Abstract

Getting men to be actively involved in Antenatal Care (ANC) has been acknowledged by the World Health Organisation as a key indicator for better maternal health outcomes. We investigated the perception of women about barriers to male involvement in ANC in Sekondi, Ghana. Dwelling on cross-sectional design, we used a sample of 300 pregnant women (adolescents excluded) who had ever attended ANC in five fishing communities in Sekondi. The study was underpinned by a conceptual framework adapted from Doe's conceptual framework of male partner involvement in maternity care. We used questionnaire for the data collection. Both descriptive-frequencies and percentages; and inferential-binary logistic regression analyses were carried out. Seven out of ten (70%) participants indicated high male involvement in ANC. Respondents whose partners were aged 50–59 were less likely to report high male involvement in ANC compared to those whose partners were aged 20–29 years (OR = 0.47, 95% CI = [0.35–0.86], p = 0.03). Those living together with their partners were about two times more likely to report high male involvement in ANC compared to those who did not live with their partners (OR = 1.63, 95% CI = [1.18–3.19], p = 0.01). Participants who identified long waiting time at the health facility as a determinant of male involvement in ANC were less likely to report high male involvement in ANC compared to those who disagreed (OR = 0.57, 95% CI = [0.38–0.85], p = 0.01). The outcome of our study calls for male partner friendly policy driven environment at the various ANC visit points that would make men more comfortable to accompany their partners in accessing ANC services.

Keywords: Perception, Sekondi, Ghana, Male involvement, Antenatal care, Education, Health sciences, Public health, Quality of life, Sociology, Women's health

Perception; Sekondi; Ghana; Male involvement; Antenatal care, Education; Health sciences; Public health; Quality of life; Sociology; Women's health.

1. Introduction

Complications during pregnancy is a major public health issue in low- and middle-income countries [1]. Globally, 303,000 women died in 2015 due to pregnancy related complications. Out of this, 99% occurred in low and middle-income countries and the highest burden is in Africa [2]. As a result of these, maternal and child health were part of the Millennium Development Goals and continue to be on the global agenda found in the Sustainable Development Goals [3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests a focused ANC model to ensure improvement in maternal health. One of these focused models for promoting the health of women and children is to support male involvement in maternal health care [4]. Evidence from an interventional study in African countries suggest that the three exposure indexes consistently and significantly associated with women's use of Skilled Birth Attendants (SBAs) are husband's involvement in decision-making, couple's discussion and planning within the household, and having received counselling on birth preparedness during ANC [5].

In many low-and middle-income countries such as Ghana, maternal mortality rates continue to be high with most cases occurring from pregnancy related complications and childbirth [6, 7]. Many women, especially those in the low-and middle-income and resource constraint settings are highly susceptible to pregnancy and delivery induced adverse fetomaternal consequences [8]. Attaining the minimum recommended antenatal care (ANC) visits have been acknowledged by the WHO as a protective factor for successful childbirth experience. ANC is the regular medical and nursing care recommended for women during pregnancy, with the goal of providing regular check-ups that allow doctors or midwives to prevent, detect and treat potential health problems that may arise prior to delivery [9]. Considering the proven benefits of ANC [10], the 2016 “WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience” recommends eight visits for women in low-and middle-income countries instead of four as earlier recommended by the Guidelines Development Group (GDG) [2].

Under the 2016 WHO ANC model, “visit” is substituted with “contact” signifying the need for active interpersonal relationship between the expectant mother and the healthcare providera right step to accelerate the attainment of 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births as envisioned by the third SDG [3]. Attaining the recommended “contact” will require immense partner/male support especially in the case of Ghana where men are predominantly breadwinners, household heads and decision makers [11, 12] The new 2016 ANC recommendations also highlight the need for interventions that can promote male involvement during pregnancy, intrapartum and the entire postpartum period. Globally, low male involvement in maternal health care services remains a problem to health care providers and policy makers [13]. Getting men as active contributors of ANC and the entire continuum of maternal care symbolizes birth preparedness and complication readiness on the part of both partners. When effective interventions are instituted to have men accompanying their partners to ANC, they will benefit from the information delivered during counselling sessions and therefore appreciate the need to create a conducive psychological, stress free and conducive environment for women throughout the season. It will also offer opportunity to the health workers to educate men about early recognition of obstetric emergency in order to make appropriate decisions and act in a timely fashion to ensure positive obstetric outcome [14].

Male involvement in ANC has been described as a process of social and behavioural change that is needed for them to play more responsible roles in maternal health care with the purpose of ensuring women and children's wellbeing [15]. Low male involvement in maternal health care services results in low utilization of ANC, health facility delivery and postnatal care leading to increased tendency of maternal morbidity and mortality [16]. Men accompanying their wives to ANC and other maternal health services is an important factor contributing to the reduction of maternal morbidity and mortality [17] by increasing chances of skilled birth attendance [5]. According to Hou and Ma [18], men can positively affect the prevention of maternal and child mortality by being able to recognize an obstetric emergency, initiate the decision to seek care and transport pregnant women to obtain health services. The prospects of getting men to be active with ANC is a function of women's perception about the need for them to be accompanied by their partners. Women have a key role to play because it is only when they are fully convinced about the need to have their partners' company for ANC that they will think of how best to communicate with their partners in that regard [19].

In the Ghanaian socio-cultural setting, men exert a lot of power in decision making in the home and play a vital role in the health seeking behaviour of women [11]. Funding and permission to seek maternity care including antenatal care often rest with the male partner. Male partner involvement in maternal care is perceived to be low and partly accounts for the slow pace of the decline in maternal mortalities [20]. Various factors could affect or determine male partner involvement in ANC. These include sociodemographic factors, cultural factors and health facility factors. In Ghana, it appears not much work has been done on male involvement in maternal care, particularly antenatal care. Findings of studies by Mitchell [21], Doe [20], Sham-Una [22] and Craymah, Oppong and Tuoyire [16] conducted in Nkwanta South District, Ablekuma South District, Kumasi Metropolis and Anomabo in Ghana respectively show that male involvement in antenatal care is still a problem. Most of these studies have mainly focused on partners of pregnant women [16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22] neglecting the views of the pregnant women themselves. This calls for the need to find out the perception of women on the barriers to male involvement in antenatal care in Sekondi, Ghana.

1.1. Conceptual framework

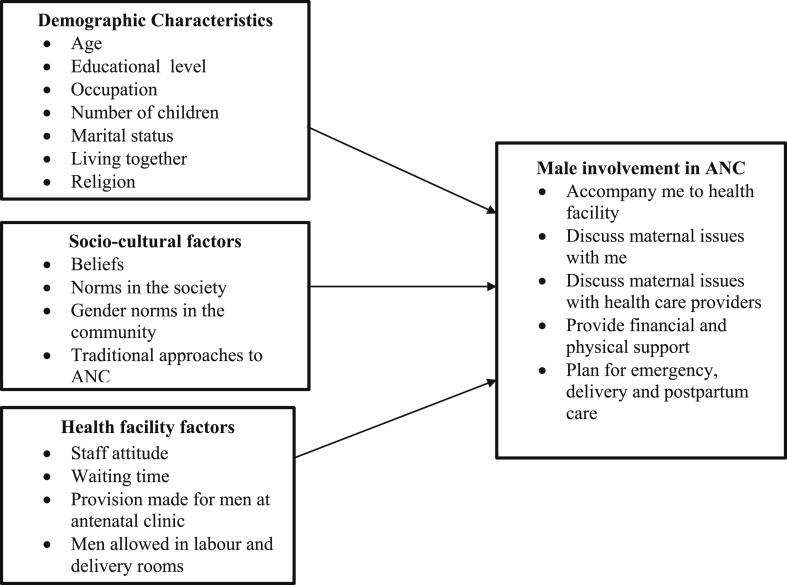

The conceptual framework for the study was adapted from Doe [20] conceptual framework of male partner involvement in maternity care. In the adapted model, a man's involvement in the ANC of his partner may be affected by his socio-demographic characteristics like age, educational level, occupation and religion. Marital status and whether or not they live together may also be important factors in determining the level of involvement. Cultural norms that segregate gender roles may not encourage men to take part in activities that are tagged as feminine. Other family members like mothers and mothers-in-law may be seen as the ones responsible for issues related to pregnancy and delivery and so men may be reluctant to get involved. Some taboos may prohibit male involvement in some aspects of maternity care. Factors within the health facility may or may not encourage male involvement in maternity care. Health facilities' readiness to accommodate men who accompany their partners, male friendliness of the services may influence male involvement.

The model is applicable to the study in the sense that, its underlying argument best explains the present study's focus of investigating women's perception about the factors associated with male involvement in ANC in Sekondi. Guided by the framework, the study will be able to find out women's perception regarding the major barriers to ANC. As prescribed by the conceptual framework, age, educational level, occupation, number of children, marital status, living together and religion will be considered as the socio-demographic characteristics of males that could influence their involvement in ANC. The socio-cultural factors considered in the study as influencing male involvement in ANC are beliefs, norm in the society, gender norms in the community and traditional approaches to ANC. The health facility factors associated with ANC in the study are staff attitude, waiting time, provision made for men at antenatal clinic and men allowed in labour wards during delivery. The outcome variable (male involvement in ANC) was measured by five main variables. The variables are accompanying partner to health facility, discussing maternal health issues with partner, providing financial and physical support for partner and planning for emergency, delivery and postpartum care (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Barriers to male involvement in ANC [20].

2. Methods

2.1. Study setting

The study was conducted at Sekondi, in the Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis of the Western region of Ghana. Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis is located at the south-eastern part of the Western Region. The Metropolis is bordered to the west by Ahanta West District and to the east by Shama District. At the south of the Metropolis is the Atlantic Ocean and at the northern part is Wassa East District. The Metropolis covers land size of 191.7 km2 and Sekondi-Takoradi is the regional administrative capital. The total number of persons in the metropolis is 559,548. The population among urban and rural localities are 35,790 (96.1%) and 37,020 (3.9%) respectively. Majority of the population in the Metropolis are concentrated in the young age group 0–24 years (55.2%). The proportion of persons less than 15 years (32.65%) is larger than the proportion (29.41%) in 30–59 age groups. The percentage of females (29.64%) in age group 30–59 is slightly higher than that of males (29.17%). The Total Fertility Rate is 2.8 per woman, and the General Fertility Rate is 69.4 per 1000 live births while the crude birth rate is 23.3 per 1000 live births [23].

2.2. Research design

Cross-sectional research design was used for the study. The design was well thought-out to be appropriate for this study because it is suitable for obtaining information concerning current status of the phenomena under study and to describe “what” exists with respect to variables or conditions in a situation [24].

2.3. Population

The population for the study was 22,382. To arrive at this population, 4% of the total population of the Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis, which according to Orish et al. [25] constitute the total number of pregnant women in the Metropolis was derived from a total population of 559,548 [23]. Out of this population, 9.5% were between then ages 20–49 which constitute 2,126 of the entire population of the study. The population involved women in selected fishing communities in Sekondi who were pregnant at the time of the study and made at least one ANC visit in the course of their pregnancy. The communities were Nkotompo, Egyamuabakam, Ekuasi, Essaman and Sekondi Beach side. The choice of the fishing communities was influenced by the fact that fertility levels in fishing communities have been found to be high [26, 27]). The study focused on pregnant women in their reproductive age but excluded adolescents (15–19 years) The adolescents were excluded because few of such adolescents have partners who might accompany them to ANC clinics [28, 29].

2.4. Sampling procedure

The actual sample size for the study was 328, obtained from Krejcie and Morgan [30] table for determining sample size. However, a response rate of 91% was achieved which translated into a sample size of 300. Accidental sampling was used to sample the research participants from various fishing communities within Sekondi. Using this technique, individuals who were part of the population and available at the time of data collection were recruited for the study. Some of the participants were sampled from the seashore and others from homes within the communities in Sekondi. To ensure the eligibility of the participants, they were asked of their age to ensure that they fall within the required age group and were also asked if they had ever attended ANC.

2.5. Data collection instrument

Questionnaire was used for collecting data from the research participants. For further details, see Instrument_MI copy.docx. Questionnaire was used because it is the most commonly used instrument in survey research and it is used to collect information about people's views, opinions, impressions, feelings and behaviours [31]. The questionnaire was made up of five main sections (A, B, C, D and E). Section A focused on participants' socio-demographic characteristics which included age, marital status, educational level, occupation, religion, number of children and living arrangement.

Section B touched on the level of male involvement in ANC. Some of the items included partner involvement in the decision on where to attend ANC, partner accompanying participant to ANC Clinic, partner discussing the outcome of ANC visits with participant, partner proving funds for participant's ANC visits, partner informing participant to go for ANC visits, partner discussing health issues relating to the pregnancy with participant's health care providers and partner talking to participant always about her pregnancy.

Section C focused on the socio-demographic barriers to male involvement in ANC. Items under this section were age of partner, marital status of partner, educational level of partner, occupation of partner, religion of partner, number of children of partner and living arrangement of partner. Section D was on the socio-cultural barriers to male involvement in ANC. The items under the section included; ridicule from friends does not allow him to accompany me for ANC, it is unacceptable for a man to carry out household chores for the wife when she is pregnant; in our culture, men are prohibited from escorting their wives for ANC; even if a woman is pregnant, she still has to perform her normal duties in the home and my partner will be seen as being controlled by me if he escorts me to ANC.

Section E was on the healthcare environment factors which might serve as barriers to male involvement in ANC. Some of the items included cost of health care, long waiting time, ridicule from health workers, partner non-involvement in ANC services, lack of space to accommodate partner and distance to health facilities. Apart from the socio-demographic characteristics of participants, questions on the barriers to male involvement in ANC were obtained from previous studies related to the current study [20, 21, 22]. To ensure validity of the instrument, it was tested through construct validity, face validity and content validity. With face validity, the instrument was developed based on literature on barriers to male involvement in antenatal care, focusing on the main findings of previous studies. Face and content validity were determined through inspection by experts in maternal health. After concluding on the face and content validity, the questionnaire was pre-tested with pregnant women at Bakano in the Cape Coast Metropolis of the Central Region of Ghana. This was done to validate the instrument by verifying the viability of the data collection and analysis and to strengthen the instrument by identifying and correcting inherent lapses. Kuder-Richardson formula (KR-21) was used to calculate the internal consistency reliability coefficient of the items on level of male involvement in ANC, socio-cultural and health facility factors and the values were 0.72, 0.71 and 0.75 respectively.

2.6. Ethical approval and data collection procedures

Before the data collection, the proposal with the instrument were submitted to the Ethical Review Board of the University of Cape Coast for approval (ID: UCCIRB/A/2016/122). After the review, an introductory letter detailing the purpose and implications of the study was sent to the chiefs of the participating communities. When permission was granted by the chiefs, date for data collection was set for each community. One week was used to collect data from the respondents. The data collection started on the 15th of May 2017 and ended on the 22nd of May 2017. Items on the questionnaire were read to some of the respondents while other respondents completed the questionnaire on their own-depending on literacy competence in the English Language. After explaining the objective of the study and seeking both verbal and written informed consent, the respondents who opted for self-administered questionnaire were given that chance with the condition that they seek any clarification as and when the need be. Where their partners were present, permission was obtained from their partners in addition to their consent before data collection. Data collection took place in households at convenient locations far away from the hearing distance of any third party to avoid information bias and to ensure confidentiality and privacy.

2.7. Data processing and analysis

The first step of data analysis was to check for accuracy, consistency and completeness of the data. Each completed questionnaire was checked for accuracy and consistency of the responses to the items on the instrument by BOA. After editing, a template was developed by YA and BOA and used to develop a data analysis matrix with Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 21, as well as coding responses to the items on the instrument. After coding, the data was then entered into the matrix.

After data entry, the data was screened to check for errors by the researchers. On the level of male involvement in ANC, 7 questions were measured using dichotomous responses (see Instrument_MI copy.docx).

Binary responses from these seven questions indicating that the respondent participated in a particular aspect of ANC were summed to give a composite involvement index score, with higher index scores indicating ‘high involvement’ and lower scores indicating ‘low involvement’ [32]. Any respondent who chose 0–3 ‘Yes’ for all the 7 items was put into the category of ‘low involvement’ in ANC. Respondents who chose 4–7 ‘Yes’ were put into the category ‘high involvement’ in ANC. The data were analysed using both descriptive (frequencies and percentages) and inferential statistics (binary logistic regression). The choice of this statistical technique was influenced by the fact that, the dependent variable (male involvement in ANC) was categorized into two groups ‘low involvement’ and ‘high involvement’ and the independent variables were measured on both categorical and continuous scales [33]. The results were interpreted using odds ratio (OR) and p-values at 95% confidence interval.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

Table 1 presents results on the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. The results indicate that 42.3% of the respondents were aged 20–29 years. Again, most of the respondents (55%) were married whiles 14% were either separated or divorced. With educational level, approximately 49% of the respondents had Junior High School education and 6.3% had Tertiary education (see Table 1). The study further found that 76.3% of the respondents were self-employed and most of them (94.7%) were Christians. The results in Table 1 further show that 59.3% of the respondents had 2-4 children and most of them (64.3%) were living with their partners.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

| Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 20-29 | 106 | 35.3 |

| 30-39 | 127 | 42.3 |

| 40-49 | 67 | 22.3 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 165 | 55.0 |

| Cohabiting | 93 | 31.0 |

| Separated/divorced | 42 | 14.0 |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary | 34 | 11.3 |

| Junior secondary | 148 | 49.3 |

| Senior secondary | 59 | 19.7 |

| Tertiary | 19 | 6.3 |

| No formal education | 40 | 13.3 |

| Occupation | ||

| Unemployed | 46 | 15.3 |

| Self-employed | 229 | 76.3 |

| Civil/public servant | 25 | 8.3 |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 284 | 94.7 |

| Other | 16 | 5.3 |

| Number of children | ||

| 1 child | 79 | 26.3 |

| 2–4 children | 178 | 59.3 |

| 5 or more children | 43 | 14.3 |

| Living with partner | ||

| No | 107 | 35.7 |

| Yes | 193 | 64.3 |

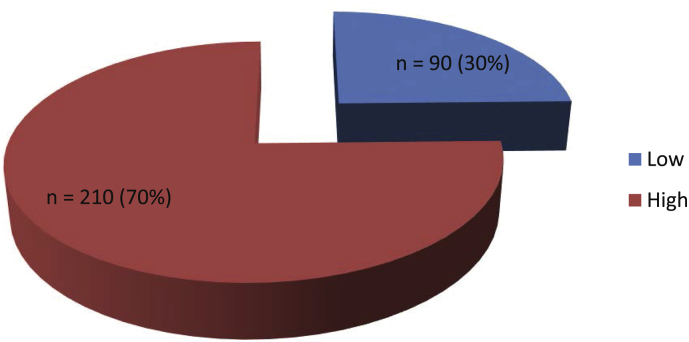

3.2. Level of male involvement in ANC

On the level of male involvement in ANC, the results of the study showed that 70% (n = 210) of the participants reported high male involvement in ANC while 30% (n = 90) reported low male involvement in ANC (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Level of male involvement in ANC.

3.3. Multivariate analysis of the barriers to male involvement in ANC

3.3.1. Socio-demographic barriers

Table 2 presents results on the perception of women on the socio-demographic barriers to ANC. With age, the results show that respondents whose partners were aged 50–59 years were less likely to report high male involvement in ANC compared to those whose partners were aged 20–29 years (OR = 0.47, 95% CI = [0.35–0.86], p = 0.03). With marital status, respondents whose partners were separated/divorced were less likely to report high male involvement in ANC compared to those whose partners were married (OR = 0.35, 95% CI = [0.14–0.89, p = 0.03). In relation to living arrangement, respondents whose partners were living together with them were about two times more likely to report high male involvement in ANC compared to those who did not live with their partners (OR = 2.17, 95% CI = [1.17–4.04], p = 0.01).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic barriers to male involvement in ANC

| Variables |

Wald |

B |

OR |

p-value |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of partner | |||||

| 20-29 | Ref | ||||

| 30-39 | 1.58 | -0.53 | 0.59 | 0.21 | 0.26–1.35 |

| 40-49 | 0.65 | -0.39 | 0.68 | 0.42 | 0.26–1.76 |

| 50-59 | 3.08 | -0.76 | 0.47 | 0.03∗∗ | 0.35–0.86 |

| Marital status of partner | |||||

| Married | Ref | ||||

| Cohabiting | 1.19 | -0.40 | 0.67 | 0.28 | 0.33–1.38 |

| Separated/Divorced | 4.85 | -1.05 | 0.35 | 0.03∗∗ | 0.14–0.89 |

| Educational level of partner | |||||

| No formal education | Ref | ||||

| Primary | 0.57 | 0.43 | 1.54 | 0.45 | 0.50–4.74 |

| JHS | 0.02 | 0.07 | 1.08 | 0.90 | 0.34–3.41 |

| SHS | 0.04 | 0.13 | 1.14 | 0.85 | 0.30–4.28 |

| Tertiary | 1.38 | -0.94 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.08–1.87 |

| Occupation of partner | |||||

| Unemployed | Ref | ||||

| Self-employed | 1.45 | -0.98 | 0.38 | 0.23 | 0.08–1.85 |

| Civil/Public servant | 0.17 | -0.36 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.13–3.79 |

| Religion of partner | |||||

| Christianity | Ref | ||||

| Other | 0.13 | -0.10 | 0.91 | 0.72 | 0.54–1.53 |

| No. of Children of partner | |||||

| 1 child | Ref | ||||

| 2–4 children | 0.06 | 0.09 | 1.09 | 0.81 | 0.53–2.26 |

| 5 or more children | 0.43 | -0.36 | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.24–2.05 |

| Living with partner | |||||

| No | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 6.00 | 0.78 | 2.17 | 0.01∗∗ | 1.17–4.04 |

∗p < 0.10, ∗∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.01.

3.3.2. Socio-cultural barriers

Table 3 presents results on the perception of females on the socio-cultural barriers to male involvement in ANC. The results show that respondents who agreed that it is unacceptable for a man to carry out household chores for his wife when she is pregnant were less likely to report high male involvement in ANC compared to those who disagreed (OR = 0.36, 95% CI = [0.15–0.90], p = 0.03). Again, respondents who agreed that husbands will be seen as being controlled by their partners if they escort their wives to ANC were less likely to report high male involvement in ANC (OR = 0.45, 95% CI = [0.23–0.88], p = 0.02).

Table 3.

Socio-cultural barriers to male involvement in ANC

| Variables |

Wald |

B |

OR |

p-value |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ridicule from friends does not allow husbands to accompany their partners for ANC | |||||

| Disagree | Ref | ||||

| Agree | 0.65 | 0.31 | 1.36 | 0.42 | 0.64–2.88 |

| It is unacceptable for a man to carry out household chores for his wife when she is pregnant | |||||

| Disagree | Ref | ||||

| Agree | 4.79 | -1.02 | 0.36 | 0.03∗∗ | 0.15–0.90 |

| In our culture, men are prohibited from escorting their wives for ANC | |||||

| Disagree | Ref | ||||

| Agree | 3.23 | 1.44 | 4.23 | 0.07 | 0.88–20.3 |

| Even if a woman is pregnant, she still has to perform her normal duties in the home | |||||

| Disagree | Ref | ||||

| Agree | 0.13 | -0.10 | 0.91 | 0.72 | 0.54–1.53 |

| Husbands will be seen as being controlled by their partners if they escort their wives to ANC | |||||

| Disagree | Ref | ||||

| Agree | 5.56 | -0.80 | 0.45 | 0.02∗∗ | 0.23–0.88 |

∗p < 0.10, ∗∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.01.

3.3.3. Health facility barriers

Table 4 presents results on the health facility factors that influence male involvement in ANC. The results show that respondents who agreed that long waiting time at the health facility is a health facility factor that influences male involvement in ANC were less likely to report high male involvement in ANC compared to those who disagreed (OR = 0.57, 95% CI = [0.38–0.85], p = 0.01). Again, respondents who agreed that male partners do not have enough time to accompany their partners for repeated ANC visits were less likely to indicate high male involvement in ANC (OR = 0.61, 95% CI = [0.38–0.98], p = 0.03). Finally, respondents who agreed that distance to health facilities is a health facility factor that influences male involvement in ANC were less likely to report high male involvement in ANC compared to those who disagreed (OR = 2.13, 95% CI = [1.19–6.36], p = 0.04).

Table 4.

Health facility barriers to male involvement in ANC

| Variables |

Wald |

B |

OR |

p-value |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost of healthcare prevents husbands from accompanying their partners for ANC | |||||

| Disagree | Ref | ||||

| Agree | 0.03 | -0.07 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.41–2.12 |

| Long waiting time at the health facility does not allow men to accompany their partners for ANC | |||||

| Disagree | Ref | ||||

| Agree | 7.50 | -0.57 | 0.57 | 0.01∗∗ | 0.38–0.85 |

| Ridicule from health workers prevents husbands from accompanying their partners for ANC | |||||

| Disagree | Ref | ||||

| Agree | 0.35 | -0.22 | 0.80 | 0.56 | 0.38–1.68 |

| Not involving husbands in anything that occurs at the health facility during ANC makes them reluctant to accompany their partners to the facility | |||||

| Disagree | Ref | ||||

| Agree | 0.19 | 0.19 | 1.21 | 0.67 | 0.52–2.82 |

| Male partners do not have enough time to accompany their partners for repeated ANC visits | |||||

| Disagree | Ref | ||||

| Agree | 4.22 | -0.49 | 0.61 | 0.03∗∗ | 0.39–0.98 |

| Lack of space to accommodate male partners in ANC clinics makes it difficult for them to attend ANC with their partners | |||||

| Disagree | Ref | ||||

| Agree | 0.81 | 0.42 | 1.52 | 0.37 | 0.61–3.75 |

| Distance to health facilities makes it difficult for male partners to attend ANC with their partner | |||||

| Disagree | Ref | ||||

| Agree | 3.99 | 0.93 | 2.13 | 0.04∗∗ | 1.19–6.36 |

∗p < 0.10, ∗∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

Since male involvement have proven to be an essential factor for achieving high maternal health service utilisation, we investigated women's perception about barriers inhibiting male involvement in ANC in Sekondi. Our study found that male involvement in ANC is high in Sekondi. In line with the results found in the current study, Bhatta [34] in a study on involvement of males in ANC in Kathmandu, Nepal found that the level of male involvement in ANC was high. Similar findings were obtained by Doe [20] and Kwambai et al. [35] who also found high male involvement in ANC. On the other hand, the finding of the current study is contrary to the findings of the studies by Awasthi et al. [36] and Craymah, Oppong and Tuoyire [16] who found that male involvement in ANC was low. Similarly, in a qualitative study, Secka, Helleve, Storeng, and Omar toure [37] also found male involvement in ANC to be low. Another contrary finding was obtained by Nantamu [13] in his study on factors associated with male involvement in maternal health care services in Jinja District, Uganda who found that male involvement in ANC was low. The possible reason for the high involvement of men in ANC in the current study could be the opportunity that exists within the Community-Based Health Planning Services to adopt a family-centered approach which would not only ensure that a wider number of men have access to information provided during ANC but that all significant others at the family level have access to such information [38]. This attempt was intended to ensure that men are involved in all aspects of maternal health including family planning, ANC and post-natal care services [21]. The high involvement in ANC may also be as a result of programmes such as couples' counselling and use of special education material targeting men as well as home visiting targeting pregnant women and their partners that has been adopted as interventions to increase community knowledge and change traditional perceptions of male involvement in Sekondi. This observation might also imply the availability of enabling environment that motivates men to participate in ANC. This could be from the woman, cultural setup or health facility driven factors.

On the socio-demographic barriers to male involvement in ANC, age of partner, marital status, religion, and living arrangement statistically influenced the level of male involvement in ANC. To a greater extent, socio-demographic traits of an individual greatly influence his/her thinking patterns, choices and preferences in life. A man's biological and social age, marital status and religion can immensely affect his decision to or not to involve himself in ANC. The findings of this study support the findings obtained by Ditekemena et al. [39], who conducted a review on barriers to male involvement in maternal and child health services in sub-Saharan Africa and found that marital status was associated with male involvement in ANC. Similarly, findings of the study confirm the findings obtained by Doe [20], where a significant association was found between the level of male involvement and age, marital status and religion. Similar findings were also obtained by Craymah, Oppong and Tuoyire [16], who identified that male involvement in antenatal care was influenced by partner's education, type of marriage, living arrangements, and number of children. On the other hand, the results of the study run parallel to the what Nantamu [13] reported. He realized that employment status was associated with increased likelihood of the man escorting the wife for ANC. The possible reason for the finding could be attributed to the fact that the views of women on whether their partners are involved in ANC or not depend on their socio-demographic characteristics, which varies.

On the socio-cultural barriers to male involvement in ANC, the finding that it is unacceptable for a man to carry out household chores for his wife when she is pregnant support the findings of Doe [20] who conducted a study on male partner involvement in maternity care in Ablekuma South District, Accra, Ghana and found that there were no taboos prohibiting male involvement though there was strong concern about how they will be perceived by relatives and other people if they are seen assisting their partners. Again, the finding of the study that male partners will be seen as being controlled by participants if they escort them to ANC confirms the findings of Ditekemena et al [39], who found negative perceptions towards men attending ANC services to be associated with low male involvement in ANC. The result also supports the findings of Nanjala and Wamalwa [40] where respondents affirmed that they will be perceived as being ruled by their wives if they were seen accompanying their wives to a health facility. Craymah, Oppong and Tuoyire [16] also found that prohibitive cultural norms and gender roles serve as barriers to male involvement in ANC. The reason for this finding could be explained by the existence of some gender norms that are found within some societies in Ghana that perceive that husbands should not be controlled by their wives. Where these socio-cultural norms exist, it could affect male involvement in ANC negatively.

Our study further revealed that long waiting time at the health facility, not involving husbands in anything that occurs at the health facility during ANC and distance to health facilities are barriers to male involvement in ANC. The reported long waiting time serving a threat to male involvement in ANC support the findings of Nantamu [13], who found that long waiting time at the health unit is a contributing factor to low male involvement in ANC. Similarly, the results further confirm the findings obtained by Secka et al. [37] who found that long waiting time of antenatal and laboratory services are healthcare environment factors associated with male involvement in ANC. The finding on non-involvement of men in ANC services provision confirm the findings of Ditekemena et al. [39] who highlighted lack of space to accommodate male partners in ANC clinics as barriers to male involvement in ANC. The finding of Doe [20] on distance to the health facility as a barrier to male involvement in ANC is also confirmed by findings of the current study. The reason for long waiting time, not involving men in activities that occur during ANC visits and distance to the health facility influencing male involvement in ANC could be due to the fact that healthcare delivery in Ghana goes through a lot of processes that require so much waiting time. As a result of this, females who go for ANC visits “waste” some time at the health facility before they are attended to. In situations where males accompany their partners and notice situation at the facility, possibly deters them from accompanying their partners for subsequent ANC visits. Finally, it is possible that the nature of services delivered during ANC visits make men feel that their presence at the facility will add nothing to the services rendered to their partners. This can make it difficult for them to be involved in ANC visits.

4.1. Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This study is unique because it arose out of obscure literature in Ghana on the perception of women on barriers to male involvement in ANC. The decision to explore all the possible barriers to male involvement in ANC (socio-demographic, socio-cultural and health facility factors) makes the study very comprehensive. Another strength is the high response rate and the relatively large sample size. One of the weaknesses of this study is the use of a cross-sectional study design that makes it impossible to provide a causal relationship. The variations in the distance to the various health centres or hospitals is also a limitation that needs to be acknowledged. Another potential weakness of this study is that we relied upon husband's behavior from the report the women gave, without including direct observations. There is the possibility of social desirability bias. However, given the variety of responses, we do not believe such social desirability biases unduly affected our data.

5. Conclusion

There is high male involvement in ANC in Sekondi. The reported high male involvement in ANC in Sekondi could bring about improvement in maternal health care. Understanding the socio-demographic, socio-cultural and health facility barriers to male involvement in ANC will help come out with strategies that will address these barriers instead of trying to deal with those that have no influence on male involvement in ANC. The findings reported call for male partner friendly policy driven environment at the various ANC visit points that would make men more comfortable to accompany their partners for ANC services. We also strongly recommend further studies to employ qualitative or mixed method approach to unravel the nuances surrounding socio-demographic, socio-cultural and health facility barriers to males involvement in ANC.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Yvonne Annoon: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Thomas Hormenu: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Bright Opoku Ahinkorah: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Abdul-Aziz Seidu, Edward Kwabena Ameyaw, Francis Sambah: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

Instrument_MI copy

References

- 1.Forbes F., Wynter K., Wade C., Zeleke B.M., Fisher J. Male partner attendance at antenatal care and adherence to antenatal care guidelines: secondary analysis of 2011 Ethiopian demographic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):145. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1775-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2016. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations . Agenda for Sustainable Development; Geneva: 2015. Transforming Our World: the 2030. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2015. WHO Recommendation on Male Involvement Interventions for Maternal and Neonatal Health. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teklesilasie W., Deressa W. Husbands’ involvement in antenatal care and its association with women’s utilization of skilled birth attendants in Sidama zone, Ethiopia: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):315. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1954-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kassebaum N.J., Bertozzi-Villa A., Coggeshall M.S., Shackelford K.A., Steiner C., Heuton K.R., Gonzalez-Medina D., Barber R., Huynh C., Dicker D., Templin T. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet. 2014 13;384(9947):980–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60696-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merdad L., Ali M.M. Timing of maternal death: levels, trends, and ecological correlates using sibling data from 34 sub-Saharan African countries. PloS One. 2018 17;13(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fotso J.C., Ezeh A., Oronje R. Provision and use of maternal health services among urban poor women in Kenya: what do we know and what can we do? J. Urban Health. 2008 May 1;85(3):428–442. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9263-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2005. The World Health Report: Make Every Mother and Child Count. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization, UNICEF . World Health Organization; 2003. Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum, and Newborn Care: a Guide for Essential Practice. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munemo P. Women’s participation in decision making in public and Political Spheres in Ghana: constrains and strategies. J. Cult. Soc. Dev. 2017;(37):47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asuako J. 2017. Women’s Political Participation—A Catalyst for Gender Equality and Women Empowerment in Ghana.http://www.gh.undp.org/content/ghana/en/home/ourperspective/ourperspectivearticle/2017/01/23/women-spolitica l-participation-a-catalyst-for-gender-equality-and-women-empowerment-in-ghana.html Retrieved on 12/01/19 from. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nantamu D.P. Makerere University; 2011. Factors Associated with Male Involvement in Maternal Health Care Services in Jinja District, Uganda. Masters dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tadesse M., Boltena A.T., Asamoah B.O. Husbands' participation in birth preparedness and complication readiness and associated factors in Wolaita Sodo town, Southern Ethiopia. Afr. J. Primary Health Care Family Med. 2018;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kululanga L.I., Sundby J., Chirwa E. Striving to promote male involvement in maternal health care in rural and urban settings in Malawi-a qualitative study. Reprod. Health. 2011 Dec;8(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craymah J.P., Oppong R.K., Tuoyire D.A. Male involvement in maternal health care at Anomabo, central region, Ghana. Inte. J. Reprod. Med. 2017:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2017/2929013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tokhi M., Comrie-Thomson L., Davis J., Portela A., Chersich M., Luchters S. Involving men to improve maternal and newborn health: a systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions. PloS One. 2018 Jan 25;13(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou X., Ma N. Empowering women: the effect of women's decision-making power on reproductive health services uptake: evidence from Pakistan. Policy Res. Working Papers. 2011 doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yende N., Van Rie A., West N.S., Bassett J., Schwartz S.R. Acceptability and preferences among men and women for male involvement in antenatal care. J. Pregnancy. 2017:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2017/4758017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doe R.D. University of Ghana; 2013. Male Partner Involvement in Maternity Care in Ablekuma South District, Accra, Ghana.http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh/bitstream/handle/123456789/5898/Roseline%20Dansowaa%20Doe_Male%20Partner%20Involvement%20in%20Maternity%20Care%20in%20Ablekuma%20South%20District,%20Accra,%20Ghana_2013.pdf?sequence=1 Doctoral dissertation. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell G.T. University of Ghana; 2012. Male Involvement in Maternal Health Decision-Making in Nkwanta South District, Ghana.http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh/bitstream/handle/123456789/5587/Georgia%20Tammy%20Mitchell_Male%20Involvement%20in%20Maternal%20Health%20Decision-Making%20in%20Nkwanta%20South%20District%2C%20Ghana_2012.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y Doctoral dissertation. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sham-Una U. 2016. Factors Influencing Male Participation in Antenatal Care in the Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana.http://ir.knust.edu.gh/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/8781/corrected%20thesis%20210515.pdf?sequence=1 Doctoral dissertation. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghana Statistical Service . Accra: Ghana Statistical Service. 2010. 2010. Population and housing census. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarantakos S. Palgrave Macmillan; New York: 2005. Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orish V.N., Onyeabor O.S., Boampong J.N., Afoakwah R., Nwaefuna E., Acquah S., Sanyaolu A.O., Iriemenam N.C. Prevalence of intermittent preventive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) use during pregnancy and other associated factors in Sekondi-Takoradi, Ghana. Afr. Health Sci. 2015;15(4):1087–1096. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v15i4.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akinyoade A. Institute of Social Studies, The Hague: Shaker Publishing BV; 2008. Dynamics of Reproductive Behavoiur in Rural Coastal Communities of Southern Ghana. PhD. Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teye J.K. Economic value of children and fertility preferences in a fishing community in Ghana. Geo J. 2013;78(4):697–708. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghana Statistical Service; Ghana Health Service and ICF Macro. Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2014: Key Indicators. Accra: GSS, GHS and ICF Macro; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghana Statistical Service, Ghana Health Service and ICF Macro . Key Indicators. Accra: GSS, GHS and ICF Macro. 2015. 2015. Ghana demographic and health survey 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krejcie R.V., Morgan D.W. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970;30(3):607–610. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogah J.K. Adwinsa Publications (Gh) Ltd; Legon, Accra: 2013. Decision Making in the Research Process: Companion to Students and Beginning Researchers. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ampt F., Mon M.M., Than K.K., Khin M.M., Agius P.A., Morgan C., Davis J., Luchters S. Correlates of male involvement in maternal and newborn health: a cross-sectional study of men in a peri-urban region of Myanmar. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0561-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pallant J. McGraw-Hill Education; London, UK: 2013. SPSS Survival Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhatta D.N. Involvement of males in antenatal care, birth preparedness, exclusive breast feeding and immunizations for children in Kathmandu, Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwambai T.K., Dellicour S., Desai M., Ameh C.A., Person B., Achieng F., Mason L., Laserson K.F., Ter Kuile F.O. Perspectives of men on antenatal and delivery care service utilisation in rural western Kenya: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Awasthi A., Nandan D., Mehrotra A.K., Shankar R. Male participation in maternal care in urban slums of district Agra. Indian J. Prev. Soc. Med. 2008;39:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Secka E., Helleve A., Storeng K., Omar toure’ S. University of Oslo; 2010. Men’s Involvement in Care and Support during Pregnancy and Childbirth: A Qualitative Study Conducted in Gambia. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nyonator F.K., Awoonor-Williams J.K., Phillips J.F., Jones T.C., Miller R.A. The Ghana community-based health planning and services initiative for scaling up service delivery innovation. Health Pol. Plann. 2005;20(1):25–34. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czi003. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ditekemena J., Koole O., Engmann C., Matendo R., Tshefu A., Ryder R., Colebunders R. Determinants of male involvement in maternal and child health services in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. Reprod. Health. 2012;9(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nanjala M., Wamalwa D. Determinants of male partner involvement in promoting deliveries by skilled attendants in Busia, Kenya. Global J. Health Sci. 2012;4(2):60. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v4n2p60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Instrument_MI copy