Abstract

The most dynamic period of postnatal brain development occurs during adolescence, the period between childhood and adulthood. Neuroimaging studies have observed morphologic and functional changes during adolescence, and it is believed that these changes serve to improve the functions of circuits that underlie decision-making. Direct evidence in support of this hypothesis, however, has been limited because most preclinical decision-making paradigms are not readily translated to humans. Here, we developed a reversal-learning protocol for the rapid assessment of adaptive choice behavior in dynamic environments in rats as young as postnatal day 30. A computational framework was used to elucidate the reinforcement-learning mechanisms that change in adolescence and into adulthood. Using a cross-sectional and longitudinal design, we provide the first evidence that value-based choice behavior in a reversal-learning task improves during adolescence in male and female Long–Evans rats and demonstrate that the increase in reversal performance is due to alterations in value updating for positive outcomes. Furthermore, we report that reversal-learning trajectories in adolescence reliably predicted reversal performance in adulthood. This novel behavioral protocol provides a unique platform for conducting biological and systems-level analyses of the neurodevelopmental mechanisms of decision-making.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT The neurodevelopmental adaptations that occur during adolescence are hypothesized to underlie age-related improvements in decision-making, but evidence to support this hypothesis has been limited. Here, we describe a novel behavioral protocol for rapidly assessing adaptive choice behavior in adolescent rats with a reversal-learning paradigm. Using a computational approach, we demonstrate that age-related changes in reversal-learning performance in male and female Long–Evans rats are linked to specific reinforcement-learning mechanisms and are predictive of reversal-learning performance in adulthood. Our behavioral protocol provides a unique platform for elucidating key components of adolescent brain function.

Keywords: computational psychiatry, meta-learning, neurodevelopment, reversal learning, reward

Introduction

Adolescence is the period of development between childhood and adulthood during which individuals experience increased demands on self-guided decision-making compared with those experienced during childhood (Blakemore and Robbins, 2012). Many of these decisions occur under risky or ambiguous situations and can be associated with severe negative outcomes, such as illicit substance use, engaging in risky sexual behaviors, and reckless driving (Chambers et al., 2003; Kann et al., 2016). Empirical studies have reported that adolescents perform worse compared with adults in laboratory tasks of decision-making (Gardner and Steinberg, 2005; van der Schaaf et al., 2011; Christakou et al., 2013; Barkley-Levenson and Galván, 2014; Decker et al., 2016; Anandakumar et al., 2018), but the mechanisms underlying theses age-related changes in behavior are not known.

Decisions are guided by action values generated in the brain through multiple computational steps based on previous actions and outcomes (Sutton and Barto, 1998; Dayan and Daw, 2008; Niv, 2009; Lee, 2013). Reinforcement-learning algorithms have been used to quantify the degree to which specific computational steps influence choice, and there is considerable interest in the use of these models for advancing our understanding of the developmental mechanisms underlying decision-making (Hartley and Somerville, 2015; Nussenbaum and Hartley, 2019). Recent studies have found that when compared with adults, adolescents show a stronger tendency to learn more from rewards than punishment (Palminteri et al., 2016), and also have lower learning rates (Van Den Bos et al., 2012; Davidow et al., 2016), altered prediction error encoding (Hauser et al., 2015), and increased exploratory behaviors (Christakou et al., 2013). Age-related changes in these reinforcement-learning processes may explain, in part, why adolescence is a period associated with risky behavior and poor decision-making.

Identifying the precise mechanisms underlying age-related changes in decision-making could provide critical insightsinto neurodevelopmental mechanisms mediating mental illness (Chambers et al., 2003; Schneider, 2013; Hartley and Somerville, 2015; Simon and Moghaddam, 2015). Decision-making is impaired in individuals with a range of mental disorders (Ersche et al., 2008; McKirdy et al., 2009; Ghahremani et al., 2011; Schlagenhauf et al., 2014; Reddy et al., 2016), and symptoms of mental illness emerge during adolescence (Kessler et al., 2007; Paus et al., 2008). Nevertheless, elucidating the biological correlates of decision-making during adolescence presents a major challenge as this developmental period is extremely short in rodents (Schneider, 2013) and most translationally analogous decision-making tasks require rats to be trained for several weeks (Mitchell et al., 2014; Groman et al., 2018). Moreover, decision-making tasks that work well in adults often do not work well in juveniles and thus limit the ability to collect repeated assessments throughout the life span of a subject. Therefore, linking rapid neurodevelopmental and behavioral changes has been difficult.

The goal of the current study was to rapidly assess adaptive choice behavior using a novel reversal-learning task at distinct adolescent time points and into adulthood in rats. Using both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs, we trained rats to acquire and reverse in a three-choice reversal-learning paradigm (Groman et al., 2018) at four distinct adolescent ages [postnatal day 30 (P30), P50, P70, and P90]. We also examined whether improvements in reversal-learning performance during adolescence predicted performance of the same rats in adulthood (P130, P150, and P170). The cross-sectional and longitudinal studies in rats presented here used a computational approach to identify the precise reinforcement-learning mechanisms underlying these age-related improvements in reversal-learning performance.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male (M) and female (F) Long–Evans rats (N = 60; 31 M/29 F) were bred in-house using 10 breeding pairs. Rats were weaned at P21 and housed in standard laboratory cages on a 12 h light/dark cycle in a vivarium (lights on at 7:00 A.M.). Animals had ad libitum access to water and food until behavioral testing began. All experimental procedures were performed as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Yale University and according to National Institutes of Health and institutional guidelines and the Public Health Service Policy on the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

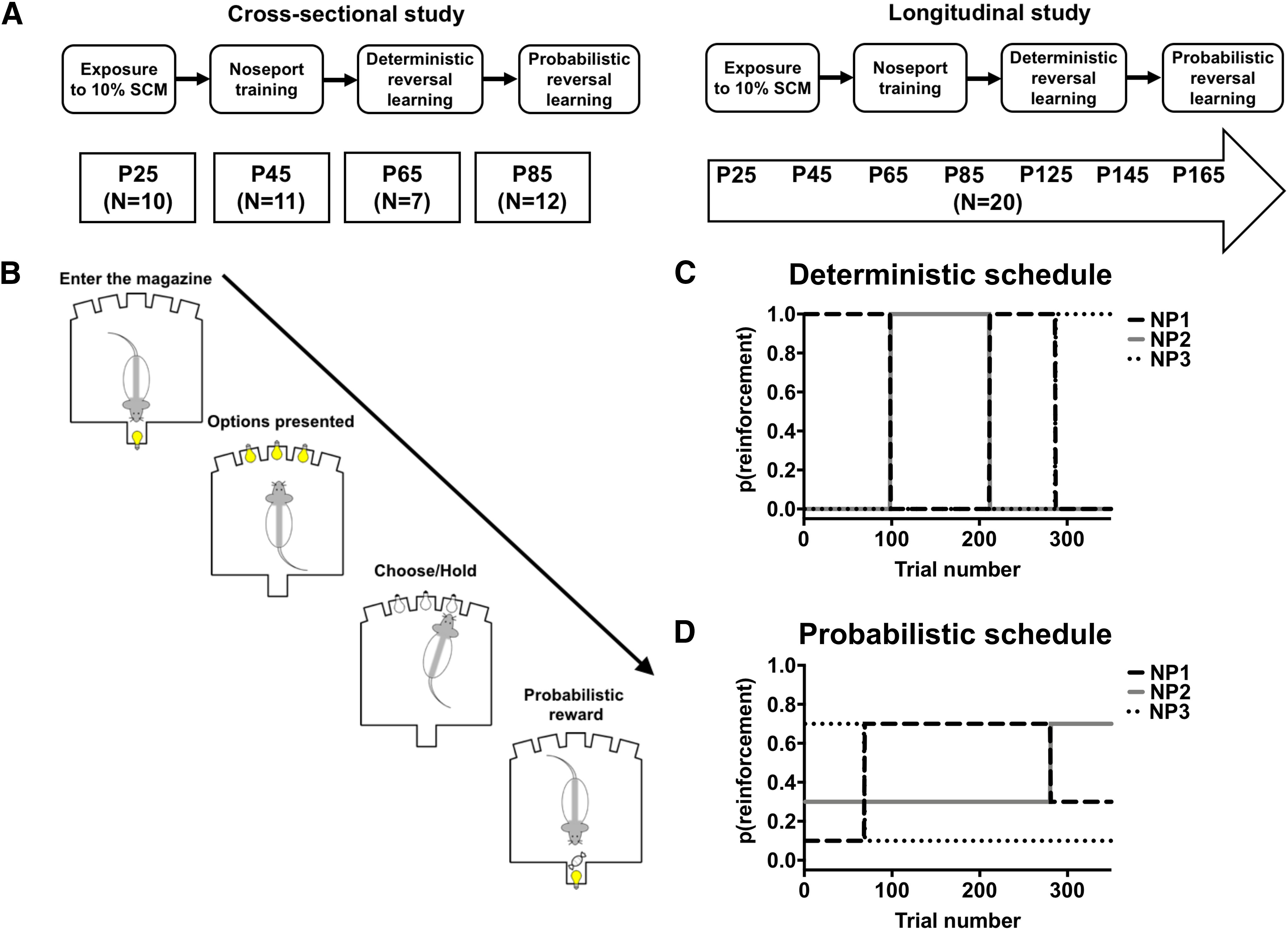

Rats were assigned to participate in either a cross-sectional study (N = 40; 21 M/19 F; Fig. 1A, left) or a longitudinal study (N = 20; 10 M/10 F; Fig. 1A, right). Animals at different ages in the cross-sectional study underwent a single round of testing on the reversal-learning task (described below). In contrast, animals in the longitudinal study were repeatedly tested at different ages on the reversal-learning task. This combination of studies enabled us to determine whether reversal-learning performance changed with age and/or experience, and to quantify trajectories of reversal-learning performance during adolescence. The transition age from childhood, adolescence, and adulthood in the rat are not well defined (Schneider, 2013; Sengupta, 2013), so we assessed reversal-learning performance at different ages that spanned the entire developmental period (cross-sectional and longitudinal studies: P30, P50, P70, and P90) and into adulthood (longitudinal study: P130, P150, and P170).

Figure 1.

Assessing adaptive choice behavior in the reversal-learning task throughout adolescence in the rat. A, Left, Experimental design used in the cross-sectional study. Separate cohorts of rats began testing at P25, P45, P65, or P85. A, Right, Experimental design used in the longitudinal study. B, Schematic of a single trial in the reversal-learning task. C, The deterministic schedule of reinforcement for each of the three noseport (NP) options. D, The probabilistic schedule of reinforcement for each of the three noseport options.

Apparatus

All behavioral testing was performed in standard aluminum and Plexiglas operant conditioning chambers. These chambers were equipped with a photocell pellet-delivery magazine and a curved panel with five photocell-equipped noseports (NPs) on the opposite side (Med Associates). Chambers were housed inside of sound-attenuating cubicles, with background white noise being broadcast.

Operant training

Cross-sectional study.

Rats in the cross-sectional study were exposed to 10% sweetened condensed milk (SCM; % v/v, water) at P25, P45, P65, or P85 in a single 2 h session within their home cage. The following day, food was removed 12 h before rats were trained to make an operant response to receive a reward (60 μl of 10% SCM solution) in 12 h overnight sessions. Rats initiated trials by making a response into an illuminated magazine. A single noseport aperture located on the opposite panel was illuminated, and responses into the illuminated noseport resulted in the delivery of reward into the magazine. Sessions terminated when rats had earned 151 rewards or 720 min (e.g., 12 h) had elapsed, whichever occurred first. This reward criterion, rather than a trial criterion, was used to minimize differences in satiation set points that likely exist between adolescent and adult rats. If rats did not obtain 151 rewards in a single, overnight session, the operant training session was repeated the following day(s) until the performance criterion was met.

Longitudinal study.

Rats included in the longitudinal study were exposed to 10% sweetened condensed milk at P25 in a single 2 h session within their home cage. The following day, food was removed 12 h before rats were trained to make an operant response to receive a reward (60 μl of 10% SCM solution) in 12 h overnight sessions. Rats initiated trials by making a response into an illuminated magazine. A single noseport aperture located on the opposite panel was illuminated, and responses into the illuminated noseport resulted in the delivery of reward into the magazine. Sessions terminated when rats had earned 151 rewards or 720 min had elapsed, whichever occurred first. If rats did not obtain 151 rewards in a single, overnight session, the operant training session was repeated in the following days until the performance criterion was met. There were technical difficulties during the first operant training session: a subset of rats removed a barrier that was placed between the grid floor and operant wall, and climbed underneath the wire grid floors at some point during the session. The number of operant sessions that rats required to reach criterion, therefore, was slightly greater in the longitudinal study compared with that in the cross-sectional study (see Results).

Deterministic and probabilistic reversal learning.

Once operant responding had been established, the ability of rats to acquire and reverse deterministically reinforced three-choice spatial discrimination problems was assessed in three consecutive overnight sessions (Fig. 1B). A response into the magazine resulted in the illumination of three noseport apertures, and rats could respond to any of the illuminated noseports to earn a deterministically delivered reward (Fig. 1C). One noseport was randomly assigned to deliver reward, while the other two were assigned to not deliver reward by a computer program at the start of each session. When rats met a performance criterion (21 choices on the highest reinforced noseport in the last 30 trials), the assignments reversed: the reinforced noseport (100%) was now assigned to not deliver reward (0%), while one of the unreinforced noseports was now assigned to deliver reward (100%). These reinforcement probabilities remained unchanged until the performance criterion was once again met, after which the reinforcement probabilities reversed again between the reinforced noseport and one of the unreinforced noseports. Each time the performance criterion was met, these assignments reversed. The occurrence of a reversal was, therefore, contingent on the performance of the rat. Sessions terminated when rats earned 151 rewards or 720 min had elapsed. Rats completed three sessions using this deterministic schedule of reinforcement. If rats failed to earn 151 rewards in a single session, that session was repeated the following day.

The ability of rats to acquire and reverse probabilistically reinforced three-choice spatial discrimination problems was then assessed in three consecutive overnight sessions. Each noseport aperture was randomly assigned to deliver reward with a probability of 70%, 30%, or 10% by the program at the start of each session (Fig. 1D). When rats met a performance criterion (21 choices on the highest reinforced noseport in the last 30 trials), the probabilities reversed: the most frequently reinforced noseport (70%) was now assigned to deliver reward with a lower probability (e.g., 30% or 10%), and one of the less frequently reinforced noseports (30% or 10%) was now assigned to deliver reward with the highest probability (70%). Sessions terminated when rats received 151 rewards or 720 min had elapsed, whichever occurred first. If rats failed to earn 151 rewards in a single session, that session was repeated.

Once rats completed the third session under the probabilistic schedule of reinforcement, rats in the cross-sectional study were killed and tissue was collected for future postmortem analyses (not reported here). Rats in the longitudinal study were returned to the vivarium and given ad libitum access to food. They remained undisturbed until they had reached the next testing age (e.g., P50, P70, P90, P130, P150, and P170).

Data analyses

Logistic regression.

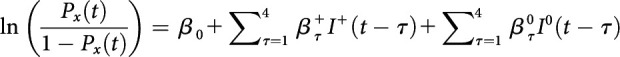

Age-related changes in outcome-based learning could be due to variation in how rats use rewarded and unrewarded outcomes to guide their choices. To test this rigorously, the choice behavior of rats was analyzed by fitting the following logistic regression model that estimated the likelihood of repeating the same choice as in each of the four previous trials according to whether the previous trial was rewarded or not, as follows:

|

where Px(t) denotes the probability that in trial t the rat would make the same noseport choice, x, that could have been made in each of the last four trials (τ = 1–4). and indicate whether the choice of the target x in trial t by the rat was rewarded or not according to the following convention: = 1 if the choice of x in trial t was rewarded, 0 if the choice in trial t was unrewarded, and −1 if the animal chose the target other than x in trial t and was rewarded; = 1 if the choice of x in trial t was unrewarded, 0 if the choice in trial t was rewarded, and −1 if the animal chose the target other than x in trial t and was rewarded. For example, if the choices of the animal in the last four trials and their outcomes were NP1 rewarded (t-1), NP2 unrewarded (t-2), NP3 rewarded (t-3), and NP2 rewarded (t-4), then the values of the regressors included in the above logistic regression model for NP1 would be = 1, 0, −1, −1, and = 0, −1, 0, 0, for τ = 1, 2, 3, 4, respectively. Three separate logistic regressions were performed for each of the three noseport choices, and all of the regression coefficients for each of the three choices averaged separately for regressors corresponding to rewarded and unrewarded choices. Positive coefficients for the rewarded and unrewarded predictors indicate that rats are more likely to persist with the same choice, whereas negative regression coefficients indicate that rats are more likely to switch their choice.

Reinforcement-learning model.

Reinforcement-learning models predict that choices are based on outcomes from different actions that incrementally accrue over many trials. To investigate age-related changes in specific reinforcement-learning processes, choice data were fit with a forgetting reinforcement-learning model (Barraclough et al., 2004; Ito and Doya, 2009; Groman et al., 2016, 2018). This model was fit using 100 different initial parameter values with starting action values Qx(1) = 0 for all actions (x = NP1, NP2, NP3). The value updating for this model is as follows:

where the decay rate γ determines how quickly the action value decays and Δ(t) indicates the change in the action value depending on the outcome in trial t. If the outcome of the trial was rewarded, then the value function of the chosen port was updated by Δ(t) = Δ+, the reinforcing strength of reward. If the outcome of the trial was not rewarded, then the value function of the chosen port was updated by Δ(t) = Δ0, the aversive strength of no reward. Choice probability was calculated according to a softmax function and trial-by-trial choice data fit with these three parameters (e.g., γ, Δ+, and Δ0) selected to maximize the likelihood of the sequence of choices of each rat using the fminsearch function in MATLAB (version 2018a).

We also compared the fit of the forgetting reinforcement-learning model to the following three other reinforcement-learning models: (1) the same reinforcement-learning model described above but with the exclusion of the Δ0 parameter as this parameter did not change during adolescence; (2) a Q-learning algorithm that contained a single learning rate parameter (α) and the inverse temperature parameter (β; Ito and Doya, 2009); and (3) a Q-learning algorithm that contained two learning parameters—one for positive outcomes (α_g) and one for negative outcomes (α_l)—and the β value (Frank et al., 2004). The value updating for these models are as follows:

Differential forgetting without the Δ0 parameter:

Q-learning with a single learning rate:

Q-learning with two learning rates:

The Bayesian information criterion (BIC) for each model was calculated, and the BIC for each model summed across rats (see Table 2 and Table 3 for these results) The BIC for the forgetting reinforcement-learning model was lower compared with all other models, indicating that this model best fit the rat choice data.

Table 2.

Comparison of reinforcement-learning model fits for choice behavior under the deterministic schedule of reinforcement

| Age | Forgetting reinforcement learning model | Forgetting reinforcement learning without the Δ0 parameter | Q-learning model with one learning rate | Q-learning model with two learning rates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional | P30 | 18,363 | 19,703 | 20,098 | 19,842 |

| P50 | 20,429 | 21,186 | 21,430 | 20,638 | |

| P70 | 11,688 | 12,365 | 12,556 | 12,330 | |

| P90 | 21,504 | 22,611 | 23,351 | 23,238 | |

| Longitudinal | P30 | 41,666 | 43,910 | 45,432 | 44,975 |

| P50 | 39,581 | 42,054 | 44,154 | 43,638 | |

| P70 | 31,121 | 32,380 | 34,288 | 33,868 | |

| P90 | 29,678 | 30,572 | 32,925 | 32,782 | |

| P130 | 28,776 | 29,646 | 32,037 | 31,764 | |

| P150 | 23,109 | 23,285 | 25,224 | 24,938 | |

| P170 | 23,575 | 23,814 | 26,244 | 25,878 |

Values presented are the sum of the BIC. Bold values are those with the lowest BIC.

Table 3.

Comparison of reinforcement-learning model fits for choice behavior under the probabilistic schedule of reinforcement

| Age | Forgetting reinforcement learning model | Forgetting reinforcement learning without the Δ0 parameter | Q learning model with one learning rate | Q learning model with two learning rates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional | P30 | 17,056 | 17,490 | 18,429 | 17,779 |

| P50 | 20,197 | 21,469 | 23,334 | 21,667 | |

| P70 | 12,698 | 13,143 | 15,002 | 13,618 | |

| P90 | 23,629 | 24,226 | 26,378 | 25,083 | |

| Longitudinal | P30 | 40,206 | 41,340 | 45,013 | 42,970 |

| P50 | 44,004 | 45,458 | 49,861 | 47,510 | |

| P70 | 39,248 | 40,262 | 43,978 | 43,612 | |

| P90 | 37,043 | 37,690 | 41,346 | 40,660 | |

| P130 | 34,511 | 34,840 | 37,841 | 37,375 | |

| P150 | 33,139 | 33,276 | 36,046 | 35,992 | |

| P170 | 33,320 | 33,313 | 35,829 | 35,745 |

Values presented are the sum of the BIC. Bold values are those with the lowest BIC.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. All analyses were conducted in SPSS (version 26; IBM) using generalized linear models (GLMs) or generalized estimating equations (GEEs). GEE is a population-level approach based on the quasi-likelihood function that provides a population average estimate of parameters. GEEs permit the specification of a working correlation matrix to account for the within-subject correlation of responses on dependent variables of different distributions, including normal, binomial, and Poisson, that yields unbiased regression parameters relative to ordinary least-squares regression (Ballinger, 2004). Data were entered into a GEE model as repeated measures using a probability distribution based on the known properties of these data. The working correlation matrix for each model was determined by comparing the quasi-likelihood criterion (Pan, 2001). Factors in the model included sex (male/female) and age. Statistical significance of explanatory factors included in the model was assessed with the Wald χ2 test. Regression and multiple linear regression models were used to examine relationships between dependent variables. A nested regression model was used for regression analyses involving repeated measures. Principal component analyses (PCAs), a linear dimension reduction approach, was used to identify shared features among the dependent variables. To determine how reversal-learning trajectories during adolescence may be related to reversal-learning performance in adulthood, the slope between the dependent variables (e.g., the number of reversals completed and the reinforcement-learning parameter estimates) and adolescent age was calculated.

Results

Operant training

The number of operant training sessions that rats required to reach the reward criterion was first examined in the cross-sectional study. The number of sessions required to achieve the reward criterion increased across the ages examined, as follows: rats that began the operant training on P25, P45, P65, or P85 required 1.2 ± 0.13, 2.18 ± 0.38, 3.3 ± 0.78, or 4.42 ± 0.91 sessions, respectively, to reach the criterion. This is likely due to differences in body weight and, consequently, motivation that emerged across these ages. Rats at P90 were significantly larger than those at P30 (P90, 440 g; P30, 58 g; Table 1), so it is likely that P90 rats required additional days of mild food restriction to achieve the level of motivation that was observed in P30 rats following a single, mild food restriction. Nevertheless, all rats were able to acquire the operant response. Noseport responses were reinforced with the same amount of reward across the different ages. It is possible that younger rats could have been satiated by fewer rewards than older rats and, therefore, took longer to achieve the 151 reward criterion. We did not, however, observe age-related changes in session duration (χ2 = 0.16; p = 0.69), suggesting that rats at different ages were equally motivated by the reinforcer. Rats that were part of the longitudinal study and began training at P25 required 2.2 ± 0.25 sessions to achieve the reward criterion in a single session. Because of the technical difficulties experienced in the first operant training session in the longitudinal study (described above, Materials and Methods), the number of operant training sessions in the longitudinal study was greater than that required in the cross-sectional study.

Table 1.

Performance measures of rats in the reversal-learning task under deterministic and probabilistic schedules of reinforcement

| Study | Age | Weight (g) | Deterministic schedule |

Probabilistic schedule |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of sessions | Total trials completed | Session duration (h) | Total number of sessions | Total trials completed | Session duration (h) | |||

| Cross-sectional | P30 | 58 ± 2.4 | 3.0 ± 0.00 | 966 ± 71 | 6.56 ± 0.98 | 3.00 ± 0.00 | 1102 ± 32 | 7.69 ± 1.11 |

| P50 | 221 ± 9.3 | 3.18 ± 0.18 | 950 ± 68 | 8.58 ± 1.09 | 3.00 ± 0.00 | 1052 ± 61 | 6.42 ± 1.30 | |

| P70 | 357 ± 29 | 5.29 ± 0.78 | 1232 ± 127 | 8.56 ± 1.29 | 3.00 ± 0.00 | 1062 ± 73 | 6.21 ± 1.68 | |

| P90 | 433 ± 31 | 5.50 ± 0.79 | 1268 ± 133 | 7.66 ± 1.14 | 3.08 ± 0.08 | 1116 ± 35 | 5.61 ± 0.97 | |

| Longitudinal | P30 | 55 ± 4.1 | 3.75 ± 0.40 | 1299 ± 73 | 6.40 ± 0.66 | 3.55 ± 0.25 | 1197 ± 47 | 5.49 ± 0.65 |

| P50 | 153 ± 17 | 3.10 ± 0.07 | 1125 ± 36 | 4.13 ± 0.56 | 3.30 ± 0.18 | 1247 ± 44 | 3.73 ± 0.53 | |

| P70 | N/A | 3.65 ± 0.20 | 1136 ± 51 | 5.24 ± 0.66 | 3.20 ± 0.12 | 1147 ± 32 | 4.19 ± 0.60 | |

| P90 | N/A | 3.75 ± 0.51 | 968 ± 50 | 4.31 ± 0.62 | 3.35 ± 0.25 | 1122 ± 51 | 4.96 ± 0.69 | |

Total number of sessions is the total number of sessions rats required to reach the reward criterion. Total trials completed is the total number of trials rats completed under each schedule. Session duration is the average number of hours rats needed to reach the performance criterion. Values presented are mean ± SEM. N/A, Not applicable.

Reversal learning under the deterministic schedule of reinforcement

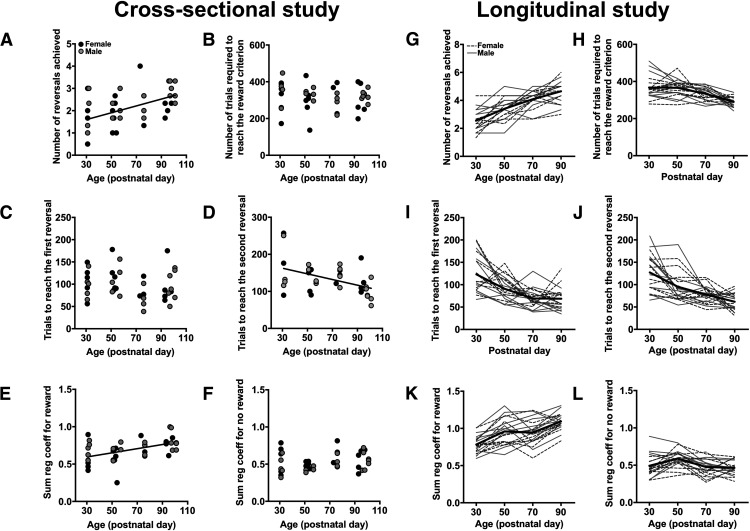

The performance of rats under the deterministic schedule of reinforcement was then examined (Table 1, general performance measures). The relationship between age and sex, and the dependent measures collected in the cross-sectional study, were examined with GLMs. Age, but not sex or the age × sex interaction, explained a significant amount of variance in the number of reversals rats were able to complete in the reversal-learning task (χ2 = 19.93; p < 0.001; φ = 0.71), as follows: as age increased across rats, the number of reversals that rats were able to complete in a single session increased (β = 0.018; 95% CI, 0.007–0.028; χ2 = 8.72; p = 0.003; Fig. 2A). This is not due to differences in the number of trials that rats completed across these ages (age: χ2 = 1.41; p = 0.24; φ = 0.19; Fig. 2B) as age still explained a significant amount of variance in the number of reversals rats performed when the number of trials completed was included in the model (age: χ2 = 7.42; p = 0.006; φ = 0.43). Moreover, the age-related increase in the number of reversals that rats were able to complete was not due to differences in the ability of rats to acquire the initial discrimination, as the number of trials required to achieve the first reversal did not vary as a function of age (age: χ2 = 0.10; p = 0.75; φ = 0.05; Fig. 2C). The number of trials rats required to reach the criterion following the change in reinforcement probabilities, however, was significantly explained by age (age: χ2 = 9.07; p = 0.003; φ = 0.48): as age increased across rats, the number of trials required to reach the performance criterion decreased (β = −0.76; 95% CI, −1.262 to −0.267; p = 0.003; Fig. 2D). These results indicate that the ability to adjust their choices in response to changes in the reinforcement contingencies improved across adolescent development.

Figure 2.

A–L, Performance in the deterministic reversal-learning task in the cross-sectional study (A–F) and the longitudinal study (G–L). A, The relationship between age and the average number of reversal rats completed in a single reversal-learning session. B, The relationship between age and the average number of trials required to achieve the reward criterion in a single session. C, The relationship between age and the number of trials rats required to reach the first reversal (i.e., acquire the initial discrimination). D, The relationship between age and the number of trials rats required to reach the second reversal. E, The relationship between age and the sum of the regression coefficients for the “rewarded” predictor in the logistic regression model. F, The relationship between age and the sum of the regression coefficients for the “unrewarded” predictor in the logistic regression model. G, The average number of reversals each rat completed in a single session at each of the four postnatal timepoints. H, The average number of trials required to achieve the reward criterion in a single reversal-learning session at each of the four postnatal timepoints. I, The number of trials rats required to reach the first reversal at each of the four postnatal timepoints. J, The number of trials required to reach the second reversal at each of the four postnatal timepoints. K, The sum of the regression coefficients for the rewarded predictor in the logistic regression model at each of the four postnatal timepoints. L, The sum of the regression coefficients for the unrewarded predictor in the logistic regression model at each of the four postnatal timepoints. Black circles, Female; gray circles, male; dotted black lines, female; solid gray lines, male; solid black line, average across sexes.

These age-related improvements in reversal performance may be due to changes in the ability of rats to use positive and/or negative outcomes to guide their subsequent choice. To examine this, the regression coefficients obtained with the logistic regression were compared between the ages. Similar to our previous studies (Groman et al., 2018, 2020), rats had an overall tendency to repeat their previous choices (e.g., regression coefficients were >0), but the likelihood of repeating an unrewarded choice was significantly lower than the likelihood that rats would repeat a rewarded choice (Fig. 2E,F). The three-way and two-way interactions between age, sex × trial lag were not significant factors for the likelihood of rats staying with a rewarded choice (χ2 < 1.93; p > 0.58), but the main effect of age was significant (χ2 = 4.68; p = 0.03; φ = 0.34): as age increased across rats, the likelihood of repeating a recently rewarded action increased (β = 0.0004; 95% CI, −0.0009 to 0.0018; χ2 = 5.50; p = 0.02; Fig. 2E). Age, however, did not explain a significant amount of variance in the likelihood of rats staying with an unrewarded choice (χ2 = 1.31; p = 0.25; φ = 0.18; Fig. 2F). Thus, the age-related improvements in reversal performance were due, specifically, to greater value updating after positive outcomes.

We then examined how performance in the deterministic reversal-learning task changed across adolescence when repeatedly assessed in the same rats (Table 1). Similar to the results of the cross-sectional study, sex and the age × sex interaction did not explain a significant amount of variance in the average number of reversals that rats completed in a single session (χ2 < 0.85; p > 0.35), but age did (χ2 = 98.37; p < 0.001; φ = 2.22): the number of reversals that rats completed in a single session increased across adolescence (β = 0.03; 95% CI, 0.027–0.040; χ2 = 93.30; p < 0.001; Fig. 2G). As the number of reversals that rats completed increased with age, the number of trials that rats required to reach the reward criterion decreased with age (age: χ2 = 54.32; p < 0.001; φ = 1.65; Fig. 2H). When the number of trials completed was included in the model, the effect of age still remained a significant factor in explaining the number of reversals rats performed (age: χ2 = 88.82; p < 0.001; φ = 2.11). Unlike the cross-sectional study, the number of trials required to achieve the first reversal decreased with age (age: χ2 = 27.39; p < 0.001; φ = 1.17; Fig. 2I), suggesting that the ability to acquire or learn the initial discrimination improved with repeated experiencein the reversal-learning task. This, however, did not fully explain the age-related improvement in reversal performance, as age remained a significant factor when the number of trials required to achieve the first reversal was included in the model (age: χ2 = 25.32; p < 0.001; φ = 1.13). Age was also a significant factor in the model examining the number of trials that rats required to achieve the second reversal (χ2 = 43.84; p < 0.001; φ = 1.48;Fig. 2J).

To determine whether the age-related increase in reversal performance were linked to alterations in the influence of positive and/or negative outcomes on choice behavior, the regression coefficients obtained with the logistic regression were compared across the ages. The sex × trial-lag × age three-way interaction was not significant (χ2 = 4.13; p = 0.25; φ = 0.45), but the trial-lag × age interaction was significant (χ2 = 62.80; p < 0.001; φ = 1.77). Post hoc analyses only revealed a significant effect of age at trial t-1 (χ2 = 88.85; p < 0.001; φ = 2.11); age was not a significant predictor for the earlier trials in the past (e.g., t-2:t-4; χ2 < 0.86; p > 0.35). This result indicates that age-related differences in reward-guided behavior were not due differences in how outcomes in the distant past were being integrated in action values. The likelihood of rats staying with a rewarded choice increased with age (χ2 = 59.44; p < 0.001; β = 0.0001; 95% CI, 0.0009–0.0014) to a similar degree in both sexes (age × sex interaction: χ2 = 0.02; p = 0.88; φ = 0.03; Fig. 2K). The likelihood of rats staying with an unrewarded choice, however, did not significantly change with age (χ2 = 2.86; p = 0.09; φ = 0.27; Fig. 2L).

Reversal learning under a probabilistic schedule of reinforcement

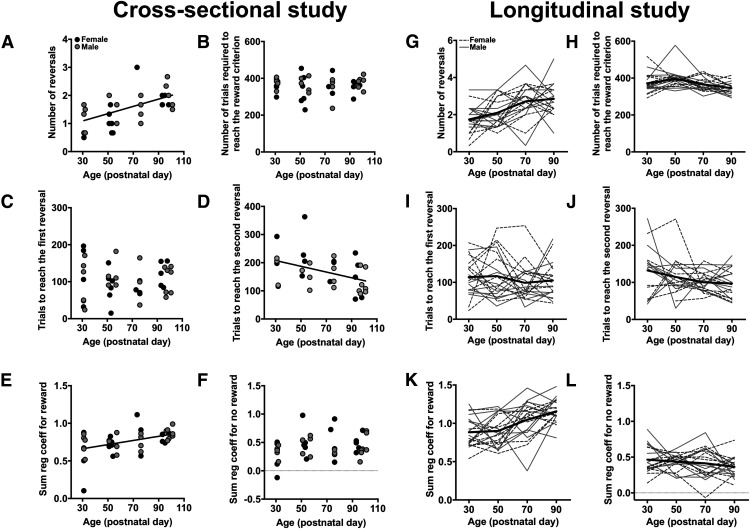

The performance of rats in the reversal-learning task under probabilistic schedules of reinforcement was then examined (Table 1). In the cross-sectional study, the number of reversals that rats achieved in a single session increased with age (χ2 = 18.19; p < 0.001; φ = 0.67) and similarly in both sexes (age × sex: χ2 = 0.40; p = 0.53; φ = 0.10; Fig. 3A). This age-related increase in the number of reversals completed was not due to differences in the number of trials that rats completed (χ2 = 0.88; p = 0.35; φ = 0.15; Fig. 3B) or in the number of trials rats required to achieve the first reversal (χ2 = 0.02; p = 0.90; φ = 0.02; Fig. 3C). However, the effect of age was significant for the number of trials that rats required to achieve the second reversal (χ2 = 6.59; p = 0.01; φ = 0.41; Fig. 3D), suggesting that the increase in reversal performance was specifically due to an improvement in the ability of rats to adjust their choices following the change in reinforcement contingencies. The logistic regression analysis showed that the interaction between trial lag and age was not significant (χ2 = 0.97; p = 0.81; φ = 0.16), but that age was a significant predictor for the likelihood of rats repeating a rewarded choice (χ2 = 7.33; p = 0.007; φ = 0.43; Fig. 3E). Age, however, was not a significant predictor in the likelihood of rats staying with an unrewarded choice (χ2 = 3.05; p = 0.08; φ = 0.28; Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

A–L, Performance in the probabilistic reversal-learning task in the cross-sectional study (A–F) and longitudinal study (G–L). A, The relationship between age and the average number of reversals completed in a single reversal-learning session. B, The relationship between age and the average number of trials required to achieve the reward criterion in a single session. C, The relationship between age and the number of trials required to reach the first reversal or to acquire the initial discrimination. D, The relationship between age and the number of trials rats required to reach the second reversal. E, The relationship between age and the sum of the regression coefficients for the “rewarded” predictor in the logistic regression model. F, The relationship between age and the sum of the regression coefficients for the “unrewarded” predictor in the logistic regression model. G, The average number of reversals completed in a single session at each of the four postnatal timepoints. H, The average number of trials required to achieve the reward criterion in a single session at each of the four postnatal timepoints. I, The number of trials required to reach the first reversal at each of the four postnatal timepoints. J, The number of trials required to reach the second reversal at each of the four postnatal timepoints. K, The sum of the regression coefficients for the rewarded predictor in the logistic regression model at each of the four postnatal timepoints. L, The sum of the regression coefficients for the unrewarded predictor in the logistic regression model at each of the four postnatal timepoints. Black circles, Female; gray circles, male; dotted black lines, female; solid gray lines, male; solid black line, average.

We then examined the performance of rats on the probabilistic task in the longitudinal study (Table 1). Similar to the results of the cross-sectional study, the number of reversals that rats were able to achieve in a single session increased with age (χ2 = 22.38; p < 0.001; φ = 1.06; Fig. 3G) and similarly in both sexes (age × sex: χ2 = 2.79; p = 0.10; φ = 0.37). The number of trials that rats required to achieve the reward criterion decreased with age (χ2 = 6.75; p = 0.009; φ = 0.58; Fig. 3H), and age remained a significant effect when the number of reversals rats performed and the number of trials completed were included in the model (χ2 = 24.02; p < 0.001; φ = 1.10). This increase in reversal performance was not driven by age-related changes in the ability of rats to acquire a discrimination, as age did not explain a significant amount of variance in the number of trials required to achieve the first reversal (χ2 = 0.61; p = 0.44; φ = 0.17; Fig. 3I). There was a nonsignificant, trend-level effect of age, however, in explaining variance in the number of trials required to achieve the second reversal (χ2 = 3.32; p = 0.07; φ = 0.41; Fig. 3J). This did not achieve statistical significance, in part, because several rats failed to reach criterion after the change in reinforcement probabilities (N = 8) and were excluded from this analysis. The analysis of regression coefficients from the logistic regression model for rewarded outcomes did not detect a significant sex × trial-lag × age interaction (χ2 = 1.12; p = 0.77; φ = 0.24), but did detect a significant trial-lag × age interaction (χ2 = 100.99; p < 0.001; φ = 2.25). Post hoc analyses, however, only detect a significant effect of age at trial lag 1 (τ = 1, χ2 = 66.38; p < 0.001; φ = 1.82); age was not a significant predictor for the earlier trials (τ = 2∼4, χ2 < 2.58; p > 0.10). The likelihood of rats staying with a rewarded choice increased with age (χ2 = 32.68; p < 0.001; φ = 1.28; Fig. 3K) and was lower in females compared with males (χ2 = 5.07; p = 0.02; φ = 0.50). The likelihood of rats staying with an unrewarded choice decreased with age (χ2 = 4.74; p = 0.03; φ = 0.49; Fig. 3L) with a trend-level differences detected between the sexes (χ2 = 3.53; p = 0.06; φ = 0.42) in which females were less likely to stay with an unrewarded choice compared with males.

Reinforcement-learning processes underlying age-related improvements in reversal learning

The age-related changes in reversal learning were remarkably similar between the cross-sectional and longitudinal studies and between the deterministic and probabilistic reinforcement schedules. This suggests that age-related improvements in reversal learning may be mediated by common reinforcement-learning mechanisms in both studies. To examine this, choice data in the deterministic and probabilistic reversal-learning task were fitted with the four reinforcement-learning models (see Materials and Methods). The BIC for each of these models was calculated for individual rats, and the sum of these BIC values is presented in Table 2 and Table 3. The BIC for the forgetting reinforcement-learning model was consistently lower compared with all other models at every age examined in the cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, indicating that the forgetting reinforcement-learning model best fit the rat choice data. The parameter estimates from this model (e.g., γ, Δ+, and Δ0) were averaged across the reinforcement schedules and compared across adolescent age.

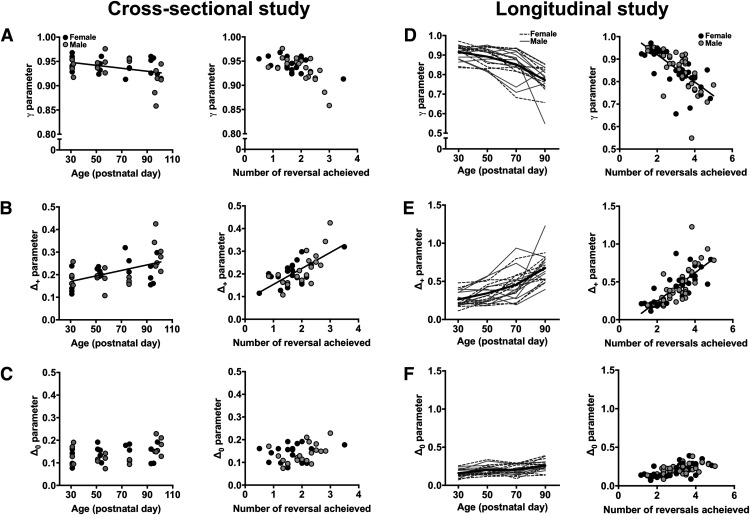

Age-related changes in the reinforcement-learning parameters were first examined in the cross-sectional study. The three-way interaction among sex × age × parameter was not significant (χ2 = 1.29; p = 0.53; φ = 0.18), but the age × parameter two-way interaction was significant (χ2 = 15.58; p < 0.001; φ = 0.62). Post hoc analyses revealed that as age increased across rats, the γ parameter decreased (χ2 = 5.09; p = 0.02; φ = 0.36; Fig. 4A) and the Δ+ parameter increased (χ2 = 10.96; p = 0.001; φ = 0.52; Fig. 4B). The Δ0 parameter, however, did not significantly change with age (χ2 = 1.79; p = 0.18; φ = 0.21; Fig. 4C). We then conducted a multiple regression analysis to determine whether these parameter estimates explained unique portions of variance in reversal performance. The Δ+ parameter was the only significant predictor in the regression model, explaining 46% of the variance in the number of reversals rats completed (F(1,38) = 32.86; p < 0.001; Fig. 4A–C, right panels).

Figure 4.

A–F, Age-related changes in reinforcement-learning processes in the cross-sectional study (A–C) and longitudinal study (D–F). A, Left, The relationship between age and the γ parameter. Right, The relationship between the average number of reversals achieved in the deterministic and probabilistic reversal-learning task and individual differences in the γ parameter. B, Left, The relationship between age and the Δ+ parameter. Right, The relationship between the average number of reversals achieved in the deterministic and probabilistic reversal-learning task and individual differences in the Δ+ parameter. C, Left, The relationship between age and the Δ0 parameter. Right, The relationship between the average number of reversals achieved in the deterministic and probabilistic reversal-learning task and individual differences in the Δ0 parameter. D, Left, The γ parameter estimate at each of the four postnatal timepoints. Right, The relationship between the average number of reversals achieved in the deterministic and probabilistic reversal-learning task and individual differences in the γ parameter. E, Left, The Δ+ parameter estimate at each of the four postnatal timepoints. Right, The relationship between the average number of reversals achieved in the deterministic and probabilistic reversal-learning task and individual differences in the Δ+ parameter. F, Left, The Δ0 parameter estimate at each of the four postnatal timepoints. Right, The relationship between the average number of reversals achieved in the deterministic and probabilistic reversal-learning task and individual differences in the Δ0 parameter. Black circles, Female; gray circles, male; dotted black lines, female; solid gray lines, male; solid black line, average.

We then examined age-related changes in the reinforcement-learning parameters collected in the longitudinal study. The sex × age × parameter three-way interaction was not significant (χ2 = 0.88; p = 0.65; φ = 0.21), but the age × parameter interaction was significant (χ2 = 99.57; p < 0.001; φ = 2.23). Post hoc analyses indicated that all parameters changed with age: the Δ+ and Δ0 parameters increased with age (χ2 > 27.70; p < 0.001), and the γ parameter decreased (χ2 = 87.17; p < 0.001; φ = 2.09; Fig. 4D–F). We then conducted a nested regression analysis to determine whether the parameters explained unique portions of variance in reversal performance. Only the γ and Δ+ parameters were significant predictors in the model, explaining 85% of the variance in the number of reversals that rats completed (γ parameter: χ2 = 46.28; p < 0.001; φ = 1.52; Δ+ parameter: χ2 = 99.74; p < 0.001; φ = 2.23; Fig. 4D–F, right panels).

These results, together, indicate that the increase in performance that was observed in both the cross-sectional and longitudinal conditions was associated with age-related increases in value updating after positive outcomes: the Δ+ parameter increased with age in both experimental conditions and was correlated with reversal performance.

Adolescent reversal-learning trajectories predict reversal learning in adulthood

Individual differences in reversal-learning trajectories during adolescence, which may be linked to specific neurodevelopmental mechanisms, could be predictive of reversal performance in adulthood. To test this hypothesis, we continued to assess reversal-learning performance of the longitudinal rats into adulthood (P130, P150, and P170; Fig. 5A–C) and examined the predictive relationship between reversal-learning trajectories in adolescent and reversal-learning performance in adulthood.

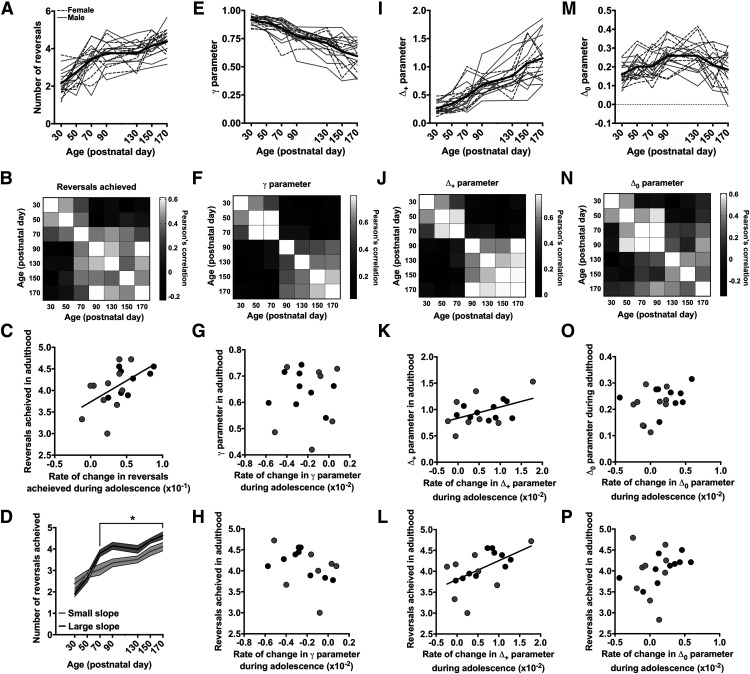

Figure 5.

Adolescent reversal-learning trajectories predict individual differences in reversal-learning performance in adulthood. A, The average number of reversals rats achieved in a single session across the seven postnatal timepoints. B, A matrix of Pearson's correlation coefficients for the number of reversals achieved at each of the postnatal timepoints. Lighter boxes indicate a large, positive correlation; darker boxes indicate a small, negative correlation. C, The relationship between the slope of change in the number of reversals achieved between P30 and P70 and the average number of reversals achieved between P130 and P170. D, The number of reversal rats achieved in rats that a small slope (gray line) compared with a large slope (black line) in adolescence. E, The γ parameter estimate across the seven postnatal timepoints. F, A matrix of Pearson's correlation coefficients for the γ parameter at each of the postnatal timepoints. G, The relationship between the slope of change in the γ parameter between P30 and P70 and the average γ parameter estimate between P130 and P170. H, The relationship between the slope of change in the γ parameter between P30 and P70 and the average number of reversals achieved between P130 and P170. I, The Δ+ parameter estimate across the seven postnatal timepoints. J, A matrix of Pearson's correlation coefficients for the Δ+ parameter at each of the postnatal timepoints. K, The relationship between the slope of change in the Δ+ parameter between P30 and P70 and the average Δ+ parameter estimate between P130 and P170. L, The relationship between the slope of change in the Δ+ parameter at P30 and P70 and the average number of reversals achieved between P130 and P170. M, The Δ0 parameter estimate across the seven postnatal timepoints. N, A matrix of Pearson's correlation coefficients for the Δ0 parameter at each of the postnatal timepoints. O, The relationship between the slope of change in the Δ0 parameter between P30 and P70 and the average Δ0 parameter estimate between P130 and P170. P, The relationship between the slope of change in the Δ0 parameter between P30 and P70 and the average number of reversals achieved between P130 and P170.

First, we generated a correlation matrix of the relationships among the number of reversals achieved at each of the seven testing ages (Fig. 5B). The matrix revealed two distinct clusters: one included performance at P30, P50, and P70, and another one included P90, P130, P150, and P170. Indeed, a PCA revealed that reversal performance at P30, P50, and P70 positively loaded onto a single component that explained 24% of the variance. In contrast, reversal performance at P90, P130, P150, and P170 positively loaded onto a different component that explained 40% of the variance. This suggests that reversal performance during early adolescence was largely independent of reversal performance of the same animals in adulthood. We hypothesized that although absolute reversal performance in adolescence was not predictive of performance in adulthood (Fig. 5B), the degree of change in reversal performance during early adolescence might be. To test this, we calculated the slope between reversal performance and adolescent age (e.g., P30, P50, and P70) for individual rats and examined whether the slope of change in adolescent reversal performance was predictive of reversal performance in adulthood (e.g., P130, P150, and P170). Data collected at P90 were excluded from this analysis because this age in the rat is at the boundary between late adolescence and young adulthood. Nevertheless, the same pattern of results was observed when data at P90 were included in the analysis. There was a positive relationship between these variables (R2 = 0.30; p = 0.02; Fig. 5C), indicating that the rate of improvement in reversal performance during adolescence was predictive of reversal performance in adulthood. We also conducted a median-split based on whether the slope of change during adolescence was small or large and examined whether age-related changes in reversal performance differed between the two groups. As predicted, the age × group interaction was significant (χ2 = 5.42; p = 0.02; φ = 0.52): post hoc analyses indicated that significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed between the groups at P70 and throughout adulthood (Fig. 5D).

Next, the choice data collected in adulthood were analyzed with the forgetting reinforcement-learning model and a similar analysis was conducted for each of the three parameter estimates derived from this model. We first examined age-related changes in the γ parameter (Fig. 5E). The correlation matrix for the γ parameter revealed a pattern strikingly similar to that observed in the number of reversals achieved (Fig. 5F): the γ parameter estimates at P30, P50, and P70 were strongly related to each other, as was the γ parameter estimates collected at P90, P130, P150, and P170. The γ parameter estimates in adolescence, however, were not related to those in adulthood. A PCA confirmed this segregation: γ parameter estimates at P30, P50, and P70 uniquely loaded onto one component, explaining 44% of the variance, whereas the γ parameter estimate at P90, P130, P150, and P170 loaded onto a different component that explained 29% of the variance. We then calculated the slope of change in the γ parameter during adolescence and examined the relationship between the γ parameter slope and γ parameter in adulthood. Unlike reversal performance, the slope of change in the γ parameter during adolescence did not predict the γ parameter in adulthood (R2 = 0.008; p = 0.73; Fig. 5G). Moreover, the degree of change in the γ parameter during adolescence did not predict reversal performance in adulthood (R2 = 0.16; p = 0.12; Fig. 5H).

We then examined age-related changes in the Δ+ parameter (Fig. 5I). The correlation matrix for the Δ+ parameter indicated that the Δ+ parameter estimates collected at P30, P50, and P70 were strongly related to one another, as were the Δ+ parameter estimates collected at P90, P130, P150, and P170. However, the Δ+ parameter estimates in adolescence were not correlated with those in adulthood (Fig. 5J). A PCA confirmed this segregation, indicating that the Δ+ parameter estimates at P30, P50, and P70 uniquely loaded onto one component that explained 29% of the variance, whereas the Δ+ parameter estimates at P90, P130, P150, and P170 loaded onto a different component that explained 47% of the variance. We then examined the relationship between the slope of change in the Δ+ parameter during adolescence with the Δ+ parameter estimates in adulthood. The degree of change in the Δ+ parameter during adolescence predicted the Δ+ parameter estimate in adulthood (R2 = 0.21; p = 0.05; Fig. 5K): rats who had a more significant increase in the Δ+ parameter in adolescence had a larger Δ+ parameter in adulthood. Moreover, the degree of change in the Δ+ parameter during adolescence was correlated with the degree of change in reversal performance (e.g., the number of reversals completed) during adolescence (R2 = 0.34; p = 0.009) and reliably predicted reversal performance in adulthood (R2 = 0.31; p = 0.02; Fig. 5L). These data suggest that improvements in value updating after positive outcomes during adolescence predicted individual differences in reversal performance in adulthood.

Finally, age-related changes in the Δ0 parameter were examined (Fig. 5M). The correlation matrix for the Δ0 parameter did not segregate age groups as clearly as observed with the γ and Δ+ parameters (Fig. 5N). The PCA identified three, rather than two, significant components that segregated into three distinct age groups: the Δ0 parameter at P30 and P50 positively loaded onto component 2 (explaining 26% of the variance); the Δ0 parameter at P70, P90, and P130 loaded onto component 1 (explaining 37% of the variance); and the Δ0 parameter at P150 and P170 loaded onto components 1 and 3 (explaining 15% of the variance). Nevertheless, we performed the same analysis as we did for the γ and Δ+ parameters. The degree of change in the Δ0 parameter during adolescence did not predict the Δ0 parameter estimate in adulthood (R2 = 0.21; p = 0.05; Fig. 5O) or reversal performance in adulthood (R2 = 0.06; p = 0.31; Fig. 5P). These results, collectively, indicate that selective improvements in value updating after positive outcomes during adolescence are predictive of reversal performance in adulthood.

Discussion

The findings from the present study provide new evidence that age-related improvements in adaptive choice behavior assessed in a reversal-learning task are linked to changes in select reinforcement-learning processes. The number of reversals that rats completed under deterministic and probabilistic schedules of reinforcement increased across adolescent development in both male and female rats, and this change was due to improvements in value updating after positive outcomes. Moreover, the rate of increase in reversal performance during adolescence is predictive of reversal performance in adulthood. Our findings provide a novel framework for subsequent neurobiological studies aimed at understanding the molecular and systems-level neurodevelopmental mechanisms underlying adaptive choice behavior.

Performance in the reversal-learning task increases during adolescence

The age-related improvement in reversal-learning performance observed in the present study is consistent with those previously observed in humans (van der Schaaf et al., 2011). We found that the ability to adjust choice behavior in response to changes in reinforcement contingencies increased between postnatal days 30 and 90 in both the cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. These improvements were not specific to the schedule of reinforcement used, nor were they explained by differences in the ability of rats to acquire the initial discrimination. This indicates that the age-related changes in reversal performance were due specifically to improvements in the ability of rats to adjust their behavior following a change in reinforcement contingencies. The magnitude of change in reversal performance during adolescence was greater in rats that had been repeatedly tested compared with those in the cross-sectional study. Nevertheless, we also observed a strong relationship between age and reversal performance in rats not repeatedly tested on the reversal-learning task, suggesting that the age-related changes in reversal performance are likely linked to neurodevelopmental alterations that occur during this developmental period.

Our computational approach revealed that the age-related changes in reversal performance were due to improvements in value updating for positive outcomes: rats were more likely to use positive outcomes to guide their subsequent choices as they aged. This finding is consistent with data in humans showing that adolescents are less likely than adults to repeat a rewarded action (Javadi et al., 2014). Age-related changes in negative-outcome updating were not consistent between cross-sectional and longitudinal studies: no relationship was observed between age and the Δ0 parameter in the cross-sectional study, but we observed a significant increase in the Δ0 parameter in the longitudinal study. This might suggest that value updating for negative outcomes might change with experience in the task and/or emerges later in development. Moreover, we did not observe a consistent effect of sex in our analyses; the only statistically significant effect of sex was observed in the longitudinal study under the probabilistic schedule of reinforcement. We found that female rats were less likely to repeat a previous choice, regardless of the outcome. Recent work has suggested that male and female mice use different strategies in a two-choice visual discrimination paradigm (Chen et al., 2020), so it is possible that the subtle sex differences observed here may be reflective of sex-dependent differences in learning strategies.

We also observed an age-related decline in the retention, or decay, of action values (e.g., γ parameter) in both the cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, indicating that as rats aged, choice behavior was more influenced by choices and outcomes from recent trials than by those in the distant past. Interestingly, variation in the γ parameter estimate explained a significant amount of variance in reversal performance only in the longitudinal study, but not in the cross-sectional study. This discrepancy between the two studies might be accounted for by differences in meta-learning, or learning when to learn (Doya, 2002; Soltani et al., 2006). Meta-learning is hypothesized to be the mechanism by which model-free reinforcement-learning mechanisms can be adjusted for adapting to new environments or contexts (Wang et al., 2016). Repeated experience with the reversal-learning paradigm may recruit meta-learning mechanisms that would not have been engaged with limited experience. The influence of the γ parameter on reversal performance in the longitudinal study and not in the cross-sectional study might, therefore, reflect meta-learning.

Age-related changes in reversal-learning performance during adolescence may enable an organism to learn about the environment and then to exploit this knowledge to obtain food and/or access to reproductive opportunities (Kelley et al., 2004; McCormick and Telzer, 2017). Our data indicate that during early adolescence rats were more likely to switch their choices following a positive outcome (i.e., a lower Δ+ parameter), suggesting that they were not using the rewarded outcome to guide their choice behavior, as was observed in older rats. Although our previous work has indicated that disruptions in positive value updating are a risk factor for drug use in adult rats (Groman et al., 2020), a lower Δ+ parameter in younger rats may be adaptive. Adolescence is period associated with greater exploratory and novelty-seeking behaviors (Kelley et al., 2004; Forbes and Dahl, 2010), which may help juveniles to develop skills for independence and survival in the absence of the parent (Kelley et al., 2004). The age-related change in the Δ+ parameter that we observed in the current study may, therefore, reflect developmental changes in exploration–exploitation trade-off that has been observed in adolescent humans (Somerville et al., 2017).

Neurodevelopment and decision-making in adolescence

The brain undergoes morphologic and functional transformations during adolescence (Casey et al., 2008; Spear, 2013). Human neuroimaging studies have observed changes in structure, function, and connectivity during adolescence (Giedd et al., 1999; Sowell et al., 1999; Thompson et al., 2001; Toga et al., 2006; Lenroot et al., 2007; Ernst et al., 2015; Karlsgodt et al., 2015; Stevens, 2016) that appear to parallel the time course of decision-making improvements (van der Schaaf et al., 2011). The rate of change, however, varies across brain regions, and the developmental mismatch between subcortical and cortical maturation has been proposed to underlie the increase in risky behaviors and poor decision-making that are typically observed in adolescents (Casey et al., 2008, 2016; Mills et al., 2014).

One of the last regions to mature during adolescence is the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), a region critically involved in reversal learning (Schoenbaum et al., 2003; Rudebeck and Murray, 2008; Walton et al., 2010; Rudebeck et al., 2017) and reinforcement learning (Kennerley and Wallis, 2009; Sturman and Moghaddam, 2011; Massi et al., 2018; Costa and Averbeck, 2020). Our recent work using a reversal-learning paradigm has demonstrated that select reinforcement-learning mechanisms are controlled by anatomically distinct orbitofrontal circuits (Groman et al., 2019), which are known to mature during adolescence (Asato et al., 2010; Ladouceur et al., 2012; Karlsgodt et al., 2015). Individual differences in reversal-learning trajectories during adolescence may be linked to differences in the maturation of specific neural circuits (Asato et al., 2010; Ladouceur et al., 2012; Karlsgodt et al., 2015; Anandakumar et al., 2018; Gee et al., 2018). Based on our previous work (Groman et al., 2019), we hypothesize that the increase in positive value updating observed here is linked to developmental changes in the amygdala–OFC circuitry observed in human neuroimaging studies (Gee et al., 2013).

In addition to the circuit-based changes, many neurotransmitter systems also transform during adolescence (Wahlstrom et al., 2010; Pitzer, 2019). For example, the density of dopamine D1 and D2 receptors peaks during early adolescence and then rapidly declines (Teicher et al., 1995; Andersen et al., 2000). We and others have found that the variation in dopaminergic markers is related to reversal-learning performance in adult humans and monkeys (Clatworthy et al., 2009; Cools et al., 2009; Groman et al., 2011, 2016). It is possible, therefore, that the age-related alterations in reversal learning observed in the current study are due to the maturation of the dopamine system. Indeed, adolescent rats have lower dopamine availability in the dorsal striatum (Matthews et al., 2013) and reduced reward-mediated signaling in putative midbrain dopamine neurons (Kim et al., 2016) that are likely to be involved in the age-related changes in positive value updating.

Implications for neurodevelopmental mechanisms of mental illness

The peak onset age for many mental disorders is adolescence (Chambers et al., 2003; Paus et al., 2008), and these symptoms might emerge as a result of deviations in the normal developmental changes during this period. Previous work has demonstrated that reversal learning is disrupted in adults with mental illness (Fillmore and Rush, 2006; Waltz and Gold, 2007; Chamberlain et al., 2008). However, the latent behavioral factors contributing to maladaptive reversal performance may differ between disorders and involve distinct neural mechanisms that develop during adolescence. Identifying the neurobiological adaptations underlying alterations in reversal-learning performance during adolescence could provide critical insights into the pathology of these disorders.

Summary

Our behavioral protocol provides a unique platform for probing the neurodevelopmental mechanisms underlying adaptive choice behavior in normal and pathologic states. We provide insights into how reinforcement-learning mechanisms change in adolescent development and into adulthood, and show evidence that adolescent reversal-learning trajectories can predict reversal-learning performance in adulthood. The use of our translationally analogous reversal-learning task and computational approaches combined with sophisticated neurobiological techniques in rodent models could elucidate key components of adolescent brain function.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a Yale/ National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Neuroproteomics Center Pilot Research Project Grant (to S.M.G.) through a Public Health Service grant from NIDA (Grant P30-DA-018343), a Public Health Service grant from NIDA (Grant DA-041480 to S.M.G., D.L., and J.R.T.), a Public Health Service grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant R21-MH-120615 to S.M.G.), NARSAD Young Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (to S.M.G.), and funding provided by the State of Connecticut.

D.L. is a cofounder of Neurogazer Inc. The authors declare no other competing financial interests.

References

- Anandakumar J, Mills KL, Earl EA, Irwin L, Miranda-Dominguez O, Demeter DV, Walton-Weston A, Karalunas S, Nigg J, Fair DA (2018) Individual differences in functional brain connectivity predict temporal discounting preference in the transition to adolescence. Dev Cogn Neurosci 34:101–113. 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Thompson AT, Rutstein M, Hostetter JC, Teicher MH (2000) Dopamine receptor pruning in prefrontal cortex during the periadolescent period in rats. Synapse 37:167–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asato MR, Terwilliger R, Woo J, Luna B (2010) White matter development in adolescence: a DTI study. Cereb Cortex 20:2122–2131. 10.1093/cercor/bhp282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballinger GA. (2004) Using generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Org Res Methods 7:120–150. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley-Levenson E, Galván A (2014) Neural representation of expected value in the adolescent brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:1646–1651. 10.1073/pnas.1319762111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barraclough DJ, Conroy ML, Lee D (2004) Prefrontal cortex and decision making in a mixed-strategy game. Nat Neurosci 7:404–410. 10.1038/nn1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ, Robbins TW (2012) Decision-making in the adolescent brain. Nat Neurosci 15:1184–1191. 10.1038/nn.3177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, Menzies L, Hampshire A, Suckling J, Fineberg NA, del Campo N, Aitken M, Craig K, Owen AM, Bullmore ET, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ (2008) Orbitofrontal dysfunction in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and their unaffected relatives. Science 321:421–422. 10.1126/science.1154433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Galván A, Somerville LH (2016) Beyond simple models of adolescence to an integrated circuit-based account: a commentary. Dev Cogn Neurosci 17:128–130. 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Jones RM, Hare A (2008) The Adolescent Brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1124:111–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers RA, Taylor JR, Potenza MN (2003) Developmental neurocircuitry of motivation in adolescence: a critical period of addiction vulnerability. Am J Psychiatry 160:1041–1052. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CS, Ebitz RB, Bindas SR, Redish AD, Hayden BY, Grissom NM (2020) Divergent strategies for learning in males and females. bioRxiv. Advance online publication. Retrieved March 10, 2020. doi: 10.1101/852830 10.1101/852830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakou A, Gershman SJ, Niv Y, Simmons A, Brammer M, Rubia K (2013) Neural and psychological maturation of decision-making in adolescence and young adulthood. J Cogn Neurosci 25:1807–1823. 10.1162/jocn_a_00447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatworthy PL, Lewis SJ, Brichard L, Hong YT, Izquierdo D, Clark L, Cools R, Aigbirhio FI, Baron JC, Fryer TD, Robbins TW (2009) Dopamine release in dissociable striatal subregions predicts the different effects of oral methylphenidate on reversal learning and spatial working memory. J Neurosci 29:4690–4696. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3266-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, Frank MJ, Gibbs SE, Miyakawa A, Jagust W, D'Esposito M (2009) Striatal dopamine predicts outcome-specific reversal learning and its sensitivity to dopaminergic drug administration. J Neurosci 29:1538–1543. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4467-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa VD, Averbeck BB (2020) Primate orbitofrontal cortex codes information relevant for managing explore-exploit tradeoffs. J Neurosci 40:2553–2561. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2355-19.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidow JY, Foerde K, Galván A, Shohamy D (2016) An upside to reward sensitivity: the hippocampus supports enhanced reinforcement learning in adolescence. Neuron 92:93–99. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan P, Daw ND (2008) Decision theory, reinforcement learning, and the brain. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 8:429–453. 10.3758/CABN.8.4.429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker JH, Otto AR, Daw ND, Hartley CA (2016) From creatures of habit to goal-directed learners: tracking the developmental emergence of model-based reinforcement learning. Psychol Sci 27:848–858. 10.1177/0956797616639301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doya K. (2002) Metalearning and neuromodulation. Neural Netw 15:495–506. 10.1016/S0893-6080(02)00044-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Torrisi S, Balderston N, Grillon C, Hale EA (2015) fMRI functional connectivity applied to adolescent neurodevelopment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 11:361–377. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersche KD, Roiser JP, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ (2008) Chronic cocaine but not chronic amphetamine use is associated with perseverative responding in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 197:421–431. 10.1007/s00213-007-1051-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Rush CR (2006) Polydrug abusers display impaired discrimination-reversal learning in a model of behavioural control. J Psychopharmacol 20:24–32. 10.1177/0269881105057000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, Dahl RE (2010) Pubertal development and behavior: hormonal activation of social and motivational tendencies. Brain Cogn 72:66–72. 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, Seeberger LC, O'Reilly RC (2004) By carrot or by stick: cognitive reinforcement learning in parkinsonism. Science 306:1940–1943. 10.1126/science.1102941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M, Steinberg L (2005) Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: an experimental study. Dev Psychol 41:625–635. 10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee DG, Humphreys KL, Flannery J, Goff B, Telzer EH, Shapiro M, Hare TA, Bookheimer SY, Tottenham N (2013) A developmental shift from positive to negative connectivity in human amygdala-prefrontal circuitry. J Neurosci 33:4584–4593. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3446-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee DG, Bath KG, Johnson CM, Meyer HC, Murty VP, van den Bos W, Hartley CA (2018) Neurocognitive development of motivated behavior: dynamic changes across childhood and adolescence. J Neurosci 38:9433–9445. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1674-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahremani DG, Tabibnia G, Monterosso J, Hellemann G, Poldrack RA, London ED (2011) Effect of modafinil on learning and task-related brain activity in methamphetamine-dependent and healthy individuals. Neuropsychopharmacology 36:950–959. 10.1038/npp.2010.233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, Castellanos FX, Liu H, Zijdenbos A, Paus T, Evans AC, Rapoport JL (1999) Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nat Neurosci 2:861–863. 10.1038/13158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groman SM, Lee B, London ED, Mandelkern MA, James AS, Feiler K, Rivera R, Dahlbom M, Sossi V, Vandervoort E, Jentsch JD (2011) Dorsal striatal D2-like receptor availability covaries with sensitivity to positive reinforcement during discrimination learning. J Neurosci 31:7291–7299. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0363-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groman SM, Smith NJ, Petrullli JR, Massi B, Chen L, Ropchan J, Huang Y, Lee D, Morris ED, Taylor JR (2016) Dopamine D3 receptor availability is associated with inflexible decision making. J Neurosci 36:6732–6741. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3253-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groman SM, Rich KM, Smith NJ, Lee D, Taylor JR (2018) Chronic exposure to methamphetamine disrupts reinforcement-based decision making in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 43:770–780. 10.1038/npp.2017.159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groman SM, Keistler C, Keip AJ, Hammarlund E, DiLeone RJ, Pittenger C, Lee D, Taylor JR (2019) Orbitofrontal circuits control multiple reinforcement-learning processes. Neuron 103:734–746.e3. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.05.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groman SM, Hillmer AT, Liu H, Fowles K, Holden D, Morris ED, Lee D, Taylor J (2020) Midbrain D3 receptor availability predicts escalation in cocaine self-administration. Biol Psychiatry S0006-3223:30112–30118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley CA, Somerville LH (2015) The neuroscience of adolescent decision-making. Curr Opin Behav Sci 5:108–115. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser TU, Iannaccone R, Walitza S, Brandeis D, Brem S (2015) Cognitive flexibility in adolescence: neural and behavioral mechanisms of reward prediction error processing in adaptive decision making during development. Neuroimage 104:347–354. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Doya K (2009) Validation of decision-making models and analysis of decision variables in the rat basal ganglia. J Neurosci 29:9861–9874. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6157-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javadi AH, Schmidt DHK, Smolka MN (2014) Adolescents adapt more slowly than adults to varying reward contingencies. J Cogn Neurosci 26:2670–2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, Queen B, Lowry R, Olsen EO, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, Lim C, Yamakawa Y, Brener N, Zaza S (2016) Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ 65:1–174. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6506a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsgodt KH, John M, Ikuta T, Rigoard P, Peters BD, Derosse P, Malhotra AK, Szeszko PR (2015) The accumbofrontal tract: diffusion tensor imaging characterization and developmental change from childhood to adulthood. Hum Brain Mapp 36:4954–4963. 10.1002/hbm.22989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE, Schochet T, Landry CF (2004) Risk taking and novelty seeking in adolescence: introduction to part I. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1021:27–32. 10.1196/annals.1308.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennerley SW, Wallis JD (2009) Encoding of reward and space during a working memory task in the orbitofrontal cortex and anterior cingulate sulcus. J Neurophysiol 102:3352–3364. 10.1152/jn.00273.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustün TB (2007) Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry 20:359–364. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Simon NW, Wood J, Moghaddam B (2016) Reward anticipation is encoded differently by adolescent ventral tegmental area neurons. Biol Psychiatry 79:878–886. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladouceur CD, Peper JS, Crone EA, Dahl RE (2012) White matter development in adolescence: the influence of puberty and implications for affective disorders. Dev Cogn Neurosci 2:36–54. 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. (2013) Decision making: from neuroscience to psychiatry. Neuron 78:233–248. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenroot RK, Gogtay N, Greenstein DK, Wells EM, Wallace GL, Clasen LS, Blumenthal JD, Lerch J, Zijdenbos AP, Evans AC, Thompson PM, Giedd JN (2007) Sexual dimorphism of brain developmental trajectories during childhood and adolescence. Neuroimage 36:1065–1073. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massi B, Donahue CH, Lee D (2018) Volatility facilitates value updating in the prefrontal cortex. Neuron 99:598–608.e4. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.06.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews M, Bondi C, Torres G, Moghaddam B (2013) Reduced presynaptic dopamine activity in adolescent dorsal striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology 38:1344–1351. 10.1038/npp.2013.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick EM, Telzer EH (2017) Adaptive adolescent flexibility: neurodevelopment of decision-making and learning in a risky context. J Cogn Neurosci 29:413–423. 10.1162/jocn_a_01061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKirdy J, Sussmann JE, Hall J, Lawrie SM, Johnstone EC, McIntosh AM (2009) Set shifting and reversal learning in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Psychol Med 39:1289–1293. 10.1017/S0033291708004935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Goddings A-L, Clasen LS, Giedd JN, Blakemore S-J (2014) The developmental mismatch in structural brain maturation during adolescence. Dev Neurosci 36:147–160. 10.1159/000362328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MR, Weiss VG, Beas BS, Morgan D, Bizon JL, Setlow B (2014) Adolescent risk taking, cocaine self-administration, and striatal dopamine signaling. Neuropsychopharmacology 39:955–962. 10.1038/npp.2013.295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niv Y. (2009) Reinforcement learning in the brain. J Math Psychol 53:139–154. 10.1016/j.jmp.2008.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nussenbaum K, Hartley CA (2019) Reinforcement learning across development: what insights can we draw from a decade of research? Dev Cogn Neurosci 40:100733. 10.1016/j.dcn.2019.100733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palminteri S, Kilford EJ, Coricelli G, Blakemore SJ (2016) The computational development of reinforcement learning during adolescence. PLoS Comput Biol 12:e1004953 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W. (2001) Akaike's information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics 57:120–125. 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00120.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN (2008) Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci 9:947–957. 10.1038/nrn2513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]