Summary

Genomic amplification of 3q26.2 locus leads to the increased expression of microRNA 551b-3p (miR551b-3p) in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Our results demonstrate that miR551b-3p translocates to the nucleus with the aid of importin-8 (IPO8) and activates STAT3 transcription. As a consequence, miR551b upregulates the expression of Oncostatin M receptor (OSMR) and interleukin-31 receptor-α (IL31RA) as well as their ligands Oncostatin-M (OSM) and interleukin 31 (IL31) through STAT3 transcription. We defined this set of genes induced by miR551b-3p as “Oncostatin signaling module”, which provides oncogenic addictions in cancer cells. Notably, OSM is highly expressed in TNBC and the elevated expression of OSM associates with poor outcome in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer patients. Conversely, targeting miR551b with anti-miR551b-3p reduced the expression of OSM signaling module, and reduced tumor growth as well as migration and invasion of breast cancer cells.

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs), a class of small (~22 nucleotides long) non-coding RNAs, have been implicated in multiple important physiological and pathological processes (Calin, 2009). miR551b is part of the 3q26.2 chromosomal locus, which is frequently amplified in breast cancer (Weber-Mangal et al., 2003) as well as in multiple other cancer lineages, including cervical, head and neck, and prostate cancers (Nanjundan et al., 2007). We found that miR551b directly activates transcription via RNA activation (RNAa) to increase transcription of the signal transducer and activator of transcription factor 3 (STAT3) oncogene (Chaluvally-Raghavan et al., 2016b). In concordance with our studies, others also have reported that small RNAs like microRNAs could interact with the promoter sequence and activate transcription of genes (Huang et al., 2012; Matsui et al., 2013; Place et al., 2008).

STAT3 is a well-known oncogenic transcription factor that is upregulated in many cancers, including breast and ovarian cancers (Chaluvally-Raghavan et al., 2016b), but it is unclear how RNAa upregulates the expression of oncogenes such as STAT3 in tumor cells. It is known that cytokines or growth factors promotes the phosphorylation of STAT3 within the cytoplasm, leading to STAT3 dimerization, nuclear translocation, and binding to oncogene promoters. STAT3 is known for its role on the transcription of growth factors, cytokines, and their receptors and causes autocrine signaling (Rosen et al., 2006). We have shown that miR551b-3p interacts with promoter sequences of STAT3 to facilitate the recruitment of RNA-polymerase-II and TWIST1 transcription factor, increasing STAT3 transcription (Chaluvally-Raghavan et al., 2016b). While our previous study identified miR551b as a key mediator of STAT3 transcription through RNAa (Chaluvally-Raghavan et al., 2016b), it did not elucidate the functional consequences of the miR551b-STAT3 signaling cascade.

In the current study, we demonstrate that miR551b–STAT3 signaling axis upregulates a set of genes for the OSM family of chemokines, including OSM and IL31, and their receptors OSM receptor (OSMR) and interleukin-31 receptor-α (IL31RA). We named this set of genes as “Oncostatin gene module”. Studies have shown that the defined set of genes in specific modules could act as a self-sustained signaling-loop, which can feed signaling cues consistently for prolonged periods and regulates the gene expression for decisive cellular outputs (Amit et al., 2007a). OSMR, a member of the type I cytokine receptor family (Bilsborough et al., 2010), is the primary receptor for OSM. OSMR hetero-dimerizes with interleukin-6 signal transducer (IL6ST, also known as gp130) upon binding with OSM (Godoy-Tundidor et al., 2005). OSMR also hetero-dimerizes with IL-31RA upon binding with interleukin-31 (IL31) (Yu et al., 2014). Studies have reported that elevated levels of OSM expression results in a feed-forward loop involving the de novo production of both OSM and OSMR to facilitate aggressive properties of cancer cells (Kucia-Tran et al., 2018). However, the role of miR551b-mediated upregulation of Oncostatin gene module in basal-like breast cancers have not been well understood. In this study, we uncover the mechanism how mature microRNA-551b-3p translocated to the nucleus and upregulates OSM gene module for breast cancer progression.

RESULTS

miR551b Increases Cell Proliferation, Migration and Invasion in Breast Cancer Cells

To explore the oncogenic role of miR551b-3p in breast cancer, firstly we determined the expression of miR551b3p in different breast cancer cell lines represent different subtypes of breast cancer and found that basal-like triple negative breast cancer cells (TNBC) such as MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-436, SUM-149 and HCC-1806RR express high levels of miR551b-3p compared to ER-positive luminal cell lines like T47D, and MCF-7 and HER2 expressing cell line BT-474 cells (Figure-S1A). To determine the role of miR551b-3p in basal-like breast cancer cells, we used MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cell lines. MCF10A cell line is a spontaneously immortalized breast epithelial cell line derived from the benign breast tissue of a woman. Both MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cell lines do not express ER, PR and HER2 and express wild-type BRCA1, thus exhibit the characteristics of basal-like TNBC samples in the clinic (Chavez et al., 2010; Paine et al., 1992; Soule et al., 1990). Our results show that miR551b-3p increased the proliferation (Figures–1A) and clonogenic potential of both MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells (Figures–1B and S1B) as well as promoted the migration and invasion of both MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells (Figures–1C). Furthermore, miR551b increased the wound healing ability of MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells (Figures–1D) and increased the levels of Vimentin and N-cadherin and reduced the levels of E-cadherin (Figures–1E and 1F; and see Figures-S1C for miRNA expression).

Figure-1. b-3p promotes oncogenic features in breast cancer cells.

A-B, Cell lines were transfected with control miR or miR551b-3p and the viability was assessed at the indicated time points, using MTT. Cell lines above were also assessed for their colony-forming ability 14 days after transfection by staining with crystal violet *P < 0.05, vs. control (con) miR. C, Representative images (scale bars represent 500 μm) of transfected (with con. miR or miR551b-3p) MCF10A or MDA-MB-231 cells that migrated or invaded through trans-well inserts with or without Matrigel and the quantification of absorbance crystal violet eluted. D, Representative images of three microscopic fields in a wound-healing assay of MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells captured at 24h after transfection with con. miR and different concentrations of miR551b-3p. Red-line indicates the empty space between healing cells. Scale bars represent 500 μm. E. Cell lines were transfected with control miR (7nM) and miR551b-3p at the indicated concentrations and immunoblotted 48 h after transfection. F, Total RNA was isolated from samples (as indicated in E) and qPCR was performed. mRNA expression was normalized to ß-actin. Bars represent S.E. of triplicate determinations. G, Cells were transfected with control miR (7nM) or miR551b-3p at the indicated concentrations and representative images of MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 spheroids formed on a low- attachment plate were captured. Scale bars represent 500 μm. H, Total RNA was isolated from samples (as indicated in F), and qPCR was performed. Error bars represent standard errors (SE) of triplicates. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis.

Next we used a model that reflect in vivo conditions better we transfected miR551b into MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells and cultured the cells on non-adherent condition and in matrigel to form spheroids. Importantly, miR551b-3p increased the number and size of spheroids and the invasion of MDA-MB-231 tumor spheroids (Figures–1G and S1D). We and others have previously showed that cells in tumor spheroids exhibit characteristics of cancer stem cells (CSC) and express EMT markers (Chaluvally-Raghavan et al., 2016b; Chaluvally-Raghavan et al., 2014; Mani et al., 2008; Pradeep et al., 2012a). Complementing these findings, we found that miR551b-3p upregulates expression of CD44, and c-Kit, and downregulates expression of CD24 and E-cadherin (Figures–1H). To determine if miR551b induce the TNBC characteristics like mesenchymal properties and cancer stemness in luminal breast cancer cells, we overexpressed miR551b-3p in a luminal cell line MCF-7 and found that the gain of miR551b-3p in MCF-7 cells, increased the levels of Vimentin, N-Cadherin and reduced the levels of E-Cadherin (Figure-S1E). We also found that miR551b-3p upregulated the expression of CD44 and downregulated CD24, which demonstrates the acquisition of the characteristics of cancer stemness in MCF-7 cells (Figure-S1F). We also found that miR-551b-3p promoted the migration, invasion, and sphere forming and colony forming ability of MCF-7 cells (Figures-S1G and S1H).

Inhibition of miR551b Decreases the Tumorigenic Features of Breast Cancer Cells

Consistent with the finding that miR551b-3p confers oncogenic properties, knockdown of miR551b-3p reduced proliferation and colony forming activity of MDA-MB-231 cells (Figures–2A to 2C and see S2A for miR551b-3p expression). Furthermore, anti-miR551b-3p promotes apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure-2D). In parallel to anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of anti-miR551b-3p, we found that anti-miR551b-3p reduced migration and invasion of MDA-MB-231 and HCC-1806RR cells (Figures–2E, 2F and S2B). Anti-miR551b-3p also reduced the number and size of MDA-MB-231 spheroids in both non-adherent and adherent conditions and HCC-1806RR spheroids in non-adherent conditions (Figures–2G, S2C and S2D). We also noticed that anti-miR551b reduced the expression of vimentin and N-cadherin, and increased the expression of E-cadherin in both MDA-MB-231 and HCC-1806RR cell lines, which expresses high levels of miR551b-3p (Figures–2H, 2I and S2E),and decreased stem cell characteristics as displayed by decreased levels of CD44 and c-Kit, and increased levels of CD24 in both MDA-MB-231 and HCC-1806RR cell lines (Figures–2J and S2F).

Figure-2. Inhibition of miRNA 551b-3p reduces oncogenic properties of breast cancer cells.

A-B, MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with con. anti-miR or anti-miR551b-3p at different concentrations, and cell viability was assessed at the indicated time point using MTT and their colony-forming ability was assessed after 14 days. Error bars represent SE of quadruplicates, and P values were determined by Student’s t-test. *indicates P < 0.05 compared to the control group. C, Quantitative analysis of the colony-forming assay in (B). D, MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with con. anti-miR (7nM) or anti-miR551b (7nM) for 48h, and the numbers of apoptotic cells (Q1) and viable cells (Q3) were assessed with a calcein AM/ethidium bromide (EtBr) assay kit, using flow cytometry. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments in triplicate. E–F, MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with con. anti-miR or anti-miR551b-3p and plated onto trans-well inserts. Migrated or invaded cells were photographed (upper panel). Scale bars represent 500 μm. Bar graph represents the quantification of the cells migrated or invaded. G, The cells were transfected with control anti-miR or anti-miR551b-3p at the indicated concentrations and the spheroids formed on low attachment plates were photographed and quantitated on day 7. Scale bars represent 500 μm. H, Total RNA extracted from cells were transfected with control anti-miR or anti-miR551b-3p (7nM) 48h after transfection, and qPCR was performed to determine indicated genes. I, Cell lysates were prepared 48 h after transfection of con. anti-miR or anti-miR551b-3p (7nM) and immunoblotting was performed. J, qPCR was performed using total RNA was extracted from (I) to determine the expression of indicated genes. All mRNAs were normalized to ß-actin in qPCR assays. Bars represent S.E. of triplicate determinations. Statistical analysis was done by Student’s t-test.

miR551b-3p Upregulates STAT3 Transcription Factor and OSM Gene Module

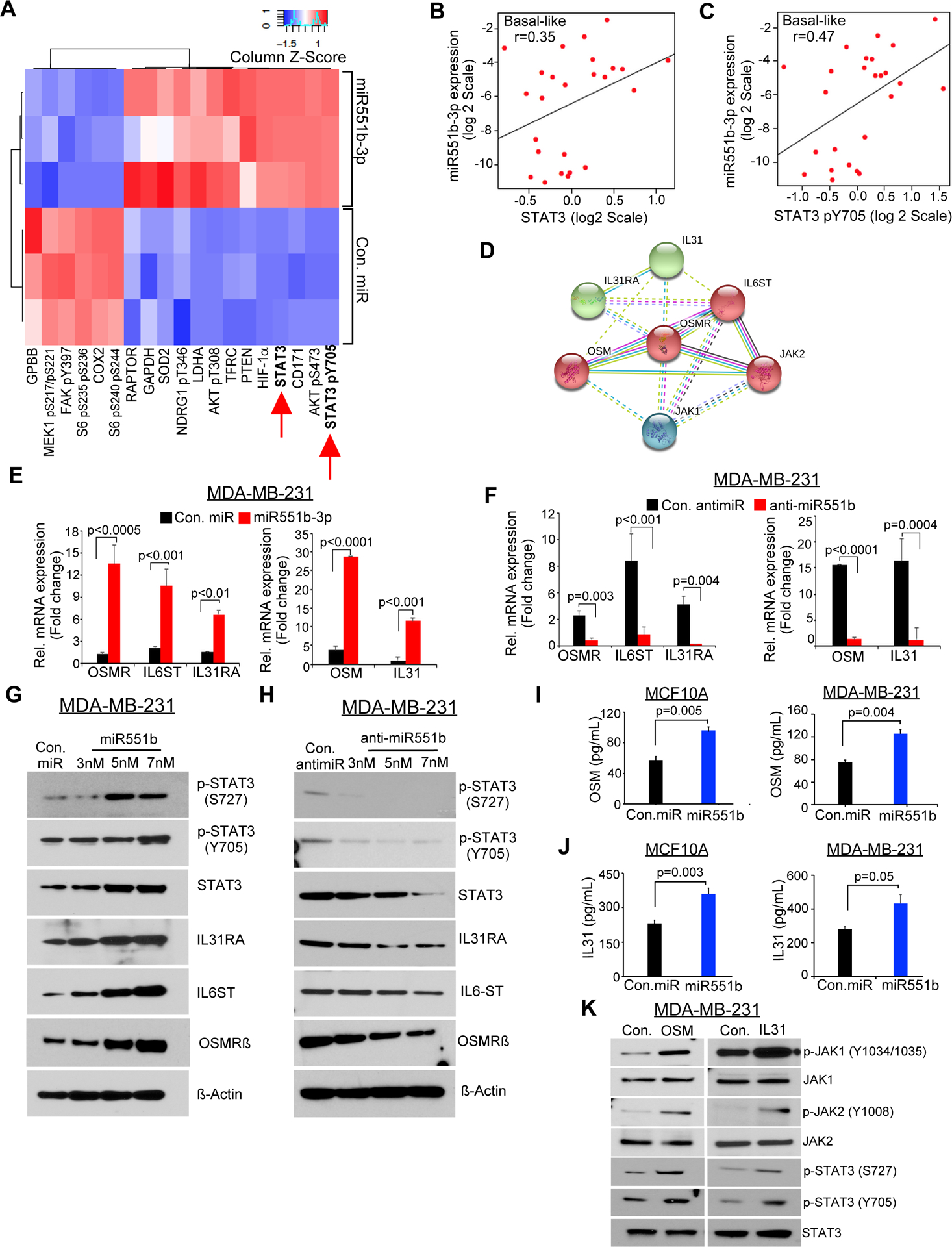

To explore the mechanisms by which miR551b-3p mediates its effects in TNBC, we assessed the changes in protein expression resulting from miR551b-3p expression in MDA-MB-231 cells, using reverse phase protein array (RPPA) as described before (Hennessy et al., 2010). We found that miR551b-3p upregulated both total and phospho-STAT3 (Y705) proteins, supporting that STAT3 is the key target of miR551b-3p in breast cancer cells (Figure-3A). Furthermore, miR551b-3p increased PI3K and AKT signaling while downregulating RAS/MAPK signaling and decreasing levels of phosphorylated S6 protein (Figures–3A and S3A). These findings support the contention that increased PI3K and AKT signaling together with decreased levels of RAS/MAPK signaling by miR551b-3p constitute an important oncogenic mechanism in tumor cells.

Figure-3. b-3p regulates oncostatin gene module expression in breast cancer cells.

A, MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with con. miR or miR551b-3p in three independent experiments, and effects on protein levels were determined by RPPA 48 h later. Proteins with >20% change in expression are represented in the heatmap. B–C, Pearson correlation analysis was performed based on the expression of miR551b-3p versus STAT3 or miR551b-3p versus pSTAT3 protein levels in basal like subtype of breast cancer patient samples in the Danish Breast Cancer Cohort Group (DBCG) cohort; n = 89. D, OSMR-signaling network predicted by STRING database. E, MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with con. miR (7nM) or miR551b-3p (7nM), or F, transfected with con. antimiR (7nM) or with anti-miR551b (7nM) and qPCR was performed to test the expression of the indicated genes using RNA collected 48h after transfection. G-H, MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with indicated miRs; then immunoblot was performed 48h after transfection. I–J, Secreted levels of OSM and IL31 in the culture supernatant of MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells were collected after con. miR or miR-551b −3p transfection and quantitated by ELISA. Bars represent mean ± S.E of quadruplicate determinations of three different experiments. K, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with OSM, or IL31 (20ng/ml), then lysates were prepared and immunoblot was performed 48h after transfection.

miR551b-3p is located at the 3q26.2 locus, and the miR551b copy-gain is present in ~27% breast cancer patients and miR551b is amplified in ~3.5% breast cancer patients in the TCGA breast cancer data set (Table-S1) (Cancer Genome Atlas, 2012). Our analysis using TCGA breast cancer data further showed that breast cancer samples exhibit miR551b amplification express high levels of STAT3 mRNA (Figure-S3B) and miR551b-3p expression is correlated with STAT3 and phospho-STAT3 (Y705) levels in breast cancer samples, particularly in the basal-like subtype (Figures–3B, 3C and S3C) (Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative et al., 2006). In conjunction with our previous findings in ovarian cancer (Chaluvally-Raghavan et al., 2016b), our data demonstrate that miR551b-3p appears to regulate total and phospho-STAT3 in breast cancer cells, where miR551b-3p could be a major contributor to the functional effects of STAT3. Next, we determined if there is an association between miR551b-3p and STAT3 in the set of breast cancer cell lines, in which we have determined the expression of miR551b (see Figure-S1A) and found that those cell lines expressing high levels of miR551b-3p also express high levels of STAT3 and phosphorylated form of STAT3 (S727 and Y705) (Figure-S3D). Our correlation coefficient analysis between the expression of miR551b-3p and the levels of STAT3, pSTAT3 (Y705), or pSTAT3 (S727) again confirm a positive correlation between miR551b-3p vs STAT3 proteins (Pearson correlation coefficient [r] > 0.7) (Figure-S3D and S3E).

To identify the key transcriptional targets upregulated by STAT3 in breast cancer, we employed three breast cancer datasets including TCGA breast cancer data set (Cancer Genome Atlas, 2012), METABRIC data set and the MicMa micro-metastasis cohort of breast cancer (Enerly et al., 2011; Naume et al., 2007; Wiedswang et al., 2003) for mRNAs correlated with STAT3 mRNA. Strikingly, our analysis, using a Spearman’s correlation coefficient above 0.4, identified OSMR is the only mRNA significantly associated with STAT3 RNA in both data sets (Sheet 1 to Sheet 3 in Table-S2 and Figure-S3F). Next, we identified proteins that interact with STAT3 and OSMR, using the STRING database catalogs direct and indirect protein interactions, identified six proteins including OSM, interleukin-31 (IL31), interleukin-6 signal transducer, interleukin-31 receptor alpha (IL31RA), Janus kinase-1 (JAK1), and Janus kinase-2 (JAK2)—as primary interactors with OSMR, with an interaction score of 0.90 or above (Figures–3D and Table-S3). Taken together, our data suggests that miR551b-3p could act through a gene module consisting of OSM, OSMR, IL31, IL31RA, IL6ST, JAK1, and JAK2. Importantly miR551b-3p upregulated the expression of OSM, OSMR, IL31, IL31RA, and IL6ST, which we define as the OSM gene module and that anti-miR551b-3p reduces expression of these components at both mRNA and protein levels (Figures–3E to 3H and Figures-S3G).

OSM and IL31 are secreted cytokines and these secreted cytokines can activate cellular signaling in autocrine manner. Thus, we quantified the secreted levels of OSM and IL31 by ELISA and found that miR551b-3p increased the levels of both OSM and IL31 in supernatants of MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells (Figures–3I-3J). Conversely, anti-miR551b-3p reduced the levels of OSM and IL31 in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure-S3H). OSM or IL31 also induced the phosphorylation of JAK1 (Y-1034/1035), JAK2 (Y-1008) and STAT3 (S-727 and Y-705) in breast cancer cells (Figure–3K). We further determined the effects of OSM and IL31 on phosphorylation of STAT3 in comparison with IL6, which is a known stimulator of STAT3 phosphorylation and found that OSM induced the phosphorylation of STAT3 at Y705 and S727 residues markedly higher than IL-6 and IL-31 and persistent for prolonged period (Figures-S3I and S3J).

Mature miR551b-3p Translocate to the Nucleus for Transcriptional activation of STAT3

We have shown that miR551b-3p interacts with STAT3 promoter in the nucleus and activates STAT3 transcription previously (Chaluvally-Raghavan et al., 2016b; Ramchandran and Chaluvally-Raghavan, 2017). To determine if mature miR551b-3p is present in the nucleus and is required for transcriptional activation, we have performed qPCR to quantitate the expression of miR551b-3p in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions in breast cancer cell lines. Our qPCR and northern blot assays show that mature form of miR551b-3p translocated to the nucleus in substantial level in TNBC cell lines such as MDAMB-231 and HCC-1806RR, which express high levels of miR551b (Figures–4A and S4A). Our in situ hybridization also shows increased levels of mature miR551b-3p in the nucleus of MDAMB-231 and HCC-1806RR cells compared to MCF7 and MCF10A, which express low levels of miR551b exhibited less amount of miR551b-3p in the nucleus (Figures–4A, S4B and S4C). Importantly, the overexpression of miR551b3p in MDA-MB231 leads to the increased expression of miR551b-3p in both cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions compared to the cells transfected with control miRNA (Figure S4D). In conjunction with previous studies from us and others (Huang et al., 2010; Janowski et al., 2007; Place et al., 2008; Ramchandran and Chaluvally-Raghavan, 2017), the mutation in the STAT3 promoter sequences (Mutant #2, and #3), which is complementary to the 5’ sequences of miR551b-3p and the deletion of non-complementary loop in the STAT3 promoter (Mutant #4) abolished miR551b-3p induced promoter activity (Figures–4B and 4C). We also noticed that mutations in STAT3 promoter complementary towards 3’sequences of miR551b-3p (Mutant #1) reduced the miR551b-3p-induced promoter activity about 30%, whereas other mutations as described above reduced the promoter activity more than 75% compared to the luciferase activity induced by miR551b-3p in the cells were transfected with wild type STAT3 promoter. Collectively, our results suggest that the sequences 5’GCGACCCAUACUUGGU3’ in miR551b-3p is critical for the interaction of miR551b-3p with STAT3 promoter for STAT3 transcription.

Figure-4. b is translocated to nucleus and is mediated by Importin-8.

A, Total RNA was isolated from cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of cell lines indicated and miR551b-3p expression was analyzed by qPCR. miRNA was normalized to U6. B, The WT STAT3 promoter, including 962 bp upstream of the transcription start site (TSS), was cloned in the pLight luciferase reporter construct and co-transfected with control miRNA and miR551b-3p. Similarly, mutant STAT3 promoter constructs (#1 - #4) as indicated in (C) were co-transfected with Con. miR or miR551b-3p into MDA-MB-231 cells, then luciferase activity was assessed. C, Sequence complementarity between miR551b-3p with STAT3 promoter, and the sites and sequences of mutations prepared. D, MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with Cy3 labelled (red) miR551b or mutant miR551b, then fixed after 48h and confocal microscopy was performed, and representative images presented. Scale bars represent 20 μm. E, Nuclear translocation signal of miR551b-3p is quantitated by Image-J Coloc-2 pixel intensity spatial correlation analysis suite and Mander’s co-localization coefficient and the percentage of foci presented. F, RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay was performed following transfection with con miRNA, miR551b-3p or mutant miR551b for 48h in MDA-MB-231 cells. Lysates of transfected cells were pull down using antibodies specific to IPO8 or control IgG in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions to detect miR551b in lysates bound to IPO8. Control IgG antibody was used as negative controls for RIP, whereas U6 was used as a control for qRT-PCR and fold enrichment was calculated w.r.t. control IgG. Data presented as mean ± SE (n = 3). G, Lysates of MDA-MB-231 cells were used to perform immunoprecipitation of IPO8 as in (F) and immunoblotted for the indicated proteins. H, Total RNA was isolated from MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with siControl, siIPO8 and siIPO9 as followed by transfection with control miRNA and miR551b. miR551b expression was analyzed by qPCR 48h after transfection. miRNA expression was normalized to U6. I, Cy3 labelled miR551b (red) was transfected in the cells were pre-transfected with control siRNAs, siIPO8 or siIPO9, then fixed and imaged. Scale bars represent 20 μm. J, Nuclear translocation signal of miR551b-3p is quantitated as described in (E). K, Proposed model illustrating the transport of miR551b-3p into nucleus aided by IPO-8-AGO1 complex.

To visualize the translocation of miR551b to the nucleus, we have used the 5’ Cy3-labelled wild type miR551b-3p (5’-GCGACCCAUACUUGGUUUCAG-3’) or mutated miR551b-3p, in which UUGGUUU sequence in miR551b-3p mutated to CCAUCGG and transfected into MDA-MB-231 cells. Strikingly, we found that the mutations in UUGGUUU sequence abolished the nuclear translocation of miR551b-3p (Figures–4D, 4E and supplementary video file 1 and 2). Taken together, our results show that UUGGUUU sequence in miR551b-3p is important for its nuclear translocation and the 5’GCGACCCAUACUUGGU3’ sequence in miR551b-3p is important for STAT3 transcriptional activation. To further validate the nuclear translocation of miR551b-3p in miR551b genetic knockout model, we deleted miR-551b in a TNBC subtype Hs578T breast cancer cells using CRISPR/Cas9 vectors and the deletion of miR551b is confirmed using gel electrophoresis of the DNA fragment encompassing miR551b amplified using target specific primers and Sanger sequencing (Figures S4E to S4G). We then performed the RNA in situ hybridization of miR551b-3p and northern blot analysis using the microRNA isolated from cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. As expected, the wild type (WT) cells exhibited the expression of miR551b both in the cytoplasm and nucleus, while miR551b-deleted cells did not have any expression of miR551b in the cytoplasm and nucleus (Figure S4H and S4I). To further support our results on the nuclear translocation of mature miR551b-3p in the WT and miR551b-KO Hs578T cells, we performed RNA in situ hybridization in a cancer cell line exhibits homozygous deletion of miR551b, which did not show any presence of mature miR551b-3p in the cytoplasm or in nucleus (Figure S4J and S4K).

IPO8 is required for the nuclear translocation of miR551b-3p

It is shown recently that Importin-8 (IPO8), which is a member of the karyopherin β (a.k.a. protein import receptor importin β) family is important for the translocation of mature miRNAs to nucleus (Wei et al., 2014). To determine the role of IPO8 on the nuclear transport of miR551b-3p, we performed RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay by purifying miRNA followed by immunoprecipitation (IP) of IPO8 from the cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of the MDA-MB-231 cells which were transfected with con. miR, miR551b-3p or mutant miR551b. We found that miR-551b-3p but not the con. miR or mutated miR551b-3p is enriched in the nuclear fraction, when we purified IPO8 bound miRNAs from the nuclear extract (Figure–4F). Next, we performed IP of IPO8 in cytoplasmic and nuclear extract to determine if IPO8 would interact with the proteins which are required for transcription and found that IPO8 interacts with RNA-Polymerase-II and TWIST1 transcription factor in nuclear extract (Figure–4G). Next, we determined the IPO8 levels in a set of breast cancer cell lines and found that TNBC cells express high levels of IPO8 (Figures- S5A and S5B), which also express high levels of STAT3 and miR551b-3p (Figures- S1A and S3D).

To further confirm the role of IPO8 on nuclear import of miR551b, we overexpressed miR551b-3p or control miR in the cells that were pre-transfected with si-control, si-IPO8 or si-IPO9, then isolated miR551b-3p from the nuclear extract and performed qPCR to determine the enrichment of miR551b-3p in the nucleus. We used IPO9 as a control to confirm if there is specificity between the interaction of miR551b-3p with IPO8. This assay demonstrated that the loss of IPO8 expression but not the loss of IPO9 reduced the enrichment of miR551b in the nuclear fractions of cells, that were transfected with miR551b (Figures–4H and S5C to S5D). In conjunction with our qPCR assays in Fig–4H, our immunofluorescence assay also shows that the loss of IPO8 but not the loss of IPO9 disrupted the translocation of miR551b-3p to the nucleus (Figures–4I and 4J). Next, we determined the interaction between miR551b-3p and importin-8 by assessing the co-localization of Cy-3 labelled miR551b-3p with IPO8 in immunofluorescence assay and found that miR551b-3p co-localized with IPO8 in the cytoplasm (orange) and in the nucleus (cyan) (Figure-S5E). Previous studies have shown that mature microRNA interact with AGO1 protein in the cytoplasm during the maturation of microRNA (Eulalio et al., 2008; Li et al., 2017). To determine if AGO1 acts as an adaptor protein to connect IPO8, we have performed immunofluorescence and found that AGO1 interacts with IPO-8 as evidenced by the co-localization in both cytoplasm (orange) and nucleus (cyan) (Figure-S5F).

Next, we performed the rescue experiment, where we introduced the miR551b-3p expression in the miR551b-KO Hs578T cells, which were pre-transfected with IPO8 siRNAs or control siRNAs to prove the exogenous miR551b requires IPO8-mediated nuclear translocation to upregulate STAT3 expression. In this assay, we found that the gain of expression of miR551b rescued the proliferation and spheroid forming ability of miR551b-KO-Hs578T cells, which was disrupted by the loss of miR551b (Figure S6G and S6H). Importantly, the knock down of importin-8 (IPO8) but not the IPO-9 abrogated the nuclear translocation of miR551b and miR551b -induced STAT3 induction and subsequent increase in proliferation and spheroid forming ability of miR551b-KO-Hs578T cells, which was disrupted by the loss of miR551b (Figure S5G to S5K). Taken together, our results demonstrate that the interaction of IPO8 to miR551b-3p-AGO complex translocate to the nucleus and the sequence complementarity between miR551b-3p and STAT3 promoter allows the binding of miR551b-3p on STAT3 promoter. Importantly, this interaction of miR551b-3p with STAT3 promoter improve the occupancy of TWIST1 transcription factor and RNA-Pol-II to the transcription initiation site for STAT3 transcription (Figure–4K).

STAT3 is Required for miR551b-3p Induced Expression of OSM Gene Module

STAT3 regulates the expression of various interleukins and cytokines (Rosen et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2014). To further interrogate if STAT3 is critical for the expression of the OSM gene module, we transfected miR551b-3p into breast cancer cells that had been transfected separately with two different STAT3 siRNAs. We then quantified the expression of the OSM and IL31 chemokines and their receptors by qPCR, and western blotting (Figure–5A to 5C). Importantly, our results showed that loss of STAT3 expression abolished miR551b-induced OSMR, IL6ST, and IL31RA at both the transcript (Figure–5A) and protein level (Figure–5B). Because OSM and IL31 can potentially interact with OSMR after dimerizing with IL6ST or IL31R, we used qPCR to determine the effect of the miR551b-STAT3 axis on OSM and IL31 mRNA expression using total RNA isolated from the breast cancer cells that were pre-transfected with STAT3 siRNAs prior to miR551b-3p transfection. Our results showed that loss of STAT3 abolished miR551b-induced increase in the expression of OSM and IL31 in both MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cell lines (Figures–5C and S6A).

Figure-5. b-3p requires STAT3 for the regulation of OSM-Gene module.

A, MDA MB231 cells were transfected with con. miR or miR551b-3p, 24h after transfection of two different STAT3 siRNAs. RNA was isolated 48h after transfection and qPCR was performed to quantitate the expression of indicated mRNAs. mRNA expression was normalized to β-Actin. Bars represent S.E of triplicates. P-value was determined by Student’s t test. B, Immunoblot was performed using the lysates prepared from (A). C, qPCR was performed to quantitate the mRNA expression of OSM and IL31 from cells co-transfected with that siSTAT3 and miR551b as indicated in (A). Error bars represent means ± SE from three different experiments performed in quadruplicates. D-E. ChIP-qPCR analysis of the enrichment of STAT3 at the indicated promoter genes in MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with con. miR and miR551b-3p (D) or treated with OSM (20ng/ml) and IL31 (20ng/ml) (E). The qPCR data are presented as fold enrichment compared to IgG control. Bars represent mean ± S.E. Statistical analysis was done by Student’s t test.

To investigate whether miR551b induces STAT3-mediated transcription of OSM family genes, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), targeting STAT3 protein. This approach showed that miR551b-3p treatment enriched STAT3 on promoters of the OSM gene module, including the promoters of OSMR, OSM, IL31RA, IL31, and IL6ST (Figure–5D and Figure-S6B). To confirm that OSM and IL31 use a feedforward mechanism to activate the signaling pathway initiated by STAT3 protein, we stimulated MDA-MB-231 cells with OSM and IL31 and performed ChIP, targeting STAT3. The results demonstrated that OSM and IL31 stimulation enriched STAT3 transcription factor in the promoters of OSM, OSMR, IL6ST, IL31, and IL31R compared to untreated controls (Figures–5E, S6C). This result supports the notion that chemokines such as OSM or IL31 produced by STAT3 could activate STAT3 for prolonged periods contributing to transcription of OSM, OSMR, IL6ST, IL31, and IL31R. Thus miR551b-3p-mediated activation of STAT3 promotes transcription of OSM gene module, more importantly, for autocrine regulation of OSM family gene expression.

miR551b-3p Effectors Promote Oncogenic Effects in Immortalized Breast Epithelial and TNBC Cell Lines

As our data implied that OSM and IL31 are effectors of miR551b-3p in cancer, we next determined their effects on MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. OSM or IL31 stimulation significantly increased cell proliferation (Figure–6A) and the combination of OSM or IL31 enhanced proliferation modestly compared with either OSM or IL31 alone (Figure–6A). OSM and IL31 also promoted colony formation by breast cancer cells (Figure–6B) and their combination was more effective than either ligand alone (Figure–6B). OSM or IL31 promoted wound healing and migration and invasion of tumor cells, with the combination being more effective than either mediator alone (Figure–6C and 6D). To further determine whether OSM and IL31 promote autocrine signaling and STAT3 activation, we stimulated MDA-MB-231 cells with each ligand. Importantly, OSM and IL31 induced phosphorylation of STAT3 (Y705). We also noticed that OSM or IL31 treatment increased protein levels of unphosphorylated STAT3, IL31RA and OSMR (Figure–6E). Consistent with our finding that OSM and IL31 promote a migratory phenotype of breast cancer cells, we found that OSM or IL-31 treatment promoted mesenchymal characteristics of breast cancer cells, as evidenced by increased mRNA expression of vimentin and reduced expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin (Figure–6F). Our qPCR also showed that OSM or IL-31 treatment upregulated the expression of CD44 and reduced the levels of CD24, which are characteristics of tumor-initiating breast cancer cells (Figure–6F). Together, our results support the notion that the signaling of OSM and IL31 through OSMR and IL31RA are important for STAT3 expression and activation, which could contribute to proliferation, clonogenic capacity, EMT, and tumor initiating capacity.

Figure-6. b effectors associate with the progression of breast cancer.

A, MDA-MB-231 cells were stimulated with OSM (20ng/ml), IL31 (20ng/ml) or both at 10ng/ml of each and the cell viability was assessed at indicated time points using MTT assay. Error bars represent S.E of quadruplicates. *P<0.05. B, Colony forming ability of MDA-MB-231 cells treated with OSM or IL31 or their combination as in (A) was assessed on 14th day after treatment. Colonies were stained using crystal violet and photographed. Bar graph shows the OD of crystal violet eluted from the colonies measured at 560nm. C, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated as in (A), and the wound healing capacity was monitored at indicated time points. Red line indicates the empty space between healing cells. Scale bars represent 500 μm. D, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated as in (A), and the invaded or migrated cells through matrigel coated or non-coated trans-well inserts were monitored and photographed. Scale bars represent 500 μm. Bar graph shows the OD of the crystal violet eluted measured at 560 nm. E, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with OSM and IL31. Lysates were prepared at indicated time points and immunoblot was performed using indicated antibodies. F, Total RNA was isolated 48h after the treatment of chemokines as in (E) and qPCR was performed to quantitate the expression of indicated genes. mRNA expression was normalized to β-Actin. Bars represent mean ± S.E. Statistical analysis was done by Student’s t test. G-J, OSM-family gene transcripts were quantitated in the primary tumors versus normal breast tissues collected from mammoplasty reduction surgery. P-values were determined by Wilcoxon test. K-L, OSM and IL31 transcripts were quantitated in the normal breast tissues, Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive breast cancers (IBC). P-values were determined by Student’s t-test. Due to low sample numbers in the normal group, we excluded normal group from our analysis. M, OSM expression in different molecular subtypes of breast cancer in the TCGA dataset plotted using UALCAN portal (Chandrashekar et al., 2017). N, Kaplan–Meier analysis of ER-Negative breast cancer patients whose samples were stratified as high vs. low based on median expression of OSM (226621_at) using KM survival analysis plotter (Gyorffy et al., 2010).

The Oncostatin Gene Module Associates with Breast Cancer Progression

To determine if the OSM gene module is important for the pathobiology of breast cancer, we determined the expression of OSMR, OSM, IL31, IL6ST, and STAT3 in normal breast tissues collected from reduction mammoplasty and in breast tumor tissues in a published breast cancer dataset (Quigley et al., 2017). Strikingly, our analysis show that STAT3, IL31, and IL6ST transcripts are highly and significantly expressed in breast tumor tissues compared with normal tissues (Figures–6G to 6I), while the increase in OSM in tumor samples approached significance (Fig–6J). We also determined the expression of OSM and IL31 transcripts in a published mRNA data set of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive breast carcinoma (IBC) (Aure et al., 2017; Lesurf et al., 2016). As expected, OSM and IL31 were more highly expressed in IBC samples than in DCIS (Fig–6K and 6L). Furthermore, our analysis of TCGA data set using the UALCAN portal showed that OSM is highly expressed in the TNBC subtype compared to other molecular subtypes of breast cancer (Chandrashekar et al., 2017) (Figure–6M) and OSM is highly expressed in primary breast tumor tissues compared to the normal tissue (Figure-S6D). Importantly, our outcome analysis based on the expression of OSM, using the KM plotter survival analysis portal (Gyorffy et al., 2010), demonstrated that high levels of OSM in the estrogen receptor (ER)-negative patient cohort is associated with poor outcomes (Figure–6N). In contrast, OSMR expression did not vary markedly among the molecular subtypes of breast cancer (data not shown), whereas IL31RA is highly expressed in the primary breast tumor tissues compared to the normal breast tissues and IL31RA is highly expressed in TNBC subtype compared to other molecular subtypes (Figures-S6E and S6F).

Silencing miR551b-3p Inhibits Tumor Growth in an Orthotopic Breast Cancer Model

We next used an orthotopic mouse model of breast cancer to explore the therapeutic potential of targeting miR551b-3p to inhibit breast cancer growth. After encapsulating anti-miR551b-3p or control anti-miR into neutral nanoliposomes (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphotidylcholine-DOPC), we injected them intraperitoneally into athymic female nude mice bearing MDMB231 breast cancer cells orthotopically (Figure–7A). Importantly, this treatment reduced tumor growth, total tumor weight, and tumor volume (Figures–7B to 7D). As expected, anti-miR551b-3p also reduced the expression of miR551b-3p (Figure–7E) and key effectors, including STAT3, OSMR, and IL6ST (Figures–7F and 7G). In conjunction, the treatment with anti-miR551b-3p reduced the expression of cellular proliferation marker Ki67 and upregulated the levels of apoptotic marker cleaved caspase-3 in vivo (Figure–7H). We also noticed that anti-miR551b-3p decreased the levels of vimentin and N-cadherin; and increased the levels of E-cadherin in tumor tissues and reduced secreted levels of OSM and IL31 (Figures- 7G and 7I). It is noteworthy that the delivery of anti-miR551b-3p encapsulated in neutral nanolipsome did not make any unfavorable toxic effects in mice as indicated by significant changes in the levels of serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), loss in body weight or toxicity induced damages in kidney, liver, lung heart, brain and spleen, (Figures S7A to S7D).

Figure 7. Therapeutic targeting of miR551b-3p reduces breast cancer cell growth in vivo.

A, Schema of the experimental design and treatment schedule for in vivo study. MDA-MB-231 cells (2×106 cells/animal) were injected into the mammary fat pad of female athymic nude mice (age: 4 to 6 weeks, n = 7/group). Mice were treated with control (Con.) anti-miR or anti-miR551b-3p incorporated in DOPC nanoliposomes twice weekly until any of the mice became moribund. B–C, Tumors were isolated at the end of the experiments, representative tumors were photographed, and tumor weight quantitated. D, Tumor volume calculated twice in a week up to the end of the experiments (6.5 weeks). Bars represent SE of seven mice per group. *P < 0.05 determined by Student’s t-test compared between respective time point. E–F, Total RNA was extracted from tumor samples (n=3) from each group and qPCR was performed to quantitate the expression of miR551b-3p and the effector genes. miR551b-3p expression was normalized to U6 RNA and the mRNAs were normalized to ß-actin, respectively. G, Representative tumor tissues from four different mice were isolated, lysed, and immunoblotted. H, Representative H&E and immunohistochemistry analysis using tumor tissues from (A) were performed. Scale bars represent 150 μm. Bar graph represents the percentage of Ki67 and cleaved caspase-3 in the indicated groups. Error bar indicates the SE from mean value calculated from five random fields. I, Serum samples collected from the blood from each group at the end of experiment and ELISA was performed to determine the levels of OSM and IL31. Bars represent SE and P values were determined by Student’s t test. J, Model depicts how miR551b-3p-STAT3 axis activates the feedforward signaling through IL31 or OSM for tumor growth, cancer stemness, and EMT.

To further determine the effects of anti-miR551b-3p we observed due to the specific inhibition of miR551b but not through other non-specific targets, we prepared MDA-MB-231 cells stably knockdown of miR551b using small hairpin loop expressing anti-miR sequences or scrambled sequences and selected clone#3, in which miR551b expression is reduced more than 90% compared to the control for further studies (Figure-S8A and S8B) and also reduced the sphere forming capacity of MDA-MB-231 cells ~90% consistently in the serial dilutions (Figure-S8C) along with loss of characteristics of cancer stem cell markers evidenced by the loss of expression of CD44 and c-KIT and gain in the levels of CD24 (Figure-S8D). Next, we determined if the effects of anti-miR551b-3p we observed through the loss of miR551b-3p, using the MDA-MB-231-control-shRNA cells or MDA-MB-231-sh-miR551b-3p cells in 3D culture model and in vivo model. In our 3D culture assay, we found that the stable knockdown of miR551b-3p in MDA-MB-231 cells reduced the size and number of 3D colonies in matrigel significantly. We also found that the transfections of anti-miR551b-3p reduced the cell viability, spheroid size and number of 3D colonies of MDA-MB-231-sh-control-miR cells. In contrast, transfections of anti-miR551b-3p in MDA-MB-231-sh-miR551b cells, did not have any effect on the cell viability, spheroid size and number of 3D colonies and miR551b-3p expression in miR551b-3p stable knockdown cells (Figure-S8E to S8G).

Next, we employed the orthotopic breast cancer model, in which we injected the MDA-MB-231 control cells or MDA-MB-231-sh-miR551b (miR551b stable knockdown) cells in the mammary fat pad of nude mice. After a week, mice were injected with control anti-miR or anti-miR-551b-3p encapsulated in nano-liposome twice in a week for 7 weeks (i.p.) in the mice bearing control MDA-MB-231 tumors or MDA-MB-231sh-miR551b-3p tumors. In conjunction with our results in 3D culture model, we found that the loss of miR551b-3p using sh-RNA vector reduced the tumor growth more than 70% and reduced the tumor volume on 5th week onwards until the termination of the study ~80% as compared to the group of mice bearing MDA-MB-231-control-shRNA cells. Importantly, we noticed that the delivery of anti-miR551b-3p in the group of mice bearing MDA-MB-231-control-shRNA reduced the tumor growth ~60% and reduced tumor volume on 5th week onwards until the termination of the study ~70%, which is comparable to the genetic loss of miR551b-3p using sh-RNA vectors. In contrast, we did not find any effect on tumor growth or tumor volume by the delivery of anti-miR551b-3p encapsulated nanoliposomes in the mice bearing MDA-MB-231-sh-miR551b tumors (Figures-S9A to S9D). While the treatment with anti-miR551b-3p reduced the expression of cellular proliferation marker Ki67 and upregulated the levels of cleaved caspase-3 in the mice bearing MDA-MB-231 sh-control tumors; anti-miR551b-3p did not make any significant change in the levels of Ki67 and cleaved caspase-3 in the group of mice bearing MDA-MB-231sh-miR551b-3p tumors (Figure-S9E). Taken together, our results demonstrate that the ant-tumor effect of anti-miR551b mediated is not through any other targets other than specific inhibition of miR551b.

Discussion

Studies have shown that different cancer cells rely on unique growth and survival requirements that are acquired through distinct subsets of genomic alterations. While the roles of protein-coding genes in cellular signaling and autocrine loops are well established, the roles of non-coding RNAs and microRNAs as fine-tuners of cellular signaling are less well understood. Our data demonstrate that miR551b-3p located in 3q26.2 locus, provides growth and proliferative advantages to cancer cells. In contrast to the proliferative phenotypes, malignant tumors express high levels of mesenchymal genes, which increase the ability of tumor cells to invade and metastasize. In addition to the proliferative effects, miR551b-3p, and its effector OSM gene module, and STAT3 transcription factor induce several molecular switches that could contribute to the migration and invasion of breast cancer cells.

We found that mature miR551b-3p translocates from the cytoplasm to nucleus with the aid of IPO8 to interact with STAT3 promoter. This interaction of miR-551b-3p with STAT3 promoter is important for the recruitment of RNA-Pol-II and TWIST1 transcription factor to the transcription initiation site (Figure–4K). Our data suggest that the tumor cells express both high levels of IPO8 and miR-551b-3p expresses high levels of STAT3, thus RNA activation mechanism is an important tool in tumor cells for persistent activation of STAT3 signaling. STAT3 is considered to be a master transcription factor with roles in many physiological processes such as inflammatory signaling, aerobic glycolysis, and immune suppression (Masciocchi et al., 2011). Constitutive activation of STAT3 has been reported in various cancers (Rosen et al., 2006), thus STAT3 could be exploited as a target for cancer therapy in the patients, whose tumors express high levels of miR551b-3p. However, the upregulated levels of STAT3-like master transcription factors, often leads drug resistance to therapeutic regimens, which adversely affects patient’s outcome (Carmo et al., 2011). Recent developments in the small molecule inhibitors yielded into new generation STAT3 inhibitors like PG-S3–001 which is derived from the SH-4–54 class of STAT3 inhibitors as well as inhibitors like SF-1–066, BP-1–102, and BP-5–087 demonstrated superior pharmacokinetic properties for cancer therapy and treatment without severe toxicity and off target effects (Arpin et al., 2016; Ball et al., 2016). However, the therapeutic efficacies of these compounds are yet to be characterized for breast cancer treatment.

We found that STAT3 activates the oncogenic signaling through OSM gene module, which consists of the ligands OSM and IL31 as well as their receptors OSMR and IL31RA, which enhances the robustness of STAT3 signaling in TNBC cells (Figure–7J). We have previously shown that the growth factors epidermal growth factor (EGF) and neuregulin-1 (NRG-1) promote the transition of DCIS like structures to invasive structures in 3-D culture of MCF10A cells (Pradeep et al., 2012a; Pradeep et al., 2012b). Overexpression of growth factor family genes or their mutations are important mechanisms for aberrant activation of growth factor signaling, which enhance the robustness of oncogenic signaling (Amit et al., 2007b). Experimental and clinical data indicate that DCIS can progress to invasive disease; however, the mechanism of DCIS progression to invasive cancer is not well understood. Our in vitro and clinical data supports the notion that upregulated levels of OSM and IL31, which are mediated by miR551b-3p, not only promotes the proliferation of tumor cells, which also facilitate the transition of tumor cells towards mesenchymal traits for invasion and metastasis.

While it is possible to classify cancers based on their gene expression patterns into different subsets, a major challenge lies in identifying druggable pathways or gene modules in those subtypes. In this regard, we propose that targeting OSM gene module will be effective approach to treat a subset of patients, whose tumors express miR551b-3p or STAT3 or both. The OSM signaling module we identified as the downstream effect of miR551b-3p, is comprised of ligands (OSM and IL31), their receptors (OSMR, and IL31RA), and the STAT3 transcription factor are regulated through an autocrine mechanism (Figure–7J). Emerging evidences suggests that OSM is a pivotal component in the tumor microenvironment (TME) to promote EMT and epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity (E–M plasticity) and the acquisition of CSC properties (Smigiel et al., 2018). This study has shown that the generation of cells with mesenchymal and cancer stem cell properties was unique to OSM as implicated by robust activation of two key oncogenic effector proteins STAT3 and ZEB1, which was not observed following IL6 exposure in cancer cells. Compatible with the above findings, our results demonstrate that OSM induces the activation of STAT3 transcription factor for prolonged period, which again suggest that OSM and its receptors are critical for persistent oncogenic signaling for EMT, E–M plasticity and the acquisition of CSC properties.

Signaling modules are often conceptualized as linear events; however, the key regulators in each module are interconnected with other modules to form complex functional networks, which are critical for oncogenic events including cell growth, proliferation, migration, and metastasis (Chang et al., 2009; Kholodenko et al., 2010). A critical challenge remaining in cancer biology is to identify the key regulator in signaling modules, which are critical for tumor growth and metastasis. We are employing RNA interference (RNAi) approaches to target and inhibit the components of miR551b-3p or OSM gene module to inhibit the progression of breast cancer. Many of nano-liposome encapsulated RNAi strategies have entered in the clinic trials for a number of cancers (Tatiparti et al., 2017), suggesting that targeting miR551b-3p with anti-microRNAs warrants further exploration as a novel therapy to inhibit STAT3 and OSM signaling module in breast cancer.

STAR * METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

This study did not generate new unique reagents. Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Pradeep Chaluvally-Raghavan (pchaluvally@mcw.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice-

Female athymic nude mice (CrTac: NCr-Foxn1nu, Taconic Laboratories, RRID: IMSR_TAC:ncrnu), approximately 4 to 6 weeks old were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in accordance with guidelines and therapeutic interventions approved by by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the Medical College of Wisconsin. MDA-MB-231 cells (2 × 106 cells/mouse) were trypsinized, washed and resuspended in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) and 50μl was injected into each mice orthotopically. For injecting stable knockdown of miR51b-3p, MDA-MB-231-shControl miRNA and MDA-MB-231-shmiR551b-3p cells- (2 × 106 cells/mouse) were trypsinized, washed and resuspended in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) and injected into mice orthotopically in mammary fat pad. For both studies, as a therapeutic approach, MDA-MB-231 tumor cells or MDA-MB-231 shmiRNA tumor bearing mice were randomly divided in two groups (n = 7/group) after seven days of tumor cell injection and treated with (150 μg/kg body weight) control anti-mirRNA or anti-miR551b-3p (encapsulated in neutral DOPC nanoliposomes) in 100μl PBS intraperitoneally twice in a week as indicated. Treatment continued for 7 weeks, at which point, all mice were sacrificed, necropsied, and tumors harvested. Treatment continued for 7 weeks, at which point, all mice were sacrificed, necropsied, and tumors harvested. Tumor volume was measured every week using caliper throughout the experiment and tumor volume was calculated using the formula (Width2× Length)/2. Tumor tissue was prepared as snap frozen for lysate preparation for RNA and protein isolation or fixed in 10% formalin for immunohistochemistry. Blood collected and 100 μl of serum prepared for cytokine ELISA.

Cell Lines-

The human breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231, HCC-1806, MDA-MB-436, T47D, ZR-75–1, BT474 and MCF10A were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), MCF-7 was obtained from The European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC-Sigma Aldrich), OVCAR8 was obtained from National Cancer Institute (NCI) and SUM-149 was obtained from BioVT (Westbury,NY). Hs578-WT and Hs578-miR551b-3p-KO cells were provided by Synthego Corporation, CA. All cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, GA, USA). MCF10A cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 1: 1 media (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) with 5% horse serum (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), EGF (20 ng/mL), Hydrocortisone (0.5mg/mL), Cholera Toxin (100ng/mL) and Insulin (10 μg/mL). All cell media was supplemented with 100 IU/ml penicillin-streptomycin and maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 as described previously (Pradeep et al., 2012b). Cells were routinely tested and deemed free of Plasmotest™ Mycoplasma Detection Kit (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA). Authenticity of the cell lines used were confirmed by STR characterization at IDEXX Bioanalytics Services (Columbia, MO).

METHOD DETAILS

miRNA transfections

Control miRNA, miR551b-3p mimics, control antimiR and anti-miR551b-3p were obtained from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). Mature sequences of the miRNAs used in this study are as follows: miR551b-3p: 5’-GCGACCCAUACUUGGUUUCAG-3’; control miR: 5’-UCACAACCUCCUAGAAAGAGUAGA-3’; and mutated miR551b-3p: 5’-GCGUGGGAUACAACCUUUCAG-3’. Briefly, 1× 106 cells (100 cm dish) or 1 × 105 cells (35 mm3 well plate) were seeded for miRNA transfections and transfected and transfected using Dharmafect transfection reagent (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) following the manufacturer’s instructions at a final concentration of 3–7 nM for 48 h. Control miRNA or control anti-miRNA was transfected at a concentration of 7 nM. Each transfection experiment was independently repeated at least in triplicates.

siRNA transfection

1× 104 cells (100cm dish) were transfected with scrambled (7 nM) or non-overlapping siRNA sequences (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) (7 nM) listed as below using the RNAiMax transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA), according to manufacturer’s protocols.

| Gene Symbol | Sequence#1 | Sequence#2 |

|---|---|---|

| STAT3 | 5’GAGAUUGACCAGCAGUAUA3’ | 5’CAACAUGUCAUUUGCUGAA3’ |

| IPO8 | 5’GUGUCAUGCAGCUAAACUU3’ | 5’CAAUUGCUGCCUUGUACUA3’ |

| IPO9 | 5’CAAACCUGCUCUAGAGUUU3’ | 5’CAUCAGUCAUCUUGAAACA3’ |

Generation of miR551b-3p knockdown using shRNA

To establish the stable knockdown of miR-551b-3p in MDA-MB-231 cells, we transfected the cells with pEZX vector control or pEZX vector expressing miR-551b-3p inhibitor (GeneCopoeia, Rockville, MD) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were selected 48h after transfection to ensure that the cells were stably incorporated with control scrambled sequences or miR-551b-3p inhibitor using puromycin (8 μg/ml) containing culture media for one week. Total RNA was isolated, and qPCR was performed to determine miR551b expression.

Generation of miR551b-3p knock out cells using CRISPR/Cas9 vectors

CRISPR/Cas9-Edited miR551b-knockout Hs578T breast cancer cells were prepared by Synthego Inc (Menlo Park, CA, USA). The following sgRNA sequences UCUAACAGAGGUCUGAAGUC, AAGUCCUGCAUAAACAUAAA and 2NLS Cas9 nuclease were used for the generation of miR551b-KO cells.

HS578T were electroporated with the sgRNA complex, composed of 6 μg of Cas9 and 3.2 μg sgRNA, using the P3 Cell 4D-Nucleofector® X Kit in Amaxa 4-D device (Lonza, Alpharetta, GA, USA). 2×105 cells per condition were electroporated in separated strip wells using program EO-100 and DZ-100. Cell viability was determined 24h after transfection. Deletion of miR551b in Hs578T cells was validated by Synthego via Sanger sequencing of the PCR amplified edited fragment using the primers F: CCCCTGAGTTATATTTGCTGGTTCTTAC

R: CCCATTGGAACAGAAATGCAATATAATC and gel electrophoresis after extracting the genomic DNA. Sequencing data was analyzed using ICE V2 CRISPR analysis software tool (Synthego, Menlo Park, CA).

Cell proliferation and cell viability assay

To measure cell proliferation, MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells were plated at a density of 1 × 104 cells in 96 well plates and were treated with OSM (20 ng/mL), IL31 (20 ng/mL) or combination of OSM and IL31 (each 10 ng/mL) (R and D systems, Minneapolis, MN). Cell were trypsinized, stained with Trypan Blue (Sigma Aldrich, MO, USA) and counted after 0 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h using TC10 automated cell counter (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). To measure cell viability, MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells were plated at a density of 1 × 104 cells in 96 well plates after transfection of control miRNA or miRNA mimics and/or miRNA inhibitor. 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reagent (Sigma Aldrich, MO, USA) were added and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. This was followed by dissolving formazan crystals with acidic isopropanol. Absorbance was measured in microplate reader (Tecan, Mannedorf, Switzerland) at 560nm.

Colony formation assay

MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells at densities of 400–1200 cells per well were seeded in 6-well plate following transfection with Control miRNA/miR551b-3p or treatment with OSM or IL31 and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 14–21 days to allow colony formation. Cells were rinsed with PBS, fixed in 5% glutaraldehyde for 10min and then stained with 1% crystal violet (Sigma Aldrich, MO, USA) for 20 min. Plates were washed with water and dried before scanning. Crystal Violet was solubilized with 10% acetic acid and quantified by reading absorbance at 560 nm.

Wound healing assay

For wound healing assay, the cells were grown to confluence and wounded using 200 uL pipette tip in a 35mm3 culture dish. The wound closure was visualized by time-lapse imaging using a phase contrast microscope (Nikon, Fukok, Japan) coupled to a CCD camera. Phase-contrast images of three to five selected fields were acquired for at least 24 h. Images were analyzed using Image J software.

Migration and invasion assay

The effect of miR551b on cellular motility was analyzed by carrying out cell migration and invasion assay as described earlier (Jagadish et al., 2015). In brief, for migration assay, miR551b transfected MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells (1 × 105 cells) were seeded on the upper chamber of the Boyden chambers trans-well inserts (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA). Growth medium containing 10% FBS was the chemoattractant in lower chamber. For invasion assay 2 × 105 cells were seeded in triplicate (n = 3) to the Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA) coated inserts, or to the uncoated inserts as control. Cells were also treated with OSM and IL31 after seeding for migration and invasion assays for indicated times. Migration and invasion assays were performed in the presence of cell cycle inhibitors mitomycin C (5 μg/ml), in the trans-well chambers as described before (McCarroll et al., 2004; Pullar et al., 2003). Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 12 h for migration assays and for 16h for invasion assays. Cells that did not migrate through the pores were removed using a cotton swab and inserts were washed and stained with 0.5% crystal violet in 20% methanol for imaging. Alternatively, stained membranes were dissolved in 10% acetic acid, and quantified in microplate reader at 560 nm.

3-Dimensional (3-D) culture of tumor cells and Limiting Dilution assay

Tumor cells were cultured as 3-D spheroids as described previously (Pradeep et al., 2012a; Pradeep et al., 2012b). For anchorage dependent culture, 3 × 104 cells were suspended in growth factor reduced Matrigel purchased from BD Biosciences (Bedford, MA, USA) supplemented with growth enriched media-DMEM/F12 1: 1 media (Gibco) with 5% horse serum (Gibco), EGF (20 ng/mL), and supplemented with 100 IU/ml penicillin-streptomycin and maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 (1:1 Matrigel/medium in a total volume of 250 μL). Cells were then cultured in complete medium up to two weeks based on the requirement and replenished with 1:1 Matrigel/Media every two days. For in vitro limiting dilution assay, spheroid cultures from MDA-MB-231 cells stably knockdown with shmiR551b and shcontrol miRNA were suspended as mentioned previously at 1, 10, 100, 1000, 10,000 cells per well. For anchorage independent culture, MDA-MB231 cells at a density of 3 × 104 cells were suspended in 24 well low adherent plate in DMEM containing complete media following transfection with control miRNA and miR551b-3p as mentioned previously.

Flow cytometry

Apoptosis was detected using a Calcein AM/EtBr based Live/Dead cell viability Kit (Molecular Probes, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). MDAMB-231 cells were plated at optimal densities and transfected with Control anti-miR and anti-miR551b. After transfection, supernatants from each treatment group were collected and trypsinized to single cell suspension. Trypsinized cells were washed with PBS, pelleted, re-suspended in Ca2+ and Mg2+ free PBS, and counted. The 5 × 10 6 cells were resuspended in PBS and incubated with 50 μM Calcein AM and 2mM EtBr for 20 min according to manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, cells were strained to single cells into 5 mL polystyrene round-bottom FACS tubes (BD Falcon), placed on ice, and processed on a BD LSR II Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) no longer than 1 h post-staining. The data was analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo LLC, Ashland, Oregon).

Reverse-phase protein arrays (RPPA)

RPPA analysis was performed as described previously (Chaluvally-Raghavan et al., 2016b; Hennessy et al., 2010) and detailed at the MD Anderson Cancer Center RPPA core facility as below: https://www.mdanderson.org/research/research-resources/core-facilities/functional-proteomics-rppa-core.html.

Briefly, cells were washed in ice-cold PBS, and lysed in 30 μL of RPPA lysis buffer [1% Triton X-100, 50 nmol/L HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 nmol/L NaCl, 1.5 nmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 100 nmol/L NaF, 10 nmol/L NaPPi, 10% glycerol, 1 nmol/L PMSF, 1 nmol/L Na3VO4, and protease inhibitor cocktail] for 30 minutes with frequent vortexing on ice, followed by centrifuging for 15 min at 14,000 rpm, and the supernatant were collected. Protein concentration was determined by Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with a BSA standard curve according to manufacturer’s protocol. 30 μL lysates were transferred into a 96-well PCR plate. To each sample well, 10 μL of SDS/2-ME sample buffer (35% glycerol, 8% SDS, 0.25 mol/L Tris-HCl, pH 6.8; with 10% β-mercaptoethanol) was added and incubated for 5 minutes at 95°C and then centrifuged for 1 minute at 2,000 rpm.

Samples were diluted serially and transferred into 384-well plates and heated at 95°C for 10 min. Approximately, 1 nL of protein lysate lysate was then printed onto nitrocellulose-coated glass slides (FAST Slides, Schleicher & Schuell BioScience, Inc., Keene, NH) with an automated robotic GeneTac arrayer (Genomic Solutions, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI) per array by pin touch. Each spot on the array slide represents a certain dilution of the lysate of a particular sample. Following slide printing, the array slides were blocked for endogenous peroxidase prior to the addition of the primary antibody, then treated with biotinylated secondary antibody (anti-mouse or anti-rabbit) was used as a starting point for signal amplification. Tyramide-bound horseradish peroxidase cleaves 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride, giving a stable brown precipitate with excellent signal-to-noise ratio. Signal intensity was captured by scanning the slides with ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) and quantified using the MicroVigene automated RPPA module unit (VigeneTech, Inc., North Billerica, MA). The intensity of each spot was calculated, and an intensity concentration curve was calculated with a slope and intercept using MicroVigene software.

Western blot and immunoprecipitation

Cultured cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). Lysates were vortexed five times at 5 sec interval and incubated on ice for 30 min, then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. Protein concentration was determined by Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with a BSA standard curve according to manufacturer’s protocol. About 25 μg of protein was separated with precast SDS-PAGE gradient gels (4–12%, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Membranes were probed with the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, then washed and probed with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h at room temperature. Chemiluminescence was detected using X-ray films.

For immunoprecipitation, nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extracts were prepared using Cell Fractionation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The lysates were pre-cleared with protein A/G magnetic beads (Thermo Fischer Scientific) for 1 h at 4oC with rotation, followed by incubating with IPO8 and Control IgG antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) coupled with protein A/G magnetic beads overnight at 4oC. The samples were then washed with lysis buffer and treated with 20 ug/mL RNase A (Thermo Scientific) for 15 min at room temperature with rotation. Subsequently, the protein-antibody conjugated beads were washed, and proteins were eluted in 2x SDS sample buffer (BioRad) at 95°C for 10 min. Cytoplasmic and nuclear cell lysates (Input) and immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred, and blotted as described earlier and analyzed with specific primary antibodies as indicated.

Northern Blotting

Total RNA from cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were isolated using RNA subcellular isolation kit (Active Motif) according to manufacturer’s instructions. TURBO DNase (Ambion) was used to digest if any DNA fragment exists in the RNA fractions. For endogenous expression, 1× 106 cells from various breast cancer cell lines were seeded for 24h and harvested. For shRNA and CRISPR-Cas9 KO, shControl miRNA and shmIr551b-3p, Hs578T-WT and Hs578T-miR551b-KO cells (1× 106 cells) respectively were seeded for 24 h and harvested. For co-transfection, 1× 106 MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded for 24 h and transfected with siIPO8 or siIPO9 for 24h followed by transfection with control miRNA or miR551b-3p mimic and harvested in cell lysis buffer after a total incubation of 48 h. RNA was isolated and nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA fractions were subjected to Northern Blotting using Highly sensitive miRNA Northern Blot Assay Kit (Signosis Inc., CA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. miR551b-3p, U6 (nuclear marker) and tRNA-lysine (cytoplasmic marker) probes were designed by Signosis Inc. For miRNA detection, northern blotting analysis was carried out using 5 μg of RNAs separated on 15% pre-run urea-polyacrylamide gel in TBE buffer and RNA were transferred onto nylon membrane. The membranes were hybridized with biotin-labeled RNA probes (containing complementary sequence of the miRNA and a tag sequence) overnight at 42°C with gentle rotation. To amplify the signal and detect the tag sequence membranes were incubated with an amplifier enriched with biotin molecules for 2 h. Subsequently, the membranes were washed extensively, blocked with blocking solution and further incubated with Streptavidin-HRP Conjugate. The membranes were subsequently incubated with chemiluminescence detection solution and exposed to X ray film.

ELISA

To determine the amounts of IL31 and OSM secreted by the cells and in the mouse serum, ELISA tests were performed. Cells were plated at 1 × 106 per 10-cm dish. At confluency following 48 h post miRNA transfections, or treatment with OSM or IL31, culture supernatants were harvested, centrifuged and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, and ELISA of OSM and IL31 was performed using Human OSM DuoSet ELISA and Human IL-31 DuoSet ELISA (R and D Systems, MN, USA) respectively according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Human-specific IL-31 and OSM recombinant protein (R and D Systems, MN, USA) were used as standards to determine the amounts of these cytokines present in the culture supernatants and serum. All assays were performed in triplicate and repeated three times independently.

RNA extraction

Cultured cells:

Total RNA and miRNA from cultured cells were extracted using RNeasy Plus kit and miRNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer’s guidelines. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and lysed by addition of RLT buffer provided in RNAeasy kit or Qiazol reagent, mixed thoroughly by pipetting several times and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. For miRNA, chloroform was added and mixed thoroughly, then centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 rpm, 4°C. The aqueous layer was removed, mixed with an equal volume 70% ethanol, and transferred to an miRNeasy spin column for RNA purification.

Xenografts:

Animal xenograft tumor tissues were harvested and snap frozen. 10 mg of tissue was homogenized using a handheld electric tissue homogenizer followed by Polytron in Qiazol reagent. Once homogenized, miRNA or mRNA was isolated using the Qiazol/Chloroform/Spin column purification protocol as described earlier.

mRNA qRT-PCR

Primer design:

qRT-PCR primers (Table S4) were designed by the primer design program Primer3Plus.

Reverse transcription:

1μg RNA was transcribed to cDNA using iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA) in a total volume of 20 μl.

qRT-PCR:

iTaq Universal SYBR Green PCR Kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA) was used for all assays and qPCR was performed in CFX Connect Real Time PCR system (Bio Rad, Hercules, CA). mRNA expression was normalized to β-Actin (ACTB) mRNA. The total reaction volume was 10 μL, including 10 μL 2X iTaq Universal SYBR Green mix, 10 μM left primer and 10 μM right primer, and 1 μL cDNA template. Each assay was performed in triplicate. Non template control (NTC) was added each time in all the assays. The PCR program started with 1 min. at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles (95°C, 30 s.; 57°C, 30 sec) and extension of 72°C for 2 min. The last steps of PCR are performed to acquire the dissociation curve and to validate the specificity of PCR amplicons.

miRNA qRT-PCR

Reverse transcription:

1μg total RNA was transcribed to cDNA using miScript HiSpec Buffer in miScript Reverse transcription II kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) in a total volume of 20 μL following the manufacturer’s protocol.

qRT-PCR:

mature miRNA qRT-PCR reactions were performed as described previously (Chaluvally-Raghavan et al., 2016b; Chaluvally-Raghavan et al., 2014) using miScript SyBr Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with primers for hsa-miR551b-3p (#000593) and small nuclear RNA U6 was used as endogenous control (#001973) (Qiagen) and negative controls without template were added in each plate. All qPCR was run in CFX Connect Real Time PCR system (Bio Rad, Hercules, CA) with the following cycling condition: 95°C, 15 min; 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C 15 sec, annealing at 55°C for 30 sec and extension at 70°C for 30 sec with a ramp rate of 1°C/sec. This was followed by a default dissociation curve to validate the specificity of PCR amplicons.

Luciferase Reporter Assay

For luciferase assay, 2×104 MDA-MB-231 cells were plated in 96-well plates 24 h prior to transfection. For each well, 100 ng of wild type (WT) STAT3 promoter or mutant STAT3 promoter cloned in Renila Luciferase reporter vector pLight (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) was co-transfected along with 7 nM control miRNA or miR551b using Lipofectamine 2000. Renilla luciferase activity was measured using Dual-Glo luciferase Assay system (Promega) as mentioned previously (Chaluvally-Raghavan et al., 2016a) according to manufacturer’s protocol in triplicate at 48 h post transfection and normalized to firefly luciferase activity. MiR551b-3p reporter activity was normalized to empty vector control.

Immunostaining

Immunostaining was performed as described previously (Chaluvally-Raghavan et al., 2014; Pradeep et al., 2014). Briefly, MDA-MB-231 1×104 cells were grown on 35mm glass bottom dish (ibidi Fitchburg, WI, USA) transfected with Cy3 labelled miRNA for 48h then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in blocking solution (0.5% BSA in PBS) followed by blocking for 1 h with 0.5% BSA in PBS, and then stained overnight at 4°C with a primary antibody (1:150 dilution). After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor anti-mouse 488 and Alexa Fluor 568 Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (1:1000, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Glass slides were mounted using ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) containing DAPI. Each transfection was replicated independently three times. Images were acquired with a 40X objective using a Nikon confocal microscope. Z-stacked sections (10 to 22 slices) of the cells were captured with a motorized Z‐focus controlled camera. ImageJ software was used to reconstruct the images using the Z project plug-in.

RNA Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (RNA-FISH)

RNA-FISH was used to identify the nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of miR551b-3p in breast cancer cells. Oligonucleotide miR551b-3p probes labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) at their 5′-ends were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. The sequences of miR551b-3p probe and the scrambled control probe were 5′-[DIG]CTGAAACCAAGTATGGGTCGC-3′ and 5′-[DIG]AGTGTTGGAGGATCTTTCTCATCT-3′, respectively. 5 × 104 cells were plated in the glass center of 35 mm glass-bottom dishes (Cellvis, CA). Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and washed three times for 5 min with PBST at RT and processed for FISH as described previously with some modifications (Agarwal et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2018). Briefly, following fixation, acetylation solution (5 ml DEPC-treated water, 80 μL triethanolamine, 10.5 μL HCl (37%), 15 μL acetic anhydride) was added for 10 min and incubated for 7 min with TURBO DNase (Ambion) to digest any contaminating DNA at 37oC followed by quenching with 0.2% Glycine in PBS. The culture dishes were pre-incubated in prewarmed hybridization solution (50% formamide, 2× SSC buffer, 100 μg/ml yeast RNA, 1x Denhardt Solution, 10% Dextran Sulphate, 10mM EDTA, 0.01% Tween) for 2 h at 55°C. For each culture dish, the DIG probe was diluted with hybridization buffer and denatured by heating them up to 80°C for 5 min followed by quickly placing on ice. The probes were added onto the culture dish and hybridized at 65°C overnight followed by extensive washes with 0.1 × SSC buffer (Sigma Aldrich). Slides were incubated in RNAse A for 1 h at 37°C to remove unbound RNA and incubated in blocking solution (1% BSA in PBST) for 1 h, and then in anti-digoxigenin-FITC Fab fragments (Roche) for 1 h. After three washes, culture dishes were mounted in DAPI containing mounting media and observed in Nikon confocal microscope using a 60x objective lens. Z-stacked sections (10 to 22 slices) of the cells were captured with a motorized Z‐focus controlled camera.

RNA Immunoprecipitation Assay

RNA immunoprecipitation assay (RIP) was performed using Magna RIP™ RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation Kit (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Following nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction using Cell fractionation kit as mentioned earlier, lysates were incubated with respective antibodies coupled to Dynabeads Protein A/G for overnight at 4°C. Following extensive washes, the immobilized immunoprecipitated complexes were incubated with proteinase K 55°C for 30 min to digest the protein. Co-precipitated RNA and the Input (crude lysate) were eluted and purified with Trizol Reagent and analyzed by qPCR. The fraction of co-precipitated RNA is presented as fold enrichment.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

MDA-MB-231 cells were either treated with OSM (20 ng/mL) and IL31 (20 ng/mL) or transfected with control miR and miR551b-3p for 48h. ChIP was performed as previously described (Anjali et al., 2015) using ChIP assay kit (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA). In brief, formaldehyde fixed and 125 mM glycine neutralized cells were lysed with 5 mM PIPES pH 8, 85 mM KCl, 0.5% NP-40 with 20 mM sodium butyrate and protease/phosphatases inhibitors (2 mM PMSF, 20 mM NaF, 1X Aprotinin, 0.1 mg/mL Leupeptin, 2 mM Na3VO4) followed by sonication using a Bioruptor sonicator (Diagenode, Denville, NJ) to obtain chromatin fragments of 100–500 base pairs. Fragmented chromatin (200 μg) was incubated overnight with 5 μg STAT3 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-IgG (Santa Cruz) as negative control. Immune-complexes were coupled to Protein A beads and crosslinks were reversed (65°C for 12–16 h), and precipitated DNA was treated with Proteinase K and RNase A and then purified using QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Input and purified STAT3-ChIP-DNA was used in qPCR and 5% of the eluted DNA input was used in the Thermal PCR reaction Primers were designed for the putative STAT3-binding regions on promoters of OSMR, OSM, IL31, IL31RA, and IL6ST using DNA-star Lasergene 15.2 core suite (DNAstar, Madison, WI). IL8 promoter sequences with putative STAT3-binding was used a positive control. All the primers were designed using Primer-BLAST (NCBI, Bethesda, MD) and the primer sequences were included in Table-S4. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by real-time qPCR (Bio-Rad, Des Plaines, IL) as described earlier (Anjali et al., 2015). Fold changes were calculated using the ΔΔCt method, normalized to % input and presented as fold enrichment over control rabbit IgG.

Liposomal preparation