Significance

The use of plant biomass for the production of fuels and chemicals is of critical economic and environmental importance, but has posed a formidable challenge, due to the recalcitrance of biomass to deconstruction. We report direct experimental and computational evidence of a simple physical chemical principle that explains the success of mixing an organic cosolvent, tetrahydrofuran, with water to overcome this recalcitrance. The hydrophilic and hydrophobic biomass surfaces are solvated by single-component nanoclusters of complementary polarity. This principle can serve as a guide for designing even more effective technologies for solubilizing and fractionating biomass. The results further highlight the role of nanoscale fluctuations of molecular solvents in driving changes in the structure of the solutes.

Keywords: biomass, pretreatment, solvents

Abstract

A particularly promising approach to deconstructing and fractionating lignocellulosic biomass to produce green renewable fuels and high-value chemicals pretreats the biomass with organic solvents in aqueous solution. Here, neutron scattering and molecular-dynamics simulations reveal the temperature-dependent morphological changes in poplar wood biomass during tetrahydrofuran (THF):water pretreatment and provide a mechanism by which the solvent components drive efficient biomass breakdown. Whereas lignin dissociates over a wide temperature range (>25 °C) cellulose disruption occurs only above 150 °C. Neutron scattering with contrast variation provides direct evidence for the formation of THF-rich nanoclusters (Rg ∼ 0.5 nm) on the nonpolar cellulose surfaces and on hydrophobic lignin, and equivalent water-rich nanoclusters on polar cellulose surfaces. The disassembly of the amphiphilic biomass is thus enabled through the local demixing of highly functional cosolvents, THF and water, which preferentially solvate specific biomass surfaces so as to match the local solute polarity. A multiscale description of the efficiency of THF:water pretreatment is provided: matching polarity at the atomic scale prevents lignin aggregation and disrupts cellulose, leading to improvements in deconstruction at the macroscopic scale.

Plant biomass is a plentiful and inexpensive feedstock for isolating green chemical and fuel precursors to serve future bioindustries. Full valorization of this “vegetable goldmine” requires understanding how to efficiently break down and fractionate the biomass to its molecular constituents, which can then be converted to liquid transportation fuels, plastics, carbon fibers, and many other high-value products (1, 2). Deconstruction of biomass is, however, rendered difficult by its heterogeneous and complex structure. At the molecular level, biomass is made of partially crystalline cellulose fibers that are laminated with lignin and a polysaccharide matrix, containing hemicelluloses and pectins (3). The molecular constituents are chemically complex. For example, cellulose fibers have both polar and nonpolar surfaces (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), depending on the degree of exposure to the solvent of the cellulose hydroxyl groups (4). While, due to its dominant aromatic rings, lignin is hydrophobic overall, it also contains polar hydroxyl groups (5), and its chemical structure is highly heterogeneous, comprising various monomeric units connected with a variety of covalent linkages. Hemicelluloses and pectins are made of a manifold of backbone and side-chain monomers, with their chemical composition determining their functional role (3). These plant biopolymers are organized spatially to form an intricate and robust hierarchical microarchitecture (6) that confers on biomass resistance to deconstruction (7).

The sturdy structure of biomass arises, in part, from the organization of both the polar and nonpolar constituents and from their interaction with the aqueous environment of the plant cell wall. Cellulose fibers are stabilized by hydrogen bonds leading to chains organizing into sheets and by hydrophobic stacking of the sheets to form fibrils (8, 9). Similarly, lignin adopts collapsed conformations in aqueous solution, which contributes to its function in providing rigidity to cell walls (10). Due to the presence of polar groups the lignin collapse differs fundamentally from that of a purely hydrophobic polymer (5, 8). Reversing the above fundamental physicochemical effects, and solubilizing biomass, has therefore been nontrivial.

Thermochemical pretreatments using a variety of chemicals have been employed to enhance biomass deconstruction and fractionation (8). Although the effects of each pretreatment method on biomass differ, the overall aim is to deconstruct biomass components and to fractionate them so that they can be separately processed. This is achieved by disrupting biomass structure across multiple length scales relevant to the organization of the biopolymers, from nanometers to micrometers. Common factors that have been shown to improve biomass deconstruction under various pretreatment technologies include lignin removal and reduction of cellulose crystallinity (11).

A variety of chemicals such as, but not limited to, dilute acids (12), ammonia (13), ionic liquids (14), and deep-eutectic solvents (15) have shown some efficacy in deconstructing biomass. However, it has recently been shown that the use of multifunctional cosolvents provides a particularly effective and economic route to solubilizing plant cell walls and presenting the products in a form convenient for subsequent conversion into biofuels and other high-value products. Examples of these cosolvents are γ-valerolactone (16), aromatic acids (17), and tetrahydrofuran (THF) (18). The organic solvents are typically combined with dilute acid, which removes hemicellulose and pectin through dissolution and depolymerizaton. However, the effect of the pretreatment on the nanoscale architecture of biomass and the role the cosolvents play in solubilizing lignin and cellulose are not well understood.

Here, we examine in detail the interactions with biomass of a cosolvent mixture of water and THF, a polar aprotic cyclic ether. The mixture has been previously shown to significantly improve cellulose saccharification, optimize hemicellulose hydrolysis (19), produce high ethanol titers favorable for economical biofuel production (20), and efficiently fractionate biomass by solubilizing and depolymerizing the lignin (21). Contrast-enabled neutron scattering complemented by molecular-dynamics simulations provide direct experimental and computational evidence that THF forms nanoclusters on nonpolar cellulose surfaces and that it preferentially associates with lignin, while water preferentially solvates cellulose polar surfaces. Changes to biomass structure are analyzed in real time and as a function of temperature for four solvents: water, dilute acid, THF:water, and THF:dilute acid. Use of THF and water cosolvents lead to lignin disaggregation at all temperatures studied (25–150 °C) and additionally to cellulose fiber disruption above ∼150 °C, correlating well to reported experimental results. We establish that, despite the complexity of biomass, the physical changes that lead to its efficient fractionation and deconstruction can be understood by the simple physicochemical concept of preferential solvation of biomass surfaces of matching polarity.

Results

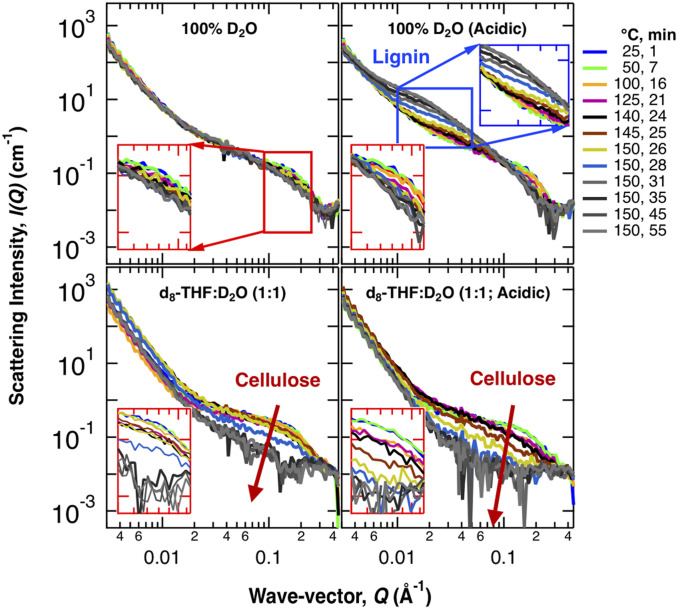

In situ small-angle neutron-scattering (SANS) data were collected from poplar wood as it was being pretreated to 150 °C in four solvents: water (D2O), dilute acid, THF-water, and THF-dilute acid. SANS probes structural changes on the ∼10–1,000-Å scale: the high-Q region (Q > 0.08 Å−1) probes cellulose fibril morphology, while the mid-Q region (0.007 > Q > 0.08 Å−1) reflects changes in lignin aggregation (12).

Water-only pretreatment induced only minor changes in biomass structure, as evidenced by the similarity of the SANS intensities (Fig. 1A). Dilute acid leads to an increase of the intensity in the mid-Q range that corresponds to lignin aggregation (Fig. 1B) (22). The lignin aggregation feature is first observed at ∼100 °C, but becomes more prominent only after the biomass is held at ∼150 °C. In contrast to the aqueous pretreatments, in THF:water lignin aggregation is not observed at any temperature (Fig. 1 C and D). Additionally, the use of water/THF cosolvent also leads to a decrease in the intensity of the high-Q shoulder above ∼150 °C, suggesting it disrupts cellulose fiber structure (Fig. 1C). Addition of dilute acid to the cosolvent accelerates the disruption of cellulose (Fig. 1D): the SANS profile after 24 min (140 °C) with acid is similar to that after 28 min (150 °C) without acid. Use of THF leads to two morphological changes, lignin dissolution and disruption of the cellulose fiber structure, that increase cellulose accessibility.

Fig. 1.

In situ SANS profiles of poplar wood subjected to different solvent pretreatments. SANS data collected while a poplar wood chip was pretreated. The temperature of the reaction cell was increased at a rate of 5 °C/min to 150 °C and held at this temperature for 30 min. The colors indicate the temperature of the reaction cell and the time passed since pretreatment begun. Arrows indicate changes in the SANS profiles associated with the cellulose and lignin. (Insets) I(Q) at relevant Q ranges: red boxes zoom-in the high-Q region associated with cellulose, while blue boxes zoom-in the mid-Q region associated with lignin.

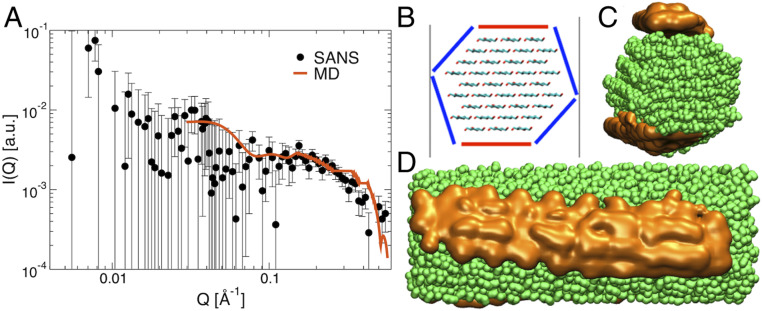

Through the use of contrast variation, neutron scattering has the unique ability of visualizing individual components of a complex biological system. To rationalize the changes observed in the complex biomass material, we measured excess SANS scattering from partially deuterated bacterial cellulose (23) in a THF-water cosolvent and compared with cellulose in water (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). In both these measurements, contrast matching was applied, with the solvents deuterated at the appropriate level to match out the scattering of the cellulose. The expectation for a system with a homogeneously mixed (monophasic) solvent is to observe a flat SANS profile, at least in the high-Q region (and this was observed in an aqueous solvent; see SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Strikingly, however, a feature is found at Q ∼ 0.2 Å−1 for cellulose in contrast-matched cosolvent, which indicates there are nanosized (Rg ∼ 5.5 Å) heterogeneities in the THF:water sample, the neutron-scattering density of which does not match that of the bulk cosolvent (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

SANS and MD simulations of cellulose in THF:water cosolvent. (A) Excess SANS obtained by subtracting the signal of contrast-matched partially deuterated bacterial cellulose in 85:15 D2O:H2O from contrast-matched bacterial cellulose in a cosolvent of d8-THF:D2O:H2O at 1:1.95:1.05 volume ratio. The experimental SANS are shown as black dots (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) and simulations as a red line. The simulation-derived intensities have been scaled by a constant factor to match experiments at low Q. (B) Surfaces of cellulose fiber classified as nonpolar (red) and polar (blue). (C and D) Isosurfaces in which THF (orange) concentration is 3× higher than bulk, viewed perpendicular (C) and parallel (D) to the cellulose fiber(green) axis. SANS and MD were conducted at 25 °C and at the same THF:water vol/vol ratios. All data were collected at 25 °C.

The origin of the excess scattering was revealed by molecular-dynamics (MD) simulations to be nanoscale solvent clusters (24, 25) in which the local concentration of THF (the number of molecules per unit volume) is substantially larger/smaller (at least 3× larger/smaller) than bulk (Fig. 2 B–D). The simulations were validated by a comparison to the experimental data of theoretical SANS intensities calculated from the simulation (Fig. 2A). The THF-rich nanoclusters are localized on the nonpolar cellulose surfaces. Similar, water-rich nanoclusters form on the polar cellulose surfaces, which also contribute to the measured SANS signal. Thus, there exists a complementarity between the polarity of the solvent nanoclusters and the surfaces they solvate. The measurements in Fig. 2 were performed at 25 °C and at a 1:3 THF:water ratio. However, MD simulations have found the nanoclusters at conditions representative of Fig. 1: equivolume THF:water ratio and temperatures up to 175 °C (24).

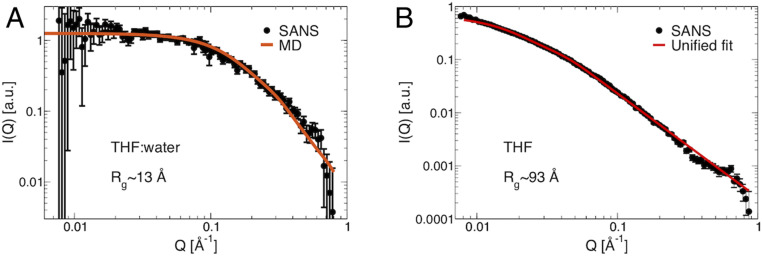

We also measured SANS of lignin isolated from poplar and found the solvent to have a profound effect on its molecular conformations. In D2O, lignin collapses and forms macroscopic aggregates that are not permeated by the solvent. In comparison, d8-THF:D2O is found here to be a θ-solvent for lignin, i.e., in which lignin–lignin and lignin–solvent interactions balance leading to lignin adopting random coil conformations with an Rg ∼ 13 Å (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S3) (8, 26). A Debye-coil model (SI Appendix, Eq. S1), which assumes an individually solvated and dispersed random coil, indeed provides a good fit to the d8-THF:D2O SANS data (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

Fig. 3.

SANS and MD simulations of lignin in THF:water cosolvent and in pure THF. SANS of acetylated lignin (10 mg/mL) extracted from poplar in A. A cosolvent of d8-THF:D2O (1:1 v:v), black dots are the experimental data and the red line the MD simulation. The simulation-derived intensities have been scaled by a constant factor to match experiments at low Q. (B) d8-THF, black dots are experimental data and the red line is a unified fit (SI Appendix, Eq. S2). See also SI Appendix, Fig. S3. All data were collected at 25 °C.

In pure THF the position of the SANS shoulder is found at a lower Q as compared to lignin in the cosolvent. The Rmin obtained from the unified fit (27) to the data, in which the scattering intensity is represented as the sum of Guinier’s exponential form and a power-law regime (SI Appendix, Eq. S2 and Fig. S3), is the lower bound of the particle dimension. The unified fit results indicate an Rg Rmin = 93 Å of the lignin aggregates, but the exact particle size cannot be obtained. Nonetheless the Rmin is found here to be greater than that of a single lignin coil (Rg 13 Å), suggesting it arises from multiple lignin molecules associating to form a larger “assembly.” A unified fit (27) to the data (SI Appendix, Eq. S2 and Fig. S3) finds the configurations of the assembly in THF to be random coils, as indicated by an ∼ Q−2 power-law dependence of the SANS in the mid-Q region (SI Appendix, Fig. S3): The Q−2 scaling is consistent with a Gaussian fractal chain, equivalent to a random coil in θ-solvent conditions (28), although the precise origin of the scattering cannot be unequivocally inferred from the experiments alone. The assembly revealed by SANS can thus be considered as rodlike aggregates of entangled lignin molecules (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) that are organized in a random-coil configuration. Comparing Fig. 3 A and B we conclude that addition of water to THF breaks the lignin assembly without changing the random-coil configurations of the individual lignin molecules.

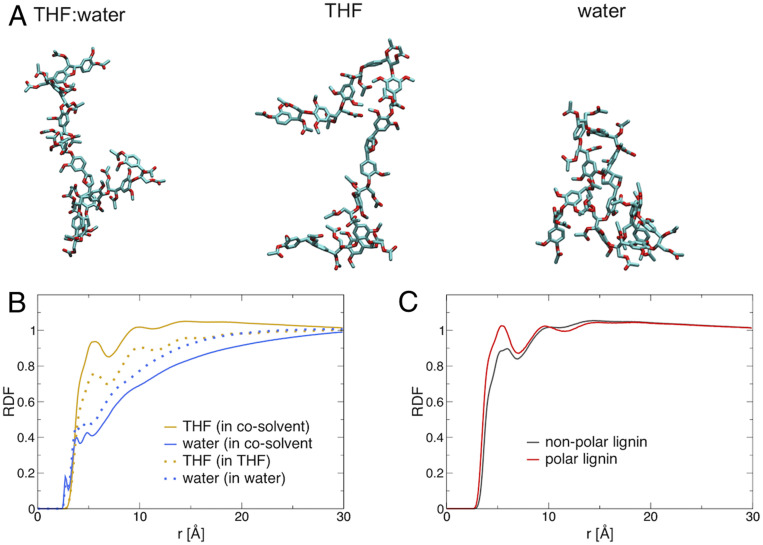

An explanation of the above changes is provided by MD simulations of a single lignin molecule in the three solvents. The reliability of the MD is confirmed by the good agreement found between simulation-derived and experimental SANS intensities for lignin in THF:water (Fig. 3A). Whereas lignin is collapsed in water, it assumes coil conformations in both pure THF and the cosolvent (Fig. 4A). The lignin Rg was found to decrease with addition of water: Rg = 14.1 ± 0.3 Å in THF, Rg = 13.0 ± 0.1 Å in THF:water, and Rg = 10.0 ± 0.4 Å in water. The conformation of lignin is found here to be influenced by its local solvation: THF is found to preferentially solvate the lignin in the cosolvent, the local number concentration (number of molecules per unit volume) of THF being ∼2× larger on the lignin surface than that of water (Fig. 4B, solid lines). In comparison, THF and water are mixed far from the lignin and have the same bulk number concentration (Fig. 4B). This indicates that the binding of THF to lignin, found not only in pure THF but also in the cosolvent, drives the adoption of the coil conformations.

Fig. 4.

MD simulations of lignin in different solvents. (A) Representative structures from MD simulations of single lignin molecules in three solvents at 25 °C; carbon atoms shown in cyan and oxygen in red. (B) Radial distribution function (RDF), a measure of the local density of a solvent at a distance r from the lignin, between lignin and THF (orange) or water (blue) in either the cosolvent (solid lines) or the pure solvent (dashed lines). (C) RDF in the cosolvent environment between THF atoms and polar lignin atoms, defined here as having a partial charge |q| > 0.3 (red) or nonpolar, with |q| < 0.3, (red) atoms. Data are normalized to 1 at large distances. All RDFs are calculated with respect to nonhydrogen atoms of both lignin and the solvents.

Further, THF is found to have a lower number concentration close to polar atoms of lignin (defined as having a particle charge |q| < 0.3) than around the less polar atoms (Fig. 4C). In this manner, the solvation of lignin and cellulose are similar in that complementarity is found between the polarity of the biopolymer and the solvents around it. Although the data of Figs. 3 and 4 were obtained at 25 °C, previous MD simulations have shown the preferential solvation of lignin by THF to occur at temperatures up to 170 °C (29), i.e., at temperatures at which the experiments in Fig. 1 were conducted.

MD simulations of lignin in THF and THF:water find that, although lignin adopts coil conformations in both solvents, the intermolecular lignin contacts (SI Appendix, Fig. S6) are almost 4× more numerous in THF (34 ± 8) than in THF:water (9 ± 4). These simulation results are only qualitatively consistent with the SANS observation of a supramolecular assembly of lignin in THF but not in THF:water (Fig. 3). We note that kinetic barriers could lead to lignin association on times longer than 250 ns that are not captured here.

Discussion

The complexity of plant biomass, manifested across multiple scales from plant ultrastructure to molecular and chemical features, contributes significantly to its recalcitrance to chemical and biological deconstruction. Recent studies demonstrate that adding THF as a lower-polarity cosolvent to water in combination with a dilute acid catalyst can effectively overcome this recalcitrance at lower severity reactions. This cosolvent mixture can completely solubilize plant polysaccharides and solubilize 90% of the lignin, leaving only nonrecalcitrant structural lignin behind. However, the molecular-level mechanism by which the two solvent components drive efficient biomass deconstruction has not been understood.

Using MD simulation aided by neutron scattering, we detail mechanistic evidence of biomass disruption during THF cosolvent pretreatment and elucidate the molecular driving forces involved. Use of THF disrupts the cellulose fiber structure and prevents the undesirable aggregation of lignin. By comparing temperature-resolved measurements performed in water, dilute acid, THF:water, and THF:dilute acid we find that the lack of lignin aggregation is observed over a wide temperature range studied here (25–150 °C), with and without acid. Interestingly, the THF:water cosolvent is found to prevent interlignin association more than pure THF does (Fig. 3). This finding may explain why mixtures of organic solvents with water lead to higher delignification of biomass than their pure organic solvent counterparts (30), and why addition of water to lignin solubilized in THF leads to the formation of lignin nanoparticles (31). In contrast to lignin, cellulose disruption occurs only above ∼150 °C and occurs earlier in the pretreatment if dilute acid is added. The above suggest that the severity of THF cosolvent reaction on biomass has a differential effect on lignin solubilization and cellulose disruption, enabling greater processing versatility. Low-severity pretreatments may be effective when fractionation of biomass is prioritized over deconstruction.

The disassembly of the amphiphilic biomass is enhanced because the solvents demix near biomass elements to locally match the polarity of the solutes with the solvents. Although simulations have predicted localization of organic solvents near biomass polymers (24, 29, 32–34), we provide here direct experimental evidence of this demixing in the form of THF nanoclusters localized on the cellulose nonpolar surfaces (Fig. 2) and near the hydrophobic lignin by THF (Fig. 4), and of water-rich nanoclusters near the polar cellulose surfaces (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the size of the nanoclusters was determined to be Rg ∼ 0.5 nm. In addition, the validation of the MD simulations by comparison to neutron scattering (Figs. 2 and 3) indicates the accuracy of the simulations employed.

The presence of solvent clusters has been previously reported in binary mixtures of organic solvents and water (35). For THF:water, previous SANS studies have found discrete water and THF clusters in THF:water vol/vol 2:1 ratio (36). Further, in contrast to what is reported here for lignin, the presence of nanoclusters in THF:water coincides with reduced solubility of polyN-isopropylacrylamide (PNIPAM). PNIPAM has favorable interactions with both THF and water, while for the lignin system only the lignin–THF interactions are favorable. Therefore, solvent nanoclusters in binary mixtures may lead to loss of solubility in the cases when both pure solvents are good solvents for a polymer.

Based on the above results we suggest the desirable physical chemical features of THF that render it an efficient pretreatment solvent. THF, an aprotic organic solvent (37), is polar enough to be miscible with water, but not too polar to prevent its association with the hydrophobic elements of biomass. Further, the roughly planar geometry of THF molecules assists interactions with the relatively flat cellulose nonpolar surfaces (24) and we speculate that the planarity of THF may also facilitate its interaction with the lignin aromatic rings. We also suggest that favorable interactions with cellulose are an important aspect of efficient organic pretreatment solvents, in addition to their widely recognized ability to dissolve lignin.

We examined here THF as a pretreatment solvent, but the above mechanisms may be more broadly in play in pretreatments involving other aprotic polar solvents, such as γ-valerolactone (16), dioxane (38), acetone (39), and dimethyl sulfoxide (40), which promote delignification and are generally important for valorizing biomass by fractionating it into its components with high purity (41). Although we focus here on physical changes, localization of polar solvents may also enhance chemical reactivity (33). For example, the local segregation of solvents has been previously found to increase the chemical hydrolysis of cellulose (24) and enhance the rates of acid-catalyzed biomass dehydration reactions (42).

The presence of nanoclusters in mixed solvents has been shown to drive other interesting phenomena. For example, the complex behavior of polymer coils in a binary solvent near the critical temperature of demixing has been attributed to microphase separation of the solvent inside the polymer coil (43). It is therefore becoming apparent that meso/nanoscale fluctuations of molecular fluids can drive major changes in the dimensions and organizations of macromolecular solutes.

In conclusion, by combining neutron scattering and molecular simulation, we have obtained direct evidence of water and THF, which are miscible in bulk, demixing on amphiphilic biomass substrates. We further reveal that locally matching the polarity of solutes and solvents leads to two molecular-level processes, disruption of cellulose and prevention of lignin aggregation, that drive the morphological changes in biomass during THF:water pretreatment. By comparing temperature-resolved pretreatment of poplar wood performed in water, dilute acid, THF:water, and THF:dilute acid we find these two processes have a different dependence on temperature and acidity. We provide mechanistic details connecting atomic-scale solvation to mesoscale changes that take place during the facile deconstruction and fractionation of the complex biomass material. The inclusion of a solvent of modest polarity, polar enough to mix with water but not too polar to prevent interaction with hydrophobic biomass elements, is suggested as a potent pretreatment component to destabilize the assembly of biomass that has evolved to be highly recalcitrant in aqueous conditions. Although the complexity and heterogeneity of the biomass make its deconstruction difficult, simple hydrophobicity concepts can explain the efficiency of solvent-based pretreatment. These concepts can be employed to tune pretreatment technologies that maximize deconstruction of biomass and facilitate the separation of its components for upgrading to energy and materials. These results, when put in the context of nanoscale fluctuations, suggest that nanoclusters in the mixed solvent act as a driving force behind changes in the structure of macromolecular solutes.

Materials and Methods

Samples.

Three types of sample were prepared: 1) intact and milled wood chips of poplar, a promising bioenergy feedstock; 2) lignin isolated from poplar and subsequently acetylated (44); and 3) partially deuterated bacterial cellulose, prepared by growing the Acetobacter xylinus subsp. sucrofermentans bacteria in a D2O-based growth media with hydrogenated glycerol. The neutron contrast-match point of the cellulose is 85:15 D2O:H2O (23).

SANS.

SANS data were collected at the Bio-SANS instrument located at the High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) facility at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (45, 46). Three main types of SANS experiments were performed, a reaction, a contrast variation, and a regular SANS study. For the reaction study, in situ SANS measurements were performed during thermochemical pretreatment of poplar wood chips in a reaction cell (46) using four different solvents: 1) D2O; 2) dilute acid (0.05 M H2SO4) in D2O; 3) 1:1 (v:v) D2O: d8-THF; and 4) dilute acid (0.05 M H2SO4) in 1:1 (v:v) D2O: d8-THF. The temperature of the reaction cell was raised at the rate of 5 °C/min to 150 °C and kept at this temperature for 30 min. For the contrast-matching SANS study, partially deuterated bacterial cellulose (1 mg/mL) was measured in two different contrast-matching solvents: 1) 85:15 (v:v) D2O:H2O; and 2) a 1:3 (v:v) mixture of d8-THF:aqueous mixture of 65:35 (v:v) D2O:H2O (i.e., d8-THF:D2O:H2O 1:1.95:1.05 v:v). The overall scattering length densities of these solvents are the same. Banjo Hellma cells with 1-mm path length were used for these measurements. Finally, SANS data of acetylated lignin (10 mg/mL) in three solvents, 1) D2O; 2) d8-THF; and 3) 1:1 (v:v) D2O: d8-THF, were collected. Since lignin is not entirely soluble in these collections of solvents, detachable wall titanium cells with 1-mm spacer were used for these measurements.

MD Simulations.

A 36-chain cellulose Iβ fibril (degree of polymerization 20) solvated in 3:1 THF:water (v:v) and in pure water. Five independent simulations were run for each solvent condition, 100 ns each. SASSENA (47) was employed for the calculation of SANS profiles, and were assigned the appropriate atomic scattering length densities to match the experimental deuteration conditions; see SI Appendix, Methods. Molecular models representative of acetylated poplar lignin were built based on experimentally determined average chemical composition data (48). Two systems, one containing a single molecule and the other containing three initially separated molecules, were simulated in three solvents: water, THF, and 1:1 THF:water (v:v). The MD models were assigned the appropriate atomic scattering length densities to match the experimental deuteration conditions. All simulations were performed at 25 °C, using GROMACS and employing CHARMM force-field parameters and the TIP3P water model (49–52).

Data Availability.

The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Oak Ridge National Laboratory webpage. Scripts for the computational analysis are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Genomic Science Program, Office of Biological and Environmental Research (OBER), Office of Science, US Department of Energy (DOE), under Contract FWP ERKP752. C.M.C. was supported by the OBER through the Center for Bioenergy Innovation, managed by Oak Ridge National Laboratory. This research used resources of two DOE Office of Science User Facilities: The HFIR at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility. Oak Ridge National Laboratory is managed by UT-Battelle, LLC, for the US DOE under Contract DE-AC05-00OR22725. This manuscript has been authored by UT-Battelle, LLC under Contract DE-AC05-00OR22725 with the US DOE. The United States Government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the United States Government retains a nonexclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for United States Government purposes. The DOE will provide public access to these results of federally sponsored research in accordance with the DOE Public Access Plan (https://energy.gov/downloads/doe-public-access-plan).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1922883117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rinaldi R. et al., Paving the way for lignin valorisation: Recent advances in bioengineering, biorefining and catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 8164–8215 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grossman A., Vermerris W., Lignin-based polymers and nanomaterials. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 56, 112–120 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cosgrove D. J., Jarvis M. C., Comparative structure and biomechanics of plant primary and secondary cell walls. Front. Plant Sci. 3, 204 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gross A. S., Chu J.-W., On the molecular origins of biomass recalcitrance: The interaction network and solvation structures of cellulose microfibrils. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 13333–13341 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petridis L., Smith J. C., Conformations of low-molecular-weight lignin polymers in water. ChemSusChem 9, 289–295 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tetard L., Passian A., Farahi R. H., Thundat T., Davison B. H., Opto-nanomechanical spectroscopic material characterization. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 870–877 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chundawat S. P. S. et al., Multi-scale visualization and characterization of lignocellulosic plant cell wall deconstruction during thermochemical pretreatment. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 973–984 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petridis L., Smith J. C., Molecular-level driving forces in lignocellulosic biomass deconstruction for bioenergy. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 382–389 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergenstrahle M., Wohlert J., Himmel M. E., Brady J. W., Simulation studies of the insolubility of cellulose. Carbohydr. Res. 345, 2060–2066 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Q., Luo L., Zheng L., Lignins: Biosynthesis and biological functions in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 335 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao X. D. et al., Comparison of enzymatic reactivity of corn stover solids prepared by dilute acid, AFEX (TM), and ionic liquid pretreatments. Biotechnol. Biofuels 7, 71 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langan P. et al., Common processes drive the thermochemical pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass. Green Chem. 16, 63–68 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sousa L. D. et al., Next-generation ammonia pretreatment enhances cellulosic biofuel production. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 1215–1223 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 14.George A. et al., Design of low-cost ionic liquids for lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment. Green Chem. 17, 1728–1734 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu G. C., Ding J. C., Han R. Z., Dong J. J., Ni Y., Enhancing cellulose accessibility of corn stover by deep eutectic solvent pretreatment for butanol fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 203, 364–369 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luterbacher J. S. et al., Nonenzymatic sugar production from biomass using biomass-derived gamma-valerolactone. Science 343, 277–280 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen L. et al., Rapid and near-complete dissolution of wood lignin at </=80 degrees C by a recyclable acid hydrotrope. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701735 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai C. M., Zhang T., Kumar R., Wyman C. E., THF co-solvent enhances hydrocarbon fuel precursor yields from lignocellulosic biomass. Green Chem. 15, 3140–3145 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith M. D., Cai C. M., Cheng X., Petridis L., Smith J. C., Temperature-dependent phase behaviour of tetrahydrofuran-water alters solubilization of xylan to improve co-production of furfurals from lignocellulosic biomass. Green Chem. 20, 1612–1620 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen T. Y., Cai C. M., Kumar R., Wyman C. E., Overcoming factors limiting high-solids fermentation of lignocellulosic biomass to ethanol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 11673–11678 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patri A. S. et al., A multifunctional cosolvent pair reveals molecular principles of biomass deconstruction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 12545–12557 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pingali S. et al., Morphological changes in the cellulose and lignin components of biomass occur at different stages during steam pretreatment. Cellulose 21, 873–878 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 23.He J. H. et al., Controlled incorporation of deuterium into bacterial cellulose. Cellulose 21, 927–936 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mostofian B. et al., Local phase separation of Co-solvents enhances pretreatment of biomass for bioenergy applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 10869–10878 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith M. D., Cheng X., Petridis L., Mostofian B., Smith J. C., Organosolv-water cosolvent phase separation on cellulose and its influence on the physical deconstruction of cellulose: A molecular dynamics analysis. Sci. Rep. 7, 14494 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith M. D., Mostofian B., Petridis L., Cheng X., Smith J. C., Molecular driving forces behind the tetrahydrofuran–Water miscibility gap. J. Phys. Chem. B 120, 740–747 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beaucage G., Approximations leading to a unified exponential power-law approach to small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Cryst. 28, 717–728 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beaucage G., “Combined small-angle scattering for characterization of hierarchically structured polymer systems over nano-to-micron meter: Part II theory” in Polymer Science: A Comprehensive Reference, Matyjaszewski K., Möller M., Eds. (Elsevier BV, Amsterdam, 2012), Vol. 2, pp. 399–409. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith M. D. et al., Cosolvent pretreatment in cellulosic biofuel production: Effect of tetrahydrofuran-water on lignin structure and dynamics. Green Chem. 18, 1268–1277 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xue Z. M., Zhao X. H., Sun R. C., Mu T. C., Biomass-derived gamma-valerolactone-based solvent systems for highly efficient dissolution of various lignins: Dissolution behavior and mechanism study. ACS Sustain. Chem.& Eng. 4, 3864–3870 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lievonen M. et al., A simple process for lignin nanoparticle preparation. Green Chem. 18, 1416–1422 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vasudevan V., Mushrif S. H., Insights into the solvation of glucose in water, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), tetrahydrofuran (THF) and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and its possible implications on the conversion of glucose to platform chemicals. RSC Advances 5, 20756–20763 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varghese J. J., Mushrif S. H., Origins of complex solvent effects on chemical reactivity and computational tools to investigate them: A review. React. Chem. Eng. 4, 165–206 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walker T. W. et al., Universal kinetic solvent effects in acid-catalyzed reactions of biomass-derived oxygenates. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 617–628 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takamuku T. et al., Large-angle X-ray scattering, small-angle neutron scattering, and NMR relaxation studies on mixing states of 1,4-dioxane-water, 1,3-dioxane-water, and tetrahydrofuran-water mixtures. J. Mol. Liq. 103–104, 143–159 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hao J., Cheng H., Butler P., Zhang L., Han C. C., Origin of cononsolvency, based on the structure of tetrahydrofuran-water mixture. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154902 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X., Rinaldi R., Solvent effects on the hydrogenolysis of diphenyl ether with Raney nickel and their implications for the conversion of lignin. ChemSusChem 5, 1455–1466 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.An S. et al., A two-stage pretreatment using acidic dioxane followed by dilute hydrochloric acid on sugar production from corn stover. RSC Advances 7, 32452–32460 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smit A., Huijgen W., Effective fractionation of lignocellulose in herbaceous biomass and hardwood using a mild acetone organosolv process. Green Chem. 19, 5505–5514 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mushrif S. H., Caratzoulas S., Vlachos D. G., Understanding solvent effects in the selective conversion of fructose to 5-hydroxymethyl-furfural: A molecular dynamics investigation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 2637–2644 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ragauskas A. J., Lignin “first” pretreatments: Research opportunities and challenges. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 12, 515–517 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mellmer M. A. et al., Solvent-enabled control of reactivity for liquid-phase reactions of biomass-derived compounds. Nat. Catal. 1, 199–207 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng X., Anisimov M. A., Sengers J. V., He M., Unusual transformation of polymer coils in a mixed solvent close to the critical point. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 207802 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoo C. G., Li M., Meng X., Pu Y., Ragauskas A. J., Effects of organosolv and ammonia pretreatments on lignin properties and its inhibition for enzymatic hydrolysis. Green Chem. 19, 2006–2016 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lynn G. W. et al., Bio-SANS–A dedicated facility for neutron structural biology at oak ridge national laboratory. Physica B 385–386, 880–882 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heller W. T. et al., The bio-SANS instrument at the high Flux Isotope reactor of Oak Ridge national laboratory. J. Appl. Cryst. 47, 1238–1246 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindner B., Smith J. C., Sassena–X-ray and neutron scattering calculated from molecular dynamics trajectories using massively parallel computers. Comput. Phys. Commun. 183, 1491–1501 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stewart J. J., Akiyama T., Chapple C., Ralph J., Mansfield S. D., The effects on lignin structure of overexpression of ferulate 5-hydroxylase in hybrid poplar. Plant Physiol. 150, 621–635 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abraham M. J. et al., GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1–2, 19–25 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guvench O., Hatcher E., Venable R., Pastor R., MacKerell A., CHARMM additive all-atom force field for glycosidic linkages between hexopyranoses. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 5, 2353–2370 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jorgensen W., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J., Impey R., Klein M., Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Petridis L., Smith J. C., A molecular mechanics force field for lignin. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 457–467 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Oak Ridge National Laboratory webpage. Scripts for the computational analysis are available upon request from the corresponding author.