Abstract

Background

Emergency department (ED) physicians and nurses frequently interact with emotionally evocative patients, which can impact clinical decision-making and behaviour. This study introduces well-established methods from social psychology to investigate ED providers’ reported emotional experiences and engagement in their own recent patient encounters, as well as perceived effects of emotion on patient care.

Methods

Ninety-four experienced ED providers (50 physicians and 44 nurses) vividly recalled and wrote about three recent patient encounters (qualitative data): one that elicited anger/frustration/irritation (angry encounter), one that elicited happiness/satisfaction/appreciation (positive encounter), and one with a patient with a mental health condition (mental health encounter). Providers rated their emotions and engagement in each encounter (quantitative data), and reported their perception of whether and how their emotions impacted their clinical decision-making and behaviour (qualitative data).

Results

Providers generated 282 encounter descriptions. Emotions reported in angry and mental health encounters were remarkably similar, highly negative, and associated with reports of low provider engagement compared with positive encounters. Providers reported their emotions influenced their clinical decision-making and behaviour most frequently in angry encounters, followed by mental health and then positive encounters. Emotions in angry and mental health encounters were associated with increased perceptions of patient safety risks; emotions in positive encounters were associated with perceptions of higher quality care.

Conclusions

Positive and negative emotions can influence clinical decision-making and impact patient safety. Findings underscore the need for (1) education and training initiatives to promote awareness of emotional influences and to consider strategies for managing these influences, and (2) a comprehensive research agenda to facilitate discovery of evidence-based interventions to mitigate emotion-induced patient safety risks. The current work lays the foundation for testing novel interventions.

INTRODUCTION

Despite widespread awareness that patients can elicit significant emotions in healthcare providers,1–4 and that providers’ emotions may play an important role in patient safety,1, 4–9 the role of emotions remains a rarely explored ‘blind spot’.5, 6, 10 Yet a substantial body of research in social cognitive and affective science demonstrates that emotions such as anger and happiness reliably and profoundly influence how people think,11–15 including the extent to which individuals process information in a heuristic, abstract, and superficial manner versus a more careful, detailed, and analytical manner (ie, system 1 vs system 216). This can have important implications for clinical decision-making and patient safety.6, 7, 17

A small body of literature has identified characteristics of ‘difficult patients’ (eg, demanding)18, 19 and suggests that they may elicit negative emotions in providers,1–3, 20 which may reduce diagnostic accuracy among medical residents.21, 22 While two recent vignette studies21, 22 found that describing a patient as ‘difficult’ reduced diagnostic accuracy, it is unclear whether this was due to negative emotions. Such descriptions might have activated stereotypes (ie, beliefs) about a patient rather than triggering ‘felt’ emotions. In contrast to beliefs, emotions are psychological states that include subjective experience (ie, feelings) and may also include expressive behaviour and physiological reactions.11, 23, 24 Given this, interventions to reduce adverse influences of emotions on clinical decision-making and behaviour will necessarily be different than those needed to combat negative beliefs about a patient.6

Using a valid, reliable, and commonly used emotion elicitation method (ie, vivid autobiographical recall) from psychological research,25, 26 the current research systematically assessed healthcare providers’ reported emotions in response to their own recent patient encounters. Given that diagnostic errors, patient safety events, and emotions are particularly prevalent in emergency medicine4, 27–29 due to unique challenges in the emergency department (ED; eg, unpredictability, stress, overcrowding, interruptions30), we conducted our investigation in this context.

In addition to focusing on patients who trigger anger or frustration, we examined two patient populations that are rarely studied in patient safety research: patients who elicit positive emotions and patients with mental health conditions. This latter population is particularly vulnerable. That is, these patients are considered ‘difficult’,18, 19 are subject to considerable stigma in the ED31 and elsewhere,32, 33 suffer a broad range of healthcare disparities,34–37 are at increased risk for diagnostic error,38 experience greater morbidity and mortality,39–41 and represent a sizeable and growing proportion of ED patients.42, 43

Drawing on the emotion, social cognition, and patient safety literatures, the purpose of this interdisciplinary investigation was to (1) assess the range and types of emotions ED physicians and nurses report in response to their own recent emotionally evocative patient encounters, (2) identify themes and emotional triggers in these encounters, and (3) explore providers’ perceptions of their engagement with these patients and whether and how emotions influenced their clinical reasoning and behaviour.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were recruited via invitations sent to ED physicians and nurses in the USA between August and October 2018, using hospital and other ED mailing lists. The invitation indicated that we were studying physicians’ and nurses’ experiences with different types of patients, and no information concerning our interest in emotional experiences was given. Interested providers were instructed to send a note to a university-based email address. Eligible providers were then sent an individualised, one-time-use link to complete the study and were given 2 weeks before the link expired. Near the end of this period, reminders were sent to providers who had not accessed the study, and they were offered a new link and an additional week to complete the study. In accordance with the average hourly rate for ED physicians in the USA at the time,44 physicians were compensated US$200.00 for completing the study. Nurses were compensated US$100.00.

Design

This study was hosted on the Qualtrics platform. Participants were asked to vividly recall and write about three recent patient encounters, including an angry encounter, a positive encounter, and one involving a patient with a mental health condition. Using the randomiser option in Qualtrics, physicians and nurses completed these tasks in one of two orders, with all participants describing the mental health encounter last. This study is a 3 (patient encounter type) × 2 (physician vs nurse) × 2 (patient description order) quasi-experiment, with the first factor within subjects and the second two between subjects. This quasi-experiment took place within the framework of a convergent mixed methods study, which allowed us to use qualitative data to add greater depth to our quantitative results.45 (See online supplementary figure S1 for study design and flow.)

Materials and procedure

This study consisted of two phases. In phase 1, we adapted a highly reliable and valid emotion elicitation method (vivid autobiographical memory recall) commonly used in the affect literature25, 26, 46–48 to elicit emotions. For the first two patient encounters, participants were instructed to think about their last few months working in the ED, including some of the patients they saw during that time. They were then asked to choose one patient experience that led them to feel irritated, frustrated or angry (vs happy, appreciated or pleased), and continued to make them feel this way when they thought about it now. Providers were prompted to describe the patients and their experience vividly and in detail by typing in a text box. Instructions for the third encounter were similar, except participants were instructed to describe an experience with a patient with a mental health condition. Complete instructions appear in the online supplementary material.

Following each description, participants completed emotion and engagement measures that assessed the extent to which they felt (1) angry (angry, frustrated, annoyed, irritated; Cronbach’s alpha=0.90), (2) sad (sad, down, discouraged; Cronbach’s alpha=0.71), (3) anxious (anxious, uneasy, nervous, uncertain, at ease, calm, relieved; Cronbach’s alpha=0.80), (4) fatigued (fatigued, exhausted; Cronbach’s alpha=0.86), (5) happy (satisfied, happy, pleased; Cronbach’s alpha=0.85), (6) self-assured (proud, self-assured, confident; Cronbach’s alpha=0.74) and (7) engaged (empathic, engaged, attentive; Cronbach’s alpha=0.70) during the encounter. These scale items were chosen based on findings from (1) an extensive review of emotion scales used in psychological research, and (2) a subsample of ED physicians (n=18) and nurses (n=14) who participated in a separate interview study (with LMI) in which providers described their emotions in the ED.4 Participants responded to each item using continuous unnumbered sliding scales. Based on where participants moved the slider, a value between 1.00 (not at all) and 5.00 (very much) was recorded. Mean scale scores were computed separately for each participant for each encounter.

In phase 2, which immediately followed, participants were presented with each encounter they described in phase 1 in random order. A subset of participants (77%; n=72; 42 physicians and 30 nurses) was asked, ‘Do you think the emotions that you experienced while treating this patient may have influenced your clinical reasoning and decision-making in this case?’ Participants who responded ‘yes’ or ‘uncertain’ were prompted to describe the influence. These questions were added following feedback we received after collecting data from 22 participants (8 physicians and 14 nurses). For each encounter, all participants made several judgements about the patient, and reported patient demographic information and information about the ED during the encounter. These questions, which were included for descriptive and exploratory purposes only, are reported in the online supplementary material along with relevant analyses (see tables S3–S5 and figure S2 in the online supplement). Finally, participants provided personal information (see table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Physicians | Nurses | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 50 | 44 |

| Mean age (SD) | 39.12 (6.38) | 37.82 (11.75) |

| Range (median) | 28–53 (39) | 25–64 (33) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 32 (64%) | 4 (9%) |

| Female | 18 (36%) | 40 (91%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 40 (80%) | 41 (93%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (2%) | 2 (5%) |

| Asian | 7 (14%) | - |

| More than one race | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) |

| Highest professional degree | ||

| Medical degree (physician) | 45 (90%) | - |

| Medical degree (physician) and PhD | 4 (8%) | - |

| Bachelor’s | - | 34 (77%) |

| Master’s | - | 5 (11%) |

| Associate’s (2-year degree) | - | 4 (9%) |

| Doctorate of Nursing Practice | - | 1 (2%) |

| Other | 1 (2%) | - |

| Mean years since receiving highest degree (SD) | 11.22 (6.89) | 9.72 (9.40)* |

| Range (median) | 1–26 (9) | 0–42 (6) |

| Country of medical education | ||

| USA | 49 (98%) | 44 (100%) |

| Israel | 1 (2%) | - |

| Mean years of experience since completing residency (physicians) or nursing training (SD) | 7.82 (6.26) | 12.66 (11.27) |

| Range (median) | 1–23 (5.5) | 1–42 (7.50) |

| Mean clinical hours/month (SD) | 96.49 (38.38) | 133.09 (40.76)* |

| Range (median) | 20–160 (96) | 15–250 (144) |

| Type of practice | ||

| Small private practice | 1 (2%) | - |

| Small community hospital | 11 (22%) | 19 (43%) |

| Large university hospital | 29 (58%) | 24 (55%) |

| Other | ||

| Medium community hospital | 3 (6%) | - |

| Large community hospital | 3 (6%) | 1 (2%) |

| Multiple affiliations | 3 (6%) | - |

| Academic affiliation | ||

| Non-academic | 10 (20%) | 11 (25%) |

| Academic | 37 (74%) | 33 (75%) |

| Hybrid | 3 (6%) | - |

Data missing for one participant.

Sample size

Based on an a priori power analysis using G*Power (V.3.1),49 we aimed to recruit 84 participants (42 physicians and 42 nurses) to achieve 80% power to detect differences in emotion and engagement profiles for different patient encounters and between physicians and nurses, assuming a medium effect size (f=0.25).

ANALYSIS

Quantitative data

Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS V.23.

To examine whether ED providers’ emotions varied by patient encounter and to explore whether such variation was dependent on participant profession (physician vs nurse) or encounter order, we subjected participants’ scores on the emotion and engagement scales to a three-way mixed multivariate analysis of variance with patient encounter as a within-subjects factor, and participant profession (physician vs nurse) and encounter order as between-subjects factors. As described in the online supplementary material, we also conducted quantitative linguistic text analysis to examine the emotional tone in providers’ written encounter descriptions.50–55

We applied Bonferroni correction to all pairwise comparisons to ensure the family-wise error rate did not go beyond 0.05.56 We used correlations to assess associations between continuous variables, and χ2 tests to examine differences in categorical variables.

Qualitative data

To identify main themes in (1) providers’ patient encounter descriptions and (2) providers’ perceptions of the influence of emotions on their clinical decision-making and behaviour, we employed inductive content analysis. Text responses were coded using Microsoft Excel V.16.23. The coding structure was determined via an iterative process. The original codebooks for each of the two coding tasks were developed by two undergraduate research assistants (RAs) and two research coordinators (JT and KB). All four individuals read all qualitative responses and worked collaboratively to create a codebook for each of the two coding tasks. The RAs individually coded all qualitative data and disagreements were resolved by research coordinators. Following this process, research coordinators read all open-ended descriptions a second time and worked together to refine the codebooks for greater specificity. They then individually coded approximately half of the patient encounter descriptions each and communicated as needed. They also independently coded all of the emotional influence data and discussed disagreements until they reached consensus.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Ninety-five providers (50 physicians and 45 nurses) participated, however one nurse was excluded from analysis for not describing any patient encounters, leaving a sample of 94 providers from 29 EDs. This sample includes 75% of the 127 eligible providers (66 physicians and 61 nurses) who responded to our email invitation and requested a study link. Sample characteristics appear in table 1. The gender distribution of participants is consistent with the distribution of nurses57 and ED physicians in the USA,58 and the distribution of race among our physicians is consistent with national data58; however, our nurses were disproportionately Caucasian.57

Emotion and engagement profiles

Ninety-four ED providers produced 282 patient encounter descriptions. Participants’ reports of their emotional experiences and engagement in these encounters varied depending on encounter type, F(14, 332)=40.20, p<0.001, η2p=0.63, and this effect was independent of participant profession (physician vs nurse), encounter order, and their interaction, F(14, 332)=1.57, p=0.09.

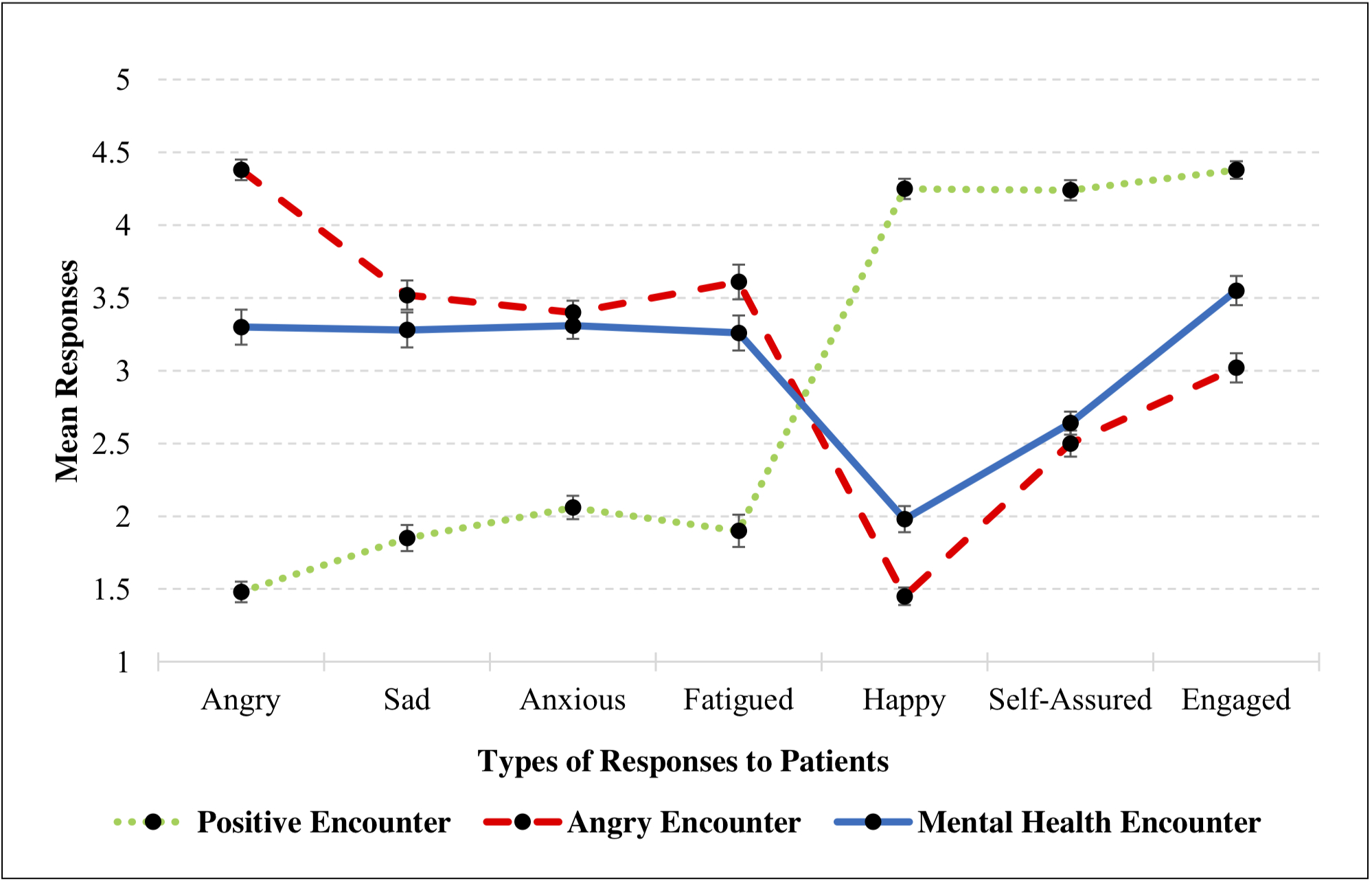

As shown in figure 1, the overall pattern of reactions to angry patients and to those with mental health conditions is similar. Providers reported feeling similarly sad (3.52 vs 3.28; p=0.18), anxious (3.40 vs 3.31; p=0.99) and low in self-assurance (2.50 vs 2.64; p=0.68). Providers also reported high levels of fatigue and anger, and low levels of happiness and engagement in response to both types of patients; however, they reported feeling more fatigue (3.61 vs 3.26; p=0.04; Cohen’s d=0.32), more anger (4.38 vs 3.30; p<0.001; Cohen’s d=1.17), less happiness (1.45 vs 1.98; p<0.001; Cohen’s d=0.72) and less engagement during angry encounters (3.02 vs 3.55; p<0.001; Cohen’s d=0.55).

Figure 1.

Providers’ emotional reactions and engagement during different patient encounters. (Note: Sliding scales range from 1.00 (not at all) to 5.00 (very much). Error bars represent plus/minus one standard error. Lines in the graph are not intended to suggest a linear relationship)

Positive encounters were marked by relatively high levels of self-reported engagement, self-assurance, and happiness, and low levels of negative emotions. To illustrate the magnitude of such differences, we collapsed providers’ reported responses in angry and mental health encounters and compared them to responses in positive encounters. Providers reported feeling significantly more engagement (4.38 vs 3.29; p<0.001; Cohen’s d=1.41), self-assurance (4.24 vs 2.57; p<0.001; Cohen’s d=2.34) and happiness (4.25 vs 1.72; p<0.001; Cohen’s d=3.51), and less anger (1.48 vs 3.84; p<0.001; Cohen’s d=−2.89), sadness (1.85 vs 3.40; p<0.001; Cohen’s d=−1.68), anxiety (2.06 vs 3.36; p<0.001; Cohen’s d=−1.73) and fatigue (1.90 vs 3.44; p<0.001; Cohen’s d=−1.46) during positive encounters compared with angry and mental health encounters. (See the online supplementary material for analyses of emotional tone in providers’ written encounter descriptions using quantitative linguistic text analysis, which converge with findings reported here.)

Relationship between reported provider engagement and emotional experiences

Reported self-assurance was associated with greater perceived engagement in positive (r=0.431; p<0.01), angry (r=0.355; p<0.01), and mental health (r=0.222; p<0.05) encounters. Reported anger was associated with lower perceived engagement in angry (r=−0.290; p<0.01) and mental health encounters (r=−0.367; p<0.01). In positive and angry encounters, reported happiness was associated with greater perceived engagement (r=0.258; p<0.05 and r=0.351; p<0.01). In angry encounters, reported anxiety and fatigue were also associated with lower perceived engagement (r=−0.241; p<0.05 and r=−0.204; p<0.05). (See online supplementary table S1 for correlations among scales.)

Patient encounters: major themes

Table 2 provides a summary of the main themes that emerged in different encounter types and their frequencies (see online supplementary table S2 for redacted examples of encounter descriptions).

Table 2.

Frequency of main themes in provider-generated descriptions of their (A) angry, (B) positive and (C) mental health encounters

|

Themes and subthemes |

Encounters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Physicians | Nurses | |

| A. Angry encounters* | |||

| Patient behaviour | |||

| Demanding, entitled, or manipulative behaviour | 50 (53%) | 27 (54%) | 23 (52%) |

| Verbal or physical abuse towards provider (actual or threatened) | 34 (36%) | 18 (36%) | 16 (36%) |

| Frequent/high emergency department utiliser | 35 (37%) | 16 (32%) | 19 (43%) |

| Unrealistic expectations (patient expected different or more care than was possible) | 23 (24%) | 17 (34%) | 6 (14%) |

| Poor self-care (patient did not manage medical condition or refused necessary treatment) | 21 (22%) | 13 (26%) | 8 (18%) |

| Issues with family members | |||

| Situations in which a family member directed hostility or anger towards the provider or patient | 15 (16%) | 6 (12%) | 9 (20%) |

| Hospital or system issues | |||

| Patient care barriers not under direct control of emergency department provider, including issues with colleagues, the emergency department system, hospital, or healthcare in general | 24 (26%) | 11 (22%) | 13 (30%) |

| Miscellaneous (content not categorised) | 6 (6%) | 3 (6%) | 3 (7%) |

| B. Positive encounters† | |||

| Relationship with patient and/or family | |||

| Gratitude expressed towards provider | 52 (55%) | 28 (56%) | 24 (54%) |

| Patient was cooperative, positive, or understanding | 19 (20%) | 15 (30%) | 4 (9%) |

| Other meaningful connection with patient | 8 (8%) | 2 (4%) | 6 (14%) |

| Success with patient care | |||

| ’Made a difference’ or advocated for patient | 37 (39%) | 18 (36%) | 19 (42%) |

| Felt proud of own abilities | 13 (14%) | 9 (18%) | 4 (9%) |

| Felt proud of team/emergency department | 7 (7%) | 4 (8%) | 3 (7%) |

| Miscellaneous (content not categorised) | 4 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (7%) |

| C. Mental health encounters‡ | |||

| Patient behaviour | |||

| Demanding, entitled, or manipulative behaviour | 49 (52%) | 19 (38%) | 30 (68%) |

| Verbal or physical abuse towards provider (actual or threatened) | 30 (32%) | 10 (20%) | 20 (45%) |

| Frequent/high emergency department utiliser | 33 (35%) | 17 (34%) | 16 (36%) |

| Poor self-care (patient did not manage medical condition or refused necessary treatment) | 16 (17%) | 8 (16%) | 8 (18%) |

| Calm, pleasant, thankful | 22 (23%) | 13 (26%) | 9 (20%) |

| Issues with family members | |||

| Situations in which a family member directed hostility or anger towards the provider or patient | 6 (6%) | 6 (12%) | 0 (0%) |

| Situations in which provider experienced sadness for a patient’s family member | 12 (13%) | 9 (18%) | 3 (7%) |

| Hospital or system issues | |||

| Patient care barriers not under direct control of emergency department provider, including issues with colleagues, the emergency department system, hospital, or healthcare in general | 36 (38%) | 21 (42%) | 15 (34%) |

| Provider emotions | |||

| Anger, frustration, irritation | 55 (59%) | 25 (50%) | 30 (68%) |

| Sadness, helplessness, empathy | 33 (35%) | 19 (38%) | 14 (32%) |

| Fear, anxiety | 12 (13%) | 5 (10%) | 7 (16%) |

| Positive emotions (appreciation, gratitude) | 8 (9%) | 3 (6%) | 5 (11%) |

| Indifference or no emotion mentioned | 12 (13%) | 8 (16%) | 4 (9%) |

| Miscellaneous (content not categorised) | 18 (19%) | 9 (18%) | 9 (20%) |

n=94 (50 physicians, 44 nurses).

Seventy-two stories (77%) were coded into two or more categories.

Forty stories (43%) were coded into two or more categories.

Ninety-three stories (99%) were coded into two or more categories.

The most prominent theme involved healthcare providers’ perceptions of patient behaviours, which differed markedly depending on encounter type. For positive encounters, the majority of encounters included gratitude from patients, whereas in angry encounters, the majority included behaviours that providers perceived to be demanding, entitled, or manipulative (53%; n=50), with a large percentage involving perceived verbal or physical abuse (36%; n=34), frequent/high utilisers (37%; n=35), and unrealistic patient expectations (24%; n=23). In mental health encounters, behaviours that providers perceived to be demanding, entitled, or manipulative similarly emerged in 52% of encounters (n=49), with a sizeable proportion involving perceived verbal or physical abuse (32%; n=30). Despite the general negativity in mental health encounters, a small proportion (23%; n=22) included patient behaviours perceived to be positive. Notably, hospital and system issues emerged as a theme most frequently in mental health (38%; n=36) and angry (26%; n=24) encounters, but not in positive encounters.

Given that somewhat more emotionally mixed themes emerged in mental health encounters, we examined provider emotions in these encounters. As shown in table 2, the most frequent emotion was anger (59%; n=55), followed by sadness, helplessness and empathy (35%; n=33), and fear/anxiety (13%; n=12). Positive emotions emerged in only 9% (n=8) of these encounters.

Emotional influences on clinical reasoning and decision-making

A majority of participants who completed the emotion influence questions (75%; n=54) perceived that their emotions influenced their clinical decision-making in at least one encounter, with this increasing to 82% (n=59) when including those who indicated uncertainty in at least one case. Participants were most likely to endorse (or indicate uncertainty) that emotions influenced them in angry encounters (63%; n=45), followed by mental health (47%; n=34), and positive encounters (39%; n=28) (p=0.02; χ2 test). No differences emerged between physicians and nurses, all p>0.33.

Themes that emerged from qualitative analysis of providers’ reports of how their emotions influenced them, along with representative quotes from providers, appear in tables 3–5. These data demonstrate that emotions experienced in angry encounters were associated with reports of detrimental behaviours that likely reduced quality of care (table 3). In contrast, emotions experienced in positive encounters led providers to report behaviours that likely resulted in better care and possibly less error (table 4). Emotions experienced in mental health encounters resulted in providers reporting behaviours that likely had both detrimental and beneficial effects (table 5), depending on specific cases and individual providers.

Table 3.

Self-reported impact of emotions in angry encounters and representative quotes (for participants who indicated their emotions influenced their clinical reasoning and decision-making in their angry encounter)*

| Angry encounters (n=38; 24 physicians, 14 nurses)† | ||

|---|---|---|

| Detrimental effects | 35 (92%) | |

| Failed to provide best possible care | 25 (66%) | |

| Delayed or failed to provide necessary exam or treatment | ‘It’s possible that I did not obtain a full history and did not conduct a full physical exam on the patient.’ (45, physician) | 10 (26%) |

| ‘I don’t do as thorough as an assessment and don’t listen as much because of frustration.’ (139, nurse) | ||

| Acted less professionally or compassionately | ‘If you get fired up about a patient, it becomes hard to really put yourself in their shoes and see what they want/need.’ (50, physician) | 8 (21%) |

| ‘… I do feel that because of his attitude and his sex offender status, I did not feel any level of empathy for him whatsoever. I continued to do my job and care for this patient and provide for him anything medically needed, but I did not go above and beyond to anticipate any needs he may have, or out of my way to provide for him the way I would with any other patient.’ (130, nurse) | ||

| Premature closure | ‘I probably prematurely closed my thoughts to them having anything bad.’ (20, physician) | 5 (13%) |

| Failed to address non-emergent concerns | ‘I was ultimately able to provide adequate care, but certainly not superlative care in addressing not only the somatic complaints but the bigger picture concerns for substance abuse and unaddressed personality disorder.’ (38, physician) | 4 (11%) |

| ‘When a patient becomes verbally abusive and manipulative I tend to not go any extra length to provide them with extra services, consults etc.’ (39, physician) | ||

| Provided unnecessary treatment | ‘I felt a bit nervous about his attitude and unreasonable expectations, which may have led me to overtreat (prescribe an antibiotic that maybe wasn’t indicated).’ (21, physician) | 4 (11%) |

| Spent less time with patient | ‘I was tired and rushed that day, so I did not spend as much time with the patient as I should have.’ (16, physician) | 4 (11%) |

| Less focused/engaged during patient care | ‘…When he was panicked and screaming despite anesthesia, my priority was on finishing as quickly as possible rather than on excellent wound edge approximation.’ (26, physician) ‘As I was getting more frustrated and stressed, I was becoming curt with my patients and families and also less focused and efficient.’ (120, nurse) | 3 (8%) |

| General negative impact on providers’ and others’ mood | 22 (58%) | |

| ‘I was overcome with anger and didn’t even want the patient to be seen at that point…’ (126, nurse) | ||

| ‘…The art of the management in this case was all about managing patient (and family) expectations. I think my brusque behavior may have irritated the father, but more impactful, it impacted the young nurse who then revved up the father and the patient.’ (35, physician) | ||

| Miscellaneous (does not fit in any categories) | 3 (8%) | |

Codes are not mutually exclusive; 47% of the responses were coded into two or more categories. Percentages that are highlighted reflect the percentage of participants whose responses were coded in at least one category within the highlighted theme or subtheme. Percentages that appear below these reflect the percentage of participants whose responses were coded for that specific category.

Seven participants responded that their emotions may have influenced their decision-making but did not include a free-text response.

Table 5.

Self-reported impact of emotions in mental health encounters and representative quotes (for participants who indicated their emotions influenced their clinical reasoning and decision-making in their mental health encounter)*

| Mental health encounters (n=34; 20 physicians, 14 nurses)† | ||

|---|---|---|

| Detrimental effects | 25 (74%) | |

| Failed to provide best possible care | 11 (32%) | |

| Acted less professionally or compassionately | ‘I felt frustrated and not empathetic towards the patient. I could have verbally de-escalated sooner and not ignored the patient to the point where she got angry.’ (16, physician) | 4 (12%) |

| Spent less time with patient | ‘I was scared to go in the room and only went in when I needed to. I did not talk with her as much as I would have other patients.’ (123, nurse) | 4 (12%) |

| Acted on bias | ‘I was biased against finding true physical illness due to the vagueness of complaints and overlay of multiple diagnosis suggesting mental health component to presentation.’ (30, physician) | 3 (9%) |

| Provided unnecessary treatment | ‘The frustration of the nursing staff may have made me more likely to give higher doses of sedating meds than I normally would.’ (12, physician) | 2 (6%) |

| ‘I feel that because I don’t have the time in a busy ED [Emergency Department] filled with “sick” medical patients to be constantly redirecting and talking to mental health patients, I opt for physical and chemical restraints more often than I should.’ (140, nurse) | ||

| Delayed or failed to provide necessary exam or treatment | ‘I was definitely swayed by the report from nursing that the patient had been difficult to deal with earlier in the day- otherwise I would have given him Narcan [naloxone] right away…’ (27, physician) | 2 (6%) |

| Premature closure | ‘I think when I became so angry over how the patient and family treated me that my better judgement of just agreeing with the doctor to discharge the patient to home definitely took over.’ (136, nurse) | 2 (6%) |

| General negative impact on provider’s mood | 20 (59%) | |

| ‘I was fed up with her, and I think she’s ridiculous the way she acts and needs real coping skills.’ (139, nurse) | ||

| ‘The frustration and exhausted feeling certainly unincentivized me to provide best care possible. We need to prioritize the time and effort [with] limited time in the ED [Emergency Department]. The emotion often is a variable that makes some contributions to the prioritization.’ (37, physician) | ||

| Beneficial effects | 18 (53%) | |

| Provided best possible care | 18 (53%) | |

| Acted with empathy, patience, and understanding | ‘Perhaps being somewhat afraid when entering the room made me calmer and attempt to be more patient in an attempt not to upset or anger her, knowing she had a history of violent tendencies.’ (119, nurse) | 13 (38%) |

| ‘Understanding her underlying mental illness made me more patient and understanding of her, tried to listen instead of just order tests on her.’ (21, physician) | ||

| Advocated for patient or provided extra care | ‘I went out of my way to take care of his emotional/physical needs. I paid attention to his outbursts I sought him out to help him.’ (128, nurse) | 9 (27%) |

| ‘I think some of the empathy I felt for her helped me to provide better care for her and motivated me to go the extra mile to try and make her ED [Emergency Department] stay better (eg, contacting social work etc.) But it was also the right thing to do.’ (48, physician) | ||

| Spent more time with patient | ‘I was able to be mindful and conscientious, taking care to note his wounds and do a thorough exam so he would get proper care further down in his evaluation…’ (133, nurse) | 5 (15%) |

| Miscellaneous (does not fit in any categories) | 2 (6%) | |

Codes are not mutually exclusive; 62% of the responses were coded into two or more categories. Percentages that are highlighted reflect the percentage of participants whose responses were coded in at least one category within the highlighted theme or subtheme. Percentages that appear below these reflect the percentage of participants whose responses were coded for that specific category.

All participant who indicated that their emotions may have influenced their decision-making included a free-text response.

Table 4.

Self-reported impact of emotions in positive encounters and representative quotes (for participants who indicated their emotions influenced their clinical reasoning and decision-making in their positive encounter)*

| Positive encounters (n=25; 13 physicians, 12 nurses)† | ||

|---|---|---|

| Beneficial effects | 20 (80%) | |

| Provided best possible care | 20 (80%) | |

| More focused/engaged during patient care | ‘More cognizant of medical complexities surrounding patient, as well as psychosocial issues.’ (11, physician) | 8 (32%) |

| Provided extra testing, consultation or treatment | ‘In that the patient was a very kind, articulate person I may have been more motivated to go the extra mile to make the correct diagnosis.’ (12, physician) | 7 (28%) |

| ‘I feel like I could do more to help the patient instead of [the] minimum required.’ (141, nurse) | ||

| Advocated for patient | ‘I think my gut feeling about the case allowed me to advocate harder for the patient and I am glad it did.’ (134, nurse) | 4 (16%) |

| Positively impacted patient’s mood | ‘My emotions helped calm the patient…’ (23, physician) | 3 (12%) |

| Spent more time with patient | ‘I’m not certain that the patient having a positive influence on me would have altered my clinical decision making, however, it made me more likely to respond to her positively. Since she was so pleasant and appreciative of everything I did for her I was happy to enter the room to help her.’ (119, nurse) | 3 (12%) |

| Expedited patient care | ‘I liked the patient and tried to expedite his care since he had been so patient.’ (25, physician) | 2 (8%) |

| Miscellaneous (does not fit in any categories) | 5 (20%) | |

Codes are not mutually exclusive; 28% of the responses were coded into two or more categories. Percentages that are highlighted reflect the percentage of participants whose responses were coded in at least one category within the highlighted theme or subtheme. Percentages that appear below these reflect the percentage of participants whose responses were coded for that specific category.

Three participants responded that their emotions may have influenced their decision-making but did not include a free-text response.

DISCUSSION

Our findings document the broad range of emotions that ED providers reported experiencing during their own recent patient encounters, including those that elicited positive emotions, negative emotions, and involved patients with mental health conditions. The emotion profiles demonstrate that providers experience a mix of discrete emotions—a finding that parallels those in the emotion literature.59, 60 Notably, providers’ emotion profiles in angry and mental health encounters are strikingly similar, reflecting high levels of negative emotion.

Providers also reported significantly lower engagement in their recent encounters with patients who elicited anger or had a mental health condition compared with encounters with patients who elicited positive emotions. Further, a large majority of providers reported that their emotions influenced their clinical decision-making and behaviour in at least one encounter. Encounters that elicited anger resulted in the lowest reported quality of care. This finding, coupled with research demonstrating that anger can trigger superficial and hasty information processing (eg, stereotype use61–63), further highlights the importance of investigating the effects of frustration and anger on providers’ clinical decision-making.

Patients with mental illness are a particularly vulnerable population who experience significant healthcare disparities,34–37 contributing to a mortality gap of 15–20 years between those with and without mental illnesses.39, 40 While patients with mental health conditions were found to elicit strong negative emotions, which can adversely influence providers and increase risks to patients, we also uncovered evidence of positive influences among a subset of providers. These providers reported greater empathy, spending more time with these patients, and advocating for them. Further, providers who reported greater self-assurance in mental health encounters also reported greater engagement with these patients. Together, these findings suggest that strategies that cultivate greater empathy and self-assurance among providers may hold promise for improving care for this vulnerable population.

Patients who elicit positive emotions have been a somewhat neglected subject of inquiry. Providers reported being more engaged with and providing what they perceived to be higher quality care to these patients, a finding consistent with research demonstrating that positive affect can facilitate flexible and integrative processing.64, 65 In vignette studies, for example, positive affect led medical students to identify lung cancer in a patient more quickly,66 and residents to consider the correct diagnosis for a patient with liver disease sooner.67 Importantly, although positive emotions may improve patient care and safety, this may not always be the case. Positive feelings towards patients may lead providers to overtest and overtreat patients, which could expose patients to unnecessary risks. Alternatively, positive emotions may reduce a provider’s belief that a patient has a serious illness, which may result in adverse outcomes. Consistent with this possibility, research demonstrates that positive emotions are associated with predictions of positive (non-serious) outcomes.68 Future work is needed to articulate the conditions in which positive emotions are helpful versus harmful to clinical decision-making.

Using different research methods and samples of ED providers, these results converge with those from a recent large-scale qualitative interview-based investigation of physicians’ and nurses’ emotional experiences in the ED.4 Both studies reveal that providers perceive negative emotions to influence patient care both when discussing this issue in general4 and when reflecting on their own specific patient encounters. Although many providers in the interview study reported actively employing strategies to reduce the likelihood that their emotions would adversely impact clinical decision-making and patient care, results from the current study suggest that such efforts are not always successful.

In providing additional evidence that emotions can and do influence healthcare providers’ clinical reasoning and behaviour,6–9 the current findings underscore the urgency for additional education, training, and interventions to reduce adverse influences. Given that our sample consisted of experienced ED physicians and nurses, our results demonstrate that the problems of emotional influences on clinical reasoning and behaviour are not necessarily concentrated among trainees, but are more widespread. This is of concern, as experienced providers often serve in teaching and training roles and may unknowingly transmit their own emotional biases to trainees. More generally, efforts to further build emotional intelligence skills among healthcare providers will serve to increase awareness of emotions and promote effective emotion regulation strategies, and should be more fully integrated into clinical training and education, as suggested by others.4–6, 8, 9

At least two cognitive interventions might be considered for reducing adverse effects of emotion on healthcare providers. The first includes changing emotional experiences (via specific emotion regulation strategies); the second involves changing the effects of emotions on clinical decision-making. Research demonstrates that cognitive reappraisal—thinking about different aspects of an emotionally evocative situation—can effectively change one’s emotions.69–72 For example, rather than focusing on frustrating aspects of an encounter with an intoxicated patient, providers may direct their thoughts to other aspects of the situation, such as staff who are helping to care for the patient. By changing one’s focus of attention in this way, emotions change, and changes to clinical decision-making should follow (ie, reducing or eliminating anger should reduce or eliminate the deleterious effects of anger).

Another cognitive intervention that is well supported by social psychological research focuses on changing the effects of emotion, rather than actual emotional experience. That is, simply changing what an emotion is about changes the effects of those feelings on judgements and information processing.13, 46, 73–78 For example, if a clinician attributes their frustration during an encounter with an intoxicated patient to something external to the patient (eg, lack of funding for community-based detox programmes), those feelings should no longer influence clinical decision-making for that patient. Thus, the simple act of attributing one’s feelings to something other than the task at hand changes the relevance of those feelings to the task, and thereby changes their influence on the task.

Although research is needed to determine the efficacy of cognitive interventions in clinical contexts, the current investigation provides methodological and theoretical advances to the study of emotional influences on clinical decision-making. To assess the causal impact of both emotions and cognitive interventions, it is essential to have methodological tools that allow researchers to conduct randomised controlled experiments in which emotions can be elicited and effects of cognitive interventions can be studied. By adopting approaches that have long been central in social cognitive and affective science, the current study provides a means to do so and lays the foundation for a more comprehensive and systematic investigation of the role of emotions in patient safety.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we asked providers to vividly recall and describe specific patient encounters and then report their emotions and engagement during those encounters. Ideally, emotions would be measured during encounters; however, this presents practical problems given the high patient volume in many EDs and the possibility that such assessments could distract providers and adversely affect patients. Although emotions elicited during our experimental task are not identical to those that were experienced during the actual patient encounters recalled, considerable evidence (including a meta-analysis of 136 studies25) supports vivid autobiographical recall as a means to re-elicit emotions representative of those experienced during an earlier event.25, 26 Moreover, a meta-analysis of 162 neuroimaging studies found that emotions experienced while recalling a past event and those experienced during an ongoing event activate the same cortical and subcortical brain regions, suggesting both share the same brain mechanisms.79–81 Thus, this method represents one effective way to capture emotional experiences, yet it produces less intense emotions than those experienced at the time of an event and is subject to recall biases.

Second, by focusing on emotional experiences in the context of recent patient encounters, this study did not capture the complexity of clinical practice. As a recent qualitative study found, providers can experience a wide array of emotions from many sources (eg, patients, hospital and system factors) during clinical practice4 and these emotions change over time. As noted earlier, this can have beneficial effects, particularly if emotions shift away from those that can adversely impact clinical decision-making. This study was not designed to assess this, but future research is encouraged.

Third, this investigation lacks objective measures of providers’ actual patient care and relied on self-reported care as a proxy. As with all self-report data, these data are potentially subject to recall biases and self-presentation concerns; thus, it is possible that self-reported care may not map onto actual care provided. However, it is more likely that some providers may have altered responses to appear more socially desirable. To the extent that this occurred, our findings may underestimate the influence of providers’ negative emotions on patients, and may overestimate the influence of providers’ positive emotions on patients.

Finally, our use of a convenience sample may reduce the generalisability of our findings. However, in contrast to much prior research that has relied on residents and medical students,82 we purposefully focused on experienced ED providers. Such providers have a broader range of patient experiences, and understanding these experiences is particularly important as researchers move forward to design and test interventions to reduce adverse impacts of emotions on patient safety.

CONCLUSION

The current study sheds light on a long-neglected ‘blind spot’ in the patient safety literature.5, 6, 10 The findings demonstrate the ubiquity and variety of emotions experienced by healthcare providers during different patient encounters, and bring much-needed attention to the possible effects of these emotions on clinical decision-making, engagement, and patient care. These findings underscore the need for education and training initiatives to promote awareness of emotional influences and to consider strategies to combat adverse effects. Importantly, the development of evidence-based interventions to mitigate emotion-induced risks to patients will require a systematic and sustained programme of research. By introducing well-established methods from social psychology, the current work paves the way for developing and testing novel interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Pat Croskerry and Mark L Graber for their valuable feedback and contributions to this manuscript during the review process. We also thank Ezekiel Kimball for providing helpful feedback on the qualitative aspects of this research, and Hannah Chimowitz and Nathan Huff for thoughtful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Funding This project was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ; grant number R01HS025752), US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) awarded to LMI.

Footnotes

Competing interests None declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer The authors are solely responsible for this document’s contents, findings and conclusions, which do not necessarily represent the views of the AHRQ. Readers should not interpret any statement in this report as an official position of AHRQ or of HHS.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Ethics approval The Institutional Review Board at the University of Massachusetts Amherst approved this study (protocol number 2016–3291).

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement No data are available. Data generated for this study include confidential and sensitive information in the form of written patient encounter descriptions and reports of clinical behaviours. These data are not available for sharing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 1978;298:883–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith RC, Zimny GH. Physicians’ Emotional Reactions to Patients. Psychosomatics 1988;29:392–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vilela da Silva J, da Silva JV, Carvalho I. Physicians experiencing intense emotions while seeing their patients: what happens? Perm J 2016;20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isbell LM, Boudreaux ED, Chimowitz H, et al. What do emergency department physicians and nurses feel? A qualitative study of emotional triggers, regulation strategies, and effects on patient care. BMJ Qual Saf 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Croskerry P, Abbass AA, Wu AW. How doctors feel: affective issues in patients’ safety. The Lancet 2008;372:1205–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croskerry P, Abbass A, Wu AW. Emotional influences in patient safety. J Patient Saf 2010;6:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LeBlanc VR, McConnell MM, Monteiro SD. Predictable chaos: a review of the effects of emotions on attention, memory and decision making. Adv Health Sci Educ 2015;20:265–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heyhoe J, Birks Y, Harrison R, et al. The role of emotion in patient safety: are we brave enough to scratch beneath the surface? J R Soc Med 2016;109:52–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozlowski D, Hutchinson M, Hurley J, et al. The role of emotion in clinical decision making: an integrative literature review. BMC Med Educ 2017;17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institute of Medicine,. National academies of sciences E and medicine. improving diagnosis in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huntsinger JR, Isbell LM, Clore GL. The affective control of thought: malleable, not fixed. Psychol Rev 2014;121:600–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isbell LM, Lair EC, Rovenpor DR. The impact of affect on Out-Group judgments depends on dominant information-processing styles: evidence from incidental and integral affect paradigms. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2016;42:485–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isbell LM, Lair EC. Moods, emotions, and evaluations as information. Oxf Handb Soc Cogn 2013:435–62. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ottati VC, Isbell LM. Effects on mood during exposure to target information on subsequently reported judgments: an online model of misattribution and correction. J Pers Soc Psychol 1996;71:39–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lerner JS, Li Y, Valdesolo P, et al. Emotion and decision making. Annu Rev Psychol 2015;66:799–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahneman D. Thinking, fast and slow. New York, NY, US: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Croskerry P Ed cognition: any decision by anyone at any time. CJEM 2014;16:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficult patient encounters in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1069–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hahn SR, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, et al. The difficult patient: prevalence, psychopathology, and functional impairment. J Gen Intern Med 1996;11:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerrard TJ, Riddell JD. Difficult patients: black holes and secrets. BMJ 1988;297:530–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt HG, van Gog T, CE Schuit S, et al. Do patients’ disruptive behaviours influence the accuracy of a doctor’s diagnosis? A randomised experiment: Table 1. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mamede S, Van Gog T, Schuit SCE, et al. Why patients’ disruptive behaviours impair diagnostic reasoning: a randomised experiment. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gross JJ, Barrett LF. Emotion generation and emotion regulation: one or two depends on your point of view. Emot Rev 2011;3:8–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clore GL, RS WJ, Dienes B, et al. Affective feelings as feedback: Some cognitive consequences In: Theories of mood and cognition: A user’s guidebook. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2001: 27–62. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lench HC, Flores SA, Bench SW. Discrete emotions predict changes in cognition, judgment, experience, behavior, and physiology: a meta-analysis of experimental emotion elicitations. Psychol Bull 2011;137:834–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quigley KS, Lindquist KA, Barrett LF. Inducing and Measuring Emotion and Affect: Tips, Tricks, and Secrets In: Reis H, Judd C, eds. Handbook of research methods in personality and social psychology. New York, NY: Oxfod University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Croskerry P, Norman G. Overconfidence in clinical decision making. Am J Med 2008;121:S24–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berner ES, Graber ML. Overconfidence as a cause of diagnostic error in medicine. Am J Med 2008;121:S2–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Croskerry P The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med 2003;78:775–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Croskerry P, Sinclair D. Emergency medicine: a practice prone to error? CJEM 2001;3:271–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Nieuwenhuizen A, Henderson C, Kassam A, et al. Emergency department staff views and experiences on diagnostic overshadowing related to people with mental illness. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2013;22:255–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knaak S, Patten S, Ungar T. Mental illness stigma as a quality-of-care problem. Lancet Psychiatry 2015;2:863–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hinshaw SP, Stier A. Stigma as related to mental disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2008;4:367–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA 2000;283:506–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan G, Han X, Moore S, et al. Disparities in hospitalization for diabetes among persons with and without co-occurring mental disorders. PS 2006;57:1126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeHert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry 2011;10:52–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGinty EE, Baller J, Azrin ST, et al. Quality of medical care for persons with serious mental illness: a comprehensive review. Schizophr Res 2015;165:227–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graber MA, Bergus G, Dawson JD, et al. Effect of a patient’s psychiatric history on physicians’ estimation of probability of disease. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:204–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thornicroft G, Farrelly S, Szmukler G, et al. Clinical outcomes of joint crisis plans to reduce compulsory treatment for people with psychosis: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2013;381:1634–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenbaum S, Tiedemann A, Stanton R, et al. Implementing evidence-based physical activity interventions for people with mental illness: an Australian perspective. Australasian Psychiatry 2016;24:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaulin M, Simard M, Candas B, et al. Combined impacts of multimorbidity and mental disorders on frequent emergency department visits: a retrospective cohort study in Quebec, Canada. Can Med Assoc J 2019;191:E724–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Owens PL, Mutter R, Stocks C. Mental Health and Substance Abuse-Related Emergency Department Visits among Adults, 2007: Statistical Brief #92 In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD): : Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2010. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK52659/ [Accessed 17 Jul 2019]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss AJ, Barrett ML, Heslin KC, et al. Trends in emergency department visits involving mental and substance use disorders, 2006–2013. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaz B 2017–2018 compensation report for emergency physicians shows steady salaries. ACEP now, 2017. Available: https://www.acepnow.com/article/2017-2018-compensation-report-emergency-physicians-shows-steady-salaries/ [Accessed 22 Oct 2019].

- 45.Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwarz N, Clore GL. Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: informative and directive functions of affective states. J Pers Soc Psychol 1983;45:513–23. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barrett LF. Solving the emotion paradox: categorization and the experience of emotion. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 2006;10:20–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barrett LF. Variety is the spice of life: a psychological construction approach to understanding variability in emotion. Cogn Emot 2009;23:1284–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, et al. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 2009;41:1149–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pennebaker JW, Boyd RL, Jordan K, et al. The development and psychometric properties of LIWC2015. Austin, tx: University of Texas at Austin, 2015. Available: https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/31333 [Accessed 17 Jul 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crossley SA, Kyle K, McNamara DS. Sentiment analysis and social cognition engine (SEANCE): an automatic tool for sentiment, social cognition, and social-order analysis. Behav Res Methods 2017;49:803–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tausczik YR, Pennebaker JW. The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. J Lang Soc Psychol 2010;29:24–54. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kahn JH, Tobin RM, Massey AE, et al. Measuring emotional expression with the linguistic inquiry and word count. Am J Psychol 2007;120:263–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohn MA, Mehl MR, Pennebaker JW. Linguistic markers of psychological change surrounding September 11, 2001. Psychol Sci 2004;15:687–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chung CK, Pennebaker JW. Chapter 14: Using Computerized Text Analysis to Track Social Processes In: Holtgraves TM, ed. The Oxford Handbook of language and social psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014: 219–30. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Darlington RB, Hayes AF. Regression analysis and linear models: concepts, applications, and implementation. New York, NY: The Guilford Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 57.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Sex, race, and ethnic diversity of U.S. health occupations (2010–2012). Rockville, MD, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rayburn WF, Xierali IM, Castillo-Page L, et al. Racial and ethnic differences between Obstetrician–Gynecologists and other adult medical specialists. Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:148–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Russell JA. A circumplex model of affect. J Pers Soc Psychol 1980;39:1161–78. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Russell JA, Barrett LF. Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: dissecting the elephant. J Pers Soc Psychol 1999;76:805–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parker MT, Isbell LM. How I vote depends on how I feel: the differential impact of anger and fear on political information processing. Psychol Sci 2010;21:548–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bodenhausen GV, Sheppard LA, Kramer GP. Negative affect and social judgment: the differential impact of anger and sadness. Eur J Soc Psychol 1994;24:45–62. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Small DA, Lerner JS. Emotional policy: personal sadness and anger shape judgments about a welfare case. Polit Psychol 2008;29:149–68. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Isen AM, Daubman KA, Nowicki GP. Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. J Pers Soc Psychol 1987;52:1122–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Isen AM. Some ways in which positive affect influences decision making and problem solving In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, Barrett LF, eds. Handbook of emotions. 3rd ed. New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press, 2008: 548–73. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Isen AM, Rosenzweig AS, Young MJ. The influence of positive affect on clinical problem solving. Med Decis Making 1991;11:221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Estrada CA, Isen AM, Young MJ. Positive affect facilitates integration of information and decreases anchoring in Reasoning among physicians. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1997;72:117–35. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mayer JD, Gaschke YN, Braverman DL, et al. Mood-congruent judgment is a general effect. J Pers Soc Psychol 1992;63:119–32. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gross JJ. Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998;74:224–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: Conceptual and empirical foundations In: New York NY, ed. Handbook of emotion regulation. 2nd edn. US: Guilford Press, 2014: 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: current status and future prospects. Psychol Inq 2015;26:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sheppes G, Scheibe S, Suri G, et al. Emotion regulation choice: a conceptual framework and supporting evidence. J Exp Psychol 2014;143:163–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beukeboom CJ, Semin GR. How mood turns on language. J Exp Soc Psychol 2006;42:553–66. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gasper K Do you see what I see? affect and visual information processing. Cogn Emot 2004;18:405–21. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Isbell LM, Lair EC, Rovenpor DR. Affect-as-Information about processing styles: a cognitive malleability approach. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2013;7:93–114. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sinclair RC, Mark MM, Clore GL. Mood-Related Persuasion Depends on (Mis)Attributions. Soc Cogn 1994;12:309–26. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schwarz N Feelings as Information: Informational and Motivational Functions of Affective States In: Higgins ET, Sorrentino RM, eds. Handbook of motivation and cognition: foundations of social behavior. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press, 1990: 527–61. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Isbell LM, McCabe J, Burns KC, et al. Who am I?: the influence of affect on the working self-concept. Cogn Emot 2013;27:1073–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kober H, Barrett LF, Joseph J, et al. Functional grouping and cortical–subcortical interactions in emotion: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage 2008;42:998–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Spreng RN, Mar RA, Kim ASN. The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Cogn Neurosci 2009;21:489–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wilson-Mendenhall CD, Barrett LF, Simmons WK, et al. Grounding emotion in situated conceptualization. Neuropsychologia 2011;49:1105–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lambe KA, O’Reilly G, Kelly BD, et al. Dual-process cognitive interventions to enhance diagnostic Reasoning: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:808–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.