Abstract

Cancer progression including proliferation, metastasis, and chemoresistance has become a serious hindrance to cancer therapy. This phenomenon mainly derives from the innate insensitive or acquired resistance of cancer cells to apoptosis. Ferroptosis is a newly discovered mechanism of programmed cell death characterized by peroxidation of the lipid membrane induced by reactive oxygen species. Ferroptosis has been confirmed to eliminate cancer cells in an apoptosis-independent manner, however, the specific regulatory mechanism of ferroptosis is still unknown. The use of ferroptosis for overcoming cancer progression is limited. Noncoding RNAs have been found to play an important roles in cancer. They regulate gene expression to affect biological processes of cancer cells such as proliferation, cell cycle, and cell death. Thus far, the functions of ncRNAs in ferroptosis of cancer cells have been examined, and the specific mechanisms by which noncoding RNAs regulate ferroptosis have been partially discovered. However, there is no summary of ferroptosis associated noncoding RNAs and their functions in different cancer types. In this review, we discuss the roles of ferroptosis-associated noncoding RNAs in detail. Moreover, future work regarding the interaction between noncoding RNAs and ferroptosis is proposed, the possible obstacles are predicted and associated solutions are put forward. This review will deepen our understanding of the relationship between noncoding RNAs and ferroptosis, and provide new insights in targeting noncoding RNAs in ferroptosis associated therapeutic strategies.

Subject terms: Cancer prevention, Cancer therapy

Facts

Resistance to apoptosis has become the main obstacle for overcoming cancer progression.

Ferroptosis is a type of cell death characterized by excess reactive oxygen species and intracellular iron, and is totally different from apoptosis.

NcRNAs serve as important roles in biological processes of cancer.

Regulation of ncRNAs to ferroptosis has been partially discovered.

Open Questions

Can ferroptosis become the direction around which to design cancer therapy in future?

What are the roles of ncRNAs in regulation of ferroptosis?

Can ncRNAs become markers to filter cancer patients who are fit for ferroptosis therapy or therapeutic targets of ferroptosis inducers?

Introduction

Cancer progression including proliferation, metastasis and chemoresistance to drugs, has become serious obstacles in cancer therapy1. Although multiple therapeutic manners including operation, targeted therapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy have shown satisfactory performance, progression occurs since cancer cells dysregulate apoptosis pathways via various manners2,3. Therefore, new types of cancer therapy or drugs that eliminate cancer cells are urgently needed.

Ferroptosis is a type of programmed cell death discovered in 20124. Unlike apoptosis, ferroptosis is characterized by excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) and intracellular iron5. Superabundant ROS induces peroxidation and disintegration of lipid membrane and cell death6. Regulation of ferroptosis mainly depends on neutral reaction between reduced glutathione (GSH) and ROS7. The exchange of glutamate and cystine is mediated by systemXc−, which is composed of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) and solute carrier family 3 member 2 (SLC3A2), and offers the substrate cystine for GSH synthesis8,9. Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) catelyzes interaction between GSH and ROS to reduce intracellular oxidative stress10. Ferroptosis inducers can be divided into two classes based on regulation of neutral reaction to ROS. Class I ferroptosis inducers such as sorafenib, erastin and sulfasalazine, serve as blockers of systemXc− and result in a drop of GSH levels11,12. Class II ferroptosis inducers such as RSL3, FIN56, and ML162, inhibit function of GPX413,14. Numerous studies have confirmed that ferroptosis inducers such as RSL3 and sorafenib eliminates cancer cells15,16. In addition, induction of ferroptosis via erastin and sulfasalazine improved effect of cytarabine and doxorubicin, and overcame cisplatin resistance of head and neck cancer17,18. This suggests that ferroptosis may become a new mechanism around which to design cancer therapy. However, use of ferroptosis in cancer therapy still faces obstacles. First, the specific mechanisms underlying ferroptosis and the interaction between ferroptosis and other processes, such as apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy are not totally known, so how to control ferroptosis in cancer is in dark. Second, ferroptosis occurs in normal cells. Ferroptosis has been shown to induce the elimination of nerve cells in Parkinson’s disease19. In addition, in acute kidney injury, ferroptosis participated in the death of renal tubular epithelial cells20. Therefore, use of ferroptosis inducers may generate complications. New regulatory factors should be recognized to understand the true appearance of ferroptosis in cancer.

Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) are RNAs that account for nearly 98% of transcriptome21. According to length and shapes, ncRNAs are divided into various types including microRNAs (miRNAs), PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), long ncRNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), transfer RNAs (tRNAs), and ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs)22,23. NcRNAs participate in regulation of tumorigenesis via various biological processes such as chromatin modification, alternative splicing, competition with endogenous RNAs and interaction with proteins24,25. For example, miR-675-5p promoted the metastasis of colorectal cancer cells via modulation of P5326. Moreover, lncRNA HOTAIR served as an enhancer in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of breast cancer cells via competing with BRCA127. In addition, circFOXO3 enhanced progression of prostate cancer through sponging miR-29a-3p28. However, roles of ncRNAs in ferroptosis have not been fully determined.

In this review, we focus on summarizing the ncRNAs which have been found to associate with ferroptosis regulators GSH, iron, nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (NRF2) and ROS in cancer5. Moreover, we predict the obstacles that may limit the exploration of ncRNAs in ferroptosis in cancer therapy and offer advice for future studies. We believe that a comprehensive understanding of the interactions between ncRNAs and ferroptosis may benefit clinical therapeutics to cancer

MiRNAs and ferroptosis

MiRNAs exhibit functions by binding to the 3′-untranslated regions of target mRNAs and suppressing their expression29. Some studies have revealed a relationship between miRNAs and ferroptosis. In radioresistant cells, miR-7-5p inhibited ferroptosis via downregulating mitoferrin and thus reducing iron levels30. Furthermore, miR-9 and miR-137 enhanced ferroptosis via reduction of intracellular GSH levels, miR-9 inhibited synthesis of GSH and miR-137 suppressed solute carrier family 1 member 5 (SLC1A5), a component of systemXc−31. Moreover, miR-6852 which was regulated by lncRNA Linc00336, inhibited growth of lung cancer cells via promoting ferroptosis32. In the following sections, we will discuss the interactions between miRNAs and GSH, iron and NRF2 in cancer cells. The information of altered miRNAs in ferroptosis has been listed (Supplementary Table 1).

MiRNAs and GSH

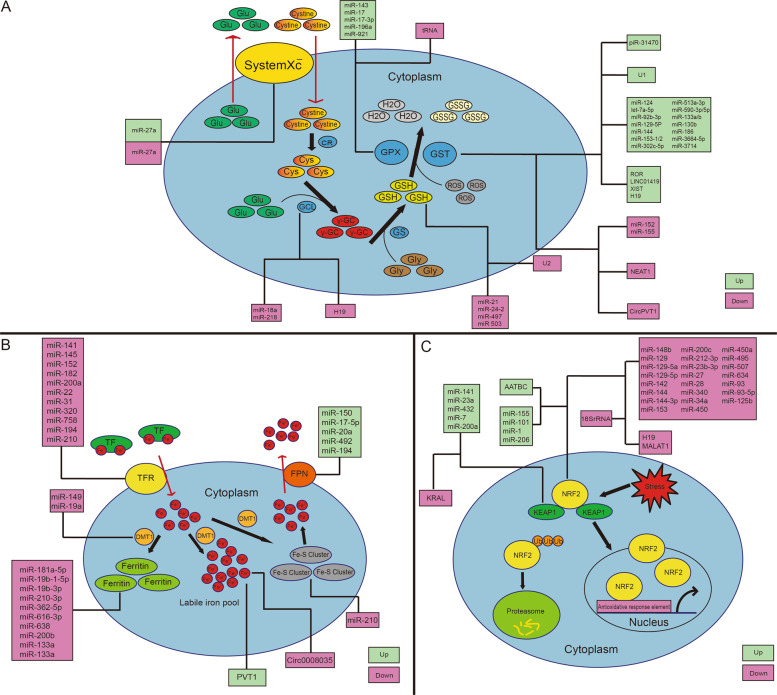

GSH is a scavengerof ROS and protects lipid membrane33. Under physiological conditions, concentration of reduced GSH is about 10–100-fold more prevalent than the oxidized form. Under oxidative stress, reduced GSH is converted to oxidized form34. Biosynthesis of GSH involves three steps: exchange of glutamic acid and cystine induced by systemXc−; synthesis of 𝛾-glutamylcysteine by glutamic acid and cysteine catalyzed via 𝛾-glutamylcysteine ligase (GCL); and synthesis of GSH via 𝛾-glutamylcysteine and glycine catalyzed by GSH synthetase35. Function of GSH includes detoxification of exogenous or endogenous dangerous compounds catalyzed by GSH-S-transferases (GSTs) and GPXs36. Current knowledge on relation between GSH and cancer are summarized in Table 1, and the schematic diagram of these interactions is shown in Fig. 1a. MiR-18a and miR-218 decreased GSH levels via targeting GCL in hepatocellular carcinoma and bladder cancer37,38. Furthermore, in hepatocellular carcinoma and lung cancer, miR-152 and miR-155 decreased GSH levels via targeting GST39,40. In addition, miR-326 and miR-27a inhibited GSH levels in cancer cells via targeting other factors such as pyruvate kinase m 2 (PKM2), SLC7A11 and zinc finger and BTB domain containing 10 (ZBTB10)41–43. Additionally, downregulation of GSH by miRNAs such as miR-21, miR-24-2, miR-497 and miR‑503 has been observed in different cancer types, however, the specific mechanisms were not explored44–47. These findings indicate that miRNAs repress GSH levels via control of synthesis and consumption. The upregulation of GSH induced by miRNAs has been well-explored. GST was targeted by different miRNAs including miR-124, let-7a-5p, miR-92b-3p, miR-129-5P, miR-144, miR-153-1/2, miR-302c-5p, miR-3664-5p, miR-3714, miR-513a-3p, miR-590-3p/5p, miR-130b, miR-186, and miR-133a/b. These miRNAs bound to the 3′-untranslated regions of GST mRNA and inhibited GST expression, thus blocking GSH consumption and resulting in accumulation of intracellular GSH48–51. It is worth mentioning that miR-133a/b served as effective suppressors of GST in different cancer types, such as bladder cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer and head and neck carcinoma. Inhibition of miR-133a/b reversed both increased GSH and insensitivity to drugs51–54. Furthermore, GPX family members are targeted by miRNAs and results in defect of ROS neutralization. In one report, GPX4 was decreased by miR-181a-5p in osteoarthritis55. However, the relationship between GPX4 and miRNAs in cancer is still in dark. Only GPX2 and GPX3 have been found to be modulated by miRNAs such as miR-17, miR-17-3p, miR-196a, and miR-921 in colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, and lung cancer56–59. Overall, regulation of GSH by miRNAs occurs mainly through control of GST and GPX family members. Since GSH has been shown to participate in growth of tumors and chemoresistance to drugs which induce intracellular oxidative stress, miRNAs may regulate ferroptosis and control cancer progression via modulation of GSH.

Table 1.

Summary of GSH associated miRNAs in cancer.

| Name | Associated cancer type | Target | Influence to GSH | Model of evidence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-27a | Bladder cancer, colorectal cancer | SLC7A11, ZBTB10 | Up/Down | Cell culture, animal models | 42,43 |

| miR-143 | Colorectal cancer | GPX | Up | Animal models | 199 |

| miR-17 | Prostate cancer | GPX2 | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 56 |

| miR-17-3p | Prostate cancer | GPX2 | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 57 |

| miR-196a | Lung cancer | GPX3 | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 58 |

| miR-921 | Lung cancer | GPX3 | Up | Cell culture | 59 |

| miR-124 | Colorectal cancer | GST | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 48 |

| Let-7a-5p | Prostate cancer | GST | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 49 |

| miR-92b-3p | Prostate cancer | GST | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 49 |

| miR-129-5P | Colorectal cancer cells | GST | Up | Cell culture | 50 |

| miR-144 | Prostate cancer | GST | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 51 |

| miR-153-1/2 | Prostate cancer | GST | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 51 |

| miR-302c-5p | Colorectal cancer | GST | Up | Cell culture | 50 |

| miR-3664-5p | Colorectal cancer | GST | Up | Cell culture | 50 |

| miR-3714 | Colorectal cancer | GST | Up | Cell culture | 50 |

| miR-513a-3p | Colorectal cancer, lung cancer | GST | Up | Cell culture | 200 |

| miR-590-3p/5p | Prostate cancer | GST | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 51 |

| miR-133a/b | Bladder cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | GST | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 52,53,201 |

| miR-130b | Ovarian cancer | GST | Up | Cell culture | 202 |

| miR-186 | Ovarian cancer | GST | Up | Cell culture | 203 |

| miR-34b | Prostate cancer | MYC | Up | Cell culture | 204 |

| miR-K12-11 | Kaposi’s sarcoma | xCT | Up | Cell culture | 205 |

| miR-18a | Hepatocellular carcinoma | GCL | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 37 |

| miR-218 | Bladder cancer | GCL | Down | Cell culture | 38 |

| miR-21 | Lung cancer | GSH | Down | Cell culture | 44 |

| miR-24-2 | Colorectal cancer | GSH | Down | Clinical samples | 45 |

| miR-497 | Cervical cancer | GSH | Down | Cell culture | 46 |

| miR-503 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | GSH | Down | Cell culture | 47 |

| miR-152 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | GST | Down | Cell culture | 39 |

| miR-155 | Lung cancer | GST | Down | Cell culture | 40 |

| miR-326 | Glioma | PKM2 | Down | Cell culture | 41 |

| miR-125b | Chronic lymphocytic leukemias | GSH | Unknown | Cell culture | 206 |

Fig. 1. Regulation of ncRNAs to ferroptosis.

a Regulation of ncRNAs to GSH metabolism; b Regulation of ncRNAs to iron metabolism; c Regulation of ncRNAs to KEAP1-NRF2 pathway.

MiRNAs and iron

Iron metabolism is another key factor in ferroptosis. Excessive iron increases ROS via Fenton reaction and ROS is neutralized by iron reversely60. Metabolism of iron mainly includes interaction between transferrin (TF) and its receptor (TFR), import of iron via divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1), storage of iron as ferritin and iron-sulfur cluster (ISC), and export of iron via ferroportin (FPN)61,62. The specific realtion between miRNAs and iron is summarized in Table 2, and the schematic diagram of these interactions are shown in Fig. 1b. In colorectal cancer, targeting of DMT1 by miR-149 and miR-19a led to decreased iron import63. Furthermore, in colorectal cancer and hepatocellular cancer, TFR was targeted by miRNAs including miR-141, miR-145, miR-152, miR-182, miR-200a, miR-22, miR-31, miR-320, miR-758, and miR-19463–65. This inhibition led to disruption of interaction between TF and TFR and the following decreased iron import. Thereinto, miR-194 suppressed the expression of both TFR and FPN in colorectal cancer63. FPN was also targeted by miR-150, miR-17-5p, miR-20a, and miR-492 in hepatocellular carcinoma, multiple myeloma, lung cancer, and prostate cancer, respectively66–68. Furthermore, ferritin which is composed of ferritin heavy chain (FHC) and ferritin light chain (FLC), is controlled by miRNAs69. FHC could be targeted by miR-200b, miR-181a-5p, miR-19b-1-5p, miR-19b-3p, miR-210-3p, miR-362-5p, miR-616-3p, and miR-638 in prostate cancer, resulting in decreased intracellular iron65,70,71. FLC could be targeted by miR-133a in colorectal cancer and breast cancer, and knockdown of miR-133a restored the reduced iron levels inside cancer cells63,72. Among the miRNAs that regulate iron levels, miR-210 serves as an important member. In colorectal cancer cells, miR-210 was activated by hypoxia and then targeted ISCU to alter intracellular iron homeostasis73. Furthermore, transfection of miR-210 decreased the uptake of iron via TFR suppression74. On the contrary, miRNAs can be modulated by iron. MiR-107, miR-125b, and miR-30d were inhibited by iron in hepatocellular carcinoma and ovarian cancer75,76, and miR-146a, miR-150, miR-214-3p and miR-584 were increased by iron in ovarian cancer and neuroblastoma76,77. This phenomenon may derive from the induction of excess ROS by iron and the subsequent regulation of miRNAs transcription. Overall, different miRNAs regulate iron levels in various directions, and the imbalance of iron leads to run-away miRNA expression.

Table 2.

Summary of iron associated miRNAs in cancer.

| Name | Associated cancer type | Target | Influence to iron | Model of evidence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-150 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | FPN | Up | Cell culture | 76 |

| miR-17-5p | Multiple myeloma | FPN | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 66 |

| miR-20a | Lung cancer | FPN | Up | Cell culture | 67 |

| miR-492 | Prostate cancer | FPN | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 68 |

| miR-194 | Colorectal cancer | TFR1, FPN1 | Up | Clinical samples | 63 |

| miR-449a | Glioma | CDGSH iron sulfur domain 2 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 207 |

| miR-149 | Colorectal cancer | DMT1 | Down | Clinical samples | 63 |

| miR-19a | Colorectal cancer | DMT1 | Down | Clinical samples | 63 |

| miR-181a-5p | Prostate cancer | FHC | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 70 |

| miR-19b-1-5p | Prostate cancer | FHC | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 70 |

| miR-19b-3p | Prostate cancer | FHC | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 70 |

| miR-210-3p | Prostate cancer | FHC | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 70 |

| miR-362-5p | Prostate cancer | FHC | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 70 |

| miR-616-3p | Prostate cancer | FHC | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 70 |

| miR-638 | Prostate cancer | FHC | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 70 |

| miR-200b | Hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer | Ferritin | Down | Cell culture | 65,71 |

| miR-133a | Colorectal cancer, breast cancer | FLC | Down | Cell culture | 63,72 |

| miR-29 | Lung cancer | Iron-responsive element binding protein 2 | Down | Clinical samples | 208 |

| miR-210 | Renal cancer, head and neck paragangliomas, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas | ISCU, TFR1 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 73,74,209–211 |

| miR-126 | Malignant mesothelioma | Mitochondria-destabilizing stress signals | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 212 |

| miR-7-5p | Ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer | Mitoferrin | Down | Cell culture | 30 |

| miR-122 | Hepatocellular cancer | Nocturnin | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 213 |

| miR-34a | Lung cancer | P53 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 214 |

| miR-141 | Colorectal cancer | TFR1 | Down | Clinical samples | 63 |

| miR-145 | Colorectal cancer | TFR1 | Down | Clinical samples | 63 |

| miR-152 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | TFR1 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 64 |

| miR-182 | Colorectal cancer | TFR1 | Down | Clinical samples | 63 |

| miR-200a | Hepatocellular carcinoma | TFR1 | Down | Cell culture | 65 |

| miR-22 | Hepatocellular cancer | TFR1 | Down | Cell culture | 65 |

| miR-31 | Colorectal cancer | TFR1 | Down | Clinical samples | 63 |

| miR-320 | Hepatocellular cancer | TFR1 | Down | Cell culture | 65 |

| miR-758 | Colorectal cancer | TFR1 | Down | Clinical samples | 63 |

| miR-107 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | – | Inhibited by iron | Cell culture, animal models | 75 |

| miR-125b | Ovarian cancer | – | Inhibited by iron | Cell culture | 76 |

| miR-30d | Hepatocellular carcinoma | – | Inhibited by iron | Cell culture, animal models | 75 |

| miR-146a | Ovarian cancer | – | Induced by iron | Cell culture | 76 |

| miR-150 | Ovarian cancer | – | Induced by iron | Cell culture | 76 |

| miR-214-3p | Neuroblastoma | – | Induced by iron | Cell culture | 77 |

| miR-584 | Neuroblastoma | – | Induced by iron | Cell culture | 77 |

MiRNAs and NRF2

NRF2 serves as a transcriptional factor and activates downstream antioxidant factors. The expression of NRF2 mainly depends on Kelch-like ECh-Associated Protein 1 (KEAP1), which assembles Cullin3 to form the Cullin-E3 ligase complex and then degrades NRF2 protein via the ubiquitin-proteasome route78. Inhibition of NRF2 has been confirmed to enhance ferroptosis79. The specific information regarding interaction between miRNAs and NRF2 is listed in Table 3, and the schematic diagram is shown in Fig. 1c. In esophageal cancer, miR-129, miR-142, miR-144-3p, miR-450, miR-507, and miR-634 targeted the 3′-untranslated region of NRF2 mRNA and decreased NRF2 expression, resulting in an increase of ROS80–85. Among these miRNAs, miR-144-3p played an important role in the regulation of NRF2. Targeting NRF2 by miR-144-3p inhibited tumor progression in melanoma and acute myeloid leukemia86, and increased the sensitivity of lung cancer cells to cisplatin87, indicating the role of miR‑144‑3p in oxidative homeostasis. Other miRNAs that targeted NRF2 include miR-144, miR-153, miR-200c, and miR-212-3p, although their effects have not been explored82,88–90. Moreover, miRNAs regulate NRF2 via targeting KEAP1. In hepatocellular carcinoma, ovarian cancer, leukemia, and neuroblastoma cells, KEAP1 was targeted by miR-141, miR-23a, miR-432, miR-7, and miR-200a88,91–95. Thereinto, miR-200a served as an active role. In esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, methylseleninic acid activated KEAP1/NRF2 pathway via upregulating miR-200a, the latter inhibited KEAP1 expression and induced expression of NRF296. In breast cancer and pancreatic adenocarcinoma, miR-200a suppression reverted expression of KEAP1 and then inhibited NRF2 and promoted the anchorage-independent cell growth in vitro97. In turn, NRF2 enhances miRNAs expression via binding to the antioxidative response element box. In myelocytic leukemia, miR-125b driven by NRF2 promoted leukemic cells survival. Inhibition of miR-125b enhanced responsiveness of leukemic cells towards chemotherapy98. However, in oral squamous cell carcinoma, repression of miR-125b by peroxiredoxin like 2A (PRXL2A) protected cancer cells from drug-induced oxidative stress in an NRF2-depedent manner99, indicating the mutual regulation between miR-125b and NRF2. In addition, expression of miR-29B1, miR-129-3p, and miR-380-3p was induced by NRF2 in acute myelocytic leukemia, hepatocellular carcinoma, and neuroblastoma98,100,101. Conversely, miR-181c, miR-378, miR-122, miR-17-5p, miR-1, and miR-206 were repressed by NRF2 in various cancer types66,102–107. Thereinto, inhibition of miR-1 and miR-206 was mediated by SOD1 induced by NRF2 but not the role of NRF2 as a transcriptional factor. In summary, miRNAs regulate NRF2 pathway through targeting KEAP1 and NRF2 mRNAs. Conversely, NRF2 controls miRNAs via transcription or downstream factor SOD1.

Table 3.

Summary of NRF2 associated miRNAs in cancer.

| Name | Associated cancer type | Target | Influence to NRF2 | Model of evidence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-141 | Hepatocellular carcinoma, ovarian cancer | KEAP1 | Up | Cell culture | 88,91–93 |

| miR-23a | Leukemic | KEAP1 | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 94 |

| miR-432 | Esophageal cancer | KEAP1 | Up | Cell culture | 92,95 |

| miR-7 | Neuroblastoma cells | KEAP1 | Up | Cell culture | 92 |

| miR-200a | Breast cancer, esophageal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and pancreatic adenocarcinomas | KEAP1, | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 81,92,96,97,215,216 |

| miR-155 | Lung cancer | NRF2 | Up | Cell culture | 217 |

| miR-101 | Hepatocellular carcinoma, prostate cancer | NRF2, SOD1 | Up/Down | Cell culture, animal models | 88,105,218 |

| miR-1 | Lung cancer, prostate cancer | NRF2, SOD1 | Up/Inhibited by NRF2 | Cell culture, animal models | 105,107 |

| miR-206 | Lung cancer, prostate cancer | NRF2, SOD1 | Up/Inhibited by NRF2 | Cell culture, animal models | 105–107 |

| miR-148b | Endometrial cancer | ERMP1 | Down | Cell culture | 219 |

| miR-129 | Esophageal cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 80 |

| miR-129-5a | Esophageal cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 80,81 |

| miR-129-5p | Esophageal cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 80 |

| miR-142 | Esophageal cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture | 82 |

| miR-144 | Hepatocellular carcinoma, leukemia, hepatocellular carcinoma, neuroblastoma | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture | 88,89 |

| miR-144-3p | Melanoma, lung cancer, and acute myeloid leukemia | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture | 86,87,220,221 |

| miR-153 | Neuroblastoma, breast cancer, and oral squamous cell carcinoma | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture | 82,90 |

| miR-200c | Lung cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 222 |

| miR-212-3p | Melanoma | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture | 86 |

| miR-23b-3p | Melanoma | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture | 86 |

| miR-27 | Neuroblastoma | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 223 |

| miR-28 | Breast cancer, esophageal cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture | 81,224 |

| miR-340 | Hepatocellular carcinoma, esophageal cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture | 85,88,92 |

| miR-34a | Breast cancer, colon cancer, ovarian cancer, and lung cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture | 225,226 |

| miR-450 | Esophageal cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture | 83 |

| miR-450a | Esophageal cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 80,81 |

| miR-495 | Nonsmall-cell lung cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture | 227 |

| miR-507 | Esophageal cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 80,81,84 |

| miR-634 | Esophageal cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 80,81,85 |

| miR-93 | Pancreatic adenocarcinomas, breast cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 97,221 |

| miR-93-5p | Melanoma | NRF2 | Down | Clinical samples | 86 |

| miR-125b | Acute myelocytic leukemia, oral squamous cell carcinoma, and renal cancer | NRF2 | Down/Induced by NRF2 | Cell culture, animal models | 98,99,228 |

| miR-181c | Colorectal cancer | – | Inhibited by NRF2 | Cell culture, animal models | 102 |

| miR-378 | Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | – | Inhibited by NRF2 | Cell culture, animal models | 103 |

| miR-122 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | – | Inhibited by NRF2 | Cell culture | 104 |

| miR-17-5p | Multiple myeloma | – | Inhibited by NRF2 | Cell culture, animal models | 66 |

| miR-29B1 | Acute myelocytic leukemia | – | Induced by NRF2 | Cell culture | 98 |

| miR-129-3p | Hepatocellular carcinoma | – | Induced by NRF2 | Cell culture, animal models | 100 |

| miR-380-3p | Neuroblastoma | – | Induced by NRF2 | Cell culture, animal models | 101 |

MiRNAs and ROS

In addition to factors above, miRNAs regulate ROS via other mechanisms. The information of miRNAs that are related to ROS in cancer is listed in Table 4. MiRNAs can positively regulate ROS levels. For example, miR-21 whose expression increased with tumor grade, has been identified to enhance ROS level in lung cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, ovarian cancer, and prostate cancer108–113. Mechanically, miR-21 targeted STAT3, proline oxidase (POX), and programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) to induce oxidative stress114–116. Moreover, miR-146a has attracted much attention. In ovarian cancer, miR-146a repressed SOD2 expression and inhibited proliferation of cancer cells and enhanced chemosensitivity to drugs117. In lung cancer, suppression of miR-146a restored catalase and inhibited ROS induction, and protected cancer cells from cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity118. In addition, overexpression of miR-124, miR-526b, and miR-655 led to excess ROS via thioredoxin reductase 1 in breast cancer119,120. Furthermore, the antioxidant enzyme SOD1 was downregulated by stable expression of miR-143 or miR-145 in colorectal cancer121. This indicates that miRNAs enhance intracellular ROS via different manners. On the other hand, in lung cancer, miR-99 suppressed the invasion and migration of cancer cells via targeting NOX4-mediated ROS production122. Additionally, miR-520 and miR-373 reduced ROS via targeting NF-κB and TGF-β signaling pathways and repressed growth and lymph node metastasis of breast cancer123. Other miRNAs such as let-7, miR-137, miR-193b, miR‑199, and miR-26a, have been found to decrease ROS level in cancer cells via diverse targets such as heme oxygenase-1, C-MYC, and triglyceride124–128, indicating that miRNAs inhibit ROS level. Conversely, miR-133a, miR-150-3p, miR-1915-3p, miR-206, miR-34, miR-638, and miR-182 were activated by oxidative stress and then played a role in the subsequent biological processes129–133. Moreover, miR-125, miR-145-5p, miR-17-5p, miR-199, and miR-17-92, were decreased by excess intracellular ROS134–137. Among them, miR-125b plays a dual role in oxidative homeostasis. As discussed above, miR-125b serves as a regulator of NRF2. In addition, miR-125b could be inhibited by ROS via a DNMT1-dependent DNA methylation in ovarian cancer140. Moreover, although miR-21 has been discussed as the enhancer of ROS in breast cancer, DNA damage induced by ROS led to activation of miR-21 via NF-κB, indicating the interaction between miRNAs and ROS138. In total, we can infer that altered levels of GSH, iron, and NRF2 are not the only methods by which miRNAs regulate ROS and vice versa in, miRNAs and ROS can also regulate each other in various pathways.

Table 4.

Summary of ROS associated miRNAs in cancer.

| Name | Associated cancer type | Target | Influence to ROS | Model of evidence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-124 | Non-small cell lung cancer | TXNRD1 | Up | Cell culture | 120 |

| miR-125a | Osteosarcoma | Estrogen-related receptor alpha | Up | Cell culture | 229 |

| miR-128a | Medulloblastoma | BMI-1 | Up | Cell culture | 230 |

| miR-139-5p | Breast cancer | Unknown | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 231 |

| miR-143 | Colorectal cancer | SOD1 | Up | Cell culture | 121 |

| miR-146a | Lung cancer, ovarian Cancer | Catalase, SOD2 | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 117,118 |

| miR-146b-5p | Leukemic | Unknown | Up | Cell culture | 232 |

| miR-15 | Colorectal cancer, cancer stem cells | C-MYC | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 233 |

| miR-155 | Glioma, pancreatic cancer | MAPK13, MAPK14, and Foxo3a | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 234,235 |

| miR-15a-3p | Lung cancer | P53 | Up | Cell culture | 236 |

| miR-16 | Colorectal cancer, cancer stem cells | C-MYC | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 233 |

| miR-186 | Colorectal cancer | CKII | Up | Cell culture | 237 |

| miR-193a-3p | Glioma | γH2AX | Up | Cell culture | 238 |

| miR-210 | Cancer stem cells, glioma | P53 | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 239 |

| miR-212 | Colorectal cancer | MnSOD | Up | Clinical samples | 240 |

| miR-216b | Colorectal cancer | CKII | Up | Cell culture | 237 |

| miR-22 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | SIRT-1 | Up | Cell culture | 241 |

| miR-223 | Breast cancer | HAX-1 | Up | Cell culture | 242 |

| miR-23b-3p | Acute myeloid leukemia | PrxIII | Up | Cell culture | 243 |

| miR-25-5p | Colorectal cancer | SOX10 | Up | Cell culture | 244 |

| miR-26a-5p | Acute myeloid leukemia | PrxIII | Up | Cell culture | 243 |

| miR-26b | Small cell lung cancer | Myeloid cell leukemia 1 protein | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 245 |

| miR-30 | Gastric cancer | P53 | Up | Cell culture | 246 |

| miR-337-3p | Colorectal cancer | CKII | Up | Cell culture | 237 |

| miR-34c | Nonsmall cell lung cancer | HMGB1 | Up | Cell culture | 247 |

| miR-371-3p | Lung cancer | PRDX6 | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 248 |

| miR-422a | Gastric cancer | PDK2 | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 249 |

| miR-4485 | Breast cancer | Mitochondrial protein | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 133 |

| miR-4673 | Lung cancer | 8-Oxoguanine-DNA Glycosylase-1 | Up | Cell culture | 250 |

| miR-504 | Lung cancer | P53 | Up | Cell culture | 251 |

| miR-506 | Lung cancer | P53, NF-κB | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 252 |

| miR-509 | Breast cancer | P53 | Up | Cell culture | 253 |

| miR-526b | Breast cancer | Thioredoxin Reductase 1 | Up | Cell culture | 119 |

| miR-551b | Lung cancer | MUC1 | Up | Cell culture | 254 |

| miR-655 | Breast cancer | Thioredoxin Reductase 1 | Up | Cell culture | 119 |

| miR-661 | Colorectal cancer | Hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, pyruvate kinase M2 | Up | Cell culture | 255 |

| miR-760 | Colorectal cancer | CKII | Up | Cell culture | 237 |

| miR-92 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Unknown | Up | Clinical samples | 256 |

| miR-128 | Glioma, hepatocellular carcinoma | PKM2 | Up/Down | Cell culture | 257 |

| miR-145 | Colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma | SOD1, PKM2 | Up/Down | Cell culture | 121,258 |

| miR-211 | Myeloma, oral carcinoma | PRKAA1, TCF12 | Up/Down | Cell culture, animal models | 259,260 |

| miR-222 | Hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer | NF-κB, TGF-β | Up/Down | Cell culture, animal models | 261,262 |

| miR-23a/b | Myeloma, renal cancer | C-MYC, POX | Up/Down | Cell culture, animal models | 263,264 |

| miR-29 | Ovarian cancer, lung cancer, and lymphoma | C-MYC, SIRT1 | Up/Down | Cell culture, animal models | 265,266 |

| miR-34a | Gastric cancer, glioma | NOX2 | Up/Down | Cell culture | 267 |

| Let-7 | Hepatocellular carcinoma, prostate cancer, and pancreatic cancer | Heme oxygenase-1, P53 | Up/Down | Cell culture, animal models | 123,268 |

| miR-33a | Glioma, hepatocellular carcinoma | SIRT6 | Up/Down | Cell culture, animal models | 269 |

| miR-221 | Hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer | NF-κB, TGF-β, and DICER | Up/Down/Induced by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 261,262,270 |

| miR-21 | Lung cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, ovarian cancer, and prostate cancer | SOD, MAPK, SOD2, Glucose, NFκB, STAT3, POX, and PDCD4 | Up/Down/Induced by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 108,112,114,271 |

| miR-17-92 | Gastric cancer, lung cancer | C-MYC, P53, and NFκB | Up/Down/Inhibited by ROS | Cell culture | 137,272,273 |

| miR-181 | Hepatocellular carcinoma, uterine leiomyoma | Unknown | Up/Induced by ROS | Cell culture | 132,274 |

| miR-200 | Breast cancer, cancer stem cells, hepatocellular carcinoma, and lung cancer | P53, PRDX2, GAPB/NRF2, SESN1 | Up/Induced by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 222,275–277 |

| miR-34 | Cancer stem cells, bladder cancer, lung cancer | C-MYC, P53 | Up/Induced by ROS | Cell culture | 278,279 |

| miR-182 | Uterine leiomyoma, lung cancer | PDK4 | Up/Induced by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 132,133 |

| miR-199 | Gastric cancer, ovarian cancer | DNMT1 | Up/Inhibited by ROS | Cell culture | 134 |

| miR-20a | Breast cancer, pancreatic cancer | BECN1, ATG16L1, and SQSTM1 | Up/Inhibited by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 136,280 |

| miR-125b | Hepatocellular carcinoma, ovarian cancer, and breast cancer | Hexokinase 2, DNMT1, and HAX-1 | Up/Inhibited by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 228,281 |

| miR-1246 | Breast cancer | NF-κB, TGF-β | Down | Cell culture | 124 |

| miR-137 | Ovarian cancer | C-MYC | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 125 |

| miR-193b | Liposarcoma | Antioxidant methionine sulfoxide reductase A | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 127 |

| miR-199a-3p | Testicular cancer | Transcription factor specificity protein 1 | Down | Cell culture | 126 |

| miR-26a | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Triglyceride, totalcholesterol, malondialdehyde | Down | Cell culture | 128 |

| miR-30c-2-3p | Breast cancer | NF-κB, TGF-β | Down | Cell culture | 282 |

| miR-346 | Ovarian cancer | GSK3B | Down | Cell culture | 283 |

| miR-373 | Breast cancer | NF-κB, TGF-β | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 123 |

| miR-520 | Breast cancer | NF-κB, TGF-β | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 123 |

| miR-7 | Nonsmall cell lung cancer | MAFG | Down | Cell culture | 284 |

| miR-885-5p | Hepatocellular carcinoma | TIGAR | Down | Cell culture | 285 |

| miR-99a | Lung cancer | NOX4 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 122 |

| miR-133a | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 9 | Induced by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 129 |

| miR-150-3p | Hepatocellular carcinoma | – | Induced by ROS | Cell culture | 130 |

| miR-1915-3p | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | – | Induced by ROS | Cell culture | 130 |

| miR-206 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | – | Induced by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 131 |

| miR-34a-3p | Hepatocellular carcinoma | – | Induced by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 129 |

| miR-34a-5p | Hepatocellular carcinoma | – | Induced by ROS | Cell culture | 130 |

| miR-638 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | – | Induced by ROS | Cell culture | 130 |

| miR-125 | Gastric cancer | – | Inhibited by ROS | Cell culture | 134 |

| miR-145-5p | Gastric cancer | – | Inhibited by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 135 |

| miR-17-5p | Pancreatic cancer | – | Inhibited by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 136 |

| miR-27a | Pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer | – | Inhibited by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 286 |

| miR-328 | Gastric cancer | – | Inhibited by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 287 |

| miR-329 | Breast cancer | – | Inhibited by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 288 |

| miR-362-3p | Breast cancer | – | Inhibited by ROS | Cell culture, animal models | 288 |

LncRNAs and ferroptosis

LncRNAs mainly serve as regulators of transcription factors in nucleus or as sponges of miRNAs in cytoplasm139. Linc00336 was promoted by lymphoid-specific helicase in lung cancer and inhibited ferroptosis via sponging miR-685232. Furthermore, in breast cancer and lung cancer, lncRNA P53rra bound to Ras GTPase-activating protein-(SH3domain)-Binding Protein 1 (G3BP1) and displaced P53 from a G3BP1 complex, resulting in retention of P53 in nucleus and downregulation of SLC7A11140. In addition, ferroptosis inducer erastin upregulated lncRNA GA binding protein transcription factor subunit beta 1 (GABPB1) antisense RNA 1 (Gabpb1-AS1), which suppressed GABPB1 and led to downregulation of peroxiredoxin-5 peroxidase and suppression of cellular antioxidant capacity in hepatocellular carcinoma141. Interaction between lncRNAs and ferroptosis has been listed (Supplementary Table 1), and the relationship between lncRNAs and ferroptosis associated factors is summarized in Table 5. The schematic diagram of these interactions is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 5.

Summary of GSH, iron, NRF2, and ROS associated lncRNAs in cancer.

| Control point | Name | Associated cancer type | Target | Influence to control point | Model of evidence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSH | Linc01419 | Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | GST | Up | Clinical samples | 144 |

| Neat1 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | GST | Up | Cell culture | 143 | |

| H19 | Ovarian cancer | GCLC, GCLM, GST | Up/Down | Cell culture, animal models | 145 | |

| Xist | Colorectal cancer | GST | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 48 | |

| Ror | Breast cancer | GST | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 142 | |

| Iron | Pvt1 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | miR-150/HIG2 | Up | Cell culture, animal models | 146 |

| H19 | Myeloid leukemia | miR-675 | Inhibited by iron | Cell culture | 147 | |

| NRF2 | Aatbc | Bladder cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 148 |

| Kral | Hepatocellular carcinoma | KEAP1 | Down | Cell culture | 91 | |

| Malat1 | Multiple myeloma | KEAP1 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 149 | |

| H19 | Ovarian cancer | NRF2 | Down | Cell culture, animal models | 145 | |

| Scal1 | Lung cancer | – | Induced by NRF2 | Cell culture | 92 | |

| Loc344887 | Gallbladder cancer | – | Induced by NRF2 | Cell culture | 150 | |

| ROS | Meg3 | Lung cancer | P53 | Up | Cell culture | 154 |

| Uca1 | Bladder cancer | miR-16 | Down | Cell culture | 151 | |

| Gas5 | Melanoma | G6PD | Down | Cell culture | 153 | |

| H19 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | MAPK/ERK signaling pathway | Down | Cell culture | 152 | |

| Miat | Neuroblastoma, glioblastoma | MAPK7, FUT8, and MCL1 | Unknown | Cell culture | 289–295 |

LncRNAs and ferroptosis associated factors

Since there are only a few studies about lncRNAs and ferroptosis factors, we will discuss them together. Regulation of GSH by lncRNAs in cancer mainly depends on GST and GCL46. In breast cancer, knockdown of lncRNA Ror led to reduced multidrug resistance-associated P-glycoprotein and GST expression, resulting in restored sensitivity of breast cancer cells to tamoxifen142. Similarly, in colorectal cancer, knockdown of lncRNA Xist inhibited doxorubicin resistance via suppressing GST and increasing GSH48. Furthermore, in hepatocellular carcinoma cells, silencing lncRNA Neat1 inhibited IL-6-induced STAT3 phosphorylation which contributed to the increase of GST143. In addition, lncRNA Linc01419 bound to the promoter region of GSTP1 and recruited DNA methyltransferase, increasing promoter methylation and decreasing GST expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma144. Moreover, knockdown of lncRNA H19 resulted in recovery of cisplatin sensitivity via reduction of GCL and GST145. In total, regulation of GSH by lncRNAs mainly depends on GST and GCL. Moreover, in hepatocellular carcinoma, silencing of lncRNA Pvt1 inhibited TFR expression and obstructed iron uptake via miR-150146. Furthermore, silencing of FHC in leukemia cells induced production of ROS and altered downstream genes via increasing H19 and miR-657 expression147. This means that lncRNAs are associated with iron metabolism in cancer cells. Moreover, in bladder cancer, suppression of NRF2 by lncRNA associated transcript in bladder cancer (Aatbc) resulted in apoptosis148. In multiple myeloma, metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (Malat1) which has been proved to play a role in various cancers, inhibited NRF2 via activation of their negative regulator KEAP1149. Furthermore, overexpression of Keap1 regulation-associated lncRNA (Kral) inhibited NRF2 via increasing KEAP1 expression, and reversed the resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells to 5-fluorouracil91. Therefore, lncRNAs regulate NRF2 expression via direct and indirect manners. On the contrary, NRF2 participates in regulation of lncRNAs. In gallbladder cancer, downregulation of lncRNA loc344887 suppressed cell proliferation and decreased migration and invasion. Further studies found that loc344887 was upregulated after ectopic expression of NRF2150. In a recent study, NRF2 activated smoke and cancer-associated lncRNA 1 (Scal1) and induced oxidative stress protection. Knockdown of NRF2 suppressed Scal1 and alleviated the proliferation of lung cancer cells92. In sum, lncRNAs can regulate NRF2 by directly controlling expression or modulating KEAP1 indirectly, and NRF2 can regulate lncRNAs expression reversely.

Other than the factors above, lncRNAs regulate ROS levels via various mechanisms. In bladder cancer, lncRNA urothelial cancer associated 1 (Uca1) decreased ROS level via targeting miR-16 which led to decreased GSH synthetase151. Furthermore, in hepatocellular carcinoma, downregulation of H19 increased ROS via MAPK/ERK signaling pathway and reversed chemotherapy resistance152. Moreover, knockdown of lncRNA growth arrest specific 5 (Gas5) in melanoma enhanced intracellular ROS via increased superoxide anion and NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4)-oxidized GSH153. In lung cancer cells, the intracellular oxidative stress induced by paclitaxel was attenuated by knockdown of maternally expressed 3 (Meg3), and Meg3 overexpression induced cell death and increased sensitivity to paclitaxel in an ROS-dependent manner154. In total, lncRNAs influence ROS metabolism via control of GSH, iron, NRF2 and other factors, and these factors can regulate lncRNAs expression reversely.

Other ncRNAs and ferroptosis

CircRNAs, tRNAs, rRNAs, piRNAs, snRNAs, and snoRNAs are also contained in family of noncoding RNAs21. However, studies on the relations between these ncRNAs and ferroptosis are few. The interactions have been listed (Supplementary Table 2). The schematic diagram of these interactions is shown in Fig. 1.

CircRNAs

CircRNAs are covalently closed, single-stranded RNA molecules derive from exons via alternative mRNA splicing22. Several studies have uncovered function of circRNAs in ferroptosis. In glioma, circ-TTBK2 enhanced cell proliferation and invasion and inhibited ferroptosis via sponging miR-761 and subsequent ITGB8 activation, knockdown of circ-TTBK2 promoted erastin-induced ferroptosis155. Furthermore, circ0008035 inhibited ferroptosis in gastric cancer via miR-599/EIF4A1 axis. Knockdown of circ0008035 enhanced anticancer effect of erastin and RSL3 via increased iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation156. According to ferroptosis associated factors, in gastric cancer, circPVT1 promoted multidrug resistance by enhancing P-gp and GSTP. MRNA levels of P-gp and GSTP were obviously repressed after downregulation of circ-PVT1 in paclitaxel-resistant gastric cancer cells157. Moreover, high-throughout microarray-based circRNA profiling revealed that 526 circRNAs were dysregulated in cervical cancer cells, and bioinformatic analyses indicated that these circRNAs participated mainly in GSH metabolism158. However, associated miRNAs and downstream factors were not screened. Thus, further studies on the modulation of ferroptosis by circRNAs are needed.

TRNAs

TRNAs serve as adapter molecules between mRNAs and proteins. The interaction between tRNAs and ferroptosis includes two possible manners. First, tRNAs are required in the synthesis of ferroptosis associated factors such as SLC7A11, GPX4, and IREB2, thus the mutation of tRNAs may alter the expression of these factors and then influence ferroptosis217. Second, tRNAs have multiple interaction partners including aminoacyl-tRNA-synthetases, mRNAs, ribosomes and translation factors159. Among them, cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase plays a role in ferroptosis. In fibrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma and pancreatic carcinoma, loss of cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase suppressed erastin-induced ferroptosis via increasing intracellular GSH and transsulfuration, and inhibition of the transsulfuration pathway resensitized cells to erastin160. Interestingly, tRNAs mutation may control ferroptosis in an opposite manner. Selenocysteine which is formed from serine at the respective tRNA, is a component of GPXs. However, in hepatoma, colorectal cancer and breast cancer, the mutation of tRNA led to decline of selenoprotein expression except GPX4 and GPX1, and weak ferroptosis alteration161–163. This indicates that tRNAs modulate GSH levels mainly via synthesis but not metabolism. In addition, tRNAs influence ROS levels via various manners. Lung cancer mouse model with deletion of selenocysteine-tRNA gene exhibited ROS accumulation and increased susceptibility to lymph nodules metastasis164. Additionally, Queuine-modified tRNAs promoted cellular antioxidant defense via catalase, SOD, GPX, and GSH reductase and inhibited lymphoma165. In total, tRNAs decrease GSH synthesis and increase ferroptosis without modulating GPX4, while on the other hand, tRNAs enhance the antioxidant defense system and then inhibit ferroptosis.

RRNAs

RRNAs constitute the structural and functional core of ribosomes166. Some reports have provided clues for role of rRNAs in ferroptosis. In cervical cancer, NRF2 was found to contain a highly conserved 18S rRNA binding site on 5′ untranslated region that is required for internal initiation. Deletion of this site remarkably enhanced translation, indicating that the 18S rRNA regulates NRF2 expression167. In another study, hepatoma cells treated with ethidium bromide exhibited a 70% decrease in the 16S/18S rRNA ratio and enhanced NRF2 expression168. However, whether NRF2 and 18S rRNA are mutually regulated remains unclear. Regarding ROS, nuclear mitotic apparatus protein (NuMA) is involved in cellular events such as DNA damage response, apoptosis, and P53-mediated growth arrest. In breast cancer cells, NuMA bound to 18S and 28S rRNAs and localized to rDNA promoter regions. Downregulation of NuMA expression triggered nucleolar oxidative stress and decreased pre-rRNA synthesis169. Furthermore, in leukemia HL-60 cells treated with iron chelator deferoxamine, rRNA synthesis in nucleoli was inhibited170. In conclusion, interaction between rRNAs and ferroptosis has not been completely uncovered. Role of ribosomes as the place in which proteins related to ferroptosis are synthesized may provide clues for further studies.

PiRNAs, snRNAs, and snoRNAs

PiRNAs are the class of small ncRNA molecules distinct from miRNAs in that they are larger, lack sequence conservation, and are more complex171. PiRNAs are involved in tumorigenesis of variety cancers172. However, studies on piRNAs and ferroptosis are few. In prostate cancer, piR-31470 formed a complex with piwi-like RNA-mediated gene silencing 4 (PIWIL4). This complex recruited DNMT1, DNA methyltransferase 3 alpha, and methyl-CpG binding domain protein 2 to initiate and maintain the hypermethylation and inactivation of GSTP1. Overexpression of piR-31470 inhibited GSTP1 expression and increased vulnerability to oxidative stress and DNA damage in human prostate epithelial RWPE1 cells, resulting in tumorigenesis173. However, the GSTP1 inactivation may inhibit tumor growth via induction of ferroptosis once the tumors are formed. Clearly, further studies are needed to explore the roles of piRNAs in different stages of cancer. SnoRNAs are a class of small RNA molecules that mediate modifications of rRNAs, tRNAs, and snRNAs. The snoRNA ACA11 was overexpressed in multiple myeloma cells, increasing ROS and resulting in protein production and cell proliferation174. There are currently no reports on ferroptosis and snRNAs which mediate post-transcriptional splicing in gene expression. In cervical cancer and osteosarcoma, assembly chaperones and core proteins devoted to snRNA maturation contributed to recruiting trimethylguanosine synthase 1 to selenoprotein mRNAs including GPX1 for cap hypermethylation175. Future studies should focus on the possible regulation of snRNAs towards GPX families. In sum, further studies are needed to explore functions of circRNAs, tRNA, rRNAs, piRNAs, snoRNAs and snRNAs in ferroptosis. Furthermore, the network of factors modulating ferroptosis remains to be established. As ferroptosis is a process of dynamic equilibrium, any alteration of the associated factors may intersect with others. For example, GSH maintains the cytosolic labile iron pool via formation of iron-GSH complexes176. In addition, GSH regulates iron trafficking, and inhibition of GSH synthesis leads to diminished iron efflux following nitric oxide exposure177. Moreover, iron is exported via multidrug resistant protein 1 (MRP1), a known transporter of GSH conjugates178. GSH depletion, MRP1 inhibition or MRP1 knock-out leads to decreased iron release upon nitric oxide treatment179. Conversely, the secondary increase in ROS induced by iron stimulates GSH production, indicating that iron and GSH are interconnected46. Moreover, targets of NRF2 play a critical role in mediating iron/heme metabolism. Both FTL and FTH, the key iron storage protein, as well as FPN, which is responsible for cellular iron efflux, are controlled by NRF2180,181. In addition, a number of integral GSH synthesis and metabolism related enzymes including both the catalytic and modulatory subunits of GCLC, GCLM, GSS, and SLC7A11, are under the control of NRF2182–184. In total, regulation of ferroptosis are linked together, modulation of GSH, iron and NRF2 by ncRNAs may result in further change of each other, and finally alter ferroptosis process.

Clinical application potential of ncRNA-associated ferroptosis

Targeting ncRNAs in cancer has yielded some promising results, however, application of ferroptosis via an ncRNA-dependent manner in clinic is facing obstacles. Inadequate understanding of specific mechanisms results in the limited use of ncRNA modifiers in ferroptosis. Furthermore, cell death occurs in a variety of ways, and numerous ncRNAs may be simultaneously regulated, thus how to ensure that the alteration of associated ncRNAs leads to ferroptosis is another problem. Moreover, ncRNAs act in various ways that may intersect with ferroptosis. For example, ferroptosis inducer miR-210 and H19 could modulate autophagy via targeting BECN1, ATG7, SIRT1, and HIF-1α185–188. In addition, miR-146a could regulat ROS modulator catalase and SOD2 which repressed mitochondrial function189,190. Alteration of autophagy or mitochondrial function resulted in multiple pathologic changes such as neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, vessel remodeling and myocardial fibrosis, thus how to overcome these possible complications should be considered191–194. In addition, some pathways such as the KEAP1-NRF2 axis, is inhibited by multiple miRNAs and lncRNAs and promotes ferroptosis. Nevertheless, the repression of KEAP1-NRF2 results in the defect in cleaning of ROS and leads to susceptibility to DNA damage and tumorigenesis195,196. To solve these problems, future studies should address the following points. First, more ncRNAs should be identified. A ferroptosis-associated ncRNA screening platform should be established to identify the spectrum of ferroptosis associated ncRNAs and those specific to certain cancers. Second, more intensive studies using complex molecular biological experiments, such as chromosome immunoprecipitation, RNA immunoprecipitation, RNA pull-down, luciferase assays, and RNA truncation should be performed to explore the precise roles of ncRNAs in ferroptosis. Third, in order to translate fundamental experimental results into clinic, functions of ncRNAs in ferroptosis should be tested in animal models. Transgenic mouse models should be established to verify the function of ncRNAs more clearly. Fourth, in order to ensure whether ferroptosis is modulated by ncRNAs, accurate detection of ROS and iron levels, and observation of mitochondrial morphology in tumor tissues are needed. Furthermore, primary culture of tumor cells from patients should be performed to explore whether the proliferation of cancer cells is enhanced by Fer-1, which is the specific inhibitor of ferroptosis. The involvement of ncRNAs in ferroptosis in cancer can be verified in knockdown or overexpression studies. Finally, since ferroptosis occurs in not only tumors but also normal tissues, and as above, ferroptosis regulation by ncRNAs may activate other biological processes and even increase the susceptibility to tumorigenesis. Thus, both ferroptosis-related ncRNAs and associated markers of cell death, senescence, and remodeling should be assessed in patients who are suitable for ferroptosis-associated therapy. In addition, adverse events, dose-limiting toxicities and therapeutic effects should be carefully monitored through rigorous detection of organ functions, imaging of vital organs and tumors, and hematological changes during the application of ferroptosis inducers in clinic. After all, as cancer is a developmental process, the collaboration between multidisciplinary teams should be made to obtain rational therapy regimens to enhance therapeutic effect and alleviate complications.

Conclusions and perspectives

Cancer cells may be intrinsically insensitive or evolve and develop resistance to apoptosis, resulting in cancer progression197. Under the development of molecular biological technologies, identification of new targets or methods to eliminate cancer cells has attracted substantial attention. Ferroptosis is a recently recognized form of programmed cell death that relies on excess intracellular ROS and consequent lipid peroxidation198. Ferroptosis has been successfully applied to limit tumor growth and overcome the resistance of cancer cells to apoptosis, indicating that it may be useful as a new therapeutic approach3. Nevertheless, the application of ferroptosis inducers in cancer therapy is limited, mainly because the specific mechanisms underlying ferroptosis remain unexplored.

NcRNAs have been proved to regulate gene expression by various manners. Numerous ncRNAs have been found to regulate behaviors of cancer cells. In recent years, researchers have examined some ferroptosis-associated ncRNAs in cancer cells. Nevertheless, the specific regulatory mechanisms have not been explored. Therefore, wider and deeper studies to explore the function of ncRNAs in ferroptosis are needed. In this review, the landscape of ncRNAs associated with ferroptosis in cancer thus far is summarized. In addition, possible obstacles during application of ncRNA-associated ferroptosis in clinic are put forward and associated solutions are suggested. However, the information summarized in this review is not sufficient to support the application of ferroptosis inducers in cancer, more ncRNAs should be identified and deeper researches should be performed. In conclusion, ncRNAs may become markers to filter cancer patients who are fit for ferroptosis therapy and become therapeutic targets of ferroptosis inducers.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the personnel at Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital for their generous help. This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers LH2019H099), Youth Project of Haiyan Foundation of Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital (grant numbers JJQN2018-15).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by G. Calin

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Lei Zhang, Xiulan Zheng, Wen Cheng

Contributor Information

Lei Zhang, Email: tianwang.3000@163.com.

Xiulan Zheng, Email: zhengxiulan@hrbmu.edu.cn.

Wen Cheng, Email: chengwenhmu@126.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41419-020-02772-8).

References

- 1.Su, Y. L. et al. Myeloid cell-targeted miR-146a mimic inhibits NF-kB-driven inflammation and leukemia progression in vivo. Blood10.1182/blood.2019002045 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim, J. et al. Structure and drug resistance of the Plasmodium falciparum transporter PfCRT. Nature10.1038/s41586-019-1795-x (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rios-Luci, C. et al. Adaptive resistance to trastuzumab impairs response to neratinib and lapatinib through deregulation of cell death mechanisms. Cancer Lett.10.1016/j.canlet.2019.11.026 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon, S. J. et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell149, 1060–1072 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gagliardi, M. et al. Aldo-keto reductases protect metastatic melanoma from ER stress-independent ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis.10, 902 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bibli, S. I. et al. Shear stress regulates cystathionine gamma lyase expression to preserve endothelial redox balance and reduce membrane lipid peroxidation. Redox Biol.28, 101379 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei, S. et al. Arsenic induces pancreatic dysfunction and ferroptosis via mitochondrial ROS-autophagy-lysosomal pathway. J. Hazard. Mater.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121390 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Koppula, P., Zhang, Y., Zhuang, L. & Gan, B. Amino acid transporter SLC7A11/xCT at the crossroads of regulating redox homeostasis and nutrient dependency of cancer. Cancer Commun.38, 12 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang, X. et al. Radiotherapy and immunotherapy promote tumoral lipid oxidation and ferroptosis via synergistic repression of SLC7A11. Cancer Discov.10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0338 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muri, J., Thut, H., Bornkamm, G. W. & Kopf, M. B1 and marginal zone B cellsr but not follicular B2 cells Require Gpx4 to prevent lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Cell Rep.29, 2731–2744 e2734 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie, Y. et al. Ferroptosis: process and function. Cell Death Differ.23, 369–379 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doll, S. et al. FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature575, 693–698 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kajarabille, N. & Latunde-Dada, G. O. Programmed cell-death by ferroptosis: antioxidants as mitigators. Int. J. Mol. Sci.10.3390/ijms20194968 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Hassannia, B., Vandenabeele, P. & Vanden Berghe, T. Targeting ferroptosis to iron out cancer. Cancer Cell35, 830–849 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sui, X. et al. RSL3 drives ferroptosis through GPX4 inactivation and ROS production in colorectal cancer. Front. Pharmacol.9, 1371 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang, H. et al. Dual GSH-exhausting sorafenib loaded manganese-silica nanodrugs for inducing the ferroptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int. J. Pharm.572, 118782 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu, Y. et al. The ferroptosis inducer erastin enhances sensitivity of acute myeloid leukemia cells to chemotherapeutic agents. Mol. Cell. Oncol.2, e1054549 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roh, J. L., Kim, E. H., Jang, H. J., Park, J. Y. & Shin, D. Induction of ferroptotic cell death for overcoming cisplatin resistance of head and neck cancer. Cancer Lett.381, 96–103 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreau, C. et al. Iron as a therapeutic target for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord.33, 568–574 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su, L. et al. Pannexin 1 mediates ferroptosis that contributes to renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Biol. Chem.10.1074/jbc.RA119.010949 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Bella, S. et al. A benchmarking of pipelines for detecting ncRNAs from RNA-Seq data. Brief. Bioinform.10.1093/bib/bbz110 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alzhrani, R. et al. Improving the therapeutic efficiency of noncoding RNAs in cancers using targeted drug delivery systems. Drug Discov. Today10.1016/j.drudis.2019.11.006 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, J. et al. ncRNA-encoded peptides or proteins and cancer. Mol. Ther.27, 1718–1725 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jusic, A., Devaux, Y. & Action, E. U.-C. C. Noncoding RNAs in Hypertension. Hypertension74, 477–492 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao, R. W., Wang, Y. & Chen, L. L. Cellular functions of long noncoding RNAs. Nat. Cell Biol.21, 542–551 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costa, V. et al. MiR-675-5p supports hypoxia induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition in colon cancer cells. Oncotarget8, 24292–24302 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pawlowska, E., Szczepanska, J. & Blasiak, J. The long noncoding RNA HOTAIR in breast cancer: does autophagy play a role? Int. J. Mol. Sci.10.3390/ijms18112317 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Kong, Z. et al. Circular RNA circFOXO3 promotes prostate cancer progression through sponging miR-29a-3p. J. Cell. Mol. Med.10.1111/jcmm.14791 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majidinia, M., Karimian, A., Alemi, F., Yousefi, B. & Safa, A. Targeting miRNAs by polyphenols: novel therapeutic strategy for aging. Biochem. Pharmacol.10.1016/j.bcp.2019.113688 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Tomita, K. et al. MiR-7-5p is a key factor that controls radioresistance via intracellular Fe(2+) content in clinically relevant radioresistant cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.518, 712–718 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang, K. et al. miR-9 regulates ferroptosis by targeting glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase GOT1 in melanoma. Mol. Carcinog.57, 1566–1576 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, M. et al. Long noncoding RNA LINC00336 inhibits ferroptosis in lung cancer by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell Death Differ.26, 2329–2343 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsu, J. L. et al. Glutathione peroxidase 8 negatively regulates caspase-4/11 to protect against colitis. EMBO Mol. Med.10.15252/emmm.201809386 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Koeberle, S. C. et al. Distinct and overlapping functions of glutathione peroxidases 1 and 2 in limiting NF-kappaB-driven inflammation through redox-active mechanisms. Redox Biol.28, 101388 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desideri, E., Ciccarone, F. & Ciriolo, M. R. Targeting glutathione metabolism: partner in crime in anticancer therapy. Nutrients10.3390/nu11081926 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Nunes, S. C. & Serpa, J. Glutathione in ovarian cancer: a double-edged sword. Int. J. Mol. Sci.10.3390/ijms19071882 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Anderton, B. et al. MYC-driven inhibition of the glutamate-cysteine ligase promotes glutathione depletion in liver cancer. EMBO Rep.18, 569–585 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li, P. et al. MicroRNA-218 increases the sensitivity of bladder cancer to cisplatin by targeting Glut1. Cell. Physiol. Biochem.41, 921–932 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang, J., Wang, Y., Guo, Y. & Sun, S. Down-regulated microRNA-152 induces aberrant DNA methylation in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting DNA methyltransferase 1. Hepatology52, 60–70 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lv, L., An, X., Li, H. & Ma, L. Effect of miR-155 knockdown on the reversal of doxorubicin resistance in human lung cancer A549/dox cells. Oncol. Lett.11, 1161–1166 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kefas, B. et al. Pyruvate kinase M2 is a target of the tumor-suppressive microRNA-326 and regulates the survival of glioma cells. NeuroOncology12, 1102–1112 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drayton, R. M. et al. Reduced expression of miRNA-27a modulates cisplatin resistance in bladder cancer by targeting the cystine/glutamate exchanger SLC7A11. Clin. Cancer Res.20, 1990–2000 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pathi, S. S. et al. GT-094, a NO-NSAID, inhibits colon cancer cell growth by activation of a reactive oxygen species-microRNA-27a: ZBTB10-specificity protein pathway. Mol. Cancer Res.9, 195–202 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong, Z. et al. Effect of microRNA-21 on multidrug resistance reversal in A549/DDP human lung cancer cells. Mol. Med. Rep.11, 682–690 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He, H. W., Wang, N. N., Yi, X. M., Tang, C. P. & Wang, D. Low-level serum miR-24-2 is associated with the progression of colorectal cancer. Cancer Biomark.21, 261–267 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang, H. et al. MicroRNA-497 regulates cisplatin chemosensitivity of cervical cancer by targeting transketolase. Am. J. Cancer Res.6, 2690–2699 (2016). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang, D. et al. Role and mechanisms of microRNA503 in drug resistance reversal in HepG2/ADM human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol. Med. Rep.10, 3268–3274 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu, J. et al. Knockdown of long non-coding RNA XIST inhibited doxorubicin resistance in colorectal cancer by upregulation of miR-124 and downregulation of SGK1. Cell. Physiol. Biochem.51, 113–128 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ma, H. et al. Identification of reciprocal microRNA-mRNA pairs associated with metastatic potential disparities in human prostate cancer cells and signaling pathway analysis. J. Cell. Biochem.120, 17779–17790 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghanbarian, M., Afgar, A., Yadegarazari, R., Najafi, R. & Teimoori-Toolabi, L. Through oxaliplatin resistance induction in colorectal cancer cells, increasing ABCB1 level accompanies decreasing level of miR-302c-5p, miR-3664-5p and miR-129-5p. Biomed. Pharmacother.108, 1070–1080 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh, S., Shukla, G. C. & Gupta, S. MicroRNA regulating glutathione S-transferase P1 in prostate cancer. Curr. Pharmacol. Rep.1, 79–88 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uchida, Y. et al. MiR-133a induces apoptosis through direct regulation of GSTP1 in bladder cancer cell lines. Urol Oncol.31, 115–123 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moriya, Y. et al. Tumor suppressive microRNA-133a regulates novel molecular networks in lung squamous cell carcinoma. J. Hum. Genet.57, 38–45 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin, C., Xie, L., Lu, Y., Hu, Z. & Chang, J. miR-133b reverses cisplatin resistance by targeting GSTP1 in cisplatin-resistant lung cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Med.41, 2050–2058 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xue, J. et al. The hsa-miR-181a-5p reduces oxidation resistance by controlling SECISBP2 in osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord.19, 355 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu, Y. et al. miR-17* suppresses tumorigenicity of prostate cancer by inhibiting mitochondrial antioxidant enzymes. PLoS ONE5, e14356 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu, Z. et al. miR-17-3p downregulates mitochondrial antioxidant enzymes and enhances the radiosensitivity of prostate cancer cells. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids13, 64–77 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu, Q., Bai, W., Huang, F., Tang, J. & Lin, X. Downregulation of microRNA-196a inhibits stem cell self-renewal ability and stemness in non-small-cell lung cancer through upregulating GPX3 expression. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol.115, 105571 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Choi, J. Y., An, B. C., Jung, I. J., Kim, J. H. & Lee, S. W. MiR-921 directly downregulates GPx3 in A549 lung cancer cells. Gene700, 163–167 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arefieva Olga, D., Vasilyeva Marina, S., Zemnukhova Liudmila, A. & Timochkina Anna, S. Heterogeneous photo-Fenton oxidation of lignin of rice husk alkaline hydrolysates using Fe-impregnated silica catalysts. Environ. Technol.10.1080/09593330.2019.1697376 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Abeyawardhane, D. L. & Lucas, H. R. Iron redox chemistry and implications in the Parkinson’s disease brain. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev.2019, 4609702 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang, F. et al. Iron and leukemia: new insights for future treatments. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res.38, 406 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hamara, K. et al. Alterations in expression profile of iron-related genes in colorectal cancer. Mol. Biol. Rep.40, 5573–5585 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kindrat, I. et al. MicroRNA-152-mediated dysregulation of hepatic transferrin receptor 1 in liver carcinogenesis. Oncotarget7, 1276–1287 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Greene, C. M., Varley, R. B. & Lawless, M. W. MicroRNAs and liver cancer associated with iron overload: therapeutic targets unravelled. World J. Gastroenterol.19, 5212–5226 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kong, Y. et al. Ferroportin downregulation promotes cell proliferation by modulating the Nrf2-miR-17-5p axis in multiple myeloma. Cell Death Dis.10, 624 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Babu, K. R. & Muckenthaler, M. U. miR-20a regulates expression of the iron exporter ferroportin in lung cancer. J. Mol. Med.94, 347–359 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen, Y. et al. Myeloid zinc-finger 1 (MZF-1) suppresses prostate tumor growth through enforcing ferroportin-conducted iron egress. Oncogene34, 3839–3847 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stuhn, L., Auernhammer, J. & Dietz, C. pH-depended protein shell dis- and reassembly of ferritin nanoparticles revealed by atomic force microscopy. Sci. Rep.9, 17755 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chan, J. J. et al. A FTH1 gene:pseudogene:microRNA network regulates tumorigenesis in prostate cancer. Nucleic Acids Res.46, 1998–2011 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shpyleva, S. I. et al. Role of ferritin alterations in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat.126, 63–71 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chekhun, V. F. et al. Iron metabolism disturbances in the MCF-7 human breast cancer cells with acquired resistance to doxorubicin and cisplatin. Int. J. Oncol.43, 1481–1486 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoshioka, Y., Kosaka, N., Ochiya, T. & Kato, T. Micromanaging iron homeostasis: hypoxia-inducible micro-RNA-210 suppresses iron homeostasis-related proteins. J. Biol. Chem.287, 34110–34119 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gee, H. E., Ivan, C., Calin, G. A. & Ivan, M. HypoxamiRs and cancer: from biology to targeted therapy. Antioxid. Redox Signal.21, 1220–1238 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zou, C. et al. Heme oxygenase-1 retards hepatocellular carcinoma progression through the microRNA pathway. Oncol. Rep.36, 2715–2722 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lobello, N. et al. Ferritin heavy chain is a negative regulator of ovarian cancer stem cell expansion and epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget7, 62019–62033 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sriramoju, B., Kanwar, R. K. & Kanwar, J. R. Lactoferrin induced neuronal differentiation: a boon for brain tumours. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci.41, 28–36 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cloer, E. W., Goldfarb, D., Schrank, T. P., Weissman, B. E. & Major, M. B. NRF2 activation in cancer: from DNA to protein. Cancer Res.79, 889–898 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gai, C. et al. Acetaminophen sensitizing erastin-induced ferroptosis via modulation of Nrf2/heme oxygenase-1 signaling pathway in non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Cell. Physiol.10.1002/jcp.29221 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yamamoto, S. et al. The impact of miRNA-based molecular diagnostics and treatment of NRF2-stabilized tumors. Mol. Cancer Res.12, 58–68 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tian, Y. et al. Emerging roles of Nrf2 signal in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol.9, 14 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang, B., Teng, Y. & Liu, Q. MicroRNA-153 regulates NRF2 expression and is associated with breast carcinogenesis. Clin. Lab.62, 39–47 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Qaisiya, M., Coda Zabetta, C. D., Bellarosa, C. & Tiribelli, C. Bilirubin mediated oxidative stress involves antioxidant response activation via Nrf2 pathway. Cell. Signal.26, 512–520 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Narasimhan, M. et al. Identification of novel microRNAs in post-transcriptional control of Nrf2 expression and redox homeostasis in neuronal, SH-SY5Y cells. PLoS ONE7, e51111 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shi, L. et al. miR-340 reverses cisplatin resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines by targeting Nrf2-dependent antioxidant pathway. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev.15, 10439–10444 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hamalainen, M. et al. NRF1 and NRF2 mRNA and protein expression decrease early during melanoma carcinogenesis: an insight into survival and MicroRNAs. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev.2019, 2647068 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yin, Y. et al. miR1443p regulates the resistance of lung cancer to cisplatin by targeting Nrf2. Oncol. Rep.40, 3479–3488 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Raghunath, A., Sundarraj, K., Arfuso, F., Sethi, G. & Perumal, E. Dysregulation of Nrf2 in hepatocellular carcinoma: role in cancer progression and chemoresistance. Cancers10.3390/cancers10120481 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 89.Zhou, C. et al. MicroRNA-144 modulates oxidative stress tolerance in SH-SY5Y cells by regulating nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2-glutathione axis. Neurosci. Lett.655, 21–27 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhou, S. et al. miR-144 reverses chemoresistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines by targeting Nrf2-dependent antioxidant pathway. Am. J. Transl. Res.8, 2992–3002 (2016). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wu, L. et al. lncRNA KRAL reverses 5-fluorouracil resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by acting as a ceRNA against miR-141. Cell Commun. Signal.16, 47 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fabrizio, F. P., Sparaneo, A., Trombetta, D. & Muscarella, L. A. Epigenetic versus genetic deregulation of the KEAP1/NRF2 axis in solid tumors: focus on methylation and noncoding RNAs. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev.2018, 2492063 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shi, L. et al. MiR-141 activates Nrf2-dependent antioxidant pathway via down-regulating the expression of Keap1 conferring the resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells to 5-fluorouracil. Cell. Physiol. Biochem.35, 2333–2348 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Khan, A. U. H. et al. Human leukemic cells performing oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) generate an antioxidant response independently of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. EBioMedicine3, 43–53 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Akdemir, B., Nakajima, Y., Inazawa, J. & Inoue, J. miR-432 induces NRF2 stabilization by directly targeting KEAP1. Mol. Cancer Res.15, 1570–1578 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu, M. et al. Methylseleninic acid activates Keap1/Nrf2 pathway via up-regulating miR-200a in human oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Biosci. Rep.10.1042/BSR20150092 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 97.Karihtala, P. et al. Expression levels of microRNAs miR-93 and miR-200a in pancreatic adenocarcinoma with special reference to differentiation and relapse-free survival. Oncology96, 164–170 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]