Abstract

Introduction

Traditionally, laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication (LNF) has been considered an inpatient procedure. Advances in surgical and anesthetic techniques have led to a shift towards outpatient LNF procedures. However, differences in surgical outcomes between outpatient and inpatient LNF are poorly understood. The objectives of this study were (1) to describe the frequency of outpatient LNF in a national cohort and (2) to identify any differences in complications or readmission rates between outpatient and inpatient LNF.

Methods

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database was used to identify elective LNF cases from 2012 to 2016. Patients discharged on the day of surgery were compared to those discharged 24–48 h post-operatively. Outcomes included 30-day readmission and death or serious morbidity (DSM). Bivariate analyses were completed with Chi squared testing for categorical variables and two sided t tests for continuous variables. Associations between outpatient surgery and outcomes were assessed using multivariable logistic regression. Differences in readmission were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier failure estimates and log-rank tests.

Results

Of 7734 patients who underwent elective LNF, 568 (7.3%) were discharged on the day of surgery. The overall 30-day readmission rate was 4.1% (n = 316) and the overall rate of DSM was 1.0% (n = 79). The most common 30-day readmission diagnoses overall were infectious complications (16.1%), dysphagia (12.9%), and abdominal pain (11.7%). On multivariable analysis, there was no association between outpatient surgery and 30-day readmission (3.9% vs. 4.1%; aOR 0.97, 95% CI 0.62–1.52, p = 0.908) or DSM (1.1% vs. 1.0%; aOR 0.91, 95%CI 0.36–2.29, p = 0.848). Kaplan–Meier analysis showed no difference in rates of hospital readmission between groups at 30-days from discharge (3.9% vs. 4.1%, p = 0.325).

Conclusions

Among patients undergoing elective LNF, there were no significant differences in post-operative complications and 30-day readmission when compared to traditional inpatient postoperative care. Further consideration should be given to transitioning LNF to an outpatient procedure.

Keywords: Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, Outpatient, Complications, Readmission

While proton pump inhibitors serve as an effective agent to control symptoms of gastro-esophageal reflux (GERD), laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery continues to be the standard of care for medically refractory disease and for patients hoping to avoid lifelong use of acid suppression medications [1–4]. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication (LNF) is the most commonly performed anti-reflux surgery and has traditionally been associated with a brief inpatient hospitalization [5]. Outpatient surgery has increased in popularity over the past two decades due in part to technological advances, improvement in analgesia, and development of specialized outpatient surgery centers [6, 7]. This shift has been expedited by other benefits associated with outpatient surgery, such as reduced costs, reduced length of stay, and increased patient satisfaction [8].

Several retrospective and prospective studies have addressed the feasibility and safety of outpatient LNF [6, 9–13]. Most available studies include a combination of LNF, laparoscopic Collis-Nissen, and laparoscopic Toupet [10–13] and demonstrate similar post-operative complication and readmission rates comparable to traditional inpatient hospitalization [14]. Thus, these results, coupled with the continued advancements in perioperative care, have shown that outpatient surgery may be a feasible option in well-selected patients.

While previous work has established the feasibility and safety of outpatient LNF, these studies have been limited by single surgeon or institution cohorts, relatively small sample sizes, and clustering of different surgical techniques within the cohort. A comprehensive national evaluation of outpatient versus inpatient LNF would provide more generalizable evidence regarding the short-term safety of outpatient LNF. The objectives of this retrospective observational cohort study were (1) to describe the frequency of outpatient LNF in a national cohort and (2) to identify differences in complications, including readmissions, between outpatient and inpatient LNF.

Methods

Data source

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (ACS NSQIP) was the data source for this study. ACS NSQIP sampling strategy, data abstraction, variables collected and outcomes are detailed elsewhere [15, 16]. Briefly, the ACS NSQIP database maintains prospectively collected data on several clinical and pathological characteristics. These include patient demographics, comorbidities, operative details, and 30-day post-operative outcomes. Data are collected by highly trained surgical clinical reviewers in a standardized fashion. This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University.

Study population

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes were used to identify patients who underwent LNF from 2012 to 2016 in the ACS-NSQIP database (CPT codes 43280 and 43325). Exclusion criteria included patients with American Society of Anesthesia (ASA) class V (n = 23), non-elective operations (n = 623), those with hospital stays that were missing or longer than 2 days post-operatively (n = 1687), and patients with missing readmission data (n = 237). Patients with length of stay greater than 2 days were excluded as this prolonged stay may indicate a postoperative complication or other deviation from the normal clinical pathway. Patient length of stay was defined as the number of days after the operation that the patient was in the hospital. Based on the length of stay, the outpatient cohort was defined as a group of patients who were discharged on the day of surgery (i.e. length of stay < 1 day), whereas the inpatient cohort was defined as a group of patients who were discharged on post-operatively day one or two (length of stay 1–2 days). 23-h observation status was included in the inpatient cohort.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes of interest included death or serious morbidity (DSM) and 30-day readmission. DSM included death, deep surgical site infection, organ space surgical site infection, wound dehiscence, pneumonia, reintubation, pulmonary embolism, acute kidney injury, myocardial infarct, cardiac arrest, sepsis, septic shock, return to OR, deep venous thrombosis, requiring ventilator support for 48 h, or bleeding requiring transfusion. Readmission diagnoses were identified using associated ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes.

Covariates

Patient demographic information (age, sex, race/ethnicity), operative characteristics (ASA, wound class, and operative time), as well as patient comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dyspnea on exertion, steroid use, and smoking status) were available as coded variables within the dataset. Smoking status was classified as “current smoker” or “non-smoker” based on patient-reported smoking within the last year.

Statistical analysis

Bivariate associations between outcome variables and patient characteristics (demographic, operative, comorbidities) were evaluated by Chi squared tests for categorical variables and two-sided t tests for continuous variables. A Kaplan–Meier failure function coupled with long-rank test for equality of survivor functions was used to further evaluate readmission by discharge day. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess for associations between the outcomes and outpatient surgery while controlling for possible confounders. The multivariable model adjusted for sex, age, race (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other/Unknown), body mass index (BMI), pre-existing comorbidities (COPD, steroid use, smoking status, and dyspnea), and ASA class. All tests were two sided and the level of significance was set at 0.05 Statistical analysis was performed using STATA v15.1 (College Station, TX).

Results

Among 7734 patients who underwent elective LNF from 2012 to 2016, 568 (7.3%) were in the outpatient cohort (Table 1). Patients receiving outpatient surgery were more likely to be male (41.9% vs. 36.1%, p = 0.005), self-report as a smoker (15.9% vs. 12.7%, p = 0.031), have an ASA classification of I or II (73.2% vs. 63.4%, p < 0.001), and have a shorter operative time (92.4 min vs. 111.9 min, p < 0.001). Patients in the inpatient cohort were more likely to have COPD (4.6% vs. 2.3%, p = 0.011), dyspnea on exertion or rest (9% vs. 4.9%, p = 0.001), and to actively use steroids (4.8% vs. 2.1%, p = 0.004).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of elective Nissen fundoplication patients by length of stay

| Outpatient N (%) |

Inpatient N (%) |

p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 568 (7.3) | 7166 (92.7) | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 34 (14.1) | 37 (14.4) | 0.067** |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 330 (58.1) | 4582 (63.9) | 0.005 |

| Male | 238 (41.9) | 2584 (36.1) | |

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 480 (84.5) | 6020 (84.0) | 0.329 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 26 (4.6) | 342 (4.8) | |

| Hispanic | 19 (3.4) | 343 (4.8) | |

| Unknown | 43 (7.6) | 461 (6.4) | |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | |||

| < 18.5 | 4 (0.7) | 39 (0.6) | 0.965 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 97 (17.2) | 1220 (17.1) | |

| 25–29.9 | 202 (35.8) | 2552 (35.7) | |

| > 30 | 261 (46.3) | 3332 (46.6) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 38 (6.8) | 584 (8.2) | 0.218 |

| Hypertension | 196 (34.5) | 2719 (37.9) | 0.104 |

| COPD | 13 (2.3) | 328 (4.6) | 0.011 |

| Dyspnea (moderate exertion/rest) | 28 (4.9) | 644 (9.0) | 0.001 |

| Steroid use | 12 (2.1) | 342 (4.8) | 0.004 |

| Current smoker | 90 (15.9) | 909 (12.7) | 0.031 |

| Functional status | |||

| Dependent | 6 (1.1) | 55 (0.8) | 0.454 |

| Independent | 649 (99.1) | 8351 (99.3) | |

| ASA | |||

| I/II | 416 (73.2) | 4544 (63.4) | <0.001 |

| III/IV | 152 (26.8) | 2622 (36.6) | |

| Wound classification | |||

| I/II | 565 (99.5) | 7110 (99.2) | 0.504 |

| III/IV | 3 (0.5) | 56 (0.8) | |

| Operative time, min, mean (SD) | 92.4 (1.8) | 111.9 (0.8) | <0.001** |

Chi squared test

t test

The overall rate of DSM was 1.0% and the overall 30-day readmission rate was 4.1%. A total of 22 patients (3.9%) in the outpatient cohort were readmitted within 30-days, compared to 294 of patients (4.1%) in the inpatient cohort (p = 0.799; Table 2). The most common readmission diagnoses overall were infectious complications (16.1%), dysphagia (12.9%), and abdominal pain (11.7%; Table 3). In regards to readmission diagnoses, higher rates of abdominal pain (18.2% vs. 11.2%), ileus (18.2% vs. 6.5%), and nausea and vomiting (22.7% vs. 7.5%) were observed in the outpatient cohort. The rate of DSM was low in both groups, with 6 patients (1.1%) experiencing DSM in the outpatient cohort and 73 (1%) in the inpatient cohort (p = 0.932). On multivariable analysis, outpatient surgery was not associated with higher 30-day readmission (3.9% vs. 4.1%; aOR 0.97, 95% CI 0.62–1.52, p = 0.908) or DSM (1.1% vs. 1.0%; aOR 0.91, 95% CI 0.36–2.29, p = 0.848).

Table 2.

Death and serious morbiditya and 30-day readmission rate by length of stay

| Outpatient N (%) |

Inpatient N (%) |

p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted univariate | |||

| 30-day readmission | 22 (3.9) | 294 (4.1) | 0.799* |

| Death and serious morbidity | 6 (1.1) | 73 (1.0) | 0.932* |

| Adjusted multivariable modelb | aOR (95% CI) | ||

| 30-day readmission | 0.91 (0.36–2.29) | REF | 0.848 |

| Death and serious morbidity | 0.97 (0.62–1.52) | REF | 0.908 |

aOR Adjusted odds ratio, CI Confidence Interval

Chi squared test

Death and serious morbidity includes infectious, cardiovascular, pulmonary, thromboembolic or renal complications

Multivariable model adjusted for sex, age, race (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other/Unknown), body mass index (BMI), pre-existing comorbidities (COPD, steroid use, smoking status, and dyspnea), and ASA class

Table 3.

Readmission diagnosis by length of stay

| Total (%) | Outpatient (%) | Inpatient (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |||

| Infectious complication | 51 (16.1) | 3 (13.6) | 48 (16.3) |

| Dysphagia | 41 (12.9) | 2 (9.1) | 39 (13.3) |

| Abdominal pain | 37 (11.7) | 4 (18.2) | 33 (11.2) |

| Other | 36 (11.4) | 1 (4.6) | 35 (11.9) |

| N/V | 27 (8.5) | 5 (22.7) | 22 (7.5) |

| Ileus | 23 (7.3) | 4 (18.2) | 19 (6.5) |

| Dehydration | 21 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (7.1) |

| VTE | 8 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (2.7) |

| Wound complication | 6 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (2.0) |

| GERD | 6 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (2.0) |

| Unknown | 60 (18.9) | 3 (13.6) | 57 (19.4) |

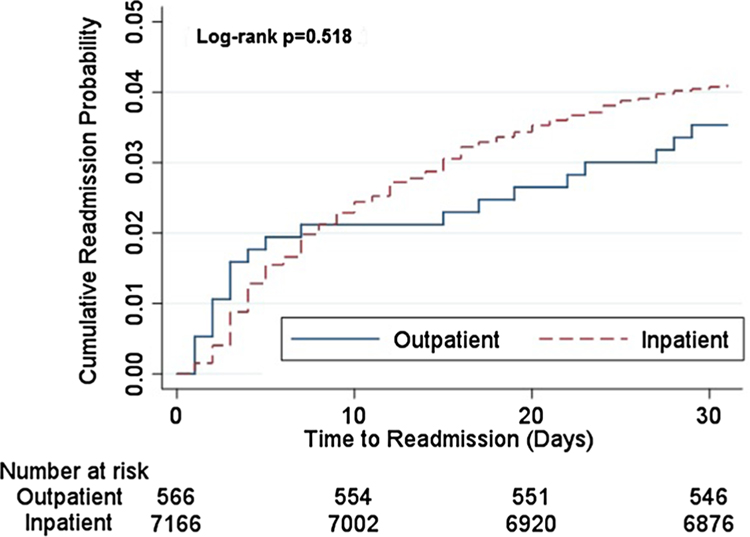

Further analysis of readmissions using Kaplan–Meier failure function and log-rank test for equality of survivors demonstrated no significant difference in readmissions at 30 days (p = 0.518; Fig. 1). However, the rate of readmission within the first 10 days following surgery did appear to be slightly higher following outpatient procedures as compared with inpatient postoperative care. This higher rate appears to reverse following the 10-day mark, leading to an overall lack of significant difference between the two groups.

Fig. 1.

Time (days) to readmission using Kaplan–Meier Methods

Discussion

In this study, a national cohort of patients undergoing LNF was analyzed to compare outcomes following outpatient and inpatient surgery. Outpatient surgery was generally performed in healthier patients. There were no significant differences in post-operative DSM or 30-day readmission between elective outpatient and inpatient LNF.

Previous single surgeon and institutional studies seeking to determine the feasibility of outpatient LNF have demonstrated post-operative complication rates ranging from 3 to 22%. Similarly, the 30-day readmission rates among those discharged on the day of surgery have ranged from 1 to 11% [10–13, 17, 18]. The results from our study of a national cohort suggest a lower complication rate (1%) and a similar 30-day readmission rate (3.9%) among patients undergoing outpatient LNF. These rates are also comparable to the rates of post-operative complications and readmissions in those undergoing LNF with traditional inpatient hospitalization as seen in previous studies [14]. Taken together, these results suggest that outpatient LNF is a viable option for selected patients undergoing this procedure.

It is likely that the choice between outpatient and inpatient hospitalization itself is a reflection of surgeon clinical judgement and assessment of patient risk. Differences in patient comorbidities play a critical role in the decision to admit a patient following an elective LNF, as seen in Table 1. Furthermore, the significant difference noted in operative time between the outpatient and inpatient cohorts may reflect differences in patient comorbidities, complexity of case, or surgeon experience. Each of these factors would also play an important role in the surgeon’s decision to admit or discharge a patient. The lack of statistically significant differences between outpatient and inpatient 30-day readmission and DSM on univariate as well as in the subsequent multivariable models suggest that surgeons are making informed decisions regarding both length of stay and the selective use of outpatient surgery in these patients. Perhaps more important, these decisions were not associated with a significant difference in post-operative outcomes.

Separately from the absolute rate of readmission, we found different timelines and patterns of readmission between outpatient and inpatient LNF. While the overall rate of 30-day readmission was not significantly different between groups, the results of the Kaplan–Meier analysis of hospital readmission indicate that there is a slightly higher rate of early readmission among those undergoing outpatient procedures. This higher early rate of readmission may be due to immediate post-operative events that would otherwise be treated during the traditional inpatient admission. Further examination of readmission diagnoses demonstrates that patients in the outpatient group experience higher rates of readmission for diagnoses of abdominal pain (18.2% vs. 11.2%) and nausea or vomiting (13.6% vs. 5.4%), similar to a previous study [18]. Both of these diagnoses are potentially avoidable causes of readmission. These findings may inform the future development of targeted interventions, such as those included in many described enhanced recovery pathways, to reduce the likelihood of early readmission for abdominal pain and nausea and vomiting following outpatient LNF. As such, future research should focus on the use of targeted interventions including the use of structured preoperative patient education tools, non-narcotic analgesia, and patient-reported outcomes.

This study should be interpreted in light of some discrete limitations. First, the retrospective nature of this analysis allows for the examination of association between discharge timing and studies outcomes, but does not enable the precise causal relationship to be determined. Second, ACS NSQIP only reports 30-day post-operative outcomes and does not include detailed information regarding length of stay for subsequent readmissions. This precludes detailed evaluation each readmission episode as well as long-term morbidity following outpatient LNF. Third, LNF is a relatively safe operation with few post-operative complications. This low number of events may make it difficult to identify statistically significant differences between groups. Additionally, the outpatient and inpatient cohorts, have an inherent difference in exposure time for potential readmission. That is, those who are inpatients for 1 or 2 days could not experience a readmission during that time. This introduces an immortal time bias that may skew results, making it appear as though the outpatient cohort experienced higher 30-day readmission rates [19]. Despite this potential bias, we found that within 10 days of discharge, when all patients would be at risk for an equal time interval, there was a higher readmission rate for outpatient compared to inpatient readmissions. Finally, readmission diagnoses were unknown for 18.9% of patients who were readmitted. Thus, actual readmission diagnoses between outpatient and inpatient cohorts may vary.

Conclusion

In this retrospective national study, performing LNF as an outpatient procedure was not associated with an increase in perioperative complications or 30-day readmission. However, a small increase in early readmission following same day discharge may be present following outpatient LNF. Outpatient LNF can be safely employed in appropriately selected patients, and perioperative interventions including improved post-discharge monitoring focused on abdominal pain along with prevention of nausea and vomiting may provide an opportunity to improve readmission rates following outpatient LNF.

Acknowledgments

Views expressed in this work represent those of the authors only. TKY and RJE (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ] 5T32HS000078) were supported by a postdoctoral research fellowship. RPM is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K12HS023011) and an Institutional Research Grant from the American Cancer Society (IRG-18-163-24).

Footnotes

This work will be presented as a poster at the 2019 Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons Meeting.

Compliance with ethical standards

Disclosures Drs. Yuce, Ellis, Merkow, Soper, Bilimoria, and Odell have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to report, related to this work.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dallemagne B, Perretta S (2011) Twenty years of laparoscopic fundoplication for GERD. World J Surg 35(7):1428–1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frazzoni M et al. (2014) Laparoscopic fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 20(39):14272–14279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nijjar RS et al. (2010) Five-year follow-up of a multicenter, double-blind randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Nissen vs anterior 90 degrees partial fundoplication. Arch Surg 145(6):552–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross SB et al. (2013) Late results after laparoscopic fundoplication denote durable symptomatic relief of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Surg 206(1):47–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickinson KJ et al. (2016) Factors influencing length of stay after surgery for benign foregut disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 50(1):124–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molina JC et al. (2018) Same day discharge for benign laparoscopic hiatal surgery: a feasibility analysis. Surg Endosc 32(2):937–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng R, Mullin EJ, Maddern GJ (2005) Systematic review of day-case laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. ANZ J Surg 75(3):160–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gronnier C et al. (2014) Day-case versus inpatient laparoscopic fundoplication: outcomes, quality of life and cost-analysis. Surg Endosc 28(7):2159–2166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey ME et al. (2003) Day-case laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Br J Surg 90(5):560–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finley CR, McKernan JB (2001) Laparoscopic antireflux surgery at an outpatient surgery center. Surg Endosc 15(8):823–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narain PK, Moss JM, DeMaria EJ (2000) Feasibility of 23-hour hospitalization after laparoscopic fundoplication. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 10(1):5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray S (2003) Result of 310 consecutive patients undergoing laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication as hospital outpatients or at a free-standing surgery center. Surg Endosc 17(3):378–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trondsen E et al. (2000) Day-case laparoscopic fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Br J Surg 87(12):1708–1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pohl D et al. (2001) Management and outcome of complications after laparoscopic antireflux operations. Arch Surg 136(4):399–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen ME et al. (2013) Optimizing ACS NSQIP modeling for evaluation of surgical quality and risk: patient risk adjustment, procedure mix adjustment, shrinkage adjustment, and surgical focus. J Am Coll Surg 217(2):336–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ingraham AM et al. (2010) Quality improvement in surgery: the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program approach. Adv Surg 44:251–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mariette C et al. (2007) The safety of the same-day discharge for selected patients after laparoscopic fundoplication: a prospective cohort study. Am J Surg 194(3):279–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vlug MS et al. (2009) Feasibility of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication as a day-case procedure. Surg Endosc 23(8):1839–1844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones M, Fowler R (2016) Immortal time bias in observational studies of time-to-event outcomes. J Crit Care 36:195–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]