Abstract

The risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) to maternal and newborn health has yet to be determined. Several reports suggest pregnancy does not typically increase the severity of maternal disease; however, cases of preeclampsia and preterm birth have been infrequently reported. Reports of placental infection and vertical transmission are rare. Interestingly, despite lack of SARS-CoV-2 placenta infection, there are several reports of significant abnormalities in placenta morphology. Continued research on pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2 and their offspring is vitally important.

Keywords: COVID-19, placenta, pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the etiologic agent of coronavirus disease (COVID-19), was first reported in Wuhan, China in December of 2019 and is now a global pandemic. To date, the World Health Organization reports over 4 million cases and 300,000 deaths. There has been a rapid increase in knowledge of the genetic, virologic, epidemiologic, and clinical aspects of COVID-19; however, there are far fewer reports describing the risks and specific effects of SARS-CoV-2 in pregnant women and their newborns. In this paper, we have included both peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed preprints to capture the most up-to-date information.

REVIEW

Pregnancy increases the risk of adverse obstetrical and neonatal outcomes from many respiratory viral infections. The maternal immune system is altered in pregnancy to prevent rejection of the fetus and assist in fetal development (25). Some viral infections cause a more severe or prolonged disease in pregnant women (34). SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) resulted in high rates of miscarriage, maternal death, and preterm birth (44).Multiple studies of influenza have demonstrated an increased risk of maternal morbidity and mortality when compared with nonpregnant women. In contrast, the majority of outcomes in pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2 (5, 8, 9, 11, 12, 22, 27, 38, 43, 46, 48, 50, 51, 53) are no different than in the general population. The most common symptom of COVID-19 in these women is fever, but many also experience cough, shortness of breath, and diarrhea. Occasionally severe infections required mechanical ventilation (2, 13, 14, 24, 27, 30, 46) but rarely led to death (13).

However, although most COVID infections in pregnant women are mild, data are emerging that demonstrate significant placental pathology in SARS-CoV-2 pregnancies despite the lack of detectable or very low levels of mRNA or protein SARS-CoV-2 (4, 12, 17, 26, 27, 35, 36, 41, 43). Although there are case reports showing SARS-CoV-2 virions in syncytiotrophoblasts in placental villi by electron microscopy (1, 17, 28) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (5, 28, 36), an important question that remains unanswered is whether SARS-CoV-2 replicates in the placenta and is a cause of the described placenta abnormalities or whether SARS-CoV-2 is an “innocent bystander”. It is also important to note that the placenta abnormalities that have been described occur mostly in women who are asymptomatic or have mild-to-moderate disease, suggesting that these defects are not simply due to severe COVID disease.

The placenta abnormalities that have been described in SARS-CoV-2-infected pregnant women include diffuse perivillous fibrin, fetal vascular malperfusion evidenced by thrombi in the fetal vessels, choriohemangioma, maternal vascular malperfusion, and multifocal infarctions (17, 26, 36). In some of these cases, SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the placenta (5, 17, 28, 36). Lack of controls and issues with nonspecific staining (16) in some of these studies complicate interpretation of these results. Importantly, in the vast majority of cases, placentas were negative for SARS-CoV-2 as measured by PCR (12, 22, 26, 27, 36, 41, 43). Therefore, the abnormalities noted on placenta pathology suggest the placenta is susceptible to the effects of maternal COVID-19 disease largely in the absence of infection. It is important to note that in many cases these abnormalities could be due to maternal comorbidities such as hypertension, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes. Thus, there is a critical need for careful systematic studies to determine the prevalence of infection and replication of SARS-CoV-2 in the placenta and its association with placenta abnormalities.

It also remains to be determined whether SARS-CoV-2 can be transmitted from a pregnant woman to her fetus, a process termed vertical transmission. Importantly, transmission is expected to have different effects across the three trimesters of pregnancy. Transplacental passage of virus usually increases with advancing gestational age, whereas the severity of fetal injuries decreases from embryopathy and embryo/fetal death in the first trimester to fetal infection and immune response driven disease in the second and third trimesters. Unlike many other viral diseases, viremia in SARS-CoV-2 is found in only 1% of symptomatic patients and is generally low and transient (19).

Most case series report the birth of normal term newborns to SARS-CoV-2-positive mothers with mild or moderate disease (8, 22, 27, 46, 48, 51–53). In contrast, preterm births occur fairly often in women with severe disease mostly as a result of early delivery for maternal indications, although there are sporadic reports of spontaneous preterm births (9, 12, 13, 22, 27, 28, 30, 31, 43, 45, 46, 50, 53). Spontaneous abortion has also been reported twice in early pregnancy (5, 45), and fetal demise has been reported 5 times (13, 24). There have been case reports describing newborns with symptoms that required admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for increased work of breathing, tachycardia, fever, gastrointestinal symptoms, and signs of pulmonary infection on computed tomography (2, 7, 12, 27, 41, 48, 52, 53); 2 of 5 had nasopharyngeal swabs that were positive for SARS-CoV-2. Interestingly, some symptomatic babies tested negative for SARS-CoV-2. In one case, a SARS-CoV-2-positive infant born at 31 wk required resuscitation and was diagnosed with pneumonia, but the authors report they suspected sepsis with Enterobacter (52). Thus, with the exception of these rare cases, neonates have been born healthy to SARS-CoV-2-positive mothers. However, it is yet to be determined if infection at an earlier gestation will have a different effect on neonatal health and long-term outcomes.

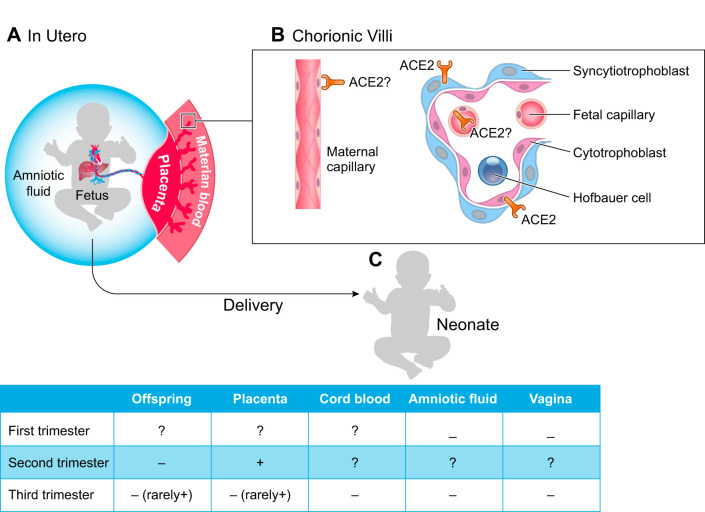

Neonates can be affected by maternal viral infection either directly by the virus (vertical transmission) or indirectly by the maternal response to the virus (Fig. 1). Considerable evidence demonstrates the lack of vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Multiple newborns have been tested for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 at delivery, and viral RNA has not been detected in cord blood, throat and nasopharyngeal swabs, urine, and feces (5, 7, 11, 12, 22, 27, 30, 41, 43, 45, 46, 50, 51). Amniotic fluid samples have also been collected from COVID-positive pregnancies and have mostly tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 (5, 8, 12, 27, 43, 45, 46, 49). Neonatal testing, 24 h or more after delivery, has infrequently been reported positive for virus (27, 30, 31, 41, 48, 52); however, due to the delay in testing, it is possible these infants were infected after delivery. There is one case report of SARS-CoV-2 in two neonates at birth, but these infants were asymptomatic with the exception of mild initial feeding difficulties (28). Additionally, despite careful isolation, an infant born at 33 wk tested positive 16 h and again 48 h postdelivery (2). The authors suggest this infant was infected either during caesarean delivery or in utero. This infant required admission to the NICU for low Apgar scores and ventilator support. Most infants in these studies were delivered by caesarean section, and it is possible that newborns could be infected during vaginal delivery. However, vaginal swabs tested negative in a 37-wk caesarean section delivery (12) and were negative for SARS-CoV-2 in 6 women at hospital admission (45). Interestingly, despite lack of virus detected in the neonate at delivery, antibodies have been detected in neonatal blood (51). In particular, IgM was reported to be elevated, suggesting fetal exposure to virus in utero (51). It is important to note that IgM antibody testing results in a high probability of false positives (19), but these results suggest continued testing for neonatal antibodies may be informative.

Fig. 1.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in pregnancy and the newborn. A: graphical representation of the maternal fetal interface. B: placenta villus and maternal capillary showing localization of the receptor [angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)] for SARS-CoV-2. C: SARS-CoV-2 infectivity.

DISCUSSION

Overall, there is little evidence of vertical transmission in most cases of COVID-19-positive pregnancies. The fact that viremia is found in 1% of symptomatic patients and is generally low and transient may play a role (42). However, other mechanisms are likely to be just as important or more so in the protection of the fetus against vertical transmission. The maternal fetal interface barriers protect the fetus against infection. For example, the syncytiotrophoblasts coordinate an immune response to infection and also serve as a physical barrier to viral passage (29, 47). Immune cells in the placenta also have antiviral capacity (47). Finally, previous studies have shown that trophoblast-derived extracellular vesicles harboring a unique group of microRNAs (miRNAs), expressed from the chromosome 19 miRNA cluster, confer viral resistance to recipient cells, suggesting a paracrine function that allows communication between placental cells to regulate their immunity to viral infections (10).

The ability of a virus to replicate and infect the placenta is also virus dependent. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, cell entry requires binding of the spike protein to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (15). The virus is then primed by cellular proteases like transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) (15) and possibly cathepsin B/L7 (37) and furin (6). Using previously published single-cell RNAseq data, authors have detected robust expression of ACE2 in the placenta (21, 37) but not TMPRSS2 (37). Very recently, two reports using single-nucleotide RNAseq or single-cell RNAseq were performed during gestation and found expression of ACE2 but either no or very low levels of TMPRSS2 in the placenta (3, 32). There has not been a systematic evaluation for the presence and function of other proteases contributing to viral entry and replication in the cell in the placenta. ACE2 has been detected by immunohistochemistry in syncytiotrophoblasts, cytotrophoblasts, endothelium, and vascular smooth muscle (40). Interestingly, ACE2 is involved in placentation, including trophoblast migration, vascular remodeling, and maternal vasodilation (33, 39). ACE2 has also been implicated in pregnancy complications such as miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, and preeclampsia (40). Therefore, if SARS-CoV-2 changes the expression of ACE2 in the placenta, as SARS-CoV-1 has been shown to do in the lung (20), there is the potential for placental abnormalities and pregnancy complications. The presence of ACE2 in the placenta suggests there is potential to bind SARS-CoV-2, initiating viral infection; however, the mechanisms underlying the inability of SARS-CoV-2 to infect and replicate in placenta are unknown.

At this time, vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is considered unlikely; however, it appears that there is considerable potential for SARS-CoV-2 to affect placental function and fetal development, and research in this area is lacking. Continued research particularly focusing on detecting SARS-CoV-2 at early gestational time points is also required. Finally, careful systemic studies with appropriate controls are necessary before making any conclusions on maternal or neonatal effects of COVID-19.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.N.G. and R.A.S. drafted manuscript; T.N.G. and R.A.S. edited and revised manuscript; T.N.G. and R.A.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Algarroba GN, Rekawek P, Vahanian SA, Khullar P, Palaia T, Peltier MR, Chavez MR, Vintzileos AM. Visualization of SARS-CoV-2 virus invading the human placenta using electron microscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. In press. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzamora MC, Paredes T, Caceres D, Webb CM, Valdez LM, La Rosa M. Severe COVID-19 during pregnancy and possible vertical transmission. Am J Perinatol 37: 861–865, 2020. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashray NB, Chakarborty P, Colaco S, Mishra A, Chhabria K, Jolly M, Modi D. Single-cell RNA-seq identifies cell subsets in human placenta that highly expresses factors to drive pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 (Preprint). bioRxiv 2020. doi: 10.20944/preprints202005.0195.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Baergen RN, Heller DS. Placental pathology in Covid-19 positive mothers: preliminary findings. Pediatr Dev Pathol 23: 177–180, 2020. doi: 10.1177/1093526620925569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baud D, Greub G, Favre G, Gengler C, Jaton K, Dubruc E, Pomar L. Second-trimester miscarriage in a pregnant woman with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA 323: 2198, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bestle D, Heindl MR, Limburg H, Van Lam van T, Pilgram O, Moulton H, Stein DA, Hardes K, Eickmann M, Dolnik O, Rohde C, Becker S, Klenk HD, Garten W, Steinmetzer T, Böttcher-Friedbertshäuser E. TMPRSS2 and furin are both essential for proteolytic activation and spread of SARS-CoV-2 in human airway epithelial cells and provide promising drug targets (Preprint). bioRxiv 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.15.042085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Breslin N, Baptiste C, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Miller R, Martinez R, Bernstein K, Ring L, Landau R, Purisch S, Friedman AM, Fuchs K, Sutton D, Andrikopoulou M, Rupley D, Sheen JJ, Aubey J, Zork N, Moroz L, Mourad M, Wapner R, Simpson LL, D’Alton ME, Goffman D. Coronavirus disease 2019 infection among asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women: two weeks of confirmed presentations to an affiliated pair of New York City hospitals. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2: 100118, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H, Guo J, Wang C, Luo F, Yu X, Zhang W, Li J, Zhao D, Xu D, Gong Q, Liao J, Yang H, Hou W, Zhang Y. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet 395: 809–815, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Li Q, Zheng D, Jiang H, Wei Y, Zou L, Feng L, Xiong G, Sun G, Wang H, Zhao Y, Qiao J. Clinical characteristics of pregnant women with Covid-19 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med 382: e100, 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delorme-Axford E, Donker RB, Mouillet JF, Chu T, Bayer A, Ouyang Y, Wang T, Stolz DB, Sarkar SN, Morelli AE, Sadovsky Y, Coyne CB. Human placental trophoblasts confer viral resistance to recipient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 12048–12053, 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304718110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong L, Tian J, He S, Zhu C, Wang J, Liu C, Yang J. Possible vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from an infected mother to her newborn. JAMA 323: 1846–1848, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan C, Lei D, Fang C, Li C, Wang M, Liu Y, Bao Y, Sun Y, Huang J, Guo Y, Yu Y, Wang S. Perinatal transmission of COVID-19 associated SARS-CoV-2: should we worry? Clin Infect Dis. In press. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hantoushzadeh S, Shamshirsaz AA, Aleyasin A, Seferovic MD, Aski SK, Arian SE, Pooransari P, Ghotbizadeh F, Aalipour S, Soleimani Z, Naemi M, Molaei B, Ahangari R, Salehi M, Oskoei AD, Pirozan P, Darkhaneh RF, Laki MG, Farani AK, Atrak S, Miri MM, Kouchek M, Shojaei S, Hadavand F, Keikha F, Hosseini MS, Borna S, Ariana S, Shariat M, Fatemi A, Nouri B, Nekooghadam SM, Aagaard K. Maternal death due to COVID-19. Am J Obstet Gynecol 223: 109.e1–109.e16, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirshberg A, Kern-Goldberger AR, Levine LD, Pierce-Williams R, Short WR, Parry S, Berghella V, Triebwasser JE, Srinivas SK. Care of critically ill pregnant patients with COVID-19: a case series. Am J Obstet Gynecol. In press. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, Müller MA, Drosten C, Pöhlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181: 271–280.e8, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honig A, Rieger L, Kapp M, Dietl J, Kämmerer U. Immunohistochemistry in human placental tissue–pitfalls of antigen detection. J Histochem Cytochem 53: 1413–1420, 2005. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6664.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosier H, Farhadian SF, Morotti RA, Deshmukh U, Lu-Culligan A, Campbell KH, Yasumoto Y, Vogels CB, Casanovas-Massana A, Vijayakumar P, Geng B, Odio CD, Fournier J, Brito AF, Fauver JR, Liu F, Alpert T, Tal R, Szigeti-Buck K, Perincheri S, Larsen CP, Gariepy AM, Aguilar G, Fardelmann KL, Harigopal M, Taylor HS, Pettker CM, Wyllie AL, Dela Cruz CS, Ring AM, Grubaugh ND, Ko AI, Horvath TL, Iwasaki A, Reddy UM, Lipkind HS. SARS-CoV-2 infection of the placenta. J Clin Invest. In press. doi: 10.1172/JCI139569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Kimberlin DW, Stagno S. Can SARS-CoV-2 infection be acquired in utero?: more definitive evidence is needed. JAMA. In press. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao S, Gao H, Guo F, Guan B, Huan Y, Yang P, Zhang Y, Deng W, Bao L, Zhang B, Liu G, Wang Z, Chappell M, Liu Y, Zheng D, Leibbrandt A, Wada T, Slutsky AS, Liu D, Qin C, Jiang C, Penninger JM. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med 11: 875–879, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li M, Chen L, Zhang J, Xiong C, Li X. The SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 expression of maternal-fetal interface and fetal organs by single-cell transcriptome study. PLoS One 15: e0230295, 2020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Zhao R, Zheng S, Chen X, Wang J, Sheng X, Zhou J, Cai H, Fang Q, Yu F, Fan J, Xu K, Chen Y, Sheng J. Lack of vertical transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, China. Emerg Infect Dis 26: 1335–1336, 2020. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lokken EM, Walker CL, Delaney S, Kachikis A, Kretzer NM, Erickson A, Resnick R, Vanderhoeven J, Hwang JK, Barnhart N, Rah J, Mccartney SA, Ma KK, Huebner EM, Thomas C, Sheng JS, Paek BW, Retzlaff K, Kline CR, Munson J, Blain M, Lacourse SM, Deutsch G, Adams Waldorf K. Clinical characteristics of 46 pregnant women with a SARS-CoV-2 infection in Washington State. Am J Obstet Gynecol. In press. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mor G, Aldo P, Alvero AB. The unique immunological and microbial aspects of pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol 17: 469–482, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulvey JJ, Magro CM, Ma LX, Nuovo GJ, Baergen RN. Analysis of complement deposition and viral RNA in placentas of COVID-19 patients. Ann Diagn Pathol 46: 151530, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2020.151530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nie R,Wang SS, Yang Q, Fan C, Liu Y, He W, Jiang M, Liu C, Zeng W, Wu J, Oktay K, Feng L, Jin L. Clinical features and the maternal and neonatal outcomes of pregnant women with coronavirus disease 2019 (Preprint). medRxiv 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.22.20041061. [DOI]

- 28.Patanè L, Morotti D, Giunta MR, Sigismondi C, Piccoli MG, Frigerio L, Mangili G, Arosio M, Cornolti G. Vertical transmission of COVID-19: SARS-CoV-2 RNA on the fetal side of the placenta in pregnancies with COVID-19 positive mothers and neonates at birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM In press. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pereira L. Congenital viral infection: traversing the uterine-placental interface. Annu Rev Virol 5: 273–299, 2018. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-092917-043236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierce-Williams RA, Burd J, Felder L, Khoury R, Bernstein PS, Avila K, Penfield CA, Roman AS, DeBolt CA, Stone JL, Bianco A, Kern-Goldberger AR, Hirshberg A, Srinivas SK, Jayakumaran JS, Brandt JS, Anastasio H, Birsner M, O’Brien DS, Sedev HM, Dolin CD, Schnettler WT, Suhag A, Ahluwalia S, Navathe RS, Khalifeh A, Anderson K, Berghella V. Clinical course of severe and critical COVID-19 in hospitalized pregnancies: a US cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. In press. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piersigilli F, Carkeek K, Hocq C, van Grambezen B, Hubinont C, Chatzis O, Van der Linden D, Danhaive O. COVID-19 in a 26-week preterm neonate. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 4: 476–478, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30140-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pique-Regi R, Romero R, Tarca AL, Luca F, Xu Y, Alazizi A, Leng Y, Hsu CD, Gomez-Lopez N. Does the human placenta express the canonical cell entry mediators for SARS-CoV-2? (Preprint). bioRxiv 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.18.101485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Pringle KG, Tadros MA, Callister RJ, Lumbers ER. The expression and localization of the human placental prorenin/renin-angiotensin system throughout pregnancy: roles in trophoblast invasion and angiogenesis? Placenta 32: 956–962, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Racicot K, Mor G. Risks associated with viral infections during pregnancy. J Clin Invest 127: 1591–1599, 2017. doi: 10.1172/JCI87490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz DA. An analysis of 38 pregnant women with COVID-19, their newborn infants, and maternal-fetal transmission of SARS-CoV-2: maternal coronavirus infections and pregnancy outcomes. Arch Pathol Lab Med 144: 799–805, 2020. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2020-0901-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shanes ED, Mithal LB, Otero S, Azad HA, Miller ES, Goldstein JA. Placental pathology in COVID-19. Am J Clin Pathol 154: 23–32, 2020. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sungnak W, Huang N, Bécavin C, Berg M, Queen R, Litvinukova M, Talavera-López C, Maatz H, Reichart D, Sampaziotis F, Worlock KB, Yoshida M, Barnes JL; HCA Lung Biological Network . SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat Med 26: 681–687, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0868-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutton D, Fuchs K, D’Alton M, Goffman D. Universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 in women admitted for delivery. N Engl J Med 382: 2163–2164, 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valdés G, Corthorn J, Bharadwaj MS, Joyner J, Schneider D, Brosnihan KB. Utero-placental expression of angiotensin-(1-7) and ACE2 in the pregnant guinea-pig. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 11: 5, 2013. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valdés G, Neves LA, Anton L, Corthorn J, Chacón C, Germain AM, Merrill DC, Ferrario CM, Sarao R, Penninger J, Brosnihan KB. Distribution of angiotensin-(1-7) and ACE2 in human placentas of normal and pathological pregnancies. Placenta 27: 200–207, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang S, Guo L, Chen L, Liu W, Cao Y, Zhang J, Feng L. A case report of neonatal COVID-19 infection in China. Clin Infect Dis. In press. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, Lu R, Han K, Wu G, Tan W. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA 323: 1843–1844, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X, Zhou Z, Zhang J, Zhu F, Tang Y, Shen X. A case of 2019 novel coronavirus in a pregnant woman with preterm delivery. Clin Infect Dis. In press. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong SF, Chow KM, Leung TN, Ng WF, Ng TK, Shek CC, Ng PC, Lam PW, Ho LC, To WW, Lai ST, Yan WW, Tan PY. Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 191: 292–297, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yan J, Guo J, Fan C, Juan J, Yu X, Li J, Feng L, Li C, Chen H, Qiao Y, Lei D, Wang C, Xiong G, Xiao F, He W, Pang Q, Hu X, Wang S, Chen D, Zhang Y, Poon LC, Yang H. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in pregnant women: a report based on 116 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol 223: 111.e1–111.e14, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yin M, Zhang L, Deng G, Han C, Shen M, Sun H, Zeng F, Zhang W, Chen L, Luo Q, Yao D, Wu M, Yu S, Chen H, Baud D, Chen X. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection during pregnancy in China: a retrospective cohort study (Preprint). medRxiv 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.07.20053744. [DOI]

- 47.Yockey LJ, Lucas C, Iwasaki A. Contributions of maternal and fetal antiviral immunity in congenital disease. Science 368: 608–612, 2020. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu N, Li W, Kang Q, Xiong Z, Wang S, Lin X, Liu Y, Xiao J, Liu H, Deng D, Chen S, Zeng W, Feng L, Wu J. Clinical features and obstetric and neonatal outcomes of pregnant patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective, single-centre, descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 20: 559–564, 2020. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30176-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu N, Li W, Kang Q, Zeng W, Feng L, Wu J. No SARS-CoV-2 detected in amniotic fluid in mid-pregnancy. Lancet Infect Dis. In press. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30320-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zambrano LI, Fuentes-Barahona IC, Bejarano-Torres DA, Bustillo C, Gonzales G, Vallecillo-Chinchilla G, Sanchez-Martínez FE, Valle-Reconco JA, Sierra M, Bonilla-Aldana DK, Cardona-Ospina JA, Rodríguez-Morales AJ. A pregnant woman with COVID-19 in Central America. Travel Med Infect Dis. In press. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeng H, Xu C, Fan J, Tang Y, Deng Q, Zhang W, Long X. Antibodies in infants born to mothers with COVID-19 pneumonia. JAMA 323: 1848–1849, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeng L, Xia S, Yuan W, Yan K, Xiao F, Shao J, Zhou W. Neonatal early-onset infection with SARS-CoV-2 in 33 neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Pediatr. In press. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu H, Wang L, Fang C, Peng S, Zhang L, Chang G, Xia S, Zhou W. Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Transl Pediatr 9: 51–60, 2020. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]