Abstract

Reactions of SiCl4 with R2PO(OH) (R=Me, Cl) yield compounds with six‐fold coordinated silicon atoms. Whereas R=Me afforded the hexacoordinated tetra‐cationic silicon complex [Si(Me2PO(OH))6]4+ with chloride counter‐ions, R=Cl caused release of HCl with formation of a cyclic dimeric silicon complex [Si(Cl2PO(OH))(Cl2PO2)3(μ‐Cl2PO2)]2 with bridging bidentate dichlorophosphates.

Keywords: hypervalent compounds, NMR spectroscopy, Si−Cl dissociation, structure elucidation, X-ray diffraction

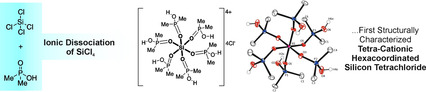

Ionic dissociation of SiCl4: The first example of a structurally characterized tetra‐cationic hexacoordinated silicon tetrachloride is reported. It was obtained by reaction of dimethylphosphinic acid with SiCl4 under ambient conditions. Additionally, the structure of a cyclic dimeric hexacoordinated silicon complex was determined by single‐crystal X‐ray diffraction and verified by solid‐state NMR spectroscopy.

Design of hypercoordinated silicon compounds is of particular interest in organic chemistry, where they may play roles as catalysts and reagents.1, 2 As heavier congener of carbon, silicon and its higher coordination number compounds are of particular academic interest as well. Thus, various neutral, anionic and cationic silicon complexes have been reported.3, 4 A more specific topic are hexacoordinated silicon compounds with [SiO6] skeletons. In naturally occurring low‐pressure silicates5 and silicophosphate minerals6 the silicon atom is present in fourfold coordination. Only several high‐pressure silicates, for example, stishovite or MgSiO3 5 and synthesized (at atmospheric pressure) crystalline silicophosphate compounds, for example, SiP2O7 7 or Si5O(PO4)6 8 contain hexacoordinated silicon atoms. Molecular silicon compounds with [SiO6] skeletons include besides anionic species, like the dianions of [SiVI(PO4)6(SiIV(OEt)2)6],9 [SiVI(S2O7)3]10, 11 or [SiVI(P3O9)2],12 also neutral complexes13 and cationic complexes. The latter include mainly monocationic species14 while some tetracationic complexes are known in literature only for systems with very soft (“silicophobic”) counter‐ions, for example, hexa(pyridine‐N‐oxide)silicon tetraiodide ([Si(pyO)6]I4)15 or hexakis(N,N‐dimethylformamide)silicon tetraiodide ([Si(DMF)6]I4).16 As to neutral O‐donor ligands, hypercoordinated adducts of SiF4 with phosphine oxides, trans‐[SiF4(OPPh3)2],17 and of SiCl4 with phosphoric amides, for example, [Cl3Si(OP(NMe2))3]‐cation,18 are also known, while OH‐functionalized P=O‐compounds tend to act as anionic ligands.

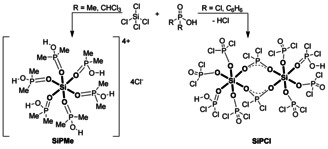

In this regard, dichlorophosphates ([Cl2PO2]−) are described as bridging bidentate ligands through the coordination of both oxygens to metal atoms. Additionally, dichlorophosphate can operate as monofunctional and also as trifunctional group.19 In trimethylsilyl dichlorophosphate, Cl2PO2SiMe3, only one oxygen is coordinated to silicon because of the poor hypercoordination tendency of SiMe3 groups.19, 20 Dimethylphosphinate groups ([Me2PO2]−) were also handled as bridging bidentate ligands.21, 22, 23 Here, we report the crystal structures of the two different six‐fold coordinated silicon compounds SiPCl and SiPMe (Scheme 1), which enhance the portfolio of coordination motifs. The complexes were prepared by reaction of SiCl4 with dichlorophosphoric acid in benzene (SiPCl) and dimethylphosphinic acid in chloroform (SiPMe) (see Supporting Information for details).

Scheme 1.

Preparation of the hexacoordinated silicon compounds SiPMe and SiPCl ([SiO6]‐structural units are bold indicated for clarity).

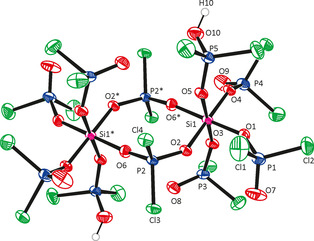

Figure 1 shows the molecular structure of SiPCl in the crystal (triclinic, space group P‐1). A compound of this formal composition “H[Si(O2PCl2)5]” has been reported in literature (also obtained by the reaction of dichlorophosphoric acid and SiCl4 in benzene),24 but its structure has not been elucidated so far. Compound SiPCl is a cyclic dimer, which is located about a center of inversion. Two bridging Cl2PO2 ligands between two silicon atoms furnish a Si2O4P2 eight‐membered ring. The remaining four coordination sites at each of the octahedrally coordinated Si atoms host monodentate O‐donor ligands, that is, three Cl2PO2 − anions and one (HO)OPCl2 molecule. Thus, the molecule bears five crystallographically non‐equivalent dichlorophosphate groups. The silicon coordination spheres are slightly distorted octahedra with bond lengths and trans‐O‐Si‐O angle ranges of 1.73–1.79 Å and 175.6–178.4°, respectively. The Si−O bond lengths increase in the order monodentate anionic < bridging anionic < mono‐dentate neutral ligand (O1 and O5 share roles of anionic and neutral ligand as their Cl2PO2 moieties are intermolecularly connected by hydrogen bridges (i.e., O10−H10 is directed toward O7* of an adjacent molecule, O7* generated from O7 by symmetry operation x‐1, y, z)). The intermolecular separation O10−O7* (2.48 Å) is in accord with a highly attractive hydrogen bridge, but disorder of the P1O7Cl1Cl2 group hampers any detailed discussion of this hydrogen bridge. The P−O distances range from 1.45 Å (normal double bond lengths) to 1.53 Å and the angles about phosphorus span a range of 105–114° with angles increasing in the order Cl‐P‐Cl<Cl‐P‐O<O‐P‐O (in accordance with VSEPR). P−Cl and P−O distances in SiPCl do not differ significantly from corresponding distances in POCl3 (P−Cl: 1.98 Å, P=O: 1.45 Å)25 or other related compounds with Cl2PO2 ligands, for example, [(Cl3SnOPCl3)+(PO2Cl2)−]2 (P−Cl: 1.98 Å, P−O: 1.50 Å).26

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of SiPCl in the crystal. (ORTEP representation with 50 % probability ellipsoids). The P1O7Cl1Cl2 group was disordered and refined in two positions (site occupancy ratio 0.81(2):0.19(2)). Selected bond lengths and angles are provided in Table 1.

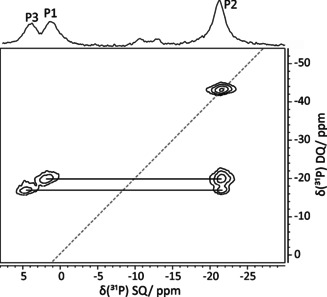

29Si and 31P solid‐state NMR spectroscopy points out few impurities from dichlorophosphoric acid and its (silylated) condensation products in the bulk solid material. Nevertheless, we were able to assign the 29Si chemical shift (−214.5 ppm) to the [Si(OP)6] octahedra and the 31P NMR signals to the phosphorous atoms of the crystal structure SiPCl (δ(31P)=1.8 ppm (P1), −21.5 ppm (P2), 4.5 ppm (P3), −10.4 ppm (P4), 15.1 ppm (P5)). The combination of 31P single pulse (SP), cross polarization (CP) and 31P double quantum (DQ)/single quantum (SQ) MAS NMR spectra allows the complete assignment of the 31P chemical shifts. The latter spectrum is given in Figure 2. We observe one diagonal DQ peak at −21.5 ppm (for the spatially closest chemically equivalent atoms P2) and furthermore, two DQ peak pairs at 1.8 ppm and −21.5 ppm (P1‐P2) as well as at 4.5 ppm and −21.5 ppm (P3−P2). A detailed explanation of the NMR analysis and the assignment is given in Supporting Information.

Figure 2.

31P DQ‐SQ‐MAS‐NMR spectrum of SiPCl.

Following our studies, we changed the phosphorus compound from dichlorophosphoric acid to dimethylphosphinic acid. Dimethylphosphinate groups [(Me2PO2]−) were also reported as bridging bidentate ligands.21, 22, 23 Known structures with dimethylphosphinate groups, for example, Et2Sn(O2PMe2)2,21 Me3SnO2PMe2 22 and Et2ClSnO2PMe2 23 are polymeric, whereas Ph2Sn(O2PMe2)2 has a polymeric ring‐chain structure. The Me2PO2 ligands functioning as double bridges, like in SiPCl, between tin atoms to give eight‐membered Sn2O4P2 rings.21 Here, we can report a new crystalline product based on dimethylphosphinic acid as a neutral oxygen‐donor ligand, which was obtained by the reaction of tetrachlorosilane with dimethylphosphinic acid in chloroform.

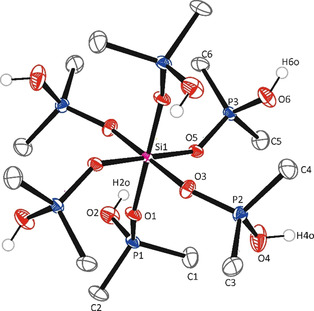

Contrary to our expectation (i.e., substitution with release of HCl), a novel tetra‐cationic silicon complex was created by ionic dissociation of SiCl4, because the dimethylphosphinic acid (pK=3.1)27 is a weaker acid than for example, methylphosphonic acid (pK=2.3)27 or methylphosphoric acid (pK=1.5).25 In contrast the dichlorophosphoric acid is described as a strong acid, which forces weaker acids out of its salts, for example, HCl from CaCl2.28 The formula composition in the crystal structure of compound SiPMe (monoclinic, space group C2/c, Figure 3) comprises of a [Si(Me2PO(OH))6]4+ cation, four chloride ions and one chloroform molecule. The Si atom is located on a crystallographic center of inversion, thus the asymmetric unit contains a half cation, two Cl anions and half a molecule CHCl3. The silicon atom of SiPMe is surrounded by the dimethylphosphinic acid molecules as neutral ligands in a nearly regular octahedral geometry with an average Si−O bond length of 1.76 Å (Table 1). The P−O distances range from 1.52 to 1.55 Å and are in good agreement with normal single bond lengths. One of the Cl anions in the asymmetric unit is hydrogen bonded to the OH groups of two neighboring cations. The other one is hydrogen bonded to only one cation. The H⋅⋅⋅Cl separations of these hydrogen bonds are around 2.1 Å. Additionally, Cl3CH⋅⋅⋅Cl (2.7 Å) and PCH3⋅⋅⋅Cl (2.9 Å) contacts were also found. Only a few other tetra‐cationic silicon compounds with neutral ligands were reported in literature, for example, hexa(pyridine‐N‐oxide)silicon tetraiodide, [Si(pyO)6]I4,15 hexakis(N,N‐dimethylformamide)silicon tetraiodide, [Si(DMF)6]I4,16 hexakis(N,N‐dimethylformamide)‐silicon tris(tribromide) chloride, [Si(DMF)6][Br3]3Cl29 and complexes with six N‐donor atoms.30, 31 The compound SiPMe is insoluble in organic solvents, so the 29Si and 31P NMR chemical shifts (δ(29Si)=−204.2 ppm; δ(31P)=56.88 ppm) were obtained from solid state NMR experiments.

Figure 3.

Molecular structure of SiPMe. (ORTEP representation with 50 % probability ellipsoids; C‐bonded hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity). The crystal structure is built up from [Si(Me2PO(OH))6]4+‐cations with four chloride ions and one molecule chloroform. Selected bond lengths and angles are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°] for SiPCl and SiPMe.

|

Bond lengths [Å] |

Angles [°] |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

SiPCl | |||

|

Si1−O1 |

1.770(2) |

O3‐Si1‐O5 |

178.42(10) |

|

Si1−O2 |

1.763(2) |

O4‐Si1‐O2 |

175.64(10) |

|

Si1−O3 |

1.730(2) |

O2‐Si1‐O5 |

87.87(9) |

|

Si1−O4 |

1.736(2) |

O6‐P2‐O2 |

114.06(11) |

|

Si1−O5 |

1.790(2) |

O2‐P2‐Cl4 |

108.57(8) |

|

Si1−O6 |

1.773(2) |

Cl3‐P2‐Cl4 |

105.98(4) |

|

SiPMe | |||

|

Si1−O1 |

1.7505(11) |

O1‐Si1‐O3 |

89.14(6) |

|

Si1−O3 |

1.7648(11) |

O1‐Si1‐O5 |

89.77(5) |

|

Si1−O5 |

1.7710(11) |

O3‐Si1‐O5 |

90.97(5) |

|

P3−O5 |

1.5230(11) |

O5‐P3‐O6 |

107.99(7) |

|

P3−O6 |

1.5543(13) |

O5‐P3‐C6 |

113.32(8) |

|

|

|

O6‐P3‐C6 |

110.10(9) |

|

|

|

O5‐P3‐C5 |

107.65(8) |

|

|

|

O6‐P3‐C5 |

108.79(9) |

|

|

|

C6‐P3‐C5 |

108.88(9) |

In order to probe whether the weaker Si−Br bond dissociates in a related manner, SiBr4 was treated with dimethylphosphinic acid, too. In fact, the corresponding bromide salt SiPMeBr formed, which shows very similar 29Si and 31P NMR signals and crystallizes as an isomorph of SiPMe (with longer unit cell axes because of the larger halide anion). Thus, a comparison of the corresponding data of SiPMe and SiPMeBr is given in the Supporting Information. The chemistry related to compound SiPMe is subject of ongoing investigations, because SiPMe is the first example of a structurally characterized tetra‐cationic hexacoordinated silicon tetrachloride. Many further structures of such tetra‐cationic silicon complexes may be accessible based on reactions of SiCl4 and SiBr4 with other phosphinic acid derivatives.

Furthermore, the activation of SiCl4 with chiral bisphosphoramides is known in literature32 and leads to cationic silicon species, which are employed as catalysts, for example, for the enantioselective allylation of aldehydes.32, 33, 34, 35 Also, phosphoric amides proved highly active as Lewis base catalysts for the disproportionation of methylchlorodisilanes.36 This activation of the weak Lewis acid SiCl4 and other chlorosilanes by that special kind of very polar Lewis base (which has an inherent negative connotation because of the toxicity of phosphoric amides) may be transferred to the chlorosilane/phosphinic acid derivatives system, which would represent a non‐toxic alternative to chlorosilane/phosphoramide systems. In addition to the donor qualities, dialkylphosphinic acids offer tools for including chiral information or linkers to solid supports (or both) by their alkyl backbone, rendering OP(OH)(alkyl)2 a fundamental motif worthwhile being studied in this regard.

CCDC 1967458 (SiPCl), 1967459 (SiPMe) and 1987161 (SiPMeBr) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

The financial support from the German Research Foundation (DFG; KR 1739/32‐1; BR 1540/5‐1) is gratefully acknowledged.

J. Kowalke, J. Wagler, C. Viehweger, E. Brendler, E. Kroke, Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 8003.

References

- 1. Rendler S., Oestreich M., Synthesis 2005, 11, 1727–1747. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tateiwa J.-i., Hosomi A., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 1445–1448. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holmes R. R., Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 927–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wagler J., Böhme U., Kroke E., Higher-Coordinates Molecular Silicon Compounds in Functional Molecular Silicon Compounds I. 155 (Ed.: D. Scheschkewitz), Springer, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London, 2014, pp. 29–105. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Finger L. W., Hazen R. M., Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 1991, 47, 561–580. [Google Scholar]

- 6.“The Crystal Chemistry of Phosphate Minerals”: Huminicki D. M. C., Hawthorne F. C. in Phosphates, Vol. 48 (Ed.: M. J. Kohn, J. Rakovan, J. M. Hughes), De Gruyter, Inc., Boston, 2019, pp. 123–254. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Poojary D. M., Borade R. B., F. L. Campbell III , Clearfield A., J. Solid State Chem. 1994, 112, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mayer H., Monatsh. Chem. 1974, 105, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jähnigen S., Brendler E., Böhme U., Kroke E., Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 7675–7677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Logemann C., Kluner T., Wickleder M. S., Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 758–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Logemann C., Witt J., Gunzelmann D., Senker J., Wickleder M. S., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2012, 638, 2053–2061. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Geeson M. B., Ríos P., Transue W. J., Cummins C. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6375–6384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seiler O., Burschka C., Fenske T., Troegel D., Tacke R., Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 5419–5424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kira M., Zhang L. C., Kabuto C., Sakurai H., Organometallics 1998, 17, 887–892. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kummer D., Seshadri T., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1977, 432, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deppisch B., Gladrow B., Kummer D., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1984, 519, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- 17. George K., Hector A. L., Levason W., Reid G., Sanderson G., Webster M., Zhang W., Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 1584–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Denmark S. E., Eklov B. M., Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 234–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dehnicke A.-F. S. K., Struct. Bonding 1976, 28, 51–82. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shihada A. F., Salih Z. S., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1980, 469, 159–163. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shihada A.-F., Weller F., Z. Naturforsch. B 1997, 52, 587–592. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weller F., Shihada A.-F., J. Organomet. Chem. 1987, 322, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shihada A.-F., Weller F., Z. Naturforsch. B 1998, 53, 699–703. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meisel M., Grunze H., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1973, 400, 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Corbridge D. E. C., Phosphorus: Chemistry, Biochemistry and Technology, 6th ed., Taylor&Francis, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moras D., Mitschler A., Weiss R., Chem. Commun. (London) 1968, 26a. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Crofts P. C., Kosolapoff G. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953, 75, 3379–3383. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grunze H., Z. Chem. 1966, 6, 266–267. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bekaert A., Lemoine P., Brion J. D., Viossat B., Z. Kristallogr. 2005, 220, 425–426. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kummer D., Köster H., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1973, 402, 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kummer D., Gaisser K. E., Seifert J., Wagner R., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1979, 459, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Denmark S. E., Pham S. M., Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 2201–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Denmark S. E., Beutner G. L., Wynn T., Eastgate M. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 3774–3789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Denmark S. E., Eklov B. M., Yao P. J., Eastgate M. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 11770–11787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Denmark S. E., Wynn T., Beutner G. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 13405–13407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Herzog U., Richter R., Brendler E., Roewer G., J. Organomet. Chem. 1996, 507, 221–228. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary