Severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2) and the resulting acute respiratory distress syndrome (coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19]) is responsible for a worldwide pandemic, with more than 10 million cases reported as of June 28, 2020.S1 Although severe disease requiring hospitalization is characterized by pneumonia and respiratory failure, a significant proportion also develop acute kidney injury. Within critical care admissions with COVID-19, 16% to 35% are reported as requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT).1–3,S2,S3 There is increasing recognition of an associated coagulopathy in hospitalized patients characterized by a prothrombotic state and increased venous thromboembolism. This brief review presents the current understanding of the coagulopathy associated with COVID-19, the risk of venous thrombosis, and the impact of this on management of RRT in critically ill patients with COVID-19.

Hypercoagulability Associated With COVID-19 Infection

The complex relationship between coagulation and inflammation is well described and termed “thromboinflammation.”S4 COVID-19 pneumonia is associated with pronounced changes in coagulation, with degree of coagulopathy correlating with disease severity.S5,S6 There are multiple reports of markedly elevated D-dimer, fibrinogen, Factor VIII, and von Willebrand factor in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.2,S6,S7,S8 Progressive increase in D-dimer and fibrinogen over time are associated with intensive care unit (ICU) admission and mortality.S5,S6 Changes in coagulation markers associated with COVID-19 are presented in Table 1.2,S2,S3,S5–S9 Early reports of disseminated intravascular coagulation have not been confirmed in subsequent case series.S5 Although these findings are presented as novel, one center compared laboratory parameters with a historic cohort with non–COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome and found D-dimer was lower, fibrinogen higher, and antithrombin preserved in those with COVID-19.2 Viscoelastic testing further confirms hypercoagulability in small cohorts of patients with COVID-19 admitted to ICUs.S8–S10 Additional markers of endothelial activation (soluble P-selectin and soluble thrombomodulin) also have been reported as increased in those with critical illness compared with those receiving ward-based care.S11 The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms remain unknown. Some suggest it is simply a consequence of acute respiratory distress syndrome, coined “pulmonary-induced coagulopathy” and others an “endotheliopathy” as a direct consequence of virus cell entry rather than a more systemic response to cytokine storm.4,S5,S12 Virus entry follows adhesion to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor on endothelial cells, and subsequent viral replication leads to inflammatory cell infiltrate, apoptosis, and microvascular hypercoagulability, with recent autopsy reports confirming viral inclusions within endothelial cells.S13

Table 1.

Coagulation markers in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

| Coagulation marker | Values in COVID-19 |

|---|---|

| Platelet countS2,S3,S6,S8 | Normal–mildly ↓ |

| Prothrombin timeS6,S8 | Normal–mildly ↑ |

| Fibrinogen2,S5–S9 | Normal–markedly ↑ |

| D-dimer2,S2,S3,S5–S9 | Normal–markedly ↑ |

| Factor V2 | Mildly ↑ |

| Factor VIII2,S5,S7,S8 | Normal–markedly ↑ |

| Von Willebrand antigen2,S7,S8 | Normal–markedly ↑ |

| Von Willebrand activity2,S7,S8 | Normal–markedly ↑ |

| ADAMTS-13S7 | Normal–mildly ↓ |

| Soluble P-selectinS11 | Normal–↑ |

| Soluble thrombomodulinS11 | Normal–↑ |

| AntithrombinS8,S9 | Normal–mildly ↓ |

| Protein CS8 | Normal–mildly ↑ |

| Protein S antigenS8 | Normal–↓ |

↑, increased; ↓, decreased.

Incidence of Thrombosis in COVID-19

There are an increasing number of case series reporting increased rates of venous thromboembolic events (VTE), particularly in those with critical illness and in centers using screening for VTE. The first report from China was of 81 patients admitted to ICU with 4% mortality rate and 85% discharged at the time of reporting.S14 Deep vein thrombosis was reported in 25%. No thromboprophylaxis was used, and the criteria for imaging were not reported. Subsequent case series in Europe and the United States, where thromboprophylaxis is routinely used, have reported an increased incidence in patients admitted to ICU of 5% to 69%.2,5,S15–S21 Of note, the series with the lowest incidence (5% of 79 patients) excluded segmental/subsegmental pulmonary embolism (designated “immunothrombosis”) and line-associated deep vein thrombosis from their primary endpoint.S15 In contrast, the series with the highest incidence involved a small number of patients (n = 25) and performed deep vein thrombosis imaging in all patients on admission and at 1 week post admission to ICU.S21 Of studies reporting all VTE following imaging based on clinical suspicion, VTE (predominantly pulmonary embolism) was confirmed in 16.7% to 35.0%, with cumulative incidence of up to 49.0% at 14 days.2,S17,S22 The data for symptomatic VTE are summarized in Table 2.2,5,S14,S15,S17–S20,S22 Of note, 3 series also reported bleeding rates, with major bleeding complicating 2.7% to 11.0% of ICU admissions.2,5,S15

Table 2.

Rates of venous thromboembolism in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019

| Author, country | N | Criteria for imaging | Proportion imaged | Proportion of total n with VTE | Cumulative incidence (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Samkari et al., United States5 | 144 | Clinical suspiciona | Not reported | 7.6% | 4.8%/100 patient-weeks |

| Cui et al., ChinaS14 | 81 | Not reported | Not reported | 25% DVT | Not reported |

| Desborough et al., EnglandS15 | 66 | Clinical suspicion | 29% CTPA 10% DVT scan |

15% VTE 5% “true” VTEb |

Not reported |

| Helms et al., France2 | 150 | Clinical suspicion or increase in D-dimer | 66% | 16.6% PE | Not reported |

| Klok et al., NetherlandsS16,S22 | 184 | Clinical suspicion | Not reported | 7 dS16: 15.2% VTE 14 dS22: 35.3% PE |

7 d: 27% (17–37) 14 d: 49% (41–57) |

| Lodigiani et al., ItalyS17 | 61 | Clinical suspicion | ∼20% | 8.3% VTE | 27.6% |

| Middeldorp et al., NetherlandsS18 | 75 | Clinical suspicionc | Not reported | 28% VTE | 7 d: 15% (8–24) 14 d: 28% (18–39) 21 d: 24% (21–46) |

| Poissy et al., FranceS20 | 107 | Clinical suspicion | 31.8% | 22.4% VTE | PE 15 d: 20.4% (13.1–28.7) |

| Thomas et al., EnglandS19 | 62 | Clinical suspicion | 17.7% | 9.6% VTE | 27% (10–47) |

CI, confidence interval; CTPA, computed tomography pulmonary angiogram; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Patients treated for VTE without diagnostic imaging not presented here.

“True” VTE excludes segmental/subsegmental PE and line-associated DVT.

Thirty-eight patients had DVT screening, patients with asymptomatic VTE are excluded from the table.

RRT was not been consistently reported in the preceding series, with 4 studies reporting use in 8.3% to 37.0% of the whole cohort, and one study reporting RRT use in 5 of 10 patients with VTE (VTE in 28% of patients on RRT).2,5,S15,S16,S19 Although RRT can be associated with an increased bleeding rate, the high prevalence of VTE supports the use of routine thromboprophylaxis in this patient cohort in the absence of active bleeding or severe thrombocytopenia.

Acute Kidney Injury and RRT

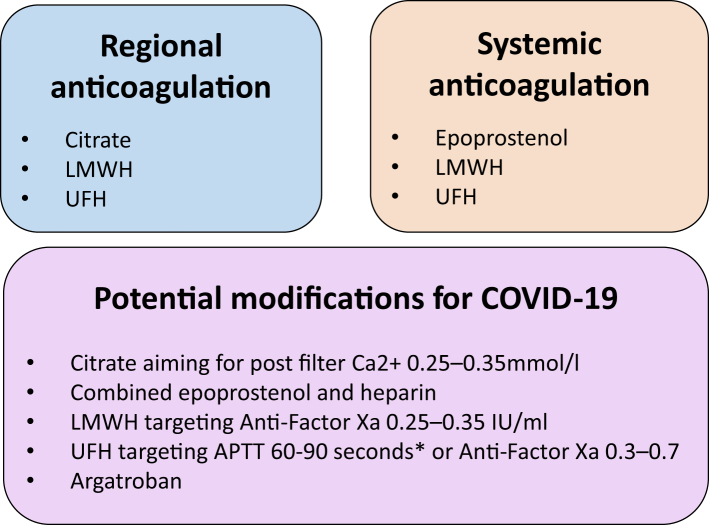

Acute kidney injury is common in critical illness, developing in up to half of patients, with 10% to 20% requiring RRT.S23 Continuous RRT is generally preferred in this setting due to the lesser impact on haemodynamic stability and opportunity for strict volume control. Blood exposure to the artificial circuit results in activation of coagulation and can lead to thrombosis with subsequent increased blood loss, nursing work load, and cost, in addition to adverse impacts on control of uremia, acidemia, and fluid balance.S24 Options to minimize circuit thrombosis include regional anticoagulation with citrate or heparin (unfractionated heparin [UFH] or low molecular weight heparin) or systemic anticoagulation (UFH, low molecular weight heparin, or prostacyclin). Citrate chelates calcium, a key cofactor for coagulation, thereby inhibiting its activation. Heparin anticoagulation is associated with an increased risk of major bleeding, reported as 10% to 50% in small case series.S25 Recent randomized controlled trials have demonstrated regional citrate is as effective in maintaining filter patency with reduced bleeding risk compared with systemic heparinization.S26,S27

COVID-19, Acute Kidney Injury, and RRT

Acute kidney injury is common in patients hospitalized with COVID, with rates of 5.1% to 78.0% reported.1,3 Acute kidney injury is associated with disease severity and is more common in those critically ill. The etiology is likely multifactorial and may include dehydration, direct kidney tubular injury by viral infection, thrombotic processes, collapsing glomerulopathy, and rhabdomyolysis.S28,S29 The proportion of critically ill patients with COVID-19 requiring RRT ranges from 15% to 35%.1, 3,S2,S3

There are anecdotal reports of RRT circuit clotting in patients with COVID-19, but few published data supporting this.6 In a multicenter French cohort of 150 patients, 29 were receiving RRT. Of those, 28 (97%) experienced circuit thrombosis, with reduced circuit lifespan compared with a matched historical cohort.3 Circuit anticoagulation was not specifically reported; however, all patients received at least thromboprophylaxis with 30% receiving therapeutic heparin. In a further single-center study of 69 critically ill patients with COVID-19, 9 of 11 patients were escalated to therapeutic UFH infusions due to recurrent circuit thrombosis.S30 A third single-center study reported filter circuit clotting in 8 of 12 critically ill patients with COVID-19 on hemofiltration, despite prophylactic dose anticoagulation.5 This led to escalation to therapeutic anticoagulation with UFH infusion, with 2 of 8 having recurrent filter thrombosis. Of the 4 patients with no filter thrombotic event, 3 were on therapeutic UFH infusion for a preexisting thrombosis at time of initiation of hemofiltration.

National guidance published in England acknowledges the hypercoagulable state associated with COVID-19 and suggests the following actions in the event of frequent circuit clotting: optimizing vascular access, consideration of alternate/combined anticoagulation strategies including combined citrate and heparin (systemic or via circuit), heparin and epoprostenol or argatroban, along with excluding other prothrombotic disorders.6 An Italian group recommend regional citrate as the preferred anticoagulant, and based on their experience suggest a post filter ionized calcium of 0.25 to 0.35 mmol/l (over usual target of 0.3–0.45 mmol/l) to prolong filter patency. For low molecular weight heparin, they suggest a starting dose of 3.5 mg/h with a target systemic anti-factor Xa of 0.25 to 0.35 IU/ml and for UFH 10 to 14 unit/kg per hour targeting an activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) of 60 to 90 seconds. They acknowledge these targets as indicators based on their experience with the need to individually tailor. Approaches to anticoagulation to prolong haemofilter patency are summarized in Figure 1.7

Figure 1.

Approaches to maintaining hemofilter patency, with modifications for those with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; UFH, unfractionated heparin. ∗Monitoring range should be locally determined, suggested by Ronco et al.7

Monitoring UFH with APTT in any inflammatory state may not reflect underlying anticoagulant activity. APTT measures the time to initial clot formation following addition of calcium and an activator of the intrinsic pathway. High Factor VIII and fibrinogen can therefore shorten the APTT in vitro, without affecting the in vivo anticoagulant activity measured with an anti-Factor Xa assay.S31 Other studies demonstrate using an anti-Factor Xa assay facilitates reaching target anticoagulant activity sooner with fewer infusion rate changes.S32,S33 Centers have therefore moved toward monitoring UFH with an anti-Factor Xa assay.S34 Heparin resistance, defined as high-dose UFH (>35,000 units per day to achieve target APTT ratio or inability to do so) is a recognized phenomenon and is often due to raised coagulation factors such as Factor VIII and/or fibrinogen, and/or reduced antithrombin. Small case series describe heparin resistance in critically ill patients with COVID-19 and this may contribute to circuit issues. Beun et al.S35 described 4 patients with COVID-19 infection with heparin resistance (from 75 patients admitted to ICU; the number on therapeutic anticoagulation was not reported). Factor VIII, fibrinogen, and D-dimer were markedly high with normal antithrombin activity. A further group studied 69 critically ill patients with COVID-19 and reported evidence of heparin resistance in 8 of 10 patients on therapeutic UFH infusions.S30

Argatroban has been proposed as an alternate strategy given it exerts its anticoagulant effect independent of antithrombin, by direct thrombin inhibition. A small case series of 10 critically ill patients with COVID-19 confirmed thrombosis and heparin resistance were switched to argatroban therapy following confirmation of antithrombin deficiency.S36 No patient had a further thrombotic event but 3 patients experienced bleeding complications (hemorrhagic stroke transformation, rectal artery bleeding requiring embolization, and haemorrhoidal bleeding resolved on temporary interruption of argatroban infusion).

Managing Demand for RRT During COVID-19

Recurrent circuit thrombosis not only affects individual patient clinical course as outlined previously but may also affect provision of effective hemofiltration in the ICU setting. Because of demand at the peak of the pandemic, many centers were forced to adapt hemofiltration protocols to expand RRT capacity. Optimizing circuit anticoagulation to prolong circuit lifespan is an important measure to preserve consumables. Other strategies recommended included increasing procurement supply (but avoiding hoarding), reducing blood flow to minimize citrate consumption, moderating intensity to conserve fluids, or running accelerated filtration at higher clearance to increase number of patients per machine (providing there are no issues with consumable supply).S37 Early transition to intermittent hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis also should be considered in those patients who are deemed suitable.S38

Future Directions

Multiple international guidelines now recommend all patients hospitalized with COVID-19 receive thromboprophylaxis unless contraindicated.8,9 Randomized controlled trials to evaluate escalated dosing for thromboprophylaxis are in progress, which will enhance prevention of COVID-19–associated VTE (currently 15 studies listed on ClinicalTrials.gov, accessed June 28, 2020). Meta-analyses of RRT anticoagulation strategies and improved understanding of the complex pathophysiology of this novel coagulopathic state will be needed to determine the optimal approach for managing critically unwell patients with COVID-19.

Disclosure

CS has been a consultant for Novartis Pharmaceuticals and speaker for Napp Pharmaceuticals. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary References.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Hirsch J.S., Ng J.H., Ross D.W. Acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;98:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helms J., Tacquard C., Severac F. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1089–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Argenziano M.G., Bruce S.L., Slater C.L. Characterization and clinical course of 1000 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York: retrospective case series. BMJ. 2020;369:m1996. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connors J.M., Levy J.H. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135:2033–2040. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Samkari H., Karp Leaf R.S., Dzik W.H. COVID and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS-CoV2 infection. Blood. 2020;136:489–500. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence COVID-19 rapid guideline: acute kidney injury in hospital. 2020. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng175/resources/covid19-rapid-guideline-acute-kidney-injury-in-hospital-pdf-66141962895301 Available at: [PubMed]

- 7.Ronco C., Reis T., Husain-Syed F. Management of acute kidney injury in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:738–742. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spyropoulos A.C., Levy J.H., Ageno W. Scientific and Standardization Committee Communication: clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;8:1859–1864. doi: 10.1111/jth.14929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moores LK, Tritschler T, Brosnahan S, et al. Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report [e-pub ahead of print]. Chest. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.559. Accessed June 6, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.