and study dialysis treatment in patients referred to teaching hospitals in Urmia-Iran in 2007. Caspian J Intern Med. 2011;2(1):183–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Abreu M.M., Walker D.R., Sesso R.C. Health-related quality of life of patients recieving hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis in Sao Paulo, Brazil: a longitudinal study. Value Health. 2011;14(5 suppl 1):S119–S121. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Makkar V., Kumar M., Mahajan R. Comparison of outcomes and quality of life between hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients in Indian ESRD population. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(3):OC28–OC31. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/11472.5709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Osthus T.B., Preljevic V.T., Sandvik L. Mortality and health-related quality of life in prevalent dialysis patients: comparison between 12-items and 36-items Short-Form Health Survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Izbirak G., Akan H., Mistik S. Comparison of health-related quality of life of patients on hemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci. 2010;30(5):1595–1602. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thong M.S., van D.S., Noordzij M. Symptom clusters in incident dialysis patients: associations with clinical variables and quality of life. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(1):225–230. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Noshad H., Sadreddini S., Nezami N. Comparison of outcome and quality of life: haemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis patients. Singapore Med J. 2009;50(2):185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hallinen T., Soini E.J., Martikainen J.A. Costs and quality of life effects of the first year of renal replacement therapy in one Finnish treatment centre. J Med Econ. 2009;12(2):136–140. doi: 10.3111/13696990903119530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abdel-Kader K., Myaskovsky L., Karpov I. Individual quality of life in chronic kidney disease: influence of age and dialysis modality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(4):711–718. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05191008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Timmers L., Thong M., Dekker F.W. Illness perceptions in dialysis patients and their association with quality of life. Psychol Health. 2008;23(6):679–690. doi: 10.1080/14768320701246535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shrestha S., Ghotekar L.R., Sharma S.K. Assessment of quality of life in patients of end stage renal disease on different modalities of treatment. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2008;47(169):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mau L.W., Chiu H.C., Chang P.Y. Health-related quality of life in Taiwanese dialysis patients: effects of dialysis modality. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2008;24(9):453–460. doi: 10.1016/s1607-551x(09)70002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Malmstrom R.K., Roine R.P., Heikkila A. Cost analysis and health-related quality of life of home and self-care satellite haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(6):1990–1996. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sayin A., Mutluay R., Sindel S. Quality of life in hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and transplantation patients. Transplant Proc. 2007;39(10):3047–3053. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Molsted S., Prescott L., Heaf J. Assessment and clinical aspects of health-related quality of life in dialysis patients and patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2007;106(1):c24–c33. doi: 10.1159/000101481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lausevic M., Nesic V., Stojanovic M. Health-related quality of life in patients on peritoneal dialysis in Serbia: comparison with hemodialysis. Artif Organs. 2007;31(12):901–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2007.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kutner N.G., Zhang R., Huang Y. Association of sleep difficulty with Kidney Disease Quality of Life cognitive function score reported by patients who recently started dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(2):284–289. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03000906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kalender B., Ozdemir A.C., Dervisoglu E. Quality of life in chronic kidney disease: effects of treatment modality, depression, malnutrition and inflammation. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(4):569–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jardine M.J., Gray N.A., De Zoysa J. Design and participant baseline characteristics of ‘A Clinical Trial of IntensiVE Dialysis': the ACTIVE Dialysis Study. Nephrology. 2015;20:257–265. doi: 10.1111/nep.12385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Painter P., Krasnoff J.B., Kuskowski M. Effects of modality change on health-related quality of life. Hemodial Int. 2012;16(3):377–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2012.00676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Al Wakeel J., Al Harbi A., Bayoumi M. Quality of life in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32(6):570–574. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2012.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Alvares J., Cesar C.C., Acurcio F.A. Quality of life of patients in renal replacement therapy in Brazil: comparison of treatment modalities. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(6):983–991. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Atapour A., Nasr S., Boroujeni A.M. A comparison of the quality of life of the patients undergoing hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis and its correlation to the quality of dialysis. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2016;27(2):270–280. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.178259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barata N.E. Dyadic relationship and quality of life patients with chronic kidney disease. J Bras Nefrol. 2015;37(3):315–322. doi: 10.5935/0101-2800.20150051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Basok E.K., Atsu N., Rifaioglu M.M. Assessment of female sexual function and quality of life in predialysis, peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis, and renal transplant patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2009;41(3):473–481. doi: 10.1007/s11255-008-9475-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Baykan H., Yargic I. Depression, anxiety disorders, quality of life and stress coping strategies in hemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bulteni. 2012;22(2):167–176. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Borowiak E., Braksator E., Nowicki M. Quality of life of chronic hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin Exp Med Lett. 2009;50(1):37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brown E.A., Johansson L., Farrington K. Broadening Options for Long-term Dialysis in the Elderly (BOLDE): differences in quality of life on peritoneal dialysis compared to haemodialysis for older patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(11):3755–3763. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bujang M.A., Musa R., Liu W.J. Depression, anxiety and stress among patients with dialysis and the association with quality of life. Asian J Psychiatr. 2015;18:49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu W.J., Musa R., Chew T.F. Quality of life in dialysis: a Malaysian perspective. Hemodial Int. 2014;18(2):495–506. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen J.Y., Wan E.Y.F., Choi E.P.H. The health-related quality of life of Chinese patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Patient. 2017;10(6):799–808. doi: 10.1007/s40271-017-0256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chkhotua A., Pantsulaia T., Managadze L. The quality of life analysis in renal transplant recipients and dialysis patients. Georgian Med News. 2011;11(200):10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Maglakelidze N., Pantsulaia T., Tchokhonelidze I. Assessment of health-related quality of life in renal transplant recipients and dialysis patients. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(1):376–379. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Czyzewski L., Sanko-Resmer J., Wyzgal J. Assessment of health-related quality of life of patients after kidney transplantation in comparison with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Ann Transplant. 2014;19:576–585. doi: 10.12659/AOT.891265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Da Silva-Gane M., Wellsted D., Greenshields H. Quality of life and survival in patients with advanced kidney failure managed conservatively or by dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(12):2002–2009. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01130112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.de Fijter C.W.H., Diepen A.T., Amiri F. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) argue against the limited use of peritoneal dialysis in end-stage renal disease. Clin Nephrol. 2018;90(2):94–101. doi: 10.5414/CN109369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fructuoso M., Castro R., Oliveira L. Quality of life in chronic kidney disease. Nefrologia. 2011;31(1):91–96. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2010.Jul.10483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Garcia-Llana H., Remor E., Selgas R. Adherence to treatment, emotional state and quality of life in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing dialysis. Psicothema. 2013;25(1):79–86. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2012.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ginieri-Coccossis M., Theofilou P., Synodinou C. Quality of life, mental health and health beliefs in haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients: investigating differences in early and later years of current treatment. BMC Nephrol. 2008;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Goncalves F.A., Dalosso I.F., Borba J.M. Quality of life in chronic renal patients on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis: a comparative study in a referral service of Curitiba - PR. J Bras Nefrol. 2015;37(4):467–474. doi: 10.5935/0101-2800.20150074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Griva K., Kang A.W., Yu Z.L. Quality of life and emotional distress between patients on peritoneal dialysis versus community-based hemodialysis. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(1):57–66. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0431-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yang F., Griva K., Lau T. Health-related quality of life of Asian patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in Singapore. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(9):2163–2171. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-0964-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Günalay S., Oztürk Y.K., Akar H. The relationship between malnutrition and quality of life in haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2018;64(9):845–852. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.64.09.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ibrahim N., Chiew-Tong N.K., Desa A. Symptoms and health-related quality of life in patients with haemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Res J Med Sci. 2011;5(5):252–256. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ikonomou M., Skapinakis P., Balafa O. The impact of socioeconomic factors on quality of life of patients with chronic kidney disease in Greece. J Ren Care. 2015;41(4):239–246. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Iyasere O.U., Brown E.A., Johansson L. Quality of life and physical function in older patients on dialysis: a comparison of assisted peritoneal dialysis with hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(3):423–430. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01050115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kang S.H., Do J.Y., Lee S.Y. Effect of dialysis modality on frailty phenotype, disability, and health-related quality of life in maintenance dialysis patients. PLoS One. 2017;12(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kim J.Y., Kim B., Park K.S. Health-related quality of life with KDQOL-36 and its association with self-efficacy and treatment satisfaction in Korean dialysis patients. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(4):753–758. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0203-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kontodimopoulos N., Niakas D. An estimate of lifelong costs and QALYs in renal replacement therapy based on patients' life expectancy. Health Policy. 2008;86(1):85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kontodimopoulos N., Pappa E., Niakas D. Gender- and age-related benefit of renal replacement therapy on health-related quality of life. Scand J Caring Sci. 2009;23(4):721–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nakayama M., Ishida M., Ogihara M. Social functioning and socioeconomic changes after introduction of regular dialysis treatment and impact of dialysis modality: a multi-centre survey of Japanese patients. Nephrology (Carlton) 2015;20(8):523–530. doi: 10.1111/nep.12482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Neumann D., Lamprecht J., Robinski M. Social relationships and their impact on health-related outcomes in peritoneal versus haemodialysis patients: a prospective cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(7):1235–1244. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Okpechi I.G., Nthite T., Swanepoel C.R. Health-related quality of life in patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2013;24(3):519–526. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.111036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ören B., Enc N. Quality of life in chronic haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients in Turkey and related factors. Int J Nurs Pract. 2013;19(6):547–556. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ramos E.C., Santos I., Zanini R. Quality of life of chronic renal patients in peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis. J Bras Nefrol. 2015;37(3):297–305. doi: 10.5935/0101-2800.20150049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ruiz de Alegría-Fernández de Retana B., Basabe-Barañano N., Saracho-Rotaeche R. Coping mechanisms as a predictor for quality of life in patients on dialysis: a longitudinal and multi-centre study. Nefrologia. 2013;33(3):342–354. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2013.Feb.11771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tannor E.K., Archer E., Kapembwa K. Quality of life in patients on chronic dialysis in South Africa: a comparative mixed methods study. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12882-016-0425-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Theofilou P. Quality of life in patients undergoing hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis treatment. J Clin Med Res. 2011;3(3):132–138. doi: 10.4021/jocmr552w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Theofilou P. Association of insomnia symptoms with kidney disease quality of life reported by patients on maintenance dialysis. Psychol Health Med. 2013;18(1):70–78. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2012.674144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Turkmen K., Yazici R., Solak Y. Health-related quality of life, sleep quality, and depression in peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2012;16(2):198–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2011.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Watanabe Y., Ohno Y., Inoue T. Home hemodialysis and conventional in-center hemodialysis in Japan: a comparison of health-related quality of life. Hemodial Int. 2014;18(suppl 1):S32–S38. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wright L.S., Wilson L. Quality of life and self-efficacy in three dialysis modalities: incenter hemodialysis, home hemodialysis, and home peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Nurs J. 2015;42(5):463–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wu F., Cui L., Gao X. Quality of life in peritoneal and hemodialysis patients in China. Ren Fail. 2013;35(4):456–459. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2013.766573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ying S.C., Krishnan M. Interpretation of quality of life outcomes amongst end stage renal disease patients in selected hospitals of Malaysia. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2014;5(1):60–69. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Yongsiri S., Thammakumpee J., Prongnamchai S. The association between bioimpedance analysis and quality of life in pre-dialysis stage 5 chronic kidney disease, hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. J Med Assoc Thai. 2014;97(3):293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ware J.E. The Health Institute; Boston, MA: 1997. SF-36 Health Survey. Manual and Interpretation Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Liyanage T., Ninomiya T., Jha V. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Lancet. 2015;385(9981):1975–1982. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Moosa M.R., Maree J.D., Chirehwa M.T. Use of the 'accountability for reasonableness' approach to improve fairness in accessing dialysis in a middle-income country. PLoS One. 2016;11(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kilonzo K.G., Jones E.S.W., Okpechi I.G. Disparities in dialysis allocation: an audit from the new South Africa. PLoS One. 2017;12(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sakhuja V., Sud K. End-stage renal disease in India and Pakistan: burden of disease and management issues. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003;83:S115–S118. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s83.24.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Bello A.K., Alrukhaimi M., Ashuntantang G.E. Global overview of health systems oversight and financing for kidney care. Kidney Int Suppl. 2018;8(2):41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.kisu.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.van der Tol A., Lameire N., Morton R.L. An international analysis of dialysis services reimbursement. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(1):84–93. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08150718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Robinson B.M., Akizawa T., Jager K.J. Factors affecting outcomes in patients reaching end-stage kidney disease worldwide: differences in access to renal replacement therapy, modality use, and haemodialysis practices. Lancet. 2016;388(10041):294–306. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30448-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hood K., Robling M., Ingledew D. Mode of data elicitation, acquisition and response to surveys: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(27) doi: 10.3310/hta16270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Korevaar J.C., Feith G.W., Dekker F.W. Effect of starting with hemodialysis compared with peritoneal dialysis in patients new on dialysis treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Kidney Int. 2003;64:2222–2228. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Korevaar J.C., Jansen M.A.M., Merkus M.P. Quality of life in predialysis end-stage renal disease patients at the initiation of dialysis therapy. Perit Dial Int. 2000;20:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Manns B.J., Walsh M.W., Culleton B.F. Nocturnal hemodialysis does not improve overall measures of quality of life compared to conventional hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2009;75(5):542–549. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare [letter] BMJ. 2013;346:f167. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.van der Willik E.M., Meuleman Y., Prantl K. Patient-reported outcome measures: selection of a valid questionnaire for routine symptom assessment in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease - a four-phase mixed methods study. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):344. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1521-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1-S2; Table S1-S4.