Abstract

The function and pharmacology of γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors (GABAARs) are of great physiological and clinical importance and have long been thought to be determined by the channel pore–forming subunits. We discovered that Shisa7, a single-passing transmembrane protein, localizes at GABAergic inhibitory synapses and interacts with GABAARs. Shisa7 controls receptor abundance at synapses and speeds up the channel deactivation kinetics. Shisa7 also potently enhances the action of diazepam, a classic benzodiazepine, on GABAARs. Genetic deletion of Shisa7 selectively impairs GABAergic transmission and diminishes the effects of diazepam in mice. Our data indicate that Shisa7 regulates GABAAR trafficking, function, and pharmacology and reveal a previously unknown molecular interaction that modulates benzodiazepine action in the brain.

Gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors (GABAARs) mediate fast inhibitory transmission in the mammalian brain and are ligand-gated pentameric anion channels assembled from various combinations of 19 subunits (1, 2). The abundance and kinetics of GABAARs at synapses fundamentally control inhibitory synapse strength and neural circuit information processing (3–6). Whether native GABAARs contain additional auxiliary subunits that control both trafficking and kinetics of the receptor remains unknown. GABAARs are also the primary targets for a number of drugs, notably benzodiazepines (BDZs), barbiturates, anesthetics, and ethanol (7–10).

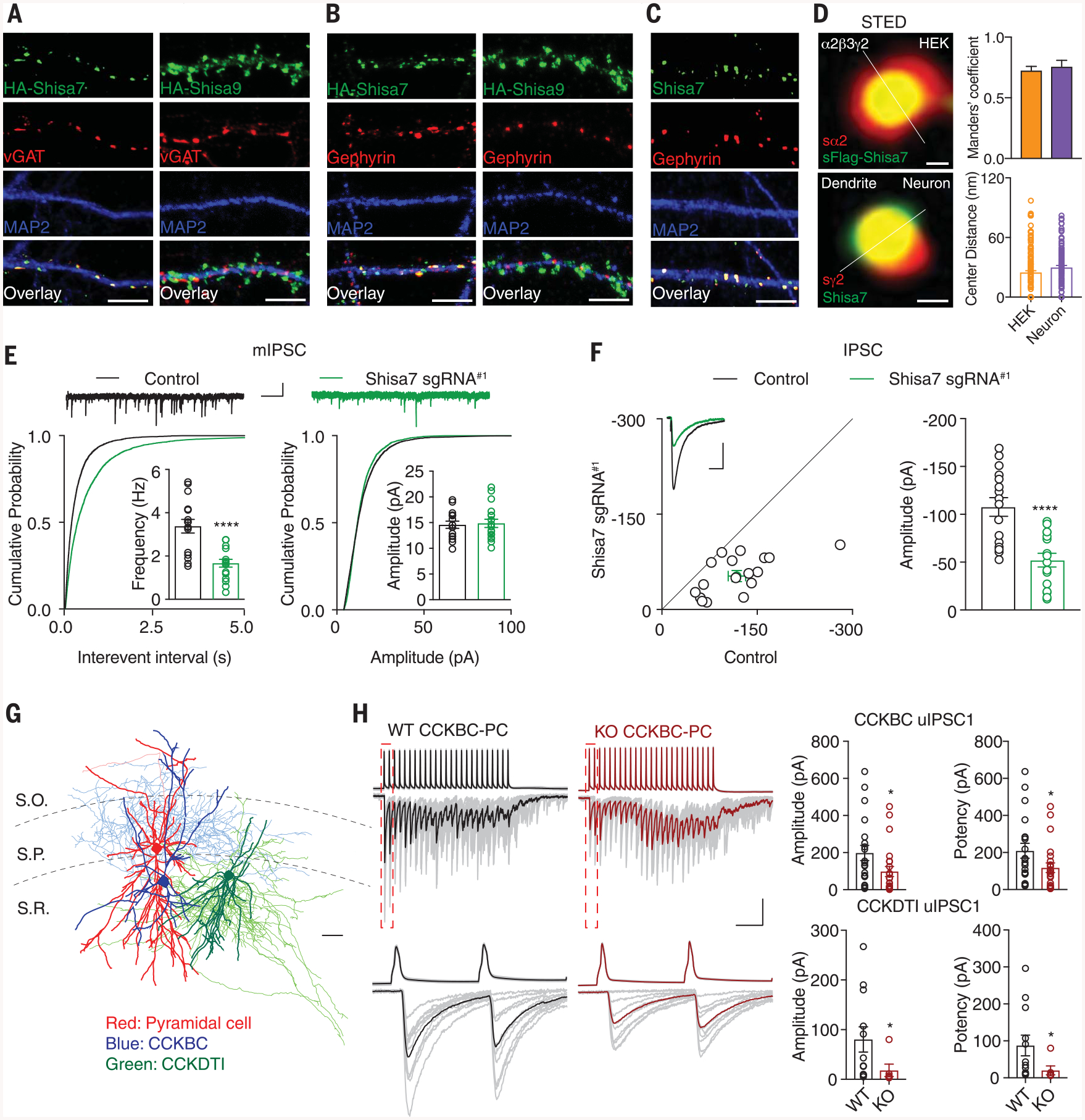

We performed an immunocytochemical assay to examine the subcellular distributions of Shisa family proteins [Shisa6 to −9; also called cystine-knot AMPA receptor–modulating proteins (CKAMPs)] (fig. S1A) in hippocampal neurons, some of which have been implicated in the regulation of glutamatergic transmission (11, 12), and we unexpectedly identified Shisa7 as a membrane protein localized at GABAergic inhibitory synapses. Whereas overexpressed Shisa6 and Shisa9 were localized at glutamatergic synapses (Fig. 1, A and B, and fig. S1, B, D, and E), overexpressed Shisa7 largely colocalized with GABAAR, vesicular GABA transporter (vGAT), or gephyrin puncta (Fig. 1, A and B, and fig. S2, A, B, and E) but not with vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (vGluT1), PSD-95, Homer1, or GluA1 puncta (figs. S1, B and C, and S2, C to F). Recombinant Shisa7 expressed in Shisa7 knockout (KO) neurons colocalized with gephyrin (fig. S2G). Moreover, a monoclonal antibody against Shisa7 confirmed robust colocalization of endogenous Shisa7 with gephyrin (Fig. 1C and fig. S2, H and I). Finally, super-resolution microscopy analysis colocalized Shisa7 with GABAARs in the nanometer range (Fig. 1D and figs. S3, A to C, and S4, A to F).

Fig. 1. Identification of Shisa7 as a critical molecule for inhibitory transmission.

(A and B) HA-Shisa7, but not HA-Shisa9, colocalized with vGAT (A) or gephyrin (B) in hippocampal neurons. Scale bar, 10 mm. (C) Endogenous Shisa7 colocalized with gephyrin in hippocampal neurons. Scale bar, 10 mm. (D) Stimulated emission depletion microscopy (STED) with the line profile analysis showed that Shisa7 and GABAAR subunits colocalized in HEK cells (n = 164 puncta, n = 8 cells) (top) and in neurons (n = 107 puncta, n = 8 neurons) (bottom). The s prefix indicates surface. Scale bar, 60 nm. (E) Single-cell KO of Shisa7 strongly reduced mIPSC frequency but not amplitude in CA1 pyramidal cells (n = 15 for both conditions; t test). Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used for cumulative distributions. Scale bars, 20 pA and 1 s. (F) Dual recording showed that Shisa7 sgRNA#1 strongly reduced IPSCs in CA1 pyramidal cells (n = 16; paired t test). (G) Anatomical reconstructions illustrating a representative CA1 pyramidal cell (red) innervated by a CCKBC (blue) and a CCKDTI (green), used for paired recordings. Scale bar, 100 mm. S.O., stratum oriens; S.P., stratum pyramidale; S.R., stratum radiatum. (H) (Top) Sample averaged traces of CCKBC presynaptic action potentials and corresponding postsynaptic pyramidal neuron uIPSCs evoked by presynaptic stimuli in Shisa7 WT (black) and KO (red) hippocampal slices with individual sweeps shown in gray. Bars: 100 ms/100 pA or 50 mV. (Bottom) Boxed regions of trains (dashed lines in top traces) shown on an expanded time scale. Bar: 12.5 ms. On the right are summary plots of uIPSC amplitudes and potency (CCKBCs: WT n = 20, KO n = 23; CCKDTIs: WT n = 12, KO n = 6; Mann-Whitney U test). Error bars indicate SEM. ****P < 0.0001; *P < 0.05.

The unexpected localization of Shisa7 at GABAergic synapses prompted further investigation into a potential role in regulating inhibitory transmission. We used two different single-guide RNAs (sgRNA#1 and sgRNA#2; see supplementary materials) in this part of our study. sgRNA#1-mediated single-cell genetic deletion of Shisa7 in CA1 pyramidal neurons in acute hippocampal slices produced a strong reduction in frequency, but not amplitude, of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) (Fig. 1E and fig. S5, A to C). Furthermore, dual whole-cell recordings from neighboring transfected and nontransfected CA1 pyramidal neurons revealed significantly reduced evoked IPSCs in neurons expressing sgRNA#1, but not in neurons expressing sgRNA#2 (Fig. 1F and figs. S5, A to C, and S6A). IPSC paired-pulse ratios and excitatory transmission were not altered in neurons expressing sgRNA#1 (fig. S6, B to F). The reduction of IPSCs in neurons expressing sgRNA#1 could be fully rescued by coexpressing the sgRNA#1-resistant Shisa7 (Shisa7*; fig. S6, G to I). In Shisa7 KO mice (fig. S7, A to D), mIPSC frequency, but not amplitude, was strongly decreased in CA1 pyramidal neurons (fig. S7E). Morphologically, interneurons generally segregate into perisomatic and dendrite-targeting subsets (13). To determine if Shisa7 regulates inhibitory inputs on both of these cellular compartments, we examined GABAergic transmission in paired recordings between synaptically coupled stratum radiatum interneurons and CA1 pyramidal neurons, targeting cholecystokinin-expressing basket and dendrite-targeting cells (CCKBCs and CCKDTs, respectively) (Fig. 1G). Shisa7 KO reduced unitary IPSC (uIPSC) amplitudes at both the CCKBC and CCKDTI inputs to CA1 pyramidal neurons (Fig. 1H).

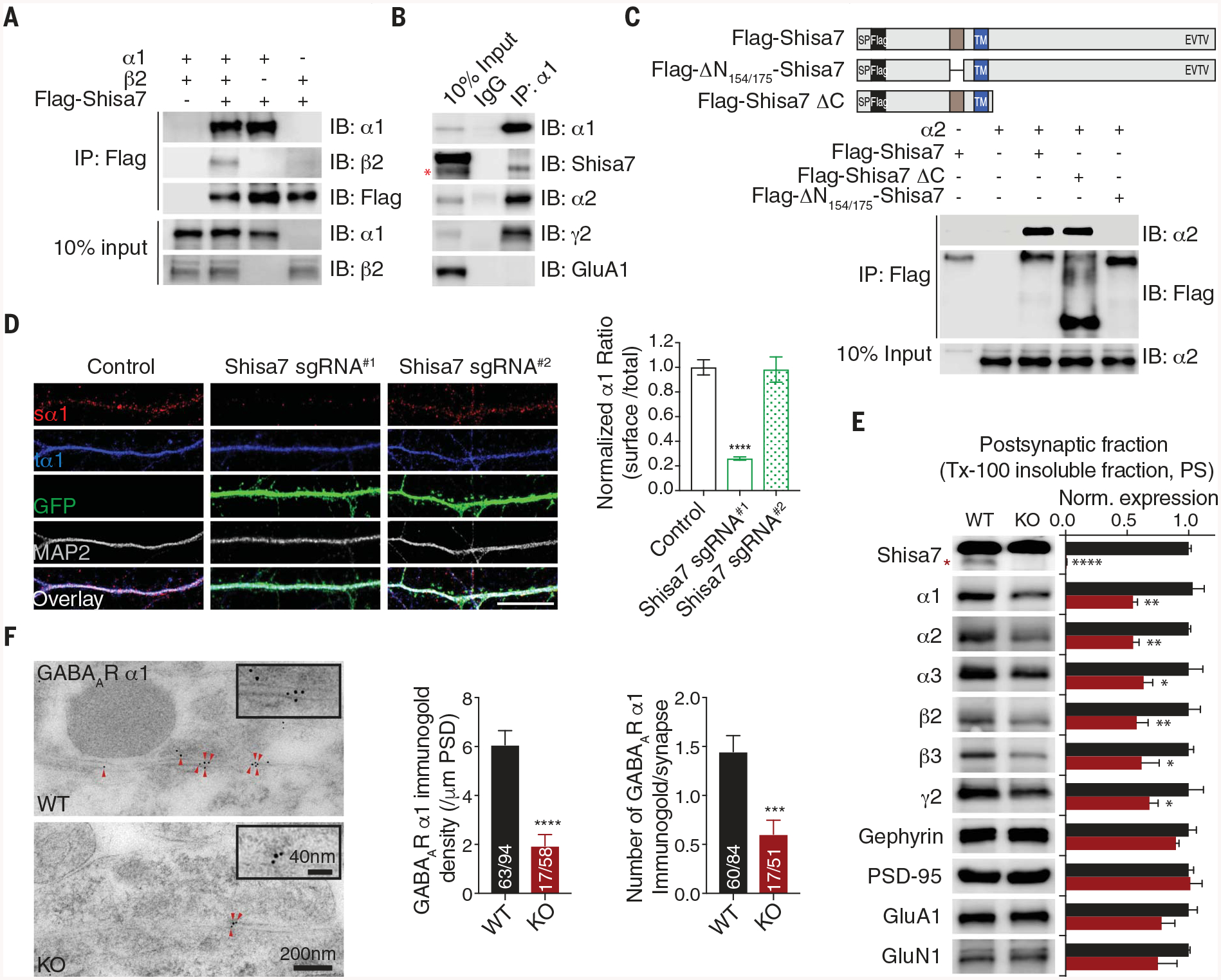

Coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells revealed that α1, α2, and γ2 subunits, but not β2 and β3 subunits, coimmunoprecipitated with Shisa7 (Fig. 2A and fig. S8, A and B). Furthermore, α1 and α2 were detected in Shisa7 immunoprecipitates from detergent-solubilized hippocampal lysates prepared from wild-type (WT) mice but not Shisa7 KO mice (fig. S8C). Similarly, a reverse co-IP confirmed an association between Shisa7 and α1 or α2 subunits in hippocampal lysates (Fig. 2B and fig. S8D), consistent with findings of a recent proteomic study (14).

Fig. 2. Shisa7 binds GABAARs through a distinctive N-terminal domain and controls synaptic abundance of GABAARs.

(A nd B) The α1 subunit coimmunoprecipitated with Shisa7 in HEK cells (A) and in hippocampal lysates (B). IB, immunoblot; IgG, immunoglobulin G. (C) Schematic of Flag-Shisa7, Flag-ΔN154/175-Shisa7, and Flag-Shisa7ΔC. SP, signal peptide; TM, transmembrane domain. In HEK cells, the α2 subunit coimmunoprecipitated with Flag-Shisa7 and Flag-Shisa7ΔC but not Flag-ΔN154/175-Shisa7. (D) Expression of Shisa7 sgRNA#1, but not sgRNA#2, in hippocampal neurons reduced the ratio of surface α1 (sα1) and total α1 (tα1). Control n = 39; sgRNA#1 n = 21; sgRNA#2 n = 18. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. Scale bar, 10 mm. (E) Protein expression in postsynaptic fractions (PS) from Shisa7 WT and KO mice (n = 5 for both conditions; one-way ANOVA was used). Tx-100, Triton X-100. (F) Postembedding immunogold labeling of the α1 subunit in the hippocampal CA1 region showed that Shisa7 KO significantly reduced the density of α1 at the inhibitory postsynaptic density (PSD). Data for α1 density (control n = 63/94, KO n = 17/58) and data for immunogold labeling per synapse (control n = 60/84, KO n = 17/51) were evaluated with a t test. Scale bar, 200 nm (low-magnification images) or 40 nm (high-magnification images). The red asterisk indicates the Shisa7 band. Error bars indicate SEM. ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

We swapped domains of Shisa9, which normally localizes to glutamatergic synapses (fig. S1D) (12), with those of Shisa7 and discovered that the Shisa7 N terminus was critical for its subcellular localization (fig. S9, A to C). Sequence alignment of Shisa6 to −9 revealed a distinctive 22–amino acid domain in the Shisa7 N terminus (fig. S9D). Deletion of this domain (ΔN154–175-Shisa7) largely abolished the colocalization of Shisa7 with gephyrin (fig. S9E). Finally, both Shisa7 and Shisa7-ΔC, which lacks the C terminus, but not ΔN154–175-Shisa7, coimmunoprecipitated with α2 (Fig. 2C), suggesting that this domain (the GABAAR interacting domain, or GRID) is critical for the Shisa7-GABAAR interaction. Finally, cell adhesion assay results supported a direct interaction between Shisa7 and GABAARs (fig. S10).

What are the mechanisms underlying the regulation of GABAergic transmission by Shisa7? In HEK cells, Shisa7 significantly promoted cell surface expression of α2β30γ2 receptors but not α1β2γ2 receptors (fig. S11, A and B). The GRID was critical for Shisa7 to promote GABAAR trafficking to the cell surface (fig. S11C). Similarly, Shisa7 significantly increased GABAAR-mediated whole-cell currents evoked by GABA (10 mM) in cells expressing α2β3γ2 without affecting the GABA median effective concentration (fig. S11, D and E). Although β3 on its own did not associate with Shisa7 (fig. S8A), Shisa7 promoted GABA-evoked whole-cell currents mediated by GABAARs containing β3, no matter which α subunit was present (fig. S11D). Conversely, single-cell genetic deletion or germline KO of Shisa7 significantly reduced surface expression levels of α1, α2, and γ2 GABAAR subunits in hippocampal neurons (Fig. 2D and fig. S12, A to I).

The total expression levels of α2 and α3 were significantly reduced in Shisa7 KO hippocampal lysates (fig. S13A). Moreover, α1, −2, and −3; β2 and −3; and γ2 were significantly decreased in postsynaptic fractions prepared from Shisa7 KO mice (Fig. 2E), indicating reduced synaptic GABAARs in Shisa7 KO neurons. Finally, post-embedding immunogold electron microscopy confirmed that both α1 and α2 were strongly decreased at morphologically identifiable somatic symmetric synapses in hippocampal CA1 region in Shisa7 KO mice (Fig. 2F and fig. S13B).

Analysis of mIPSCs revealed a significantly slower decay in CA1 pyramidal neurons expressing Shisa7 sgRNA#1 and those from Shisa7 KO mice compared with control cells (Fig. 3A and fig. S14A). The decay time constant of CCKBC-mediated uIPSCs was also significantly increased in Shisa7 KO CA1 pyramidal neurons (fig. S14B), suggesting that Shisa7 may speed up GABAAR decay kinetics at synapses. Indeed, at artificial GABAergic synapses formed between hippocampal cultures and HEK cells expressing GABAARs (Fig. 3B), Shisa7 significantly decreased the decay time constant of spontaneous IPSCs (sIPSCs) recorded in cells expressing α1β2γ2 or α2β3γ2 (Fig. 3C and fig. S14D). Notably, sIPSC amplitude was significantly higher in cells expressing α2β3γ2, but not α1β2γ2, with Shisa7 (fig. S14, C and E), consistent with the data presented in fig. S11D. In outside-out patches from HEK cells expressing α1β2γ2 or α2β3γ2, Shisa7 decreased the weighted time constant of deactivation as well as both fast (τfast) and slow (τslow) components of deactivation (Fig. 3D and fig. S14, F and G). However, Shisa7 did not change desensitization of α1β2γ2 (fig. S14H).

Fig. 3. Shisa7 modulates kinetics of GABAergic transmission and GABAARs.

(A) The mIPSC decay time constant was significantly increased in CA1 neurons expressing sgRNA#1 (n = 14 for both conditions; t test). Scale bar, 20 ms, 2 pA. (B) Schematic of coculture of hippocampal neurons with HEK cells. (C) Shisa7 significantly reduced the decay time constant of sIPSCs mediated by α1β2γ2 (n = 13 for both conditions; t test) in HEK cells in coculture. Scale bar, 20 pA, 1 min. (Bottom) Peak-normalized sample traces. Scale bar, 10 ms. GFP, green fluorescent protein. (D) Coexpression with Shisa7 significantly reduced the weighted time constant of deactivation of α1β2γ2 in HEK cells (n = 31 for both conditions; t test). (Left) Peak-normalized sample traces. Scale bar, 50 ms. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

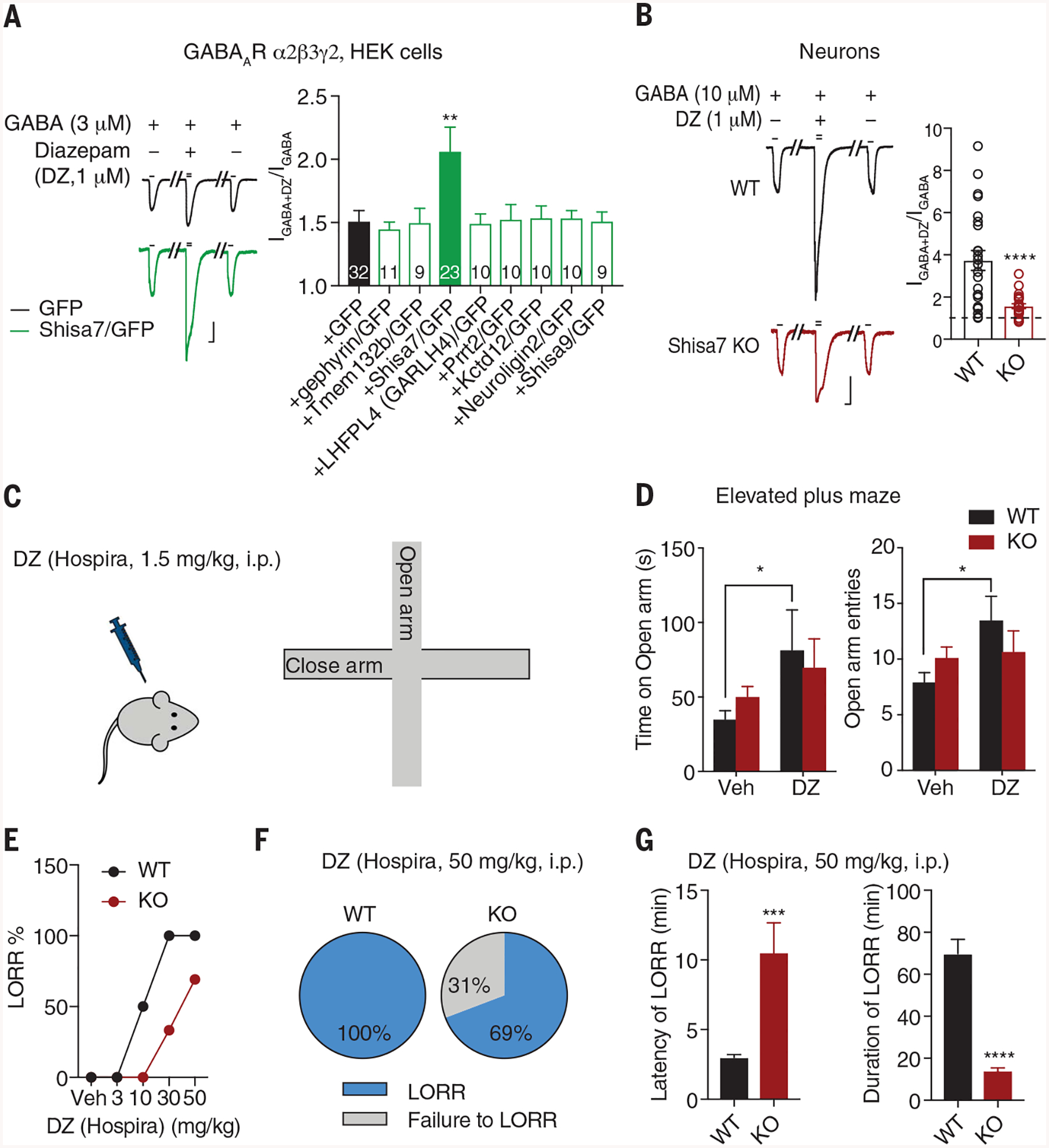

Diazepam (DZ) is a positive allosteric modulator of GABAARs (7–9). In HEK cells, while DZ potentiated nonsaturating GABA-evoked currents of α2β3γ2 receptors, it enhanced currents of α2β3γ2/Shisa7 complexes to a greater degree (Fig. 4A and fig. S15A). None of the other known or putative GABAAR interactors recently identified in GABAAR proteomes (14–20) increased the potentiation of GABA responses (Fig. 4A and fig. S15B). Shisa7 significantly increased the potentiation of GABA responses in cells expressing α1β3γ2, but not cells expressing α1β2γ2 (fig. S16, A to D). Conversely, in Shisa7 KO hippocampal neurons, the potentiating effect of DZ on GABA-evoked currents was strongly diminished (Fig. 4B and fig. S16E). Similarly, DZ-induced enhancement of sIPSCs was greater in WT CA1 neurons than in Shisa7 KO neurons (fig. S16, F and G).

Fig. 4. Shisa7 KO diminishes DZ effects in vitro and in vivo.

(A) Shisa7, but not other molecules, potentiated the DZ effect on GABA response of α2β3γ2 in HEK cells (one-way ANOVA). Scale bar, 200 pA, 2 s. (B) Shisa7 KO significantly reduced DZ-induced potentiation of GABA-evoked whole-cell currents in cultured neurons (WT n = 24; KO n = 23; t test). Scale bar, 500 pA, 2 s. (C and D) DZ (1.5 mg/kg) increased the time spent on open arm and the number of open arm entries in WT mice but not Shisa7 KO mice. Veh, vehicle. (Treatment groups: Veh WT n = 14 and KO n = 21; DZ WT n = 10 and KO n = 15.) Time: treatment [F1,56 = 5.113, P < 0.05]; group [F1,56 = 0.016, P > 0.05]; treatment × group [F1,56 = 0.845, P > 0.05]; entries: treatment [F1,56 = 4.501, P < 0.05]; group [F1,56 = 0.035, P > 0.05]; treatment × group [F1,56 = 3.101, P > 0.05]; two-way ANOVA. (E) Dose-response relationship of DZ in LORR [Veh n = 6 for both conditions; DZ (3 mg/kg) n = 6 for both conditions; DZ (10 mg/kg) WT n = 6 for both conditions; DZ (30 mg/kg) WT n = 7, KO n = 6; DZ (50 mg/kg) WT n = 13 for both conditions). (F) DZ at the hypnotic dose produced LORR in 100% of WT mice (n = 13), but only 69% of KO mice (9 of 13 mice). (G) Shisa7 KO significantly prolonged latency to LORR and shortened duration of LORR after DZ administration (WT n = 13, KO n = 9; t test). Error bars indicate SEM. ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

General behavioral characterizations revealed no obvious differences between WT and Shisa7 KO mice in novel object recognition, social interaction, and marble-burying tests (fig. S17, A and B). However, the action of DZ was severely blunted in Shisa7 KO mice (Fig. 4, C to G). An anxiolytic dose of DZ [1.5 mg per kilogram of body weight (mg/kg), administered intraperitoneally (i.p.)] significantly increased the number of elevated plus maze open arm entries and the time spent in the open arm for WT mice but not for Shisa7 KO mice (Fig. 4, C and D). In addition, DZ strongly reduced motor activity in WT mice but its effect was diminished in Shisa7 KO mice, suggesting a reduced sedative effect of DZ in KO mice (fig. S18A). The ability of DZ to induce the loss-of-righting reflex (LORR) in Shisa7 KO mice also was strongly decreased (Fig. 4E). At the hypnotic dose used (50 mg/kg, i.p.), DZ consistently produced LORR in all WT mice, whereas only ~60 to 70% of Shisa7 KO mice showed the LORR after DZ administration (Fig. 4F and fig. S18B). In the responding population of Shisa7 KO mice, LORR induced by DZ (50 mg/kg, i.p.) was severely compromised, as indicated by substantially increased latency to LORR combined with a markedly shortened duration of LORR (Fig. 4G, fig. S18B, and movies S1 and S2).

We identified Shisa7 as a GABAAR auxiliary subunit—i.e., one that possibly interacts directly with GABAARs, regulates GABAAR trafficking to synapses, and modulates the channel kinetics and pharmacology (see the supplementary text for further discussion). Functionally, Shisa7 plays a crucial role in controlling GABAergic transmission. Genetic inactivation of Shisa7 led to a strong reduction of synaptic GABAARs as well as GABAergic transmission in hippocampal neurons. In addition, Shisa7 shapes inhibitory synaptic responses by speeding up channel decay kinetics. Several membrane molecules (i.e., LHFPL4/GARLH4 and Clptm1) regulate synaptic anchorage and trafficking of GABAARs, although these molecules appear not to modulate GABAAR kinetics (16–19). Our finding that Shisa7 regulates both trafficking and kinetics of the Cl− channel indicates that functional properties of GABAARs are regulated by an auxiliary molecule, in addition to the pore-forming subunits, providing a new dimension for understanding and reanalysis of GABAAR function and pharmacology.

Shisa7 enhances DZ-induced potentiation of both α1- and α2-containing GABAARs in heterologous cells. Correspondingly, disruption of Shisa7-mediated GABAAR regulation in mice significantly reduced DZ actions at cellular and network behavioral levels. Previous studies have demonstrated that distinct GABAAR sub-types mediate sedative or anxiolytic-like effects of BDZs (21–24). This indicates that Shisa7 may influence GABAAR subtype-specific therapeutic effects of BDZs in vivo. Mechanistically, Shisa7 may modulate DZ effects through regulation of BDZ-sensitive GABAAR trafficking to the cell surface and/or increasing DZ efficacy at cell surface GABAARs. Our identification of Shisa7 as an auxiliary subunit of GABAARs capable of modulating DZ actions in vivo highlights a molecular target that can be leveraged for future refinement of psychopharmacological GABAAR therapeutics, an emerging drug discovery strategy that has shown promise in targeting auxiliary subunits of other ion channels (25).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Vicini, D. Bowie, and J. Von Engelhardt for providing some plasmids of GABAAR subunits and Shisa proteins. For help with our experiments, we thank C. Bengtsson and C. Palanzino for neuronal morphological reconstruction, D. Abebe for behavioral tests, V. Schram with Airyscan, and Q. Tian for technical support. We also thank H. Bhambhvani for cloning and characterizing some Shisa7 constructs at the beginning of the project.

Funding: This work was supported by the NIH Intramural Research Program (to W.L., C.J.M., Y.-X.W., R.S.P., L.-G.W., and C.L.) and NHMRC 1058542 and 1120947, Australia (to J.W.L.). The Advanced Imaging Core code is ZIC DC000081.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Data and materials availability: All data are available in the manuscript and supplementary materials.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

science.sciencemag.org/content/366/6462/246/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S18

References (26–62)

Movies S1 and S2

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Sigel E, Steinmann ME, J. Biol. Chem 287, 40224–40231 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen RW, Sieghart W, Pharmacol. Rev 60, 243–260 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacob TC, Moss SJ, Jurd R, Nat. Rev. Neurosci 9, 331–343 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luscher B, Fuchs T, Kilpatrick CL, Neuron 70, 385–409 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vithlani M, Terunuma M, Moss SJ, Physiol. Rev 91, 1009–1022 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrant M, Nusser Z, Nat. Rev. Neurosci 6, 215–229 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen RW, Adv. Pharmacol 73, 167–202 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sieghart W, Adv. Pharmacol 72, 53–96 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sieghart W, Savić MM, Pharmacol. Rev 70, 836–878 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engin E, Benham RS, Rudolph U, Trends Pharmacol. Sci 39, 710–732 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klaassen RV et al. , Nat. Commun 7, 10682(2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Engelhardt J et al. , Science 327, 1518–1522 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelkey KA et al. , Physiol. Rev 97, 1619–1747 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura Y et al. , J. Biol. Chem 291, 12394–12407 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heller EA et al. , PLOS ONE 7, e39572(2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamasaki T, Hoyos-Ramirez E, Martenson JS, Morimoto-Tomita M, Tomita S, Neuron 93, 1138–1152.e6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davenport EC et al. , Cell Reports 21, 70–83 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu M et al. , Cell Reports 23, 1691–1705 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ge Y et al. , Neuron 97, 596–610.e8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tyagarajan SK, Fritschy JM, Nat. Rev. Neurosci 15, 141–156 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudolph U et al. , Nature 401, 796–800 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKernan RM et al. , Nat. Neurosci 3, 587–592 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Löw K et al. , Science 290, 131–134 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crestani F, Martin JR, Möhler H, Rudolph U, Nat. Neurosci 3, 1059(2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maher MP, Matta JA, Gu S, Seierstad M, Bredt DS, Neuron 96, 989–1001 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.