Abstract

Background: Ureteroarterial fistula (UAF) is a rare and potentially devastating diagnosis most often associated with a combination of pelvic oncologic or vascular surgery, radiation, and chronic ureteral stents. Herein we discuss a patient with an ileal conduit urinary diversion and left nephroureteral (NU) catheter who presented with gross hematuria and hemodynamic instability. He underwent multiple negative radiologic investigations and his clinical course highlights the need for a high index of suspicion for UAF and multidisciplinary coordination with vascular surgery and interventional radiology.

Case Presentation: Our patient is a 64-year-old male with a history of bladder cancer and atrial fibrillation on rivaroxiban who underwent cystoprostatectomy with ileal conduit urinary diversion. His postoperative course was complicated by subsequent mid-distal stricture of his left ureter, which was managed with balloon dilatation and a chronic indwelling NU catheter. He underwent a routine catheter exchange ∼1 year postradical cystectomy and subsequently experienced intermittent gross hematuria. He presented 5 weeks later with profound hematuria and clots through his urostomy accompanied by flank pain, weakness, and tachycardia. Throughout his hospital course he underwent two CT angiograms and a formal provocative angiogram that were all negative. He was taken to the operating room (OR) for attempted antegrade ureteroscopy, which was aborted because of pulsatile bleeding observed upon withdrawal of his stent. In collaboration with vascular surgery, he was eventually taken for provocative angiogram and covered stent graft placement that resolved the hematuria.

Conclusion: This case highlights the diagnostic and care coordination challenges in patients with UAF. A high suspicion should be maintained in patients with hematuria and indwelling stents with a history of pelvic surgery and/or radiation.

Keywords: ureteroarterial fistula, ureteroiliac fistula, ileal conduit, ureteral stent, urinary diversion

Introduction and Background

Ureteroarterial fistula (UAF) is an uncommon occurrence often associated with pelvic oncologic or vascular surgery, radiation, and indwelling ureteral stents. There are ∼150 total cases of UAF reported with mortality rates ranging from 10% to 20%.1 Hematuria is invariably present and may be accompanied by hydronephrosis, flank pain, and hemodynamic instability. The most sensitive diagnostic tool of choice is angiography with provocative maneuvers to dislodge any clot in the ureter obscuring the fistulous tract.2 In the majority of patients, the UAF is located at the crossing of the ureter over the common iliac artery with ∼20% presenting at the external iliac artery.1 Traditionally, open repair was the gold standard but with modern endovascular techniques, placement of a covered vascular stent is the treatment of choice.

Presentation of Case

The patient is a 64-year-old male with a medical history significant for coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction and cardiac stents, obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation on rivaroxiban. He was found to have recurrent multifocal high grade Ta urothelial carcinoma and urothelial carcinoma in situ of the bladder that was refractory to induction intravesicle bacillus Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy as well as intravesicle Valrubicin. He subsequently underwent robot-assisted cystoprostatectomy with ileal conduit diversion. Final pathology report revealed high-grade urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, stage pTaN0Mx with negative margins.

His postoperative course was complicated by small bowel obstruction managed by exploratory laparotomy with small bowel resection. He subsequently developed urine leak that was managed with bilateral percutaneous nephrostomy tube (NT) placement. He then developed a left distal ureteral stricture that was managed with percutaneous nephroureteral (NU) catheter. Ileal conduit revision was recommended; however, he elected chronic NU tube. The first NU exchange was complicated by obliterative strictures at the mid and distal left ureter. He underwent balloon dilatation and his next two NU catheter exchanges proceeded without complication.

One month after the last NU catheter exchange, he presented to the emergency department with hematuria from his NU and frank clots from his ileal conduit. His hematuria was accompanied by left flank pain and acute kidney injury. Overnight, he developed worsening abdominal and left flank pain and hemodynamic instability. He received 4 U of blood and rivaroxiban was reversed with FEIBA (Anti-Inhibitor Coagulant Complex). Interventional radiology (IR) was immediately consulted and recommended triple phase CT angiogram (CTA), which unfortunately did not localize the source of hematuria. Over the course of the following hospital day, he suffered an anterior myocardial infarction with preserved left ventricular function which was managed conservatively. His hematuria quickly resolved with supportive management.

However, the evening before planned discharge, he again experienced brisk bleeding from his ileal conduit after straining for a bowel movement. He was emergently taken to the IR suite and an angiogram was performed. Of note, upon review of the patient's last negative CTA with the urologic and IR teams, there appeared to be fibrotic inflammation at the point of crossing of the left ureter and left common iliac artery (Fig. 1). The NU catheter was slowly removed as a provocative maneuver to unmask what was suspected at this time to be a UAF. Despite removal of the stent and full fluoroscopic interrogation of the distal aorta (pelvic), left common iliac, left renal, and superior mesenteric arteries, no source of the hematuria was demonstrated. Subsequent concurrent nephrostogram revealed no ureteral irregularities.

FIG. 1.

Arterial phase of CT angiogram shown from cephalad to caudad at the crossing of the left stented ureter and left common iliac artery. No extravasation of contrast was seen; however, there is evidence of periarterial and ureteral inflammation as denoted by the arrow.

He stabilized with supportive measures but still experienced intermittent hematuria and was taken to the OR for attempted antegrade ureteroscopy. However, immediately upon withdrawal of the NU catheter, brisk pulsatile bleeding was noted both from his nephrostomy tract and through the ileal conduit, which ceased upon readvancement of the catheter. Antegrade ureteroscopy was abandoned and nephrograms were not taken because of his hemodynamic instability. However, fluoroscopic images were able to be captured at the point at which the bleeding stopped upon manipulation of the NU catheter (Fig. 2). From these images, it was inferred that the origin of bleeding was approximately at the level of the iliac vessels, confirming our suspicion of UAF. A vascular surgery consultation was obtained and surgical exploration was considered; however, the patient refused major surgical intervention. Another CTA was obtained that did not reveal any source of hemorrhage.

FIG. 2.

Fluoroscopic image obtained in the operating room during nephroureteral catheter exchange and attempted antegrade ureteroscopy. The arrow denotes the position of the NU catheter at the moment of tamponade of arterial bleeding during catheter advancement, providing a rough estimate of the level of the fistula. NU, nephroureteral.

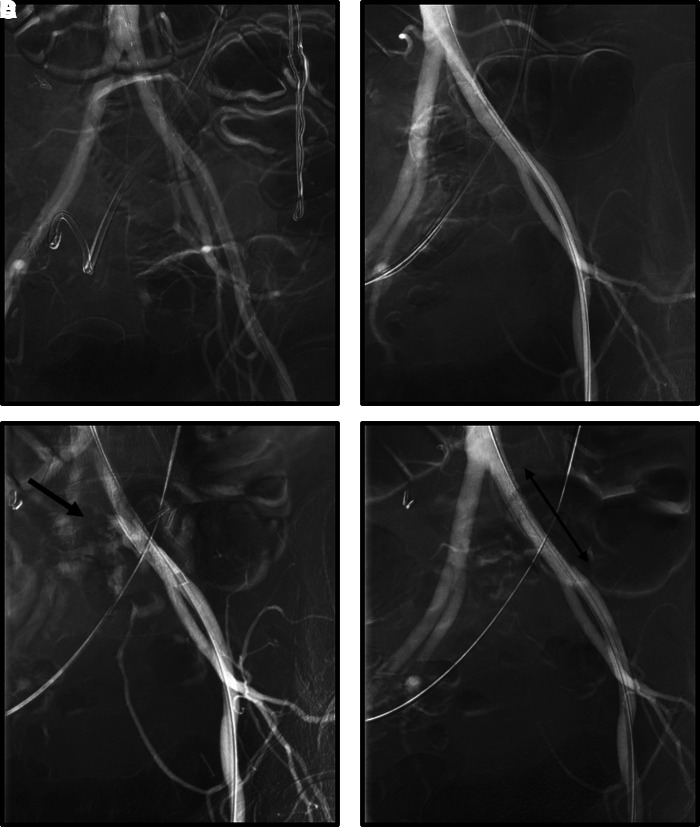

In the days following, it was decided to take the patient to the OR by both vascular surgery and urology for provocative angiogram and possible iliac artery stent placement based on the ongoing clinical scenario. In the angiography suite, once vascular and urinary access were secured, the NU catheter was withdrawn slowly to attempt to provoke bleeding. After a short delay, pulsatile bleeding was again noted from both the nephrostomy tract and ileal conduit. An angiogram performed at this time was positive for fistulous connection between the left ureter and the left common iliac artery (Fig. 3). The vascular surgery team deployed a LifeStream covered stent (Bard, Tempe, AZ) once the location of the bleed was delineated. Deployment of the vascular stent to the common iliac artery immediately halted the urinary tract bleeding. The NU catheter was exchanged for an NT by the urology team. The patient did well postoperatively and made a slow but steady recovery with no recurrent hemorrhagic events.

FIG. 3.

Fluoroscopic images obtained during endovascular stent graft placement. (A) Initial image with nephroureteral catheter still in place. (B) Antegrade access was obtained through the nephroureteral catheter and vascular access from the left femoral groin before provocative maneuvers. (C) Arrow denotes the arterial blush observed at left common iliac upon the removal of the nephroureteral catheter. Pulsatile bleeding was seen from the nephrostomy tract and ileal conduit at this time. (D) Resolution of arterial blush after placement of covered iliac stent. The proximal and distal ends of the vascular stent are marked by the double-headed arrow.

Discussion and Literature Review

UAF tracts are thought to arise from pressure necrosis induced by continuous pulsatile flow of the iliac artery against a stented ureter in the setting of fibrotic inflammation. The majority of patients have a history of pelvic surgery for oncologic or vascular etiologies and most have a history of pelvic radiation. Hematuria is the rule though it may be microscopic or associated with urinary infections, obscuring the diagnosis of fistula. Although UAF is uncommon, the mortality rate is 10% to 20% and increased in cases wherein the diagnosis was not suspected preoperatively.1

The gold standard of definitive management is open repair of the fistula. However, endovascular placement of a stent graft is more common in the current era.3 Open surgery in this patient population is often difficult given a hostile surgical field and hemodynamic instability. Endovascular techniques have shown to be safe and as effective as open repair.3 Complications after treatment include graft infection, lower extremity morbidity, and recurrent hemorrhage.

Unfortunately, radiologic tests are not always definitive in diagnosing UAF because of the intermittent nature of the hemorrhage and potentially small fistulous tract. CTA has a reported sensitivity of ∼38% to 50% and ureteral contrast studies reported a sensitivity of 45% to 60%.4 Sensitivity can be greatly increased up to 60%–100% by provocative maneuvers (i.e., removal of the urinary stent in a controlled environment).4

In cases such as ours wherein a demonstrable fistulous tract cannot be demonstrated on imaging despite provocative maneuvers, collaboration between vascular surgery and urology is imperative to thoroughly interrogate the patient's anatomy based on a high level of clinical suspicion. Despite timely procurement of imaging studies, several false negative series were obtained in the absence of brisk bleeding in our patient because of the tamponade provided by the NU catheter. It is unusual that our initial provocative angiogram was negative as patients generally will exhibit hemorrhage when the tamponading stent is removed. However, in some cases, the presentation may be more subtle or intermittent because of clot formation over the fistula tract. This is supported by each of this patient's hemorrhagic episodes being triggered by Valsava maneuvers. However, there were several subtle positive findings such as the area of fibrosis seen on the original negative CTA and fluoroscopic images taken in the OR using the tip of the NU stent as a marker to pinpoint the origin of bleeding.

In scenarios where the clinical suspicion is high, the case should be discussed among all involved teams (urology, vascular surgery, and IR when appropriate). A decision to proceed to the OR may be made without definitive imaging. It is also safest to perform provocative maneuvers in a controlled environment with both urinary and vascular access assured beforehand. Furthermore, in cases with intermittent hematuria, careful examination of events immediately preceding hemorrhagic episodes should be performed and may assist in guiding provocative maneuvers in the OR.

Our patient's history of cystectomy and chronic and difficult ureteral stent exchanges with recurrent severe hemorrhage and soft radiologic signs of potential fistulous tract led to the diagnosis of UAF. This particular case highlights the diagnostic challenge inherent in these cases as our patient was too unstable to perform urologic interrogation alone but also too difficult to catch during an active bleed for CT angiography while his NU catheter was in place.

Conclusion

UAFs are uncommon and thus may present a diagnostic challenge. However, in the setting of indwelling urinary stents and hematuria, if the patient has a history of pelvic malignancy, surgery, or radiation, a high level of suspicion must be sustained to prevent mortality. Communication among interventional radiology, vascular surgery, and urology is critical for expeditious care and appropriate work-up. It is common to have negative imaging, and multidisciplinary care must be conducted based on clinical suspicion.

Abbreviations Used

- CT

computed tomography

- CTA

CT angiogram

- IR

interventional radiology

- NT

nephrostomy tube

- NU

nephroureteral

- UAF

ureteroarterial fistula

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Cite this article as: Crane A, Rizzo A, Gong M, Sivalingam S (2019) Ureteroarterial fistula in a patient with an ileal conduit and chronic nephroureteral catheter, Journal of Endourology Case Reports 5:2, 64–67, DOI: 10.1089/cren.2019.0004.

References

- 1. Subiela JD, Balla A, Bollo J, et al. Endovascular management of ureteroarterial fistula: Single institution experience and systematic literature review. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2018;52:275–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van der Bergh, Moll FL, de Vries JP, et al. Arterioureteral fistulas: Unusual suspects–systematic review of 139 cases. Urology 2009;74:251–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fox JA, Krambeck A, McPhail EF, et al. Ureteroarterial fistula treatment with open surgery versus endovascular management: Long-term outcomes. J Urol 2011;185:945–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lara-Hernandez R, Riera Vazquez R, Benabarre Castany N, et al. Ureteroarterial fistulas: Diagnosis, management, and clinical evolution. Ann Vasc Surg 2017;44:459–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]