Abstract

Objectives

While the safety of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs in COVID‐19 has been questioned, they may be beneficial given the hyper‐inflammatory immune response associated with severe disease. We aimed to assess the safety and potential efficacy of cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) selective inhibitors in high‐risk patients.

Methods

Retrospective study of patients with COVID‐19 pneumonia and aged ≥ 50 years who were admitted to hospital. Adverse outcomes analysed included supplemental oxygen use, intensive care unit admission, mechanical ventilation and mortality, with the primary endpoint a composite of any of these. Plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were measured in a subset.

Results

Twenty‐two of 168 (13.1%) in the cohort received COX‐2 inhibitors [median duration 3 days, interquartile range (IQR) 3–4.25]. Median age was 61 (IQR 55–67.75), 44.6% were female, and 72.6% had at least one comorbidity. A lower proportion of patients receiving COX‐2 inhibitors met the primary endpoint: 4 (18.2%) versus 57 (39.0%), P = 0.062. This difference was less pronounced after adjusting for baseline difference in age, gender and comorbidities in a multivariate logistic regression model [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 0.45, 95% CI 0.14–1.46]. The level of interleukin‐6 declined after treatment in five of six (83.3%) treatment group patients [compared to 15 of 28 (53.6%) in the control group] with a greater reduction in absolute IL‐6 levels (P‐value = 0.025).

Conclusion

Treatment with COX‐2 inhibitors was not associated with an increase in adverse outcomes. Its potential for therapeutic use as an immune modulator warrants further evaluation in a large randomised controlled trial.

Keywords: COVID‐19, COX‐2 inhibitors, interleukin‐6, SARS‐CoV‐2

We conducted a retrospective study of 168 COVID‐19 patients aged ≥ 50 years with pneumonia, 22 (13.1%) of whom received cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) inhibitor treatment. Patients receiving COX‐2 inhibitors had a lower rate of adverse outcomes: 4 (18.2%) versus 57 (39.0%), P = 0.062. Measurement of cytokine levels in following treatment, measurements of cytokine levels, five of six patients (83.3%) from the treatment group had a reduction in interleukin‐6 after treatment, which was not seen in the control group.

![]()

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic has placed a significant strain on healthcare systems, especially scarce intensive care unit (ICU) resources. Up to five per cent of patients develop critical illness requiring ICU care 1 and demand outstripping ICU resource capacity has contributed to significant increases in case fatality rates in some settings. 2 Treatments to reduce the risk of progression to severe disease are important to mitigate this pressure on resource availability and reduce mortality. To date, the only drug that has proven effective in a Phase 3 randomised controlled trial is remdesivir 3 , 4 ; however, its intravenous formulation limits its broader use in both outpatient settings and inpatients with milder disease at presentation. A broader range of therapeutics, including an oral drug that can be prescribed for ambulatory patients to reduce the risk of progression to severe disease, is still required to fill this gap in the COVID‐19 armamentarium.

Severe COVID‐19 is associated with a dysregulated hyper‐inflammatory immune response, with previous studies finding elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in patients with severe disease. 5 , 6 Interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) has been identified as a key cytokine in this inflammatory cascade. 7 , 8 This immunopathogenesis of COVID‐19 suggests that immunomodulators may be beneficial as an adjunct or alternative to antivirals. 5

The use of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in the treatment of COVID‐19 has generated controversy, with contradictory recommendations from various regulatory authorities. 9 A rapid review by the WHO found no evidence to establish the safety or efficacy of NSAIDs for COVID‐19. 10 Furthermore, much of the discussion has over‐looked NSAIDs selective for the inducible cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) enzyme. 9 COX‐2 inhibitors (such as etoricoxib or celecoxib) are one of the few treatments available with RCT evidence of mortality reduction in severe influenza. 11

We hypothesised that COX‐2 inhibitors are safe in the treatment of COVID‐19, and may be associated with a reduction in adverse outcomes in high‐risk older patients with pneumonia, primarily through attenuation of the hyper‐inflammatory immune response associated with severe disease.

Results

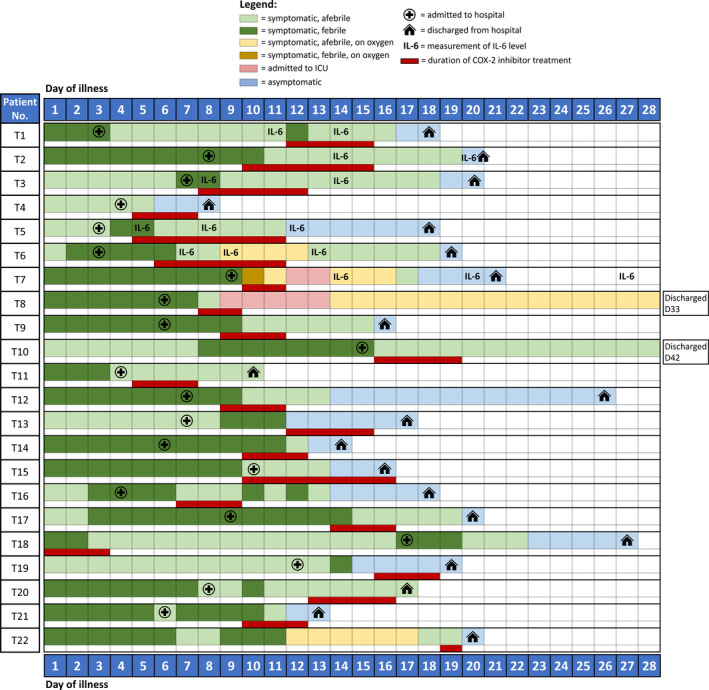

In all, 1588 patients were admitted during the study period and were screened; 168 (10.6%) patients met inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. The other patients were excluded based on age < 50 years or the absence of pneumonia on chest radiograph on admission. As all patients with confirmed COVID‐19 infection were admitted in accordance with national policy during this period, there was a large proportion of young patients with limited upper respiratory tract involvement who did not fulfil the inclusion criteria. Twenty‐two (13.1%) patients in the study cohort received at least a single dose of etoricoxib; 12 received 60 mg once daily, and ten received 90 mg once daily. Median treatment duration was 3 days [range 1–7, interquartile range (IQR) 3–4.25], and median day of initiation was day 10 of illness (range 1–19, IQR 6.75–12.25). The detailed clinical course of all patients in the treatment group, including timing and duration of COX‐2 inhibitor treatment, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Clinical course in relation to timing and duration of COX‐2 inhibitor treatment.

The treatment group was significantly younger (median age 56 years, IQR 53.8–61) and had fewer comorbidities (median number of comorbidities 1, IQR 0–2; Charlson's score 0, IQR 0–0.25) compared with the control group (median age 62, IQR 55.8–68.3; number of comorbidities 2, IQR 0.75–3; Charlson's score 0.5, IQR 0–1) (Table 1). However, there were no statistically significant differences in known laboratory biomarkers for severe infection, including baseline neutrophil and lymphocyte counts, C‐reactive protein (CRP) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). 12 No patient in the treatment group required invasive or non‐invasive ventilation or was in the ICU when they first received COX‐2 inhibitor treatment.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and adverse outcomes of patients with and without COX‐2 inhibitor treatment

| Variable | COX‐2 inhibitor treatment (n = 22) | No COX‐2 inhibitor treatment (n = 146) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 56 (53.8–61.0) | 62 (55.8–68.3) | 0.002 |

| Male gender | 11 (50.0%) | 82 (56.2%) | 0.649 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (18.2%) | 46 (31.5%) | 0.316 |

| Hypertension | 7 (31.8%) | 74 (50.7%) | 0.113 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 1 (4.5%) | 14 (9.6%) | 0.696 |

| Chronic lung disease | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (2.7%) | 0.432 |

| Smoking | 1 (4.8%) | 4 (2.8%) | 0.651 |

| Number of comorbidities | 1 (0–2) | 2 (0.75–3) | 0.010 |

| Charlson's score | 0 (0–0.25) | 0.5 (0–1) | 0.018 |

| Baseline investigations | |||

| White blood count (×109 L−1) | 4.45 (3.40–6.10) | 5.15 (4.10–6.60) | 0.082 |

| Neutrophil count (×109 L−1) | 3.04 (2.09–4.62) | 3.23 (2.44–4.59) | 0.513 |

| Lymphocyte count (×109 L−1) | 0.94 (0.78–1.15) | 1.12 (0.81–1.44) | 0.100 |

| C‐reactive protein (mg L−1) | 16.2 (10.3–24.8) | 28.2 (8.4–63.2, n = 143) | 0.129 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U L−1) | 524 (409.8–645) | 509 (418.5–685) | 0.994 |

| Creatinine (μmol L−1) | 67.5 (53.3–84.3) | 73.0 (59.0–87.0) | 0.198 |

| Co‐administered treatments | |||

| Lopinavir–ritonavir | 2 (9.1%) | 37 (25.3%) | 0.109 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (6.2%) | 0.608 |

| Remdesivir | 1 (4.5%) | 17 (11.6%) | 0.473 |

| Interferon‐beta | 1 (4.5%) | 13 (8.9%) | 0.697 |

| Adverse outcomes | |||

| Supplemental oxygen | 4 (18.2%) | 56 (38.4%) | 0.093 |

| ICU admission | 2 (9.1%) | 32 (21.9%) | 0.254 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0 (0.0%) | 19 (13.0%) | 0.139 |

| Mortality | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (5.6%) | 0.599 |

| Composite adverse outcome | 4 (18.2%) | 57 (39.0%) | 0.062 |

Continuous variables are reported as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables are reported as absolute number (percentage).

Bold text indicates P < 0.05.

CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; NA, not applicable.

Apart from COX‐2 inhibitor treatment, the use of other co‐administered treatments was heterogenous in the study cohort. As there were no proven effective therapies during the study period, a variety of agents including lopinavir–ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine and interferon‐beta were prescribed on an off‐label basis by managing physicians. Eighteen patients received remdesivir as part of ongoing clinical trials during the study period. There were no statistically significant differences in the use of these other treatments between the treatment and control groups.

There were no statistically significant differences in the individual adverse outcomes (requirement for supplemental oxygen, ICU admission, mechanical ventilation or mortality), although the overall incidence of the composite outcome was substantially lower in the COX‐2 treatment group: 4 (18.2%) versus 57 (39%), P‐value = 0.062 (Table 1). No patient in the treatment group developed adverse drug reactions from COX‐2 inhibitors, including gastrointestinal, renal or cardiovascular complications.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis to adjust for baseline differences between treatment and control groups did not find a statistically significant difference in the composite adverse outcome with COX‐2 inhibitor treatment (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.45, 95% CI 0.14–1.46). There were also no significant differences associated with composite adverse outcome by age, male gender or Charlson's score, although there was a significant association with hypertension (AOR 2.05, 95% CI 1.04–4.06) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis for factors associated with composite adverse outcome

| Variable | Univariate logistic regression analysis | Multivariate logistic regression analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P‐value | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P‐value | |

| Age | 1.04 (1.00–1.07) | 0.032 | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.321 |

| Male gender | 1.26 (0.67–2.39) | 0.472 | 1.17 (0.59–2.31) | 0.652 |

| Hypertension | 2.46 (1.29–4.69) | 0.006 | 2.05 (1.04–4.06) | 0.039 |

| Charlson's score | 1.24 (0.95–1.63) | 0.119 | 1.04 (0.77–1.39) | 0.819 |

| COX‐2 inhibitor treatment | 0.35 (0.11–1.08) | 0.067 | 0.45 (0.14–1.46) | 0.185 |

The Hosmer and Lemeshow test for multivariate model, P = 0.751.

Bold text indicates P < 0.05.

CI, confidence interval.

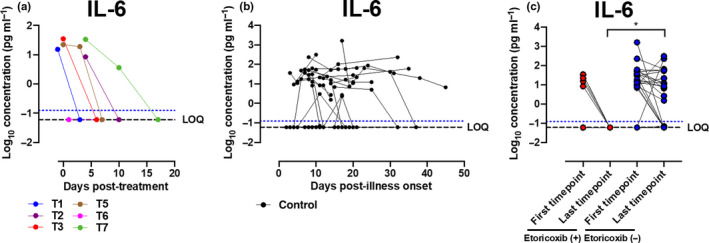

Plasma samples were analysed longitudinally during admission for 34 patients, including six who received COX‐2 inhibitor treatment, and 28 who did not. Among patients who received COX‐2 inhibitor treatment, samples were first measured prior to treatment in one patient, and up to 5 days post‐commencement of treatment in five patients. Median day of illness of first timepoint was day 9.5 (IQR 6.5–14.0) in the treatment group and day 9 (IQR 5.25–14.5) in the control group (P‐value = 0.821, Mann–Whitney U‐test). Median day of illness of last timepoint was day 14 (IQR 12.75–21.75) in the treatment group and day 18 (IQR 12.0–25.0) in the control group (P‐value = 0.635, Mann–Whitney U‐test). Serial measurement of plasma samples showed reduction in the level of a key pro‐inflammatory cytokine, interleukin‐6 (IL‐6), after COX‐2 inhibitor treatment in majority (five of six; 83.3%) of patients in the treatment group, with median (IQR) IL‐6 level of 18.86 (10.16–30.86) pg mL−1 at the first timepoint, and median (IQR) IL‐6 level of 0.06 (0.06–0.06) pg mL−1 at the last timepoint after treatment (median delta IL‐6 level of 18.80 pg mL−1) (Figure 2a). In contrast, a reduction in IL‐6 was observed in approximately half (15 of 28, 53.6%) of patients in the control group, with median (IQR) IL‐6 level of 11.99 (0.06–36.86) pg mL−1 at the first timepoint, and median (IQR) IL‐6 level of 2.11 (0.06–15.10) pg mL−1 at the last timepoint (Figure 2b and c). Change in IL‐6 level was significantly different comparing treatment and control groups (P‐value = 0.025, Mann–Whitney U‐test) (Figure 2c). Other inflammatory cytokines and chemokines measured did not show uniform changes among the six patients after COX‐2 inhibitor treatment, and their median levels are shown in Table 3. Timing of sample collection of IL‐6 levels is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal profile of plasma IL‐6 levels in patients with and without COX‐2 inhibitor treatment. Concentrations of 45 immune mediators were quantified using a 45‐plex microbead‐based immunoassay. (a) Cytokine levels were measured in the plasma fractions of COVID‐19 pneumonia patients aged ≥ 50 who received etoricoxib treatment (n = 6) at multiple timepoints and showed reduction in IL‐6 level in five of six patients. (b) Serial plasma cytokine levels were also monitored in COVID‐19 pneumonia patients aged ≥ 50 in the control group (n = 28) during illness progression. (c) Plasma samples from the first and last timepoints were also analysed from COVID‐19 pneumonia patients aged ≥ 50 in the control group (n = 28). IL‐6 profiles were compared between treatment and control groups. Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann–Whitney U‐test (*P < 0.05). Patient samples that are not detectable are assigned the value of logarithm transformation of limit of quantification (LOQ). Cytokine level for healthy controls (n = 13) is indicated by the blue dotted line.

Table 3.

Concentrations of immune mediators in subset of patients (n = 34)

| No | Immune mediator |

No COX‐2 inhibitor treatment (n = 28) Median concentration, pg mL−1 |

COX‐2 inhibitor treatment (n = 6) Median concentration, pg mL−1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First timepoint | Last timepoint | Difference | First timepoint | Last timepoint | Difference | ||

| 1 | BDNF | 16.21 | 21.42 | 5.21 | 28.38 | 19.84 | 8.54 |

| 2 | EGF | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 1.66 | 0.17 | 1.49 |

| 3 | Eotaxin | 17.74 | 14.77 | 2.97 | 9.55 | 10.53 | 0.98 |

| 4 | FGF‐2 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.00 |

| 5 | GM‐CSF | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.00 |

| 6 | GRO‐alpha | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 1.02 | 0.05 | 0.97 |

| 7 | HGF | 164.80 | 133.10 | 31.7 | 59.91 | 45.37 | 14.54 |

| 8 | IFN‐alpha | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 0.98 |

| 9 | IFN‐gamma | 8.55 | 5.78 | 2.77 | 13.50 | 6.95 | 6.55 |

| 10 | LIF | 4.97 | 4.59 | 0.38 | 3.56 | 4.99 | 1.43 |

| 11 | MCP‐1 | 67.62 | 57.41 | 10.21 | 92.72 | 48.17 | 44.55 |

| 12 | MIP‐1 alpha | 1.92 | 2.00 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 1.11 | 1.00 |

| 13 | MIP‐1 beta | 39.16 | 41.12 | 1.96 | 34.49 | 41.33 | 6.84 |

| 14 | PDGF‐BB | 20.03 | 35.01 | 14.98 | 20.23 | 59.75 | 39.52 |

| 15 | PIGF‐1 | 1.52 | 4.92 | 3.40 | 0.19 | 4.72 | 4.53 |

| 16 | RANTES | 29.71 | 36.56 | 6.85 | 24.08 | 45.76 | 21.68 |

| 17 | SCF | 4.32 | 4.43 | 0.11 | 3.91 | 3.67 | 0.24 |

| 18 | SDF‐1 alpha | 598.10 | 665.70 | 67.6 | 510.90 | 667.00 | 156.10 |

| 19 | IP‐10 | 49.93 | 18.30 | 31.63 | 66.44 | 21.50 | 44.94 |

| 20 | TNF‐alpha | 5.97 | 5.28 | 0.69 | 4.25 | 6.82 | 2.57 |

| 21 | TNF‐beta | 2.98 | 2.98 | 0.00 | 2.98 | 2.98 | 0.00 |

| 22 | VEGF‐A | 131.40 | 145.20 | 13.8 | 102.50 | 159.50 | 57.00 |

| 23 | VEGF‐D | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 4.42 | 4.68 | 0.26 |

| 24 | bNGF | 0.26 | 0.75 | 0.49 | 1.62 | 1.03 | 0.59 |

| 25 | IL‐1 alpha | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.67 | 0.66 |

| 26 | IL‐1 beta | 1.71 | 1.98 | 0.27 | 1.36 | 2.34 | 0.98 |

| 27 | IL‐1RA | 861.10 | 623.40 | 237.70 | 916.00 | 821.10 | 94.90 |

| 28 | IL‐2 | 13.87 | 13.50 | 0.37 | 11.62 | 9.72 | 1.90 |

| 29 | IL‐4 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.00 |

| 30 | IL‐5 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| 31 | IL‐8 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.00 |

| 32 | IL‐9 | 2.35 | 2.35 | 0.00 | 2.35 | 2.35 | 0.00 |

| 33 | IL‐7 | 0.44 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 1.44 | 0.60 | 0.84 |

| 34 | IL‐10 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| 35 | IL‐12p70 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 1.16 | 0.87 | 0.29 |

| 36 | IL‐13 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| 37 | IL‐15 | 2.48 | 1.12 | 1.36 | 1.07 | 3.83 | 2.76 |

| 38 | IL‐17A | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 1.72 | 1.64 |

| 39 | IL‐18 | 80.14 | 47.03 | 33.11 | 52.58 | 32.82 | 19.76 |

| 40 | IL‐21 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.00 |

| 41 | IL‐22 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.00 |

| 42 | IL‐23 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.00 |

| 43 | IL‐27 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 8.50 | 7.51 |

| 44 | IL‐31 | 2.69 | 2.69 | 0.00 | 2.69 | 2.69 | 0.00 |

Discussion

In this population at increased risk of severe COVID‐19 (≥ 50 years old and with radiographic pneumonia), there was no evidence that COX‐2 inhibitor treatment was associated with an increase in adverse outcomes, supporting the use of short duration therapy in COVID‐19 for symptom relief and as an anti‐pyretic. The finding that patients in the treatment group had fewer adverse outcomes including a non‐significant reduction in progression to supplemental oxygen, invasive mechanical ventilation or death is intriguing but must be interpreted with caution.

First, the group receiving COX‐2 inhibitors was younger and had fewer comorbidities—even if there were no evident differences in laboratory biomarkers for severe disease including neutrophil and lymphocyte counts, CRP and LDH. Unmeasured confounding may explain some of the differences in outcome if it introduced systematic bias into which patients received COX‐2 inhibitors. Although there was no significant difference in the proportion of diabetes mellitus between intervention groups, we did not record quantitative measures such as the degree control of diabetic control. Patients in the treatment group may have had less diabetic nephropathy or fewer vascular complications and hence been assessed by the managing physician as better able to tolerate COX‐2 inhibitors.

Second, this is a small retrospective study, which limits the generalisability of our findings. Although there were a large number of patients with confirmed COVID‐19 admitted during the study period, only a small proportion (10.6%) met the inclusion criteria and were including in the data analysis. As a result of the small sample size, it was only powered to detect large differences in clinical outcomes. Smaller but clinically relevant differences in outcomes would not be identified as statistically significant.

Third, sample collection for IL‐6 levels was not done systematically before and after intervention, as cytokine analysis was carried out as part of a separate observational study, and only retrospectively correlated to COX‐2 inhibitor treatment in this study. Some patients (T2 and T7) in the treatment group had IL‐6 levels measured only 4 days after initiation of COX‐2 treatment, and it is thus difficult to be sure that this reduction in IL‐6 can be attributable to COX‐2 inhibitor treatment. With the small sample size for IL‐6 measurements in the treatment group, these IL‐6 data are primarily descriptive and exploratory, and further study is required to establish a clear correlation between COX‐2 inhibitor treatment and its impact on IL‐6 levels in COVID‐19.

Fourth, we did not assess the effect of co‐administered treatments including other antivirals or immunomodulators. As the use of these other agents was heterogenous in the study population, we did not account for the interactions between co‐administered treatments and COX‐2 inhibitor treatment in the multivariate model.

Despite these limitations, the results indicate a possible signal towards clinical benefit, which is supported by a biologically plausible physiologic mechanism and a detailed analysis of a subset of six patients in the treatment group. This provides an impetus for further analysis in a larger prospective clinical trial.

The dysregulated immune response associated with severe COVID‐19 is well characterised, with multiple studies showing elevated serum levels of inflammatory cytokines in patients with severe disease and mortality. 5 , 6 , 13 Post‐mortem studies have confirmed that immune‐mediated lung injury underlies the pathogenesis of severe pneumonitis seen in some patients. 14 COVID‐19 infection has also been associated with endotheliitis because of direct viral infection of endothelial cells and the host inflammatory response. 15

While only six patients in the treatment group had measurements of serial plasma IL‐6, a reduction in IL‐6 levels after treatment is promising, given the association of elevated IL‐6 with severe disease. 5 , 8 We postulate that a reduction in pro‐inflammatory immune response may be associated with reduced lung damage, resulting in fewer adverse outcomes and reducing risk of progression to severe disease.

The COX‐2 enzyme has been shown to be hyper‐induced in the pro‐inflammatory cascade in influenza, 16 and use of COX‐2 inhibitors was associated with reduction in IL‐6 and IL‐10 levels, incidence of ventilator‐associated pneumonia and mortality in a randomised controlled trial. 11 , 17 Its use in influenza is further supported by in vitro and murine models. 18 , 19 COX‐2 inhibitor treatment has also been shown to reduce IL‐6 levels in other non‐infective inflammatory diseases such as inflammatory arthritis and pancreatitis. 20 , 21 These provide a biologic basis for its potential efficacy in other respiratory viruses whereby pathophysiology is driven by similar inflammatory states, such as in COVID‐19.

In conclusion, COX‐2 inhibitors are an attractive intervention in COVID‐19 for relief of symptoms and fever given their low cost, wide availability and potential for beneficial immune modulation. We did not find that COX‐2 inhibitors increased the risk of severe COVID‐19 in a population of older adults with pneumonia, but found evidence of beneficial reduction in inflammatory cytokines. The trend to a reduction in adverse outcomes with COX‐2 inhibitors provides the rationale for an adequately powered randomised controlled trial to further elaborate on safety and to examine whether they may attenuate disease severity in COVID‐19.

Methods

Clinical data

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all patients with COVID‐19 infection confirmed by SARS‐CoV‐2 polymerase chain reaction assay and admitted to the National Centre for Infectious Diseases, Singapore, from 22 January to 4 April 2020. Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 50 years old and pneumonia diagnosed on chest radiography. As need for supplemental oxygen therapy was part of the primary endpoint, requiring supplemental oxygen on admission was an exclusion criterion.

Clinical data were collected by study investigators from medical records. Informed consent for data collection was waived as part of an outbreak investigation authorised by the Ministry of Health, Singapore, under the Infectious Diseases Act. Adverse outcomes analysed were hypoxia requiring supplemental oxygen (oxygen saturation < 94% on room air), ICU admission, mechanical ventilation and mortality. The primary endpoint was a composite of these (having any of these adverse outcomes). Data were collected up until discharge or death.

Immunological profiling

Independently from the retrospective study, clinical data and serial blood samples were collected from a subgroup of hospitalised individuals with PCR confirmed COVID‐19 who participated in the observational PROTECT study. This COVID‐19 characterisation protocol was approved by the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board, Study Reference 2012/00917. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants for sample collection. These patients formed a subset of the above group of patients identified after application of the inclusion criteria, and were identified by cross‐checking the list of included patients with the PROTECT study database.

Plasma samples were tested for cytokine levels to assess evolution of the inflammatory response. Briefly, serial plasma samples were tested for immune mediator levels using Cytokine/Chemokine/Growth Factor 45‐Plex Human ProcartaPlex™ Panel 1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Samples were treated by solvent/detergent treatment based on Triton™ X‐100 (1%) for virus inactivation. 22 Standards and plasma from COVID‐19 patients and healthy controls were incubated with fluorescent‐coded magnetic beads pre‐coated with respective capture antibodies in a 96 black clear‐bottom plate. After washing, biotinylated detection antibodies were incubated with the cytokine‐bound beads for 1 h. Finally, streptavidin‐PE was added and incubated for another 30 min. Measurements were acquired on the FLEXMAP® 3D (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX, USA) using xPONENT® 4.0 (Luminex) acquisition software. Data analysis was done on Bio‐Plex Manager™ 6.1.1 (Bio‐Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Standard curves were generated with a 5‐PL (5‐parameter logistic) algorithm, reporting values for both MFI and concentration data.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared using the Chi‐square or Fisher's exact tests as appropriate, and continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U‐test. P‐value < 0.05 was considered significant. A multivariable logistic regression model was constructed to evaluate factors associated with the composite adverse outcome. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). No pre‐determined sample size calculation was performed as this was a retrospective cohort study.

Internal control samples were included in each Luminex assay to remove any potential plate effects. Readouts of these samples were then used to normalise the assayed plates. A correction factor was obtained from the differences observed across the multiple assays, and this correction factor was then used to normalise all the samples. The concentrations were logarithmically transformed to ensure normality. Samples with concentration out of measurement range were assigned the value of logarithmic transformation of Limit of Quantification (LOQ). Plots were generated using GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Sean Wei Xiang Ong: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Visualization; Writing‐original draft; Writing‐review & editing. Wilnard Yeong Tze Tan: Data curation. Yi‐Hao Chan: Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Visualization; Writing‐original draft; Writing‐review & editing. Siew‐Wai Fong: Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Visualization; Writing‐original draft; Writing‐review & editing. Laurent Renia: Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Writing‐review & editing. Lisa FP Ng: Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Writing‐review & editing. Yee‐Sin Leo: Funding acquisition; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Writing‐review & editing. David Chien Lye: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Writing‐review & editing. Barnaby Edward Young: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Writing‐original draft; Writing‐review & editing.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the NMRC COVID‐19 Research Fund (COVID19RF‐001). The funding sources had no role in study design, data analysis and collection, interpretation of results or decision to submit the paper for publication.

References

- 1. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak in china: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020; 323: 1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ji Y, Ma Z, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q. Potential association between COVID‐19 mortality and health‐care resource availability. Lancet Glob Health 2020; 8: e480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE et al Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid‐19 ‐ preliminary report. N Engl J Med 2020. e‐pub ahead of print. 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldman JD, Lye DCB, Hui DS et al Remdesivir for 5 or 10 days in patients with severe Covid‐19. N Engl J Med 2020. e‐pub ahead of print. 10.1056/NEJMoa2015301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z et al Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis 2020; ciaa248 e‐pub ahead of print. 10.1093/cid/ciaa248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R et al Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395: 1054–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID‐19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 846–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen X, Zhao B, Qu Y et al Detectable serum SARS‐CoV‐2 viral load (RNAaemia) is closely correlated with drastically elevated interleukin 6 (IL‐6) level in critically ill COVID‐19 patients. Clin Infect Dis 2020; ciaa449 e‐pub ahead of print. 10.1093/cid/ciaa449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. FitzGerald GA. Misguided drug advice for COVID‐19. Science 2020; 367: 1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization . The use of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in patients with COVID‐19. [updated 19 April 2020, cited 6 May 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news‐room/commentaries/detail/the‐use‐of‐non‐steroidal‐anti‐inflammatory‐drugs‐(nsaids)‐in‐patients‐with‐covid‐19.

- 11. Lim VW, Tudor Car L, Leo YS, Chen MI, Young B. Passive immune therapy and other immunomodulatory agents for the treatment of severe influenza: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2020; 14: 226–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y et al Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1708–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen G, Wu D, Guo W et al Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest 2020; 130: 2620–2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y et al Pathological findings of COVID‐19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: 420–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P et al Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID‐19. Lancet 2020; 395: 1417–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee SM, Cheung CY, Nicholls JM et al Hyperinduction of cyclooxygenase‐2‐mediated proinflammatory cascade: a mechanism for the pathogenesis of avian influenza H5N1 infection. J Infect Dis 2008; 198: 525–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arabi YM, Fowler R, Hayden FG. Critical care management of adults with community‐acquired severe respiratory viral infection. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 315–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee SM, Gai WW, Cheung TK, Peiris JS. Antiviral effect of a selective COX‐2 inhibitor on H5N1 infection in vitro . Antiviral Res 2011; 91: 330–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zheng BJ, Chan KW, Lin YP et al Delayed antiviral plus immunomodulator treatment still reduces mortality in mice infected by high inoculum of influenza A/H5N1 virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 8091–8096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Theodoridou A, Gika H, Diza E, Garyfallos A, Settas L. In vivo study of pro‐inflammatory cytokine changes in serum and synovial fluid during treatment with celecoxib and etoricoxib and correlation with VAS pain change and synovial membrane penetration index in patients with inflammatory arthritis. Mediterr J Rheumatol 2017; 28: 33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang Z, Ma X, Jia X et al Prevention of severe acute pancreatitis with cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitors: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 115: 473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Darnell ME, Taylor DR. Evaluation of inactivation methods for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in noncellular blood products. Transfusion 2006; 46: 1770–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]