CASE

A previously healthy 35-year-old male presented to our hospital in mid-March 2020 with an acute subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). The patient had been in the shower when he experienced a sudden, pounding frontal headache associated with nausea and vomiting, blurred vision, and weakness. Initial imaging confirmed the presence of an SAH; follow-up computerized tomography angiography did not identify an aneurysm or other cause for the SAH. The patient’s mental status and oxygenation rapidly deteriorated. He required intubation to protect his airway and was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) on hospital day zero (HD0). Given the increasing incidence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at the time and a documented COVID-19 exposure at the patient’s place of work 2 days prior to admission, the clinical team was concerned that infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was a potential cause of his respiratory failure. It was not believed that the SAH was secondary to COVID-19, though infection prevention measures were initiated upon admission and a nasopharyngeal (NP) swab was submitted from the ICU for molecular testing. The analysis was performed in our hospital microbiology lab utilizing the Quidel Lyra SARS-CoV-2 molecular assay and reported a negative result.

He was extubated on HD1 and initially did well from the pulmonary standpoint while his SAH was under investigation. However, he developed diarrhea and mild elevations in his liver enzymes on HD7; chest imaging identified new bilateral airspace opacities, although the patient did not appear symptomatic from these. A second COVID-19 test was performed and was negative. On HD9, the patient became tachypneic and complained of worsening dyspnea. Chest X-ray confirmed bilateral pulmonary infiltrates concerning for COVID-19; thus, elective intubation was performed along with repeat molecular testing that was once again negative for SARS-CoV-2. He had a respiratory pathogen panel (RPP) (BioFire FilmArray Respiratory Panel 2.0) performed that was positive for rhinovirus/enterovirus and coronavirus 229E. Inflammatory markers were not assessed during the first week of hospitalization, but the patient exhibited marked elevations from HD8 onwards. C-reactive protein on HD8 and HD10 measured at 245.5 and 280.5 mg/liter (reference [Ref] ≤10 mg/liter), respectively, and d-dimers ranged from 794 and 3607 ng/ml between HD9 and HD16 (Ref ≤499 ng/ml FEU [fibrinogen equivalent units]).

The patient was monitored by the infectious disease team throughout his hospital stay and was continued on COVID-19 isolation precautions despite multiple negative tests. Specifically, he had a total of four negative NP swab results (all performed by the Quidel Lyra assay), submitted on HD1, HD7, HD9, and HD14. He underwent a bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) on HD15, and a portion of this specimen was sent to a reference laboratory for SARS-CoV-2 testing. A RPP was repeated on the BAL fluid specimen at the same time with negative results. He was extubated on HD17 after his respiratory status improved and discharged on HD20, the same day that his BAL fluid specimen returned positive for SARS-CoV-2. A specific cause for the SAH was never determined, though it was thought to be unrelated to the patient’s SARS-CoV-2 infection.

DISCUSSION

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel coronavirus, responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Infection with SARS-CoV-2 can result in a spectrum of symptoms ranging from mild shortness of breath and fever to respiratory failure and death. The virus is readily spread through respiratory droplets. Prompt and accurate diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection is essential for patient management and implementation of appropriate infection prevention.

The diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 has relied almost exclusively on molecular testing of upper and lower respiratory specimens. Of these specimen types, NP swabs have emerged as the most commonly utilized. One reason for this is that NP swabs strike a balance between perceived diagnostic performance, ease of collection, and patient safety. Although certain upper respiratory specimens may be easier to collect (for example, nasal swabs or oropharyngeal swabs), it has been well established for other respiratory viruses that sampling of the nasopharynx is needed for adequate sensitivity. Another reason why NP swabs are so commonly used is the availability of acceptable testing platforms. As of 7 April 2020 (when the BAL fluid sample for this patient was sent to a reference laboratory for testing), 28 of the 29 commercially available assays approved by the FDA for emergency use were for testing on nasopharyngeal swabs (Table 1). In contrast, only 22 assays were approved for oropharyngeal swabs, 15 for nasal specimens (aspirates/swabs), 7 for bronchoalveolar lavage specimens, 3 for sputum specimens, and 3 for tracheal aspirate specimens.

TABLE 1.

Summary of SARS-CoV-2 testing offered under FDA emergency use authorizationa

| Date of EUA (mo/day/yr) |

Company | Assay name | Limit of detection | Specimen type |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | OP | NA | BALF | SP | TA | ||||

| 4/3/2020 | Luminex Corporation | Aries SARS-CoV-2 assay | 7.5 × 104 GCE/ml | ✓ | |||||

| 3/30/2020 | Qiagen GmbH | QIAstat-Dx Respiratory SARS-CoV-2 | 500 copies/ml | ✓ | |||||

| 3/27/2020 | Abbott Diagnostics Scarborough, Inc. | ID Now COVID-19 | 125 GE/ml | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 3/23/2020 | BioFire Defense, LLC | BioFire COVID-19 test | 330 copies/ml | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 3/20/2020 | Cepheid | Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 test | 250 copies/ml | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 3/19/2020 | GenMark Diagnostics, Inc. | ePlex SARS-CoV-2 test | 1 × 105 copies/ml | ✓ | |||||

| 3/19/2020 | DiaSorin Molecular LLC | Simplexa COVID-19 Direct assay | 500 copies/ml (NP); 242 copies/ml (NS); 1,208 copies/ml (BALF) | ✓ | ✓ | Added 4/13 | |||

| 3/18/2020 | Abbott Molecular | Abbott RealTime SARS-CoV-2 assay | 100 copies/ml | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 3/17/2020 | Quidel Corporation | Lyra SARS-CoV-2 assay | 80 genomic RNA copies/μl | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 3/16/2020 | Hologic, Inc. | Panther Fusion SARS-CoV-2 assay | 1 × 10−2 TCID50 ml | ✓ | ✓ | Added 4/24 | |||

| 3/12/2020 | Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. (RMS) | cobas SARS-CoV-2 | 0.009 TCID50/ml (ORF1ab); 0.003 TCID50/ml (E gene) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 2/4/2020 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) | CDC 2019-nCoV Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel (CDC) | 1 × 100.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Added 4/13 | Added 4/13 | Added 4/13 |

The table includes a summary of assays from major manufacturers and does not include all assays with emergency use authorization (EUA). As of 7 April 2020, 29 commercially available assays were FDA approved for EUA. Abbreviations: NP, nasopharyngeal; OP, oropharyngeal; NA, nasal (nasal aspirate/swab); BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; SP, sputum; TA, tracheal aspirate; GCE, genomic copy equivalents; GE, genome equivalents; TCID50, 50% tissue culture infective doses; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-PCR.

The widespread use of NP swabs for molecular diagnosis may lead to the perception by many that they are the “gold standard” for diagnostic testing. Paired NP swabs have been used to evaluate the efficacy of other specimen types, and the need to establish equivalency to NP swab testing has even been made a requirement by the FDA for validation of select specimen types. However, this case highlights the peril of relying on NP swabs as the diagnostic gold standard for SARS-CoV-2.

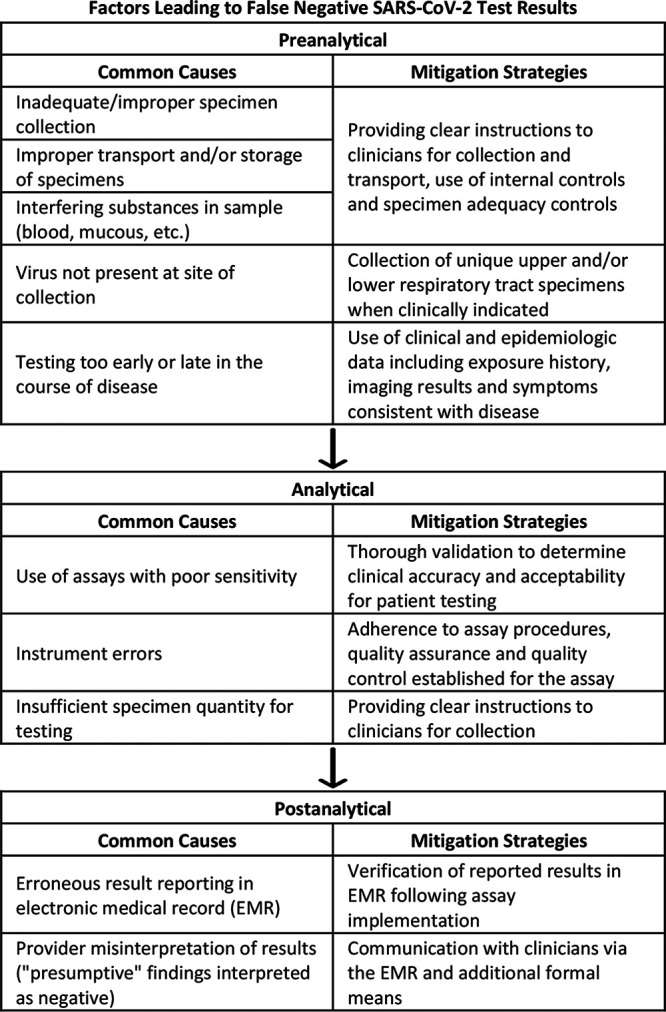

“False-negative” results are often the result of preanalytical, analytical, and postanalytical factors (Fig. 1). Perhaps one of the most commonly suspected causes of erroneous results is the diagnostic performance of the assay. Given the rapidly developing availability of different SARS-CoV-2 assays, there is an abundance of testing options with a relative paucity of performance data. Early comparisons of assays have demonstrated overall similar performances, though recent publications have highlighted newly recognized differences, such as a low clinical sensitivity of the Abbott ID Now assay in comparison to others (1). As more comparative data become available, it is likely that additional differences in assay performance will surface, emphasizing the need for proper laboratory evaluation. Though the assay utilized in this case (the Quidel Lyra SARS-CoV-2 assay) has not yet been formally evaluated in the published literature, our in-house validation supports similar clinical performance to other commercially available assays (including the Roche 6800 and Cepheid SARS-CoV-2 assays).

FIG 1.

False-negative SARS-CoV-2 test results can be caused by preanalytical, analytical, and postanalytical factors. Mitigation strategies can be used to either prevent false-negative results from occurring or prevent adverse patient events secondary to false-negative results.

Another important consideration is proper specimen collection. Nasopharyngeal swabs require insertion of the tip of the swab equal to the distance from the nostril to the outer opening of the ears. Although this may result in patient discomfort, sampling less aggressively can lead to inadequate sampling of the nasopharynx and false-negative results. Although some assays (for example, the CDC SARS-CoV-2 assay) contain PCR targets to ensure adequate sampling, these controls cannot determine whether the sampling was in the proper anatomic location. Some hospitals (including our own) have adopted the strategy of having dedicated teams of providers to obtain NP specimens in order to standardize and optimize collection.

The timing of specimen collection is another variable influencing positivity. Multiple studies demonstrate that the amount of virus present in the upper respiratory tract varies over the course of infection (2, 3), suggesting that viral loads are highest immediately following symptom onset and that virus can often be detected in upper respiratory specimens for greater than 2 weeks postsymptom onset (3). However, cases like ours suggest that even with multiple collections performed throughout the disease course, false-negative results can still occur. These types of occurrences may be difficult to account for in prospective studies, since the majority of these patients will be diagnosed as SARS-CoV-2 negative, and may therefore not receive follow-up testing.

Differences in specimen type performance may also contribute to discordant results. Recent data suggest that NP and sputum viral loads are closely related (4). However, several studies have demonstrated more-reliable results from nasal swabs compared to throat swabs early in the disease course (2, 3). Case reports of SARS-CoV-2 detection in sputum, tracheal aspirate, and BAL fluid specimens suggest that these specimens may be positive when NP swabs are negative, though large-scale studies have yet to be published (5). Even if such studies were to be performed, they may be biased, as only the most critically ill patients would be tested using lower respiratory specimens. Overall availability of lower respiratory testing is also a challenge to obtaining these data. At the time when our patient was tested, only 8 of 29 FDA emergency use authorized (EUA) assays allowed testing of BAL fluid specimens. Our available in-house tests were not authorized for BAL fluid samples, though sending out testing from alternative sample types was not an initial consideration for our clinicians, who were concerned about increased turnaround time and had the perception that NP swabs could give equivalent results to a more invasive test.

It has become clear that negative NP swabs alone do not rule out SARS-CoV-2 infection, and as of now, there is no single “ideal” specimen for the diagnosis of COVID-19 (5). Consequently, regulatory agencies may have to reevaluate standards used to assess new assays and specimen types, and clinicians may need to reconsider how they establish or exclude a diagnosis of COVID-19. Professional agencies have already recognized the need for additional diagnostic strategies involving more than just a single test. Updated IDSA (Infectious Diseases Society of America) guidelines for COVID-19 diagnosis describe an algorithmic approach based on patient symptomatology, suspicion for infection, hospitalization status, and availability of lower respiratory specimens (6). As tools like serologic testing become more readily available, the “case definition” of SARS-CoV-2 infection is likely to mature, which should allow for better evaluation and refinement of diagnostic strategies.

This case illustrates how reliance on a single test from a single specimen type to rule out SARS-CoV-2 infection can be problematic. Of note, the health care providers caring for this patient had a strong suspicion for COVID-19 throughout the hospitalization, and as such maintained appropriate infection prevention protocols. This case emphasizes the importance of considering clinical presentation and the necessity for its inclusion in any diagnostic algorithm for COVID-19. Even in the setting of a public health crisis with a novel pathogen, the old adage still rings true: treat the patient, not the result.

SELF-ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS

- Which of the following best describes potential reasons for false-negative molecular testing for SARS-CoV-2?

- Analytical errors involving improper transport and storage of specimens

- Preanalytical errors stemming from the limited sensitivity of the molecular test

- Analytical errors due to incorrect sampling by the clinician obtaining the specimen for testing

- Preanalytical errors related to interfering substances inhibiting molecular testing

- A patient in acute respiratory distress is admitted to the ICU, with strong clinical suspicion of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Initial molecular testing on admission is negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. What should additional clinical management of this patient include?

- Assume the patient is negative to avoid overuse of personal protective equipment

- Test lower respiratory tract samples if available to help confirm the diagnosis of COVID-19

- Perform chest X-ray to confirm negative result and definitively rule out COVID-19

- Perform antibody testing to confirm negative result and definitively rule out COVID-19

- Which of the following described processes would result in the best sampling of the nasopharynx for COVID-19 testing?

- A single flocked swab inserted into the nares to a depth equal to the distance from the nares to the opening of the ears

- A single flocked swab inserted into the oral cavity to the back of the throat past the palatine tonsils

- A single flocked swab inserted 3 cm deep into the right nares and then reinserted 3 cm deep into the left nares

- A single flocked swab inserted into the nares to a depth equal to the distance from the nares to the eyes

For answers to the self-assessment questions and take-home points, see https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01196-20 in this issue.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Barnes Jewish hospital clinical and laboratory health care teams for their exceptional patient care.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harrington A, Cox B, Snowdon J, Bakst J, Ley E, Grajales P, Maggiore J, Kahn S. 23 April 2020. Comparison of Abbott ID Now and Abbott m2000 methods for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 from nasopharyngeal and nasal swabs from symptomatic patients. J Clin Microbiol doi: 10.1128/JCM.00798-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z, Yu J, Kang M, Song Y, Xia J, Guo Q, Song T, He J, Yen HL, Peiris M, Wu J. 2020. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med 382:1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiao AT, Tong YX, Gao C, Zhu L, Zhang YJ, Zhang S. 2020. Dynamic profile of RT-PCR findings from 301 COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. J Clin Virol 127:104346. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan Y, Zhang D, Yang P, Poon LLM, Wang Q. 2020. Viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. Lancet Infect Dis 20:411–412. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30113-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winichakoon P, Chaiwarith R, Liwsrisakun C, Salee P, Goonna A, Limsukon A, Kaewpoowat Q. 2020. Negative nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs do not rule out COVID-19. J Clin Microbiol 58:e00297-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00297-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhimraj A, Morgan RL, Shumaker AH, Lavergne V, Baden L, Cheng VC, Edwards KM, Gandhi R, Muller WJ, O’Horo JC, Shoham S, Murad MH, Mustafa RA, Sultan S, Falck-Ytter Y. 27 April 2020. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]