Abstract

Circulation through cerebral collaterals can maintain tissue viability until reperfusion is achieved. However, collateral circulation is time limited, and failure of collaterals is accelerated in the aged. Remote ischemic perconditioning (RIPerC), which involves inducing a series of repetitive, transient peripheral cycles of ischemia and reperfusion at a site remote to the brain during cerebral ischemia, may be neuroprotective and can prevent collateral failure in young adult rats. Here, we demonstrate the efficacy of RIPerC to improve blood flow through collaterals in aged (16–18 months of age) Sprague Dawley rats during a distal middle cerebral artery occlusion. Laser speckle contrast imaging and two-photon laser scanning microscopy were used to directly measure flow through collateral connections to ischemic tissue. Consistent with studies in young adult rats, RIPerC enhanced collateral flow by preventing the stroke-induced narrowing of pial arterioles during ischemia. This improved flow was associated with reduced early ischemic damage in RIPerC treated aged rats relative to controls. Thus, RIPerC is an easily administered, non-invasive neuroprotective strategy that can improve penumbral blood flow via collaterals. Enhanced collateral flow supports further investigation as an adjuvant therapy to recanalization therapy and a protective treatment to maintain tissue viability prior to reperfusion.

Subject terms: Diseases of the nervous system, Neuro-vascular interactions, Neurology, Preclinical research

Introduction

Ischemic stroke is a devastating cerebral disease that occurs when arteries supplying the brain are obstructed. Ischemia leads to insufficient nutrient and oxygen supply to meet metabolic demand of the brain, thus inducing the damage or death of brain cells. Cerebral collaterals are subsidiary vascular channels in the cerebral circulation which can sustain blood flow to ischemic tissue when principal vascular routes fail1–6. Blood flow through the collateral circulation is a primary determinant of the degree of ischemia in the penumbra, and thus a major predictor of infarct size and growth8,3,7,9–12. Cerebral collaterals can be classified as primary or secondary collaterals. The primary collaterals refer to the Circle of Willis, which allows blood flow exchange between anterior and posterior circulation and between hemispheres. Secondary collaterals include the pial or leptomeningeal collaterals5. Pial collaterals are anastomotic connections located on the cortical surface that connect distal branches of adjacent arterial networks (e.g. anterior cerebral artery (ACA)–middle cerebral artery (MCA); middle cerebral artery (MCA)–posterior cerebral artery (PCA) ACA–MCA; MCA–PCA13,2,14,15). MCA occlusion is the most common cause of ischemic stroke. Notably, when MCA occlusion occurs, pial collaterals become patent and can provide compensatory blood flow from the ACA and/or PCA to the ischemic penumbra via anastomotic connections with the MCA. However, collateral flow is time limited and can fail over time16–21. The failure of collaterals during stroke leads to the progression of the penumbra to irreversible ischemic infarct and reduces benefit from recanalization therapies19,22–24.

Intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (IV r-tPA) is the only FDA approved medical treatment of ischemic stroke, but requires administration within 4.5 h of symptom onset25–28. Although proven effective when administered within this therapeutic window, approximately half of patients treated with intravenous r-tPA do not benefit29. It is likely that insufficient collateral flow that leads to rapid tissue infarction accounts for the lack of benefit due to recanalization in many of these patients. Supporting this, multiphase CT angiography data from the ESCAPE (Endovascular treatment for Small Core and Anterior circulation Proximal occlusion with Emphasis on minimizing CT to recanalization times) trial identified a strong association between pre-treatment cerebral pial collaterals and favorable outcome after recanalization30–32. Similarly, patients with "slow-growing infarcts" due to good collateral circulation in the (DWI or CTP Assessment with Clinical Mismatch in the Triage of Wake-Up and Late Presenting Strokes Undergoing Neurointervention with Trevo) and DEFUSE3 (Endovascular Therapy Following Imaging Evaluation for Ischemic Stroke 3) trials benefitted from late thrombectomy (6 to 24 h after stroke onset), likely due to sufficient collateral circulation to maintain tissue viability prior to recanalization up to 24 h post stroke33–42. Rates of hemorrhagic transformation after recanalization are also reduced in patients with good collateral blood flow4,43,44. Strategies that can augment collateral blood flow to reduce expansion of the infarct core before recanalization treatment may therefore extend the time window for reperfusion interventions and allow more patients to benefit3.

Remote ischemic conditioning is a therapeutic process induced by series of repetitive, transient episodes of ischemia/reperfusion on a non-vital remote organ, such as limb, to provide endogenous protection to ischemia in vital organs such as the heart or brain45,17,46,47 (9,20). Remote ischemic perconditioning (RIPerC) involves starting treatment after the onset of vital organ ischemia but before reperfusion17,48,49. RIPerC induced by bilateral femoral occlusion (BFO) within 1 h post dMCAO is effective in preventing collateral collapse and reducing early ischemic damage in young adult rats17. However, aging is one of the primary risk factors for ischemic stroke and it is known that the brain of the elderly has reduced ischemic tolerance50,9,51,52. Preclinical studies have reported that increasing age is associated with rarefaction of cerebral collaterals, leading to insufficient ability to maintain blood flow during ischemia9,50,3,16,53. Notably, the hemodynamic evolution of the pial collateral circulation is also influenced by aging. Aged rats exhibit rapid and more severe failure of pial collaterals relative to young rats, and significantly greater volumes of early ischemic damage16,53. Whether RIPerC can prevent the collapse of collateral flow in aged rats is not known. Given that the cardioprotective effects of RIPerC are age dependent, it is important to confirm protective effects on collateral circulation and ischemic injury in aged animals that more closely model the clinical population54. To provide further evidence in support bench to bedside translation of RIPerC by directly demonstrating protection of collateral flow, we examined hemodynamic changes in pial collateral vessels after RIPerC treatment in aged rats. Our findings demonstrated that RIPerC induced by BFO 1 h after distal middle cerebral artery occlusion (dMCAO) is effective in reducing early ischemic damage and improves collateral blood flow by preventing collateral narrowing in aged animals.

Results

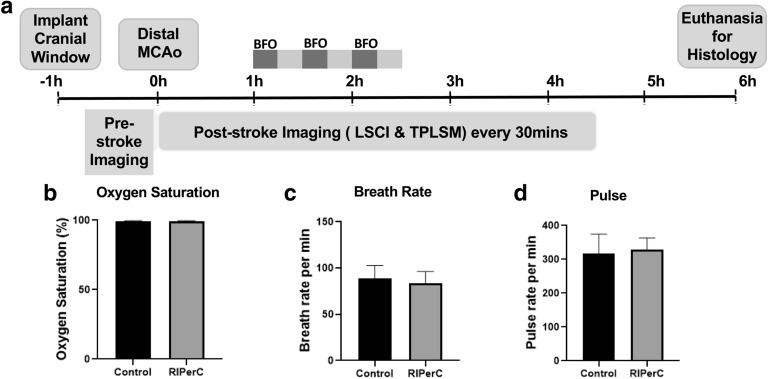

Pial collateral flow was measured immediately before ischemic onset and for 4.5 h after dMCAO (at intervals of 30 min, Fig. 1a) using LSCI and TPLSM. LSCI and TPLSM were used to create high-spatiotemporal resolution maps of blood flow in pial vessels in the region of ischemia, including measures of regional flow (LSCI, Fig. 2) as well as pial vessel diameter and RBC velocity (TPLSM, Figs. 3–5) (1). Importantly, physiological parameters were not significantly altered by ischemia or repeated imaging (Fig. 1b-d).

Figure 1.

Experimental design and physiological parameters of aged rats treated with RIPerC after dMCAO. (a) Experimental timeline (b-d) Physiological parameters of RIPerC and sham treatment rats during imaging after dMCAO.

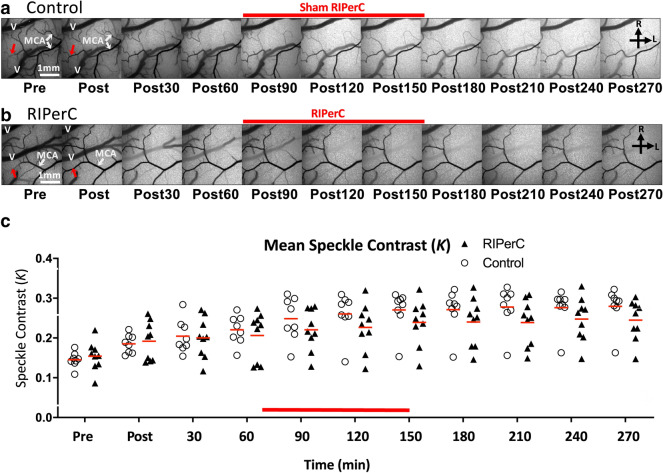

Figure 2.

Laser speckle contrast imaging of collateral blood flow. (a-b) Representative LSCI derived image sequences of speckle contrast showing flow on the cortical surface before and after dMCAO. Images showing flow changes over 270 min (4.5 h) post are illustrated for control (a) and RIPerC rats (b). Immediately after dMCAO, robust anastomotic connections between distal segments of the ACA and MCA were observed in both groups. (c) LSCI revealed an increase of speckle contrast value after dMCAO in both control and RIPerC treated group. Mean speckle contrast values (K) are shown in (c).

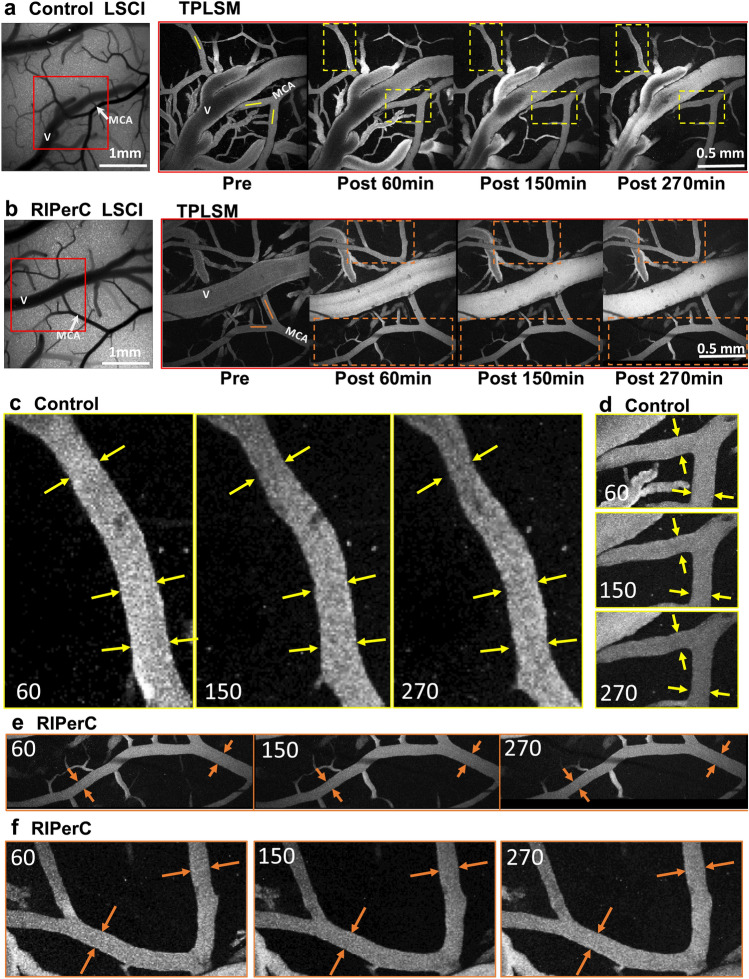

Figure 3.

Representative images from TPLSM of collateral blood flow after dMCAO. (a,b) Representative images of a control rat (a) and RIPerC-treated rat (b). Panels of TPLSM images on the right show maximum intensity projections from region demarcated with rectangular box in LSCI images. Scale bar, 1 mm. (c,d) Magnified images showing vessels demarcated by the yellow boxes for the control rat shown in (a). Yellow arrows denote vessel diameter 60 min after dMCAO, and are superimposed on the same vessel and region 150 and 270 min after dMCAO. Clear constriction of vessel lumen diameter is apparent in control rats. (e,f) Magnified images of vessels demarcated by the orange boxes in the RIPerC treated rat in (b). Again, orange arrows show vessel diameter at 60 min after dMCAO and are repeated in images acquired 150 and 270 min after ischemic onset. With RIPerC, vessel diameter is maintained throughout the imaging period.

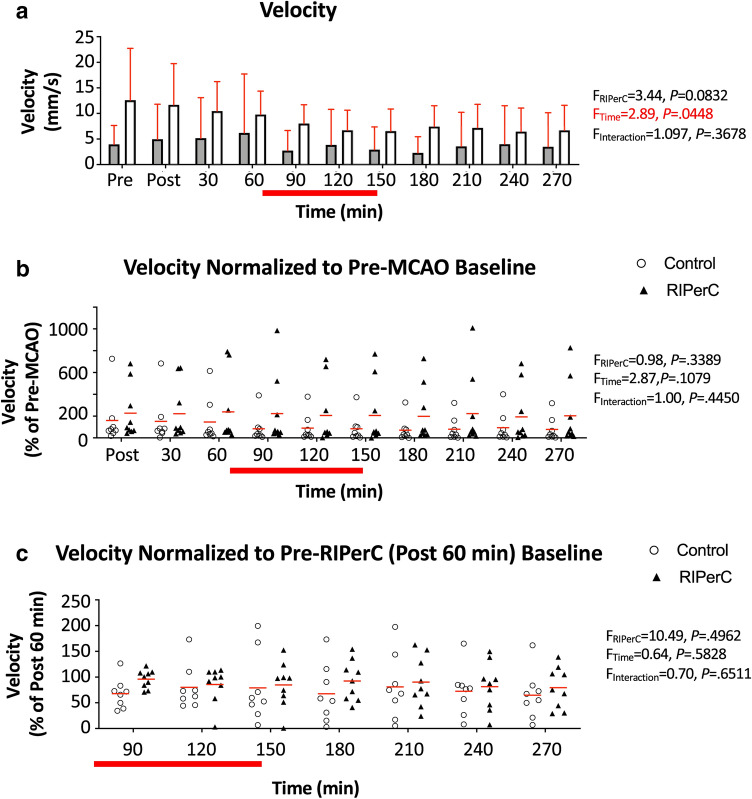

Figure 5.

Flow velocity in pial arterioles after dMCAO and RIPerC. (a) Mean RBC velocity of pial vessels from control (sham treated) and RIPerC treated aged rats (bars show mean ± SD). Two-way ANOVA confirmed a significant main effect of Time and a trend towards a main effect of Treatment on flow velocity in measured segments. To better illustrate diameter changes due to stroke and treatment, (b) shows flow velocity data normalized to values measured prior to dMCAO. (c) shows flow velocity normalized to values measured 60 min after ischemic onset (i.e. post dMCAO but pre-RIPerC or sham treatment). Individual means for each animal are plotted, and red lines show the group mean. For both (b) and (c), two-way ANOVAs demonstrated no significant main effects of Time or Treatment and no significant Time × Treatment interactions.

Regional changes in collateral blood flow in aged rats after RIPerC

Figure 2 shows LSCI derived maps of speckle contrast showing flow changes over 270 min (4.5 h) post stroke in aged control rats (Fig. 2a) and aged RIPerC treated rats (Fig. 2b). As previously reported, robust anastomotic connections between the distal segments of MCA and ACA are visible after ischemic onset. These anastomoses are apparent in both groups (red arrows). In aged controls, penumbral flow decreased during the imaging period (as indicated by a consistent reduction in visible pial vessels and increase in speckle contrast brightness during the imaging period (Fig. 2a). Qualitatively, this reduction in flow (increased speckle contrast) appeared less severe in RIPerC treated rats (Fig. 2b). Mean speckle contrast values (K) acquired from LSCI data are shown in Fig. 2c. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Time [F (10,150) = 35.67, P < 0.0001), as well as a significant Time × Treatment interaction (F (10,150) = 1.959, P = 0.0416); Treatment, n.s.].

Hemodynamics of collaterals in aged rats after dMCAO

TPLSM was performed to directly assess the luminal diameter and RBC velocity in segments of the distal MCA within or adjacent collateral anastomoses with the ACA in aged rats treated with RIPerC (Fig. 3a) or sham treatment (Controls, Fig. 3b) after distal dMCAO. In Fig. 3, panels at left show LSCI maps before dMCAO. Panels from left to right show TPLSM images from the region demarcated by the red box in the LSCI image acquired before dMCAO then 60 , 150 (during the 3rd cycle of BFO releasing or sham treatment), and 270 min after dMCAO, respectively. Narrowing of distal MCA segments over time after dMCAO was apparent in aged controls, but qualitatively less severe in RIPerC-treated animals. Representative TPLSM images are shown in Fig. 3a,b, with magnified images of the vessels demarcated by boxes in Fig. 3a,b shown in Fig. 3c-f. Arrows in Fig. 3c-f highlight the diameter of these vessels immediately prior to RIPerC (at 60 min after dMCAO). These arrows are then superimposed at the same location on the same vessels imaged at 150 and 270 min after dMCAO for the representative control rat (Fig. 3c,d) and RIPerC treated rat (Fig. 3e,f). Notably, in control rats (Fig. 3c,d) the vessel diameters narrow over time after stroke, such that space between the vessel lumen and the arrows demarcating diameter at 60 min after dMCAO is apparent. Contrasting this, vessel diameters remain stable in RIPerC treated rats (Fig. 3e,f).

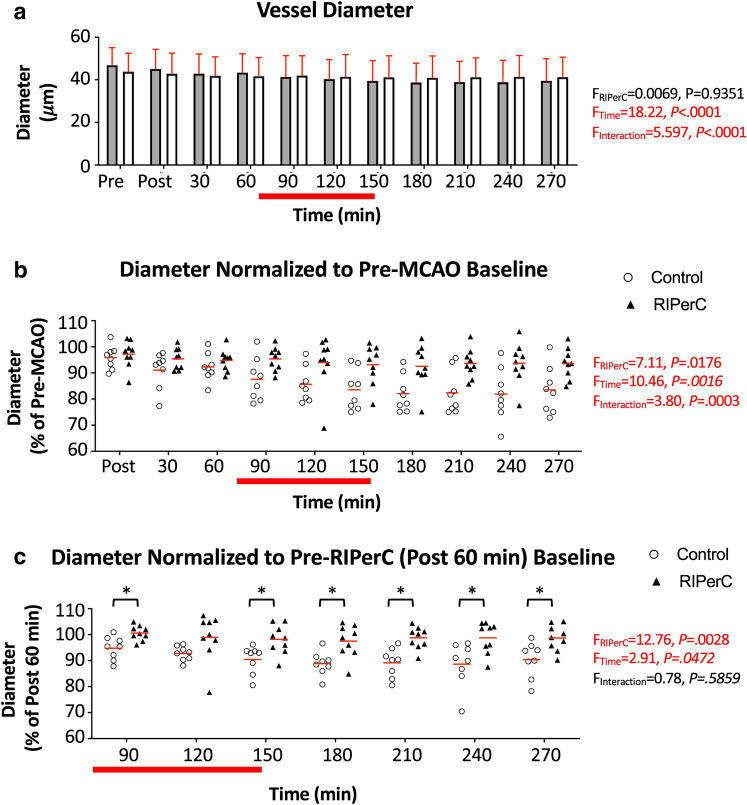

Figure 4a shows mean diameter of these pial vessels (within or adjacent ACA-MCA collaterals) at all imaging time points. Mean diameters of the control and RIPerC treated rats at pre-MCAO baseline were were 46.84 ± 2.91 and 43.85 ± 2.88 µm, respectively. Two-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant main effect of Time (F(3.209, 48.13) = 18.22, P < 0.0001) and a significant interaction of Time and Treatment (F(10, 150) = 5.597, P < 0.0001) on vessel diameter. To isolate diameter changes over time after stroke, vessel diameters were data normalized to baseline values prior to dMCAO (normalized within each vessel then averaged for a mean per animal, Fig. 4b). Two-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant main effect of Time (F(1.460, 21.90) = 10.46, P = 0.0016) and Treatment (F(1,15) = 7.106, P = 0.0176) on pial arteriole diameter normalized to pre-MCAO baseline, as well as a significant Time × Treatment interaction (F(9,135) = 3.802, P = 0.0003). Post hoc comparisons did not identify any significant differences between treatment groups at individual time-points. To further isolate treatment effects and compensate for any potential variation in blood flow after dMCAO but prior to treatment, Fig. 4c shows diameters normalized to values measured 60 min after ischemic onset (but prior to RIPerC or sham treatment). Two-Way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Treatment (F(1,15) = 12.76, P = 0.0028) and Time (F(2.886,43.29) = 2.905, P = 0.0472; Time × Treatment interaction, n.s). Holm–Sidak's post hoc comparisons revealed that RIPerC-treated rats had significantly larger diameters (P < 0.05) at all-time points after the initiation of the first BFO clamp, with the exception of 120 min post dMCAO. Thus, consistent with findings in younger adult rats17, RIPerC protected against collateral narrowing in aged rats.

Figure 4.

Diameter changes due to dMCAO and RIPerC. (a) Mean diameter of vessels measured in control (sham treated) and RIPerC treated aged rats (bars show mean ± SD). Two-way ANOVA confirmed a significant main effect of Time and a significant Time × Treatment interaction (F, P values denoted on figure) on pial vessel diameter. To better illustrate diameter changes due to stroke and treatment, (b) shows pial diameter data normalized to values measured prior to dMCAO. Individual means for each animal are plotted, and red lines show the group mean. Two-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant main effect of Time and Treatment on pial arteriole diameter, as well as a significant Time × Treatment interaction. To compensate for potential variation in blood flow after dMCAO but prior to treatment, and to isolate treatment effects, (c) shows diameters normalized to values measured 60 min after ischemic onset (i.e. post dMCAO but pre-RIPerC or sham treatment). Two-Way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Treatment and Time (Time × Treatment interaction n.s.). Holm–Sidak's post hoc comparisons revealed that RIPerC-treated rats had significantly larger diameters (P < 0.05) at all-time points after the initiation of the first BFO clamp, with the exception of 120 min after dMCAO.

Figure 5a shows mean changes in red blood cell (RBC) velocity from the same arterioles corresponding the diameter measurements in Fig. 4. Given their position near or within anastomoses at the distal ends of the MCA territory, flow velocity was variable between vessels before and after dMCAO. However, all segments analyzed exhibited a reversal of flow direction consistent with retrograde flow from ACA to MCA. Two-way ANOVA on flow velocity revealed a significant main effect of Time (F(3.041, 45.62) = 2.892, P = 0.0448) and a statistical trend towards an effect of Treatment group (F(1, 15) = 3.444, P = 0.0832, reflecting a trend towards a sample with higher velocities before and after stroke in the RIPerC group). Flow velocity normalized to baseline prior to dMCAO and values 60 min after dMCAO are shown in Fig. 5b,c, respectively, to highlight changes due to stroke and treatment. In both cases, there were no significant main effects of Time or Treatment and no significant Time × Treatment interactions.

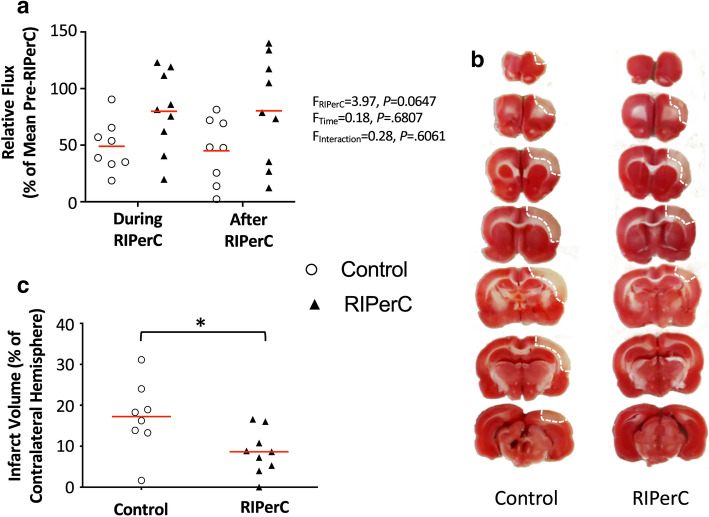

RBC flux is a critical measure of perfusion, as it is proportional to the oxygen and nutrient carrying capacities of a blood vessel55,56. In Fig. 6a, a measure of Relative Flux (see “Materials and methods”) is shown to illustrate changes in flow from post dMCAO baseline during and after RIPerC treatment. Two-way ANOVA demonstrates a statistical trend towards a main effect of Treatment on Relative Flux (F(1, 15) = 3.974, P = 0.0647), suggesting that flux was greater in treated rats during and after RIPerC.

Figure 6.

Effects of RIPerC on relative flux and infarct volume in aged rats after dMCAO. (a) Relative flux for arteriole segments within or downstream of ACA–MCA collateral anastomoses in RIPerC treated and control rats are shown. Relative flux shows overall flow through these segments during and after RIPerC (or sham treatment), accounting for diameter and velocity measurements, relative to flux prior to treatment. Individual means for each animal are plotted, and red lines show the group mean. RIPerC exhibited a strong statistical trend towards a persistent improvement in flux, with flux relative to pre-treatment values approximately 163% and 178% greater during and after treatment, respectively, in RIPerC treated rats relative to controls. The volume of early ischemic damage from TTC staining for RIPerC and control rats is shown in (b) and (c). A significant reduction in early infarct was observed in RIPerC treated aged rats.

Early ischemic damage

All rats were euthanized at 6 h after dMCAO and stained with TTC to demarcate regions with early ischemic damage (Fig. 6b). As illustrated in Fig. 6c, a significantly smaller volume of early ischemic damage was found in aged rats treated with RIPerC relative to sham treated rats (P = 0.0241).

Discussion

Previous studies suggest that pial collateral blood flow fails over time in aged rats after dMCAO, exacerbating the insufficient perfusion of the penumbra and leading to greater ischemic damage16. Collateral failure is also associated with futile recanalization and poor outcome in stroke patients19,22,57,24. Clinically, collateral therapeutics that can preserve collateral flow may be able "freeze" penumbra before recanalization via thrombolysis or thrombectomy and thereby reduce stroke severity58. Maintaining collateral flow prior to recanalization may be particularly important in aging populations with impaired collateral dynamics.

Several reports suggest that RIPerC can enhance cerebral blood flow in preclinical models of stroke. Studies using regional imaging of cerebral blood flow in mice suggest that RIPerC is effective alone and in combination with i.v. r-tPA in enhancing penumbral flow in young male mice, ovarectomized female mice, and 12-month old male mice46,47,59,49. Our previous research with LSCI and TPLSM demonstrate that RIPerC improves pial collateral flow by preventing collateral narrowing in young adult rats after dMCAO17. However, this is the first study to use TPLSM to directly record the hemodynamic effects of RIPerC on collaterals in aged animals. A rarefaction of cerebral arterioles and decrease in capillary density occurs with aging in humans, non-human primates, and rodents60–68. Advanced age is also associated with narrower lumen diameters and increased tortuosity of cerebral vessels66,69,70. These changes in the cerebral circulation increase vascular resistance, thereby reducing tissue perfusion during ischemia and leading to significantly larger regions of infarction71,9,53,72. Moreover, vasodilation and vasoreactivity of both peripheral and cerebral circulation may be impaired with aging73–76. Combined, these changes could dramatically reduce the compensatory capabilities of the cerebral collateral circulation, and impair the efficacy of collateral therapeutics in aged stroke patients. To be consistent with the Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable (STAIR) recommendations77,78, which were established in an attempt to improve translation of preclinical stroke therapies, it is important then to directly verify the collateral effects of RIPerC in aged animals that better approximate human stroke patients. Our combination of LSCI and TPLSM in aged rats provides high resolution data on the dynamics of collateral connections between the ACA and MCA during MCAO and treatment with RIPerC.

The combination of TPLSM and LSCI in aged rats provided both wide field assessment of penumbral blood flow as well as precise quantification of the diameter of pial vessels and the direction and velocity of blood flow within individual collateral segments. The speckle contrast (K) measured with LSCI (Fig. 2) suggested enhancement of blood flow in RIPerC treated rats. More quantitative analyses using TPLSM (Figs. 3–6), confirmed that pial collaterals of aged control rats constrict after dMCAO, reaching approximately 83% of prestroke baseline diameter by 4.5 h after stroke onset. Importantly, consistent with our findings in young adult rats, collateral failure was significantly reduced by RIPerC treatment, with pial arteriole diameter measured at approximately 97% of pre-treatment values 4.5 h hour after dMCAO onset. This increased diameter was associated with a strong statistical trend towards a persistent increase in flux through collaterals in RIPerC treated aged rats (due to diameter changes rather than RIPerC induced changes in flow velocity), and significantly smaller volumes of ischemic damage at 6 h post dMCAO. Notably, our assessment of pial collaterals focused on distal segments of the MCA within or immediately adjacent anastomoses with distal ACA segments. These vessels exhibited flow reversal due to retrograde flow from the ACA to the MCA territory, and in some cases demonstrated dramatic increases in flow velocity following MCAO. However, consistent with our previous studies of aged animals16, vessel diameter narrowed over time blood flow velocity was reduced over time in aged control animals. Consequently, flux through these collateral connections fell to ~ 45% of Pre-RIPerC values following the sham treatment period in control animals (as compared to ~ 80% following RIPerC in treated rats). Recently, Zhu et al.79 used Doppler optical coherence tomography to demonstrate spatiotemporally dynamic changes in pial collateral flow in young adult rats following distal MCAO and treatment with sensory stimulation. Their data shows significant reductions in flow velocity and flux in ischemic tissue that were stable or increased over time. While there are methodological differences (e.g. different anaesthetics, protocols for inducing MCAO, imaging window preparations, and ages of animals), their findings in 3–4 month old rats are consistent with our previous observation that compensatory increases in flow velocity can maintain stable flow through collaterals in young adult but not aged rats16. Notably, in the majority of animals, Zhu et al.79 reported a significant subset of MCA branches continued to show anterograde blood flow patterns over time despite severing of the cortical MCA. Moreover, sensory stimulation had protective effects that were greater in the vessels with anterograde flow relative to retrograde flow branches. The authors discuss a model illustrating that flow from a restricted number of collateral connections with the ACA (i.e. retrograde vessels) could provide flow through the vascular network and account for anterograde flow in imaged vessels. This would be consistent with our data: While we report only retrograde flowing vessels, our TPLSM imaging was focused on collateral connections between the most distal branches of the ACA and MCA where flow reversal would be predicted. We would predict that other interconnected vessels downstream of these regions would show anterograde flow as described. Zhu et al.79 do not report a narrowing of pial vessels consistent with our data. However, whereas our study focused on pial arterioles within or adjacent ACA/MCA anastomoses at the distal ends of the vascular territories, Zhu et al.79 analyzed branches throughout their imaging window. Notably, the mean radius at baseline sampled by Zhu et al.79 was greater than 60 µm, whereas the mean diameter of the vessels measured in our RIPerC and sham treatment groups was 45.26 ± 2.02 µm. Thus, their study provides a comprehensive analysis of changes in flow in larger pial vessels throughout the ischemic region, but might underestimate the dynamics and potentially important contributions of smaller arterioles that constitute the collateral connections.

Our findings of RIPerC in aged rats provide further scientific rationale for exploring translation of RIPerC treatment from bench to bedside. Notably, a transient vasodilatory effect of RIPerC in the cerebral circulation has been reported in humans in clinical studies of subarachnoid hemorrhage80. The first randomized trial to examine adjunctive neuroprotective effects of RIPerC to r-tPA treatment in acute stroke patients in the prehospital setting has been conducted81,82. This trial found the approach was safe and no intolerable discomfort or adverse events were caused by RIPerC. After adjustment for baseline severity of hypo-perfusion, there was evidence of tissue protection by RIPerC in post hoc MRI data analysis using a voxel based logistic regression method47,81. Moreover, significantly lower NIHSS scores and higher frequency of TIA diagnosis were also observed at admission for RIPerC treated patients relative to controls. Remote ischemic conditioning before and after recanalization in patients with large-vessel occlusions of the anterior circulation has also been shown to be safe and feasible preliminary clinical investigations83,84. Thus, RIPerC is a promising adjunctive therapy to spare functionally intact brain tissues before recanalization or after treatment.

Several important questions regarding the mechanisms and efficacy of RIPerC as a collateral therapeutic and neuroprotective strategy for ischemic stroke remain. Notably, our study used urethane anaesthetized animals, and it would be ideal define the hemodynamics of RIPerC in unanaesthetized animals. Similarly, while cranial windows allow for stable imaging, use of a thinned skull preparation85 could reduce potential confounds due to skull removal and replacement with a glass window. Moreover, it is important to note that most preclinical studies of RIPerC (including ours) induce RIPerC on rodent hind limbs via bilateral femoral ligation59,49,17. However, clinical studies generally involve upper limb ischemia via inflation of a blood pressure cuff82,54,81. Consistent methods of remote conditioning and consistent periods of ischemia and reperfusion should be used to better validate RIPerC. Additionally, the mechanisms of RIPerC with respect to neuroprotection and collateral dynamics remain to be elucidated. Raised intracranial pressure may contribute to collateral failure86–90, and may be accelerated in the aged, and the protective effects of RIPerC on the brain and vasculature may act reduce intracranial pressure to preserve collaterals. However, preliminary studies in clinical populations did not identify an effect of RIPerC on intracranial pressure84. Nitric oxide and its metabolites are thought to contribute to protection due to remote ischemic conditioning (RIC) protection in liver and cardiac ischemia. Notably, treated mice have elevated nitrite and nitrate levels in the blood, liver, and heart and the cardioprotective effects of RIC are lost in endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) knockout mice95, 91–98. Plasma nitrite levels also increase after remote ischemic conditioning in healthy human volunteers95. The link between nitric oxide and collateral dynamics in cerebral ischemia remains to be further investigated. However, Hoda et al.49 found that the mRNA expression of eNOS was dramatically increased in blood vessels after RIPerC during cerebral ischemia, concurrent with increased concentrations of nitric oxide in plasma. It is likely that RIPerC acts through multiple humoural mediators, and further investigation of nitric oxide related effects and novel mediators are required.

Future preclinical models should incorporate reperfusion to better model clinical realities. Increasingly, recanalization is achieved for ischemic stroke patients (particularly for proximal large vessel occlusions), but futile recanalization and the no-reflow phenomenon mean that clinical outcomes do not always match recanalization status. Notably, tissue level reperfusion is a better predictor of outcome than recanalization99. A major advantage of TPLSM is resolution of microvascular flow in the capillary bed that reflects tissue level perfusion, and future studies should incorporate transient proximal MCAO models and visualization of flow at the capillary level to better evaluate the efficacy of collateral therapeutics such as RIPerC to induce true reperfusion in ischemic regions.

Materials and methods

All procedures for collateral blood flow imaging in rats have been previously described16,17. Aged Male Sprague–Dawley rats (16–18 months of age) were used (sham treatment: n = 8; RIPerC: n = 9). Prior to experimental procedures, animals were housed in pairs on a 12-h day/night cycle and had access to food and water ad libitum. All procedures conformed to guidelines established by the Canadian Council on Animal Care and were approved by the University of Alberta Health Sciences Animal Care and Use Committee. Methodological and results reporting are consistent with the ARRIVE guidelines for preclinical research100. The experimental timeline is illustrated in Fig. 1a.

Anesthesia and monitoring

An induction chamber with 4–5% isoflurane (in 70% nitrogen and 30% oxygen) was used to induce light anaesthesia prior to intraperitoneal injections of urethane (i.p. 1.25 g/kg, divided into four doses delivered at 30-min intervals). Isoflurane was discontinued after the first urethane injection, and rats remained anaesthetized until euthanasia. Throughout the experiment, temperature was maintained at 36.5–37.5 °C with a thermostatically controlled warming pad. Pulse oximetry (MouseOx, STARR Life Sciences) was used to monitor heart rate, oxygen saturation, and breath rate.

Cranial window

LSCI and TPLSM were performed through craniotomy based cranial windows. These cranial windows allow for stable vascular imaging in rodents over hours to days101–104. After a midline incision, a 5 × 5 mm section of the skull over the distal regions of the right MCA territory was thinned using a dental drill until translucent (repeated flushes with saline are used to dissipate heat). The thinned bone was gently removed, and the dura matter reflected. The cranial window was then covered with a thin layer of 1.3% low melt agarose and sealed with a glass coverslip16,17,105.

dMCAO

A distal model of MCAO was used. To do so, bilateral common carotid artery (CCA) ligation was administered concurrent to ligation of a distal cortical branch of the MCA16,17. Distal MCA ligation and imaging protocols were performed by different individuals, and surgeons inducing ischemia were blind to the experimental group for each rat. CCAs were accessed through ventral midline cervical incisions and ligated below the carotid bifurcation (4–0 Prolene sutures). An incision over the right temporalis muscle was performed, and the muscle was gently separated from the bone. A dental drill was used to make a burr hole of 1.5 mm in diameter made through the squamosal bone. Dura was then removed and the exposed distal MCA was isolated with a loose square knot using an atraumatic 9–0 Prolene suture above the rhinal fissure. After pre-stroke imaging, the knot was ligated to induce permanent dMCAO.

LSCI

LSCI was used to create high spatial and temporal resolution maps of collateral blood flow on the cortical surface106,18,107,108. Rats were secured in ear bars on a custom-built stereotaxic plate under a Leica SP5 MP laser scanning microscope. The cortex was illuminated with a Thorlabs LDM 785S laser (20 mW, 785 nm) at approximately 30° incidence. 101 sequential images (1,024 × 1,024 pixels) were acquired at 20 Hz (5 ms exposure time) during each imaging time point. All processing and analysis of laser speckle images were performed using ImageJ software (NIH) by a blinded experimenter. Maps of speckle contrast were made by determining the speckle contrast factor K for each pixel in an image. K is the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean intensity (K = σs/I) in a small (5 × 5 pixels) region of the speckle image (26–28). Plots of K show maps of blood flow with darker vessels illustrating faster blood flow velocity. For quantification of penumbral flow, K was measured in a contiguous ROI consisting of an 800 × 800 pixel square positioned to include the distal MCA and ACA segments.

TPLSM

A Leica SP5 MP TPLSM and Coherent Chameleon Vision II pulse laser tuned to 800 nm was used for TPLSM in rats with blood plasma labelled with fluorescein isothiocyanate–dextran (70,000 MW, Sigma-Aldrich) injected (0.3 mL (5% (w/v) in saline, 0.2 mL supplements as required) via the tail vein16,17,104. Z-stacks through the first 0.15 mm of cortical tissue were acquired using a 10 × water dipping objective (Leica HCX APO L10 × /0.3 W). Vessel diameter measurements were made from maximum intensity projections of these stacks using an ImageJ plug-in (full-width at half-maximum algorithm)109. Diameter measurements were made along three distal segments of the MCA that included or were immediately adjacent anastomotic connections with the ACA (i.e. vessels that were predicted in pre-MCAO baseline imaging to exhibit retrograde flow from ACA to MCA territory after dMCAO). Red blood cell (RBC) velocity was determined using line scans along the lumen of these three arteriole segments over a length of approximately 100 pixels at scan rates of 1200 Hz. RBC velocity was determined from line scan images by calculating the slope of streaks104,102. Notably, while segments for analysis were selected prior to MCAO, all vessels included in our analyses demonstrated a reversal of flow direction confirming retrograde flow from ACA collaterals. Mean diameter and velocity measurements are illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. In each case, raw measurements are shown (Figs. 4a,5a) in addition to values normalized to Pre-MCAO baseline (Figs. 4b,5b and to Pre-RIPerC baseline (normalized to values at 60 min Post-MCAO, Figs. 4c,5c). Normalizations were performed within each vessel. That is, for each diameter or velocity measurement pertaining to an individual vessel, measurements at all time points following MCAO were divided by Pre-MCAO baseline measurement to better visualize changes in diameter or velocity due to stroke then treatment (Figs. 4b,5b). Similarly, raw measurements were also normalized relative to the final measurement prior to commencing RIPerC treatment (60 min Post-MCAO) to best visualize changes in diameter or velocity induced by treatment (Figs. 4c,5c). Normalizations were performed within each individual vessel then averaged within animals to provide a mean value for each animal. Finally, we calculated a measure of “Relative Flux” to provide an index in changes in overall flow due to treatment (Fig. 6a). RBC flux calculations provide an overall measure of flow through each vessel incorporating lumen diameter and flow velocity, and can be calculated using the following equation:

where v is the RBC velocity along the central axis of the vessel, and d is the vessel diameter. To calculate Relative Flux, we first calculated RBC flux for each vessel at all timepoints after the induction of dMCAO. The mean flux was then calculated for the period prior to treatment (the mean of Post-MCAO, 30 min, and 60 min Post-MCAO flux values), during RIPerC (mean of 90, 120, and 150 min Post-MCAO flux) and Post-RIPerC (180, 210, 240, and 270 min Post-MCAO flux). Figure 6a shows Relative Flux during and after RIPerC (i.e. mean values during these periods were normalized to the Pre-RIPerC values for each vessel, with the mean per animal plotted and used in statistics).

RIPerC via bilateral femoral occlusion (BFO)

BFO was performed as previously described17. Femoral arteries were dissected from accompanying veins and nerves below the groin ligaments. RIPerC was initiated 60-min after dMCAO by occluding and releasing the femoral arteries bilaterally with vascular clamps for 3 cycles (each occlusion or release lasted for 15 min). Control rats received a sham surgery with equivalent anesthesia and arterial isolation but did not receive BFO.

Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride staining

All rats were euthanized 6 h after induction of the dMCAO. The brains were rapidly removed and sliced into seven coronal, 2 mm sections using a brain matrix, then incubated in 2% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) solution at 37 °C for assessment of mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity. Tissue damage was assessed in digital images of TTC-stained tissue by a blinded experimenter using ImageJ (NIH) software. Volume of tissues showing early ischemic damage is expressed as a percentage of hemisphere. These measures were calculated for each tissue slice using the indirect method110,111 to control for tissue distortion due to edema using the following equation.

Volume of ischemic damage (%hemisphere) = [Σ(AC − ANI)/Σ(AC)] * 100.

where AC is the area of the hemisphere contralateral to stroke in a given tissue slice and ANI is the area of the non-injured tissue (i.e. non-ischemic tissue that stains red using TTC) in the ipsilateral (stroke affected) hemisphere of the same slice.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Graph Pad Prism (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA, US). After confirming a normal distribution using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, a mixed model two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Time and Treatment (RIPerC or Sham) as factors was used to evaluate LSCI measures (speckle contrast K) and TPLSM measures (vessel diameter, RBC velocity, and Relative Flux). Post hoc comparisons were performed using Holm–Sidak multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. A statistical trend was defined as P > 0.05 < 0.10. Volumes of ischemic tissue infarct (% of contralateral hemisphere) and physiological parameters (pulse, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation) between treatment groups were compared using an unpaired Student's t test. Sample sizes estimates were based on data from previous LSCI and TPLSM experiments in our laboratory16,17,105,18.

Ethics approval

University of Alberta Animal Care and Use Committee (AUP0000361).

Acknowledgements

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research supported by the Qatar National Research Fund (AS and IRW), Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (IRW), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (IRW), and Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (IRW). JM was supported by the Li Ka Shing Sino-Canadian Exchange Program.

Author contributions

JM, AS, and IRW designed the experiments. JM and YM conducted experiments. JM acquired and analyzed data. JM and IRW wrote the manuscript, with contributions from AS and YM.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ramakrishnan G, Armitage GA, Winship IR. Understanding and Augmenting Collateral Blood Flow During Ischemic Stroke. In: Julio César García R, editor. Acute Ischemic Stroke. InTech Open Access Publisher.

- 2.Winship IR. Cerebral collaterals and collateral therapeutics for acute ischemic stroke. Microcirculation (New York, NY: 1994) 2015;22(3):228–36. doi: 10.1111/micc.12177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung S, Wiest R, Gralla J, McKinley R, Mattle H, Liebeskind D. Relevance of the cerebral collateral circulation in ischaemic stroke: Time is brain, but collaterals set the pace. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017;147:w14538. doi: 10.4414/smw.2017.14538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liebeskind DS. Collateral lessons from recent acute ischemic stroke trials. Neurol. Res. 2014;36(5):397–402. doi: 10.1179/1743132814Y.0000000348;10.1179/1743132814Y.0000000348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liebeskind DS. Collateral circulation. Stroke J. Cereb. Circ. 2003;34(9):2279–2284. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000086465.41263.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shuaib A, Butcher K, Mohammad AA, Saqqur M, Liebeskind DS. Collateral blood vessels in acute ischaemic stroke: A potential therapeutic target. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(10):909–921. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bang OY, Saver JL, Buck BH, Alger JR, Starkman S, Ovbiagele B, et al. Impact of collateral flow on tissue fate in acute ischaemic stroke. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2008;79(6):625–629. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.132100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bang OY, Saver JL, Kim SJ, Kim GM, Chung CS, Ovbiagele B, et al. Collateral flow predicts response to endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke J. Cereb. Circ. 2011;42(3):693–699. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595256;10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faber JE, Zhang H, Lassance-Soares RM, Prabhakar P, Najafi AH, Burnett MS, et al. Aging causes collateral rarefaction and increased severity of ischemic injury in multiple tissues. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011;31(8):1748–1756. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.227314;10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.227314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piedade GS, Schirmer CM, Goren O, Zhang H, Aghajanian A, Faber JE, et al. Cerebral collateral circulation: A review in the context of ischemic stroke and mechanical thrombectomy. World Neurosurg. 2019;122:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang H, Faber JE. Transient versus permanent MCA occlusion in mice genetically modified to have good versus poor collaterals. Med One. 2019 doi: 10.20900/mo.20190024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang H, Prabhakar P, Sealock R, Faber JE. Wide genetic variation in the native pial collateral circulation is a major determinant of variation in severity of stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metabol. 2010;30(5):923–934. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.10;10.1038/jcbfm.2010.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menon BK, O'Brien B, Bivard A, Spratt NJ, Demchuk AM, Miteff F, et al. Assessment of leptomeningeal collaterals using dynamic CT angiography in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(3):365–371. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.171;10.1038/jcbfm.2012.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brozici M, van der Zwan A, Hillen B. Anatomy and functionality of leptomeningeal anastomoses: A review. Stroke J. Cereb. Circ. 2003;34(11):2750–2762. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000095791.85737.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendrikse J, van Raamt AF, van der Graaf Y, Mali WP, van der Grond J. Distribution of cerebral blood flow in the circle of Willis. Radiology. 2005;235(1):184–189. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2351031799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma J, Ma Y, Shuaib A, Winship IR. Impaired collateral flow in pial arterioles of aged rats during ischemic stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s12975-019-00710-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma J, Ma Y, Dong B, Bandet MV, Shuaib A, Winship IR. Prevention of the collapse of pial collaterals by remote ischemic perconditioning during acute ischemic stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37(8):3001–3014. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16680636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armitage GA, Todd KG, Shuaib A, Winship IR. Laser speckle contrast imaging of collateral blood flow during acute ischemic stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(8):1432–1436. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nie X, Pu Y, Zhang Z, Liu X, Duan W, Liu L. Futile Recanalization after Endovascular Therapy in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:5879548. doi: 10.1155/2018/5879548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lima FO, Furie KL, Silva GS, Lev MH, Camargo EC, Singhal AB, et al. The pattern of leptomeningeal collaterals on CT angiography is a strong predictor of long-term functional outcome in stroke patients with large vessel intracranial occlusion. Stroke J. Cereb. Circ. 2010;41(10):2316–2322. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.592303;10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.592303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z, Luo W, Zhou F, Li P, Luo Q. Dynamic change of collateral flow varying with distribution of regional blood flow in acute ischemic rat cortex. J Biomed Opt. 2012;17(12):125001. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.12.125001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hussein HM, Saleem MA, Qureshi AI. Rates and predictors of futile recanalization in patients undergoing endovascular treatment in a multicenter clinical trial. Neuroradiology. 2018;60(5):557–563. doi: 10.1007/s00234-018-2016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Psychogios MN, Schramm P, Frolich AM, Kallenberg K, Wasser K, Reinhardt L, et al. Alberta stroke program early CT scale evaluation of multimodal computed tomography in predicting clinical outcomes of stroke patients treated with aspiration thrombectomy. Stroke. 2013;44(8):2188–2193. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hussein HM, Georgiadis AL, Vazquez G, Miley JT, Memon MZ, Mohammad YM, et al. Occurrence and predictors of futile recanalization following endovascular treatment among patients with acute ischemic stroke: A multicenter study. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol.. 2010;31(3):454–458. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2006;10.3174/ajnr.A2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lansberg MG, Bluhmki E, Thijs VN. Efficacy and safety of tissue plasminogen activator 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke: A metaanalysis. Stroke J. Cereb. Circ. 2009;40(7):2438–41. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.552547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark WM, Wissman S, Albers GW, Jhamandas JH, Madden KP, Hamilton S. Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (Alteplase) for ischemic stroke 3 to 5 hours after symptom onset. The ATLANTIS Study: A randomized controlled trial. Alteplase thrombolysis for acute noninterventional therapy in ischemic stroke. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1999;282(21):2019–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.21.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, von Kummer R, Davalos A, Meier D, et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet. 1998;352(9136):1245–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke The national institute of neurological disorders and stroke rt-PA stroke Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333(24):1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaur J, Zhao Z, Klein GM, Lo EH, Buchan AM. The neurotoxicity of tissue plasminogen activator? J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24(9):945–963. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000137868.50767.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wannamaker R, Guinand T, Menon BK, Demchuk A, Goyal M, Frei D, et al. Computed tomographic perfusion predicts poor outcomes in a randomized trial of endovascular therapy. Stroke. 2018;49(6):1426–1433. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.019806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, Dippel DW, Mitchell PJ, Demchuk AM, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387(10029):1723–1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, Eesa M, Rempel JL, Thornton J, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desai SM, Rocha M, Molyneaux BJ, Starr M, Kenmuir CL, Gross BA, et al. Thrombectomy 6–24 hours after stroke in trial ineligible patients. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2018 doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-013915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ragoschke-Schumm A, Walter S. DAWN and DEFUSE-3 trials: Is time still important? Radiologe. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s00117-018-0406-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheinberg DL, McCarthy DJ, Peterson EC, Starke RM. DEFUSE-3 trial: Reinforcing evidence for extended endovascular intervention time window for ischemic stroke. World Neurosurg. 2018;112:275–276. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, Christensen S, Tsai JP, Ortega-Gutierrez S, et al. Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378(8):708–718. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Albers GW, Lansberg MG, Kemp S, Tsai JP, Lavori P, Christensen S, et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial of endovascular therapy following imaging evaluation for ischemic stroke (DEFUSE 3) Int. J. Stroke. 2017;12(8):896–905. doi: 10.1177/1747493017701147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mundiyanapurath S, Diatschuk S, Loebel S, Pfaff J, Pham M, Mohlenbruch MA, et al. Outcome of patients with proximal vessel occlusion of the anterior circulation and DWI–PWI mismatch is time-dependent. Eur. J. Radiol. 2017;91:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Desai SM, Haussen DC, Aghaebrahim A, Al-Bayati AR, Santos R, Nogueira RG, et al. Thrombectomy 24 hours after stroke: Beyond DAWN. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2018 doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-013923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ducroux C, Khoury N, Lecler A, Blanc R, Chetrit A, Redjem H, et al. Application of the DAWN clinical imaging mismatch and DEFUSE 3 selection criteria: Benefit seems similar but restrictive volume cut-offs might omit potential responders. Eur. J. Neurol. 2018 doi: 10.1111/ene.13660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee KJ, Kim BJ, Kim DE, Ryu WS, Han MK, Kim JT, et al. Nationwide estimation of eligibility for endovascular thrombectomy based on the DAWN trial. J. Stroke. 2018;20(2):277–279. doi: 10.5853/jos.2018.00836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alberts MJ, Shang T, Magadan A. Endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke: Dawn of a new era. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(10):1101–1103. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bang OY, Saver JL, Kim SJ, Kim GM, Chung CS, Ovbiagele B, et al. Collateral flow averts hemorrhagic transformation after endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke J. Cereb. Circ. 2011;42(8):2235–2239. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604603;10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christoforidis GA, Karakasis C, Mohammad Y, Caragine LP, Yang M, Slivka AP. Predictors of hemorrhage following intra-arterial thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke: The role of pial collateral formation. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2009;30(1):165–170. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1276;10.3174/ajnr.A1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaibhav K, Braun M, Khan MB, Fatima S, Saad N, Shankar A, et al. Remote ischemic post-conditioning promotes hematoma resolution via AMPK-dependent immune regulation. J. Exp. Med. 2018;215(10):2636–2654. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hess DC, Hoda MN, Khan MB. Humoral mediators of remote ischemic conditioning: Important role of eNOS/NO/nitrite. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2016;121:45–48. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18497-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hess DC, Blauenfeldt RA, Andersen G, Hougaard KD, Hoda MN, Ding Y, et al. Remote ischaemic conditioning-a new paradigm of self-protection in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015;11(12):698–710. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan J, Li X, Peng Y. Remote ischemic conditioning for acute ischemic stroke: Dawn in the darkness. Rev Neurosci. 2016;27(5):501–510. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2015-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoda MN, Siddiqui S, Herberg S, Periyasamy-Thandavan S, Bhatia K, Hafez SS, et al. Remote ischemic perconditioning is effective alone and in combination with intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator in murine model of embolic stroke. Stroke. 2012;43(10):2794–2799. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.660373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Menon BK, Smith EE, Coutts SB, Welsh DG, Faber JE, Goyal M, et al. Leptomeningeal collaterals are associated with modifiable metabolic risk factors. Ann. Neurol. 2013;74(2):241–248. doi: 10.1002/ana.23906;10.1002/ana.23906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strandgaard S. Cerebral blood flow in the elderly: Impact of hypertension and antihypertensive treatment. Cardiovasc. Drugs. Ther. 1991;4(Suppl 6):1217–1221. doi: 10.1007/bf00114223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ay H, Koroshetz WJ, Vangel M, Benner T, Melinosky C, Zhu M, et al. Conversion of ischemic brain tissue into infarction increases with age. Stroke. 2005;36(12):2632–2636. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000189991.23918.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J, Peng X, Lassance-Soares RM, Najafi AH, Alderman LO, Sood S, et al. Aging-induced collateral dysfunction: Impaired responsiveness of collaterals and susceptibility to apoptosis via dysfunctional eNOS signaling. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2011;4(6):779–789. doi: 10.1007/s12265-011-9280-4;10.1007/s12265-011-9280-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heinen A, Behmenburg F, Aytulun A, Dierkes M, Zerbin L, Kaisers W, et al. The release of cardioprotective humoral factors after remote ischemic preconditioning in humans is age- and sex-dependent. J Transl Med. 2018;16(1):112. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1480-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shih AY, Friedman B, Drew PJ, Tsai PS, Lyden PD, Kleinfeld D. Active dilation of penetrating arterioles restores red blood cell flux to penumbral neocortex after focal stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metabol. 2009;29(4):738–751. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang JY, Li LT, Wang H, Liu SS, Lu YM, Liao MH, et al. In vivo two-photon fluorescence microscopy reveals disturbed cerebral capillary blood flow and increased susceptibility to ischemic insults in diabetic mice. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2014;20(9):816–822. doi: 10.1111/cns.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Espinosa de Rueda M, Parrilla G, Manzano-Fernandez S, Garcia-Villalba B, Zamarro J, Hernandez-Fernandez F, et al. Combined multimodal computed tomography score correlates with futile recanalization after thrombectomy in patients with acute stroke. Stroke. 2015;46(9):2517–22. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baron JC. Protecting the ischaemic penumbra as an adjunct to thrombectomy for acute stroke. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018;14(6):325–337. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoda MN, Bhatia K, Hafez SS, Johnson MH, Siddiqui S, Ergul A, et al. Remote ischemic perconditioning is effective after embolic stroke in ovariectomized female mice. Transl. Stroke Res. 2014;5(4):484–490. doi: 10.1007/s12975-013-0318-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shaul ME, Hallacoglu B, Sassaroli A, Shukitt-Hale B, Fantini S, Rosenberg IH, et al. Cerebral blood volume and vasodilation are independently diminished by aging and hypertension: A near infrared spectroscopy study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(Suppl 3):S189–S198. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sonntag WE, Lynch CD, Cooney PT, Hutchins PM. Decreases in cerebral microvasculature with age are associated with the decline in growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1. Endocrinology. 1997;138(8):3515–3520. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.8.5330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilkinson JH, Hopewell JW, Reinhold HS. A quantitative study of age-related changes in the vascular architecture of the rat cerebral cortex. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1981;7(6):451–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1981.tb00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Knox CA, Oliveira A. Brain aging in normotensive and hypertensive strains of rats. III. A quantitative study of cerebrovasculature. Acta Neuropathol. 1980;52(1):17–25. doi: 10.1007/bf00687224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Farkas E, de Vos RA, Donka G, Jansen Steur EN, Mihaly A, Luiten PG. Age-related microvascular degeneration in the human cerebral periventricular white matter. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;111(2):150–157. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-0007-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Farkas E, Luiten PG. Cerebral microvascular pathology in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;64(6):575–611. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu X, Wang B, Ren C, Hu J, Greenberg DA, Chen T, et al. Age-related impairment of vascular structure and functions. Aging Dis. 2017;8(5):590–610. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hunter JM, Kwan J, Malek-Ahmadi M, Maarouf CL, Kokjohn TA, Belden C, et al. Morphological and pathological evolution of the brain microcirculation in aging and Alzheimer's disease. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e36893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Villena A, Vidal L, Diaz F, Perez De Vargas I. Stereological changes in the capillary network of the aging dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2003;274(1):857–61. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thore CR, Anstrom JA, Moody DM, Challa VR, Marion MC, Brown WR. Morphometric analysis of arteriolar tortuosity in human cerebral white matter of preterm, young, and aged subjects. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66(5):337–345. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e3180537147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brown WR, Moody DM, Challa VR, Thore CR, Anstrom JA. Venous collagenosis and arteriolar tortuosity in leukoaraiosis. J Neurol Sci. 2002;203–204:159–163. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arsava EM, Vural A, Akpinar E, Gocmen R, Akcalar S, Oguz KK, et al. The detrimental effect of aging on leptomeningeal collaterals in ischemic stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2014;23(3):421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rzechorzek W, Zhang H, Buckley BK, Hua K, Pomp D, Faber JE. Aerobic exercise prevents rarefaction of pial collaterals and increased stroke severity that occur with aging. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37(11):3544–3555. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17718966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Leoni RF, Oliveira IA, Pontes-Neto OM, Santos AC, Leite JP. Cerebral blood flow and vasoreactivity in aging: An arterial spin labeling study. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2017;50(4):e5670. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20175670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wagner M, Jurcoane A, Volz S, Magerkurth J, Zanella FE, Neumann-Haefelin T, et al. Age-related changes of cerebral autoregulation: New insights with quantitative T2'-mapping and pulsed arterial spin-labeling MR imaging. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2012;33(11):2081–2087. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Behnke BJ, Delp MD. Aging blunts the dynamics of vasodilation in isolated skeletal muscle resistance vessels. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010;108(1):14–20. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00970.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prisby RD, Ramsey MW, Behnke BJ, Dominguez JM, 2nd, Donato AJ, Allen MR, et al. Aging reduces skeletal blood flow, endothelium-dependent vasodilation, and NO bioavailability in rats. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2007;22(8):1280–1288. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fisher M, Feuerstein G, Howells DW, Hurn PD, Kent TA, Savitz SI, et al. Update of the stroke therapy academic industry roundtable preclinical recommendations. Stroke J. Cereb. Circ. 2009;40(6):2244–2250. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.541128;10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.541128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fisher M. Stroke therapy academic industry R. Recommendations for advancing development of acute stroke therapies: Stroke therapy academic industry roundtable 3. Stroke J. Cereb. Circ. 2003;34(6):1539–46. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000072983.64326.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhu J, Hancock AM, Qi L, Telkmann K, Shahbaba B, Chen Z, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of pial collateral blood flow following permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in a rat model of sensory-based protection: A Doppler optical coherence tomography study. Neurophotonics. 2019;6(4):045012. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.6.4.045012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gonzalez NR, Hamilton R, Bilgin-Freiert A, Dusick J, Vespa P, Hu X, et al. Cerebral hemodynamic and metabolic effects of remote ischemic preconditioning in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2013;115:193–198. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-1192-5_36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hougaard KD, Hjort N, Zeidler D, Sorensen L, Norgaard A, Hansen TM, et al. Remote ischemic perconditioning as an adjunct therapy to thrombolysis in patients with acute ischemic stroke: A randomized trial. Stroke. 2014;45(1):159–167. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hougaard KD, Hjort N, Zeidler D, Sorensen L, Norgaard A, Thomsen RB, et al. Remote ischemic perconditioning in thrombolysed stroke patients: Randomized study of activating endogenous neuroprotection—Design and MRI measurements. Int. J. Stroke. 2013;8(2):141–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhao W, Li S, Ren C, Meng R, Jin K, Ji X. Remote ischemic conditioning for stroke: Clinical data, challenges, and future directions. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2019;6(1):186–196. doi: 10.1002/acn3.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhao W, Che R, Li S, Ren C, Li C, Wu C, et al. Remote ischemic conditioning for acute stroke patients treated with thrombectomy. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2018;5(7):850–856. doi: 10.1002/acn3.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Drew PJ, Shih AY, Driscoll JD, Knutsen PM, Blinder P, Davalos D, et al. Chronic optical access through a polished and reinforced thinned skull. Nat. Methods. 2010;7(12):981–984. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Murtha LA, Beard DJ, Bourke JT, Pepperall D, McLeod DD, Spratt NJ. Intracranial pressure elevation 24 h after ischemic stroke in aged rats is prevented by early, short hypothermia treatment. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:124. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beard DJ, Murtha LA, McLeod DD, Spratt NJ. Intracranial pressure and collateral blood flow. Stroke. 2016;47(6):1695–1700. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Beard DJ, Logan CL, McLeod DD, Hood RJ, Pepperall D, Murtha LA, et al. Ischemic penumbra as a trigger for intracranial pressure rise—A potential cause for collateral failure and infarct progression? J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36(5):917–927. doi: 10.1177/0271678X15625578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Murtha LA, McLeod DD, Pepperall D, McCann SK, Beard DJ, Tomkins AJ, et al. Intracranial pressure elevation after ischemic stroke in rats: Cerebral edema is not the only cause, and short-duration mild hypothermia is a highly effective preventive therapy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35(12):2109. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Beard DJ, McLeod DD, Logan CL, Murtha LA, Imtiaz MS, van Helden DF, et al. Intracranial pressure elevation reduces flow through collateral vessels and the penetrating arterioles they supply. A possible explanation for 'collateral failure' and infarct expansion after ischemic stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35(5):861–72. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Abu-Amara M, Yang SY, Seifalian A, Davidson B, Fuller B. The nitric oxide pathway—Evidence and mechanisms for protection against liver ischaemia reperfusion injury. Liver Int. 2012;32(4):531–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2012.02755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Abu-Amara M, Yang SY, Quaglia A, Rowley P, Fuller B, Seifalian A, et al. Role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in remote ischemic preconditioning of the mouse liver. Liver Transpl. 2011;17(5):610–619. doi: 10.1002/lt.22272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Abu-Amara M, Yang SY, Quaglia A, Rowley P, de Mel A, Tapuria N, et al. Nitric oxide is an essential mediator of the protective effects of remote ischaemic preconditioning in a mouse model of liver ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2011;121(6):257–266. doi: 10.1042/CS20100598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Totzeck M, Hendgen-Cotta UB, Rassaf T. Nitrite–nitric oxide signaling and cardioprotection. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017;982:335–346. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-55330-6_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rassaf T, Totzeck M, Hendgen-Cotta UB, Shiva S, Heusch G, Kelm M. Circulating nitrite contributes to cardioprotection by remote ischemic preconditioning. Circ. Res. 2014;114(10):1601–1610. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shiva S. Nitrite: a physiological store of nitric oxide and modulator of mitochondrial function. Redox Biol. 2013;1(1):40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Qazi MA, Rizzatti F, Piknova B, Sibmooh N, Stroncek DF, Schechter AN. Effect of storage levels of nitric oxide derivatives in blood components. F1000Res. 2012;1:35. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.1-35.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E. NO generation from nitrite and its role in vascular control. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005;25(5):915–922. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000161048.72004.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cho TH, Nighoghossian N, Mikkelsen IK, Derex L, Hermier M, Pedraza S, et al. Reperfusion within 6 hours outperforms recanalization in predicting penumbra salvage, lesion growth, final infarct, and clinical outcome. Stroke. 2015;46(6):1582–1589. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: The ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2012;20(4):256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Koletar MM, Dorr A, Brown ME, McLaurin J, Stefanovic B. Refinement of a chronic cranial window implant in the rat for longitudinal in vivo two-photon fluorescence microscopy of neurovascular function. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):5499. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41966-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tennant KA, Brown CE. Diabetes augments in vivo microvascular blood flow dynamics after stroke. J Neurosci. 2013;33(49):19194–19204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3513-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Weilinger NL, Lohman AW, Rakai BD, Ma EM, Bialecki J, Maslieieva V, et al. Metabotropic NMDA receptor signaling couples Src family kinases to pannexin-1 during excitotoxicity. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19(3):432–442. doi: 10.1038/nn.4236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shih AY, Driscoll JD, Drew PJ, Nishimura N, Schaffer CB, Kleinfeld D. Two-photon microscopy as a tool to study blood flow and neurovascular coupling in the rodent brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metabol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.196;10.1038/jcbfm.2011.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Winship IR, Armitage GA, Ramakrishnan G, Dong B, Todd KG, Shuaib A. Augmenting collateral blood flow during ischemic stroke via transient aortic occlusion. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metabol. 2014;34(1):61–71. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.162;10.1038/jcbfm.2013.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Winship IR. Laser speckle contrast imaging to measure changes in cerebral blood flow. Methods Mol. Biol. (Clifton, NJ). 2014;1135:223–235. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0320-7_19;10.1007/978-1-4939-0320-7_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Boas DA, Dunn AK. Laser speckle contrast imaging in biomedical optics. J. Biomed. Opt. 2010;15(1):011109. doi: 10.1117/1.3285504;10.1117/1.3285504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Strong AJ, Bezzina EL, Anderson PJ, Boutelle MG, Hopwood SE, Dunn AK. Evaluation of laser speckle flowmetry for imaging cortical perfusion in experimental stroke studies: Quantitation of perfusion and detection of peri-infarct depolarisations. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metabol. 2006;26(5):645–653. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fischer MJ, Uchida S, Messlinger K. Measurement of meningeal blood vessel diameter in vivo with a plug-in for ImageJ. Microvasc. Res. 2010;80(2):258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.04.004;10.1016/j.mvr.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lin TN, He YY, Wu G, Khan M, Hsu CY. Effect of brain edema on infarct volume in a focal cerebral ischemia model in rats. Stroke. 1993;24(1):117–121. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Swanson RA, Morton MT, Tsao-Wu G, Savalos RA, Davidson C, Sharp FR. A semiautomated method for measuring brain infarct volume. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10(2):290–293. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]