Abstract

An 86-year-old woman with Borrmann type III colorectal cancer (Union for International Cancer Control pT4aN2bM1c, pStage IVc) had received dexamethasone for the last 6 months as palliative care. She presented with a low-grade fever, chest pain and cough. Chest radiography on admission showed cavities and consolidations bilaterally in the upper lobes. A blood examination on admission revealed highly elevated serum β-d-glucan levels. The diagnosis by bronchoscopy was pulmonary nocardiosis. With trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and imipenem/cilastatin, the β-d-glucan levels were decreased, and chest X-ray showed improvement after 1 month. β-d-glucan is known to be a biomarker of fungal infection. It is possible that β-d-glucan levels also indicate a pulmonary infection by Nocardia.

Keywords: infections, pneumonia (infectious disease), pneumonia (respiratory medicine)

Background

Pulmonary nocardiosis is an unusual and severe opportunistic infection of the lungs caused by Nocardia spp.

It presents in immunocompromised patients with cavitary consolidation, including nodules, infiltration and reticular shadows.1 Due to its uncharacteristic clinical manifestation and varied radiologic findings, its clinical diagnosis is complicated. As a fungal marker, β-d-glucan represents a non-invasive surveillance and diagnostic tool for invasive fungal infections. Limited reports have described the association between Nocardia infection and β-d-glucan.2 3

Case presentation

An 86-year-old woman, treated for 6 months with dexamethasone (4 mg/day) as palliative care due to progressive colorectal cancer, was admitted to the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Izumi City General Hospital. The patient presented with a month of intermittent cough, low-grade fever and chest pain. She never smoked. Previous medical history was remarkable for 5 years of diabetes mellitus. In addition, she was performed distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer 4 years ago and received an excision of the breast cancers 15 years ago. When the patient was first seen, a physical examination indicated the following: body temperature, 37.5°C; heart rate, 72 beats/min; blood pressure, 146/72 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20/min and blood oxygen saturation level, 95% in room air. She was under low nutritional state with a body mass index of <20.

Investigations

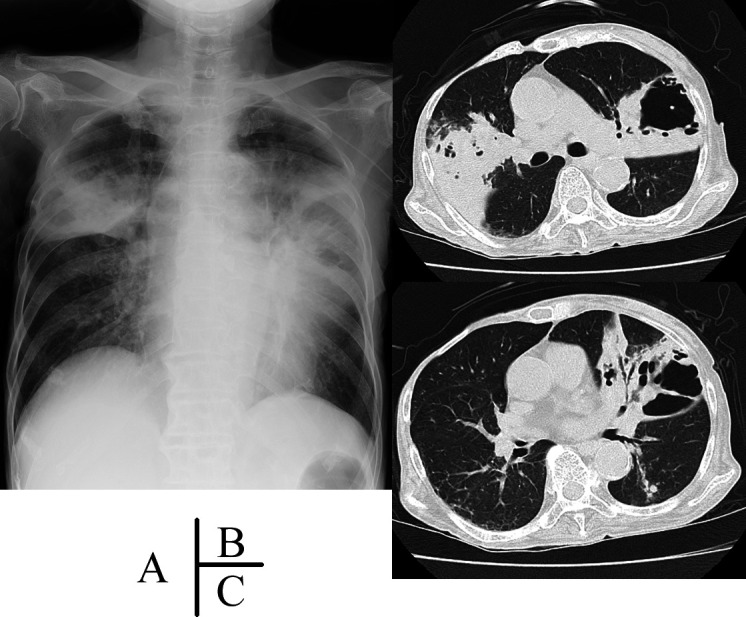

Chest radiography showed inhomogeneous shadows and large cavitary opacities in the bilateral upper fields (figure 1A). CT showed large tumour-like shadows with ground-glass opacity in the bilateral upper lobes and the presence of large cavitary lesions >5 cm in diameter with thin, irregular borders in the left upper lobe (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Chest radiography on the initial visit, showing consolidations and large cavitary opacities in the bilateral upper field. (B and C) Chest CT showing large tumour-like shadows with ground-glass opacity in the bilateral upper lobes and a large cavity with thin, irregular borders in the left upper lobe.

The patient’s laboratory tests had the following features: a white cell count of 9.5 ×109/L with 91.7% neutrophils, a haemoglobin level of 76 g/L and a C-reactive protein level of 14.8 mg/dL with no renal or liver function failure. The laboratory tests for HIV antibody, Aspergillus antigen, Aspergillus precipitating antibody, serum IgA antibody to glycopeptidolipid-core antigen and Mycobacterium-specific interferon-γ were negative. The tests for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. β-d-glucan level (reference value <20 pg/mL, Fungitec G test; Nissui Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) was elevated, reaching ≥300 pg/mL. We suspected opportunistic lung infections with bacteria, counting that she had been prescribed a high dose of methylprednisolone.

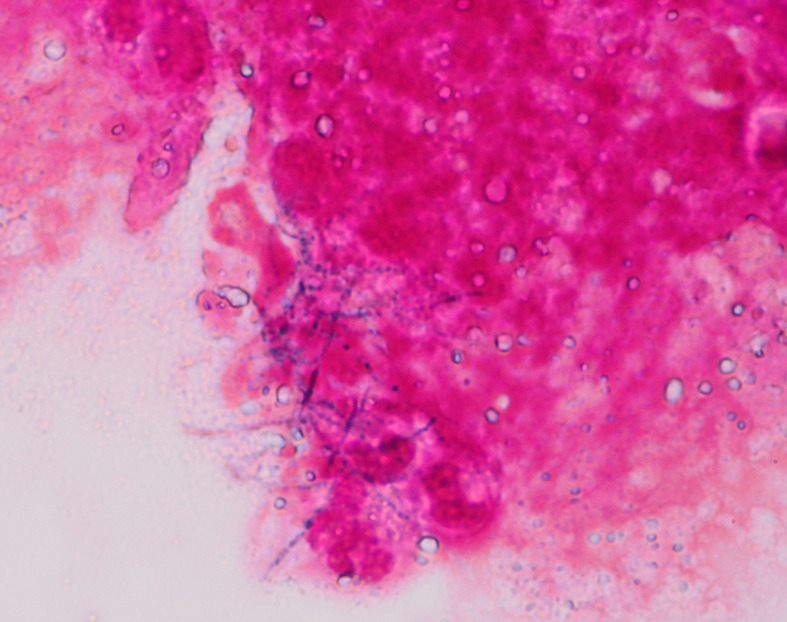

We considered invasive pulmonary aspergillosis to be the most likely cause of the high levels of β-d-glucan. However, her sputum of smear and culture was negative for Aspergillus. To make a diagnosis, bronchoscopy was performed from the right posterior and anterior bronchi. As performed the transbronchial biopsy from the right anterior and posterior segment, the pathological examination showed Gram-positive bacilli with microfilaments on Gram staining from the cavity wall tissue eaten by macrophages. There was the formation of fibrous granulomas with inflammatory cells composed neutrophils and lymphocytes in the alveolar cavity. We found no malignant findings. The smear of mucoid sputum obtained by brush cytology and bronchial washing revealed the similar Gram-positive bacilli (figure 2). Smear specimen findings compatible with Nocardia, was not confirmed from culture. From 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing, a Nocardia species, specifically Nocardia nova, was identified. The culture of this secretion detected methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, but not Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A sputum culture for Mycobacteria avium was positive only once during the hospitalisation period.

Figure 2.

Gram staining of the secretion from the cavity shows Gram-positive rods with branching microfilaments. Nocardia nova was identified by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing.

Differential diagnosis

Reported radiographic patterns for Nocardia infection include lobar or multilobar consolidation, infiltrative shadows, tumour shadows, cavities and bronchodilatational changes.1 In our case, radiological abnormalities presented large tumour-like shadows and large cavitary lesions. For the cavitary lesions, we need to differentiate infectious or non-infectious diseases. First, we consider non-infectious diseases. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is an autoimmune disease that causes vasculitis in the small vessels. GPA presents central cavitation in up to 50% of cases and is more common in nodules larger than 2 cm.4 Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative in the present case. Cavitary pulmonary cancer is most commonly (70%) caused by squamous cell carcinoma.5 6 In our case, the pathological examination revealed no malignant findings. Second, we think about infectious diseases. Differential diagnoses from fungal infection and acid-fast bacteria are often the most important point, based on patient’s immunologically deficient status. Nocardiosis is also often complicated by M. avium complex infection or chronic necrotising pulmonary aspergillosis.7 8 In the present case, the high level of β-d-glucan hampered differentiation from pulmonary aspergillosis. Our patient was infected with Nocardia, M. avium and S. aureus, but not with Aspergillus.

Treatment

We diagnosed with pulmonary nocardiosis. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX 1600 mg; 320 mg/day) and imipenem hydrate/cilastatin sodium (IPM/CS 1.5 g; 1.5 g/day) were prescribed as initial therapy. On the second day of the treatment, the patient suddenly developed an episode of tetanic convulsion. Brain MRI showed no abnormalities. The IPM/CS was considered the possible cause of seizures. The convulsive episode did not repeat after cessation of IPM/CS. Eighteen-day treatment with TMP/SMX alone improved cough, low-grade fever and chest pain. The inflammatory reaction, C-reactive protein, was normalised with white cell counts. Later, the patient was switched to oral minocycline (200 mg/day) monotherapy following an increase in the potassium serum levels as side effects of TMP/SMX.

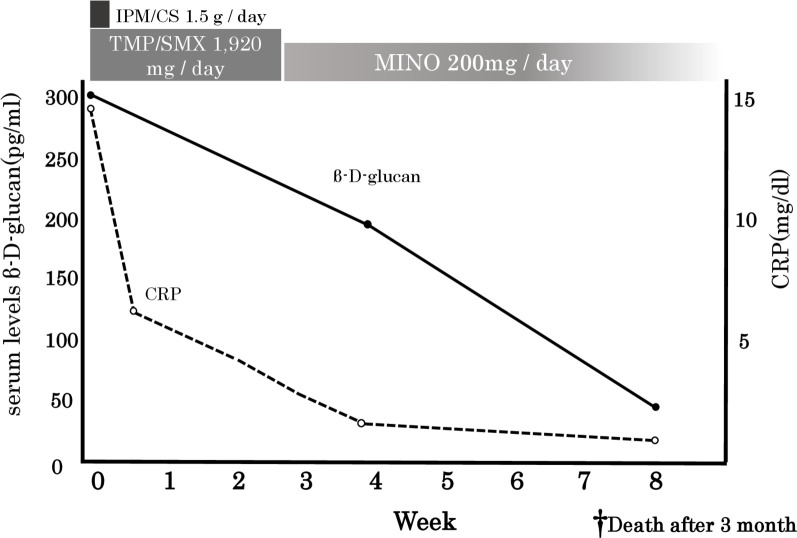

Chest radiography on the 28th day of treatment showed an improvement in the shadows (figure 3). Interestingly, the high levels of β-d-glucan observed at pretreatment decreased in parallel with the amelioration of the clinical features: the levels decreased from ≥300 pg/mL to 42.5 pg/mL after 45 days (figure 4). The present patient showed no history of eating large amounts of mushrooms, receiving β-lactam antibiotics or immunoglobulin/albumin preparations along with haemodialysis, which are common sources of false-positive test findings for high β-d-glucan levels.9 10

Figure 3.

Chest radiography on the 28th day post-treatment showing improved consolidation shadows and cavities. The straight line in the left lower zone indicates left-sided pneumothorax.

Figure 4.

Changes in the CRP and serum β-d-glucan levels. CRP, C-reactive protein; CS, cilastatin sodium; IPM, imipenem; SMX, sulfamethoxazole; TMP, trimethoprim.

Outcome and follow-up

The β-d-glucan levels decreased after the treatment, without antimycotic agents. We therefore believe that the increased β-d-glucan levels can be attributed to Nocardia. Unfortunately, the patient died from cancerous peritonitis 3 months after treatment initiation.

Discussion

Nocardia is a family of aerobic Gram-positive bacteria classified as actinomycetes, which are ubiquitous bacteria in the soil and aqueous environments. While actinomycetes are prokaryotes, like all bacteria, they are also micro-organisms with mycelium, and their infection patterns resemble those of fungi.11 Nocardiosis is mainly recognised as an opportunistic infection primarily affecting immunodeficient patients who undergo long-term treatments with steroid hormones and immunosuppressants or who have a weakened immune system, such as patients with progressive cancer or blood diseases.7 In the present case, the patient probably developed nocardiosis due to her immunosuppressive condition, which was linked to colorectal cancer itself and the use of steroid hormones for palliative therapy.

The most abundant fungal cell wall consists of the following: a glucose-linked polysaccharide called β-d-glucan, mannan and chitin on the outside. β-d-glucan is widely present in various pathogenical fungi such as Candida spp, Fusarium spp, Aspergillus spp and Pneumocystis spp, which was not observed in the cell wall of zygomycetes. These cell wall structures are fungi-specific.12 Therefore, the β-d-glucan levels are a useful marker for a fungal infection diagnosis and reflect the actual extent of fungal infection. The measurement of the β-d-glucan levels is based on a reaction with limulus reagent, which contains blood cell extract from horseshoe crab for G factor activation.13

Nocardia’s cell wall is type IV and mainly composed of arabinose, galactose, meso-2,6-diaminopimelic acid and mycolic acids.14 β-d-glucan is not believed to be present in the cell wall of any bacteria, including Nocardia spp.15 However, a recent study suggested that the polysaccharides found in the cell walls of Nocardia spp trigger the limulus reaction. Sawai et al reported high levels of serum β-d-glucan in patients with disseminated N. farcinica infection.2 Koncan et al found that the culture solutions of N. neocaledoniensis, N. abscessus and N. cyriacigeorgica showed positive results on the β-d-glucan assay.3 Additionally, refer to Yoneda’s description in the patent application publication (US8822163B2), if it is a polysaccharide comprising β-glucan as a constituent, it is likely that β-d-glucan levels elevate. Certain bacteria, such as Actinomyces, Nocardia, fungi and mushrooms containing natural polysaccharides in the cell wall, which may even contain β-glucan depending on the species.16 The elevated serum β-d-glucan level might be due to cross-reactivity.

Furthermore, Nocardia infection is often accompanied by other pathogens, which often show increased β-glucan levels. Aspergillus and Mycobacteria are the most common agents present in cases of mixed infection.7 8 Because of cavitary lesion involving elevation of serum β-d-glucan levels, we considered the possibility of an Aspergillus infection in the present case. We were unable to confirm a fungal infection from a respiratory sample. It is difficult to prove Aspergillus spp from the respiratory sample microbiologically.17 18 In this case, we treated pulmonary nocardiosis, concerned about the possibilities of Aspergillus infection without use of antifungal agent.

There have been previous reports of some antibiotics interacting with β-d-glucan.8 9 In the present case, the high levels of β-d-glucan were detected before treatment with the β-lactam antibiotic (IPM/CS) and TMP/SMX. No other antibiotic treatment was administered prior to the admission. In the vast majority of cases, nocardiosis develops in patients with a poor physical condition following who have an immunodeficient condition. Before the definitive diagnosis of nocardiosis, treatments which can lead to false positives, for example, TMP/SMX, antifungal agents or immunoglobulins/albumins are often administered.9 10

Patient’s perspective.

At the start of her disease course, my mother lost hope and was heartbroken because of her advanced colorectal cancer. She prepared herself for potential pain from the cancer and her eventual death. Therefore, we were surprised to receive the diagnosis of remediable pneumonia. While it was painful to place her under quarantine for a week to avoid mycobacterial infection, we were subsequently able to spend another 3 months with her until she passed away.

Learning points.

The differential diagnoses of radiological cavitary lesions should consider various infections or non-infectious diseases (eg, pulmonary tuberculosis, non-tuberculous mycobacteria, or fungi, vasculitis syndrome and primary and metastatic malignancies).

To recognise the risk of infectious disease development (eg, Candida spp, Fusarium spp, Aspergillus spp and Pneumocystis spp), β-d-glucan levels should be carefully observed.

Nocardia infections may elevate β-d-glucan levels.

Most false-positive reactions of β-d-glucan assays are attributed to the use of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, antifungal agents or immunoglobulin/albumin preparations haemodialysis.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Mr B Quinn (Japan Medical Communication) for carefully proofreading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: All persons certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content, including participation in the concept, design, analysis, writing, or revision of the manuscript. Furthermore, each author certifies that this material or similar material has not been and will not be submitted to or published in any other publication before its appearance in the Case Report in BMJ Case Reports. HM: planning of the manuscript; KY, HM, YN: conception and design of the manuscript; KY: conduct and reporting of the manuscript; KY, HM and YN: acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kanne JP, Yandow DR, Mohammed T-LH, et al. Ct findings of pulmonary nocardiosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011;197:W266–72. 10.2214/AJR.10.6208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sawai T, Nakao T, Yamaguchi S, et al. Detection of high serum levels of β-D-glucan in disseminated nocardial infection: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 2017;17:272. 10.1186/s12879-017-2370-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koncan R, Favuzzi V, Ligozzi M, et al. Cross-reactivity of Nocardia spp. in the fungal (1-3)-β-d-glucan assay performed on cerebral spinal fluid. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2015;81:94–5. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cordier JF, Valeyre D, Guillevin L, et al. Pulmonary Wegener's granulomatosis. A clinical and imaging study of 77 cases. Chest 1990;97:906–12. 10.1378/chest.97.4.906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seo JB, Im JG, Goo JM, et al. Atypical pulmonary metastases: spectrum of radiologic findings. Radiographics 2001;21:403–17. 10.1148/radiographics.21.2.g01mr17403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhuri MR. Cavitary pulmonary metastases. Thorax 1970;25:375–81. 10.1136/thx.25.3.375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurahara Y, Tachibana K, Tsuyuguchi K, et al. Pulmonary nocardiosis: a clinical analysis of 59 cases. Respir Investig 2014;52:160–6. 10.1016/j.resinv.2013.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hui CH, Au VWK, Rowland K, et al. Pulmonary nocardiosis re-visited: experience of 35 patients at diagnosis. Respir Med 2003;97:709–17. 10.1053/rmed.2003.1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mennink-Kersten MASH, Warris A, Verweij PE. 1,3-Beta-D-Glucan in patients receiving intravenous amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2834–5. 10.1056/NEJMc053340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marty FM, Lowry CM, Lempitski SJ, et al. Reactivity of (1-->3)-beta-d-glucan assay with commonly used intravenous antimicrobials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006;50:3450–3. 10.1128/AAC.00658-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson JW. Nocardiosis: updates and clinical overview. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:403–7. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeković DB, Kwiatkowski S, Vrvić MM, et al. Natural and modified (1-->3)-beta-D-glucans in health promotion and disease alleviation. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2005;25:205–30. 10.1080/07388550500376166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obayashi T, Yoshida M, Mori T, et al. Plasma (1-->3)-beta-D-glucan measurement in diagnosis of invasive deep mycosis and fungal febrile episodes. Lancet 1995;345:17–20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91152-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown-Elliott BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006;19:259–82. 10.1128/CMR.19.2.259-282.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellis M. Infectious diseases of the respiratory tract. 213 1st edn Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoneda A. Method for measuring beta-glucan, and beta-glucan-binding protein for use in the method. Patent application publication US8822163B2 2014;10. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skov M, McKay K, Koch C, et al. Prevalence of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis in an area with a high frequency of atopy. Respir Med 2005;99:887–93. 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitasato Y, Tao Y, Hoshino T, et al. Comparison of Aspergillus galactomannan antigen testing with a new cut-off index and Aspergillus precipitating antibody testing for the diagnosis of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Respirology 2009;14:701–8. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01548.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]