Abstract

Background: Vaginal calculi are rare and can grow quite large if they remain undetected. Vaginal stones are caused by the pooling of urine in the vagina and can be classified as either primary or secondary, depending on the absence or presence, respectively, of a nidus. Primary stones without any urethrovaginal or vesicovaginal fistula are even more uncommon but appear to be more commonly reported in incontinent women with significant physical disabilities.

Case Presentation: We present a case of an ∼11 cm primary vaginal stone in a 61-year-old woman with cerebral palsy. This was removed using a nephroscope and an endoscopic ultrasonic lithotrite through the vaginal introitus with subsequent analysis demonstrating a struvite stone composition.

Conclusion: This case is unique not only for the large size of the calculi but also for our less invasive approach, using a nephroscope and endoscopic ultrasonic lithotrite to fragment and remove the stone. We hope that this report will assist other providers in the timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment of future vaginal stone patients.

Keywords: urolithiasis, instrumentation, vaginal stone, nephroscope

Introduction/Background

Vaginal stones are rare occurrences with the majority of stones forming as secondary stones around a foreign body. These stones can also form because of urinary stasis in patients with a urethrovaginal or vesicovaginal fistula or because of long-standing incontinence causing pooling of urine in the vagina, the latter being a rarer occurrence previously reported in a small number of case reports.1–3

Case Presentation

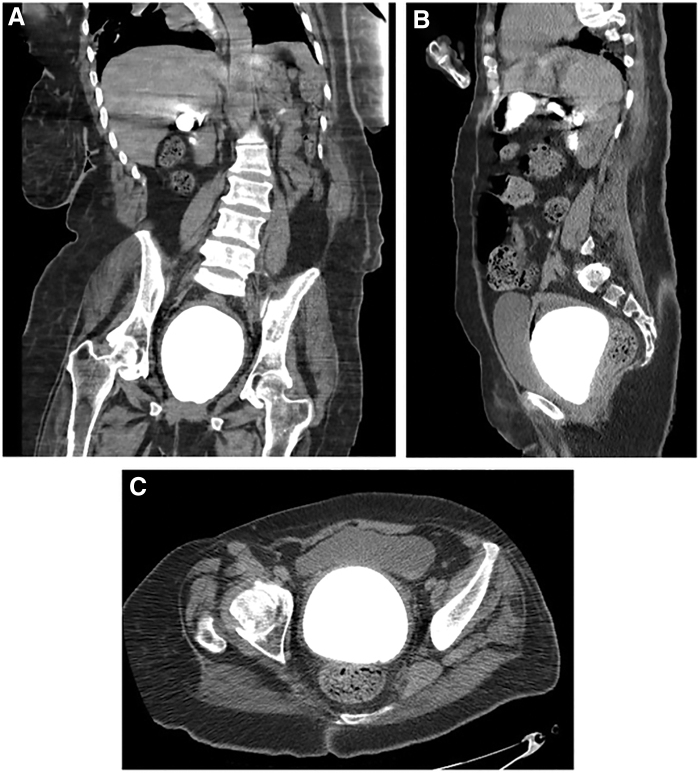

A 61-year-old postmenopausal woman with a past medical history significant for global neurologic deficits and cerebral palsy after a cerebrovascular accident at the age of 15 years was evaluated at an outside hospital because of an episode of vaginal bleeding. Since the time of her cerebrovascular accident, the patient has been bed bound and incontinent to both feces and urine, voiding into a diaper and requiring 24-hour care. Pelvic examination revealed a foreign body within the vagina with a pumice-like texture. It should be noted that the initial pelvic examination was extremely difficult secondary to the patient's habitus and an atrophic introitus. Because of severe lower extremity contractures her legs could only be separated a few inches. Initial plain kidney, ureter, and bladder radiograph demonstrated a large radiodense calculus in the pelvis (Fig. 1). Subsequent CT confirmed an 11 × 9 × 8 cm laminated calcification in the vaginal cavity (Fig. 2). The patient was transferred to our institution for tertiary multidisciplinary care.

FIG. 1.

Plain kidney, ureter, and bladder radiograph of the abdomen and pelvis showing a large radio-opaque calculus.

FIG. 2.

CT imaging showing calcified mass in coronal, sagittal, and axial views (A–C).

A subsequent MRI was performed to rule out a vesicovaginal fistula. MRI imaging revealed a nonenhancing intraluminal mass with smooth contour measuring 10.6 × 8.6 × 8.8 cm without any evidence of a fistula (Fig. 3). A thickened endometrial stripe and a possible polyp were also noted.

FIG. 3.

MRI showing T1 and T2 sagittal (A, B) and T1 axial views (C) of the vaginal stone.

A thorough discussion was had with the patient's family. Consent was obtained for endoscopic lithotripsy and removal of the stone as well as an endometrial biopsy. Given the size of the stone and the patient's severe lower body contractures, the family was made aware that a more significant procedure, specifically an abdominal hysterectomy, may be necessary at a later date if the endoscopic removal was not effective. The patient was subsequently taken to the operating room. Under general anesthesia the patient was placed in a partial dorsal lithotomy position (Fig. 4). A 16F Foley was inserted to drain the bladder. A 23F rigid nephroscope was inserted into the vaginal introitus and an endoscopic ultrasonic lithotrite, the Olympus ShockPulse, was employed to pulverize and vacuum the stone. Physiologic saline was used for irrigation. The procedure was complex given the density, large size, and location of a portion behind the pubic symphysis but was effective in breaking up the stone into fragments that could then be extracted using a ring forcep and tenaculum (Fig. 5). Once the stone removal was complete an endometrial biopsy was performed to rule out an endometrial biopsy given the thickened endometrial stripe on preoperative imaging.

FIG. 4.

Patient positioning in the operating room.

FIG. 5.

Endoscopic view during fragmentation and stone fragments.

Inspection of the vaginal tissue after removal of the stone did not reveal any lacerations residual stone, or evidence of fistula. Cystoscopy during and at the conclusion of the procedure was unremarkable. Postoperative imaging was not obtained given the extensive examination poststone removal, which was unremarkable. Stone composition analysis showed 60% magnesium ammonium phosphate (struvite) and 40% calcium phosphate (apatite). Pathology analysis of the endometrial biopsy demonstrated inactive endometrium, lymphocytic, and plasma cell infiltrates consistent with chronic endometritis. The patient's postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged after observation overnight.

Discussion and Literature Review

Vaginal stones are often classified according to etiology, with primary stones forming secondary to urinary stasis within the vaginal cavity and secondary stones forming around a foreign body. Most primary stones form secondary to a vesicovaginal or urethrovaginal fistula but can also occur because of urinary incontinence, which was likely the cause in this case. Secondary stones have also been observed in cases of surgical mesh placement or intrauterine devices.

Vaginal stones may go undiagnosed for some time given their likelihood of forming in patients with physical and mental disabilities, especially patients bedridden for long periods of time.1–3 These patients might not be able to verbalize complaints such as abdominal pain and in this case the calculus was only diagnosed after an episode of vaginal bleeding caused by the stone. The size of the stone in this case was most likely because of the prolonged course of urinary and fecal incontinence in this patient, who was bedridden for >45 years before this presentation. Interestingly, we did not find postmenopausal vaginal bleeding as an initial presenting sign in any previous reports, with similar cases in nonverbal disabled adults presenting as infection1,3 or diagnosis after CT for suspected enlarging bladder stone.2

Based on our review of the available literature, we believe this may be the largest reported vaginal stone at 10.6 × 8.6 × 8.8 cm. Previously published case reports have noted primary vaginal stones as large as 10 × 8 × 4.5 cm.3 Given the size of this calculus, the initial management discussion of this patient was centered around abdominal hysterectomy or vaginal removal after episiotomy, both procedures that carry significant morbidity for complex disabled patients. In light of these concerns, we opted for a less invasive approach using a nephroscope and endoscopic ultrasonic lithotrite, instruments normally used in the treatment of renal calculi during percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Based on our review of the literature this may be the first reported use of a nephroscope in an adult with a vaginal stone, with only a single previous pediatric case report for a vaginal stone.4 This approach allowed for effective removal without requiring an episiotomy and was performed without any laceration to the vaginal mucosa.

The struvite composition of the stone likely reflects bacterial infection and subsequent alkalinization of the urine by urease producing bacteria such as Proteus mirabilis, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella spp. This infectious process was likely assisted by the concomitant fecal incontinence in this patient, and based on previous literature this appears to be the most common composition of primary vaginal stones.1

Conclusion

Although vaginal stones are a rare diagnosis, they should be considered as a potential complication for individuals with disabilities, urinary incontinence, and long-term recumbent positioning. There were several unique aspects of our case that add to the literature, including the presentation of postmenopausal bleeding, the large size of the calculus, and our removal using a nephroscope to minimize the morbidity of the procedure. Although these stones are rare, we hope that this report may assist other providers in the timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment of future vaginal stone patients.

Abbreviations Used

- CT

computed tomography

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Cite this article as: Fedrigon III D, Bretschneider CE, Muncey W, Stern K (2020) Removal of large primary vaginal calculus using the nephroscope and endoscopic ultrasonic lithotrite: a case report, Journal of Endourology Case Reports 6:2, 92–95, DOI: 10.1089/cren.2019.0099.

References

- 1. De Francesco P, Nicolai M, Castellan P, et al. Primary vaginal calculus in a woman with disability: Case report and literature review. J Endourol Case Reports 2017;3:182–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ikeda Y, Oda K, Matsuzawa N, Shimizu K. Primary vaginal calculus in a middle-aged woman with mental and physical disabilities. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24:1229–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lin CJ, Hsu HH, Chen CP, Wu CH, Chen HY. Huge primary vaginal stone in a recumbent woman. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2005;44:80–82 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jaspers JW, Kuppens SM, van Zundert AA, de Wildt MJ. Vaginal stones in a 5-year-old girl: A novel approach of removal. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2010;23:e23–e25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]