Abstract

Background:

Use of saliva as a specimen for detection of antibodies to infectious agents has generated particular interest in AIDS research community since 1980s. HIV specific antibodies of immunoglobulin isotypes IgA, IgG, and IgM are readily found in salivary secretions.

Aim and Objectives:

In the present study, HIV specific antibodies were detected in saliva and serum samples of HIV patients by ELISA in confirmed HIV seropositive patients and efficacy of saliva was established in diagnosis of HIV.

Methods:

The 100 saliva and serum samples were collected from age and sex matched confirmed HIV seropositive subjects and 100 Healthy Controls without any infections. HIV antibodies were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using Genscreen HIV 1/2 Kit.

Results:

The results were found to be 99% sensitive and 100% specific for saliva samples, while it was 100% sensitive and specific for serum samples.

Conclusion:

Saliva can be used as alternative to blood for detection of HIV antibodies as saliva collection is painless, non-invasive, inexpensive, simple, and rapid. Salivary antibody testing may provide better access to epidemic outbreaks, children, large populations, hard-to-reach risk groups and may thus play a major role in the surveillance and control of highly infectious diseases.

Keywords: Antibodies, HIV, saliva, serum

Introduction

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a disease caused by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection which emerged as a pandemic in the last three decades.[1] Approximately, 36.9 million people are living globally with this infection. India itself accounts for the third-largest number of HIV infected people in the world (around 2.1 million) after South Africa and Nigeria. However, UNAIDS (2018) data suggested a marked decrease in the number of new infections and AIDS related deaths by 27% and 56%, respectively, from the period of 2010-17. The same data also estimated HIV prevalence among adults in India (Aged 15–49 years) to be 0.2% in which, 79% of them were aware of their HIV status and 56% of them were on the anti-retroviral therapy (ART). In spite of this awareness against HIV, there were marked increase in the new infections to 88,000 from 80,000 and AIDS-related deaths to 69,000 from 62,000 in the year 2017; therefore, HIV infection is still a major health concern in India.[2] World Health Organization (WHO) and National AIDS control organization (NACO) in 1997 enumerated the different modes of transmission of HIV. These are sexual intercourse (anal/vaginal/oral) with an infected partner (man to woman, woman to man, and man to man), transmission with infected blood, blood products, organs, tissue transplantation and artificial insemination, contaminated syringes and needles, and from an infected mother to child, i.e. perinatal or vertical transmission. Worldwide, HIV is most commonly transmitted by sexual activity. HIV is found in blood and other body fluids including semen, vaginal fluid, and saliva. The immense majority of HIV infections are produced during unprotected sexual intercourse via the vaginal mucosa and especially the anal mucosa.[2,3] The risk of HIV transmission via oral secretion is an issue of growing interest to dental health professionals, above all with the upsurge in the number of infected individuals. Although HIV RNA, proviral DNA, and infected cells are readily detectable in salivary secretions and gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) of infected individuals, the transmission of HIV by oral route is very low or virtually non-existent. The mechanism of this oral immunity is poorly understood. Reports of antiviral activity in the saliva of both healthy individuals and HIV-infected individuals suggest the presence of a factor or factors in saliva that can inhibit HIV infection. Furthermore, it is well-established that human saliva inhibits HIV infectivity in vitro.[4,5,6,7] The anti-HIV inhibitory factors in saliva may make a major contribution to the extremely low or negligible rates of oral transmission of the virus reported by epidemiological studies.[1,4,5] Evaluation and diagnostic usefulness of saliva for detection of HIV antibody have been studied since 1986 as saliva is a body fluid containing antibodies of diagnostic significance. Unlike venipuncture, saliva collection is painless, non-invasive, inexpensive, simple, and rapid. By using sensitive immunoassays in salivary specimens, it is possible to diagnose immunoglobulins against a wide range of infectious diseases, e.g. hepatitis A, B, and C, measles, mumps, rubella, human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein Barr virus, parvovirus B 19, human herpesvirus 6, and Helicobacter pylori infections. Salivary antibody testing may provide better access to epidemic outbreaks, children, large populations, hard-to-reach risk groups and may thus play a major role in the surveillance and control of infectious diseases. Evaluation and diagnostic usefulness of saliva for detection of HIV antibody have been done by enzyme-linked immune assay (ELISA) which has been modified by increasing the specimen volume, altering the incubation periods, reagent concentrations, and reducing the assay cutoff values.[6,7,8,9] These modifications have resulted in improved ELISA sensitivity and specificity compared with those of matched serum test.

Material and Method

The total of 200 subjects, 100 HIV confirmed seropositive as study group and 100 age and sex matched healthy individuals who had undergone a checkup by a qualified medical physician as control group, were randomly selected for the study from the OPD of Dhiraj General Hospital SSG Hospital and Anti-Retroviral Treatment Center, K. M. Shah Dental College and Hospital Piperia, Vadodara and Non-Governmental organizations named Kirpa foundation working for HIV positive patient in Vadodara. The study was approved by Ethical Committee of Sumandeep Vidyapeeth, Vadodara years starting from January 2007–2010 with the approval of institutional research ethical committee SUVEC/ON/20/2007 (dated 20-08-2007). Written consent was obtained from each participant. The aim and objectives of the study were to detect HIV antibodies in saliva and serum of newly diagnosed confirmed HIV seropositive patients by ELISA and to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of ELISA test in serum and saliva samples of HIV positive and healthy individuals. Hence, for the study, the first step taken was to select a newly diagnosed confirmed seropositive patients before starting ART. Three separate positive ELISA tests were considered confirmatory as western blot, a confirmatory test, for HIV detection was not done for selected subjects due to its cost and unavailability for the confirmed seropositive patients who were selected for the study. Participants were excluded if they were on ART, had any history of autoimmune disorder, e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), and rheumatoid arthritis as such cases were likely to give false-positive results with ELISA test. Saliva collection and blood collection apparatuses were used which included whole saliva collector (50 ml); saliva collection was done by simple spitting method in isolation by making the patient sit comfortably without stimulating the salivary flow for a period of 2 min. For serum collection, tourniquet was used and forearm was cleaned with spirit and cotton and then with help of bi ended needles/connector, the blood was collected in vacutainer tubes—4 ml and 10 ml vials were used and then stored in cool icebox till transferred to microbiology lab for future test by ELISA for antibodies detection. For all this procedure, universal precautions were strictly used for collection, storage, and disposal of HIV positive patients’ samples.

Results and Observations

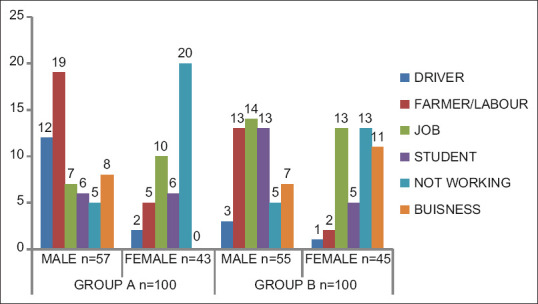

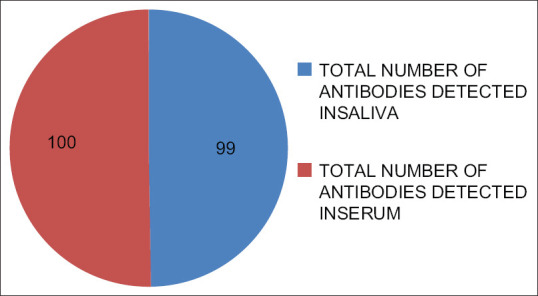

The age range for the study group was from 6 years to 65 years with mean age of 34.14 ± 11.51 years, whereas age range for control group was from 11 years to 62 years with mean age of 31.02 ± 7.15 years. The general sociodemographic data of the population revealed that most of HIV positive males were laborers (33.3%) and truck drivers (21%) by occupation, whereas most of HIV positive females were housewives (46.5%) [Figure 1]. The most common mode of HIV transmission in the study group was unprotected sexual practices (70%) followed by blood transfusion (18%), vertical transmission (9%), and intravenous drug use (3%) [Table 1]. Out of total 25 married females of study group, 21 (84%) had given history of single partner and 4 (16%) had multiple partners, whereas 3 (27.2%) out of 11 widows also gave history of multiple partners [Table 2]. Out of total 28 cases of sexual transmission of HIV infection, only 7 (25%) females gave history of multiple partners. Thus, the results indicated that total 95% married males and 16% married females of study group had unprotected sexual activities with multiple partners which indicates 84% females acquired HIV infection from HIV positive spouses [Table 3]. Out of total 100 subjects in study group, 99 (99%) were tested positive for HIV antibodies in saliva samples with one false negative result and all the subjects were detected positive for HIV antibodies in serum samples, whereas all the subjects of control group were tested negative for HIV antibodies in serum and saliva samples [Figure 2]. Thus, the ELISA test, which was performed using a specialized ELISA kit by BIORAD laboratories, GERAMANY (Genscreen HIV1/2) which had higher sensitivity to detect HIV antibodies, was found to be 99% sensitive and 100% specific for detection of HIV antibodies in saliva samples of study group, whereas it was found 100% sensitive and specific for detection of HIV antibodies in serum samples of study group as only one false-negative result was reported in saliva sample as compared with serum samples.

Figure 1.

Occupation status in study and control groups. It was seen that most of HIV positive males were laborers (33.3%) and truck drivers (21%) by occupation, whereas most of HIV positive females were housewives (46.5%)

Table 1.

Mode of transmission of HIV in subjects of the study group

| Mode of transmission | |

|---|---|

| Sexual | 70 |

| Blood transfusion | 18 |

| Vertical | 9 |

| I V drug users | 3 |

The most common mode of HIV transmission in the study group was unprotected sexual practices (70%) followed by blood transfusion (18%), vertical transmission (9%), and Intravenous drug users (3%).

Table 2.

Sexual activity of subjects in study group

| Males n=57 | Females n=43 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterosexual | Homosexual | Bisexual | Heterosexual | Homosexual | Bisexual |

| 56 | 1 | 1 | 43 | -- | -- |

Out of the 57 males of the study group, 56 were heterosexuals, 1 homosexual, and 1 bisexual. Out of 43, all females in the study group were heterosexuals. The results indicated that almost all of the males (98.2%) and females (100%) of study group were heterosexuals.

Table 3.

Marital status of males and females in study group

| Males (n=57) | Females (n=43) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | Unmarried | Divorced | Widow | Married | Unmarried | Divorced | Widow |

| 40 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 25 | 5 | 2 | 11 |

Out of the 57 males in the study group, 40 (70%) were married, 12 (21%) were unmarried, 4 (7%) divorced, and 1 (1.75%) widower, whereas out of 43 females, 25 (58.13%) were married, 5 (11.6%) unmarried, 2 (4.65%) divorced, and 11 (25.5%) were widows.

Figure 2.

Antibody detection in saliva and serum of HIV positive study group Out of 100 subjects in the study group, 99 (99%) were tested positive for HIV antibodies in saliva and all the subjects were detected HIV positive in serum of HIV positive subjects, whereas all the subjects 100 (100%) were tested negative for HIV antibodies in serum and saliva of control group (P-value <0.05). ELISA kit was found to be 99% sensitive and 100% specific for detection of HIV antibody in saliva of the study group, whereas it was found 100% sensitive and specific for detection of antibodies in serum of study group (P-value <0.05)

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was done using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) version 17 statistical analysis software. The tests used for analysis were independent t-test and Pearson's correlation. On applying independent t-test on all saliva and serum samples, probability value (P-value) obtained was < 0.05 and the results were highly significant.

Discussion

Generation of specific antibody response is a critical component of the host defense against pathogenic microorganisms and HIV is no exception. The presence of virus-specific antibodies in mucosal secretions including saliva has been well documented. HIV specific antibodies of immunoglobulin isotopes IgA, IgG, and IgM are readily found in salivary secretions of infected people but at levels considerably lower than those in blood.[10] Detection of HIV-specific antibodies in oral fluid transudate has been exploited recently as a highly sensitive and specific alternative to blood for diagnosis and population surveillance. Spencer Hedge et al. in 1998 explained the diagnostic significance of antibodies in oral secretions. Immunoglobulins (IgG) were identified in human saliva nearly 50 years ago and shortly thereafter in 1963, the prevalence of IgA in saliva was demonstrated.[11] Parry et al., in 1987, performed sensitive assays for viral antibodies in saliva. They described methods for detecting antibodies to HIV as well as antibodies to other viruses and proposed saliva as an alternative specimen for epidemiological investigations.[12] ELISA has been modified by increasing the specimen volume, altering the incubation periods, reagent concentrations, and reducing the assay cutoff values for detection of HIV antibody in saliva.[6,7,13,14] These modifications have resulted in improved ELISA sensitivity and specificity in saliva compared with those of matched serum test as reported by Granade et al. in year 1995 and 1998.[5] In the present study, we have evaluated diagnostic usefulness of saliva for detection of HIV antibodies. Unlike venipuncture, saliva collection is painless, non-invasive, inexpensive, simple, and rapid. In our study, saliva and serum samples of 100 confirmed seropositive patients and 100 healthy individuals were tested by ELISA kit. The result was found to be 99% sensitive and 100% specific for saliva samples while it was 100% sensitive and specific for serum samples. The results were congruent with studies done by Soto-Ramirez et al.[15] in 1992, in 1993, Ishikawa et al. in 1995,[16] and recently by Pant Pai et al. in 2007.[17] Diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of saliva for detection of HIV antibodies is reported by various authors is given in Table 4. Thus, in the various studies, diagnostic sensitivity of saliva, analyzed by ELISA, is ranged from 95% to 100% and diagnostic specificity of under 90% has been reported.[8,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]

Table 4.

Sensitivity and specificity of saliva for the detection of HIV antibodies by various authors

| Authors | Year | HIV positive subjects | HIV negative subjects | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parry et al. (ELISA) | 1987 | 43 | 10 | 100 | 100 |

| Arichbald et al. (ELISA) | 1991 | 21 | --- | 95.2 | --- |

| Chamanput et al. (ELISA) | 1993 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 100 |

| Luo et al. (ELISA) | 1995 | 50 | 57 | 96 | 100 |

| Ishiwak et al. (ELISA) | 1995 | 63 | 76 | 100 | 100 |

| Pasquier et al. (ELISA) | 1997 | 530 | --- | 100 | 99.8 |

| Prudenico et al. (ELISA) | 1998 | 187 | 115 | 95.2 | 97.4 |

| Schramm et al. (ELISA) | 1999 | 684 | 652 | 100 | 99.1 |

| Wesolowski et al. (ELISA) | 2006 | 26066 | --- | 90 | 99.8 |

| Nitika et al. (STRIP Test) | 2007 | 146 | 304 | 100 | 100 |

| Balamane et al. (Viral RNA test ) | 2010 | 69 | --- | 95 | - |

| Joanne et al. (Viral RNA Test ) | 2017 | 8 | 8 | 87.5 | 95 |

| Chengting et al. (Agglutination PCR ADAP) | 2018 | 22 | 22 | 100 | 100 |

Conclusion

Saliva can be used as an alternative to serum and plasma for the detection of HIV antibodies as a highly sensitive and specific alternative to blood for diagnosis and population surveillance. Salivary fluid collection is painless, non-invasive, inexpensive, simple, and rapid. Salivary antibody testing may provide better access to epidemic outbreaks, children, large populations, hard-to-reach risk groups and may thus play a major role in the surveillance and control of highly infectious diseases. Still much more work is required in this field worldwide so that saliva can be used as alternative to blood for detection of HIV antibodies as saliva has very less concentration of HIV antibodies due to presence of enzyme SLPI (salivary leukocyte protease inhibitor) which does not allow the virus to increase its load in saliva as compared to blood; hence, due to decrease in viral load, we have to develop specialized ELISA kits with increased efficacy and accuracy for detection of HIV antibodies to avoid the false-positive results as HIV/AIDS is a life-threatening disease and highly infectious.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Piot P, Quinn TC. The AIDS pandemic – A global healthparadigm. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2210–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1201533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS data 2018. Available from: http://wwwunaidsorg .

- 3.Chinnapolamada JR, Chiranjeevi SA, Tupalli AR, Erugula SR. ‘Sialodiagnosing’ HIV infection: A dissected review. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2015;27:213–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenspan JS, Greenspan D. Oral Manifestations of HIV Infection. In: Campo J, Perea MA, Romero J, Cano J, Hernando V, Bascones A, editors. Oral Transmission of HIV, reality or fiction An update Oral Dis 1997. Vol. 12. Hong Kong: Quintessence Publishers; 2006. pp. 219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Granade TC, Phillips SK, Parekh B, Pau C, George JR. Oral fluids as a specimen for detection and confirmation of antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;5:395–9. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.4.395-399.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowdell M, Wainwright A, Barnes D. Comparison of a commercial 2nd generation assay with a 3rd generation test in the detection of anti HIV antibodies in saliva samples, abstr PO-B40-2449,p 543 In Ab-stracts of the IXth International Conference on AIDS, Berlin, Germany, 6 to 11 June1993 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freel SA, Williams JM, Nelson JA, Patton LL, Fiscus SA, Swanstrom R, et al. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in saliva and blood plasma by V3-specific heteroduplex tracking assay and genotype analyses. J Virol. 2001;75:4936–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.10.4936-4940.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts KJ, Grusky O, Swanson AN. Outcomes of blood and oral fluid rapid HIV testing: A literature review, 2000-2006. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:621–37. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamers RL, Smit PW, Stevens W, Schuurman R, Rinke de Wit TF. Dried fluid spots for HIV type-1 viral load and resistance genotyping: A systematic review. Antivir Ther. 2009;14:619–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reigadas S, Schrive MH, Aurillac-Lavignolle V, Fleury HJ. Quantitation of HIV-1 RNA in dried blood and plasma spots. J Virol Methods. 2009;161:177–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedges SR, Russel MW, Mestecky J. Diagnostic significance of antibodies in oral secretions. In: Specter, Steven, Bendinelli, Mauro, Friedman, Herman, et al., editors. Rapid Detection of Infectious Agents. New York: Plenuns Press; 1998. p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parry JV, Perry KR, Mortimer PP. Sensitive assays for viral antibodies in saliva: An alternative to tests on serum. Lancet. 1987;335:72–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92737-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klokke AH, Ocheng D, Kalluvya SE, Nicoll AG, Laukamm-Josten U, Parry JV, et al. Field evaluation of immunoglobulin G antibody capture tests for HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies in African serum, saliva and urine [letter] Aids. 1991;5:1391–2. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199111000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van den Akker R, van den Hoek JA, van den Akker WM, Kooy H, Vijge E, Roosendaal G, et al. Detection of HIV antibodies in saliva as a tool for epidemiological studies. Aids. 1992;6:953–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soto-Ramirez LE, Hernandez-Gomez L, Sifuentes-Osornio J, Barriga-Angulo G, Duarte de Lima D, Lopez-Portillo M, et al. Detection of specific antibodies in gingival crevicular transudate by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2780–3. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.11.2780-2783.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishikawa S, Hashida S, Hashinaka K, Hirota K, Saitoh A, Takamizawa A, et al. Diagnosis of HIV-1 infection with whole saliva by detection of antibody IgG to HIV-1 with ultrasensitive enzyme immunoassay using recombinant reverse transcriptase as antigen. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;10:41–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pant Pai N, Joshi R, Dogra S, Taksande B. Evaluation and diagnostic accuracy, feasibility and client preference for rapid oral fluid based diagnosis of HIV infection in rural India. PLoS One. 2007;2:e367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balamane M, Winters MA, Dalai SC, Freeman AH, Traves MW, Israelski DM, et al. Detection of HIV-1 in saliva: Implications for case-identification, clinical monitoring and surveillance for drug resistance. Open Virol J. 2010;4:88–93. doi: 10.2174/1874357901004010088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shugars DC, Slade GD, Patton LL, Fiscus SA. Oral and systemic factors associated with increased levels of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA in saliva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:432–40. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(00)70124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campo J, Perea MA, del Romero J, Cano J, Hernando V, Bascones A. Oral transmission of HIV, reality or fiction? An update. Oral Dis. 2006;12:219–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Granade TC, Phillips SK, Parekh B, Pau CP, George JR. Detection of antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in oral fluids: A large scale evaluation of immunoassay performance. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;2:171–5. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.2.171-175.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Archibald DW, Hebert CA. Salivary detection of HIV-1 antibodies using recombinant HIV-1 peptides. Viral Immunol. 1991;4:17–22. doi: 10.1089/vim.1991.4.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]