INTRODUCTION

Telemedicine, defined as “the application of information and communication technologies for providing healthcare services at a distance without the need for direct contact with the patient,” was initially conceived as an opportunity for practices to reach more patients (1). Since the COVID-19 (Coronavirus disease 2019) pandemic, telemedicine has become a lifeline to practices seeking to maintain patient access to care and financial viability (2). Quite simply, telemedicine is “crossing the chasm” between being an interesting but rarely used technology to being essential (3,4). Physicians have at least the following 2 important questions: Should I keep telemedicine long term in my practice? What issues should I consider?

We outline important considerations on telemedicine, including licensing requirements, malpractice coverage, choice of platform, and reimbursement. This study not only serves to provide a roadmap for sustainable integration of telemedicine into gastroenterology (GI) practices and other specialties but also provides information on more acute issues surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic.

TELEMEDICINE IN CHRONIC DISEASE MANAGEMENT

Traditional healthcare is expensive for patients in several following ways that we rarely consider: transportation to-and-from visits, childcare expenses, lost time from work, and others (5). Telemedicine is especially useful to patients with chronic gastrointestinal conditions who typically require frequent visits. A recent randomized clinical trial enrolling patients with inflammatory bowel disease over a period of 1 year found that active patient monitoring over nurse-led telemedicine resulted in noninferior care and fewer hospitalizations, compared with standard in-person care alone (6). In hepatology, the Specialty Access Network‐Extension of Community Healthcare Outcome program administered by the Veterans Health Administration suggested improved mortality among patients with liver disease by linking primary care providers directly with specialists remotely, compared with standard in-person care alone (7).

Learning the language of telemedicine and identifying the “key people in the room.”

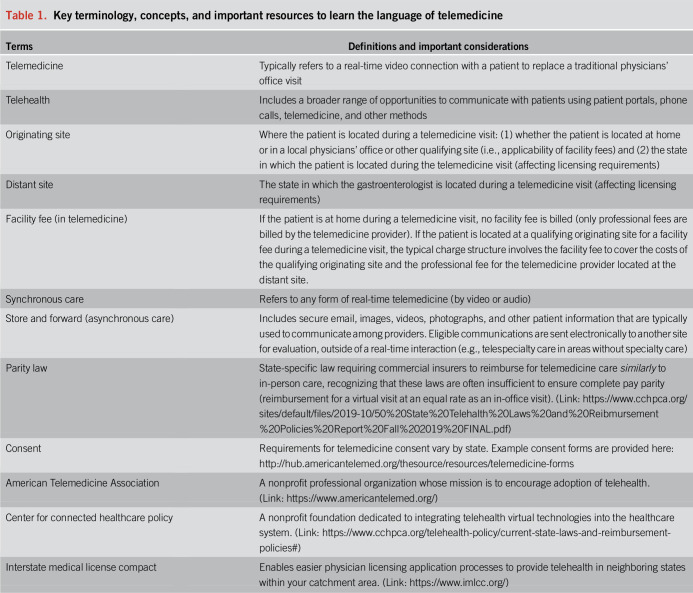

We outline important terminologies for physicians and other providers to understand the language of telemedicine and identify several key resources and stakeholders to help physicians stay up to date (Table 1). Frequently encountered terminologies include originating vs distant site, synchronous vs asynchronous care, and parity laws.

Table 1.

Key terminology, concepts, and important resources to learn the language of telemedicine

PERCEIVED BARRIERS TO USE

Does my medical license allow me to provide telemedicine?

In most states, the full professional medical license usually covers the ability to perform telemedicine visits with patients residing in your state. However, physicians may need to obtain a license in a neighboring state to see patients who are physically located in a neighboring state (see the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact [link: https://www.imlcc.org/] for expedited licensing). Many states now participate in interstate licensing for telemedicine, allowing expedited applications for licensure (8).

Does my malpractice coverage include telemedicine?

Malpractice coverage varies among insurance carriers; some carriers include this coverage, but others may need for you to add a rider or premium.

Will I be reimbursed?

The easiest way to work through your practice's reimbursement strategy is to break down your payer mix into the following 3 broad groups: Medicare, Medicaid, and commercially insured. Specific to traditional Medicare, coverage historically did not include the patient's home as an originating site and restricted telemedicine only to patients in a designated rural area, with the origin of telemedicine services at a clinic, hospital, or certain other type of medical facility (9). During the COVID-19 pandemic, Medicare dropped the originating site requirement enabling patients to receive care from home. Medicare advantage plans have traditionally offered more telemedicine reimbursement options than traditional Medicare, and some have no originating site requirement (10).

It is important to recognize that Medicaid plans are federally funded but state administered; thus, coverage varies by state. Fortunately, an increasing number of states are dropping originating site requirements.

For commercial insurance, there is significant heterogeneity in coverage, both between and within states. State-specific parity laws ensure commercial insurance coverage for telemedicine services; however, providers should directly contact private payers to assess for restrictions and payment rates.

How common are technology problems for patients?

Availability of appropriate internet services and technological competence play a key role on the patient side. Especially in rural areas, internet access and speed may be a limiting factor. Similarly, some persons lack technological competence and are not able to use virtual communication platforms. Patients should be asked about such limitations before initiating a virtual encounter and to see whether there are any correctable actions that can be taken.

Is telemedicine appropriate for every patient?

Although COVID19 with its constraints forces us to defer face-to-face visits, virtual encounters have their limitations. As providers start offering telemedicine, they should consider the most appropriate target group(s) for such mediated encounters, start with them, and expand, as they gain experience and confidence.

Are there any special health information privacy concerns?

Privacy concerns matter, even if we are temporarily allowed to use less secure lines. Providers should be in closed rooms and should ask patients to use a location that does not allow others to overhear the conversation.

HOW DO I BILL AND CODE?

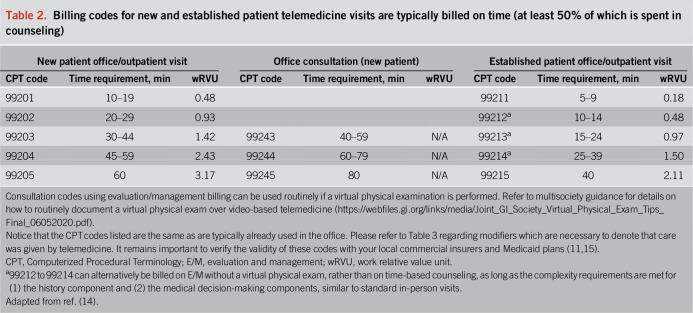

Although obvious, a physical examination is not required to bill successfully for telemedicine visits. However, you still need to meet the appropriate time-based (counseling) or evaluation- and management-based (complexity) requirements for billing as you already do in the office (11). It is also important to check local payer-specific requirements that may deny reimbursement for initial consults (new patient visits) using telemedicine. For example, before the COVID pandemic, traditional Medicare did not reimburse for new patient visits provided by telemedicine. Table 2 outlines the applicable Computerized Procedural Terminology billing codes for your standard telemedicine new and established patient visits across Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial insurers (Table 3 for review of commonly used modifiers; pay attention to your individual payer requirements).

Table 2.

Billing codes for new and established patient telemedicine visits are typically billed on time (at least 50% of which is spent in counseling)

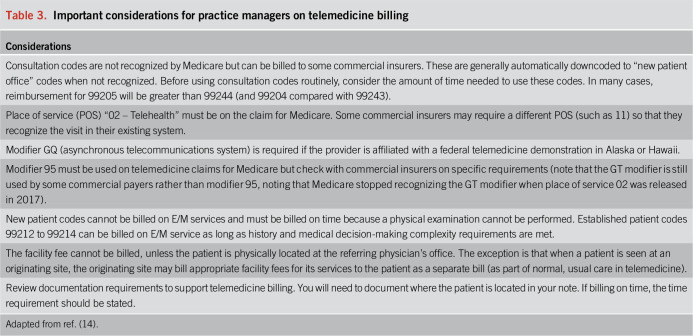

Table 3.

Important considerations for practice managers on telemedicine billing

Several other reimbursement mechanisms exist for ancillary telemedicine services you might consider, although coverage varies significantly among insurers. These mechanisms include G2012 and G2010 (virtual check-ins), 99421 to 99423 (e-visits), and 99358/99358 (prolonged non–face-to-face care). Table 3 adds important details for your practice manager to consider in designing your reimbursement strategy. The American College of Physicians provides a living document of telemedicine coding during the COVID pandemic (Link: https://www.acponline.org/practice-resources/covid-19-practice-management-resources/telehealth-coding-and-billing-during-covid-19).

CHOOSING A TELEMEDICINE PLATFORM

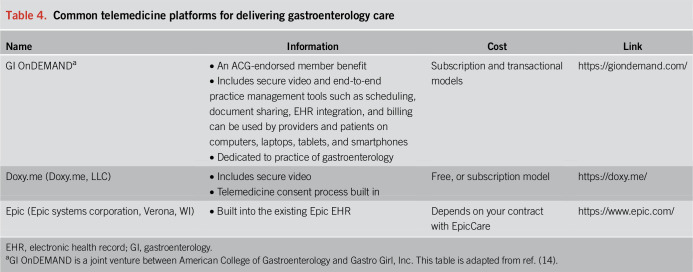

A variety of options are available for telemedicine services: see Table 4 for modalities that have been used by leaders of the ACG (American College of Gastroenterology) Practice Management Committee. Some electronic health record systems have embedded telemedicine platforms allowing for direct patient videoconferencing. Specific platforms devoted to telemedicine are also available. For example, Doxy.me is a telemedicine platform that provides services that span different provider types. Such platforms may allow providers in smaller practices access to telemedicine services they may not otherwise have had outside of tertiary care settings.

Table 4.

Common telemedicine platforms for delivering gastroenterology care

Recently, some platforms have evolved into a “virtual care model,” in which audiovisual communication between patients and providers is supplemented with a variety of other services. For example, a platform specific to GI providers supported by the American College of Gastroenterology (GI OnDEMAND) complements telemedicine services with disease specific educational materials and an online support community. There may be opportunities to integrate nutritional, psychological, and other services that may not always be available in traditional outpatient practice settings.

Whichever modality is chosen, the potential to depart from a set in-office schedule can allow providers more autonomy and flexibility regarding when they provide patient care. This can be potentially helpful to mitigate provider “burnout” (12).

Know and test your technology. Compared with phone calls, the visual connection may add to the value of an encounter by keeping communication partners engaged and by integrating nonverbal cues. In this context, providers should keep in mind that the ‘face value’ of the visual link may require facing the camera rather than the monitor.

CHANGES IN TELEMEDICINE POLICIES DURING COVID-19

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and an increasing number of state governors and medical boards reduced the burden on multistate licensing requirements for out-of-state providers and increased reimbursement and recognition for telemedicine services across insurance carriers. The Office for Civil Rights and the Department of Health and Human Services has stated that it will “not impose penalties for noncompliance with the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act Rules in connection with the good faith provision of telemedicine using such nonpublic facing audio or video communication products during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency” (13). Many of these reductions are tied to the ongoing state of emergency and may be temporary; thus, practices should start to “think long term” as they plan for continued telemedicine post-COVID.

CONCLUSIONS

We provided a roadmap for gastroenterologists and other specialists to understand the language of telemedicine. We also outlined particular considerations toward implementing telemedicine in practice. The ACG Practice Management Toolbox (link: http://webfiles.gi.org/docs/Toolbox/Essential_Guide_to_Telemedicine_in_Clinical_Practice.pdf) is a useful resource containing additional considerations including consent, practice policies, and scheduling processes in this rapidly expanding area of clinical care (14).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Guarantor of this article: Eric D. Shah, MD, MBA.

Specific author contributions: All authors were involved in study concept and design. E.D.S. authored the initial draft of the manuscript, and all authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final copy.

Financial support: E.D.S. is supported by the AGA Research Foundation's 2019 American Gastroenterological Association-Shire Research Scholar Award in Functional GI and Motility Disorders.

Potential competing interests: J.J.K. is the chief medical officer of Gastro Girl and Director of Clinical Operations of GI OnDEMAND. GI OnDEMAND is a joint venture between the American College of Gastroenterology and Gastro Girl. S.T.A. is a consultant for GI OnDEMAND. E.D.S. has no disclosures.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the members of the 2020 American College of Gastroenterology Practice Management Committee who assisted with editing of the ACG Practice Management Toolbox (“American College of Gastroenterology Practice Management Toolbox: Essential Guide to Telemedicine in Clinical Practice: EASY STEPS TO RAPID DEPLOYMENT”) that supports this article (Committee Chair: Dr. Louis Wilson, MD, FACG, Wichita Falls Gastroenterology Associates, Wichita Falls, Texas).

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel CA. Transforming gastroenterology care with telemedicine. Gastroenterology 2017;152:958–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1679–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. Telemedicine 2020 and the next decade. Lancet 2020;395:859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah ED, Rothstein RI. Crossing the chasm: Tools to define the value of innovative endoscopic technologies to encourage adoption in clinical practice. Gastrointest Endosc 2020;91:1183–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah ED, Siegel CA. Systems-based strategies to consider treatment costs in clinical practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:1010–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cross RK, Langenberg P, Regueiro M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of TELEmedicine for patients with inflammatory bowel disease (TELE-IBD). Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:472–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su GL, Glass L, Tapper EB, et al. Virtual consultations through the Veterans administration SCAN-ECHO project improves survival for Veterans with liver disease: Virtual consultations through the Veterans administration. Hepatology 2018;68:2317–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wicklund E. Telemedicine Licensure Compact Is Now Live in Half the Country. mHealth Intelligence. xtelligent Healthcare Media; (https://mhealthintelligence.com/news/telemedicine-licensure-compact-is-now-live-in-half-the-country) (2019). Accessed April 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.MLN booklet. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid services (https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/TelehealthSrvcsfctsht.pdf). Accessed April 30, 2020.

- 10.Wilcock AD, Rose S, Busch AB, et al. Association between broadband internet availability and telemedicine use. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lunt S. Navigating telehealth billing requirements. MGMA (https://www.mgma.com/resources/financial-management/navigating-telehealth-billing-requirements). Accessed April 30, 2020.

- 12.Sorenson G. 3 Ways Telemedicine Reduces Provider Burnout. Physician's Weekly. (https://www.physiciansweekly.com/3-ways-telemedicine-reduces-provider-burnout/) (2018). Accessed April 30, 2020.

- 13.Notification of Enforcement Discretion for Telehealth Remote Communications during the COVID-19 Nationwide Public Health Emergency. Federal Register. 85 FR 22024-22025 (45 CFR 160, 45 CFR 164). 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah E, Amann S, Karlitz J. American College of Gastroenterology Practice Management Toolbox: Essential Guide to telemedicine in clinical practice: Easy steps to rapid deployment. (http://webfiles.gi.org/docs/Toolbox/Essential_Guide_to_Telemedicine_in_Clinical_Practice.pdf). Accessed April 28, 2020.

- 15.Centers for Medicare, Medicaid Services. Physician Fee Schedule Search (https://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/search/search-criteria.aspx). Accessed April 30, 2020.