Abstract

Objective

To determine the efficacy of dapsone as a glucocorticoid-sparing agent in maintenance-phase pemphigus vulgaris (PV).

Design

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with a crossover arm for those who failed treatment.

Setting

A US multicenter outpatient study.

Patients

A total of 19 subjects enrolled among 5 centers, 9 randomized to receive dapsone and 10 to receive placebo. Inclusion criteria were biopsy and direct immunofluorescence-proven PV controlled with glucocorticoids and/or cytotoxic agents, disease in maintenance phase, and aged 18 to 80 years. Physicians had tried at least 2 tapers of glucocorticoids unsuccessfully and had 30 days of stable steroid dosage. Treatment for any patient unable to taper glucocorticoids by more than 25% within 4 months was declared a failure, and the patient was allowed to switch to the opposite medication while maintaining the double-blind.

Main Outcome Measure

The ability of patients to taper to 7.5 mg/d or less within 1 year of reaching the maximum dosage of the study drug.

Results

Of the 9 patients receiving dapsone, 5 were successfully treated, 3 failed treatment, and 1 dropped out of the study. Of the 10 patients receiving placebo, 3 were successfully treated, and 7 failed treatment. This primary end point favored the dapsone-treated group but was not statistically significant (P=.37). Four patients who failed treatment while receiving placebo were switched to treatment with dapsone. Of these, 3 were successfully treated after switching to dapsone treatment, and 1 failed treatment. We found that, overall, 8 of 11 patients (73%) receiving dapsone vs 3 of 10 (30%) receiving placebo reached the primary outcome of a prednisone dosage of 7.5 mg/d or less.

Conclusion

This trial demonstrates a trend to efficacy of dapsone as a steroid-sparing drug in maintenance-phase PV.

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV), an autoimmune vesiculobullous disorder that primarily affects adults, has a high mortality rate prior to glucocorticoid (GC) therapy, and with GC treatment has high morbidity. Disease activity waxes and wanes, with mean remission rates of 23% with GC treatment and 29% with GC and adjuvant treatment.1 Immunosuppressants, such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclophosphamide, are frequently used as GC-sparing agents, although to our knowledge only 1 controlled study using an oral adjuvant has been performed.2-11

The clinical course and therapy of PV have 3 therapeutic phases.1 High dosages of GC treatment achieve initial control of the acute disease during phase 1 (control). Phase 2 (consolidation) is characterized by constant medication type and dosage until most lesions are healed and itching ceases. Then, in phase 3 (maintenance), the dosage of GCs is gradually tapered. Often, patients with PV have a protracted maintenance phase, which leads to a substantial cumulative GC dosage and considerable morbidity, with complications such as osteoporosis, adrenal suppression, and predisposition to infection, cataracts, and diabetes mellitus.12 Attempts to taper the prednisone dosage often lead to flares of the disease in these patients.

Dapsone as an adjuvant treatment for PV was first reported by Winkelmann and Roth in 196013 and since then has been shown to be effective in controlling the disease in single cases or small series.1,14-20 Prior to the initiation of this placebo-controlled trial, we treated 9 consecutive patients with PV with dapsone and used our experience to design this study.21 To our knowledge, this trial is the first randomized placebo-controlled study (RCT) in the United States of patients with PV, and there have been just 2 other RCTs reported in the literature.22,23 The objective of this study was to substantiate the previous findings on the use of dapsone in PV and establish the efficacy of dapsone in comparison with a placebo-treated control group. The study was designed to determine if dapsone facilitated tapering of GCs in steroid-dependent patients with otherwise controlled disease.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

This multicenter RCT randomized patients to receive dapsone, 50 mg/d, or placebo, in addition to the maintenance dosage of GC; the study had a crossover arm for treatment failures. The complete blood cell count and alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels were checked after the first week by an independent monitor to maintain study blinding. If the laboratory parameters were within reference range, the dosage was increased in 25-mg increments each week, with repeated blood tests after each increment. Dapsone administration was increased to 150 mg/d if the dosage was tolerated. A maximum of 200 mg/d was given to those patients who did not respond to 150 mg/d only if the hemoglobin level remained higher than 9 g/dL and did not drop more than 2 g/dL. (To convert hemoglobin to grams per liter, multiply by 10.0.) When the maximum dosage of study medication was reached, the complete blood cell count and alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels, as well as the pregnancy test if applicable, were checked monthly.

Repeated attempts were made to taper steroids after the study treatment had begun, using a standardized protocol that involved weekly decreases in steroid dosage. Patients whose steroid dosage was more than 40 mg/d were tapered by 10 mg/wk, or less if warranted by the activity of the disease. Below a steroid dosage of 40 mg/d or 60 mg every other day, a detailed taper protocol was suggested, in which the patients received a specific steroid dosage for 1 to 3 weeks. The 2 tapering schedules used for the trial and for initial attempted tapers were based on center-specific variation related to use of prednisone daily vs every other day (Table 1). Because clinical experience is that patients with PV in protracted phase 3 exhibit a therapeutic minimum GC dosage, regardless of the tapering schedule used, the end point of change in GC dosage from baseline was not likely to be effected by the tapering schedule.

Table 1.

Glucocorticoid Taper Schedules

|

Prednisone Dosage, mg/d × 7 d | ||

| 40 | 17.5 | 5 |

| 35 | 15 | 4 |

| 30 | 12.5 | 3 |

| 25 | 10 | 2 |

| 20 | 7.5 | 1 |

|

Prednisone, mg Every Other Day × 8 da | ||

| 40-35 | 40-5 | 12.5-1 |

| 40-30 | 40-4 | 12.5-0 |

| 40-25 | 40-3 | 10-0 |

| 40-20 | 35-3 | 7.5-0 |

| 40-18 | 30-3 | 6-0 |

| 40-15 | 30-2 | 5-0 |

| 40-15 | 25-2 | 4-0 |

| 40-13 | 20-2 | 3-0 |

| 40-10 | 17.5-2 | 2-0 |

| 40-7.5 | 17.5-1 | 1-0 |

| 40-6 | 15-1 | 0 |

This refers to the taper schedule for patients on every other day below 40 mg/d. Thus, “40-35” means 40 mg one day 35 mg the next day, 40 mg the next day, and so forth, for a total of 8 days on the 1 dosing regimen.

Flares were treated according to their severity as defined and characterized by the principal investigator at each site for the individual patient. Disease activity was established according to a standardized index. Disease extent was quantitated as mild (<20 blisters and/or <1 palm size in area [using the investigator's palm as a rough gauge of area]); moderate (20-40 blisters and/or 2 palm sizes in area); or severe (>40 blisters and/or >2 palm sizes in area). Disease extent in the mucosa was quantitated as mild (1-5 small lesions), moderate (6-10 lesions), or severe (>10 lesions or extensive erosions). In cases of minor flares, the dosage prior to tapering steroids was resumed. For moderate flares, the dosage was increased by 20 mg/d. For severe flares, an increase of 40 mg/d or 60 mg every other day was recommend. After a flare, the tapering was resumed as soon as the disease was stabilized (ie, no new lesions and evidence of healing of established blisters). Patients were interviewed about adverse events or complications of their disease, treatment compliance, and any changes in adjunctive therapy.

Patients who were unable to taper their steroids by more than 25% within 4 months were switched to the other arm of the study while maintaining blinding. The only time a patient could be switched was after the initial 4-month trial. Patients who dropped out of the study were followed up for 2 more months. The only restriction on concomitant medication for the patients entered into the study was rifampicin, which lowers serum dapsone levels.

PARTICIPATING CENTERS

The following US centers participated: Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan; New York University, New York; Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago, Illinois; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas. The trial was conducted with full approval by the institutional review boards at the respective sites and conformed to the current version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

SUBJECTS

Inclusion Criteria

Patients were required to have an established history of PV with a diagnosis based on histologic findings and direct immunofluorescence. Patients had to have chronic disease in maintenance phase, controlled with steroids and/or stable dosages, for at least 2 months, of cytotoxic agents, including azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or methotrexate. Dosages of cytotoxic agents were not stopped during the trial to introduce just 1 new variable, the new study drug. Patients must have been unable to taper steroids at least twice prior to inclusion, and the steroid dosage must not have been tapered more than 10% within the last 30 days. The steroid dosage at inclusion in the study had to be in the range of 15 to 40 mg/d or 20 to 60 mg every other day. Patients had to be 18 to 80 years of age and provide informed consent.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients were excluded from the study if they were able to taper steroids without recurrence of the disease or if they had early, severe disease that did not respond to high dosages of prednisolone, cytotoxic agents, plasmapheresis, or other modalities. Patients could not be included in the study if they were pregnant or breastfeeding, had ischemic heart disease, a hemoglobin level of less than 10 g/dL, or quantitatively insufficient levels of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Patients were also excluded if they had a history of allergy to dapsone or had other contraindications to the use of the drug. Patients with a history of medication noncompliance were not included in the study. The patients were not to have received pulsed steroids, pulsed cyclophosphamide, or plasmapheresis within the last 2 months prior to enrollment.

CRITERIA FOR TREATMENT DISCONTINUATION

Participation in the study was discontinued if the patient's hemoglobin dropped below 9 g/dL; leukocyte level, below 1.9 × 103/mm3; albumin, below 0.75 of the lower limit of the reference range; bilirubin (total), increased more than 4.9 times the upper limit of the reference range; serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase, increased more than 5.0 times the upper limit of the reference range; or alkaline phosphatase, increased 2.0 times the upper limit of the reference range; or if the patients had diarrhea with liquid stools or signs of dehydration, nausea, and vomiting more than 3 times a day; had clinical signs of dehydration; or if 3+ proteinuria or 2+ red blood cells in the urine were observed. Treatment was also to be discontinued if the patients developed peripheral neuropathy or psychosis. Patients who missed taking more than 20% of their treatment dosage or who did not return for scheduled appointments were dropped from the study.

RANDOMIZATION AND BLINDING

Eligible patients were assigned to either of the 2 treatment groups according to a computer-generated stratified randomization schedule with a block size of 4 (generated by Jacobus Pharmaceuticals, Princeton, New Jersey, who provided the dapsone and placebo). The study medication was packaged and labeled according to a medication code schedule generated before the trial, and the patients were allocated sequentially at each center. They received either the study drug or placebo in bottles labeled with a patient number and a bottle number. Each drug bottle had a 2-part tear-off label. Study medication identification was concealed and could be revealed only in case of emergency. The 3-digit bottle number prior to blinded crossover began with 0. After crossover, the patients received bottles that had a number starting with 4. The dapsone and placebo were color and taste matched. Because treatment with dapsone leads frequently to a clinically insignificant drop in hemoglobin level, clinical monitors observed the laboratory values for the duration of the study to uphold the blinding of the treating physicians. Treatment assignments, including those switched because of lack of response on the first arm of the study, were not revealed to study patients, investigators, clinical staff, or study monitors until all patients had completed therapy and the database had been finalized.

OUTCOMES

The primary efficacy measure was the percentage of patients whose steroid dosage had been tapered down to at least 7.5 mg/d within 1 year of reaching the maximum dosage of the study drug. Treatment of patients who maintained a dosage of less than 7.5 mg/d for more than 30 days was defined a success. Patients had to have received the study drug for at least 50 days for their treatment to be defined a failure in the event of early termination of the study or early crossover owing to failure of 1 arm of the protocol. Patients were considered to have failed treatment if their steroid dosage could not be reduced by more than 25% within 4 months after completing the upward titration of the study drug. Safety was assessed by reports of adverse events, clinical examination, and clinical laboratory tests.

DISEASE MONITORING

Patients were assessed monthly for 1 year after the highest dapsone dosage was reached. Monthly visits included assessment of disease activity, compliance, medication dosage and adjustment, adverse events, and laboratory tests, and these findings were recorded on case report forms.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Based on a series of 5 patients, a sample size of 24 patients per treatment group was calculated to give a 95% power to detect a difference in remission of 80% for the dapsone group and 20% for the placebo group at the 1% 2-sided significance level using the χ2 test. Primary analysis was to be on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis; the analysis presented herein is based on the first planned intermediate effectiveness analysis during the trial. The Fisher exact test was used, with no corrections for multiple looks at the data. In view of the small eventual sample size and the poor rate of completion of treatments in both the dapsone and placebo arms, it was decided to perform an exploratory per-protocol analysis. Analysis of the baseline characteristics was performed with Fisher exact and t test as appropriate.

RESULTS

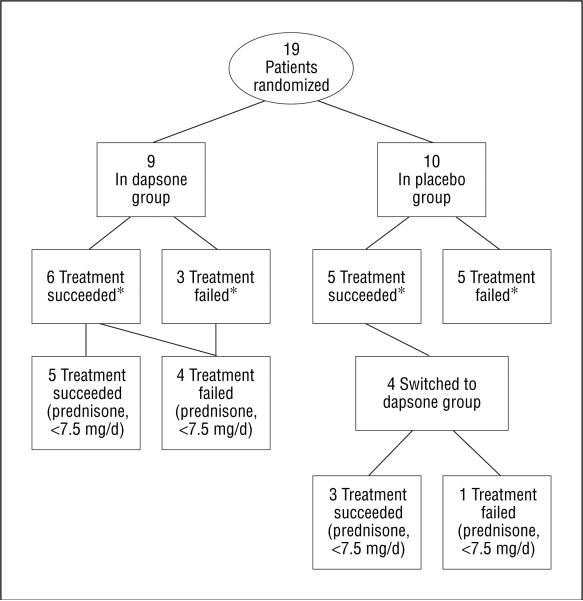

A total of 19 patients were successfully recruited in 5 US academic centers from June 1997 to January 2003 (Table 2). Nine patients (47.4%) were randomized to the dapsone group and 10 patients (52.6%) to the placebo group. After failure with the first treatment arm, 4 patients were switched to the dapsone group. One patient in the dapsone group (Table 2, patient 3) never returned to follow-up appointments after randomization and discontinued all treatment at that point. It is unclear whether she ever took any study medication and according to the protocol was considered a dropout. She was included in the ITT analysis. The flowchart (Figure 1) indicates how many patients met success by being able to reduce their dosage to 7.5 mg/d or less of prednisone. Including those who switched groups, the mean (SD) time of follow-up once the 7.5 mg/d dosage was obtained for placebo “successes” was 137(80) days (median, 91 days), whereas for dapsone successes it was 122(42) days (median, 119 days). Patients 2, 4, 6, 7, and 10 had their dosage tapered by the every-other-day GC protocol. The baseline comparison (Table 3) demonstrated no statistically significant differences between the groups (see Table 3 for P values).

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics

| Patient Characteristic | Outcome | First Arm | Second Arm | Comment | Sex/Age, y | Duration of Disease, mo | Location of Lesions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | Success with placebo | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | June 3, 1997, 40 mg | Completed study | M/31 | 40 | Skin | ||

| May 13 1998, >6.5 mg | |||||||

| October 8, 1998, 0 mg | |||||||

| End date, dosage | January 27, 1999, 0 mg | ||||||

| Patient 2a | Failure with placebo (first arm) and success with dapsone (second arm) | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | November 24, 1997, 40 mg every other day | July 15, 1998, 40 mg every other day | Switched to dapsone group after failure at 233 d; followed 261 d in dapsone arm | F/40 | NA | Oral | |

| End date, dosage | July 15, 1998, 40 mg every other day | February 25, 1999, 15 mg every other day | |||||

| April 1, 1999, 0 mg | |||||||

| Patient 3 | Dropped out of dapsone group | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | December 23, 1997, 20 mg | Dropped out; discontinued all treatment after drug dispensation; never showed up again; not part of per-protocol analysis | F/53 | 10 | Oral | ||

| End date, dosage | January 19, 1998, 20 mg | ||||||

| Patient 4 a | Failure with placebo | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | January 20, 1998, 60 mg every other day | Followed 62 d and dropped out after flare | F/42 | 23 | Oral | ||

| End date, dosage | March 4, 1998, 60 mg every other day | ||||||

| Patient 5 | Failure with dapsone | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | February 13, 1998, 17.5 mg | Dapsone was never advanced beyond 50 mg; patient noncompliant; not part of per-protocol analysis | M/53 | 20 | Oral and skin | ||

| End date, dosage | September15, 1998, 15 mg | ||||||

| Patient 6 a | Success with placebo | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | February 23, 1998, 20 mg | Met definition of success at 224 d, then flared 91 d after met definition of success and was followed 294 more d | M/45 | 28 | Oral | ||

| July 27, 1998, 6 mg | |||||||

| July 28, 1998, 0 mg | |||||||

| End date, dosage | September 1, 1998, 3 mg | ||||||

| Patient 7 a | Failure with placebo | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | April 28, 1998, 40 mg every other day | Flared at d 70 and did not want to continue | F/57 | >180 | Oral and skin | ||

| End date, dosage | July 21, 1998, 40-20 mgb | ||||||

| Patient 8 | Failure with placebo (first arm) and dapsone (second arm) | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | September 10, 1998, 30 mg | December 3, 1998, 25 mg | Followed 84 d on placebo, then switched to dapsone group; noncompliant after 89 d receiving dapsone but unable to taper steroids; followed 187 d after crossover | M/44 | 7 | Oral and skin | |

| End date, dosage | December 3, 1998, 25 mg | June 18, 1999, 15 mg | |||||

| Patient 9 | Failure with placebo | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | October 15, 1998, 35 mg | Followed 162 d and unable to taper; flared and stopped study | M/45 | 8 | Oral and skin | ||

| End date, dosage | April 2, 1999, 60 mg | ||||||

| Patient 10 a | Success with dapsone | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | March 12, 1999, 20 mg | Completed study at 378 d | M/51 | 25 | Skin | ||

| May 21, 1999, 7.5 mg | |||||||

| June 4, 1999, 0 mg | |||||||

| End date, dosage | March 24, 2000, 0 mg | ||||||

| Patient 11 | Success with dapsone | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | April 22, 1999, 30 mg | Finished 267 d | F/37 | 24 | Oral | ||

| January 17, 2000, 7.5 mg | |||||||

| End date, dosage | June 14, 2000, 6 mg | ||||||

| Patient 12 | Success with dapsone | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | April 23, 1999, 15 mg | AE hypersensitivity; finished 109 d and tapered steroid prior to AE | M/19 | 25 | Skin | ||

| End date, dosage | October 8, 1999, 5 mg | ||||||

| Patient 13 | Success with placebo | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | November 19, 1999, 35 mg | Finished 252 d | M/64 | 5 | Oral | ||

| June 5, 2000, 7 mg | |||||||

| End date, dosage | July 28, 2000, 5 mg | ||||||

| Patient 14 | Failure with dapsone | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | January 25, 2000, 30 mg | Failed after 143 d and not switched to dapsone group | M/39 | 39 | Oral | ||

| End date, dosage | June 16, 2000, 30 mg | ||||||

| Patient 15 | Failure placebo (first arm) and success dapsone (second arm) | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | May 23, 2000, 20 mg | February 12, 2001, 120 mg | Flared within 30 d after reaching prednisone dosage <7.5 mg/d judged a failure, and switched to dapsone group with increase to 120 mg prednisone; followed 180 d while receiving dapsone | M/60 | NA | Skin | |

| End date, dosage | January 9, 2001, 5 mg | June 11, 2001, 7.5 mg | |||||

| July 9, 2001, 3.5 mg | |||||||

| Patient 16 | Success with dapsone | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | September 10, 2001, 60 mg | Patient had met the criteria of success; completed 301 d with taper of steroids, then flared | F/38 | 11 | Oral | ||

| End date, dosage | August 21, 2002, 3 mg | Discontinued after hospital admission with pneumonia (unrelated to dapsone treatment); dosage was never increased to >125 mg dapsone | |||||

| Patient 17 | Failure with dapsone | M/43 | NA | Oral and skin | |||

| Begin date, dosage | January 4, 2002, 17 mg | ||||||

| End date, dosage | February 23, 2002, 15 mg | ||||||

| Patient 18 | Failure with placebo (first arm) and success with dapsone (second arm) | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | October 1, 2002, 20 mg | February 11, 2003, 25 mg | Failed treatment with placebo after 126 d with inability to taper and flare; followed 293 d after switching groups | F/55 | 27 | Oral | |

| End date, dosage | February 11, 2003, 25 mg | December 2, 2003, 6 mg | |||||

| December 15, 2003, 5 mg | |||||||

| January 9, 2004, end of study | |||||||

| Patient 19 | Success with dapsone | ||||||

| Begin date, dosage | January 10, 2003, 20 mg | Completed study | F/34 | 3 | Skin | ||

| July 31, 2003, 7.5 mg | |||||||

| September 25, 2003, 0 mg | |||||||

| End date, dosage | March 11, 2004, 0 mg |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; NA, not available.

Glucocorticoid tapering occurred with an every-other-day schedule.

Refers to 40 mg alternating with 20 mg every other day.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients in the study. An asterisk indicates success based on ability to decrease steroid dosages by 25% from baseline.

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristicsa

| Variable | Dapsone (n=9) | Placebo (n=10) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starting steroid dosage, mean, median (range), mg | 25.5, 20 (15-30) | 29, 35 (20-40) | .51 |

| Taper schedule (patients, No.) | |||

| Daily (8) | Daily (6) | .30 | |

| Every other day (1) | Every other day (4) | ||

| Immunosuppressive drugs | |||

| Azathioprine (3) | Azathioprine (7) | ||

| Mycophenolate mofetil (1) | Mycophenolate mofetil (1) | ||

| Gold (1) | |||

| Sex, No, (%) | |||

| Female | 4 (44) | 4 (40) | .61 |

| Male | 5 (56) | 6 (60) | |

| Duration of disease, mean, median (range), mo | 19.6, 22.5 (3-39) | 40.0, 25 (5-180) | .35 |

| Oral/skin | 2 Oral and skin | 3 Oral and skin | .52 |

| 3 Skin | 5 Oral | ||

| 4 Oral | 2 Skin |

An intention-to-treat analysis.

ITT ANALYSIS

Outcomes of the study are presented according to the primary ITT analysis. Five of the 9 patients in the dapsone group (55.6%) were able to reduce their steroid dosage to less than 7.5 mg/d compared with 3 of the 10 patients in the placebo group (30%) (Table 4). This difference was not statistically significant (P=.37). The trial also defined treatment failure in terms of the inability to reduce the steroid dosage by more than 25% within 4 months after completing the upward titration of the study drug. Six of the 9 patients in the dapsone group were able to reduce the steroid dosage by 25%, whereas 5 of 10 patients in the placebo group were able to do so. This difference was not statistically significant (P=.65). Figure 1 details the success of being able to taper prednisone to 7.5 mg/d or less. Patients who were unable to reduce their prednisone dosage by 25% after 4 months of the highest dosage of study drug could be switched to the other arm. The investigators were given the option of switching the patients to the other arm of the protocol, but it was not mandatory. Crossover was blinded, so that investigators who felt that patients may have experienced some improvement while receiving the study drug would be less likely to want to switch the patient to the other arm of the protocol. Graphs in Figure 2 detail steroid dosages for patients in the dapsone and placebo arms, including those switched to the other group.

Table 4.

Success and Failure of Dapsone vs Placebo in Reducing Steroid Dosage to 7.5 mg/d or Lessa

| No. (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| First Treatment | Dapsone | Placebo | Total |

| Success | 5 (55.6) | 3 (30.0) | 7 (36.8) |

| Failure | 4 (44.4) | 7 (70.0) | 12 (63.2) |

| Total | 9 (100) | 10 (100) | 19 (100) |

An intention-to-treat analysis.

Figure 2.

Dosages of prednisone. A, For all patients treated with dapsone; B, for all patients treated with placebo. An asterisk indicates the patients switched to the dapsone treatment group. The numbers in the key represent number of patients.

ADVERSE EVENTS

Treatment with dapsone leads regularly to hemolysis and methemoglobinemia. Because hemolysis is an expected adverse effect of the dapsone, patients with a hemoglobin level of less than 10 g/dL were not eligible for participation, and participation in the trial was to be discontinued for a drop of hemoglobin to less than 9 g/dL. The blood cell counts of all patients were monitored by independent observers. One patient developed mild dyspnea secondary to methemoglobinemia that did not require stopping treatment. One patient developed paresthesias that may have been potentially related to dapsone, necessitating a dosage reduction of dapsone. One patient developed an exanthem with desquamation on his trunk and extremities. Findings from a skin biopsy demonstrated an interface dermatitis. The skin changes were associated with an increase in liver function tests (aspartate aminotransferase level as high as 303 U/L, alanine aminotransferase level as high as 482 U/L, and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase level as high as 574 U/L) with negative test results for hepatitis B and C, as well as an eosinophilia level of 13.3%. (To convert aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase to microkatals per liter, multiply by 0.0167.) These abnormalities were believed to be secondary to treatment with azathioprine, which was discontinued with subsequent resolution of the rash. Dapsone was continued until the end of the observation period. One serious adverse event was recorded; a patient was hospitalized for a pneumonia, which was judged to be independent of the dapsone treatment.

COMMENT

These exploratory results are based on intermediate analysis, which is limited by insufficient recruitment. Although this study did not demonstrate statistically significant superiority of dapsone over placebo in its primary ITT analysis (P =.37), careful clinical analysis of the data can support and substantiate the evidence that previously had only been gained from case series.

Depending on the method of analysis, the response rate to dapsone in our study ranged from 44.4% (strict ITT), to 71.4% (per protocol, no crossover) to 72.7% (per-protocol analysis including the patients who switched groups). This response rate had been the anticipated response rate derived from case series. Given the treatment alternatives for maintenance-phase PV, this suggests that dapsone may be a suitable treatment alternative. In 2 of the 4 initial failures of dapsone treatment, 1 patient experienced a flare while receiving dapsone, which was never increased to more than 50 mg/d, and a second was hospitalized for an unrelated pneumonia 1 month after the dapsone dosage was increased to 125 mg/d and discontinued participation in the study. One of the patients in the placebo group whose treatment failed was treated for only 2 months, whereas the others received prolonged courses of study medication.

All 3 patients who responded to placebo during the trial were also treated with azathioprine. By carefully tapering the dosage of steroids over 5 months, 8 months, and 11 months, respectively, these patients could be weaned off high dosages of steroids. Whether this reduction reflects the azathioprine effect or natural remission of the disease cannot be established. The remission rate thus observed in this highly selected population of patients with PV was higher than had been initially anticipated.

As far as those whose treatment with placebo failed are concerned, it is noteworthy that the disease of 3 of the patients actively flared during the study and they needed substantially increased dosages of prednisone. One of these patients was switched to the dapsone group and within 4 months was able to taper the steroid dosage to less than 7.5 mg/d and was thus considered a treatment success in the dapsone group.

Substantial administrative support for this type of complex autoimmune disease trial is essential. Simplification of the study design and selection criteria is often not an option because stricter selection criteria would make recruitment even more difficult or make the study patients not comparable (eg, they would not all be in the maintenance phase of the disease).

Although a comparison to other steroid-sparing treatments of PV is not possible based on an RCT, the treatment of PV with dapsone is less expensive than immunomodulatory treatments that are often administered. The response rate approached 80% in patients who actually received the study drug for an appropriate time, which means that this inexpensive and relatively nontoxic drug is an appropriate adjunctive therapy for patients whose disease is in the maintenance phase but who are dependent on steroids to control it.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH K24-AR 02207).

Role of the Sponsor: The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Previous Presentation: This work was presented at the Society of Investigative Dermatology; May 6, 2005; St Louis, Missouri; and is published in abstract form in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology (2005;125:1088).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Werth had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study conception and design: Werth, Fivenson, Pandya, Rico, and Jacobus. Acquisition of data: Werth, Fivenson, Pandya, and Chen. Analysis and interpretation of data: Werth, Fivenson, Albrecht, and Jacobus. Drafting of the manuscript: Werth and Albrecht. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Werth, Fivenson, Pandya, Chen, Rico, Albrecht, and Jacobus. Statistical analysis: Albrecht and Werth. Obtaining funding: Werth. Administrative, technical, and material support: Werth, Fivenson, Pandya, Rico, Albrecht, and Jacobus. Study supervision: Werth.

Additional Contributions: Jacobus Pharmaceuticals kindly provided the study drug. Kathy Ales, MD, made thoughtful suggestions on the manuscript. Karen R. Houpt, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, contributed her assistance as the blinded observer, reviewing laboratory findings and adjusting dapsone dosages.

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00429533

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bystryn JC. Adjuvant therapy of pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120(7):941–951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enk AH, Knop J, Enk A, Knop J. Mycophenolate is effective in the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135(1):54–56. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powell AM, Albert S, Al Fares S, et al. An evaluation of the usefulness of mycophenolate mofetil in pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(1):138–145. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mimouni D, Anhalt GJ, Cummins DL, Kouba DJ, Thorne JE, Nousari HC. Treatment of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus with mycophenolate mofetil. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(6):739–742. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.6.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fellner MJ, Katz JM, McCabe JB. Successful use of cyclophosphamide and prednisone for initial treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114(6):889–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piamphongsant T. Treatment of pemphigus with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide. J Dermatol. 1979;6(6):359–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1979.tb01927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chrysomallis F, Ioannides D, Teknetzis A, Panagiotidou D, Minas A. Treatment of oral pemphigus vulgaris. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33(11):803–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1994.tb01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benoit Corven C, Carvalho P, Prost C, et al. Treatment of pemphigus vulgaris by azathioprine and low doses of prednisone (Lever scheme). Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130(1, pt 1):13–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aberer W, Wolff-Schreiner EC, Stingl G, Wolff K. Azathioprine in the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(3, pt 1):527–533. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akhtar SJ, Hasan MU. Treatment of pemphigus: a local experience. J Pak Med Assoc. 1998;48(10):300–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mimouni D, Nousari CH, Cummins DL, Kouba DJ, David M, Anhalt GJ. Differences and similarities among expert opinions on the diagnosis and treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(6):1059–1062. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)02738-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeHoratius DM, Sperber BR, Werth VP. Glucocorticoids in the treatment of bullous diseases. Dermatol Ther. 2002;15(4):298–310. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winkelmann RK, Roth HL. Dermatitis herpetiformis with acantholysis or pemphigus with response to sulfonamides. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82(3):385–390. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1960.01580030079010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haim S, Friedman-Birnbaum R. Dapsone in the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. Dermatologica. 1978;156(2):120–123. doi: 10.1159/000250907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jablonska S, Chorzelski T. When and how to use sulfones in bullous diseases. Int J Dermatol. 1981;20(2):103–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1981.tb00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piamphongsant T. Pemphigus controlled by dapsone. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94(6):681–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb05168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barranco VP. Dapsone: other indications. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21(9):513–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1982.tb01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seah PP, Fry L, Cairns RJ, Feiwel M. Pemphigus controlled by sulphapyridine. Br J Dermatol. 1973;89(1):77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1973.tb01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearson RW, O'Donoghue M, Kaplan SJ. Pemphigus vegetans: its relationship to eosinophilic spongiosis and favorable response to dapsone. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116(1):65–68. doi: 10.1001/archderm.116.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piamphongsant T, Ophaswongse S. Treatment of pemphigus. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30(2):139–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb04229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heaphy MR, Albrecht J, Werth VP. Dapsone as a glucocorticoid-sparing agent in maintenance-phase pemphigus vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(6):699–702. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.6.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mentink LF, Mackenzie MW, Toth GG, et al. Randomized controlled trial of adjuvant oral dexamethasone pulse therapy in pemphigus vulgaris: PEMPULS trial. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(5):570–576. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.5.570. [published correction for error in dosage appears in Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(8):1014]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beissert S, Werfel T, Frieling U, et al. A comparison of oral methylprednisolone plus azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil for the treatment of pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(11):1447–1454. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.11.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]