Abstract

Business travellers make up a large part of the customer base for the Swedish hospitality industry, accounting for 54% of the occupancy rate of Swedish hotels in 2018. Yet, very little is known about their meal habits while being at the destination of a business trip. This, even though the handling of meals in an environment that is less known to the traveller could add to the complexity of everyday life. Therefore, this study is aimed to explore actions performed by business travellers at the destination of travel as part of their meal practice with the purpose of elucidating the meal habits of this group. The research is theoretically framed within the context of social identity theory and social practice theory. A questionnaire was filled out by 538 Swedish business travellers recruited by means of self-sampling; 77% of the respondents were men, and 77% were above 45 years of age. The majority of the respondents, 67%, travelled over 50 days per annum, and 59% were located in the highest income quartile. The analysis of the data generated a general overview of the actions performed in relation to the meal, while also showing differences in actions taken based on income and gender. Women were significantly more price conscious than men and to a larger extent used technical assistance to find somewhere to eat. When travelling alone they also reported eating faster than at home and bringing back food and eat at the hotel room more often than men did. Men, in contrast, exhibited an inclination towards seeking social contexts to insert themselves in during dinners when travelling alone, as to be able to eat together with other people. The, relatively, lower income group showed more price consciousness as well as used the help of technical assistance to find somewhere to eat.

Keywords: Business travel, Meal science, Sociology of food, Meal habits

Introduction

Each year, 13.3 million hotel nights are bought by the corporate sector in Sweden, according to the official accommodation statistics, which makes up 54% of the total occupancy rate. With each of these overnight stays comes the necessity for the hospitality industry to supply meals for the business travellers. There have, furthermore, been as increase of 1.5 million hotel nights related to business travel in Sweden over the past ten years, hence accounting for a significant share of the domestic hospitality market. However, very little is known about the business travellers’ meals, e.g. the rationale behind the participation in meals qua context, as they have not been the explicit focus within the meal related literature. Therefore, exploration of those meals could be important for service providers within the hospitality industry as well as for food studies researchers.

While being at the destination of their travel, business travellers must rely on the food supply available to them at restaurants and other food outlets for their meals, that are contextually different from the habitual meals. What is more, as meals are an important part of everyday life, managing these meals away from home, in a less known environment, add to the possible complexity of their situation. To handle this emerged complexity business travellers are known to create strategies to handle their work life, e.g. by minimising the time they spend at a destination (Gustafson, 2012b), trying to manage family life while being away from home (Lassen, 2010; Saarenpää, 2016), or by adapting their meal patterns while travelling to better suit their situation and situational identity (Sundqvist et al., 2020).

Meal as part of daily routine

Business travellers are often represented as very busy managers and professionals, with a high degree of autonomy (Aguilera, 2008; Gustafson, 2012a). This does, however, only reflect part of the business traveller work force, as it also includes workers at the operational level such as technicians and construction workers (Aguilera, 2008). Furthermore, there is an on-going and continuous process of normalisation of the business travellers' self-identity, starting in a sense of glamour and ending in a perception of normality (Gustafson, 2014). That is, to a large extent, business travel is not considered to be glamorous by the business travellers themselves, but is rather considered to add to the complexity of everyday life due to factors such as the need to manage work-space on the go (Brown and O'Hara, 2003) difficulties following diets (Lee and McCool, 2008); increased alcohol consumption (Gustafson, 2012b; Rogers and Reilly, 2002), and feelings of neglectance toward the family due to long working hours (Gustafson, 2014; Saarenpää, 2016). That is, being part of a context where the person, due to travelling arrangements does not have the means to carry on habitual practices have e.g. an effect on meal patterns which in turn could affect the health of the person.

Practice, or social practice, in this sense is understood as a set of organised everyday activities. Such meal patterns are found at the cultural level of society and relates to the order in which meals occur during the day and what type of food is eaten during that timeframe (Fjellström, 2004; Mäkelä et al., 1999). The engagement in meals, in Sweden, follow a pattern that is currently made up of three main meals and an in-between meal snack (Lund and Gronow, 2019), where one meal, breakfast, is cold and commonly eaten between six and nine in the morning and two meals are served warm. Lunch is usually eaten between eleven and noon, and dinner between five in the afternoon and seven in the evening (Fjellström, 2004). The three-meal pattern is, in a historical sense, a recent development, traced to the late nineteenth century (Fjellström, 2004). The pattern, when established, seems to get adhered to by the majority of the population and also be resistant to change (Gronow and Jääskeläinen, 2001), a resistance that has also been observed in Great Britain (Warde and Yates, 2017).

This cultural aspect of eating is, furthermore, carried on at the level of the individual as part of an individual's everyday meal practices. While travelling in contexts involving high level of organisation e.g. meetings, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions (MICE), meals are often taken care of by external parties such as travelling agencies, meeting planners, or convention bureaus (Davidson and Cope, 2003). That is, activities where organisers are heavily involved, such as conferences, often include meals as part of the package - leaving individuals with very little, if any, say in what food they are going to be served and with whom they will dine, for the duration of the event, possibly conflicting with their habitual meal pattern. There are, in contrast, also business travellers who travels with less organisational involvement where the plethora of individual expertise becomes visible (Davidson and Cope, 2003). It is within the scope of this individual business travel that, for example, data is gathered for research, houses and roads are built, customers and suppliers are met, technical problems are solved, and knowledge is disseminated. Furthermore, this different level of organiser involvement presents another opportunity regarding the availability of meals.

The process of the meal

Meals are an important part of identity, both at the societal and the individual level (Finkelstein, 2014; Fischler, 1988, 2011; Fjellström, 2004; Warde, 2016; Warde and Martens, 2000). As a consequence, they are also driving activities of people. These activities related to meals could be seen in the leisure traveller using the meal as a means of exploration and discovery (Mak et al., 2012; Quan and Wang, 2004; Williams, 1995). There is however, to our knowledge, no indication in the literature of how business travellers rationalise their meals. Instead it has been stated that “[f]ood study in the tourism social science is simply ignored or taken for granted” (Quan and Wang, 2004, p. 299). Albeit it is an older source and a lot has happened since the paper was published, it still holds true for business travellers’ meals.

It is known that business travellers experience parts of their work situation as stressful because of the necessity to balance work and family life while travelling, and meals are a part of this needed balance (Gustafson, 2012b). Given the meals cultural, societal, and individual importance, studying business travellers' activities related to meals while being away from home, becomes an important first step in understanding the practice of business travellers' meals, as a whole. Furthermore, the meal is a context in which social beings participate, meet, and eat and drink (J. Edwards and Gustafsson, 2008; Gustafsson et al., 2006; Hansen et al., 2005), a context in which contextual understandings give meaning to the entirety of the meal (Sundqvist and Walter, 2017). This contextual meaning is depending on who the experiencer is and with whom the experiencer associates. That is, it is depending on the experiencer's identity. The meal could hence be understood as a collection of contextualised actions, experienced, or understood, on the basis of who the individual experiencing it associates with.

Knowing more about how business travellers practice their meals could thus have societal benefits, such as reducing stress, as well as managerial benefits for the hospitality industry, such as being able to create better value options for the customers. Thus, the aim of this article, as a first step into understanding business travellers’ meal practices, is to explore the actions performed by business travellers at the destination of travel as part of their meal practice.

Understanding the complexity of the notion of the meal, a theoretical framework drawing on both social identity theory and social practice theory have been established to easier grasp, and understand, the actions of the business travellers related to their meals.

Theoretical framework

The choice of theory often comes down to help explaining, what could not be said without it. When studying a group of persons being part of the same social category, or demography, one such theory that could help understand, and conceptualise, the particularities of that group is social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Oyserman, 2009). While social identity theory might help conceptualise, and hence speak about abstract phenomena occurring at the group level, other theoretical approaches are needed to bring this abstraction down to the concrete, everyday consequences of activities related to the phenomena. Social practice theory is one such stream of theoretical conceptualisation that involves everyday activity as the fundament of the social (Schatzki, 1996, Schatzki, 2002, Schatzki, 2012, Schatzki, 2019). Thus, this paper utilise two theoretical streams to conceptualise the group, that is, social identity theory to conceptualise who they are, and social practice theory to bring forth their actions, that is, what they do.. By bringing these theoretical approaches together, we hope to shed light on why they do what they do.

Social identity theory

Tajfel and Turner (1979) state that social groups are constructed from social categories, out of which individuals shape their identities. Social categories exist on a scale between static and dynamic. The static categories, also include high inertial categories e.g. being a mother, belonging to a specific ethnic group, or being a man; whereas, dynamic categories are more fluid e.g. being a business traveller, a CEO, or a vegan. The categories could also be linked to abstract social phenomena, such as being a winner or being fashionable. Tajfel and Turner (1979) argue that being part of a group, an in-group, is defined in relation to the groups that are not part of your identity, the out-groups. In social identity theory the assumption of difference maximization between in-groups and out-groups is important, that is, the groups strive to maximize the difference of possessed scarce resources such as power or wealth between the own group and other groups (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). This differentiation is made visible in certain performances, such as consumption.

The phenomenon of consumption is intrinsically linked with production and not only the production of goods and services but also the production of consumer identities (Firat and Shultz, 1997; Firat and Venkatesh, 1995; Hamouda and Gharbi, 2013). Instead of being stable and closely connected with personality, an identity could be seen as something fragmented, dynamic and contextually shaped (D. Oyserman, 2009). (Reed, 2002) argues that an individual has the opportunity to perform an infinite number of potential social identities based on the understanding of the culture in which the individual acts. These identities, he claims, would be based on any social category within a given culture, that is, any socio-cultural construct could be the base for an identity. This is a contextual take on identity, or identities, sharing some fundamental principles with other views on identity such as the view that identity is a category label to which a person associates by either their own choice or by endowment (Reed et al., 2012). Identity has also been linked to other things than individuals (Schatzki, 2002, p. 52). abstracts something's identity to “what something is, is relative to where it fits into given arrangements.” This does mean that the setting, for example a meal, has its own identity depending on the social setting in which it is experienced; further, it also means that the identity of the meal is experienced by the participants in it, that is, the meal could have different meanings, therefore different identities, depending on the participating individuals. To exemplify, the salient aspect of a meal could be understood as a business meeting by one participant, whereas another participant could view the same meal as a social event.

Within social identity theory, the concept of identity salience is central. When an identity becomes salient it becomes the dominant identity, governing how the individual acts within a specific context. When the individual's identity becomes salient with regards to a specific social group, that group's consumer behaviour will also be practiced by the individual (Oyserman, 2009; Reed, 2002; Reed et al., 2012; Tajfel and Turner, 1979). This would also hold true for social roles as a type of identity (Reed et al., 2012), such as the role of being a business traveller. Being part of a group, or identifying with a specific social category, thus, comes with a set of appropriate consumer behaviour sanctioned by the group. This appropriate behaviour, the doing, or performing of an identity, could be an inherent part of the social practices related to the group membership.

Social practice theory

The notions of practice, social practice and practice theory are widely used within the social sciences of today. This terminology is however, to a degree, mystifying as there are numerous practice theories with their own intrinsic, ontologically different, takes on social practices. This study is framed within the social practice theory as it is conceived within the works of social theorist and philosopher Theodore Schatzki.

Schatzki (1996, 2005, 2012, 2019) conceptualises social practices as the organisation of actions into meaningful activities. One of the more common descriptions of practices is that they are a “temporally unfolding and spatially dispersed nexus of doings and saying” (Schatzki, 1996, p.89).

Since practices in this way are temporally unfolding and spatially dispersed, that is, they have an integrated spatial-temporal aspect. With this, it is implied that practices are performed, or enacted, in physical space and that this performance take place over time. It further relates to the driving of practices through time, that is, as new activities are added to the practice, it's temporal dimension extends (Schatzki, 2002). To exemplify, there are a manifold of activities that make up cooking practices, such as peeling, chopping, sautéing, broiling, reducing, plating, and so on. All these activities occur over time, in relation to the same practice, moreover, they occur at specific places within the realm of physical space, often in a kitchen.

The aforementioned notions, or concepts, relate to qualities of the activities, actions, or doings and sayings, that make up social practices. Doings and sayings are, in a mundane sense, easily discernible as what people do and people say. In theories however, things are seldom as mundane as they first seem. In 2002 (p. 72) Schatzki elaborates on doings and sayings as being bodily by stating that “[b]odily doings and sayings are actions that people directly perform […] not by way of doing something else.” Doings, in this sense, are to be understood as bodily movements that in them carry no meaning, such as tapping the keys of a keyboard, whisking, or jumping. Sayings, however, are a subset of doings; that is, sayings are doings that say something about something. Sayings, though, are not dependent on language, although the relationship is close, waving, pointing, or shrugging are all means of communicating something and, hence, are sayings. In contrast it has been argued that “a doing is always the doing of something” and that “a doing is the performing of an action” which could hint that even doings carry meanings and are not just the performance of basic actions (Schatzki, 2019, p. 28).

The organisation of sayings and doings into practices relates to the ontological foundation of the theory of practice. Schatzki argues that the basis for the study of practices is that the social can only be analysed by studying the sites of human coexistence (Schatzki, 2003). It is furthermore argued that the site is the location of where something transpires, that is, all things that exist or occur do so somewhere, this somewhere is the site. This location is not only the physical location but also the temporal, the phenomena's place in a historical context. It is, furthermore, placed in a teleological location, a location of meaning, that is, where it fits in, in the scope of ends, purposes and tasks. The last location (Schatzki, 2002, p. 43) mentions is the activity-place space, which is “composed of places and paths, where a place is defined as a location to X (where X is an action), and a path is defined as a place […] to get from one location to another.” Eating lunch with a customer while on a business trip is simultaneously taking place in all of these locations, it takes place in a spatio-temporal location, a restaurant during a specific time of the day; moreover, within a teleological structure it takes place within the tasks, purposes and ends of the business travel practices. It is also located in activity-place space, where the restaurant is the location to eat, do business, meet, and so on, but also the path onward in an activity structure; this path could lead to a manifold of different activities such as closing a deal or other meetings. Within this site, doings and sayings, are bundled together into practices and practice-bundles, through understandings, rules, principles, precepts and teleoaffective structures, such as: ends, meanings, emotions, beliefs or projects. Doings and sayings should be understood as actions, which could be both mental and bodily (Schatzki, 1996).

Based on these theoretical concepts, the intent is to capture, explore, and describe the actions, doings, performed by business travellers, at their destination, on a business trip and by that, begin to map out their meal practices. In order to capture practices, Schatzki (2012) mentions that a survey is not a tool to capture the entirety of a practice; however, he does state that it is a means to create a broad overview of a phenomena relating to practice. That is, by conducting a survey study of general patterns of activity within a group, doings can be captured to create the basis for further exploration into the organisation of business travellers’ meal practices.

Method

A web-based questionnaire was developed, by following the step-wise manner suggested by (Boynton and Greenhalgh, 2004), as a means of capturing business travellers’ actions in different meal situations while travelling, as well as while being at home. However, only actions related to being at the destination will be presented in this study.

Initially an interview guide was produced, built around themes associated with the three main meals of Swedish food culture - breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Semi structured interviews (Boynton and Greenhalgh, 2004) were conducted, with the goal to capture actions performed in relation to meals of ten individuals who regularly travelled as a part of their job. The respondents were recruited through a social media platform, aimed at Nordic business travellers, as well as through already established social networks. The respondents were offered the opportunity to choose how they wanted the interview to be conducted, as suggested in the literature (R. Edwards and Holland, 2013; Kvale and Brinkmann, 2014; Rubin and Rubin, 2012). Eight preferred e-mail interviews and two preferred telephone interviews. The data gathered was then used in the construction of the questionnaire, where the actions mentioned by the respondents in the interviews were reformulated as claims (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ). The first draft of the questionnaire was discussed with a reference group of scholars from food and tourism related disciplines, before it was sent on a pilot run to eight business travellers. Input from these eight respondents led to minor changes of the questionnaire, such as the correction of spelling and the clarification of information given. The finished questionnaire comprised two blocks - travelling alone and travelling in the company of someone. This was subsequently divided in to two contexts each - during the travel and while at the destination. Questions, formed as claims, about the meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) were repeated for each context. However, only actions related to being at the destination will be presented in this study. The number of claims varied between nine and eleven. The respondents were asked to rank each claim on a seven-grade rating scale (Oppenheim, 1992), ranging from 1 = do not agree to 7 = completely agree. The final questionnaire was made up of a total of 153 such claims. One claim, regarding the bringing back of lunch to the hotel room while being in company of others, was mixed up in the questionnaire and will not be part of the analysis.

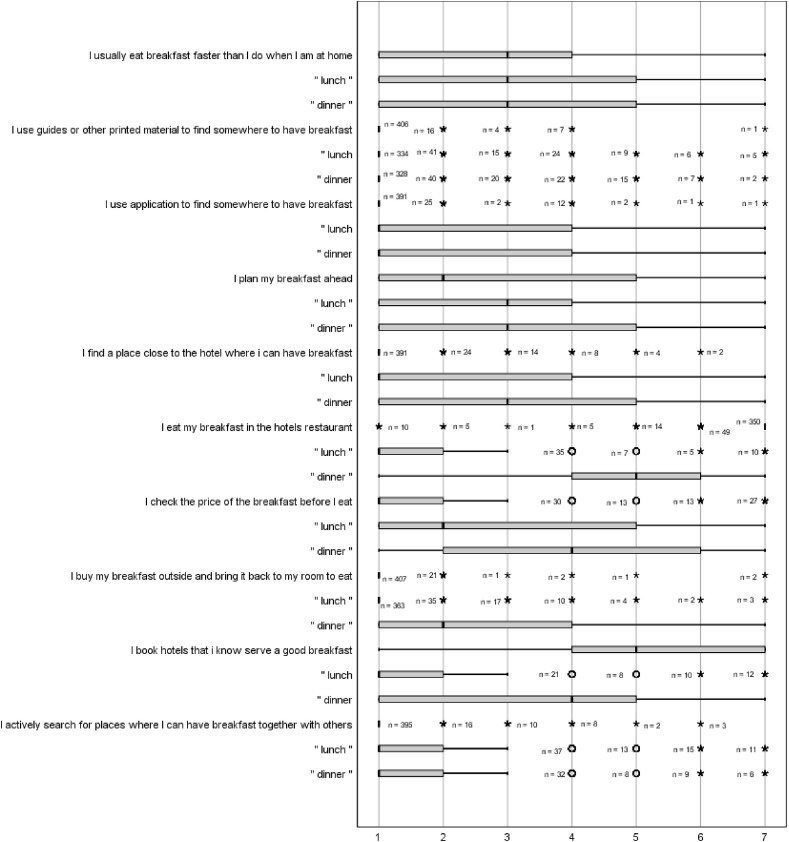

Fig. 1.

Actions at the destination while being alone. The scale is ranging from 1 - “Do not agree” to 7- “Completely agree”. Numbers at outliers denotes number of respondents at each point on the scale. Total n = 434.

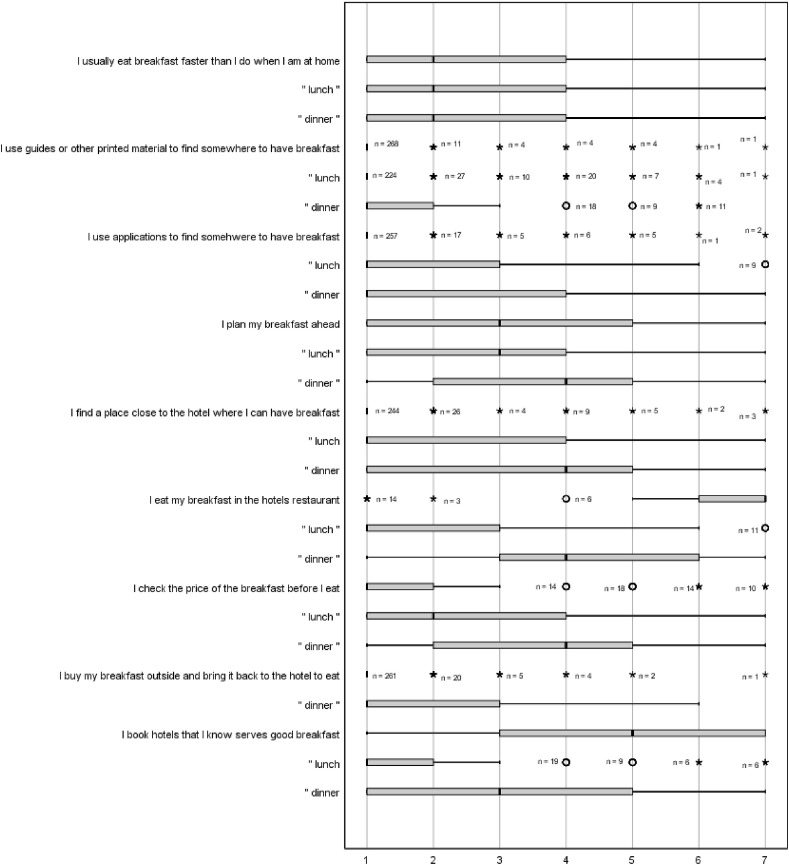

Fig. 2.

Actions at the destination while being in the company of someone else. The scale is ranging from 1 - “Do not agree” to 7 -“Completely agree”. Numbers at outliers denotes number of respondents at the point on the scale. Total n = 293.

Population, administration and analysis

Domestic business travellers, as a group, are an unknown population in the sense that there is no register of who they are. To sample from such a group, a purposive self-recruiting criterion sample approach was deployed. The eligibility criteria were that respondents regularly travelled as a part of their job and with a frequency of at least twice per year. Due to the exploratory character of the study about this unknown population, no calculation of statistical power was made. No ethical permission by the regional ethical board was necessary. No sensitive data as defined by the Swedish law of ethical review was collected and adult business travellers were not deemed to be a vulnerable group. In addition, participation was voluntary, no personal data was asked for and the data was kept confidential.

In April 2018, an invitation to participate in the study and complete the questionnaire was distributed through the newsletter of Scandic Hotel's loyalty program, with an estimated 27000 members - although not all were business travellers. By the closing of the data collection period, after 14 days, the questionnaire URL had been contacted over 2400 times and answered by 538 individuals. No logs of these URL contacts were saved by the service provider so it is not possible to rule out duplicates, however, we deem it improbable that someone would answer the questionnaire more than once.

Data gathered from the questionnaire was analysed for descriptions, and differences in actions related to the meals based on the demographic data collected, both for those travelling alone and in the company of others while being at the destination of their travel. Kruskal-Wallis, Mann-Whitney U, and Fisher's exact test, was used to analyse for variations between the groups in four categories (gender, income, travel days and age). For categories with more than two groups, post hoc analysis was done by Dunn's pairwise test and significance was adjusted for mass significance with the Bonferroni correction. The statistical analysis software IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25.0.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) was used. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reliability & validity

The guidelines to ensure reliability and validity proposed by (Tsang et al., 2017) were guiding the work with the creation of the questionnaire. We sought to establish face validity by conducting interviews with members of the targeted group and, in turn, using their answers as the foundation for discussion with an expert group of scholars, as a first step in the questionnaire creation. The first draft of the questionnaire was distributed to selected number (n = 8) of respondents who were similar to the intended target group. The feedback received motivated some changes to the questionnaire, such as clarifying the information given, correction of spelling, and changing the order of some questions to make the flow more logical. In order to check the internal consistency of the questionnaire, each context of the two blocks was tested by applying Chronbach's alpha with scores ranging from,784 to, 857.

Results

In total, 538 participants answered the questionnaire (Table 1 ). The majority were male (77%), aged between 46-65 (70%), had an income above P75 (56%) and travelled at least 50 days per year (67%). Initially, a general overview of the results will be presented. That is, presenting how the responding business travellers acted in relation to their meals while travelling alone (Fig. 1) and while travelling in the company of someone else (Fig. 2). Following that, analysis made on the basis of demographic variables will be presented (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5 ).

Table 1.

Demographic data and extent of travelling among the participating business travellers (n = 538).

| Gender | Freq | % | Age | Freq | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 125 | 23 | 18–25 | 1 | 0 |

| Male | 413 | 77 | 26–35 | 27 | 5 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 36–45 | 103 | 19 |

| 46–55 | 213 | 40 | |||

| 56–65 | 164 | 31 | |||

| 66+ |

30 |

6 |

|||

| Annual Travel Days | Domestic income percentile; | ||||

| Available from Statistics Sweden | |||||

| Freq |

% |

Freq |

% |

||

| <5 | 2 | 0 | P25 | 2 | 0 |

| 5–24 | 34 | 6 | P25–P50 | 48 | 9 |

| 25–49 | 142 | 26 | P50–P75 | 171 | 32 |

| 50–74 | 158 | 29 | P75–P90 | 265 | 49 |

| 75–100 | 100 | 19 | >P90 | 52 | 10 |

| >100 | 102 | 19 | |||

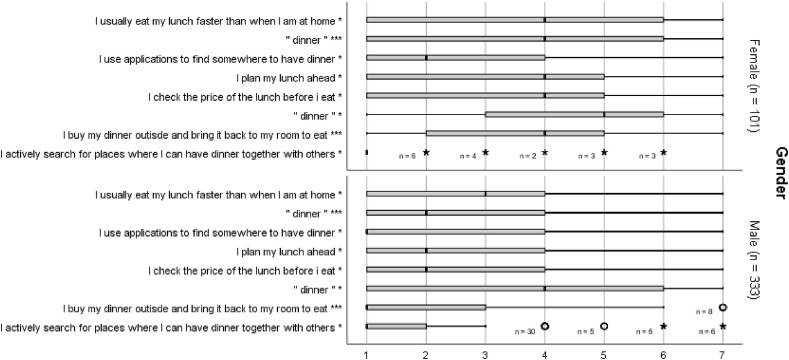

Fig. 3.

Significant differences between females and males while travelling alone analysed by Mann-Whitney U.Notations of p-value * <0,05 *** < 0,001.

Fig. 4.

Significant differences found within the gender category while travelling in the company of someone analysed by Mann-Whitney U.Notations of p-value * <0,05 *** < 0,001.

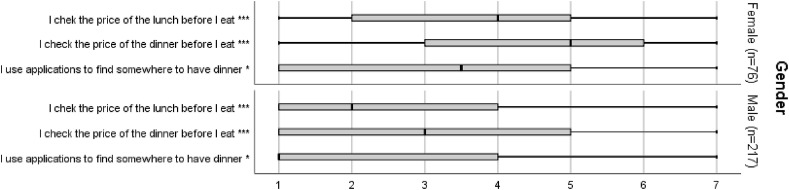

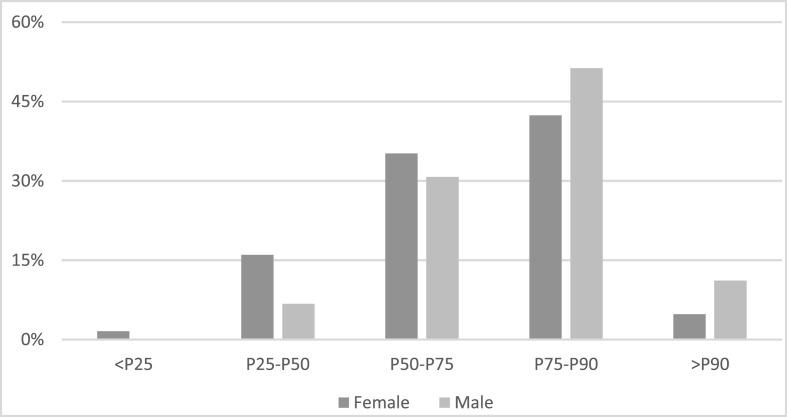

Fig. 5.

Income distribution between female and male respondents as percent of total in each group, sorted into domestic income percentiles (P). There is a statistical difference of income between genders in the group according to Fisher's exact test (p < 0,001).

Meal practices as a whole

The common practice amongst the business travellers in this study was to eat their breakfast at the hotel, and to some extent (2–7 on the ranking scale), eat it faster than when they were at home, whether travelling alone (Fig. 1) or in company with others (Fig. 2). The breakfast was treated as an important aspect of the travel, as it in most cases influenced the booking behaviour of the business traveller, that is, they booked a hotel that they knew served a breakfast they liked and also, to some extent, there was a strategy or plan relating to having breakfast at the destination.

Half of the individuals responded that they, to some extent, used applications for their smartphones to find a restaurant or a food outlet to have lunch, rather than eating lunch at the hotel, which was seldom done. However, in about a quarter of the cases, the lunch was usually had in proximity to the hotel. As with the breakfast, the lunch was reported, to some extent, to have been eaten faster while on a business trip than when having the habitual lunch. The quality of served lunch does not reflect on the booking behaviour as strong as the quality of served breakfast does. In contrast with breakfast though, there was a higher reported price consciousness related to the lunch.

As with the lunch, using smartphones to find a suitable outlet for dinner was an activity performed. However, the most common practice reported was eating dinner at the hotel, even though looking for restaurants close to the hotel was also a common practice, and as with the other meals, the dinner was reported to be eaten faster than the habitual one. Further, the dinner, like the breakfast, seems to have an influence on the booking behaviour. Hotels are to some extent booked based on the image of the dinner served. Dinner was also the meal where the individuals reported the highest amount of price consciousness and a large proportion also reported that they, to some extent, bought food outside of the hotel and brought it back to eat alone in their rooms. Dinner was also the meal that was reported as the most planned ahead meal of the three.

While travelling in the company of someone else, there are a few differences in reported actions (Fig. 2). It seems that, to some extent, the meals are allowed to take a longer time while in the company of someone, rather than when eaten alone. Further, the behaviour of buying dinner outside of the hotel and eating it alone in the room is reported to a lesser extent by travellers in the company of someone, relative to those who travel alone.

Gender

Our data show gender differences in relation to the performance of meal related actions, both while travelling alone (Fig. 3) and while travelling in the company of others (Fig. 4).

Women articulated that they, to a higher degree than men, perceived themselves to consume their lunch (p < 0,05) and dinner (p < 0,001) faster while being away from home for work than they would do while being at home. Furthermore, women were also more dispositioned towards finding somewhere to purchase dinner through the use of some kind of technical assistant, like an application in their phone (p < 0,05). According to our findings, women ranked a higher propensity toward planning their lunches (p < 0,05), and expressed a higher degree of price-consciousness towards the lunch and the dinner (p < 0,05). Women, moreover, showed a higher tendency to buy their food outside of the hotel and bring it back to their room and dine alone (P < 0,001); while men, in contrast, to a larger extent than women (p < 0,05) perceived themselves to actively search for social situations to insert themselves into, to be able to have dinner together with someone, even though they were travelling by themselves.

Travelling together with someone, that is being at the destination of the travel in the company of someone, be it a colleague or a customer, requires another set of performances where the differences between women and men were not as distinct as while the business travellers were travelling alone. However, one aspect that repeats itself, is that the women, to a higher degree than the men, considered themselves to be more price-conscious in relation to the lunch (P < 0,001) and the dinner (P < 0,001), also when being in company with others. They were also using technical devices, such as smartphone applications to find restaurants to eat dinner at, to a higher extent (P < 0,05).

Income

Male respondents had a higher income than the female respondents did (p < 0,001; Fischer exact test) (Fig. 5).

Differences found in the income category (Table 2 ) were in some cases reflected in the same claims present in the gender category, such as the price-consciousness exhibited by the respondents or the use of technical assistance, such as applications from a smartphone, to find a restaurant to eat at.

Table 2.

Variance found in the Income percentile group.

| Domestic income percentile |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P25–P50 | P50–P75 | P75–P90 | >P90 | |

| Claims (Alone) | ||||

| I usually eat my lunch faster when I'm travelling | 4(1–5)a | 2(1–4)b | 2.5(1–4)a,b | |

| I usually eat my dinner faster when I'm travelling | 5(3–6)a,d | 2(1–4)d | 2.5(1–4)a | |

| I use applications to find somewhere to have lunch | 4(1–5)a,b,c | 1(1–4)a | 1(1–3)b | 1(1–2)c |

| I use applications to find somewhere to have dinner | 4(1–6)a | 1(1–4)a | ||

| I control the price of the lunch before I eat | 5(2.5–7)a,d,e | 3(1–5)a | 2(1–4)d | 2(1–3)e |

| I control the price of the dinner before I eat | 6(4.5–7)b,d | 4(2–6)a | 4(2–6)b | 3(1–5)a,d |

| I buy my dinner outside and bring it back to my hotel room | 4(1–5.5)a | 1(1–4)a | ||

| Claims (In company) | ||||

| I buy my dinner outside and bring it back to my hotel room | 2(1–4)a | 1(1–3)b | 1(1–2)b | 1(1–2)a |

| I search for a restaurant close to the hotel where I can have dinner | 5(3–6)b | 3(1–4)a,b | 5(3–6)a | |

Data are presented as mdn(P25–P75), same letter indicate significant difference between groups. a,b,c = p < 0.05; d,e = p < 0.001 analysed by Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's pairwise. All significance values have been adjusted for multiple tests with the Bonferroni correction.

Significant difference related to price-consciousness was found related to both lunch and dinner when the business travellers were travelling alone. The low-income group (P25–P50) experienced a higher degree of price-consciousness that the travellers belonging to the higher income percentiles. Differences in price-consciousness regarding dinner were also observed between the group consisting of travellers in the 50th to 75th percentile group and the travellers from the highest income group (>P90). The utilisation of technical assistance was more common in the lower income group (P25–P50) than in the higher income groups - this was most prominent related to having lunch when being alone. Eating dinner faster was most strongly exhibited in the lower income group (P25–P50). However, in relation to lunch, the mid-income group (P50–P75) experienced that they spent less time on their meals than the higher income groups (>P75). The lower income group were also more prone to buying dinner outside of their hotel and bringing it back to their room than the group of travellers with income between the 75th and 90th percentile - they were also more prone to this performance while being in the company of someone else. While being in the company of others, both the low-income and the high-income groups (P25–P50 & >P90) were more likely than the mid-income group (P50–P75) to search for restaurants outside of the hotel to have their dinner at.

Discussion

The results elucidate parts of business travellers’ actions related to potential meal practices, as a whole, as well as the differences in practices enacted within the gender and income categories.

The results show that in relation to most actions, there is a large variation in how often certain actions are perceived to be taken in relation to the meals. We interpret this as a sign that there are numerous identities and hence multiple practices enacted within the studied context. The behaviour surrounding breakfast described in the results could suggest the existence of a special business traveller identity or practice in the context of Sweden. As a part of strategizing the business trip, as described by Lassen (2010) and Saarenpää (2016), it is possible that hotels are more likely to get booked if they are known to serve a breakfast that the traveller likes. The hotels’ breakfast can function as, what Schatzki (2003) calls a site of practice. It has a place, physical and temporal, it has a place within a teleological structure in relation to the concept of business travel, and it has a place in the activity-place space.

With regards to the lunch meal, at an aggregated level, the data did not show any clear, common, behaviour related to performed non-basic actions, rather the lack of such unified behaviour suggesting a specific practice might be carried on. This could very well be explained by the many different types of business travellers there are, as suggested by Davidson and Cope (2003), and that the practices should not be sought after in relation to the meal but in other, work-related, aspects.

As with the breakfast, the dinner shows signs of being part of a business traveller practice. Gustafson (2012) suggests that the usage of travel time could be used as a means for relaxation – in this study the dinner is conceptualised in the same manner. The restaurant at the hotel is easy to access and offers a time-saving option, as opposed to searching for other establishments to have dinner at. This practice of eating at the restaurant of the hotel is not as distinct while being at the destination in company with others, which might again be explained by the reason for travel. While travelling with others, there might be a higher level of organiser involvement, when the purpose is, for example, a conference. A different set of practices could be at play in those situations.

Difference in the actions taken between women and men emerge when analysing the data based on the reported gender. These differences are, however, more prominent in the context of travelling alone than during the context of travel in the company of someone. While travelling with others to, for example, conferences or organised meetings, Davidson and Cope (2003) suggest that there are different levels of organiser involvement, which might be one explanation for this difference. However, while travelling alone this difference becomes more visible.

The difference was found in relation to two meals, lunch and dinner. Through the lens of social identity theory, these differences could be explained by different identities taking salience, and therefore different social practices are being carried on. Within the context of spending the evening alone at the destination of a business travel, the opportunities to act out different identities, as suggested by Reed (2002), work-related ones are likely more common than when travelling as a group to a trip with organiser involvement. That is, the traveller is not necessarily part of the business traveller group, as a salient collective identity, while being alone and can therefore act in a way more in line with habitual identities.

So, when the men in this study, to some extent, ate their dinner in the hotel's restaurant, or searched for social contexts to insert themselves into to have dinner, perhaps they choose to do this to uphold an image, or keep an identity salient. This could indicate that these practices are more in accordance with the expected practice of male business travel. Whereas the women, albeit they also ate in the restaurant of the hotel, to a larger extent, than the men, did chose to eat alone in their hotel rooms. This may suggest that there are gendered practices linked to business travel.

Significant differences were also found in the income category, with the largest differences being found between the relatively lower (P25–P50) and relatively higher income (P > 75) groups. To be able to make certain aspects of an identity salient, hence acting out its embedded practices, certain prerequisites must be fulfilled. One such prerequisite is the availability of economic capital. The lower income group expressed a higher degree of price consciousness, perhaps related to their usage of technical assistance, while also stating that they more often brought back food to their room than others did. When in the company of someone else, both the lower income and the high-income groups did choose not to eat at the hotel to a larger extent than the income groups in between them. Given the other results of the analysis based on income, it could be stated that there are two different practices being carried out in this context.

The data gathered shows the performances acted, related to non-basic actions, that is, what the business travellers conceive themselves to have done, acting in the world - it does not, however, capture the teleoaffectivity, the meaning, of those actions. Practice theory gives us the hint that there is a teleoaffective structure (Schatzki, 1996; 2002, 2019), or intelligibility, motivating these non-basic actions within the practice of the meal; the questionnaire could however not capture it. This limiting factor of the material on the performance of activities could also be observed when analysis was made on the basis of income level, where we can see differences in performance in meals while travelling in the company of others.

The differences found within the practices carried out by business travellers, opens up for new research to identify the teleoaffectivity and understandings behind the actions carried out in relation to the meals, that is, into the meaning of being a business traveller having a meal while being on a business trip. Furthermore, it opens up for research into what ends and projects motivate the performance of business travellers’ practices.

Conclusions

In this article we have explored actions, as they are perceived to be performed, by domestic business travellers in relation to meals at the destination of a business journey and how these actions vary between social categories, or potential constructors of identity. These actions, or doings, of business travellers are parts of meal practices within the organisation of practices that make up the practice of business travel. What we found in our analysis is that there does not seem to be one, unified, meal practice while travelling for business, but rather a manifold of non-basic actions relating to, what we assume to be, a number of practices relating to the same practice bundle.

The paper has focused on activities related to the facilitation of an eating activity rather than focusing on the food per se. As such, we cannot say how specific dietary preferences, e.g. preferences for plant-based food, organic food, healthy food, has governed the performed activities. We do, however, suggest that this article has opened the door, providing an entry point, into further inquiry of the meals of business travellers.

Furthermore, on the topic of healthy, and health, this article has been written during the global crisis brought forth by CoViD-19. The disease has already proven to be a disaster for the hospitality industry (Gössling et al., forthcoming; Nicola et al., 2020). Consequently, as our results are from the pre-CoViD era, other logics than those observed here might be driving future activities. This is something that future research need to account for.

Managerial implications

This study has elucidated differences in activities and actions related to the meal, between groups, based on gender and on level of income. These differences could possibly be of interest to hospitality and restaurant managers with a customer base made up of business travellers. Knowing, for example, that women are more likely than men to avoid restaurants while travelling alone, opens up for new value offerings related to meals. Furthermore, knowing that economy seems to have an important role, even for a group that is generally perceived as economically well off, also creates opportunity for managers to help their customers to have enjoyable meals.

Funding

This work was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Research and development fund of the Swedish hospitality industry (BFUF). The funding source did not play any role in the design and implementation of the study; collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Author statement

Joachim Sundqvist: Conseptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Visualization, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft Ute Walter: Methodology, Funding acquisition, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision Agneta Hörnell: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Visaualisation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aguilera A. Business travel and mobile workers. Transport. Res. Part A. 2008;42:1109–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Boynton P.M., Greenhalgh T.J.B. Selecting, designing, and developing your questionnaire. 2004;328(7451):1312–1315. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7451.1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B., O'Hara K. Place as a practical concern for mobile workers. Environ. Plann. 2003;35:1565–1587. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R, Cope B. Business Travel: Conferences, Incentive Travel, Exhibitions, Corporate Hospitality and Corporate Travel. Prentice Hall; Harlow, England: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J., Gustafsson I.-B. The five aspect meal model. J. Foodserv. 2008;19:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R., Holland J. Bloomsbury; London: 2013. What is Qualitative Interviewing? [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein J. Columbia University Press; New York: 2014. Fashioning Apetite. [Google Scholar]

- Firat A.F., Shultz C.J. From segmentation to fragmentation: markets and marketing strategy in the postmodern era. Eur. J. Market. 1997;31(3/4):183–207. [Google Scholar]

- Firat A.F., Venkatesh A. Liberatory postmodernism and the reenchantment of consumption. J. Consum. Res. 1995;22(3):239–267. [Google Scholar]

- Fischler C. Food, self and identity. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1988;27(2):275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Fischler C. Commensality , society and culture. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2011;50(3-4):528–548. [Google Scholar]

- Fjellström C. Mealtime and meal patterns from a cultural perspective. Scand. J. Nutr. 2004;48(4):161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tourism, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 1-20. doi:10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708.

- Gronow J., Jääskeläinen A. The dail rhythm of eating. In: Kjaernes U., editor. Eating Patterns: A Day in the Lives of Nordic Peoples. Lysaker , Norge : SIFO - Statens Institutt for Forbruksforskning. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson P. Managing business travel: developments and dilemmas in corporate travel management. Tourism Manag. 2012;33:276–284. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson P. Travel time and working time: what business travellers do when they travel, and why. Time Soc. 2012;21(2):203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson P. Business Travel from the Traveller’s Perspective: Stress, Stimulation and Normalization. Mobilities. 2014;9(1):63–83. doi: 10.1080/17450101.2013.784539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson I.-B., Öström Å., Johansson J., Mossberg L. The Five Aspects Meal Model: a tool for developing meal services in restaurants. J. Foodserv. 2006;17:84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda M., Gharbi A. The postmodern consumer: an identity constructor? Int. J. Market. Stud. 2013;5(2):41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen K.V., Jensen Ø., Gustafsson I.-B. The meal experiences of á la Carte restaurant customers. Scand. J. Hospit. Tourism. 2005;5(2):135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale S., Brinkmann S. 3. rev ed. Studentlitteratur; Lund: 2014. Den Kvalitativa Forskningsintervjun. [Google Scholar]

- Lassen C. Individual rationalities of global business travel. In: Beaverstock J.V., Derudder B., Faulconbridge J., Witlox F., editors. International Business Travel in the Global Economy. Ashgate; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.J., McCool A.C. Business travelers' diet practices. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2008;8(4):3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lund T.B., Gronow J. The daily rhythm of eating. In: Gronow J., Holm L., editors. Everyday Eating in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden: A Comparative Study of Meal Patterns 1997–2012. Bloomsbury Academic; London: 2019. pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mak A.H.N., Lumbers M., Eves A., Chang R.C.Y. Factors influencing tourist food consumption. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2012;31:928–936. [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä J., Kjærnes U., Pipping Ekström M., L, Orange Fürst E., Gronow J., Holm L. Nordic meals: methodological notes on a comparative survey. Appetite. 1999;32:73–79. doi: 10.1006/appe.1998.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola M., Alsafi Z., Sohrabi C., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Iosifidis C.…Agha R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int. J. Surg. 2020;78:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim A.N. New ed. 1992. Questionnaire Design, Interviewing, and Attitude Measurement. (London ; New York) [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D. Identity-based motivation: implications for action-readiness, procedural-readiness, and consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009;19(3):250–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2009.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quan S., Wang N. Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: an illustration from food experiences in tourism. Tourism Manag. 2004;25:297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Reed A. Social identity as a useful perspective for self-concept-based consumer research. Psychol. Market. 2002;19(3):235–266. doi: 10.1002/mar.10011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed A., Forehand M.R., Puntoni S., Warlop L. Identity-based consumer behavior. Int. J. Res. Market. 2012;29(4):310–321. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers H.L., Reilly S.M. A Survey of the Health Experiences of International Business Travelers: Part One—Physiological Aspects. Workplace Health & Safety. 2002;50(10):449–459. doi: 10.1177/216507990205001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin H.J., Rubin I.S. Sage; Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC: 2012. Qualitative Interviewing: the Art of Hearing Data. [Google Scholar]

- Saarenpää K. Stretching the borders: how international business travel affects the work-family balance. Community Work. Fam. 2016;21(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzki T.R. Social Practices: A Wittgensteinian Approach to Human Activity and the Social. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzki T.R. The Pennsylvania State University Press; Pennsylvania: USA: 2002. The Site of the Social. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzki T.R. A New Societist Social Ontology. Philosophy of the Social Sciences. 2003;33(2):174–202. doi: 10.1177/0048393103033002002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schatzki T.R. A Primer on Practices. In: Higgs J, Barnett R, Billett S, Hutchings M, Trede F, editors. Practice-Based Education. Practice, Education, Work and Society. Vol. 6. SensePublishers; Rotterdam: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzki T.R. Social Change in a Material World. Routledge; Oxon: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sundqvist J., Walter U. Deriving value from customer based meal experiences—introducing a postmodern perspective on the value emergence from the experience of the commercial meal. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2017;15(2):171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Sundqvist J, Walter U, Hörnell A. Eat, sleep, fly, repeat: meal patterns among Swedish business travellers. Journal of Gastronomy and Tourism. 2020;4(2):53–66. doi: 10.3727/216929719X15736343324841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H., Turner J. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin W.G., Worchel S., editors. The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Brooks/Cole; Montery, CA: 1979. pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang S., Royse C.F., Terkawi A.S. Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2017;11(5):S80–S89. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_203_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warde A. Polity Press; Cambridge, UK: 2016. The Practice of Eating. [Google Scholar]

- Warde A., Martens L. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2000. Eating Out - Social Differentiation, Consumption and Pleasure. [Google Scholar]

- Warde A., Yates L. Understanding eating events: snacks and meal patterns in Great Britain. Food Cult. Soc. 2017;20(1):15–36. doi: 10.1080/15528014.2016.1243763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. 'We never eat like this at home' - food on holiday. In: Caplan P., editor. Food, Health and Identity. Routledge; Oxon: UK: 1995. pp. 151–171. [Google Scholar]