Abstract

Microbiome sequence analyses have suggested that changes in gut bacterial composition are associated with autoimmune disease in humans and animal models. However, little is known of the mechanisms through which the gut microbiota influences autoimmune responses to distant tissues. Here, we evaluated systemic antibody responses against cultured human gut bacterial strains to determine whether observed patterns of anti-commensal antibody (ACAb) responses are associated with type 1 diabetes (T1D) in two cohorts of pediatric subjects. In the first, ACAb responses in sera collected from subjects within 6 months of T1D diagnosis were compared to age-matched healthy controls and also to recent onset Crohns’ Disease patients. ACAb responses against multiple bacterial species discriminated among these three groups. In the second cohort, we asked whether ACAb responses present before diagnosis were associated with later T1D development and with HLA genotype in subjects who were discordant for subsequent progression to diabetes. Serum IgG2 antibodies against Roseburia faecis and against a bacteria consortium, were associated with future T1D diagnosis in an HLA DR3/DR4-haplotype dependent manner. These analyses reveal associations between antibody responses to intestinal microbes and HLA-DR genotype, islet autoantibody specificity, and with a future diagnosis of T1D. Further, we present a platform to investigate anti-bacterial antibodies in biological fluids that is applicable to studies of autoimmune diseases and responses to therapeutic interventions.

One sentence summary:

Immune responses to gut bacteria display HLA-DR dependent associations with islet autoantibodies and future progression to T1D

Introduction

The increased incidences of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases in developed countries over the past 50 years suggests a causal role for environmental factors associated with improved hygiene and reduced microbial exposures in early life (1). Despite epidemiological support for this “hygiene hypothesis” (1), a mechanistic connection between the gut microbial ecosystem and autoimmunity that targets sites distant from the gut remains unclear. The composition and function of the gut microbial community (the microbiome) have been associated with risk of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, including type 1 diabetes (T1D), rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis (2–4). The complex interactions between the gut microbiome and the adjacent mucosal immune system are dysregulated in Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis, where inflammation targets the gastrointestinal tissue and compromises intestinal permeability. However, it is not clear whether immune responses to gut microbiota are associated with autoreactivity to host tissues outside the gut.

T1D results from autoimmune destruction, largely executed by T cells, of the insulin-producing pancreatic beta cells. Genetic factors, most notably the Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) class II haplotypes that govern antigenic peptide presentation to T cells, are key contributors to T1D risk (5). While the disease casn present at any age, it is most common in childhood, and has displayed earlier ages at onset over the past several decades (6, 7) again suggesting an impact of dynamic environmental factors. To address the increase in T1D incidence (8), recent studies have sought to define an association between gut microbiome composition and either disease onset or the appearance of islet autoantibodies a hallmark of pre-diabetes (4, 9, 10). A recurrent finding is that the fecal microbiota of subjects with multiple islet autoantibodies or new onset T1D displayed reduced taxonomic diversity, although associations with specific genera have varied between the studies (4, 10, 11).

We reasoned that an influence of the gut microbiome on islet autoimmunity would require immune responses detectable outside the gut mucosa. To address this idea, we have investigated patterns of antibody responses detectable in the blood against human fecal commensal (non-pathogenic) microbes. We hypothesized that the patterns of anti-commensal antibody (ACAb) responses might reveal interactions between HLA genotype and systemic immune response to gut microbes in the context of pancreatic autoimmunity.

We developed a platform to define and compare the titres and isotypes of ACAb responses, adapted from an assay used to detect antibodies against bacterial pathogens in immunized mice (12). We characterized ACAb response patterns in two pediatric cohorts: subjects with recent onset CD or T1D compared with healthy controls, and a prospective cohort of children at risk for, and prior to onset of T1D. We observed that patterns of ACAb responses distinguished CD from T1D patients and from healthy controls. ACAb responses against specific commensals measured before T1D diagnosis differentiated subjects with islet autoimmunity and healthy controls in HLA haplotype-dependent manner. Moreover, we identify an HLA-dependent association of ACAb against specific commensals with the specificities of anti-islet autoantibodies before diabetes development. Our results indicate that distinct HLA genotype-associated immune response patterns against gut commensals accompany pre-diabetes and we provide an approach to evaluate the role of the gut microbiome in immune-mediated diseases affecting extra-mucosal tissues.

Results

Anti-commensal bacterial antibodies (ACAb) have been reported in mice harboring mutations in innate immune sensing pathways (13) and in adults with HIV infection or inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC); (14)). While HIV patient and healthy control (HC) sera displayed equivalent levels of antibody binding to gut and skin-derived bacteria, the CD and UC patients displayed elevated antibody responses to three bacterial isolates, suggesting that gut barrier compromise results in heightened immune priming to intestinal bacteria. Here, we evaluated the titres and isotypes of ACAb to ask whether these patterns are associated with T1D, an autoimmune disease where the target tissue is distant from the gut, and which is not characterized by clinical enteropathy.

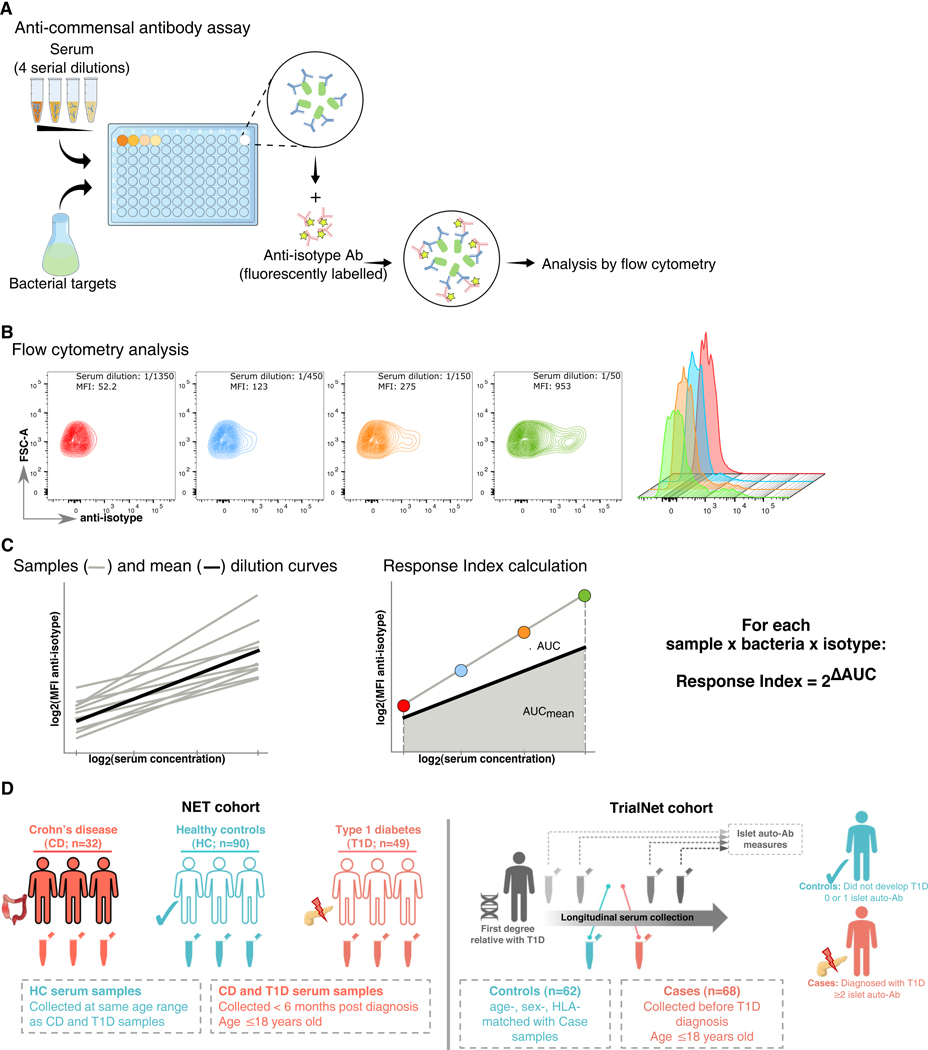

We measured ACAb responses against a panel of bacterial strain pools representative of genera found in healthy human gut microbiota (Supp. Table 1). Given the extensive strain-level genetic variation in human gut bacterial species (15), multiple strains were used for each species to maximize potential antigenic diversity. Also included was a previously reported consortium of 32 commensal bacterial strains (MET-2) isolated from healthy donor stool. MET-2 forms a diverse ecosystem in vitro with a metabolic output approximating that of the host fecal ecosystem (16) (Supp. Table 1). Four serial dilutions (1/50 – 1/1350) of each serum sample were incubated with a defined number of each strain of cultured bacteria, incubated with fluorophore-labelled second stage antibodies to detect total human Ig, IgA and/or IgG antibodies, and evaluated by flow cytometry analysis. Response indices were computed for each sample, for each antibody isotype and each bacterial target (Figure 1; Materials and Methods).

Figure 1: Overview of anti-commensal antibody assay and pediatric cohorts in this study.

(A) Schematic representation of the anti-commensal antibody assay. In a first step, bacteria targets of a specific strain pool are incubated with 4 serial dilutions of the serum sample allowing serum antibodies to bind bacteria surface antigens. Next fluorescently-labelled, secondary anti-isotype antibodies (anti-IgA, IgG1, IgG2 and total Ig) are added allowing the visualization of the bacteria through flow cytometry. (B) An example of the signal measured by flow cytometry for one bacteria pool and four serial dilutions of a serum sample. The first four panels show contour plots of the anti-isotype intensity vs forward scatter parameter. The last panel shows a histogram overlay of the anti-isotype signal intensities. (C) Schematic representation of the Response Index calculation. For every serum sample, bacteria strain pool and isotype the dilution curve of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) vs dilution factor are generated on a log-log scale (left panel, grey lines). The mean dilution curve is generated using the average MFI values for all serum samples (left panel, black line). For every sample the difference between its dilution AUC and the mean dilution AUC is calculated (ΔAUC, right panel). The resulting Response Index is calculated as 2ΔAUC. (D) Schematic representation of the NET and TrialNet cohort subjects analyzed in this study.

Pediatric serum samples (age ≤18y) from the NET study were collected from recent onset Crohn’s disease patients (n=32), recent onset T1D (n=49) patients and age-matched healthy controls (n=90). Serum samples were also obtained from TrialNet subjects ≤18 years of age. Samples defined as “Cases” (n=68) were collected before T1D diagnosis from individuals with ≥2 positive islet autoantibodies who developed T1D during the study follow-up. Samples defined as “Controls” (n=62) were collected from age-, sex- and HLA-matched individuals who did not receive a T1D diagnosis within the follow-up period.

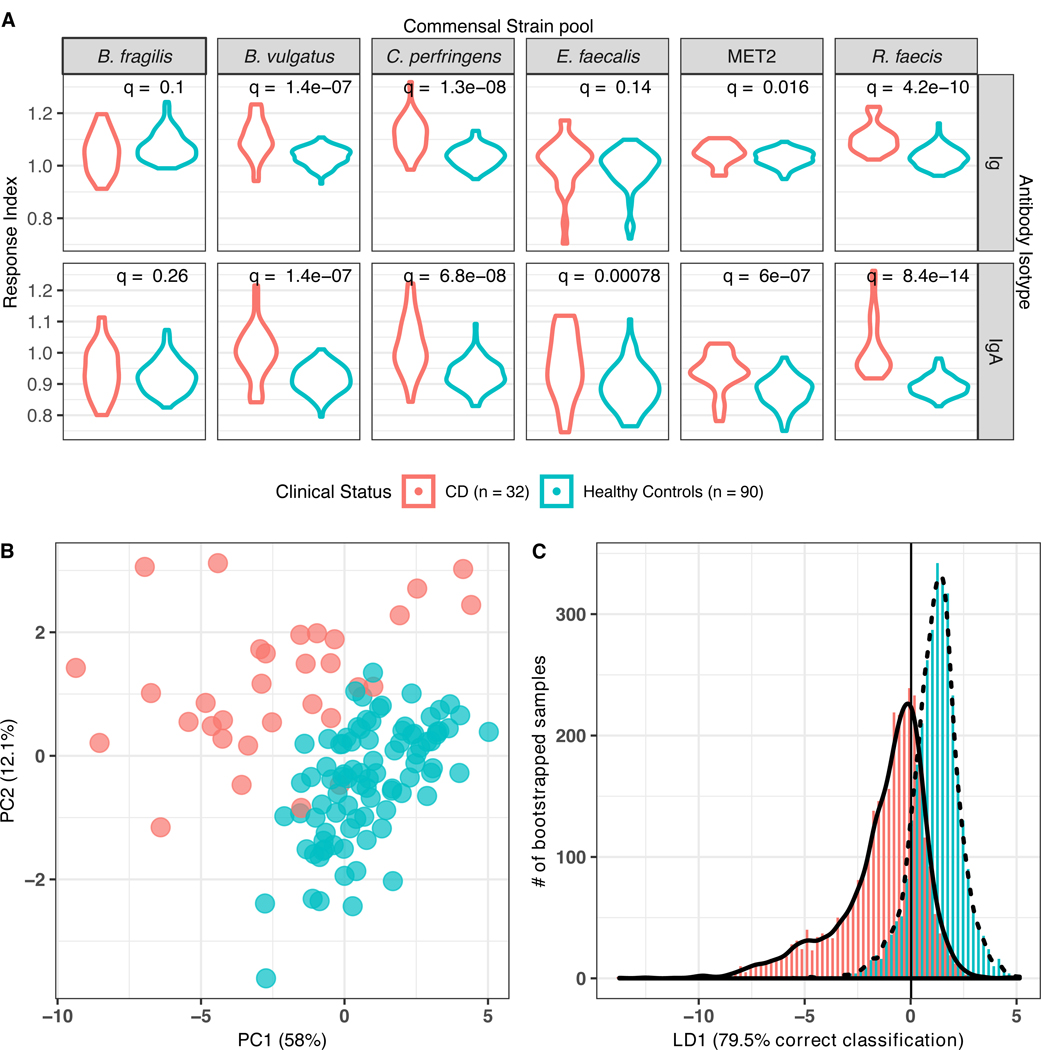

Distinct anti-commensal antibody responses in Crohn’s patients and healthy controls

Pediatric serum samples (age ≤18y) from a clinical autoimmunity study (“NET” cohort (17)) were selected to compare ACAb responses in the serum of recent onset T1D patients and recent onset CD patients with age-matched healthy controls (HC) (Figure 1D and Supp. Figure 1). T1D or CD case serum samples were collected within six months after diagnosis and none of these subjects had been treated with immunosuppressive drugs during this period. Control samples were collected from children with no clinical diagnosis of disease within the study follow-up period (Table 1a). First, we compared ACAb responses in sera from recently diagnosed CD patients and HC from the NET study cohort (Figure 2). We reasoned that the heightened systemic exposure to gut bacteria in CD patients (14) would allow us to validate measurement of ACAb responses against human gut commensals in pediatric serum samples. Indeed, elevated total Ig and IgA ACAb responses to B. vulgatus, C. perfringens, MET-2 and R. faecis; and IgA against E. faecalis were observed in CD patients compared to HC (Figure 2a). To visualize the variation in ACAb responses by all the samples to each bacterial target, we performed an unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA) (Figure 2b). ACAb responses from CD patient and healthy control samples clustered separately by two PC that captured 70% of the variance.

Table 1a:

Characteristics of NET cohort subjects

| Crohn’s Disease (n=32) | Type 1 Diabetes (n=49) | Controls (n=90) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (% males) | n=17 (53%) | n=31 (62%) | n=30 (33%) |

| Age at diagnosis (years; mean±stdev) | 12.30 (±2.96) | 10.68 (±3.95) | N/A |

| Age at ACAb test (years; mean±stdev) | 12.96 (±3.03) | 11.08 (±3.98) | 14.91 (±2.10) |

| Time between ACAb test and diagnosis (days; mean±stdev) | 241 (±480) | 135 (±94) | N/A |

Figure 2: Anti-commensal antibody responses in Crohn’s disease (CD; n=32) and healthy control (n=90) serum samples from NET pediatric subjects (CD •/ Healthy Controls •).

(A) Distribution of anti-commensal antibody responses, separated by six commensal strain pools (columns, top) and antibody isotype total Ig or IgA (rows, right) displayed as violin plots. Width of plotted area indicates the density distribution of the responses. q = Wilcoxon log-rank test FDR-adjusted q values. (B) Principal components analysis of anti-commensal antibody responses of all subjects to all bacterial targets (70.1% of total variance explained). (C) Bootstrapped-rarefied two-fold cross-validation of linear discriminant analysis of anti-commensal antibody responses by CD patients and healthy controls. Y axis displays the number of bootstrapped serum samples in the analysis, of which 78.8%% were correctly classified.

A linear discriminant analysis (LDA) was conducted to determine if these ACAb responses could discriminate CD from healthy control samples (Figure 2c). We used variance inflation factor (VIF)-based (VIF threshold = 10) variable selection to remove responses that could be represented by combinations of other (collinear) responses, and then performed a LDA with 100x repeated 2-fold cross-validation on the remaining variables (Materials and Methods). The resulting LD values correctly classified 78.8% (95% CI: 70.3% – 87.5%) of all randomly selected samples, suggesting that the VIF-selected set of ACAb responses could discriminate between the majority of CD and healthy control samples.

Since a substantial proportion of NET subjects were in or beyond the pubertal period when the serum samples were obtained, we tested for effects of sex using linear regression models with sex and clinical status as covariates. Sex differences were observed for IgA responses against Bact.fragilis, C.perfringes, E.fecalis and MET2 as well as total Ig responses against C.perfringes. For IgA responses against B.vulgatus and E.fecalis we found a significant interaction between sex and status (ANOVA for interaction coefficients FDR-adjusted q <0.12). ACAb responses were higher in female compared to male CD cases but this pattern was not observed in healthy control subjects (Supp. Figure 2).

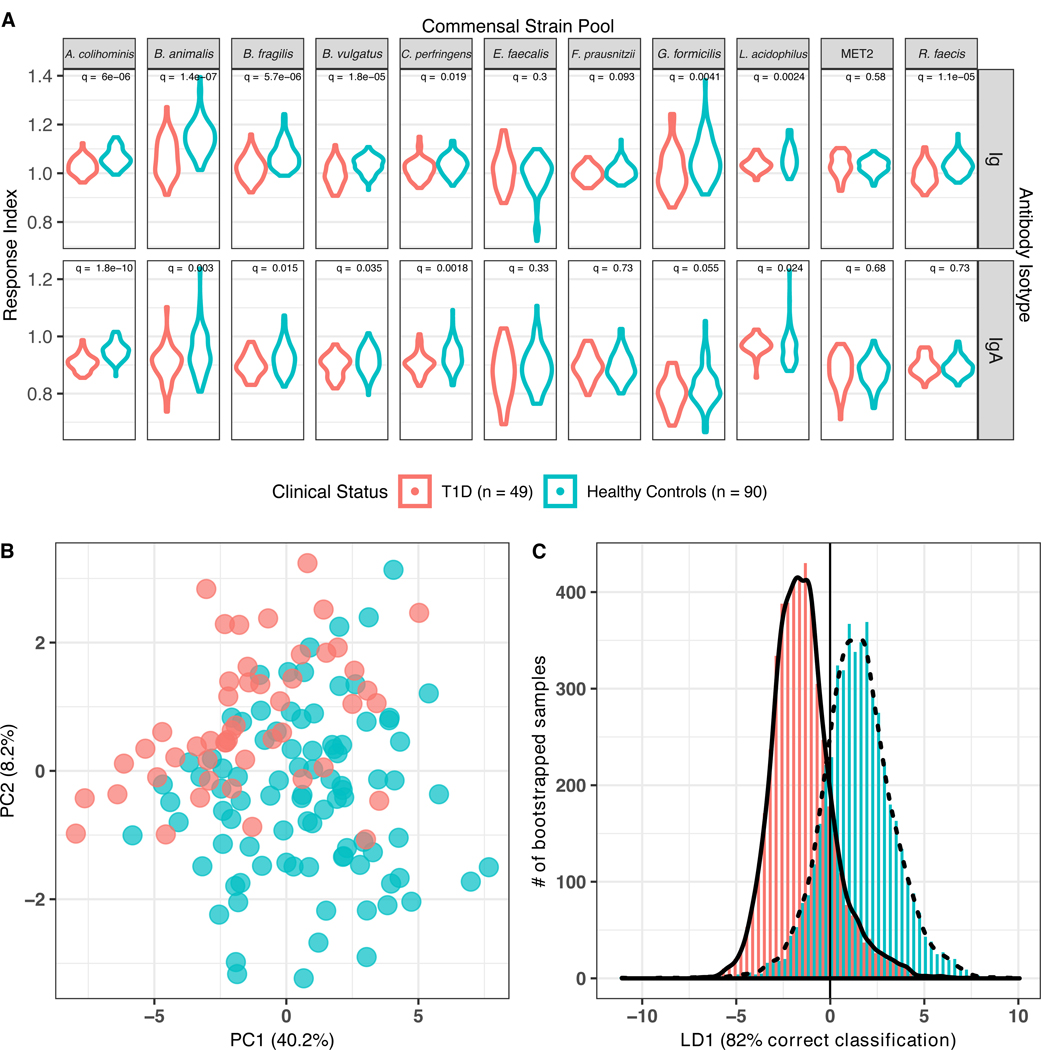

Anti-commensal antibody responses distinguish T1D patients from control subjects

Multiple studies have reported correlations between the taxonomic composition and inferred functional capacity of host microbiota and autoimmune diseases in human subjects. However, we lack an understanding of the mechanisms that link these mucosal microbes with systemic immune responses and autoimmune targeting of distant tissues. In contrast to CD, the target of many autoimmune diseases is outside the gut. To examine immune responses to gut commensal bacteria in this setting, we examined serum samples from pediatric subjects in the NET study that had been recently diagnosed with T1D compared to age-matched HC (Figure 1D). To enhance the scope of the analysis, we added bacterial species belonging to genera reported to be differentially abundant in children with ≥2 islet autoantibodies compared to autoantibody-negative age, sex and HLA-matched children or with new onset T1D (9, 10). Recent onset T1D patient and healthy control sera displayed differences in both Ig and IgA ACAb responses against A. colihominis, Bif. animalis, Bact. fragilis, B. vulgatus, C. perfringens and L. acidophilus; and total Ig against G. formicilis and R. faecis (Figure 3a). Unsupervised PCA of all ACAb responses also displayed these differences between T1D and HC subjects (Figure 3b) suggesting that the patterns of ACAb responses differed between these two groups of subjects.

Figure 3: Anti-commensal antibody response in type 1 diabetes (T1D; n=49) and healthy control (n=90) serum samples from NET pediatric subjects. (T1D •/ Healthy Controls •).

(A) Distribution of anti-commensal antibody responses, separated by 11 commensal strain pools (columns, top), antibody isotype total Ig and IgA (rows, right). Width of plotted area indicates the density distribution of the responses. q = Wilcoxon log-rank test FDR-adjusted q values. (B) Principal components analysis of anti-commensal antibody responses of all subjects to all bacterial targets (49% of total variance explained). (C) Bootstrapped-rarefied two-fold cross-validation of linear discriminant analysis of anti-commensal antibody responses by T1D patients and healthy controls. Y axis displays the number of bootstrapped serum samples in the analysis, of which 82.3% were correctly classified.

LDA was performed to determine if these ACAb responses could discriminate between T1D and healthy control samples. Cross-validation with a set of VIF-selected responses correctly classified 82.0% (95% CI: 74.5 – 87.8 %; Figure 3c). Thus, ACAb responses against these fecal commensal species distinguished HC from age-matched, recent onset T1D patients. In contrast to the ACAb responses in the CD patients which were elevated compared to HC, ACAb responses in T1D patients were not consistently greater than those observed in HC; indeed, we observed comparatively lower total Ig and IgA responses to A. colihominis, Bif. animalis, Bact. fragilis, B. vulgatus, and C. perfringens in T1D cases compared to HC. These data suggest that pediatric patients with extra-intestinal autoimmunity display distinct patterns of ACAb responses compared to age matched HC.

We employed a linear regression to determine whether there were sex effects on ACAb responses between HC and T1D cases (Supp. Figure 3). In contrast to the comparison between CD patients and HC, we found no significant interaction effects between sex and clinical status, however sex displayed a significant additive effect on the IgA responses against Bif. animalis, Bact.fragilis, F.prausnitzii, G.formicilis and MET-2, as well as total Ig responses against Bif. animalis, B.vulgatus and C.perfringens (Supp. Figure 3). Taken together with the CD subject data (Supp. Figure 2), these results indicate the need for ongoing stratification by sex in analyses of human anti-microbial immune responses.

Anti-commensal antibody response patterns in pre-diabetic subjects

We considered the possibility that the distinct ACAb responses observed in the NET cohort of recent onset T1D patients may have been impacted by the metabolic abnormalities, dietary modifications and exogenous insulin treatment that follow disease diagnosis. Therefore, we next investigated pre-diabetic subjects with normal blood sugars but who were seropositive for islet autoantibodies predictive of autoimmune progression. Serum samples were obtained from participants in the TrialNet Pathways to Prevention study (18), a well-characterized, prospectively collected, cohort of subjects before T1D onset (Figure 1D). Serum samples were obtained from TrialNet subjects ≤18 years of age (Table 1b, Supp. Figure 4). Samples defined as “cases” (n=68) had been collected 175–712 days (mean=344 days) prior to T1D diagnosis (Supp. Figure 5a) from individuals with ≥2 positive islet autoantibodies. Samples from “controls” (n=62) were age-, sex- and HLA-haplotype matched to the cases, and collected from individuals who did not receive a T1D diagnosis within the follow-up period (2646 ± 1051 days; Supp. Fig. 5b, c), and who displayed either zero or one positive islet autoantibodies at the time of blood sampling. ACAb analyses of the TrialNet subjects included IgG1, IgG2 and IgA isotype classes. Thirty-two ACAb responses (eight bacterial targets x four isotypes) were evaluated in serum samples from 68 case and 62 matched control subjects (Supp Figure 6a).

Table 1b:

Characteristics of TrialNet cohort subjects

| Cases (n=68) | Controls (n=62) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (% males) | n=36 (53%) | n=32 (52%) |

| Age at T1D diagnosis (years; mean±stdev) | 11.61 (±3.76) | N/A |

| Age at ACAb test (years; mean±stdev) | 10.67 (±3.82) | 10.92 (±3.65) |

| Time between ACAb test and diagnosis (days; mean±stdev) | 344 (±120) | N/A |

| Follow-up time (days; mean±stdev) | 1045 (±711) | 2646 (±1051) |

| HLA DR3 positive / DR4 negative | n=20 (29%) | n=18 (29%) |

| HLA DR3 negative / DR4 positive | n=22 (32%) | n=21 (34%) |

| HLA DR3 & DR4 positive | n=12 (18%) | n=10 (16%) |

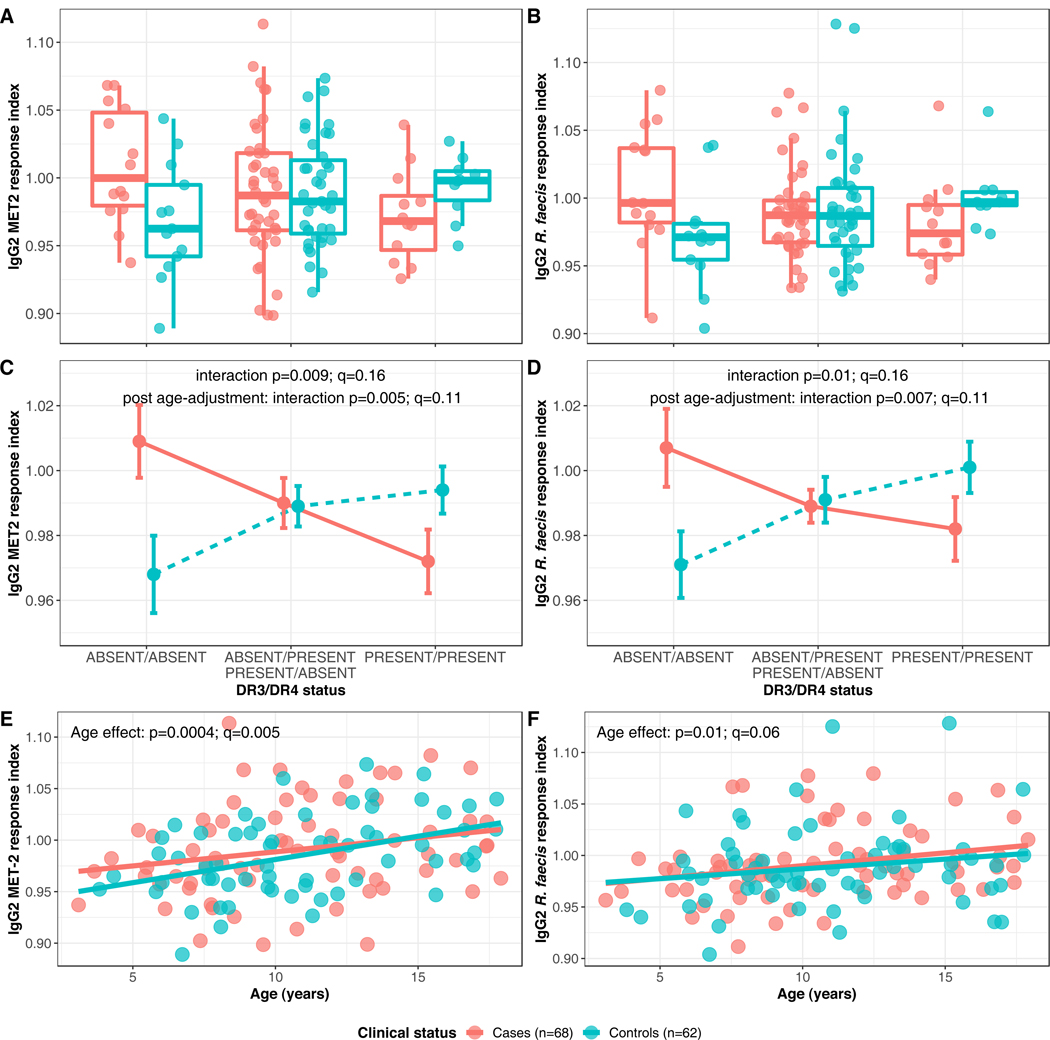

HLA-dependent association of ACAb responses with future T1D diagnosis

The HLA locus accounts for 30–50% of the genetic risk of type 1 diabetes, with HLA class II haplotypes DR3-DQ2 and DR4-DQ8 showing the greatest association (19, 20). Despite the massive effect size of HLA class II genotypes in T1D risk and reported associations between gut microbe composition and disease (4, 9, 10), there is no evidence for HLA association with human gut microbial composition. The TrialNet metadata included HLA genotype allowing us to address the possibility that ACAb responses display associations with HLA haplotypes and with future T1D onset. First, we evaluated ACAb responses without inclusion of HLA haplotype as a variable and observed no association with a future diagnosis of T1D (Supp. Figure 6a). In addition, neither PCA (Supp Figure 6b) nor LDA (Supp Figure 6c) revealed differential ACAb patterns between pre-diabetic case and control samples. Thus, we next analyzed the ACAb responses using HLA DR haplotypes as a covariate.

A multivariate linear regression analysis including clinical status and HLA haplotypes as covariates revealed robust associations of certain ACAb responses with a future T1D diagnosis in an HLA class II-dependent manner (Figure 4a, b; comparisons for all ACAb responses shown in Supp. Figure 7). The interaction between a future T1D diagnosis and the presence of high-risk haplotypes DR3 and DR4 was associated with IgG2 ACAb responses against MET-2 and R. faecis (Figure 4c, d; ANOVA p=0.009 and 0.01, respectively; q=0.16). Samples from cases lacking both DR3 and DR4 displayed higher MET-2 and R. faecis responses, those with either DR3 or DR4 had intermediate responses, and cases with both DR3/DR4 haplotypes had lowest responses (Figure 4c, d). In contrast, samples from controls displayed the opposite response pattern to both bacterial groups. Total Ig responses against the same bacterial species also showed a significant HLA-DR3 and DR4-dependent association with clinical status (Supp. Figure 8 a–d). Ig and IgG2 responses against the same bacterial target were highly correlated (Supp. Figure 9a, b) suggesting that IgG2 responses were the major signals captured against the bacterial targets, although correlations between total Ig, and IgA and IgG1 suggest that IgA and IgG1 responses may also contribute (Supp. Figure 9 c, d, e, f).

Figure 4: Anti-commensal antibody response indices displaying interaction effects between HLA haplotype and clinical status in TrialNet samples (Cases •/ Controls •).

(A) Box-and-whiskers plot of anti-MET-2 IgG2 response indices (Y axis), segregated by HLA haplotype (X axis). (B) Box-and-whiskers plots of anti-R.faecis IgG2 response indices (Y axis), segregated by HLA haplotype (X axis). (C) Interaction plot of anti-MET-2 IgG2 response indices. (D) Interaction plot of anti-R.faecis IgG2 response indices. (E) Linear regression of anti-MET-2 IgG2 response indices by age. (F) Linear regression of anti-R.faecis IgG2 response indices by age.

(A) and (B) Horizontal line represents the median and rectangle represents the inter-quartile range (25th - 75th percentile). Whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values which were not outliers. Outliers were defined as points outside of median±1.5* inter-quartile range.

(C) and (D) data are shown as mean ± standard error, and p-value and q-value for the interaction effect significance are shown for the responses without (IgG2 MET-2: p=0.009, q=0.16; IgG2 R.faecis p=0.01, q=0.16) and with (IgG2 MET-2: p=0.005, q=0.11; IgG2 R.faecis p=0.007, q=0.11) age adjustment.

(E) and (F) Regression lines for cases and controls as well as age effect-associated p-values and q-values are shown (IgG2 MET-2: p=0.0004, q=0.005; IgG2 R.faecis p=0.01, q=0.06).

Longitudinal microbiome analyses in children at risk for T1D have revealed striking age-dependent, developmental patterns in microbiota diversity, composition and function (21–23). These findings, together with the wide age range in the TrialNet subjects (Supp Fig. 4) prompted us to investigate whether their antibody responses against gut commensals were also age-dependent. IgG2 and total Ig responses against MET-2 and IgG2 responses against R.faecis were correlated with age (ANOVA p<0.02, q<0.07; Figure 4 e,f and Supp. Fig 8 e,f). Moreover, when the analysis was adjusted for the age effect, the HLA-dependent associations with future T1D diagnosis of IgG2 and total Ig antibodies against MET-2 and R.faecis reported above were stronger (ANOVA p-values pre- and post-age adjustment shown in Figure 4 c,d and Supp Fig 8 c,d). Therefore the HLA-dependent association of ACAb responses with T1D development were robust to age variation in the TrialNet cohort.

Thus, inclusion of HLA haplotypes in the analysis was critical to reveal associations of ACAb responses and T1D, and these associations were strengthened by analysis that removed age effects. The HLA dependency of the relationship between ACAb responses and future T1D development suggests a critical role of this genetic risk factor in modifying the interactions between immune responses to gut microbes and diabetes development.

Association of anti-commensal antibody responses with islet autoantibody specificity

Assessment of islet autoantibody titers is the best available biomarker for predicting the development of T1D in genetically susceptible individuals (24, 25). Moreover, islet autoantibody antigen specificity displays HLA class II haplotype dependence. Anti-GAD65 autoantibodies (GADA) have been associated with DR3 and anti-insulin autoantibodies (IAA) and islet cell autoantibodies (ICA) with DR4 haplotype (26, 27). We tested these associations in the TrialNet cases using longitudinal measures of GADA, IAA, tyrosine phosphatase-protein IA-2 autoantibodies (IA2A) and ICA. Recapitulating previous studies, we found that DR3 positive individuals had a higher frequency of positive GADA measures before T1D diagnosis (Supp. Figure 10a, χ2=15.73, p=5×10−4), and DR4 positive individuals displayed a higher frequency of positive IAA measures compared to alternative DR3/DR4 genotypes (Supp. Figure 10b, χ2=6.0, p =0.014). Thus, HLA class II haplotype associations with islet autoantibody specificity in this TrialNet cohort accorded with those previously reported in independent groups of subjects (26, 27).

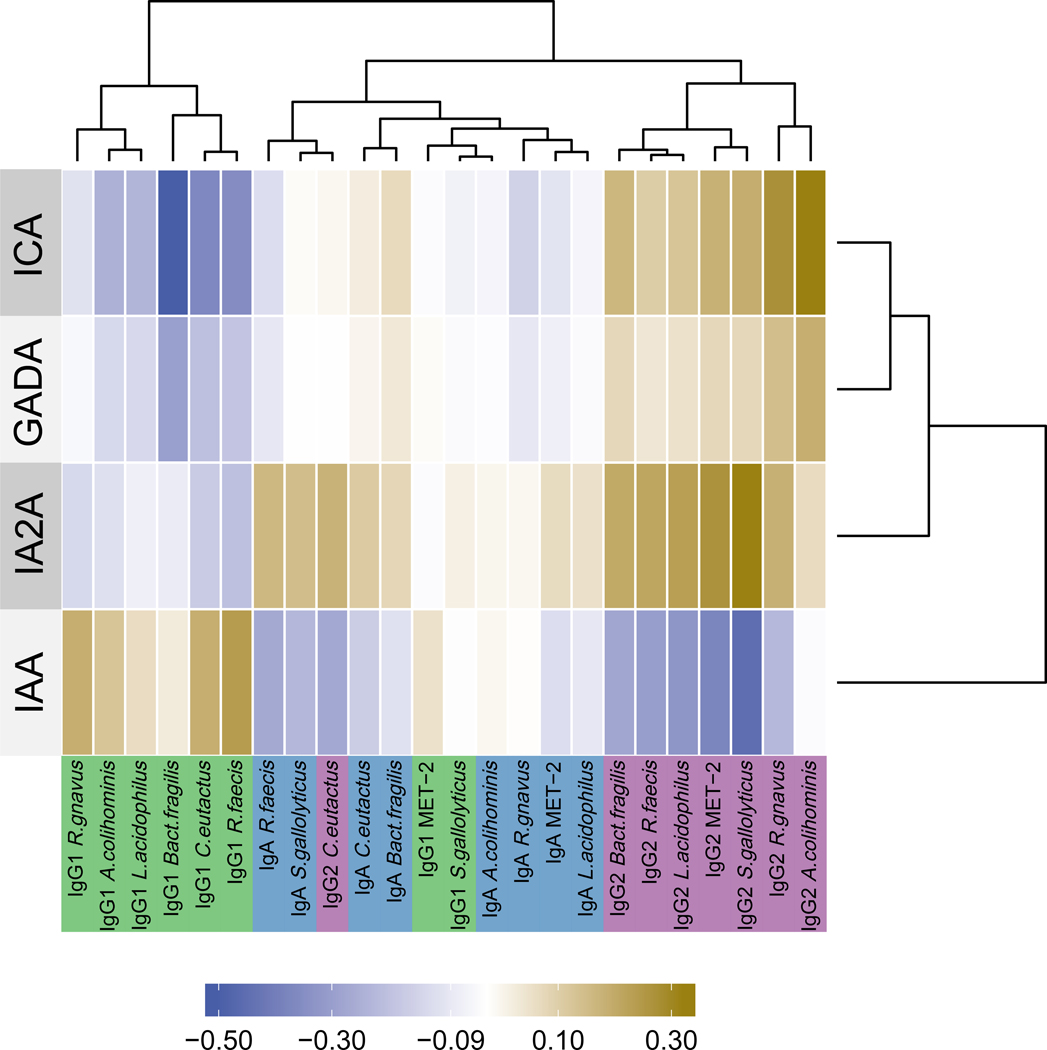

Given the observed HLA-dependent associations of some ACAb responses with future T1D diagnosis (Figure 4) and the well-established association of autoantibody seroconversion with progression to T1D, we investigated the relationship between ACAb responses and islet autoantibody seroconversion. A Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) between the ACAb responses and autoantibody specificities revealed relationships between these two datasets (see Methods for details) visualized in a heatmap (Figure 5). The key finding was that the isotype of ACAb responses clustered with islet autoantibody specificity. Specifically, IgG1 ACAb responses were negatively correlated with ICA, and IgG2 ACAb responses were positively correlated with IA2A and negatively correlated with IAA in seroconverted individuals. In contrast to these IgG responses, IgA isotype ACAb did not display strong correlations with any islet autoantibody specificity in these pre-diabetic individuals.

Figure 5: Correlations between isotype-specific anti-commensal antibody responses and islet auto-antibody positive status in TrialNet case samples (n=68).

Correlations between isotype-specific ACAb responses (columns, bottom) and islet auto-antibody positive status (rows, left) are shown in heatmap colors. ACAb responses and IABs were each clustered by similarity by hierarchical clustering (dendrograms top and right, respectively). ACAb isotypes: IgA •/ IgG1•/ IgG2 •.

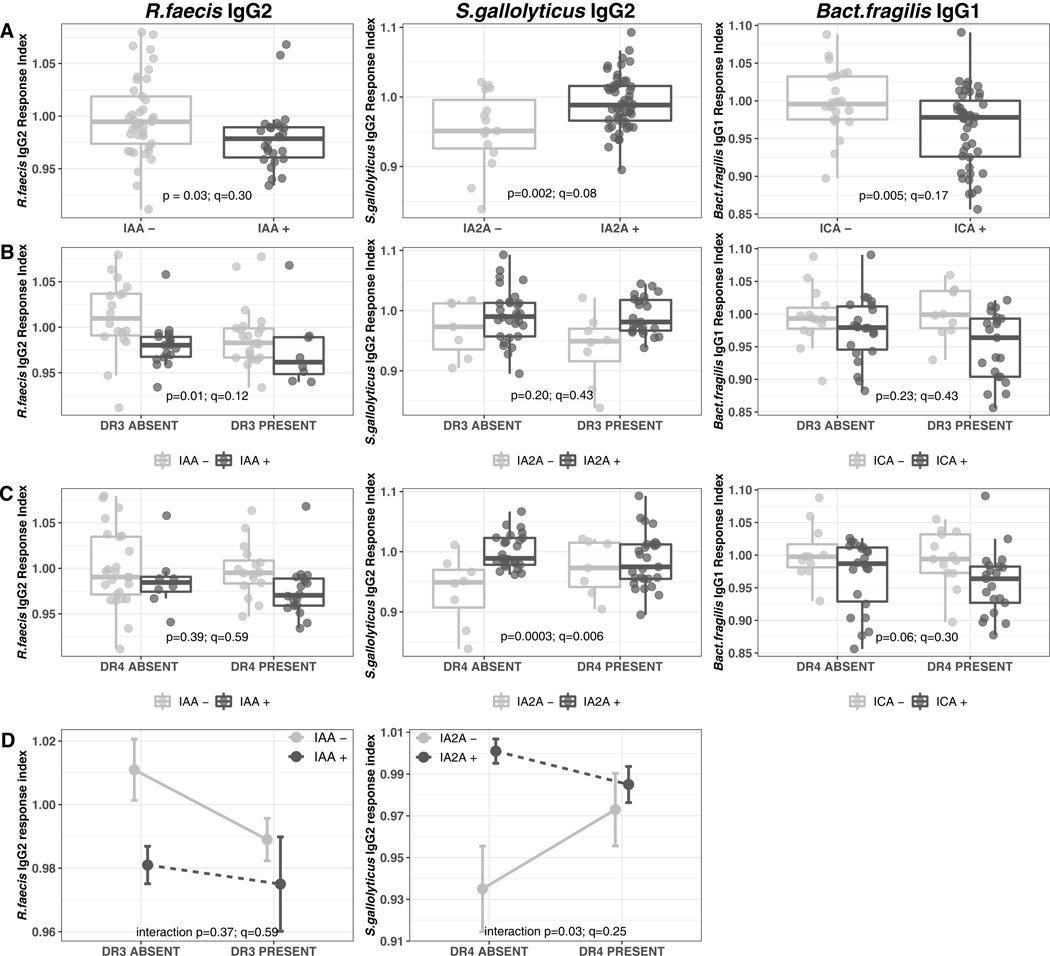

The CCA revealed the correlations between ACAb isotype responses and autoantibody specificities (Figure 5). Our data (Supp Figure 10) and previous studies (26, 27) demonstrate associations between HLA haplotypes and islet autoantibody specificity. Therefore, we tested the HLA dependence of the associations between islet autoantibody specificities and ACAb responses. Pairwise regression models were used to identify the main effects of autoantibody specificity on ACAb responses. We identified six ACAb-autoantibody associations with a nominal p-value<0.05 and q<0.5 (Figure 6a and Supp. Figure 11a) which were further analyzed for dependency on HLA DR3 or DR4 haplotypes. Three of these associations did not reach statistical significance after correction for multiple tests (Supp. Figure 11). For three other ACAb we observed significant associations with islet autoantibody specificity (q<0.2, Figure 6). The association between IAA and IgG2 against R.faecis, and that between IA2A and IgG2 against S.gallolyticus were both more robust with inclusion of HLA haplotype. Thus the presence of DR3 and IAA specificity displayed an additive effect on the R.faecis IgG2 response (ANOVA p=0.01, q=0.12, Figure 6b). Similarly the association between IA2A specificity and IgG2 against S.gallolyticus were only observed in the absence of DR4 (ANOVA p=0.0003; q=0.006; Figure 6c). The latter observation indicates that the relationship between the islet autoantibody specificity and this ACAb response is modulated by HLA DR4 haplotype (interaction ANOVA p=0.03; q=0.25, Figure 6d). In contrast, the relationship between ICA specific autoantibodies and the Bact.fragilis IgG1 response (ANOVA p=0.005; q=0.17; Figure 6a) was independent of HLA DR (ANOVA p>0.06, Figure 6b and c). Thus as presented above for association of ACAb responses with future progression to T1D (Figure 4), the relationship between certain ACAb responses and islet autoantibody specificities was also HLA DR haplotype-dependent.

Figure 6: Anti-commensal antibody responses displaying an association with islet auto-antibody positive status in TrialNet case samples (n=68).

(A) Box-and-whiskers plots of isotype-specific anti-commensal response indices (Y axis), separated by auto-antibody statuses (X axis) (B) Box-and-whiskers plot of the isotype-specific anti-commensal response indices (Y axis), auto-antibody status and HLA DR3 genotype status. (X axis) (C) Box-and-whiskers plot of the isotype-specific anti-commensal response indices (Y axis), auto-antibody status and HLA DR4 genotype status. (X axis) (D) Interaction plots for isotype-specific anti-commensal response indices with significant HLA DR3/DR4 genotype status additive effect.

(A-C) The horizontal line represents the median and the rectangle represents the inter-quartile range (25th -75th percentile). The whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values which were not outliers. Outliers are defined as points outside of median±1.5* inter-quartile range. (A) P-values were generated by a linear regression model with only the autoantibody positivity as the explanatory variable and indicate the significance of the autoantibody main effect. (B, C) P-values were generated by a linear regression model with autoantibody positivity and DR3/DR4 genotype as the explanatory variables and indicate the significance of the autoantibody effect in the HLA-adjusted model. (D) Data is shown as mean ± standard error. P-values were generated by ANOVA comparing the additive linear model to the model with an interaction term. (See Methods).

Discussion

The rapid increase in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases in developed countries over the last 60 years (28) has focused attention on environmental factors, and their potential impact on the gut microbiome, to explain this epidemiology. In T1D, 16S rRNA gene and shotgun metagenomic sequencing studies, have investigated the composition and functionality of gut microbiota and its relationship to anti-islet autoimmunity in human cohorts (4, 21, 29–33). One recurrent finding from these studies is lower diversity in bacterial composition in children who became diabetic compared to those who did not, but these differences were not evident in islet autoantibody seroconverters who remained diabetes-free (4). However, microbiome sequence analyses have not produced a consensus on the relationship between abundance of specific bacteria taxa and either future disease development or islet autoantibody seroconversion. A recent longitudinal analysis of n=10,903 fecal metagenomes from n=783 children in The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study who progressed to autoantibody sero-conversion or T1D, with matched controls, reported that “...most of the taxonomic and functional signals we detected in case-control comparisons were modest in effect size and statistical significance” (22). Given the size and analytical scope of this study, the results demonstrate that heterogeneity in microbiome composition presents a significant challenge to resolving patterns that are associated with immune responses against a distant target tissue. Here we have queried immune responses to intestinal bacteria in pediatric subjects at risk for T1D and provide evidence that, in contrast to microbiome composition, these responses are associated with the development of type 1 diabetes and the specificity of anti-islet autoimmunity in an HLA genotype dependent manner.

Compared to age-matched healthy controls, we found the titers of serum IgA and total Ig against specific commensals were higher in recent onset pediatric CD patients (Figure 1a), consistent with previous reports (34–36). These heightened anti-commensal immune responses likely reflected impaired intestinal barrier function observed in CD (37, 38), which allowed translocation of gut bacterial antigens and subsequent priming of B cells in extra-mucosal lymphoid organs. In contrast, the majority of human studies suggest that in T1D, gut barrier disruption can be detected after, but not prior to, disease onset (39–41). We found that levels of serum total Ig and IgA against the majority of commensal bacteria tested were lower in NET subjects recently diagnosed with T1D compared to healthy matched controls (Figure 2a). A longitudinal study of children at risk for allergic diseases reported that decreased IgG sero-reactivity to a group of commensal antigens during infancy was associated with allergy development later in life (42), suggesting a protective role of adaptive immune response to the microbiota against immune-mediated diseases in susceptible individuals. The decreased ACAb titers in new onset T1D patients indicate that the disease may be inversely correlated with systemic immune stimulation by gut commensals. Consistent with this idea, fecal microbiome analysis of infants with high risk HLA haplotypes for T1D has suggested that sources of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) during early life distinguished Finnish and Estonian subjects from those in a neighboring region of Russia (21). Relative to the former two countries, this Russian region has a far lower prevalence of T1D and allergic disease. Perhaps early life exposure to some microbial components protects from autoimmunity. Our analyses discriminated both CD and T1D cases from healthy controls (Figure 1b, c and Figure 2b, c) demonstrating that anti-commensal response patterns reflect the distinct phenotypes of the two diseases.

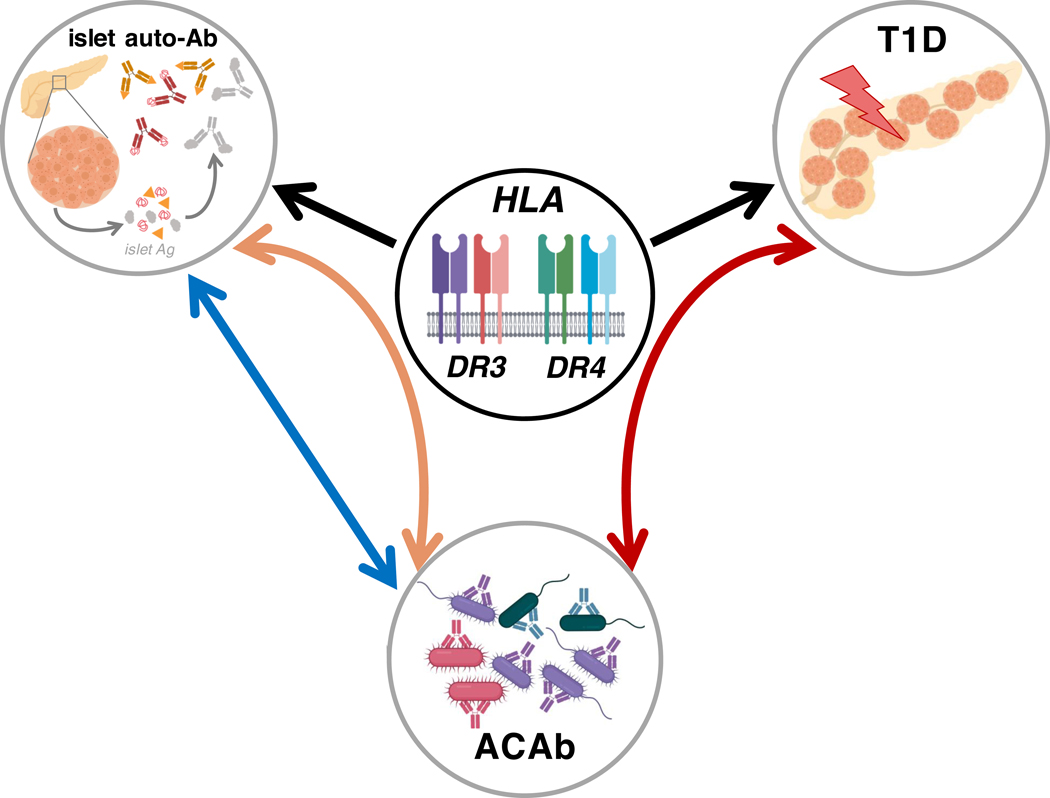

In the NET subjects with T1D, disease related metabolic abnormalities may influence immune function, specifically antibody responses to commensal bacteria. To mitigate this possibility, we examined ACAb responses in serum samples collected months before diagnosis in the independent TrialNet prospective cohort. While ACAb response patterns discriminated recent onset T1D patients from healthy control NET subjects, the pre-diabetic TrialNet cases were indistinguishable from matched controls (Supp. Figure 6). However, inclusion of the subjects’ HLA genotype in the analysis revealed robust association between ACAb responses and a future T1D diagnosis (Figure 4). The observed HLA-DR dependence of ACAb responses identified a relationship between immune responses to gut bacteria and the most impactful inherited risk factor for this disease (Figure. 7).

Figure 7: Graphical summary of HLA haplotype-dependent associations of anti-commensal antibody responses with islet autoimmunity and future T1D diagnosis.

HLA class II haplotypes are the strongest genetic determinants of T1D risk and with islet autoantibody specificities (black arrows). In a pediatric cohort of at-risk subjects, we uncovered HLA DR3/DR4-dependent associations between systemic anti-commensal antibodies (ACAb; lower circle) and future T1D diagnosis (right curved red arrow, upper right circle). In the same subjects, we found that islet autoantibody specificities (upper left circle) were associated with ACAb responses both in an HLA-dependent (left curved orange arrow) and HLA-independent (left straight blue arrow) manner.

Specific ACAb responses displayed a DR3/DR4-dependent association with disease progression in highest genetic risk TrialNet subjects carrying both DR3 and DR4 haplotypes. These subjects displayed lower IgG2 and total Ig responses to R.faecis and the MET-2 consortium compared to controls that did not become diabetic, whereas the reverse pattern existed in case subjects that lacked both DR3 and DR4 (Figure 4 and Supp. Figure 8). These results suggested that HLA-DR genotype strongly impacts the relationship between ACAb responses and islet-specific autoimmunity before disease diagnosis (Figure 7, red arrow).

Previous studies have shown that in addition to T1D risk, the specificity of islet autoantibodies is also associated with DR3 and DR4 haplotypes (26, 27), findings we confirmed in the TrialNet subjects (Supp. Figure 10). Notably we found that pre-diagnosis IgG1 and IgG2 titers against the R.faecis, S.gallolyticus and Bact. fragilis strains were associated with islet autoantibody specificity in an HLA-dependent manner (Figure 6 and Figure 7, orange arrow). Thus, in addition to an HLA-DR-dependent association with a future diagnosis of T1D, ACAb responses are also associated with islet autoantibody specificity. These findings reveal a central role of high risk HLA haplotypes in the relationship between islet autoimmunity, diabetes development and systemic antibodies to commensal bacteria.

HLA haplotypes are strongly associated with multiple human autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases (5). Several studies in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have provided evidence that disease-related HLA haplotypes may also be associated with immune responses to microbes. In RA patients, peptides derived from the gut commensal Prevotella copri and presented by HLA-DR stimulated inflammatory responses. Serum IgA and IgG antibodies to P. copri were also associated with titres of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (43), a biomarker of RA onset (44).

Here we report correlation between specific islet autoantibodies and IgG1 and IgG2, likely T cell-dependent, ACAb responses (Figure 5). An important limitation of our study is that the bacterial strains used to reveal ACAb are proxies for those that triggered the initial B cell responses in these subjects. These findings raise the possibility that some antibodies against commensals may cross-react with self-antigens. A characterization of the reactivity profile of intestinal plasmablasts isolated from healthy subjects revealed that 25% of intestinal IgA and IgG antibodies were polyreactive with diverse foreign and self-antigens, including insulin and bacterial lipopolysaccharide (45). In patients with RA or autoimmune hepatitis, antibodies against mucosal pathogens were correlated with disease associated auto-antibodies (46, 47). A recent study in the NOD mouse demonstrated molecular mimicry between an integrase peptide derived from the common gut commensal Bacteroides and an islet antigen. In this model, colonization with a Bacteroides encoding the integrase was required to recruit these islet-antigen specific CD8 T cells to the gut where they protected from chemically induced colitis (48). Thus, in some settings, immune responses against microbial antigens may contribute to tissue homeostasis. In addition, polyreactive antibody responses established by recognition of commensal bacterial antigens may be adaptive for the host response against pathogens expressing cross-reactive antigens (49).

We have developed a framework to investigate human adaptive immune responses against gut commensal bacteria. The bacterial targets we examined were isolated from healthy human donors and selected to represent keystone species of the gut microbiome or based on previous evidence for association with beta cell autoimmunity (9). Could the systemic ACAb response patterns we report be associated with the composition of a subject’s intestinal microbiome? Address of this question requires longitudinal studies that enable coordinated analyses of host genetic and clinical covariates, fecal metagenomics and ACAb responses. Given extensive bacterial strain variation in gene content (15), characterization of isolates from the human subjects of interest will provide optimal targets for immune response analyses, and to identify a spectrum of relevant microbial antigens.

Our study identifies a robust relationship between immune responses to intestinal bacteria, a future T1D diagnosis, antibody responses to islet autoantigens and high-risk HLA haplotypes. Additional studies in independent cohorts of subjects are required to determine whether patterns of ACAb responses reported here may be predictive of progression to islet autoimmunity and diabetes. Our approach provides an “immune system’s view” of the microbiome, and complements efforts to identify associations between the genomic composition of fecal microbes and autoimmune diseases. The key effects of the microbiota may well be mediated by their indirect regulation of host functions, particularly immune responses beyond the gut mucosal environment.

Materials and Methods

Human Serum Samples:

Samples from two independent studies were examined for ACAb responses. The “NET” samples were obtained from Canadian pediatric (<18 years old) subjects who were either healthy controls (n=90), patients with Crohn’s disease (n=32) or patients with type 1 diabetes (n=49). Samples from subjects with either T1D or CD were collected within 6 months of clinical diagnosis from patients who had not been exposed to corticosteroids or other immune modulatory treatments. Control samples were collected from pediatric subjects, without any disease within the study follow-up period.

A second set of samples was obtained from the Pathway to Prevention TrialNet program. These subjects are relatives of diabetic individuals and are screened longitudinally for appearance of islet autoantibodies and T1D. Individuals identified as having increased risk based on islet autoantibody appearance are followed and offered clinical trial options (18). TrialNET serum samples were obtained from age-, sex- and HLA-matched subjects who displayed 0 or 1 islet autoantibody (“controls” n=62) or who became seropositive for ≥ 2 islet autoantibodies and developed T1D within the study period (ranging from 0.78 – 7.89 years from enrollment; “cases” n=68). The distribution of ages at serum collection varied from 3.1 – 48.1 years. Samples collected from individuals ≤18 years of age were included in the present study.

Serum preparation:

Frozen serum samples were thawed on ice and heated (56 °C for 30 min) to inactivate complement. Samples were then centrifuged (13,000 RPM for 10 min). Serial dilutions of these supernatants (50 μl of 1/50, 1/150, 1/450 and 1/1350 dilutions) were distributed into 96-well plates diluted in Wash Buffer consisting of sterile-filtered phosphate buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (Wisent), 5 mM EDTA (Invitrogen) and 5 mM D-Galactose (Sigma-Aldrich Canada).

Human Commensal Bacterial Collections:

The bacterial strains used in this study were isolated and archived by Emma Allen-Vercoe either as part of the Human Microbiome Project Reference Genome Collection, or as part of a study to characterize the microbiota of a healthy human donor for metabolomic assessment (16). Lactobacillus acidophilus was isolated from a probiotic preparation, VSL#3 (Alfasigma Inc.) The strains are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Bacterial Preparation:

Bacteria were resuscitated from axenic, frozen stocks on Fastidious Anaerobe Agar (Neogen Corporation) supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep’s blood (Hemostat Laboratories), under anaerobic conditions (85% N2, 10% H2 and 5% CO2) at 37°C for 48–72 h. Representative biomass was scraped from freshly-grown plates and re-suspended in 1mL sterile PBS, washed twice with 10 mL of PBS (13,000 RPM, 4 °C, 10 min) and re-suspended at 107 bacteria/mL. For assessment of antibody responses to the 32 strain MET-2 consortium, the concentration of each cultured strain was then adjusted to 107 bacteria/mL and admixed in equal proportions.

Anti-Commensal Antibody Assay:

50 μl of serially diluted samples were incubated with 50 μl of bacteria (~5 × 105 bacteria) at 4 °C for 1–2 h, and then washed twice with wash buffer (13,000 RPM, 4 °C, 10 min). Bacteria were then incubated (30 min at 4 °C) with 50 μL of fluorophore-conjugated anti-isotype antibodies (goat anti-human IgG (DyLight 405 conjugated, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.), mouse anti-human IgG1 (phycoertherin conjugated, SouthernBiotech), mouse anti-human IgG2 (AF647 conjugated, SouthernBiotech) or mouse anti-human IgA (FITC conjugated, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) (Figure 1). Bacteria were washed twice with PBS and re-suspended in 200 μL of 2% paraformaldeyhde (Canemco Inc.). The samples were analysed using an LSR Fortessa (Becton Dickinson) with settings pre-optimized for bacterial cell detection. Flow cytometry analysis of serum samples was performed using FlowJo software (Treestar, Inc.).

Calculation of Response Indices:

Human serum concentrations (4/serum sample) and their corresponding mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values were log2 transformed and linearly regressed using Prism (GraphPad Prism, GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA) to produce 1 regression line for each sample/isotype/bacteria target combination. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for each regression line. These AUCs were directly proportional to serum ACAb responses and were compared to the average AUC of all samples for each bacterial target and antibody isotype combination. The differences between sample AUC and the average AUC were expressed as ΔAUC. Response indices are the 2ΔAUC values, such that the average of all AUCs becomes 1 and sample responses are positive values and either greater than or less than 1 (Figure 1).

Islet autoantibodies:

In TrialNet case subjects the ICA status was the seropositivity status of the serum sample used in the ACAb assay. For antibodies against biochemically-defined antigens (IAA, IA2A and GADA) the autoantibody status was considered positive if the subject had seroconverted and negative if the subject had never seroconverted or had reverted at the time of ACAb serum sample collection. Seroconversion was defined as two repeat measures of the same autoantibody. Reversion was defined as two or more autoantibody negative measures following seroconversion (50).

Statistical Analysis:

All statistical analyses were performed in R (https://www.R-project.org/). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed on anti-commensal antibody responses using the prcomp function in the base package. To account for variable collinearity which can produce unstable Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) discriminators, collinear variables were removed using stepwise Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) selection (VIF threshold = 10). LDA on VIF-selected ACAb response indices was performed using the MASS, cars, and base packages. To assess the discrimination power of the LDA function, repeated (100x) 2-fold cross-validation was performed using the MASS and base packages. To account for unbalanced case vs. healthy control numbers, cross-validation was performed using samples bootstrap-rarefied to the condition with fewest samples. Linear regression of ACAb responses against various explanatory variables (clinical status, HLA haplotypes, islet autoantibody specificity, age) was performed using the base and phia R packages. The significance of the interaction term in the linear model was assessed using the anova function comparing the additive model to the model with an interaction term. Age adjustment was performed by adding age as a covariate in the linear regression model. Multiple testing correction was performed by controlling the false discovery rate (FDR) for the family of tests performed using the p.adjust function in R.

The association of islet autoantibodies and ACAb responses was investigated using a stepwise hypothesis testing approach. 1) The main effect of every autoantibody specificity was tested for every ACAb response. Nominally significant associations (p<0.05, q<0.5) were further investigated at the next step. 2) For nominally significant autoantibody-ACAb associations from step 1, the regression model was adjusted by addition of the HLA haplotypes DR3 or DR4 to test whether the autoantibody specificity effect was HLA-dependent. Tests performed at step 1 and step 2 were corrected for multiple testing by controlling the FDR. Autoantibody-ACAb response associations with q<0.2 either at step 1 or step 2 were considered significant and are reported in Figure 6.

The regularized Canonical Correlation Analysis (rCCA) was performed using the mixOmics R package on the ACAb responses and autoantibody positivity data to extract relationships between these two multidimensional datasets. Specifically, CCA maximizes the correlation between linear combinations of variables from the two datasets (i.e. ACAb responses and autoantibody positivity), while adjusting for the within-dataset correlations and is therefore a more powerful approach compared to performing pairwise correlations between the variables.

The cor.test function was used to test correlation between pairs of anti-commensal antibody responses. Plots were generated using the ggplot2 and ggrepel packages.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors acknowledge serum samples from the CIHR/MSSC NET study in Clinical Autoimmunity Co-Principal Investigators: Amit Bar-Or, Brenda Banwell, Anne Griffiths, Mark Silverberg, Ciriaco Piccirillo, Constantin Polychronakos, and Philip Sherman, and from the TrialNet Biorepository through an ancillary study to the Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Pathway to Prevention Study (TN-01).

Funding: J.S.D. acknowledges support of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF)., the Hospital for Sick Children Research Foundation and the Anne and Max Tanenbaum Chair, University of Toronto. E.A-V. acknowledges funding from the National Science and Engineering Council of Canada. A.P. was supported by fellowships from the JDRF and CIHR.

TrialNet TN-01 is supported by NIH grants U01 DK061010, U01 DK061034, U01 DK061042, U01 DK061058, U01 DK085465, U01 DK085461, U01 DK085466, U01 DK085476, U01 DK085499, U01 DK085509, U01 DK103180, U01 DK103153, U01 DK103266, U01 DK103282, U01 DK106984, U01 DK106994, U01 DK107013, U01 DK107014, UC4 DK106993, and the JDRF.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interests with this study.

Data and Materials Availability: Raw data including flow cytometry files are available by request.

References

- 1.Bach JF, The hygiene hypothesis in autoimmunity: the role of pathogens and commensals. Nat Rev Immunol 18, 105–120 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gill T, Asquith M, Rosenbaum JT, Colbert RA, The intestinal microbiome in spondyloarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 27, 319–325 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scher JU, Abramson SB, The microbiome and rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 7, 569–578 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kostic AD, Gevers D, Siljander H, Vatanen T, Hyotylainen T, Hamalainen AM, Peet A, Tillmann V, Poho P, Mattila I, Lahdesmaki H, Franzosa EA, Vaarala O, de Goffau M, Harmsen H, Ilonen J, Virtanen SM, Clish CB, Oresic M, Huttenhower C, Knip M, D. S. Group, Xavier RJ, The dynamics of the human infant gut microbiome in development and in progression toward type 1 diabetes. Cell Host Microbe 17, 260–273 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karnes JH, Bastarache L, Shaffer CM, Gaudieri S, Xu Y, Glazer AM, Mosley JD, Zhao S, Raychaudhuri S, Mallal S, Ye Z, Mayer JG, Brilliant MH, Hebbring SJ, Roden DM, Phillips EJ, Denny JC, Phenome-wide scanning identifies multiple diseases and disease severity phenotypes associated with HLA variants. Sci Transl Med 9, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardner SG, Bingley PJ, Sawtell PA, Weeks S, Gale EA, Rising incidence of insulin dependent diabetes in children aged under 5 years in the Oxford region: time trend analysis. The Bart’s-Oxford Study Group. BMJ 315, 713–717 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuomilehto J, Virtala E, Karvonen M, Lounamaa R, Pitkaniemi J, Reunanen A, Tuomilehto-Wolf E, Toivanen L, Increase in incidence of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus among children in Finland. Int J Epidemiol 24, 984–992 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krischer JP, Lynch KF, Schatz DA, Ilonen J, Lernmark A, Hagopian WA, Rewers MJ, She JX, Simell OG, Toppari J, Ziegler AG, Akolkar B, Bonifacio E, T. S. Group, The 6 year incidence of diabetes-associated autoantibodies in genetically at-risk children: the TEDDY study. Diabetologia 58, 980–987 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Goffau MC LK, Knip M, Ilonen J, Ruohtula T, Härkönen T, Orivuori L, Hakala S, Welling GW, Harmsen HJ, Vaarala O, Fecal Microbiota Composition Differs Between Children With β-Cell Autoimmunity and Those Without. Diabetes 62, 1238–1244 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Goffau MC FS, van den Bogert B, Honkanen H, de Vos WM, Welling GW, Hyöty H, Harmsen HJM, Aberrant gut microbiota composition at the onset of type 1 diabetes in young children. Diabetologia 57, 1569–1577 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giongo A, Gano KA, Crabb DB, Mukherjee N, Novelo LL, Casella G, Drew JC, Ilonen J, Knip M, Hyoty H, Veijola R, Simell T, Simell O, Neu J, Wasserfall CH, Schatz D, Atkinson MA, Triplett EW, Toward defining the autoimmune microbiome for type 1 diabetes. ISME J 5, 82–91 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moor K, Fadlallah J, Toska A, Sterlin D, Balmer ML, Macpherson AJ, Gorochov G, Larsen M, Slack E, Analysis of bacterial-surface-specific antibodies in body fluids using bacterial flow cytometry. Nat Protoc 11, 1531–1553 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slack E HS, Stecher B, Velykoredko Y, Stoel M, Lawson MA, Geuking MB, Beutler B, Tedder TF, Hardt WD, Bercik P, Verdu EF, McCoy KD, Macpherson AJ, Innate and Adaptive Immunity Cooperate Flexibly to Maintain Host-Microbiota Mutualism. Science 325, 617–620 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haas A, Zimmermann K, Graw F, Slack E, Rusert P, Ledergerber B, Bossart W, Weber R, Thurnheer MC, Battegay M, Hirschel B, Vernazza P, Patuto N, Macpherson AJ, Gunthard HF, Oxenius A, H. I. V. C. S. Swiss, Systemic antibody responses to gut commensal bacteria during chronic HIV-1 infection. Gut 60, 1506–1519 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenblum S, Carr R, Borenstein E, Extensive strain-level copy-number variation across human gut microbiome species. Cell 160, 583–594 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yen S, McDonald JA, Schroeter K, Oliphant K, Sokolenko S, Blondeel EJ, Allen-Vercoe E, Aucoin MG, Metabolomic analysis of human fecal microbiota: a comparison of feces-derived communities and defined mixed communities. J Proteome Res 14, 1472–1482 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belabani C, Rajasekharan S, Poupon V, Johnson T, Bar-Or A, C. M. N. i. C. Autoimmunity, N. Canadian Pediatric Demyelinating Disease, A condensed performance-validation strategy for multiplex detection kits used in studies of human clinical samples. J Immunol Methods 387, 1–10 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Battaglia M, Anderson MS, Buckner JH, Geyer SM, Gottlieb PA, Kay TWH, Lernmark A, Muller S, Pugliese A, Roep BO, Greenbaum CJ, Peakman M, Understanding and preventing type 1 diabetes through the unique working model of TrialNet. Diabetologia 60, 2139–2147 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erlich H, Valdes AM, Noble J, Carlson JA, Varney M, Concannon P, Mychaleckyj JC, Todd JA, Bonella P, Fear AL, Lavant E, Louey A, Moonsamy P, Type C 1 Diabetes Genetics, HLA DR-DQ haplotypes and genotypes and type 1 diabetes risk: analysis of the type 1 diabetes genetics consortium families. Diabetes 57, 1084–1092 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomson G, Valdes AM, Noble JA, Kockum I, Grote MN, Najman J, Erlich HA, Cucca F, Pugliese A, Steenkiste A, Dorman JS, Caillat-Zucman S, Hermann R, Ilonen J, Lambert AP, Bingley PJ, Gillespie KM, Lernmark A, Sanjeevi CB, Ronningen KS, Undlien DE, Thorsby E, Petrone A, Buzzetti R, Koeleman BP, Roep BO, Saruhan-Direskeneli G, Uyar FA, Gunoz H, Gorodezky C, Alaez C, Boehm BO, Mlynarski W, Ikegami H, Berrino M, Fasano ME, Dametto E, Israel S, Brautbar C, Santiago-Cortes A, Frazer de Llado T, She JX, Bugawan TL, Rotter JI, Raffel L, Zeidler A, Leyva-Cobian F, Hawkins BR, Chan SH, Castano L, Pociot F, Nerup J, Relative predispositional effects of HLA class II DRB1-DQB1 haplotypes and genotypes on type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Tissue Antigens 70, 110–127 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vatanen T, Kostic AD, d’Hennezel E, Siljander H, Franzosa EA, Yassour M, Kolde R, Vlamakis H, Arthur TD, Hamalainen AM, Peet A, Tillmann V, Uibo R, Mokurov S, Dorshakova N, Ilonen J, Virtanen SM, Szabo SJ, Porter JA, Lahdesmaki H, Huttenhower C, Gevers D, Cullen TW, Knip M, D. S. Group, Xavier RJ, Variation in Microbiome LPS Immunogenicity Contributes to Autoimmunity in Humans. Cell 165, 842–853 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vatanen T, Franzosa EA, Schwager R, Tripathi S, Arthur TD, Vehik K, Lernmark A, Hagopian WA, Rewers MJ, She JX, Toppari J, Ziegler AG, Akolkar B, Krischer JP, Stewart CJ, Ajami NJ, Petrosino JF, Gevers D, Lahdesmaki H, Vlamakis H, Huttenhower C, Xavier RJ, The human gut microbiome in early-onset type 1 diabetes from the TEDDY study. Nature 562, 589–594 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart CJ, Ajami NJ, O’Brien JL, Hutchinson DS, Smith DP, Wong MC, Ross MC, Lloyd RE, Doddapaneni H, Metcalf GA, Muzny D, Gibbs RA, Vatanen T, Huttenhower C, Xavier RJ, Rewers M, Hagopian W, Toppari J, Ziegler AG, She JX, Akolkar B, Lernmark A, Hyoty H, Vehik K, Krischer JP, Petrosino JF, Temporal development of the gut microbiome in early childhood from the TEDDY study. Nature 562, 583–588 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonifacio E, Ziegler AG, Advances in the prediction and natural history of type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 39, 513–525 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steck AK, Vehik K, Bonifacio E, Lernmark A, Ziegler AG, Hagopian WA, She J, Simell O, Akolkar B, Krischer J, Schatz D, Rewers MJ, T. S. Group, Predictors of Progression From the Appearance of Islet Autoantibodies to Early Childhood Diabetes: The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY). Diabetes Care 38, 808–813 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graham J HW, Kockum I, Li LS, Sanjeevi CB, Lowe RM, Schaefer JB, Zarghami M, Day HL, Landin-Olsson M, Palmer JP, Janer-Villanueva M, Hood L, Sundkvist G, Lernmark A, Breslow N, Dahlquist G, Blohmé G, Genetic effects on age-dependent onset and islet cell autoantibody markers in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 51, 1346–1355 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hagopian WA, Sanjeevi CB, Kockum I, Landin-Olsson M, Karlsen AE, Sundkvist G, Dahlquist G, Palmer J, Lernmark A, Glutamate decarboxylase-, insulin-, and islet cell-antibodies and HLA typing to detect diabetes in a general population-based study of Swedish children. J Clin Invest 95, 1505–1511 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bach J, The effect of infections on susceptibility to autoimmune and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med 347, 911–920 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kemppainen KM AA, Davis-Richardson AG, Fagen JR, Gano KA, León-Novelo LG,Vehik K, Casella G, Simell O, Ziegler AG, Rewers MJ,Lernmark A, Hagopian W, She J-X,Krischer JP,Akolkar B, Schatz DA,Atkinson MA, Triplett EW and the TEDDY Study Group, Early Childhood Gut Microbiomes Show Strong Geographic Differences Among Subjects at High Risk for Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 38, 329–332 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alkanani AK HN, Gottlieb PA, Ir D, Robertson CE, Wagner BD, Frank DN, Zipris D, Alkanani AK, Hara N, Gottlieb PA, et al. Alterations in Intestinal Microbiota Correlate With Susceptibility to Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64(10):3510–3520. doi: 10.2337/db14-1847 Diabetes 64, 3510–3520 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown CT, Davis-Richardson AG, Giongo A, Gano KA, Crabb DB, Mukherjee N, Casella G, Drew JC, Ilonen J, Knip M, Hyoty H, Veijola R, Simell T, Simell O, Neu J, Wasserfall CH, Schatz D, Atkinson MA, Triplett EW, Gut microbiome metagenomics analysis suggests a functional model for the development of autoimmunity for type 1 diabetes. PLoS One 6, e25792 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mejia-Leon ME, Petrosino JF, Ajami NJ, Dominguez-Bello MG, de la Barca AM, Fecal microbiota imbalance in Mexican children with type 1 diabetes. Sci Rep 4, 3814 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Endesfelder D, Engel M, Davis-Richardson AG, Ardissone AN, Achenbach P, Hummel S, Winkler C, Atkinson M, Schatz D, Triplett E, Ziegler AG, zu Castell W, Towards a functional hypothesis relating anti-islet cell autoimmunity to the dietary impact on microbial communities and butyrate production. Microbiome 4, 17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimmermann K, Haas A, Oxenius A, Systemic antibody responses to gut microbes in health and disease. Gut Microbes 3, 42–47 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choung RS, Princen F, Stockfisch TP, Torres J, Maue AC, Porter CK, Leon F, De Vroey B, Singh S, Riddle MS, Murray JA, Colombel JF, P. S. Team, Serologic microbial associated markers can predict Crohn’s disease behaviour years before disease diagnosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 43, 1300–1310 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hevia A, Lopez P, Suarez A, Jacquot C, Urdaci MC, Margolles A, Sanchez B, Association of levels of antibodies from patients with inflammatory bowel disease with extracellular proteins of food and probiotic bacteria. Biomed Res Int 2014, 351204 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Antoni L, Nuding S, Wehkamp J, Stange EF, Intestinal barrier in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 20, 1165–1179 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coskun M, Intestinal epithelium in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Med (Lausanne) 1, 24 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bosi E, Molteni L, Radaelli MG, Folini L, Fermo I, Bazzigaluppi E, Piemonti L, Pastore MR, Paroni R, Increased intestinal permeability precedes clinical onset of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 49, 2824–2827 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuitunen M, Saukkonen T, Ilonen J, Åkerblom HK, Savilahti E, Intestinal Permeability to Mannitol and Lactulose in Children with Type 1 Diabetes with the HLA-DQB1*02 Allele. Autoimmunity 35, 365–368 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Secondulfo M, Iafusco D, Carratù R, deMagistris L, Sapone A, Generoso M, Mezzogiorno A, Sasso FC, Cartenì M, De Rosa R, Prisco F, Esposito V, Ultrastructural mucosal alterations and increased intestinal permeability in non-celiac, type I diabetic patients. Digestive and Liver Disease 36, 35–45 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christmann BS, Abrahamsson TR, Bernstein CN, Duck LW, Mannon PJ, Berg G, Bjorksten B, Jenmalm MC, Elson CO, Human seroreactivity to gut microbiota antigens. J Allergy Clin Immunol 136, 1378–1386 e1371–1375 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pianta A, Arvikar S, Strle K, Drouin EE, Wang Q, Costello CE, Steere AC, Evidence of the Immune Relevance of Prevotella copri, a Gut Microbe, in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 69, 964–975 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, de Jong BA, Berglin E, Hallmans G, Wadell G, Stenlund H, Sundin U, van Venrooij WJ, Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 48, 2741–2749 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benckert J, Schmolka N, Kreschel C, Zoller MJ, Sturm A, Wiedenmann B, Wardemann H, The majority of intestinal IgA+ and IgG+ plasmablasts in the human gut are antigen-specific. J Clin Invest 121, 1946–1955 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lundberg K, Kinloch A, Fisher BA, Wegner N, Wait R, Charles P, Mikuls TR, Venables PJ, Antibodies to citrullinated alpha-enolase peptide 1 are specific for rheumatoid arthritis and cross-react with bacterial enolase. Arthritis Rheum 58, 3009–3019 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manfredo Vieira S, Hiltensperger M, Kumar V, Zegarra-Ruiz D, Dehner C, Khan N, Costa FRC, Tiniakou E, Greiling T, Ruff W, Barbieri A, Kriegel C, Mehta SS, Knight JR, Jain D, Goodman AL, Kriegel MA, Translocation of a gut pathobiont drives autoimmunity in mice and humans. Science 359, 1156–1161 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hebbandi Nanjundappa R, Ronchi F, Wang J, Clemente-Casares X, Yamanouchi J, Sokke Umeshappa C, Yang Y, Blanco J, Bassolas-Molina H, Salas A, Khan H, Slattery RM, Wyss M, Mooser C, Macpherson AJ, Sycuro LK, Serra P, McKay DM, McCoy KD, Santamaria P, A Gut Microbial Mimic that Hijacks Diabetogenic Autoreactivity to Suppress Colitis. Cell 171, 655–667 e617 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeng MY, Cisalpino D, Varadarajan S, Hellman J, Warren HS, Cascalho M, Inohara N, Nunez G, Gut Microbiota-Induced Immunoglobulin G Controls Systemic Infection by Symbiotic Bacteria and Pathogens. Immunity 44, 647–658 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vehik K, Lynch KF, Schatz DA, Akolkar B, Hagopian W, Rewers M, She JX, Simell O, Toppari J, Ziegler AG, Lernmark A, Bonifacio E, Krischer JP, T. S. Group, Reversion of beta-Cell Autoimmunity Changes Risk of Type 1 Diabetes: TEDDY Study. Diabetes Care 39, 1535–1542 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.