Abstract

Purpose of Review

Telemedicine is a rapidly growing healthcare sector that can improve access to care for underserved populations and offer flexibility and convenience to patients and clinicians alike. However, uncertainty about insurance coverage and reimbursement policies for telemedicine has historically been a major barrier to adoption, especially among physicians in private practice (the majority of practicing allergists).

Recent Findings

The COVID-19 public health emergency has highlighted the importance of telehealth as a safe and effective healthcare delivery model, with governments and payers rapidly expanding coverage and payment in an effort to ensure public access to healthcare in the midst of an infectious pandemic. This comprehensive review of updated telemedicine coverage and payment policies will include a tabular guide on how to appropriately bill and optimize reimbursement for telemedicine services.

Summary

This review of current trends in telemedicine coverage, billing, and reimbursement will outline the historical and current state of telemedicine payment policies in the USA, with special focus on recent policy changes implemented in light of COVID-19. The authors will also explore the potential future landscape of telehealth coverage and reimbursement beyond the resolution of the public health emergency.

Keywords: Telemedicine, Telehealth expansion, Payment parity, COVID-19, Telemedicine billing, Reimbursement

Introduction

Telemedicine refers to the remote evaluation and treatment of patients using telecommunications technology. Initially envisioned in the 1920s as a virtual alternative to a physician’s house call, the technology needed to practically implement telemedicine was not developed until mid-century, when NASA needed a way to provide medical care to astronauts in space. The ambitions of telemedicine returned back to earth in subsequent decades, linking hospitals to airports in the 1960’s, delivering healthcare to Indian reservations in the 1970’s, providing healthcare support to Armenia in the wake of an earthquake in the 1980’s, and being introduced by Medicare as a way to deliver medical care to underserved rural populations in the 1990’s [1, 2]. Over the next two decades, telemedicine extended its reach beyond remote and underserved patients, to include after-hours care, walk-in urgent visits, remote physiologic monitoring, chronic care management, and routine evaluation and management services for the general population.

Impact of Reimbursement Limitations on Telemedicine Accessibility and Adoption

As telemedicine in the USA was initially envisioned as a way to increase access to healthcare for underserved and remote communities, funding for telehealth pilot programs was carved out from the budgets of government entities, such as NASA, CMS, and the Indian Health Service [2]. However, as telehealth services have become more widespread in the consumer healthcare space, sustainable payment policies from public and private payers are critical to the ongoing growth and development of telemedicine. Regulatory policy, in general, tends to lag behind advancements in technological capability, and telemedicine is no exception. Payment models have not kept pace with the rapid expansion of telemedicine technology and scope, and a 2019 report from telemedicine provider American Well revealed that the top concern of clinicians pertaining to telemedicine adoption is uncertainty about reimbursement [3]. In fact, until the recent sea change in telemedicine accessibility brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine reimbursement had been hindered by geographic restrictions, narrow coverage policies, and a lack of payment parity.

Geographic Restrictions

Medicare has historically placed stringent restrictions on the geographic location of beneficiaries who wish to avail themselves of telemedicine benefits. Until March 2020, Medicare recipients of telemedicine services needed to visit an originating site to have telehealth service facilitated by an onsite healthcare professional and initiate a live audio-visual transmission between the originating site and the distant provider. Additionally, originating sites could only be located in either a country outside a Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) or in a Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) in a rural census tract [4]. By reimbursing exclusively for facilitated telehealth services in rural HPSAs, Medicare effectively excluded patients who were home-bound (due to disability or lack of transportation) or residing in urban/suburban areas from receiving telemedicine as a covered benefit.

Coverage Restrictions

In addition to geographic restrictions imposed by Medicare, commercial payers have applied coverage restrictions on telehealth services in response to concerns over the potential for overutilization, fraud, and low-quality care. For-profit health insurers have paid close attention to data showing that although the cost of an individual telehealth service is significantly lower than outpatient and emergency care, the convenience of telemedicine can lead to greater use of care and consequently higher overall health expenditure. A RAND analysis of telehealth for acute respiratory infections estimated that net annual spending on acute respiratory illness increased by $45 per telehealth user [5]. It is important to note that the increased healthcare utilization through telemedicine is not necessarily inappropriate, but rather a reflection of care that would otherwise not have been sought had telemedicine not been available. Therefore, carriers have looked for ways to encourage patients to utilize telemedicine as a substitute for more expensive face-to-face or emergency services, rather than an addition to existing service utilization.

Commercial coverage restrictions have come in two flavors: limitation of services and restriction to a narrow network of providers. Prior to the onset of the COVID-19 public health emergency, most carriers had restrictions on the types of services that could be delivered via telemedicine. For example, although coverage for follow-up evaluation and management CPT codes was available under nearly all the major commercial carriers, coverage for new patient visits, virtual check-ins, remote evaluation of digital images or video, e-visits via patient portal, and audio-only telephone care was less common [6••]. Therefore, reimbursement was available for only a limited spectrum of virtually delivered care. Some carriers have offered coverage for telemedicine services only if care is obtained through specific telemedicine companies with which the carrier has contracted. Examples include MDLive, American Well, and Teladoc, among others. Under these arrangements, patients have access to telehealth through their insurance plan (at pre-negotiated rates), but not necessarily with their own physicians. Consequently, carrier limitations to such narrow networks of telemedicine providers have limited care to urgent or semi-urgent concerns, rather than enabling patients to utilize telemedicine as a means of augmenting chronic care management or maintaining continuity of care with their established healthcare team.

Payment Restrictions

Yet another mechanism through which access to telemedicine has been indirectly limited is via the fee schedule. Prior to the emergence of COVID-19, it was not the norm for telemedicine services to be reimbursed at the same rate as the corresponding face-to-face services, except in the few states which had legislated payment parity for telehealth [7]. Consequently, there was a financial disincentive for practices to invest in the necessary technology to expand their own telehealth offerings to patients. Conversely, studies have demonstrated that implementation of parity laws is associated with increased rates of telemedicine adoption [8].

Regulatory Variability

While Medicare telehealth reimbursement rules are relatively consistent nationwide despite their stringency, coverage for commercial and Medicaid telemedicine services in the USA is determined by a variable patchwork of differing state and payer regulations. No two states are exactly alike when it comes to how telehealth services are defined and regulated. A handful of states mandate both coverage parity and payment parity, while some mandate coverage parity only and others still have no parity regulations at all [7]. Additionally, individual commercial payers can set their own policies on how to cover and reimburse telemedicine, as long as they adhere to state guidelines. For example, a telehealth service might be reimbursed with parity to face-to-face rates in Georgia, covered but reimbursed at a lower rate than an in-person visit in Colorado, but not covered at all in Illinois. This inconsistency in coverage and payment policies can lead to confusion, incorrect coding and billing, and resultant loss of revenue.

Pre-COVID-19 State of Telehealth Coverage and Reimbursement

As mentioned above, telehealth technology and interest has grown at a more rapid clip than corresponding coverage and payment policies. In fact, from the time it started covering telemedicine services in 1999, CMS did not appreciably expand the access to telehealth beyond underserved rural areas until 2020 [9]. In this section, we will discuss existing telemedicine coverage policies of Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial health insurance carriers before the onset of the COVID-19 public health emergency. A comprehensive understanding of this baseline is important because when the COVID-induced emergency expansion of telehealth expires, it is likely that coverage and reimbursement rules will revert at least partially to these policies.

Medicare

Medicare has long required that telehealth services be administered from both an originating and a distant site. The originating site (where and established patient goes to initiate the visit) must be a designated healthcare facility either outside a metropolitan service area (MSA) or in a health professional shortage area (HPSA) within a rural census tract and must be attended by a healthcare professional whose role it is to collect vital signs and facilitate the history and physical exam through a synchronous (live) audio-visual transmission. (Notable exceptions are in Alaska and Hawaii, where demonstration projects permit the use of asynchronous, or store-and-forward, audio-visual communication using modifier—GQ.) There are no geographic restrictions for the distant site provider. While a full listing of CPT codes covered for delivery via telemedicine is available at cms.gov, the most pertinent codes for allergists include established outpatient office visits (99211-99215), subsequent hospital care services (99231-99233), and health risk assessments (96160, 96161), which should be billed using place of service “02” to signify that the service is being delivered via telemedicine. No modifier is required. The originating site bills the facility fee using HCPCS code Q3014. It is notable that the Medicare telehealth waiver states telehealth services can only be offered to Medicare beneficiaries with whom the distant site provider (or another provider under the same practice TIN) has a preexisting relationship, defined by having furnished a service to the patient within the last 3 years. Therefore, under normal circumstances, new patient visits would not be performed via telemedicine [4].

Beginning in January 2019, CMS made movement towards expansion of remote/virtual care by initiating coverage for a set of services that are not specifically designated as “telehealth” but are nevertheless furnished remotely via communications technology. Because these services are not designated as “telehealth,” per se, the more restrictive geographic and originating site requirements are not applicable. The newly added services included brief communication technology-based service/virtual check-ins (CPT G2012), remote evaluation of pre-recorded patient information (CPT G2010), and interprofessional internet consultation (CPT 99446-99449, 99451-99452). A virtual check-in is a brief (5–10 min) audio, secure written, or video-based electronic communication between an established patient and a qualified provider (MD/DO/NP/PA), often with the intention of determining if an in-person evaluation is required. Remote evaluation of pre-recorded patient photo/video (store and forward) includes review and interpretation of the information with correspondence to the patient within 24 business hours. Of note, both the “check-in” and “remote evaluation of patient information” must not result from a service in the previous 7 days or result in a service within the next 24 h (or the next available appointment). Interprofessional internet consultations take place between qualified healthcare providers to collaborate on the care of a mutual patient via telephone or synchronous/asynchronous internet communication and should result in both a verbal and written report from the consultant to the requesting provider. The requesting provider bills 99452 (maximum once per 14 days), and the consulting or provider bills 99446–99449 or 99451 (maximum once per 7 days). Interprofessional internet consultations are not subject to the established relationship rule and can therefore be provided to new patients [10].

In 2020, Medicare added coverage for “e-visits” for established patients (no geographic restriction), which are non-face-to-face patient-initiated digital communications that require a clinical decision that otherwise typically would have been provided in the office. These evaluations are to be conducted through a secure digital communication platform, such as a patient portal. The service is billed using CPT codes 99421-99423, based on the cumulative time spent in review, evaluation, and management over a 7-day period [11].

Medicaid

Medicaid has historically had less restrictive telehealth coverage than Medicare. However, because Medicaid programs are administered by the states, rather than federally, coverage for telemedicine under Medicaid varies from state to state. All 50 states and the District of Columbia reimburse for live video visits, but only 14 state Medicaid programs reimburse for asynchronous “store and forward” technology. While most states no longer adhere to Medicare’s rural geographic requirement, originating site requirements are still the norm, and only 19 states explicitly permit the patient’s home to serve as the originating site. Of special interest to allergists, 19 jurisdictions explicitly allow schools to serve as an originating site, which has an impact on the delivery of asthma care to the pediatric population. Depending on the state, additional restrictions on telehealth services may exist, including provider type, specialty, and specific CPT codes. State-specific Medicaid telehealth guidelines can be looked up through the National Telehealth Policy Resource Center [12••].

Commercial Payers

In much the same way that Medicaid telehealth policies vary from state to state, each commercial health insurance carrier also sets its own policies for telehealth coverage and reimbursement. As long as state coverage and payment regulations are followed, individual commercial carriers have significant leeway to determine their own telehealth guidelines. Forty states and the District of Columbia currently have laws that govern private payer telehealth reimbursement. However, as of January 2020, only a handful of states mandated payment parity for telehealth services (California, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Minnesota, and New Mexico) [7]. The major commercial carriers have published policies which give general guidance for which telehealth services are considered covered benefits [13–17]. For the purposes of this discussion, the coverage policies of the following major commercial payers will be reviewed: Aetna, Blue Cross, Cigna, Humana, and United Healthcare. Although policies tend to be consistent within a larger carrier’s individual plans, it is notable that subsidiary plans and employer-funded plans may have additional restrictions placed on telemedicine coverage. The best way to determine exactly which services are covered under a patient’s plan is to perform an advance benefits verification.

Coverage for live video visits for established patients has been included as a covered benefit under all of the top 5 commercial payers, using CPT codes 99211-5 (limited to 99213-5 for some Blue Cross plans), place of service “02,” and modifier -95 (or alternatively modifier—GT for Aetna, Blue Cross, and Cigna). However, prior to the expansion of telehealth coverage during the COVID-19 PHE, only one commercial payer (United Healthcare) had provisions for new patients to receive an evaluation via telemedicine. In this case, CPT 99499 was to be billed using place of service “02” instead of the usual new patient E/M code.

Coverage for non-video and asynchronous services has not been ubiquitous. Virtual check-in (G2012) has been covered by Aetna, Cigna, Humana, and United Healthcare, but not by all BlueCross plans. Remote evaluation of recorded video/image (CPT G2010), on the other hand, has only been covered by United Healthcare. Telephone visits (CPT 99441-3, 98966-8) have been covered by Aetna and Blue Cross for commercial plan members and by Humana for its Medicare Advantage members only (99441-3). Humana’s Medicare Advantage members have also been some of the only commercial insurance beneficiaries with coverage for e-visits (CPT 99421-3).

Direct-to-Consumer (DtC)

When given the choice, most patients prefer to receive telehealth from their existing healthcare providers [18]. However, when their own physicians do not offer telehealth or telemedicine services are not a covered insurance benefit, patients may elect to pay out of pocket for the accessibility, convenience, and immediacy of receiving care via telehealth. The cost of a DtC telehealth evaluation has been falling, making it more attractive to patients, especially those with high deductible health plans. For example, the standard cost of a routine telemedicine evaluation with Teladoc is $49 [19]. Surveys of outpatients demonstrate the majority of patients are willing to bear the full cost of telehealth visits (up to $50), even if they have insurance coverage [20]. As allergy care (allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, sinusitis, asthma/bronchitis, rash) has been a particular focus of DtC telemedicine companies, there is significant potential for patients with allergies and asthma to seek care outside of the medical home. A concern about this trend is that most of the virtual allergy care through DtC telehealth platforms has been provided by non-allergists, which may have implications for adherence to evidence-based best practices [21].

Current State of Telemedicine Coverage and Reimbursement During COVID-19 Public Health Emergency

In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic threw a wrench into healthcare delivery models across the USA. Stay-at-home orders, limited availability of testing to identify asymptomatic carriers, lack of personal protective equipment for healthcare workers, and a general fear of contagion all contributed to a dramatic reduction in the number of outpatient face-to-face visits for both urgent and chronic health conditions [22••]. Recognizing that without widespread availability of safe and accessible healthcare, the COVID-19 pandemic might also bring with it a second wave of morbidity and mortality from untreated acute and chronic conditions, CMS, commercial carriers, and state governments acted with unprecedented speed to dramatically expand telemedicine access and reimbursement [23].

Coverage Parity

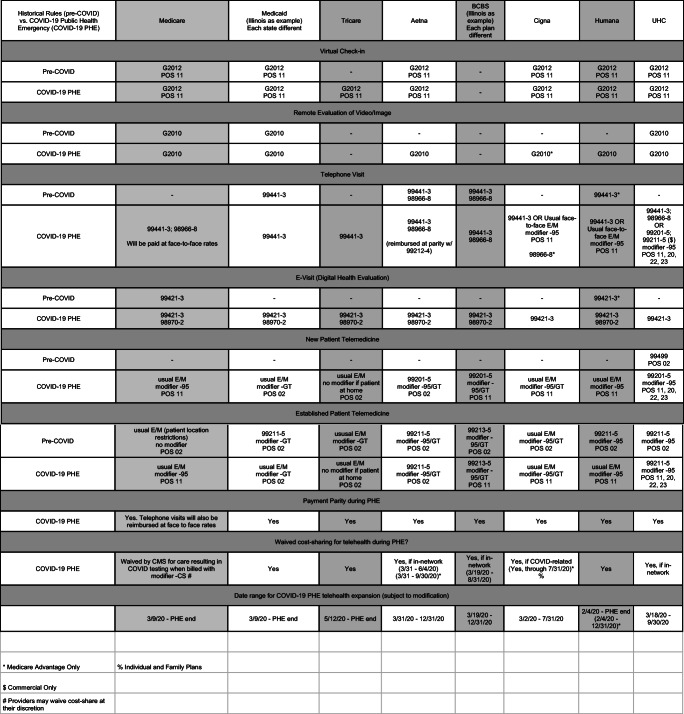

A part of the expansion of telehealth services during the COVID-19 PHE, a number of remote services which were previously non-covered by payers gained temporary coverage. The newly covered services most pertinent to allergists include evaluation and management visits for new patients (CPT 99201-5), review and evaluation of pre-recorded images/video (CPT G2010), audio-only visits via telephone (CPT 99441-3, 98966-8), and e-visits (CPT 99421-3) [24–31]. The goal of this expansion is to enable patients to access care without leaving the safety of their homes while still compensating providers for the work of managing patients remotely. Please refer to Table 1 for a summary of telemedicine billing guidance by payer, current as of the date of this publication.

Table 1.

Summary of telemedicine billing and coding guidelines by payer (pre-PHE and during PHE)

Payment Parity

Another critical element of the telehealth expansion is the implementation of payment parity. Reimbursing for telemedicine visits at the same rate as in-person visits has been instrumental in encouraging increased telemedicine adoption among providers. On March 30, 2020, CMS announced that it would allow telehealth to fulfill the requirements for a variety of inpatient and outpatient evaluation and management services and would reimburse at in-person rates [32]. Commercial carriers were encouraged, but not required, to follow CMS’s lead in this regard. Over the next few weeks, most major commercial carriers announced that they would also reimburse for synchronous video E/M visits at parity with in-person rates, provided that billing is submitted with the same place of service as an in-person visit (“11” for most outpatient allergists) and modifier -95 to designate the service as telehealth [24–28] (see table). Many states have also released emergency guidance for Medicaid plans to reimburse telehealth at parity with in-person rates [33]. Medicare and Aetna additionally have increased reimbursement for telephone visits to approximate the rates payable for in-person E/M visits. However, it is important to note that CMS will not pay rates over and above the charged rate. Therefore, if a practice’s current rate sheet has set the charge for telephone visits significantly lower than those for face-to-face visits, payment parity may not be realized for audio-only visits [30].

Regulatory Relaxation

The temporary relaxation of enforcement of certain HIPAA-compliance regulations has eased the road for practices lacking the requisite technologic infrastructure to provide telemedicine services in an end-to-end encrypted manner. This has opened the door for practices to get paid for telehealth services provided via nonpublic facing communication applications, such as Facetime, Skype, and WhatsApp [34]. However, recognition that some patients may not have access to video-enabled devices or high speed internet connections has also led some payers to either permit audio-only visits to qualify for billing as telehealth [26, 28]. While CMS has been reluctant to suspend the live video requirement for telemedicine visits, it did release guidance that reimbursement for audio-only telephone visits would be increased to approximate payment for face-to-face visits [30].

Individual states have also taken steps to remove policy barriers to telehealth utilization. Examples of actions include temporarily waiving in-state licensure requirements, prohibiting insurers from imposing prior authorization requirements on or denying medically necessary telehealth services provided by in-network providers, instituting payment parity, waiving cost-share requirements for in-network telehealth services, and suspending the requirement for a patient to have an established relationship and physical exam on file before telehealth services can be provided in the state [33]. These measures have also served to significantly expand the scope of telemedicine services that can be legally provided and compensated during the PHE.

With the understanding that it may be difficult for practices to meet elements for telemedicine billing using medical decision-making criteria, time-based billing for telemedicine has been temporary streamlined by allowing coding based on the total time spent rendering the service, instead of mandating that 50% of the total time be spent in counseling and/or coordination of care [22••].

Telemedicine Adoption

The onset of the COVID-19 public health emergency ushered in a dramatic increase in the adoption and implementation of telemedicine among healthcare practices. Healthcare providers who had previously been reluctant to implement telemedicine were forced to accelerate their timeline out of necessity. The sudden inability to provide face-to-face care to patients in need of healthcare services was the primary impetus to adopt telemedicine. However, no less important was the need to reinstate a revenue stream sufficient to cover overhead expenses and prevent medical practices from going out of business. An MGMA survey reported that private medical practices have suffered a 60% average decrease in patient volume and a 55% decrease in revenue since the beginning of the public health emergency, with 97% of surveyed practices reporting a negative financial impact from COVID-19 [35]. This reality has transformed the implementation of telemedicine from a future plan to an urgent necessity. Regulatory relaxation and enactment of parity for telehealth services, as described above, has facilitated the conversion of previously uncompensated care (telephone discussions, patient portal messaging, review of digital images, etc.) into reimbursable services. This, combined with a flurry of clarified billing guidance from payers, has been an added incentive for “telemedicine-naive” practices to begin offering virtual care to their patients.

For those practices that were already early adopters of telemedicine, the current telehealth expansion has presented an opportunity to leverage existing capabilities and be paid for virtual care to new, out-of-state, and out-of-network patients. Additionally, practices comfortable with telemedicine have been innovative in re-evaluating their current procedures to determine which existing face-to-face services might be safely converted to telehealth. A notable allergy-specific example is the remote management of anaphylaxis, with evaluation and monitoring provided via synchronous telemedicine in lieu of sending the patient to the emergency department in the midst of a pandemic [36]. The ability to be paid for these services has mobilized innovation in determining which patients are considered good candidates to access care via telemedicine.

Importance of Internal Audits

In a rapidly changing regulatory landscape, it is essential for providers of telemedicine services to stay abreast of adjustments in billing and coding rules. Incorrect billing and coding can result in denied claims or delayed and decreased payments. Over the course of the PHE, CMS, Medicaid, and commercial payers have continued to make significant changes to telemedicine billing guidance, in some cases on a daily basis. If you are still following outdated billing guidance from March, you may be leaving money on the table in July. A key example is the place of service (POS) code. Historical billing guidance for live telemedicine services is to use POS “02” to signify telehealth. However, this may be associated with a lower payment for an E/M code in a state that does not mandate payment parity, as many commercial insurers have a lower payment scale for telemedicine and Medicare reimburses at the lower facility rate for telemedicine services billed with this POS code. Updated guidance for Medicare and most commercial payers (except Aetna) is that for the duration of the COVID-19 PHE, telemedicine services should be billed using the POS that would have been used if the service was provided in person, along with modifier -95 [24–28]. For outpatient allergy practices, this is POS “11.” Doing so will ensure that the claim is paid at parity with non-facility face-to-face rates for Medicare and most commercial payers. While Humana has released guidance that resubmission of claims that were billed using POS “02” is not necessary and that payments will be adjusted to in-person rates automatically, this is not the case for all payers [27]. Therefore, practices may benefit from conducting internal audits of telemedicine claims and resubmitting any claims that were billed using outdated guidance. Please refer to Table 1 for a summary of telemedicine billing guidance by payer, current as of the date of this publication. It should be noted that because some payers have waived patient cost-share for telehealth services for the duration of the PHE, resubmission of claims may reveal that co-pays or cost-share collected from patients is no longer applicable. This may result in the need to provide refunds to patients. Other patients may be left with increased deductible or coinsurance responsibilities for telehealth when the services are paid at parity. It is in the best interest of both the patient and the practice for any such discrepancies to be handled promptly and with clear communication, to avoid confusion and frustration. The authors recommend that all patients receiving telemedicine services be advised in advance that billing and payment policies for telehealth services are currently in flux and that patient responsibility may need to be adjusted based on revised payer guidance.

Future State of Telemedicine in Allergy Care

Telemedicine was already steadily on the rise before COVID-19 made an appearance, but the public health emergency has now cemented the pivotal role of telehealth in modern healthcare delivery. Although it is unlikely that all the current measures taken to rapidly expand telehealth coverage and reimbursement will be made permanent without modification, it will also be impossible to revert fully to the status quo. For one, patients will demand continued access to telemedicine services. According to JD Power, telehealth satisfaction is among the highest out of all healthcare, insurance, and financial services [37]. Specific to allergy, surveys of recipients of pediatric tele-allergy services show that satisfaction is at least equal to, if not greater than, face-to-face care [38]. However, based on earlier analyses of the relationship between reimbursement and adoption, providers will only be willing to continue offering telemedicine services as an alternative to in-person care if they feel that the compensation is adequate for the investment of time and resources [8]. To that end, the authors anticipate that coverage and payment parity will become more widespread in an effort to encourage increased telehealth access with a patient’s existing healthcare team. However, we also expect that payers are likely to reinstate cost-sharing responsibilities or place coverage limits on the frequency of telemedicine services in order to discourage overutilization and keep healthcare expenditures in check.

Another factor which will contribute to telemedicine remaining central to American healthcare is that COVID-19 is not anticipated to be a short-term problem. The NIAID has suggested that COVID-19 is expected to become part of the infectious disease landscape, and a widely available vaccine is over a year away [39]. Until herd immunity from natural infection or vaccination controls the spread of disease, telemedicine will continue to play an important role in maintaining public health by enabling physical distancing, especially for higher risk patients with active chronic respiratory disease or immune deficiency. Remote monitoring of infected patients will be necessary to reduce morbidity and mortality from COVID-19, and remote management of conditions such as asthma will be critical to prevent the consequences of deferred chronic care management. Furthermore, the convenience and accessibility of telemedicine will be of great benefit as the economy reopens and patients (many of whom may have been required to exhaust their PTO in the early stages of quarantine) once again schedule their healthcare appointments within the confines of school/work calendars. As many of the coverage and reimbursement changes designed to increase telemedicine adoption are temporally tied to the duration of the COVID-19 public health emergency, expanded access policies for telehealth services may be a longer-term solution than initially anticipated. During this time, allergists can expect states and payers to carefully examine telehealth coverage and reimbursement as they work to develop updated policies that meet the long-term goals of patients, providers, and payers during our “new normal.”

Conclusion

Telemedicine reimbursement policies have been slow to adapt to rapid advances in technology and increased demand for the service. Stringent geographic, coverage, and payment restrictions from both public and private health insurers have been barriers to telehealth adoption among healthcare providers, including allergists. Significant variability in coverage and payment policies among states and payers has further contributed to confusion about how to obtain fair reimbursement for providing virtual care. The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has jump-started a major expansion of telemedicine coverage and reimbursement, facilitating widespread implementation of telehealth among healthcare facilities and increasing access to critical healthcare for a self-quarantining nation. Additionally, revenue generated from increased telemedicine coverage and reimbursements has kept many practices afloat during the unprecedented economic downturn. Although allergists and patients alike are looking forward to the end of the pandemic and a return to face-to-face care, it is likely that the “post-COVID” allergy practice of the future will incorporate many of the telehealth services introduced during the public health emergency. Robust advocacy on behalf of patients and practicing allergists will ensure that coverage, billing, and payment policies rise to the challenge of promoting continued innovation in telehealth delivery.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Bajowala reports that she serves on the AAAAI-ACAAI Joint Task Force on Technology and Telemedicine, the AAAAI Advocacy Committee, and the AAAAI Telemedicine Workgroup. Ms. Bansal and Mr. Milosch declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Telemedicine and Technology

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• Of major importance

- 1.Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine . The Role of Telehealth in an Evolving Health Care Environment: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bashshur R, Shannon GW. History of telemedicine: evolution, context, and transformation. Mary Ann Liebert: New Rochelle; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Telehealth Index: 2019 Physician survey. American Well 2019. https://static.americanwell.com/app/uploads/2019/04/American-Well-Telehealth-Index-2019-Physician-Survey.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 4.Telehealth services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Medicare Learning Network. 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/TelehealthSrvcsfctsht.pdf?utm_source=Telehealth+Enthusiasts&utm_campaign=2a178f351b-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2019_04_19_08_59&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_ae00b0e89a-2a178f351b-353223937. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 5.Ashwood JS, Mehrotra A, Cowling D, Uscher-Pines L. Direct-to-consumer telehealth may increase access to care but does not decrease spending. Health Aff. 2017;36(3):485–449. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.•• COVID-19: unmasking telehealth. A telemedicine workgroup report. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. Forthcoming 2020. A comprehensive overview of telemedicine implementation for allergists and immunologists, authored by the AAAAI Telemedicine Workgroup.

- 7.State telehealth laws and reimbursement policies: a comprehensive scan of the 50 states & the District of Columbia, Spring 2020. 2020. https://www.cchpca.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/CCHP_%2050_STATE_REPORT_SPRING_2020_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 8.Neufeld JD, Doarn CR, Aly R. State policies influence medicare telemedicine utilization. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(1):70–74. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2015.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Accessed 13 May 2020.

- 10.Medicare program; revisions to payment policies under the physician fee schedule and other revisions to part B for CY 2019. Department of health and human services, Centers Med Med Serv. 2018. https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2018-24170.pdf?utm_source=Telehealth+Enthusiasts&utm_campaign=bd7f7979d7-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2018_11_06_06_05&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_ae00b0e89a-bd7f7979d7-353223937. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 11.Revisions to payment policies under the Medicare physician fee schedule, quality payment program and other revisions to part B for CY 2019. Centers Med Med Serv. 2018. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/PFS-Federal-Regulation-Notices-Items/CMS-1693-F. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 12.•• Current state laws and reimbursement policy. Center for Connected Health Policy. 2020. https://www.cchpca.org/telehealth-policy/current-state-laws-and-reimbursement-policies. Accessed 15 May 2020. An up-to-date report from the nonprofit and nonpartisan National Telehealth Policy Resource Center, with state-specific telehealth regulatory information.

- 13.Start working with Aetna today. Availity. 2020. https://www.availity.com/aetnaproviders. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 14.News and updates. BlueCross BlueShield of Illinois. 2020. https://www.bcbsil.com/provider/education/news_index.html. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 15.Resources. Cigna. 2020. https://static.cigna.com/assets/chcp/resourceLibrary/resourceLibrary.html. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 16.Updated claim payment policies and two timely reminders. Humana. 2020. https://www.humana.com/provider/news/publications/humana-your-practice/online-claim-payment-policies. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 17.Telehealth and telemedicine policy, professional. United Healthcare. 2020. https://www.uhcprovider.com/content/dam/provider/docs/public/policies/comm-reimbursement/COMM-Telehealth-and-Telemedicine-Policy.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 18.Welch B, Harvey J, O’Connell N, McElligott J. Patient preferences for direct-to-consumer (DtC) telemedicine services: a nationwide survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:784. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2744-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.How much do Teladoc services cost? Teladoc. 2020. https://www.teladoc.com/how-it-works/. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 20.Donelan K, Barreto EA, Sossong S, et al. Patient and clinician experiences with telehealth for patient follow-up care. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(1):40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott T, Shih J. Direct to consumer telemedicine. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019;19(1):1. doi: 10.1007/s11882-019-0837-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Portnoy J, Waller M, Elliott T. Telemedicine in the era of COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(5):1489–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.COVID-19 telehealth coverage policies. Center for Connected Health Policy. 2020. https://www.cchpca.org/resources/covid-19-telehealth-coverage-policies. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 24.COVID-19: telemedicine FAQs. Aetna. 2020. https://www.aetna.com/health-care-professionals/provider-education-manuals/covid-faq/telemedicine.html. Accessed 10 July 2020.

- 25.Telehealth. Blue cross blue shield of Illinois. 2020. https://www.bcbsil.com/provider/providersearch.html?keyword=telehealth&x=0&y=0&state=il&portal=&collectionType=il_prod_provider. Accessed 30 June 2020.

- 26.Cigna’s response to COVID-19. Cigna. 2020. https://static.cigna.com/assets/chcp/resourceLibrary/medicalResourcesList/medicalDoingBusinessWithCigna/medicalDbwcCOVID-19.html. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- 27.Telehealth - expanding access to care. Humana. 2020. https://www.humana.com/provider/coronavirus/telemedicine. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- 28.COVID-19 telehealth services. United Healthcare. 2020. https://www.uhcprovider.com/en/resource-library/news/Novel-Coronavirus-COVID-19/covid19-telehealth-services.html. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- 29.Tricare coverage and payment for certain services in response to the COVID–19 pandemic. Department of Defense. 2020. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-05-12/pdf/2020-10042.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 30.Physicians and other clinicians: CMS flexibilities to fight COVID-19. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-19-physicians-and-practitioners.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 31.Telehealth services expansion promoted by COVID-19. Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. 2020. https://www.illinois.gov/hfs/MedicalProviders/notices/Pages/prn200320b.aspx. Accessed 13 May 2020.

- 32.Additional background: sweeping regulatory changes to help U.S. healthcare system address COVID-19 patient surge. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/additional-backgroundsweeping-regulatory-changes-help-us-healthcare-system-address-covid-19-patient. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 33.COVID-19 related state actions. Center for Connected Health Policy. 2020. https://www.cchpca.org/resources/covid-19-related-state-actions. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 34.Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. Department of Health & Human Services. 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 35.COVID-19 financial impact on medical practices. Medical Group Management Association. 2020. https://www.mgma.com/getattachment/9b8be0c2-0744-41bf-864f-04007d6adbd2/2004-G09621D-COVID-Financial-Impact-One-Pager-8-5x11-MW-2.pdf.aspx?lang=en-US&ext=.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 36.Casale T, Wang J, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. Acute at home management of anaphylaxis during the COVID-19 pandemic, J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020. ISSN 2213-2198. 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Telehealth: best consumer healthcare experience you've never tried, says J.D. Power study. J.D. Power. 2019. https://www.jdpower.com/business/press-releases/2019-us-telehealth-satisfaction-study. Accessed 15 May 2020.

- 38.Portnoy J, Taylor L. A350 telemedicine and patient satisfaction in allergy and immunology. Ann Aallergy, Asthma Immunol. 2019;123(5):S11. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.08.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Developing therapeutics and vaccines for coronaviruses. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. 2020. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/coronaviruses-therapeutics-vaccines. Accessed 15 May 2020.