Abstract

Ethnopharmacological relevance

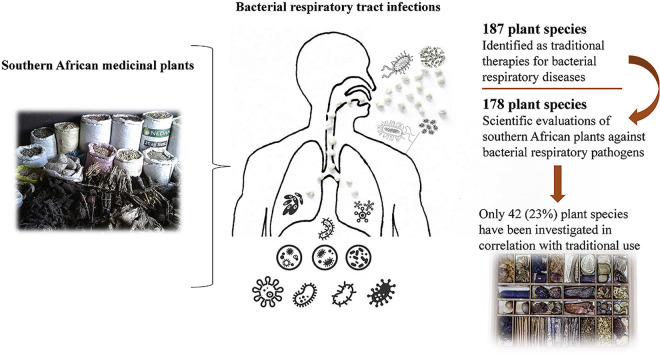

Multiple plant species were used traditionally in southern Africa to treat bacterial respiratory diseases. This review summarises this usage and highlights plant species that are yet to be verified for these activities.

Aim of the study

This manuscript reviews the traditional usage of southern African plant species to treat bacterial respiratory diseases with the aim of highlighting gaps in the literature and focusing future studies.

Materials and methods

An extensive review of ethnobotanical books, reviews and primary scientific studies was undertaken to identify southern African plants which are used in traditional southern African medicine to treat bacterial respiratory diseases. We also searched for southern African plants whose inhibitory activity against bacterial respiratory pathogens has been conmfirmed, to highlight gaps in the literature and focus future studies.

Results

One hundred and eighty-seven southern African plant species are recorded as traditional therapies for bacterial respiratory infections. Scientific evaluations of 178 plant species were recorded, although only 42 of these were selected for screening on the basis of their ethnobotanical uses. Therefore, the potential of 146 species used teraditionally to treat bacterial respiratory diseases are yet to be verified.

Conclusions

The inhibitory properties of southern African medicinal plants against bacterial respiratory pathogens is relatively poorly explored and the antibacterial activity of most plant species remains to be verified.

Keywords: Southern African plants, Tuberculosis, Diphtheria, Pertussis, Whooping cough, Pneumonia, Traditional medicine

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Four diseases account for the majority of bacterial respiratory infections globally. Of these, tuberculosis (caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis) has the greatest burden and is classified as one of the top ten causes of death globally (Floyd et al., 2018). This disease is highly contagious and is readily spread via airborne transmission. Indeed, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that more than 10 million people fell ill with tuberculosis in 2018, with 1.5 million people dying from the disease (WHO, 2019a). Of the people contracting M. tuberculosis infections, only 10% develop the active form of the disease and fall ill (Houben and Dodd, 2016). Therefore, it is estimated that a pool of 100 million new potentially infective people contracted M. tuberculosis infections in 2018. Bacterial pneumonia is also a considerable cause of mortality and morbidity. Indeed, it is classed as the second highest cause of mortality of any communicable disease (after tuberculosis), with more than 800,000 deaths estimated in 2017 (WHO, 2018). Diphtheria and pertussis caused similarly high mortality rates prior to the widespread introduction of effective vaccination (Holý et al., 2017). Vaccines have been particularly effective and the rates of infection and mortality have decreased dramatically. For example, the number of reported cases of diphtheria decreased from >1 million cases in 1980 to approximately 4500 in 2018 (WHO, 2019b; Holý et al., 2017). Similar trends for the incidence of pertussis have been reported although it still causes a considerable health burden, with 150,000 new cases and 90,000 deaths reported in 2018 (WHO, 2019c; (Holý et al., 2017). This review concentrates on the use of southern African plants to treat these four diseases due to their relevance to southern African health. Whilst other bacteria such as Legionella pneumophila (Legionaires disease) may also cause respiratory diseases, they make relatively minor contributions to southern African health (Muchesa et al., 2018) and thus are not a focus of this review.

1.1. Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is the most serious of the bacterial respiratory infections globally (Floyd et al., 2018). It is classified by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as one of the top ten causes of death globally, and the leading cause of death by a single pathogen, ranking substantially ahead of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) (WHO, 2019a). TB has a high infection rate due to its air-borne route of transmission. When an infected person coughs or sneezes (or even talks), small droplets of saliva containing the bacterium are released and dispersed into the air. If other individuals breathe in these droplets, they may also become infected. The spread from person to person is rapid and there is a high infection rate. Indeed, the WHO estimates that approximately a quarter of the world's population is infected with M. tuberculosis at any given time and thus at risk of developing TB (WHO, 2019a; Floyd et al., 2018). These high rates of infection also increase the risks of infection to non-infected members of the population.

Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, although it can also infect other parts of the body. Most infections are asymptomatic and are known as latent TB. People with latent TB do not suffer from the disease's symptoms, nor do they generally spread the disease (Furin et al., 2019). However, they have the potential to spread the bacterium if the disease progresses and therefore they constitute a substantial potential disease reservoir. However, active TB infections are substantially more frequent in immune-compromised individuals, such as people with HIV/AIDS (Pawlowski et al., 2012). When active TB develops, there is a high mortality rate, with approximately 50% of afflicted individuals dying unless they receive timely and effective medical treatment (Floyd et al., 2018).

A number of symptoms are evident in people with TB: chronic coughing with blood containing sputum, fever, night sweats and rapid weight loss (which is responsible for the historical name ‘consumption’) (Furin et al., 2019). Medical intervention for TB most frequently involves vaccination and >90% of children are vaccinated globally. The efficacy of the vaccine is low, decreasing the risk of acquiring a M. tuberculosis by only 20%. However, once an infection occurs, the vaccination decreases the chances that the infection will develop from a latent to active form of TB by 60%. If active TB develops, treatment with antibiotics for 6–9 months is often effective in curing the disease and blocking the transmission from the infected person to others (Nguyen, 2016). However, limited classes of antibiotics are effective against M. tuberculosis as the cell wall blocks cell entry for most antibiotic classes. A combination of rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol is generally used to increase the efficacy of the treatment (Furin et al., 2019). Of considerable concern, there are increasing reports of M. tuberculosis strains with resistance to these antibiotics, rendering these combinations of little use (Nguyen, 2016). Effective new antibiotic therapies are urgently required to treat these resistant strains.

1.2. Diphtheria

Diphtheria is another bacterial infection that can cause substantial mortality. Indeed, 5–10% of infections result in death, although the mortality rate can be as high as 20% in children less than 5 years of age and in adults over 40 years old (WHO, 2019b; Holý et al., 2017). Outbreaks are rare in developed countries due to medical advances, although they are more common in developing populations. Diphtheria primarily affects the upper respiratory tract, causing symptoms that range from mild to severe (Truelove et al., 2019). The disease is caused by the bacterium Cornyebacterium diphtheria and is transmitted in a similar way to TB: from person to person via air-borne pathways. Once a person breathes in the bacterium, disease progression is rapid, with symptoms usually evident within 2–5 days after exposure. The symptoms may include a sore throat, fever, chills, fatigue, cyanosis, coughs, headaches, difficulty swallowing and swollen lymph nodes, resulting in swelling of the neck. Grey or white pseudo-membrane patches may also develop in the throat of infected people, restricting the airways and causing a ‘barking’ cough similar to that seen for croup. In severe cases, myocarditis, nerve inflammation, renal disease and decreased blood clotting (due to low platelet levels) may also occur.

The widespread usage of an effective vaccine has substantially reduced the incidence of diphtheria globally (WHO, 2019b; Holý et al., 2017). This vaccine is now routinely given to children (in conjunction with whooping cough and tetanus vaccines) as a three or four dose regimen. Immunity is not life-long and repeated vaccinations are recommended every ten years after the initial vaccination. The diphtheria vaccination is generally quite effective and has greatly reduced the incidence of the disease since its widespread introduction. Indeed, the WHO estimates that approximately 4500 cases of diphtheria are now reported each year, down from >1 million cases a year prior to 1980 (WHO, 2019b; Holý et al., 2017). When C. diphtheriae infections occur (generally in non-vaccinated people in developing countries), antibiotic therapy may be effective in curing the disease and blocking its further spread. Metronidazole, erythromycin, penicillin-G, rifamin or clindamycin are most frequently used to treat diphtheria (Truelove et al., 2019). However, multi-antibiotic resistant C. diphtheriae strains are increasingly being reported (Floros et al., 2018; Mohankumar et al., 2018) and new antibiotic therapies are required.

1.3. Pertussis (whooping cough)

Pertussis (commonly known as whooping cough) is a highly contagious bacterial disease that infects large numbers of people annually despite the availability of an effective vaccine (Holý et al., 2017). Indeed, the WHO estimated that over 150,000 new cases were reported in 2018, with nearly 90,000 deaths (WHO, 2019c). However, not all cases are reported, particularly in developing countries, and it is likely that the WHO estimate substantially understates the prevalence of this disease. Indeed, other studies have estimated that there were 24.1 million pertussis cases and over 160,000 deaths of children under five years of age in 2014 (Yeung et al., 2017). Whilst these incidence rates remain unacceptably high, the introduction of a pertussis vaccine in the 1940's has resulted in dramatic reductions in regions that have introduced pertussis vaccination programs (Holý et al., 2017). For example, before the introduction of the vaccine, the incidence of pertussis in the United States of America was estimated to be approximately 180,000 annually (CDC, 2019). Following vaccination, the incidence in that country fell dramatically to an estimated 1000 new cases per year in 1976. Since that time, the incidence has risen again to nearly 19,000 in 2017.

Pertussis is caused by the bacterium Bordetella pertussis (Holý et al., 2017). It is an airborne disease and is spread in a similar manner to TB and diphtheria. Once a person is infected with the bacterium, it generally takes 6–20 days for the symptoms to become evident. Initially the symptoms are similar to a common cold, with a runny nose, fever and mild cough being common. These rapidly progress to the characteristic severe coughing fits, followed by a sudden inhalation, producing the ‘whooping’ sound that gives the disease the common name whooping cough. The disease is protracted, with the symptoms often lasting up to 10 weeks. The coughing can be so severe that it can cause subconjunctivial haemorrhages, rib fractures, hernias, urinary incontinence and vertebral artery dissection (WHO, 2019c).

Vaccination is the main form of pertussis control and is approximately 70–85% effective, dependent on the B. pertussis strain (Holý et al., 2017). However, recent genetic shifts in the bacterium have rendered some strains less susceptible to the vaccine (Mooi et al., 2014). Furthermore, immunity conferred by vaccination is not life-long and has been estimated to only last 4–12 years (Wendelboe et al., 2005). If a person contracts pertussis, macrolide antibiotics including erythromycin, clarithromycin or azithromycin are generally effective. However, macrolide resistant B. pertussis strains have been reported (Liu et al., 2018; Lönnqvist et al., 2018) rendering these antibiotics of little use. Effective new therapies are urgently required.

1.4. Bacterial pneumonia

Bacterial pneumonia is characterised by lung inflammation due to bacterial infections (Brooks, 2020). It is not a single disease and can be caused by multiple bacterial species including Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pnuemoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphyloccus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Bacterial pneumonia is a significant medical burden and causes considerable loss of life annually. Indeed, lower respiratory infections (of which bacterial pneumonia is the major mortality causing disease) are one of the highest causes of death of all communicable diseases (Brooks, 2020; WHO, 2018). The severity of bacterial pneumonia varies widely from mild to life-threatening, or even death. The severity is dependent on a number of factors including the bacterial species and strain causing the infection, the age of the infected person (children and older people tend to suffer more severe symptoms), the immunological status of the infected person, and their general health. The symptoms are generally the same irrespective of the bacterial species/strain or the age of the infected person and include chest pains, shortness of breath, frequent coughing which produces yellow or green coloured mucus, fever, lethargy and chills. In severe cases, infected individuals may develop complications including respiratory failure, sepsis, lung abscesses or empyema (accumulation of pus in the pleural cavity surrounding the lungs).

Infection with these bacteria is most frequently via similar transmission pathways as TB, diphtheria and pertussis (i.e. air-borne transmission), and is classified as community acquired pneumonia (Brooks, 2020). This accounts for the vast majority of bacterial pneumonia cases. However, hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia (HCAP) is also relatively common and occurs when a sick patient (who has a compromised immune system due to an existing medical condition) contracts an infection whilst in hospital. Ventilator-acquired pneumonia (VAP) may also occur when contaminated equipment is used to ventilate a patient. However, whilst HCAP and VAP are significant issues, air-borne transmission is the major route of transmission.

In contrast to the other bacterial respiratory diseases already discussed, there are few effective vaccines to prevent bacterial pneumoniae, although vaccines are available against Pneumonococcal spp. (Brooks, 2020). Treatment for bacterial pneumonia is generally reactive and is reliant on the use of antibiotics to kill the infective bacteria. The specific antibiotic(s) used are dependent on the infective bacterium. Antibiotic therapy is generally effective against most infective strains, although resistance of bacterial pneumonia strains to antibiotics is becoming relatively common and antibiotic therapies are increasingly failing (Peyrani et al., 2019). Of particular concern, extremely resistant strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae have been reported in China and Greece (Cheesman et al., 2017). Both of these strains were resistant to nearly all frontline antibiotics. The same study reported that shortly after those resistant strains were isolated, another K. pneumoniae strain that was resistant to all classes of antibiotics was detected in the United States of America. This is particularly concerning as medical science has no effective treatment against that strain and new therapies are urgently required. Similarly, methicillin resistant Staphyloccus aureus (MRSA) and extended spectrum β-lactamase resistant (ESBL) strains of some bacterial causes of pneumonia are now relatively common (Cheesman et al., 2017). The development of new therapies that are effective against these antibiotic-resistant species is urgently required.

2. An overview of bacterial respiratory diseases in South Africa

The incidence of TB is particularly high in southern Africa (Nanoo et al., 2015). Indeed, the WHO issues an annual global TB report on the 30 highest TB burden countries based on the number of cases and the severity of diseases burden (WHO, 2019a). Six southern African countries (Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe) are included in that list. South Africa has the highest overall number of cases (301,000 total infections), which corresponds to the higher population numbers in South Africa compared to the other southern African countries. The TB rate as a percentage of population is approximately 5% for South Africa, which is similar to the rates in Mozambique and Namibia, and lower than the rates in Lesotho. Interestingly, the rates in Zambia (3.5%) and Zimbabwe (2%) were substantially lower and may correlate to the higher average temperatures (particularly in winter) in those countries. Alternatively, the lower rates may be due to less effective and incomplete reporting of these diseases in those countries. Due to the higher temperatures, it is likely that people in those countries spend less time in groups indoors, thus decreasing pathogen transmission. The southern African infection rates are substantially higher than the global average of 1%, demonstrating the health burden that TB has in southern Africa.

Notably, the WHO statistics only report the cases of active TB. As only approximately 10% of M. tuberculosis infections cause the active form of the disease, the actual infection rate may be as high as 50% of the population, providing a vast reservoir of bacteria for potent transmission of TB. Other studies have reported higher incidence of M. tuberculosis infection in specific populations. Screening studies in an adult population (<30 years old) in a mining community detected M. tuberculosis infections in 89% of the population (Hanifa et al., 2009). A similar study screened adolescent school students (12–18 years old) in rural regions of the Western Cape province of South Africa, within 100 km of Cape Town, and reported nearly 60% of the students had latent TB infections (Mahomed et al., 2011). Both of these studies screened specific groups and these statistics do not necessarily represent the overall prevalence of latent M. tuberculosis infections in the entire southern Africa region and the prevalence in urban regions of southern Africa may be substantially different.

The Hanifa et al. study (2009) highlights the prevalence of TB on the mining industry. The conditions under which miners may work constitute ideal conditions for the transmission of M. tuberculosis. Miners often work in enclosed spaces underground for extended periods. If a miner has TB, airborne transmission is highly likely under those conditions. Furthermore, miners often share equipment, which may further facilitate the spread of the bacterium. High density lower socio-economic urban communities also have higher incidences of M. tuberculosis infections than other regions of southern Africa. High density living provides ideal conditions for airborne transmission, thereby increasing the likelihood of person to person transfer. Of concern, antibiotic resistant M. tuberculosis strains are highly prevalent in southern Africa, with >90% of new infections reported to be resistant to several frontline antibiotics (WHO, 2019a). The high prevalence of resistant M. tuberculosis strains contributes to the overall burden of the disease in the region. Not only is it more difficult to treat the disease in infected people, but this also allows for further transmission of the bacterium.

The relatively low level of childhood vaccination uptake in several of the southern African countries also contributes to the levels of TB in the region. The WHO report (2019a) estimates that only 59% of children below five years of age have been immunised against TB in South Africa. This contrasts dramatically with the worldwide vaccination rates where it has been estimated that more than 90% of children below the age of five years have been vaccinated for TB. The low vaccination uptake in South Africa is surprising given the incidence of TB in the region and subsidisation of TB vaccination programs by the South African government. Vaccination is relatively cheap and is generally readily available in most areas of the country. We were unable to find a further breakdown of the vaccination statistics on a geographical and ethnic basis, but it is likely that low levels of uptake in isolated and rural communities skew the statistics for the entire country. Isolated and rural communities often have limited access to clinical care, and when medical care is available, rural populations are often poor and may be unable to afford westernised health care. Instead, rural communities are often reliant on traditional healers. However, encouraging TB vaccination programs may be effective in reducing the infection levels in southern Africa, even amongst non-vaccinated people, by providing ‘herd immunity’, thereby reducing transmissibility.

Not surprisingly, the incidence of M. tuberculosis infections is also higher in health care workers than in the general population, due to their levels of exposure to respiratory pathogens. Indeed, one study estimated that the risk of contracting TB is approximately 2.5 times higher for medical professionals than the general population in several countries with similar socio-economic profiles as southern Africa (Joshi et al., 2006). Furthermore, that study demonstrated that specific health care sectors have substantially increased risks of contracting TB. In particular, the risks to workers in emergency departments, TB treatment facilities, clinical laboratories, and internal medicine departments were particularly high rates of infection. Within those departments, paramedics, nurses, patient attendants, ward attendants and radiology technicians had substantially increased risks of contracting a M. tuberculosis infection. Whilst that study examined the incidence of TB in the health care sector in other countries, it is likely that similar trends occur in southern Africa.

Immuno-compromised people also have higher rates of infection than non-immunocompromised people. Indeed, the WHO report on TB in the southern African countries (WHO, 2019a) estimated that 59% of individuals diagnosed with TB in 2018 in South Africa also had HIV/AIDS. Of further concern, people with HIV/AIDS had a substantially worse prognosis than the general population, with approximately twice the mortality rate. Whilst the WHO report did not break the data down on the basis of age, it is likely that similar trends would occur in children and in the elderly. Both of these groups have lower immuno-competence than healthy adults. Thus, they are likely to have higher incidences of TB, and higher rates of mortality once they contract a M. tuberculosis infection. However, we were unable to find statistics to support this and further studies are needed for confirmation.

The other bacterial respiratory diseases generally follow similar trends to other countries with similar socio-economic profiles. As with other regions of the world, widespread diphtheria and pertussis vaccination programs in children have substantially decreased the incidence of those diseases in southern Africa. Indeed, between January 2008 and March 2015, only four cases of diphtheria were reported in South Africa. An outbreak of diphtheria occurred in South Africa in March 2015, with fifteen confirmed cases in rural Kwa-Zulu Natal, of which four died (Mahomed et al., 2015). All but four of the infected people were either not vaccinated, or their vaccinations were out of date. The outbreak was rapidly contained and the incidence rates have remained low since. Similarly low rates of infection occurred throughout other southern African countries across the same period.

Pertussis is far more common than diphtheria in southern Africa. It is difficult to find incidence statistics for individual countries in southern Africa as the WHO provides figures for the African global region instead. According to the WHO, 14 million cases of pertussis were reported from a population of approximately one billion people, which equates to an infection rate of 1.4% of the population. However, vaccination programs are widespread in South Africa and have a far greater take up rate in southern Africa than in central, eastern and western Africa (WHO, 2019c), so it is likely that the incidence in South Africa (and other southern African countries) is substantially less than this. Pertussis is substantially more common in children than in adults and is one of the most common diseases in children under five years of age. It also has higher incidences in immuno-compromised people than in the general population. A recent study screened children hospitalised for respiratory illnesses in South Africa and reported that pertussis was the cause of approximately 7% of the cases of respiratory illness (Muloiwa et al., 2016). The rate was significantly higher in HIV positive children (15.8%) and in HIV exposed but negative children (10.9%) than in HIV unexposed children (5.4%). Notably, there have been marked recent increases in the incidence of pertussis in the WHO African world region. Indeed, the number of reported B. pertussis infections in that region has increased from approximately 1.5 million to over 14 million between 2016 and 2018 (WHO, 2019d). Although specific figures for South Africa are not available from the WHO, it is likely that it has similar trends for those of the rest of the Africa region. It is likely that decreased rates of pertussis vaccination uptake in recent years may contribute to this trend. Indeed, a recent report by the Centre for Communicable Diseases (2018) reported that pertussis vaccination rates in South Africa had decreased to 66% of the population in 2016, allowing for the resurgence of the disease in the region.

Bacterial pneumonia is common in both children and adults in southern Africa and it is the most common cause of hospitalisation in South Africa. Indeed, approximately 12 million children were hospitalised and 1.2 million children died from bacterial pneumonia in 2010 in South Africa (Dept of Paediatrics and Child Health, South Africa, 2019). The same study also reported that bacterial pneumonia is the second most common cause of death in South African adults. The disease is substantially more common in immune-compromised individuals (both children and adults).

Pertussis and bacterial pneumonia transmission trends are similar to TB. High density urban living allows for efficient transmission of these diseases, therefore the incidence is higher under those conditions. Unfortunately, we were unable to locate occupation specific statistics as reported for TB and further research is required in that area. However, it is likely that similar trends occur (i.e. higher rates in occupations that require workers to work together in confined spaces such as mining; high rates in health care sector professionals through greater contact with infected people). However, these trends have not been reported for pertussis and bacterial pneumonia and further studies are required to confirm this.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Search strategy

Our study aimed to identify southern African plants used traditionally to treat bacterial respiratory diseases in humans. A systematic search was undertaken using a variety ethnobotanical books (Smith, 1888; Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Van Hutchings et al., 1996; Von Koenen, 2001; Ngwenya et al., 2003; Wyk et al., 2009) and ethnobotanical reviews (Hulley and Van Wyk, 2017; De Beer and Van Wyk, 2011; Nortje and Van Wyk, 2011; Philander, 2011; Van Wyk, 2008). Ethnobotanical research articles published prior to June 2020 were also searched via Google-Scholar, Science-Direct, PubMed and Scopus using the following terms as filters, and were searched both alone and as combinations: “South African”, “medicinal plant”, “traditional medicine”, “ethnobotany”, “respiratory infection” “tuberculosis”, “pneumonia”, “bacterial pneumonia”, “pertussis”, “diphtheria”, “whooping cough”. All terms were searched alone and as combinations.

Each plant species identified by this initial search were subjected to a further literature review to establish the extent (if any) of the scientific research into the efficacy of that species. Specific criteria to filter studies included the terms ethnomedicine, southern African medicinal plants and other key words related to bacterial respiratory infections and the specific pathogens.

3.2. Eligibility criteria

A screening of publication titles was initially performed, and eligible publications were selected. The abstracts of were then read to ensure that the selected publications met the eligibility criteria. Full text manuscripts were retrieved for all publications that met the eligibility requirements and these were further studied.

3.2.1. Inclusion criteria

To meet the eligibility criteria for this study, a publication had to meet the following inclusion criteria:

-

•

Only English language publications published prior to June 2020 were used in the preparation of this review.

-

•

This study is non-biased and does not have taxonomic preference (although several of the studies we review targeted specific families or genera).

-

•

For the ethnobotanical studies, the plant species must be stated to be used against the specific bacterial respiratory diseases examined in this study, rather against generic symptoms.

-

•

For the screening studies, preparations prepared from plant extracts must have been screened against at least one of the pathogens responsible for the bacterial respiratory diseases. Alternatively, studies that tested the plant preparations against human or animal models with the bacterial respiratory diseases were also included in this study.

-

•

For introduced species to be included in this report, they must either be naturalised or widely cultivated, and there must be documented evidence that they are commonly used by at least one southern African ethnic group to treat viral respiratory disease.

3.2.2. Exclusion criteria

Studies with the following criteria were excluded from this study:

-

•

Studies where the species identity was in doubt. By necessity, several relatively old publications were searched (e.g. Smith, 1888; Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962). Where possible, the species names were confirmed or updated using the Plant List website (http://www.theplantlist.org/). Where a species name could not be definitively verified, that species was omitted from this study.

-

•

Only plant species definitively described as being used to treat specific bacterial respiratory diseases are included in this study. Due to symptom similarity with numerous diseases, when a plant was described as being used to treat symptoms consistent with bacterial respiratory diseases without specifying the diseases they are used to treat were excluded from this study.

-

•

Whilst plant species that are not native to southern Africa are included in this study, introduced plant species were excluded unless there is evidence of their usage in at least one southern African traditional healing system and their widespread cultivation in southern Africa.

3.3. Data collection

Ethnopharmacological studies from southern Africa that are linked with the treatment of bacterial respiratory disease were collected and examined in this study. Additionally, studies testing the activity of the southern African medicinal plants against the bacterial respiratory pathogens, or against infected human or animal models, were examined, irrespective of the study origin. The following data was collected:

-

•

Genus, species and family name for each species examined in the individual publications. All species names were standardised using the Plant List website (http://www.theplantlist.org/).

-

•

Ethnic grouping that traditionally used the plant species medicinally. Where possible, the common and ethnic names were also collected.

-

•

The plant part used and the method of preparation were collected (where available).

-

•

For screening studies, the bacterial pathogen species and (where possible) the strain were listed and the MIC values (where available) are included.

-

•

For animal and human trial studies, the animal model (where appropriate), route of administration, doses and toxicity data (where available) was noted.

All data was managed using Excel® software.

4. Results

4.1. South African medicinal plants used traditionally to treat bacterial respiratory diseases

One hundred and eighty-seven southern African plants which are used in at least one southern African traditional healing system to treat bacterial respiratory infections were identified following an extensive literature search (Table 1 ). As indicated in our review of southern African plants to treat viral respiratory infections (Cock and Van Vuuren, part one), several pathogenic respiratory diseases exhibit generic symptoms that are common with other bacterial diseases, as well as viral respiratory diseases. For example, the early stage symptoms of TB are often similar to those of influenza or severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Similar symptoms are also evident for numerous other non-respiratory diseases including bubonic plague, Lyme disease, malaria, measles, rabies, and the early phases of AIDS. As ethnobotanical texts may report the usage of plant species to treat the symptoms of a disease, the specific disease treated is often not definitive. For this study, we have only included plant species that have specifically been reported for the treatment of bacterial respiratory infections in humans. Where the disease pathogen targeted by a plant is ambiguous, we have excluded that species from this study. Thus, it is likely that this list underestimates the number of plant species used to treat bacterial respiratory disease.

Table 1.

South African plants used traditionally to treat bacterial respiratory illnesses.

| Plant species | Family | Common name(s) | Plant part used | Used for | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abrus precatorius subsp. africanus Verdc. | Fabaceae | Bead vine, coral bead plant, coral bean, crabs eye, licorice vine, love bean, lucky bean creeper, prayer beads, weather vine (English), umkhokha (Zulu) | Leaves, roots | Used to treat TB and whooping cough. Preparation and application not specified. | Madikizela et al. (2013) |

| Abutilon angulatum (Guill. & Perr.) Mast. | Malvaceae | Unknown | Root | Used to treat bacterial pneumonia. Preparation and application are not specified. | Von Koenen (2001) |

| Acacia eriloba E.Mey. | Fabaceae | Camel thorn, giraffe thorn (English), kameeldoringboom (Afrikaans) | Leaves | Leaf infusions are drunk to treat bacterial pneumonia. | Von Koenen (2001) |

| Acacia nilotica (L.) Delile | Fabaceae | Redheart, scented thorn (English), lekkerreulpeul (Afrikaans) | Root | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application are not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Acacia xanthophloea Benth. | Fabaceae | Fever tree (English) | Bark | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application are not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Aclepias crispa P.J.Bergius | Apocynaceae | witvergeet, kalmoes (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Used to treat bacterial pneumonia. Preparation and application are not specified. | Hulley and Van Wyk, 2017 |

| Acorus calamus L. | Acoraceae | Sweet flag (English), makkalmoes (Afrikaans), ikalamuzi (Zulu) | Root | Volatile compounds produced from the root are used to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Adenia fruticosa Burtt Davy | Passifloraceae | Green-stem (English) | Not specified | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Ajuga ophrydis Burch. ex Benth. | Lamiaceae | Senyarrla (Southern Sotho) | Roots | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Kose et al. (2015) |

| Allium cepa L. | Amaryllidaceae | Onion (English) | Bulb | Consumed to treat whooping cough. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Allium sativum L. | Amaryllidaceae | Garlic (English) | Bulb | Consumed to treat whooping cough and TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Aloe arborescens Mill. | Xanthorrhoeaceae | Krantz aloe (English), kransaalwyn (Afrikaans), ikalene (Xhosa), inkalane, umhlabana (Zulu) | Leaves | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Aloe ferox Mill. | Xanthorrhoeaceae | Cape aloe (English), Bitteraalwyn, Winkelaalwyn (Afrikaans), iKhala (Xhosa), iNhlaba (Zulu) | Leaves | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Aloe maculata All. | Xanthorrhoeaceae | Soap aloe, zebra aloe (English) | Leaves | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Aloe noblis Haw. | Xanthorrhoeaceae | Golden toothed aloe | Leaves | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Aloe plicatilis (L.) Mill. | Xanthorrhoeaceae | Fan aloe, Franschhoek aloe (English), waaieraalwyn, Franschoekaalwyn, bergaalwyn, tongaalwyn (Afrikaans) | Leaves | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Anginon difforme (L.) B.L.Burtt. | Apiaceae | Wildeanys (Afrikaans) | Leaves | Leave infusions were drunk by the Nama to treat TB. | Nortjie and Van Wyk (2015) |

| Aptosimum depressum Burch. ex Benth. | Scrophulariaceae | Unknown | Not specified | An infusion was used as a gargle to treat diphtheria. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Artemisia afra Jacq. ex Willd. | Asteraceae | African wormwood (English), als, alsem, wildeals (Afrikaans), lengana (Sotho, Tswana), umhlonyane (Xhosa, Zulu) | Leaves | The leaves are boiled and the steam inhaled to treat whooping cough and diphtheria. The resultant infusion can also be drunk for the same purposes. | Von Koenen, 2001; McGaw et al., 2008; |

| Aspalathus cordata (L.) R.Dahlgren | Fabaceae | Unknown | Leaves | An infusion is drunk to treat whooping cough. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Aspalathus linearis (Burm.f.) R.Dahlgren | Fabaceae | Red bush, bush tea (English), Rooibos (Afrikaans) | Leaves | An infusion is drunk to treat TB and whooping cough. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Asparagus africanus Lam. | Asparagaceae | Bush asparagus (English) | Root | Root infusions are consumed several times per day to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Madikizela et al., 2013; Hulley and Van Wyk, 2017 |

| Asparagus capensis L. | Asparagaceae | Katdoring (Afrikaans) | Root | Root infusions are consumed several times per day to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Philander, 2011; Hulley and Van Wyk, 2017 |

| Asparagus densiflorus (Kunth) Jessop | Asparagaceae | Katdoring (Afrikaans) | Root | Root infusions are consumed to treat TB. | Hulley and Van Wyk, 2017 |

| Asparagus falcatus L. | Asparagaceae | Unknown | Leaves and roots | Root infusions are consumed to treat TB. | Pallant and Steenkamp, 2008; Madikizela et al., 2013; |

| Asparagus linearis (Brum.f.) R.Dahlgren | Asparagaceae | T'nuance, katdoring (Afrikaans) | Roots | Root infusions are consumed to treat TB. | Van Wyk (2008) |

| Asparagus retrofractus L. | Asparagaceae | Ming fern (English) | Root | Root infusions are consumed to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Asparagus setaceus (Kunth) Jessop | Asparagaceae | Asparagus fern, climbing fern, lace fern (English) | Root | Root infusions are consumed several times per day to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Asparagus striatus (L.f.) Thunb. | Asparagaceae | Bergappel, bergappeltjie, bobbejaanappel (Afrikaans) | Root | Root infusions are consumed several times per day to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Asparagus suaveolens (Burch.) Baker | Asparagaceae | Bushveld Asparagus, wild aspoaragus (English), katdoring (Afrikaans), mvane (Xhosa) | Root | Root infusions are consumed to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Astridia velutina (L.Bolus) Dinter | Aizoaceae | Unknown | Sap | used to treat diphtheria. Preparation and application not specified. | Von Koenen (2001) |

| Buddleja saligna Willd. | Scrophulariaceae | False olive (English), witolien (Afrikaans), lelothwane (Southern Sotho), ungqeba (Xhosa), igqeba-elimhlope (Zulu) | Leaves, stems | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Callilepis laureola DC | Asteraceae | Oxe-eye daisy (English), Wile margriet (Afrikaans), amafuthomhlaba, ihlamvu, impila (Zulu) | Root | Preparation and application methods are not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Capparis tomentosa Lam. | Capparaceae | Wooly caper-bush (English), wollerige kapperbos, wag-‘n-bietjie (Afrikaans), inkunzi-ebomvu, iqwaningi, umqoqolo, ukhokhwana, umabusane (Zulu), imfishlo, intshihlo, intsihlo, umpasimani (Xhosa) | Bark, Roots | The bark is burned and the smoke is inhaled to treat TB. The Venda also drank a root decoction for the same purpose. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Pallant and Steenkamp, 2008 |

| Carissa edulis (Forssk.) Vahl. | Apocynaceae | Simple-spined num-num, climbing num-num, small num-num (English), enkeldoringnoemnoem, ranknoemnoem, kleinnoemnoem (Afrikaans), mothokolo (North Sotho), murungulu (Venda) | Root, leaves | A root decoction is used by the Venda to treat TB. Leaf juice was gargled to treat diphtheria | Pallant and Steenkamp, 2008; Van Wyk, 2008 |

| Carpobrotus acinaciformis (L.) L.Bolus | Aizoaceae | Eland's sourfig (English), elandssuurvy (Afrikaans) | Leaves | The boiled fruit is consumed to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Carpobrotus edulis (L.) N.E.Br. | Aizoaceae | Sour fig, Cape fig, Hottentot's fig (English), vyerank, ghaukum, ghoenavy, hotnotsvye, Kaapvy, perdevy, rankvy (Afrikaans), ikhambi-lamabulawo, umgongozi (Zulu) | Leaves | A leaf decoction is consumed to treat diphtheria. Leaf juice is consumed to treat TB. | al.Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Van Wyk et al., 2009; Philander, 2011; Nortjie and Van Wyk, 2015 |

| Cassine aethiopica Thunb. | Celastraceae | Saffron wood, forest saffron (English), saffraan, bossafraan (Afrikaans) | Leaves | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Cephalaria pungens Szabó | Caprifoliaceae | Unknown | Roots | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Chaetachme aristata Planch. | Ulmaceae | Thorny elm (English), basterwitpeer (Afrikaans) | Leaves | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Dzoyem et al. (2016) |

| Chamaecrista mimosoides (L.) Greene | Fabaceae | Boesmantee (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Used to treat bacterial pneumonia. Preparation and application are not specified. | Von Koenen (2001) |

| Chenopodium ambrosioides L. | Chenopodiaceae | Wormsalt (English), sinkingbossie (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Used to treat bacterial pneumonia. Preparation and application are not specified. | al.; Von Koenen, 2001; McGaw et al., 2008 |

| Chironia baccifera L. | Gentianaceae | Bitterbos, skilparbos (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Infusions are used to treat TB and pneumonia. | Hulley and Van Wyk, 2017 |

| Chrysanthemum frutescens L. | Asteraceae | Paris daisy (English) | Roots | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Chrysanthemum segetum L., | Asteraceae | Corn marigold (English) | Leaves | Decoctions are drunk to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J.Presl. | Lauraceae | Camphor tree (English), kanferboom (Afrikaans), uroselina (Zulu) | Leaves. Essential oil (distilled from the wood) | The leaves are smoked by the Southern Sotho to treat TB. The bark is used to treat bacterial pneumonia, Preparation and application not specified. | Philander, 2011; Van Wyk et al., 2009; Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962 |

| Cissampelos capensis L.f. | Menispermaceae | Dawidjies, fynblaarklimop (Afrikaans) | Leaves | Infusions are drunk to treat TB. | Hulley and Van Wyk, 2017 |

| Cliffortia odorata L.f. | Rosaceae | Wildewingerd (Afrikaans) | Not specified | An infusion is drunk to treat diphtheria. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Combretum molle R.Br. ex G.Don. | Combretaceae | Velvet bush willow (English), fluweelboswilg, basterrooibos (Afrikaans), mokgwethe (Sotho), mugwiti (Venda), umBondwe-omhlope (Zulu) | Bark | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Combretum platypetalum Welw. ex M.A. Lawson | Combretaceae | Unknown | Root | Root decoctions are drunk to treat bacterial pneumonia | Von Koenen (2001) |

| Croton pseudopulchellus Pax | Euphorbiaceae | Small lavender fever-berry (English), kleinlaventelkoorsbessie, sandkoorsbessie (Afrikaans), uHubeshane (Zulu) | Leaves | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Cryptocarya latifolia latifolia Sond. | Lauriaceae | Bastard stinkwood, broad-leaved aurel, broad-leaved quince (English), baster-stinkhout, basterswartstinkhout, breëblaarkweper, pondo-kweper (Afrikaans),umgxaleba, umgxobothi (Xhosa), umhlangwenya, umkhondweni, umdlangwenya (Zulu), | Bark | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Cyclopia genistoides (L.) Vent. | Fabaceae | Honeybush tea (English), heuningbos (Afrikaans) | Leaves | infusions are drunk as an expectorant in people with TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Dahlia pinnata Cav. | Asteraceae | Garden dahlia (English) | Flowers | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Datura metel L. | Solanaceae | Thorn apple, angel's trumpet (English) | Root | Dried roots are smoked to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Dicoma capensis Less. | Asteraceae | Karmadik, baarbos, sandsalie (Afrikaans) | Leaves | Decoctions are drunk to treat TB. | Nortjie and Van Wyk (2015) |

| Dichrostachys cinerea (L.) Wight & Arn. | Fabaceae | Kalahari Christmas tree, sickle bush, bell mimosa, Chinese lantern tree (English) | Leaves and roots | Leaves and roots are burned and the smoke inhaled to treat TB and bacterial pneumonia. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Von Koenen, 2001; |

| Diplorhynchus condylocarpon (Müll.Arg.) Pichon | Apocynaceae | Wild rubber, horn-pod tree (English), horingpeulbos, melkbos (Afrikaans), muthowa (Venda) | Not specified | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application method not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Dodonaea viscosa (L.) Jacq. | Sapindaceae | Sand olive (English), sandolien, ysterbos (Afrikaans), mutata-vhana (Venda) | Leaves, twigs | A decoction is drunk to treat TB and diphtheria. Also useful for the treatment of bacterial pneumonia. | al.Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; McGaw et al., 2008; Hulley and Van Wyk, 2017 |

| Drosera capensis L. | Droseraceae | Cape sundew (English), sondouw (Afrikaans) | Leaves | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Ekebergia capensis Sparm. | Meliaceae | Cape ash, dogplum (English), essenhout (Afrikaans), mmidibidi (Sotho) | Leaves bark, roots | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Elytropappus rhinocerotis (L.f) Less. | Asteraceae | Rhinoceros bush (English) | Unspecified | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application methods are not specified. | Hulley and vanWyk, 2017 |

| Empleurum unicapsulare (L.f.) Skeels | Rutaceae | Bergboegoe (Afrikaans) | Unspecified | Used to treat bacterial pneumonia. Preparation and application methods are not specified. | Hulley and vanWyk, 2017 |

| Erigeron canadensis L. | Asteraceae | Horseweed, coltstail, marestail, butterweed (English) | Leaf | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Eriocephalus africanus L. | Asteraceae | Kapokbos, skaapkaroo (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Infusions are used to treat TB. | Hulley and vanWyk, 2017 |

| Erythrina humeana Spreng. | Fabaceae | Umsinsana (Zulu) | Not specified | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Corrigan et al. (2011) |

| Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | Myrtaceae | Southern blue gum, Tasmanian blue gum (English) | Leaves | The leaves are boiled and the vapour is inhaled to treat TB and diphtheria. | Van Wyk, 2008; Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962 |

| Eucela natalensis A. DC. | Ebenaceae | Natal guarri, Natal ebony, large-leaved guarri (English), Natalghwarrie, berggwarrie, swartbasboom (Afrikaans), umTshekisani, umKhasa (Xhosa), iDungamuzi, iChitamuzi, umZimane, umTshikisane, inKunzane, inKunzi-emnyama, umHlalanyamazane, umAnyathi (Zulu) | Roots | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Euphorbia heterophylla L. | Euphorbiaceae | Japanese poinsettia, desert poinsettia, painted spurge, milkweed (English) | Leaves and flowers | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Euphorbia neriifolia L. | Euphorbiaceae | Milk hedge, milk bush, oleander spurge, oleander-leaved euphorbia (English), melkbos (Afrikaans) | Stem latex | Used to treat whooping cough. Preparation and application method not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Felicia filifolia (Vent.) Burtt Davy | Asteraceae | Steenbokbossie, vaderlandsrapuisbos (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Used for the treatment of TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Hulley and Van Wyk, 2017 |

| Ficus carica L. | Moraceae | Common fig (English) | Leaves and roots | A decoction of the roots and leaves is drunk to treat diphtheria. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Hulley and Van Wyk, 2017 |

| Ficus sur Forssk | Moraceae | Cape fig, broom cluster fig (English) | Root and bark | The Zulu drink a decoction of the root and bark to treat TB. | al.Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Pallant and Steenkamp, 2008; Madikizela et al., 2013 |

| Ficus sycomorus L. | Moraceae | Sycamore fig, common cluster fig, mulberry fig (English), trosvy, geelrriviervy, geelstamvy, gewone trosvy, wildevyeboom, sycomorusvy (Afrikaans), mogo, mogoboya, mohlole (Sotho), muhuvhoya, muhuyu, muhuyu-lukuse, mutole, muvhuyu-vhutwa (Venda), mogoboya, umkhiwane isikhukhuboya, umncongo, umkhiwane (Zulu) | Fruit | A fruit infusion is drunk by the Venda to treat TB. | Pallant and Steenkamp (2008) |

| Galenia africana L. | Aizoaceae | Yellow bush (English), brakkraalbossie, geelbos, kraalbos, muisbos, muisgeelbossie, perdebos (Afrikaans), iqina (Xhosa) | Leaves | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Garcinia polyantha Oliv. | Clusiaceae | Unknown | Bark | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Ginkgo biloba L. | Ginkgoaceae | Ginkgo | Leaves | Decoctions and infusions are drunk to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra glabra L. | Fabaceae | Liquorice, licorice (English) | Rhizome | Root infusions are used to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Van Wyk et al., 2009 |

| Gomphocarpus fruticosus (L.) W.T.Aiton | Apocynaceae | Milkweed (English), melkbos, tontelbos (Afrikaans), lebegana, lereke-la-ntja (Sotho), modimolo (Southern Sotho), umsinga-lwesalukazi (Zulu) | Leaves | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application method not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Van Wyk et al., 2009; |

| Gunnera perpensa L. | Gunneraceae | Wild rhubarb, river pumpkin (English), wilde ramenas, ravierpampoen (Afrikaans), qobo (Sotho), rambola-vhadzimu (Venda), iphuzi, ighobo (Xhosa), ugobhe (Zulu) | Roots | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application method not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Gymnosporia buxifolia (L.) Szyszył. | Celestraceae | lemoendoring, wondedoring, pendoringbos (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Hulley and Van Wyk, 2017 |

| Helianthus tuberosus L. | Asteraceae | Jerusalem artichoke (English) | Root/tuber | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Helichrysum crispum (L.) D.Don. | Asteraceae | Hottentot's Bedding (English), Hotnotskooigoed, Hottentotskooigoed, Hottentotskruie, Kooigoed (Afrikaans) | Leaves, whole plant | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Helichrysum imbricatum (L.) Less. | Asteraceae | Gold-and-silver (English) | Not specified | Used as a remedy for whooping cough. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; McGaw et al., 2008; |

| Helichrysum krausii Sch. Bip. | Asteraceae | Straw everlasting (English), sewejaartjie (Afrikaans), isipheshane, isiqoqo (Zulu) | Flowers and seeds | Dried flowers and seeds are smoked to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; McGaw et al., 2008; |

| Helichrysum melanacme DC. | Asteraceae | Hotnotskooigoed (Afrikaans) | Leaves, whole plant | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Helichrysum nudifolium (L.) Less. | Asteraceae | Everlastings (English), hottentotsteebossie, kooigoed (Afrikaans), isicwe, indlebe zebhokwe, undleni (Xhosa), icholocholo, imphepho (Zulu) | Leaves, whole plant | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Helichrysum odoratissimum (L.) Sweet | Asteraceae | Everlantings (English), kooigoed (Afrikaans) imphepho (Zulu) | Leaves, whole plant | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Helichrysum vestitum (L.) Willd. | Asteraceae | Cape snow (English) | Not specified | Used to treat diphtheria. Preparation. Application not specified. | ; Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; McGaw et al.., 2008 |

| Helipterum eximium (L.) DC. | Asteraceae | Unknown | Not specified | Used to treat diphtheria. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Helipterum speciosissimum (L.) DC. | Asteraceae | Unknown | Not specified | Used to treat diphtheria. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Helipterum variegatum DC. | Asteraceae | Unknown | Not specified | Used to treat diphtheria. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Hermannia salviifolia L.f. | Malvaceae | Katjiedrieblaar (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Used to treat bacterial pneumonia. Preparation and application not specified. | Hulley and Van Wyk, 2017 |

| Hoodia gordonii (Masson) Sweet ex Decne. | Apocynaceae | Hoodia, ghaap, kakimas (Afrikaans) | Fleshy stems | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Hoodia pilifera subsp. annulata (N.E. Br.) Bruyns | Apocynaceae | Unknown | Fleshy stems | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application method not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Hypericum perforatum L. | Hypericaceae | St John's wort (English) | Roots, leaves and flowers | Decoctions and infusions are drunk to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Indigofera tinctoria L. | Fabaceae | True indigo (English) | Juice | consumed to treat whooping cough. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Madikizela et al., 2013; |

| Jatropha zeyheri Sond. | Euphorbiaceae | Verfbol (Afrikaans), sefapabadia (Sotho), ugodide (Zulu) | Unspecified | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Lactuca sativa L. | Asteraceae | Lettuce (English) | Whole plant | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Lannea edulis (Sond.) Engl. | Anacardiaceae | Wild grape (English), wildedruif (Afrikaans), muporotso (Venda) | Root | Decoctions and infusions of the root bark is drunk to treat whooping cough. | Van Wyk et al. (2009) |

| Leonotis leonoris (L.) R.Br. | Lamiaceae | Wild dagga (English), wildedagga, duiwelstabak (Afrikaans), mvovo (Xhosa), uyshwala-bezinyoni (Zulu) | Leaves and stems | A tincture is drunk to treat TB and whooping cough. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Pallant and Steenkamp, 2008; |

| Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit | Fabaceae | Wild tamarind, wild lead tree (English) | Bark leaves, seeds | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Dzoyem et al. (2016) |

| Lessertia frutescens (L.) Goldblatt & J.C. Manning | Fabaceae | Keurtjie, beeskeurtiebos, kankerbos (Afrikaans) | Not specified | An infusion is used to treat TB. | Hulley and Van Wyk, 2017 |

| Leyssera gnaphalioides L. | Asteraceae | Skilpadteebossie, hongertee, duinetee, teringteebos Afrikaans) | Leaf | An infusion is drunk to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962); McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Malva neglecta Wallr. | Malvaceae | Low mallow (English) | Roots | Decoctions and infusions are drunk to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Malva paviflora L. | Malvaceae | Marshmallow, cheeseweed mallow, little mallow, small flower mallow (English) | Roots | Decoctions and infusions are drunk to treat TB. | Von Koenen (2001) |

| Matricaria chamomilla L. | Asteraceae | German chamomile, wild chamomile, scented mayweed (English) | Not specified | Used to treat diphtheria and TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Maytenus heterophylla (Eckl. & Zeyh.) N.Robson | Celestraceae | Gewone pendoring (Afrikaans) | Leaves | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Melilotus alba Ledeb. | Fabaceae | White sweet clover (English) | Whole plant | Decoctions and infusions are drunk to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Melolobium candicans (E.Mey.) Eckl. & Zeyh. | Fabaceae | Wild dagga (English), wildedagga (Afrikaans) | Leaves and stems | A decoction of the leaves and stems is drunk to treat TB. | De Beer and Van Wyk (2011) |

| Mentha longifolia (L.) L. | Lamiaceae | Wild mint (English), kruisement, balderjan (Afrikaans), koena-ya-thabo (Sotho), inixina, inzinziniba (Xhosa), ufuthana, lomhlanga (Zulu) | Leaves, roots and stems | Used to treat TB, whooping cough and diphtheria. Preparation and application method not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Mesembryanthemum tortuosum L. | Aizoaceae | Koegoed, kanna (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Hulley and Van Wyk2017 |

| Montinia caryophyllacea Thunb. | Montiniaceae | Pepper-bush, wild clove bush (English), bergklapper, peperbos (Afrikaans) | Leaves | The dried pulverised leaves are used as a snuff to treat TB. | Von Koenen (2001) |

| Mundulea sericea (Willd.) A.Chev. | Fabaceae | Cork bush, silver bush, (English), kurkbos, olifantshout, visboontjie, visgif, mangaanbos (Afrikaans), mosetla-thlou (Sotho), mukunda-ndou (Venda), umsindandlovu (Zulu) | Bark and roots | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Nasturtium officinale R.Br. | Brassicaceae | Watercress (English) | Whole plant | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Nicotiana glauca Graham | Solanaceae | Mustard tree, tree tobacco (English), tabakboom, wildetabak, volstruisgifboom (Afrikaans), mohlafotha (Sotho) | Leaves | Powdered leaves are used as a snuff to treat TB. | Von Koenen (2001) |

| Nidorella anomala Steetz | Asteraceae | Unknown | Whole plant | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Nidorella auriculata DC. | Asteraceae | Unknown | Whole plant | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Olea europea L. | Olacaceae | Wild olive (English) olienhout (Afrikaans), mohlware (Sotho), umnquma (Zulu, Xhosa), mutlhwari (Venda) | Leaves | A leaf decoction is used as a gargle to treat diphtheria. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962); Von Koenen (2001); |

| Oncosiphon suffruticosum (L.) Källersjö | Asteraceae | Stinkkruid, wirmkruid (Afrikaans) | Whole plant | An infusion is drunk to treat bacterial pneumonia. | Van Wyk et al. (2009) |

| Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. | Cactaceae | Indian pear (English), turksvy (Afrikaans) | Leaves | Leaf infusions are drunk to treat whooping cough. | Von Koenen (2001) |

| Opuntia vulgaris Mill. | Cactaceae | Prickly pear (English) | Leaves | A leaf infusion is consumed to treat whooping cough. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Pegolettia baccharidifolia Less. | Asteraceae | Ghwarrieson, heuningdou (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Used to treat bacterial pneumonia. Preparation and application not specified. | Hulley and Van Wyk2017 |

| Pelargonium graveolens L'Hér. | Geraniaceae | Rose geranium (English), wildemalva (Afrikaans) | Leaves | Leaves are steamed and vapours are inhaled to treat TB. | Van Wyk et al. (2009) |

| Pelargonium myrrhifolium (L.) L'Hér | Geraniaceae | Unknown | Tuber | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Van Wyk (2008) |

| Pelargonium ramosissimum Willd. | Geraniaceae | Dassieboegoe (Afrikaans) | Tuber | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Van Wyk (2008) |

| Pelargonium rentiforme Curtis | Geraniaceae | Kidney-leaved pelargonium (English), rooirabas (Afrikaans), iyeza lesikhali, ikubalo, umsongelo (Xhosa) | Tuber | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Pelargonium sidoides DC. | Geraniaceae | Black pelargonium (English), kalwerbossie, rabassam (Afrikaans), ikubalo, iyeza lesikhali (Xhosa), khoara-e-nyenyane (Southern Sotho) | Tuber | Used to treat TB and pneumonia. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008); Hulley and Van Wyk2017 |

| Pelargonium triste (L.) L'Hér | Geraniaceae | Kaneelbol, rooirabas (Afrikaans) | Tuber | Used to treat TB and pneumonia. Preparation and application not specified. | Philander (2011) |

| Pentanisia prunelloides (Klotzsch) Walp. | Rubiaceae | Wild verbena (English), sooibrandbossie (Afrikaans), setimamollo (Sotho), icimamlilo (Zulu) | Roots | The Xhosa drink a root infusion to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962); Van Wyk et al. (2009); Philander (2011); Madikizela et al. (2013) |

| Pentzia incana (Thunb.) Kuntze | Asteraceae | Skaapkaroobos, ankerkaroo, kleinskaapkaroobos (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Used to treat bacterial pneumonia. Preparation and application not specified. | Hulley and Van Wyk2017 |

| Pharnaceum lineare L. f. | Molluginaceae | Droëdaskruie (Afrikaans) | Not specified | An infusion is consumed to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962); Van Wyk (2008); |

| Polycarpaea corymbosa (L.) Lam. | Caryophyllaceae | Old man's cap (English) | Not specified | Used to treat TB. Treatment and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Polygala fruticosa P.J. Bergius | Polygonaceae | Butterfly bush, heart-leaf polygala (English), ertjieblom (Afrikaans), ulopesi, ulapesi, umabalabala (Xhosa), ithethe (Zulu) | Roots | Root decoctions are used by the Zulu to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962); Madikizela et al. (2013); |

| Polygala myrtifolia L. | Polygonaceae | September bush (English), septemberbossie, augustusbossie, blouertjie, langelede (Afrikaans), ulopesi, ulapesi, umabalabala (Xhosa), uchwasha (Zulu) | Aerial parts | Used to treat TB. Treatment and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Polygonum aviculare L. | Polygonaceae | Knotgrass, bird weed, pig weed (English) | Not specified | Used to treat TB. Treatment and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Polysiphonia virgata (C. Agardh.) Sprengel | Rhodomeleaceae | Red algae (English) | Not specified | Used to treat TB. Treatment and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Protea nitida Mill. | Protaceae | Waboom (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Used to treat TB and pneumonia. Treatment and application not specified. | Hulley and Van Wyk2017 |

| Prunus africana (Hook.f.) Kalkman | Rosaceae | Red stinkwood, African almond (English), rooistinkhout, Afrika-amandel, Wilde-kersieboom (Afrikaans), inyazangoma-elimnyama, inkokhokho, ngubozinyeweni, umdumezulu (Zulu); uMkakase, inyazangoma, itywina-elikhul, Umkhakhase (Xhosa), mogohloro (Sotho), mulala-maanga (Venda) | Bark | Used to treat TB. Treatment and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Prunus cerasus L. | Rosaceae | Sour cherry, tart cherry, dwarf cherry (English) | Leaf | Used to treat TB. Treatment and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Prunus persica (L.) Batsch | Rosaceae | Peach tree (English) | Leaves | Used to treat whopping cough. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Pteronia camphorata (L.) L. | Asteraceae | Wakkerbos, koorsbos (Afrikaans) | Leaves and twigs | Leaf and twig infusions are drunk to treat TB. | Nortjie and Van Wyk (2015) |

| Quercus spp. | Fagaceae | Oak (English) | Bark | The bark is boiled and the fumes inhaled to treat diphtheria | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Rapanea melanophloeos (L.) Mez | Primulaceae | Cape beech (English); boekenhout, beukehout (Afrikaans), isiCalabi, umaPhipha, iKhubalwane, isiQalaba sehlati (Zulu), isiQwane sehlati (Xhosa) | Leaves and twigs | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Rhynchosia caribaea (Jacq.) DC. | Fabaceae | Unknown | Roots | A root extract is consumed to treat bacterial pneumonia. | Von Koenen (2001) |

| Rhamnus prinoides L'Hér | Rhamnaceae | Mofifi (Southern Sotho) | Branches | Used to treat bacterial pneumonia. Preparation and application not specified. | Kose et al. (2015) |

| Ricinus communis L. | Euphorbiaceae | Castor bean, castor oil plant (English) | Leaves | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Rumex crispus L. | Polygonaceae | Yellow dock (English) | Whole plant | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application methods are not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Salvia africana-lutea L. | Lamiaceae | Bloebloomsalie (Afrikaans) | Not specified | A tincture is drunk to treat whooping cough. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Salvia chamdaeagnea Berg. | Lamiaceae | Bloublomsalie (Afrikaans) | Leaves and flowers | Used to treat whooping cough. Preparation and application method not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Salvia microphylla Kunth | Lamiaceae | Rooisalie, rooiblomsalie (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Infusions are drunk to treat bacterial pneumonia. | Hulley and Van Wyk2017 |

| Schinus molle L. | Anacardiaceae | Peruvian pepper (English), peperboom (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Used to treat bacterial pneumonia. Preparation and application not specified. | Hulley and Van Wyk2017 |

| Searsia lancea (L.f.) F.A. Barkley | Anacardiaceae | Makkaree, kareeboom (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Infusions are drunk to treat bacterial pneumonia. | Hulley and Van Wyk2017 |

| Securidaca longpedunculata Fresen. | Polygalaceae | Violet tree (English), krinkhout, rooipeultjie, seepbasboom (Afrikaans), mpesu (Venda), iphuphuma (Zulu) | Roots | A decoction is consumed by the Venda to treat TB. | Pallant and Steenkamp (2008) |

| Senecio serratuloides DC. | Asteraceae | Two-day cure (English), ichazampukane, insukumbili, umaphozisa umkhuthelo (Zulu) | Aerial parts | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Solanum nigrum L. | Solanaceae | Black nightshade (English) | Leaves | Fresh leaves are consumed to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Solanum retrofractum Vahl | Solanaceae | Nastergal, nasgal (Afrikaans) | Not specified | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Hulley and Van Wyk2017 |

| Spergula arvensis L. | Caryophyllaceae | Corn spurry (English) | Whole plant | An essential oil used to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Strophanthus grandiflorus (N.E.Br.) Gilg | Apocynaceae | Unknown | Whole plant | An alcohol extract is consumed to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Sutherlandia frutescens (L.) R.Br. | Fabaceae | Cancer bush (English), kankerbos (Afrikaans), ‘musa-pelo, motlepelo (Sotho), insiswa, unwele (Xhosa, Zulu) | Leaves | A decoction is used to treat TB. | Nortjie and Van Wyk (2015) |

| Syzygium cordatum Hochst. ex Krauss | Myrtaceae | Waterberry (English), waterbessie, waterboom (Afrikaans), undoni (Zulu), umswi, umjomi (Xhosa), mawthoo (Southern Sotho), motlho (Northern Sotho), mutu (Venda) | Leaves | Used by the Zulu to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962); Hutchings et al., (1996); Corrigan et al. (2011); |

| Syzygium gerrardii (Harv. ex Hook.f.) Burtt Davy | Myrtaceae | Unknown | Leaves | Used by the Zulu to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962); McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Tabernaemontana elegans Stapf | Apocynaceae | Toad tree (English), laeveldse paddaboom (Afrikaans), umKhahlwana, umKhadu (Zulu) | Leaves, roots | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Pallant and Steenkamp (2008); Dzoyem et al. (2016) |

| Taraxacum officinale (L.) Weber ex F.H.Wigg | Asteraceae | Dandelion (English) | Flowers, leaves, roots, whole plant | Used to treat TB. Extracts were consumed orally to treat tuberculosis. | Sharifi-Rad et al. (2018); Smith (1895); Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Terminalia phanerophlebia Engl. & Diels | Combretaceae | Lebombo cluster-leaf (English), lebombotrosblaar (Afrikaans), amaNgwe-amnyama, amaNgwe-omphofu (Zulu) | Roots | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Madikizela et al. (2013) |

| Terminalia sericea Burch. ex DC. | Combretaceae | Silver cluster leaf (English), vaalboom (Afrikaans), mususu (Venda) | Roots and leaves | Decoctions and infusions are consumed to treat bacterial pneumonia. | McGaw et al. (2008); Van Wyk et al. (2009); York et al. (2011); |

| Tetradenia riparia (Hochst.) Codd | Lamiaceae | Misty plume bush, ginger bush (English), gemerbos, watersalie (Afrikaans), iboza, ibozane (Zulu) | Leaves, roots | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Thesium hystrix A.W. Hill | Santalaceae | Kleinswartstorm (Afrikaans) | Root | Large volumes of a root decoction are drunk to treat TB. | Smith (1895),Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962); Van Wyk et al. (2009) |

| Thymus serpyllum L. | Lamiaceae | Breckland thyme, wild thyme, creeping thyme, elfin thyme (English) | Leaves and flowers | Used to treat whooping cough. Preparation and application methods are not specified. | Smith (1895); Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962); |

| Thymus vulgaris L. | Lamiaceae | German thyme, common thyme (English) | Leaves | Leaf essential oil is used to treat whooping cough. Application methods is not specified. | Smith (1895); Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962); McGaw et al. (2008); |

| Trachyandra laxa (N.E.Br.) Oberm. | Xanthorrhoeaceae | Unknown | Roots | Used to treat whooping cough. Preparation and application are not specified. | Von Koenen (2001) |

| Trema orientalis (L.) Blume | Cannabaceae | Pigeon wood (English), hophout (Afrikaans) | Leaves and fruit | Infusions of the leaves and fruit are drunk to treat bacterial pneumonia. | Von Koenen (2001) |

| Trichilia emetica Vahl | Meliaceae | Ixolo, umathunzini, umkhula (Zulu) | Leaves | Decoctions are used to treat pneumonia and whooping cough. | York et al. (2011) |

| Trifolium pratense L. | Fabaceae | Red clover (English) | Flowers | Infusions are drunk to treat TB and whooping cough. | Smith (1895); Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962); |

| Tulbaghia alliacea L.f. | Amaryllidaceae | Wild garlic, woodland garlic (English), wildeknoflok (Afrikaans), molela (Southern Sotho), ishaladilezinyoka, umwelela (Zulu) | Bulbs | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Smith (1895); Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962); Van Wyk (2008) |

| Tulbaghia maritima Vosa | Amaryllidaceae | Unknown | Bulbs | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Smith (1895); Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Tulbaghia violacea Harv. | Amaryllidaceae | Wild garlic (English), wilde knoffel (Afrikaans), isihaqa (Zulu) | Bulbs | Decoctions are drunk to treat TB. | Philander (2011); Smith (1895); Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962); Van Wyk et al. (2009) |

| Urtica urens L. | Urticaceae | Annual nettle, burning nettle, sting nettle bush, dwarf stinging nettle (English), brandnekel (Afrikaans) | Bark | Bark infusions are drunk to treat TB, pneumonia and whooping cough. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962); Van Wyk (2008); Hulley and Van Wyk2017 |

| Viscum capense L. f. | Santalaceae | Cape mistletoe (English), lidjiestee, voelent (Afrikaans) | Whole plant | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | Philander (2011) |

| Vitis vinifera L. | Vitaceae | Common grape (English) | Fruit | A syrup prepared by boiling the fruit juice is used in the Transvaal to treat diphtheria. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Warburgia salutaris (G.Bertol.) Chiov. | Canellaceae | Pepper-bark tree (English), peperbasboom (Afrikaans), mulanga, manaka (Venda), isibhaha (Zulu) | Bark | Used to treat TB. Preparation and application not specified. | McGaw et al. (2008) |

| Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal | Solanaceae | Indian ginseng, poison gooseberry, winter cherry (English), bitterappelliefie, koorshout (Afrikaans), ubuvuma (Xhosa), ubuvimbha (Zulu) | Root | Alcohol root extracts are drunk to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Zanthoxylum capensis (Thunb.) Harv. | Rutaceae | Knobwood (English) | Bark | The Zulu use a root bark decoction to treat TB. | Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk (1962) |

| Ziziphus mucronata Willd. | Rhamnaceae | Buffalo thorn (English), blinkblaar-wag-'n-bietjie (Afrikaans), umphafa, umlahlankosi, isilahla (Zulu), umphafa (Xhosa), mutshetshete (Venda), mokgalô, moonaona (Sotho) | Leaves, bark and roots | A decoction of the leaves, roots and bark is drunk to treat TB. | McGaw et al. (2008); Suliman (2010) |

The relatively high number of plant species used to treat bacterial respiratory diseases may relate to the seriousness and relative prevalence of these infections. Indeed, the vast majority of the plants recorded for use against bacterial respiratory infections were used against bacterial pneumonia (139 species) or TB (81 species). Both of these diseases are relatively common in southern Africa and produce relatively high mortality rates. It is therefore perhaps not surprising that high numbers of plant species were identified for the treatment of these diseases.

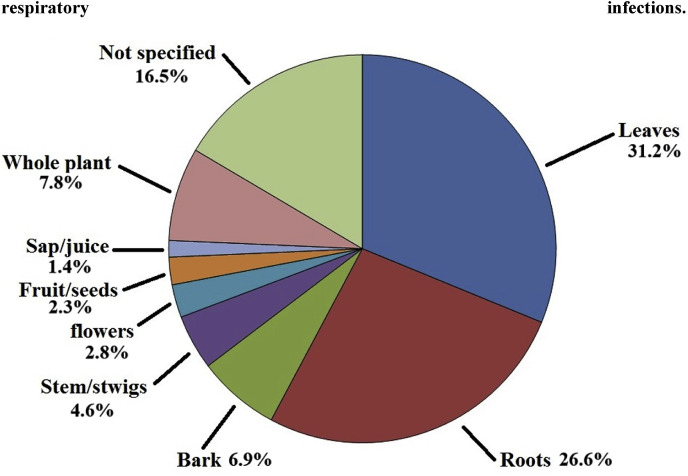

Many of the ethnobotanical books, reviews and primary studies used in this review did not specify the preparation of the traditional medicine or how it was used and further studies are required to clarify this. However, many of the recent ethnobotanical surveys did report these details, further emphasising the importance of updated ethnobotanical information. From those studies, a further trend was also evident: decoctions and infusions were most widely used in the treatment of bacterial respiratory infections, with 64 plant-based medicines reported to be used in these ways. Previous studies have also reported that decoctions and infusions are the most common methods for treating most pathogenic diseases (Afolayan et al., 2014; Asong et al., 2019; Cock et al., 2018; Cock et al., 2019; De Beer and Van Wyk, 2011; Hulley and Van Wyk, 2017; Nortje and Van Wyk, 2011; Philander, 2011). Tinctures were prepared and consumed for a further four species, volatiles targeted from three species via inhalation, and a syrup was prepared and consumed from the fruit of various species. This contrasts dramatically with the preparation and usage of plant species to treat viral respiratory diseases, where inhalation was the main method of administration (unpublished results). The use of southern African plants to treat viral respiratory plants will be the basis of another manuscript in preparation.

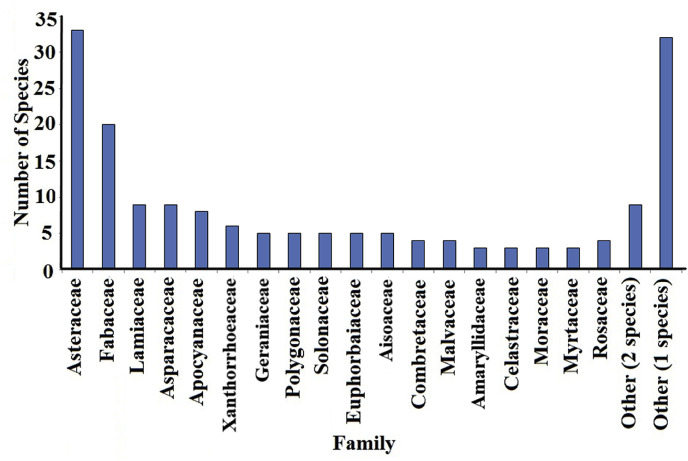

A wide variety of families of southern African plant species including Apiaceae, Asparagaceae, Asphodelaceae, Apocynaceae, Asteraceae, Brassicaceae, Celastraceae, Combretaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, Lauraceae, Malvaceae, Moraceae, Myrtaceae, Polygonaceae, Rosaceae and Solanaceae (Fig. 1 ) were traditionally used to treat bacterial respiratory diseases. Although the bioactivity of several of these species has already been screened against bacterial respiratory pathogens via in vitro testing (Table 2 ), most species are yet to be screened against respiratory bacterial pathogens. Asteraceae (33 species) and Fabaceae (20 species) were commonly used traditionally to treat bacterial respiratory diseases (Fig. 1). Lamiaceae (9 species), Asparagaceae (9 species), Apocynaceae (8 species), Xanthorrhoeaceae (6 species), Aisoaceae, Geraniaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Polygonaceae and Solanaceae were also well represented with 5 species each. Four members of Combretaceae, and Malvaceae were also identified, as well as three members each of Amaryllidaceae, Celastraceae, Moraceae, Myrtaceae and Rosaceae. Two or less species of fourty-one other families were also identified as being traditionally used to treat bacterial respiratory diseases.

Fig. 1.

The number of southern African plant species per family related to southern African medicinal plants for the treatment of bacterial respiratory infections. Others refers to the number of other genuses (not named individually) that are represented by the indicated number of species.

Table 2.