Summary

Severe acute respiratory syndrome‐corona virus‐2, which causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), is highly contagious. Airway management of patients with COVID‐19 is high risk to staff and patients. We aimed to develop principles for airway management of patients with COVID‐19 to encourage safe, accurate and swift performance. This consensus statement has been brought together at short notice to advise on airway management for patients with COVID‐19, drawing on published literature and immediately available information from clinicians and experts. Recommendations on the prevention of contamination of healthcare workers, the choice of staff involved in airway management, the training required and the selection of equipment are discussed. The fundamental principles of airway management in these settings are described for: emergency tracheal intubation; predicted or unexpected difficult tracheal intubation; cardiac arrest; anaesthetic care; and tracheal extubation. We provide figures to support clinicians in safe airway management of patients with COVID‐19. The advice in this document is designed to be adapted in line with local workplace policies.

Keywords: airway, anaesthesia, coronavirus, COVID‐19, critical care, difficult airway, intubation

Introduction

This consensus statement has been brought together at short notice to advise on airway management for patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). It applies to all those who manage the airway (‘airway managers’). It draws on several sources including relevant literature but more immediately from information from clinicians practicing in China, Italy and airway experts in the UK. It is probably incomplete but aims to provide an overview of principles. It does not aim to propose or promote individual devices. The advice in this document is designed to be adapted in line with local workplace policies. This document does not discuss when to intubate patients, the ethics of complex decision‐making around escalation of care or indemnity for staff necessarily working outside their normal areas of expertise. It does not discuss treatment of COVID‐19 nor intensive care ventilatory strategies but rather it focuses on airway management in patients with COVID‐19.

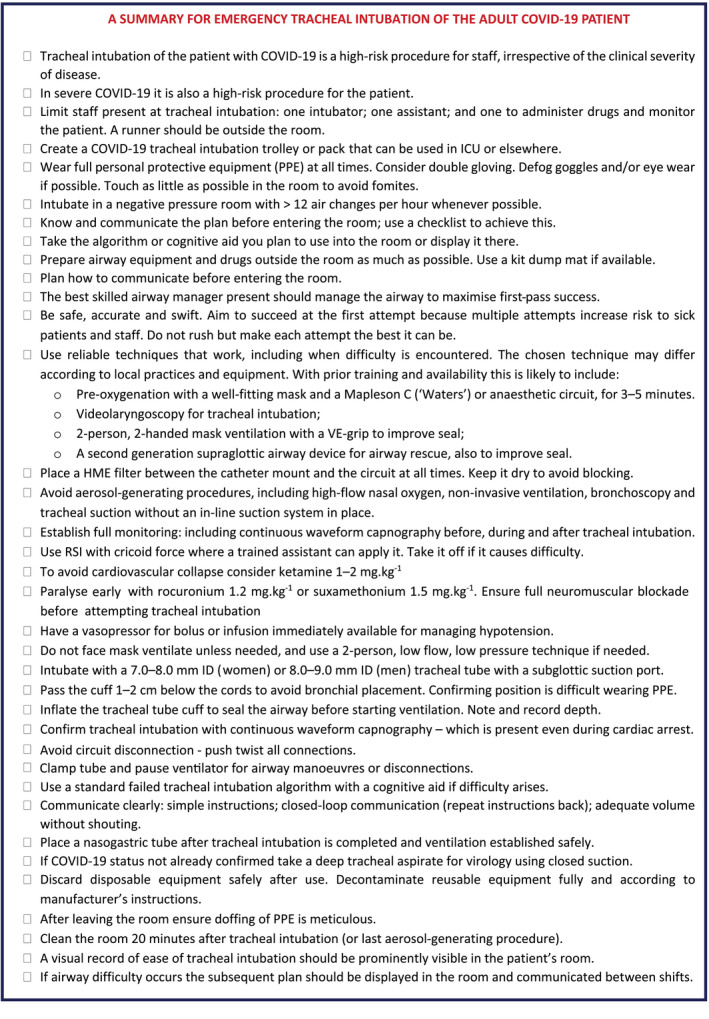

The one‐page summary (Fig. 1) may be useful as a stand‐alone resource, and the principles of safe, accurate and swift management must always be considered (Fig. 2). The full paper is likely to be of greater value as a reference when planning local services. The advice is based on available evidence and consensus at the time of writing, in what is a fast‐moving arena. Some references refer to English or UK governmental sites for up‐to‐date advice. Those practicing in other countries should be aware that advice in their country may differ and is regularly updated, so they should also refer to their own national guidance.

Figure 1.

One‐page summary for emergency tracheal intubation of the coronavirus disease 2019 patient.

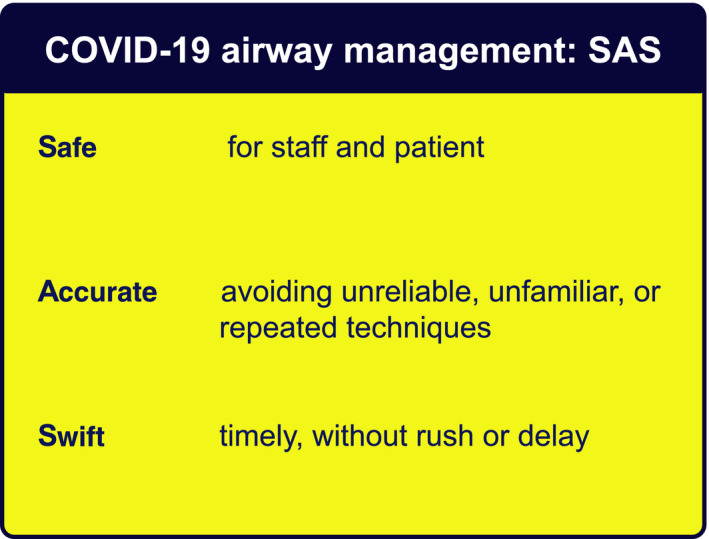

Figure 2.

Principles of coronavirus disease 2019 airway management.

COVID‐19: the need for airway interventions and risks to airway managers

Severe acute respiratory syndrome‐corona virus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), which causes COVID‐19, is a single‐stranded ribonucleic acid ‐encapsulated corona virus and is highly contagious. Transmission is thought to be predominantly by droplet spread (i.e. relatively large particles that settle from the air), and direct contact with the patient or contaminated surfaces (fomites), rather than airborne spread, in which smaller particles remain in the air longer 1, 2. Procedures during initial airway management and in the intensive care unit (ICU) may generate aerosols which will increase risk of transmission 1. Healthcare workers (HCW) treating patients with COVID‐19 are at increased risk of contracting the illness 3, 4, 5, 6.

The predominant COVID‐19 illness is a viral pneumonia. Airway interventions are mainly required for tracheal intubation and establishing controlled ventilation. However, as the epidemic increases, there will be many patients in the community with COVID‐19 who are asymptomatic or have mild disease. These patients may present for emergency surgery for unrelated conditions.

Staff safety

The highest viral load of SARS‐CoV‐2 appears in the sputum and upper airway secretions 1. Tracheal intubation is a potentially high‐risk procedure for the airway manager, particularly as it risks exposure to a high viral load and if transmission occurs to HCWs, this may be associated with more severe illness 4. For this reason, airway managers should take appropriate precautions.

This is clearly an area of great importance 7. Whereas this article focuses predominantly on management of the airway, staff protection is too important not to include. We discuss in brief: aerosol‐generating procedures and personal protective equipment are only one part of a system to reduce viral exposure. There is extensive advice which is updated regularly on infection prevention and control related to COVID‐19 8.

Aerosol‐generating procedures

Severe acute respiratory syndrome‐corona virus‐2 is spread by inhalation of infected matter containing live virus (which can travel up to 2 m) or by exposure from contaminated surfaces. Aerosol‐generating procedures create an increased risk of transmission of infection.

A systematic review of infection risk to HCWs 9, based on limited literature, ranked airway procedures in descending order of risk as: (1), tracheal intubation; (2), tracheostomy (and presumed for emergency front‐of‐neck airway (FONA)); (3), non‐invasive ventilation (NIV); and (4), mask ventilation. Other potentially aerosol‐generating procedures include: disconnection of ventilatory circuits during use; tracheal extubation; cardiopulmonary resuscitation (before tracheal intubation); bronchoscopy; and tracheal suction without a ‘closed in‐line system.’ Transmission of infection is also likely to be possible from faeces and blood although detection of virus in the blood is relatively infrequent 1.

High‐flow and low‐flow nasal oxygen

There is much debate about the degree to which high‐flow nasal oxygen is aerosol‐generating and the associated risk of pathogen transmission 10. Older machines may expose staff to greater risk. The risk of bacterial transmission has been assessed as low 11, but the risk of viral spread has not been studied. There are other reasons not to use high‐flow nasal oxygen in a situation of mass illness and mass mechanical ventilation. First, it may simply delay tracheal intubation in those for whom treatment escalation is appropriate 12. Second, the very high oxygen usage risks depleting oxygen stores, which is a risk as a hospital's oxygen usage may increase many‐fold during an epidemic. For all these reasons, high‐flow nasal oxygen is not currently recommended for these patients around the time of tracheal intubation.

Low‐flow nasal oxygen (i.e. < 5 l.min−1 via normal nasal cannula) may provide some oxygenation during apnoea and might therefore delay or reduce the extent of hypoxaemia during tracheal intubation. There is no evidence we are aware of regarding its ability to generate viral aerosols, but on balance of likelihood, considering the evidence with high‐flow nasal oxygen, this appears unlikely. It is neither recommended nor recommended against during emergency tracheal intubation of patients who are likely to have a short safe apnoea time. In patients who are not hypoxaemic, without risk factors for a short safe apnoea time, and who are predicted to be easy to intubate, it is not recommended.

Systems to prevent contamination of healthcare workers, including personal protective equipment

Personal protective equipment (PPE) forms only one part of a system to prevent contamination and infection of HCWs during patient care. In addition to PPE, procedures such as decontamination of surfaces and equipment, minimising unnecessary patient and surface contact and careful waste management are essential for risk reduction. The virus can remain viable in the air for a prolonged period and on non‐absorbent surfaces for many hours or even days 2. The importance of cleaning, equipment decontamination and correct use of PPE use cannot be overstated. In the SARS epidemic, which was also caused by a corona virus, HCW were at very high risk for infection, but reliable use of PPE significantly reduced this risk 13, 14.

Personal protective equipment is not discussed here in detail. General principles are that it should be simple to remove after use without contaminating the user and complex systems should be avoided. It should cover the whole upper body. It should be disposable whenever possible. It should be disposed of appropriately, immediately after removal (‘doffing’). A ‘buddy system’ (observer), including checklists, is recommended to ensure donning and doffing is performed correctly. Personal protective equipment should be used when managing all COVID‐19 patients. Airborne precaution PPE is the minimal appropriate for all airway management of patients with known COVID‐19 or those being managed as if they are infected. The Intensive Care Society has made a statement on PPE, describing minimal requirements and noting that PPE needs to be safe, sufficient and used in a manner that ensures supplies are sustainable 15.

It has been suggested that double‐gloving for tracheal intubation might provide extra protection and minimise spread by fomite contamination of equipment and surrounds 16. Fogging of googles and/or eyewear when using PPE is a practical problem for tracheal intubation in up to 80% of cases (personal communication Huafeng Wei, USA); anti‐fog measures and iodophor or liquid soap may improve this. Training and practising PPE use before patient management is essential for staff and patient safety.

Ideally, patients are managed in single, negative pressure rooms with good rates of air exchange (> 12 exchanges per hour) to minimise risk of airborne exposure 17. In reality, many ICU side rooms do not meet this standard and, when critical care is expanded to areas outside of ICU, airway management may take place in rooms with positive pressure (e.g. operating theatres) or those with reduced air exchanges. Most operating theatres are positive pressure with high rates of air exchange. These factors may have implications for transmission risk, retention of aerosols and therefore what constitutes appropriate PPE 18. Guidance on PPE requirements after tracheal intubation is beyond the scope of this document 8.

Tracheal intubation of the critically ill

This is a high‐risk procedure with physiological difficulty: around 10% of patients in this setting develop severe hypoxaemia (SpO2 < 80%) and approximately 2% experience cardiac arrest 19, 20. These figures are likely to be higher for patients with severe COVID‐19 and drive some of the principles below. The first‐pass success rate of tracheal intubation in the critically ill is often < 80% with up to 20% of tracheal intubations taking > two attempts 19. The increased risk of HCW infection during multiple airway manipulations necessitates the use of airway techniques which are reliable and maximise first‐time success. This applies equally to rescue techniques if tracheal intubation fails at first attempt.

Delivering care in non‐standard environments and by or with staff less trained in critical care

It is likely that management in expanded critical care services will involve working in areas other than standard critical care units. This creates logistical difficulty in airway management.

Monitoring should adhere to Association of Anaesthetists standards and in particular, continuous waveform capnography should be used for every tracheal intubation and in all patients dependent on mechanical ventilation unless this is impossible. Note that even in cardiac arrest during lung ventilation there will be a capnograph trace – a flat trace indicates and should be managed as oesophageal intubation until proven otherwise (‘no trace = wrong place’) 21, 22.

Caring for COVID‐19 patients may also involve recruitment of staff to the critical care team who do not normally work in that setting and have received emergency training to enable them to deliver care alongside fully trained staff. In severe escalation, even these standards might become difficult to maintain. The Chief Medical Officer has written to all UK doctors to explain regulatory support for this 23. At its extreme peak, care may also be delivered by retired staff and medical students. Due to the high consequence nature of airway management in these patients, both for the patient and staff, it is recommended that these staff do not routinely take part in airway management of COVID‐19 patients.

In some circumstances, the development of a specific tracheal intubation team may be an appropriate solution where case load is sufficient.

The most appropriate airway manager

We recommend that the ‘most appropriate’ clinician manages the airway. This is to enable successful airway management that is safe, accurate and swift. Deciding who is the most appropriate airway manager requires consideration of factors such as the available clinicians’ airway experience and expertise, whether they fall into any of the groups of clinicians who would be wise to avoid tracheal intubation, the predicted difficulty of airway management, its urgency and whether a tracheal intubation team is available. On occasion, this may necessitate senior anaesthetists managing airways in lieu of junior anaesthetists or intensivists who do not have an anaesthesia background. However, it is unlikely and unnecessary that tracheal intubation will be the exclusive preserve of one specialty. Judgement will be required.

Staff who should avoid involvement in airway management

This is a problematic area and there is no national guidance. In some locations, healthcare providers are excluding staff who are themselves considered high risk. Current evidence would include in this group: older staff (the mortality curve rises significantly > 60 years of age); cardiac disease; chronic respiratory disease; diabetes; recent cancer; and perhaps hypertension 4, 6. Whereas no clear evidence exists, it is logical to also not include staff who are immunosuppressed or pregnant from airway management of COVID‐19 patients.

Simulation

Due to the uncertainties inherent in the new processes to be adopted, we recommend regular and full in‐situ simulation of planned processes, to facilitate familiarity and identification of otherwise unidentified problems, before these processes are used in urgent and emergent patient care situations.

Single vs. reusable equipment

Where practical, single‐use equipment should be used 24. However, where single‐use equipment is not of the same quality as re‐usable equipment this creates a conflict. It is also possible that supplies of single‐use equipment may run short. The balance of risk to patients and staff (frontline and those involved in transport and decontamination of equipment) should be considered if a decision is made to use reusable airway equipment. We recommend use of the equipment most likely to be successful, while balancing the above factors. Reusable equipment will need appropriate decontamination. It is important to precisely follow manufacturer's instructions for decontamination of reusable equipment.

When to intubate the critically ill COVID‐19 patient

This document does not consider when patients’ tracheas should be intubated. However, in order to avoid aerosol‐generating procedures, it is likely that patients’ tracheas may be intubated earlier in the course of their illness than in other settings.

Fundamentals of airway management for a patient with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19

Airway management for patients who are suspected or confirmed to have COVID‐19 follows similar principles in both emergency and non‐emergency settings (Fig. 1).

-

Prepare.

-

a

Institutional preparation (equipment for routine management and for managing difficulty; adequate numbers of appropriately trained staff; availability of tracheal intubation checklists; PPE etc.) should be in place well before airway management occurs. If this does not already exist, it is strongly recommended it is put in place urgently. Resources from this guideline may form part of that preparation.

-

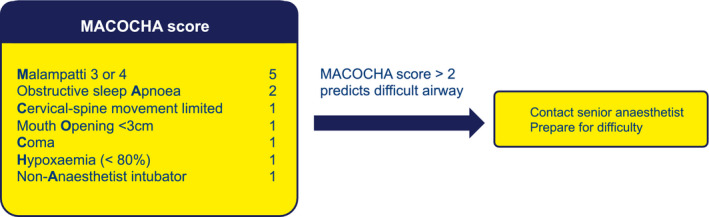

bTeam and individual preparation require knowledge of the institutional preparation, the skills required, how to use PPE correctly and assessment of the patient's airway to predict difficulty and prepare the airway strategy (Fig. 3). It is accepted that MACOCHA (Malampatti, obstructive sleep apnoea, c‐spine movement, mouth opening, coma, hypoxaemia, non‐anaesthetist intubator 25) is not widely used but it is validated and recommended.

Figure 3.

MACOCHA score and prediction of difficult intubation. Adapted from 23.

MACOCHA score and prediction of difficult intubation. Adapted from 23.

-

a

Create a COVID‐19 tracheal intubation trolley or pack. Critically ill patients may need to be intubated in a location other than ICU. On ICU, tracheal intubation will likely take place in single rooms. Prepare a tracheal intubation trolley or pack that can be taken to the patient and decontaminated after use. The Supporting Information (Appendix S1) in the online supplementary material illustrates and provides some guidance on its contents.

Have a strategy. The airway strategy (the primary plan and the rescue plans, and when they are transitioned to) should be in place and the airway team briefed before any part of airway management takes place.

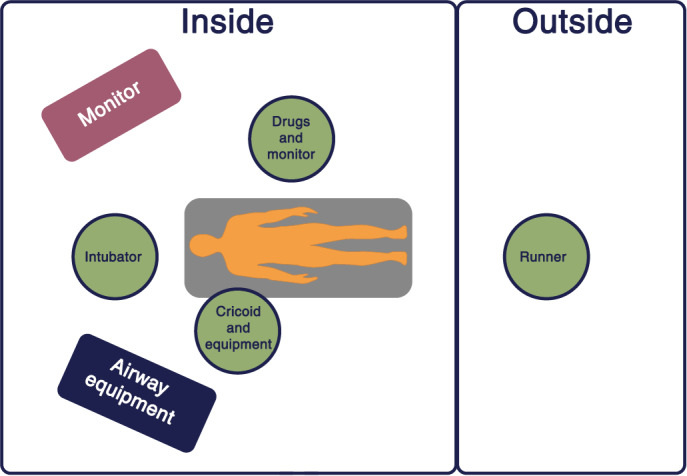

- Involve the smallest number of staff necessary. This is not an argument for solo operators but staff who have no direct role in the airway procedure should not unnecessarily be in the room where airway management is taking pace. Three individuals are likely required: an intubator; an assistant; and a third person to give drugs and watch monitors. A runner should be watching from outside and be able to summon help rapidly if needed (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Personnel plan for tracheal intubation of a patient with coronavirus disease 2019. Adapted from 20.

Personnel plan for tracheal intubation of a patient with coronavirus disease 2019. Adapted from 20. Wear appropriate, checked PPE (see above) . Even in an emergency and including cardiac arrest, PPE should be in worn and checked before all airway management and staff should not expose themselves to risk in any circumstance.

Avoid aerosol‐generating procedures wherever possible. If a suitable alternative is available, use it. If aerosol generation takes place, the room is considered contaminated, airborne precaution PPE should be used and the room should be deep cleaned after 20 min 24.

Focus on promptness and reliability. The aim is to achieve airway management successfully at the first attempt. Do not rush but make each attempt the best it can be. Multiple attempts are likely to increase risk to multiple staff and to patients.

-

Use techniques that are known to work reliably across a range of patients, including when difficulty is encountered. The actual technique may differ according to local practices and equipment. Where training and availability is in place this is likely to include:

-

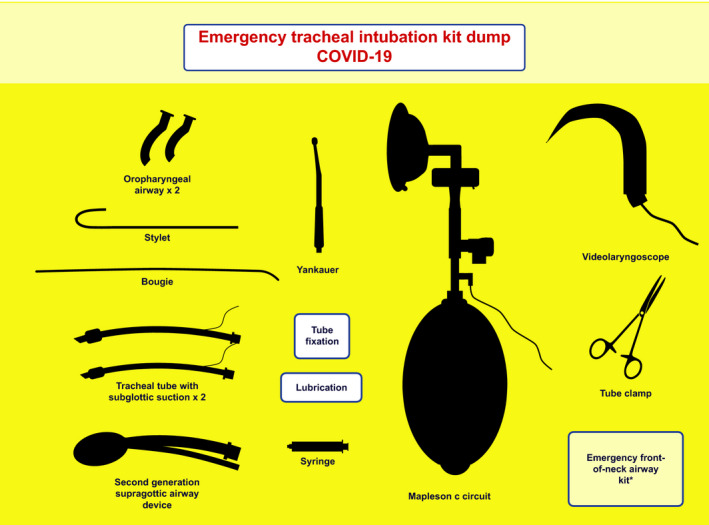

aUse of a kit dump mat (Fig. 5);

Figure 5.

Exemplar of kit dump mat. The emergency front‐of‐neck airway kit may be excluded from the airway kit dump due to the risk of contamination and could be placed outside of the room with immediate access if required.

Exemplar of kit dump mat. The emergency front‐of‐neck airway kit may be excluded from the airway kit dump due to the risk of contamination and could be placed outside of the room with immediate access if required. -

b

Videolaryngoscopy for tracheal intubation;

-

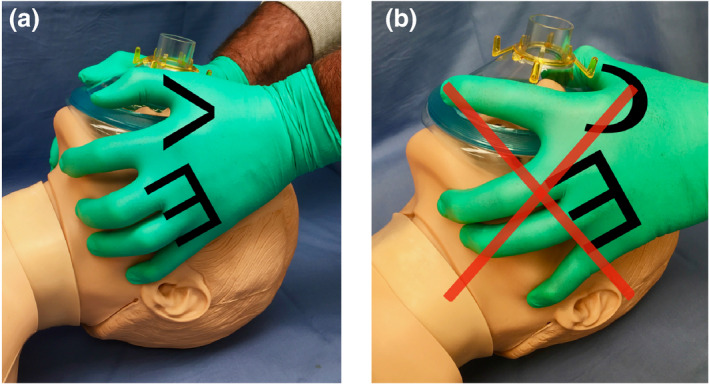

cA 2‐person 2‐handed mask ventilation with a VE‐grip (Fig. 6);

Figure 6.

(a). Two‐handed two‐person bag‐mask technique with the VE hand position; the second person squeezes the bag. (b). The C hand position, which should be avoided. Reproduced with permission of Dr A. Matioc.

(a). Two‐handed two‐person bag‐mask technique with the VE hand position; the second person squeezes the bag. (b). The C hand position, which should be avoided. Reproduced with permission of Dr A. Matioc. -

d

A second‐generation supraglottic airway device (SGA) for airway rescue (e.g. i‐gel, Ambu Aura Gain, LMA ProSeal, LMA Protector)

-

a

The most appropriate airway manager should manage the airway. See above.

Do not use techniques you have not used before or are not trained in. Again, for the reasons stated above, this is not a time to test new techniques.

-

Ensure all necessary airway kit is present in the room before tracheal intubation takes place. This includes the airway trolley and a cognitive aid consistent with the rescue strategy.

-

a

Monitoring including working continuous waveform capnography

-

b

Working suction

-

c

Ventilator set up

-

d

Working, checked intravenous (i.v.) access

-

a

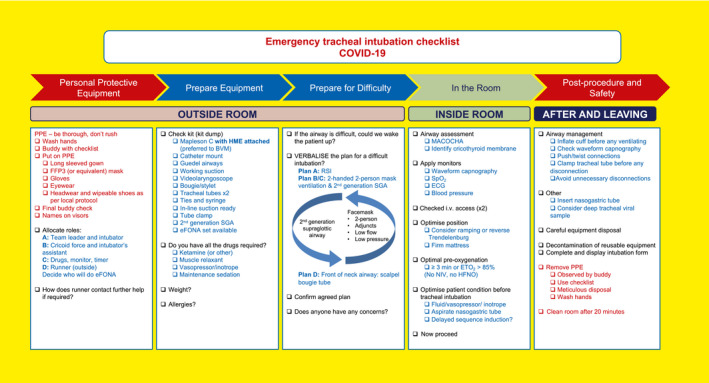

- Use a tracheal intubation checklist (Fig. 7 and also see Supporting Information, Appendix S2). This is designed to aid preparedness and should be checked before entering the patient's room as part of preparation.

Figure 7.

Emergency tracheal intubation checklist in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019. Adapted from 20 with permission.

Emergency tracheal intubation checklist in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019. Adapted from 20 with permission. - Use a cognitive aid if difficulty arises (Fig. 8). Airway difficulty leads to cognitive overload and failure to perform optimally. A cognitive aid will help focus the team and enhance transitioning through the algorithm. Two algorithms are provided: that derived from the Difficult Airway Society (DAS) 2018 guidelines for tracheal intubation of the critically ill 20 has intentionally been reduced in scope and choices removed to accommodate the current setting and encourage reliable and prompt decision‐making and actions.

Figure 8.

Use clear language and closed loop communication. It may be hard to communicate when wearing PPE and staff may be working outside normal areas of practice. Give simple instructions. Speak clearly and loudly, without shouting. When receiving instructions repeat what you have understood to the person speaking. If team members do not know each other well, a sticker with the individual's name can be placed on the top of the visor to aid communication with other staff.

Anaesthetic and airway technique for emergency tracheal intubation

-

1

A rapid sequence induction (RSI) approach is likely to be adopted. Use of cricoid force is controversial 28, so use it where a trained assistant can apply it but promptly remove it if it contributes to tracheal intubation difficulty.

-

2

Meticulous pre‐oxygenation should be with a well‐fitting mask for 3–5 min. A closed circuit is optimal (e.g. anaesthetic circle breathing circuit) and a rebreathing circuit (e.g. Mapleson's C (‘Waters’) circuit is preferable to a bag‐mask which expels virus‐containing exhaled gas into the room.

-

3

Place a heat and moisture exchange (HME) filter between the catheter mount and the circuit. Non‐invasive ventilation should be avoided. High‐flow nasal oxygen is not recommended.

-

4

Patient positioning, including ramping in the obese and reverse Trendelenburg positioning, should be adopted to maximise safe apnoea time.

-

5

In agitated patients, a delayed sequence tracheal intubation technique may be appropriate.

-

6

If there is increased risk of cardiovascular instability, ketamine 1–2 mg.kg−1 is recommended for induction of anaesthesia. Rocuronium 1.2 mg.kg−1 for neuromuscular blockade, should be given as early as practical. These measures minimise apnoea time and risk of patient coughing. If suxamethonium is used the dose should be 1.5 mg.kg−1.

-

7

Ensure full neuromuscular blockade before tracheal intubation is attempted. A peripheral nerve stimulator maybe used or wait 1 minute.

-

8

Ensure a vasopressor for bolus or infusion is immediately available for managing hypotension.

-

9

Only after reliable loss of consciousness – to avoid coughing – gentle continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) may be applied, if the seal is good, to minimise the need for mask ventilation. Bag‐mask ventilation may be used to assist ventilation and prevent hypoxia if indicated. Use a Guedel airway to maintain airway patency. Use the 2‐handed, 2‐person technique with a VE‐grip to improve seal particularly in the obese patient 29. When bag‐mask ventilation is applied, minimal oxygen flows and airway pressures consistent with achieving this goal should be used.

-

10

Alternatively, a second‐generation SGA may be inserted, after loss of consciousness and before tracheal intubation, to replace the role of bag‐mask ventilation or if this is difficult 7, 30.

-

11

Laryngoscopy should be undertaken with the device most likely to achieve prompt first‐pass tracheal intubation in all circumstances in that operator's hands – in most fully trained airway mangers this is likely to be a videolaryngoscope.

-

a

Stay as distant from the airway as is practical to enable optimal technique, whatever device is used

-

b

Using a videolaryngoscope with a separate screen enables the operator to stay further from the airway and this technique is recommended for those trained in their use.

-

c

If using a videolaryngoscope with a Macintosh blade, a bougie may be used.

-

d

If using a videolaryngoscope with a hyperangulated blade, a stylet is required.

-

e

Where a videolaryngoscope is not used, a standard MacIntosh blade and a bougie (either pre‐loaded within the tracheal tube or immediately available) is likely the best option

-

f

If using a bougie or stylet, be careful when removing it so as not to spray secretions on the intubating team

-

a

-

12

Intubate with a tracheal tube size 7.0–8.0 mm internal diameter (ID) in women or 8.0–9.0 mm ID in mens, in line with local practice. Use a tracheal tube with a subglottic suction port where possible.

-

13

At tracheal intubation, place the tracheal tube without losing sight of it on the screen and pass the cuff 1–2 cm below the cords, to avoid bronchial intubation.

-

14

Inflate the cuff with air to a measured cuff pressure of 20–30 cmH2O immediately after tracheal intubation.

-

15

Secure the tracheal tube as normal.

-

16

Start mechanical ventilation only after cuff inflation. Ensure there is no leak.

-

17

Confirm tracheal intubation with continuous waveform capnography.

-

18

Confirming correct depth of insertion may be difficult.

-

a

Auscultation of the chest is difficult when wearing airborne precaution PPE and is likely to risk contamination of the stethoscope and staff, so is not recommended.

-

b

Watching for equal bilateral chest wall expansion with ventilation is recommended.

-

c

Lung ultrasound or chest x‐ray may be needed if there is doubt about bilateral lung ventilation.

-

a

-

19

Once correct position is established record depth of tracheal tube insertion prominently.

-

20

Pass a nasogastric tube after tracheal intubation is complete and ventilation established to minimise the need for later interventions.

-

21

If the patient has not yet been confirmed as COVID‐19 positive collect a deep tracheal sample using closed suction for COVID‐19 testing. Some upper airway samples are false negatives.

-

22

A visual record of tracheal intubation should be prominently visible on the patient's room (see also Supporting Information, Appendix S3).

Unexpected difficulty

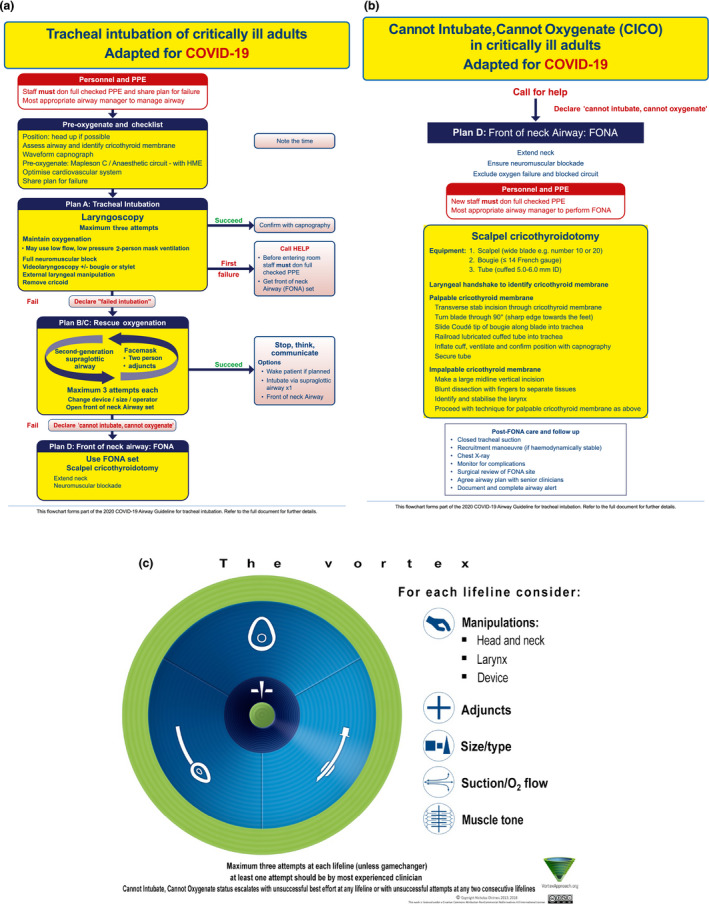

-

The basic algorithm for tracheal intubation can usefully adhere to the simplified DAS 2018 guideline for tracheal intubation of the critically ill patient (Figs. 8a and 8b) or the Vortex approach (Fig. 8c). If there is difficulty with tracheal intubation this should be managed according to standard rescue algorithms with attention to the following:

-

a

Transition through the algorithm promptly, consider minimising number of attempts at each technique.

-

b

Declare difficulty or failure to the team at each stage.

-

c

Mask ventilation may be deferred initially and a second‐generation SGA used as an alternative between attempts at laryngoscopy. This may reduce aerosol generation due to improved airway seal

-

d

If an emergency FONA is required, the simplified DAS 2018 guidance should be followed (Fig. 8b). The scalpel‐bougie‐tube technique is particularly preferred in COVID‐19 patients due to the risk of aerosolisation with the oxygen insufflation associated with cannula techniques. To improve simplicity, we have only provided the option of the scalpel‐bougie‐tube technique. If a different technique is specifically adopted and trained for in your department, this may also be appropriate.

-

a

Where there is problem, a difficult airway plan should be recorded, prominently displayed and communicated to staff at shift change overs (an example of an ICU airway alert form is shown in Supplementary Appendix S4).

Predicted difficult airway

The choice of airway technique in a predicted difficult airway will be specific to the patient's needs and is therefore beyond the scope of this guideline.

-

Many techniques for managing the difficult airway will include potentially aerosol‐generating procedures – see above. While there are reports from other countries of use of awake tracheal intubation note:

-

a

Topicalisation of the airway will need to be considered carefully to minimise aerosol‐generating procedures and coughing.

-

b

Flexible bronchoscopy techniques (whether alone, via a SGA conduit or with a videolaryngoscope, so called video‐assisted flexible intubation) are likely to be aerosol‐generating and therefore unlikely to be first choice.

-

c

Alternative difficult tracheal intubation techniques include tracheal intubation via an SGA including the intubating laryngeal mask airway (blind or flexible bronchoscope‐assisted), or with (video guidance and an Aintree intubation catheter).

-

a

Airway management after tracheal intubation and trouble shooting

Use an HME filter close to the patient, instead of a heated humidified circuit (wet circuit) but take care this does not become wet and blocked.

Monitor airway cuff pressure carefully to avoid airway leak. If using high airway pressures, ensure the tracheal tube cuff pressure is at least 5 cmH2O above peak inspiratory pressure. Cuff pressure may need to be increased before any recruitment manoeuvres to ensure there is no cuff leak.

Monitor and record tracheal tube depth at every shift to minimise risk of displacement.

Managing risk of tracheal tube displacement. This is a risk during patient repositioning including: prone positioning; turning patients; nasogastric tube aspiration or positioning; tracheal suction; and oral toilet. Cuff pressure and tracheal tube depth should be checked and corrected both before and after these procedures. There is a risk of tracheal tube displacement during sedation holds and this should be considered when planning these (e.g. timing, nursing presence etc.).

Suction. Closed tracheal suction is mandatory wherever available.

Tracheal tube cuff leak. If a cuff leak develops to avoid aerosol‐generation pack the pharynx while administering 100% oxygen and setting up for re‐intubation. Immediately before re‐intubation, pause the ventilator.

-

Airway interventions. Physiotherapy and bagging, transfers, prone positioning, turning the patient, tube repositioning. If the intervention requires a disconnection of the ventilator from the tracheal tube before the airway intervention:

-

a

Ensure adequate sedation.

-

b

Consider administering neuromuscular blockade.

-

c

Pause the ventilator so that both ventilation and gas flows stop

-

d

Clamp the tracheal tube

-

e

Separate the circuit with the HME still attached to the patient

-

f

Reverse this procedure after reconnection

-

a

Avoid disconnections. push‐twist all connections to avoid risk of accidental disconnections.

Accidental disconnection. Pause the ventilator. Clamp the tracheal tube. Reconnect promptly and unclamp the tracheal tube.

Accidental extubation. This should be managed as usual, but management should be preceded by full careful donning of PPE before attending to the patient, irrespective of clinical urgency.

Tracheostomy. This is a high‐risk procedure due to aerosol‐generation, and this should be taken into account if it is considered. It may be prudent to delay tracheostomy until active COVID‐19 disease is resolved.

Risk of blockage of heat and moisture exchange filters

Actively heated and humidified ‘wet circuits’ may be avoided after tracheal intubation to avoid viral load being present in the ventilator circuit. This will theoretically reduce risks of contamination of the room if there is an unexpected circuit disconnection. There is a risk of the filter becoming blocked if it becomes wet. This will cause blockage of the filter and may be mistaken for patient deterioration, which it also may then cause. Consider whether the HME filter is wet and blocked if there is patient deterioration or difficulty in ventilation. If the HME filter is below the tracheal tube or the catheter mount, condensed liquid may saturate the HME. This is particularly likely to occur if both an HME and a wet circuit are used simultaneously 31.

Tracheal extubation

Many ICUs routinely extubate patients’ tracheas and then use high‐flow nasal oxygen immediately for up to 24 h. This is unlikely to be desirable or feasible in patients with COVID‐19. Consequently, tracheal extubation may be delayed, unless the pressure of beds demands otherwise.

-

Efforts should be made to minimise coughing and exposure to infected secretions at this time.

-

a

Undertake appropriate physiotherapy and tracheal and oral suction as normal before extubation.

-

b

Prepare and check all necessary equipment for mask or low flow (< 5 l.min−1) nasal cannula oxygen delivery before extubation.

-

c

After extubation, ensure the patient immediately wears a facemask as well as their oxygen mask or nasal cannulae where this is practical.

-

d

During anaesthesia, drugs to minimise coughing at emergence include dexmedetomidine, lidocaine and opioids 32. The value of these is unproven in critical care and needs to be balanced against adverse impact on respiratory drive, neuromuscular function and blood pressure. For these reasons, routine use is currently unlikely.

-

e

While an SGA may be considered as a bridge to extubation to minimise coughing this involves a second procedure and the possibility of airway difficulty after SGA placement so is unlikely to be a first‐line procedure 33, 34.

-

f

Likewise, the use of an airway exchange catheter is relatively contra‐indicated in a patient with COVID‐19 due to potential coughing etc.

-

a

Airway management during cardiac arrest

The UK Resuscitation Council has published statements on the management of cardiac arrest in patients with COVID‐19 35.

Airway procedures undertaken during management of cardiac arrest are likely to expose the rescuer to a risk of viral transmission. “The minimum PPE requirements to assess a patient, start chest compressions and establish monitoring of the cardiac arrest rhythm are an FFP3 facemask, eye protection, plastic apron, and gloves.” 35.

Avoid listening or feeling for breathing by placing your ear and cheek close to the patient's mouth.

In the presence of a trained airway manager early tracheal intubation with a cuffed tracheal tube should be the aim.

Before this, insertion of an SGA may enable ventilation of the lungs with less aerosol generation than facemask ventilation.

In the absence of a trained airway manager, rescuers should use those airway techniques they are trained in. Insertion of an SGA should take priority over facemask ventilation to minimise aerosol generation.

An SGA with a high seal pressure should be used in preference to one with a low seal. This will usually be a second‐generation SGA where available.

Airway management for anaesthesia

While it is beyond the scope of this document to define which patients need precautions, it is worth noting that patients may be asymptomatic with COVID‐19 but infective 36, 37, 38, 39, though symptomatic patients are more likely to pose a risk of transmission. During an epidemic, there should be a very low threshold for considering a patient at risk of being infective and it may become necessary to treat all airway interventions as high risk.

Decisions around airway management should be undertaken using the fundamental principles described above.

Airway management should be safe, accurate and swift.

There is likely to be a lower threshold for use of an SGA over facemask ventilation and also a lower threshold for tracheal intubation.

If using an SGA, spontaneous ventilation may be preferred to controlled ventilation, to avoid airway leak.

Drug choices may differ from when intubating a patient with critical illness and, in particular if the patient is not systemically unwell, ketamine may not be chosen as the induction agent.

-

Note that tracheal intubation is associated with more coughing at extubation than when an SGA is used. Avoiding this may be by

-

a

Use of an SGA instead of tracheal intubation

-

b

Changing a tracheal tube to an SGA before emergence

-

c

Use of i.v. or intracuff lidocaine; i.v. dexmedetomidine; opioids (e.g. fentanyl, remifentanil) before extubation.

-

a

Conclusions

The management of patients with known or suspected COVID‐19 requires specific considerations to safety for staff and patients. Accuracy is critical, and clinicians should avoid unreliable, unfamiliar or repeated techniques during airway management, thus enabling it to be safe, accurate and swift. Swift care means that it is timely, without rush and similarly without delay. We have highlighted principles that may achieve these goals, but the details of these principles may be subject to change as new evidence emerges.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. A COVID‐19 airway trolley and sample contents.

Appendix S2. Principles of airway management in a COVID‐19 patient. Reproduced with permission of Dr A. Chan. Department of anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Chinese University Hong Kong 26.

Appendix S3. Tracheal intubation details to be displayed in or at entrance to the patient's room. (Courtesy Royal United Hospital, Bath)

Appendix S4. Difficult tracheal intubation plan for communication between staff. (Courtesy Royal United Hospital, Bath)

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was reviewed by N Chrimes, L Duggan, F Kelly, J Nolan and members of the five bodies of the core COVID‐19 group. KE is an Editor for Anaesthesia. Thanks to Dr A Georgiou and Dr S Gouldson for contributions to the checklist. No external funding or other competing interests declared.

Contributor Information

T. M. Cook, Email: timcook007@gmail.com, @doctimcook.

K. El‐Boghdadly, @elboghdadly.

References

- 1. Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. Detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 in different types of clinical specimens. Journal of the American Medical Association 2020. Epub ahead of print 11 March. 10.1001/jama.2020.3786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of HCoV‐19 (SARS‐CoV‐2) compared to SARS‐CoV‐1. New England Journal of Medicine 2020. Epub ahead of print 13 March. 10.1101/2020.03.09.20033217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel Coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Journal of the American Medical Association 2020. Epub ahead of print 7 February. 10.1001/jama.2020.1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak in China. Summary of a report of 72,314 Cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Journal of the American Medical Association 2020. Epub ahead of print 24 February. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. The COVID‐19 Task force of the Department of Infectious Diseases and the IT Service Istituto Superiore di Sanità .Integrated surveillance of COVID‐19 in Italy. 2020. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/bollettino/covid-19-infografica_eng.pdf (accessed 13/03/2020).

- 6. Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus disease 2019 in China. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020. Epub ahead of print 28 February. 10.1056/nejmoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheung JCH, Ho LT, Cheng JV, Cham EYK, Lam KN. Staff safety during emergency airway management for COVID‐19 in Hong Kong. Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2020. Epub ahead of print 24 February. 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30084-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Public Health England . COVID‐19: infection prevention and control guidance. 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-wn-cov-infection-prevention-and-control-guidance#mobile-healthcare-equipment (accessed 13/03/2020).

- 9. Tran K, Cimon K, Severn M, Pessoa‐Silva CL, Conly J. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e35797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Respiratory Therapy Group, Chinese Medical Association Respiratory Branch . Expert consensus on respiratory therapy related to new Coronavirus infection in severe and critical patients. Chinese Journal of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Medicine 2020, 17 Epub ahead of print. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001–0939.2020.0020. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leung CCH, Joynt GM, Gomersall CD, et al. Comparison of high‐flow nasal cannula versus oxygen face mask for environmental bacterial contamination in critically ill pneumonia patients: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Hospital Infection 2019; 101: 84–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Renda T, Corrado A, Iskandar G, Pelaia G, Abdalla K, Navalesi P. High‐flow nasal oxygen therapy in intensive care and anaesthesia. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2018; 120: 18–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nicolle L. SARS safety and science. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia 2003; 50: 983–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Loeb M, McGeer A, Henry B, et al. SARS among critical care nurses, Toronto. Emergency Infectious Diseases 2004; 10: 251–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Intensive Care Society . COVID‐19 Information for ICS Members. 2020. https://www.ics.ac.uk/COVID19.aspx?hkey=d176e2cf-d3ba-4bc7-8435-49bc618c345a&WebsiteKey = 10967510-ae0c-4d85-8143-a62bf0ca5f3c (accessed 13/03/2020).

- 16. Casanova LM, Rutala WA, Weber DJ, Sobsey MD. Effect of single‐ versus double gloving on virus transfer to health care workers’ skin and clothing during removal of personal protective equipment. American Journal of Infection Control 2012; 40: 369–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) patients. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia 2020. Epub ahead of print 12 February. 10.1007/s12630-020-01591-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li Y, Huang X, Yu IT, Wong TW, Qian H. Role of air distribution in SARS transmission during the largest nosocomial outbreak in Hong Kong. Indoor Air 2005; 15: 83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nolan JP, Kelly FE. Airway challenges in critical care. Anaesthesia 2011; 66 (Suppl. 2): 81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Higgs A, McGrath BA, Goddard C, et al. Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2018; 120: 323–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Royal College of Anaesthetists . Capnography: No trace = Wrong place. 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t97G65bignQ (accessed 13/03/2020).

- 22. Cook TM, Harrop‐Griffiths WHG. Capnography prevents avoidable deaths. British Medical Journal 2019; 364: l439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chief Medical Officers of Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, England, National Medical Director NHSE/I, General Medical Council. Joint statement: Supporting doctors in the event of a Covid‐19 epidemic in the UK. 2020. https://www.gmc-uk.org/news/news-archive/supporting-doctors-in-the-event-of-a-covid19-epidemic-in-the-uk (accessed 13/03/2020).

- 24. Public Health England . Environmental decontamination, in COVID‐19: infection prevention and control guidance. 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-wn-cov-infection-prevention-and-control-guidance#decon (accessed 13/03/2020).

- 25. De JA, Molinari N, Terzi N, et al. Early identification of patients at risk for difficult intubation in the intensive care unit: development and validation of the MACOCHA score in a multicenter cohort study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2013; 187: 832–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chan A. Department of anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Chinese University Hong Kong. 2020. https://www.aic.cuhk.edu.hk/covid19 (accessed 13/03/2020).

- 27. Chrimes N. The Vortex approach. 2016. http://vortexapproach.org (accessed 13/03/2020).

- 28. Cook TM. The cricoid debate – balancing risks and benefits. Anaesthesia 2016; 71: 721–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fei M, Blair JL, Rice MJ, et al. Comparison of effectiveness of two commonly used two‐hand mask ventilation techniques on unconscious apnoeic obese adults. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2017; 118: 618–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Keller C, Brimacombe J, Kleinsasser A, Brimacombe L. The Laryngeal Mask Airway ProSeal as a temporary ventilatory device in grossly and morbidly obese patients before laryngoscope‐guided tracheal intubation. Anesthesia and Analgesia 2002; 94: 737–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Authority . Risk of using different airway humidification devices simultaneously. 2015. NHS/PSA/W/2015/012. December 2015. https://www.england.nhs.uk/patientsafety/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2015/12/psa-humidification-devices.pdf (accessed 13/03/2020).

- 32. Tung A, Fergusson NA, Ng N, Hu V, Dormuth C, Griesdale DEG. Medications to reduce emergence coughing after general anaesthesia with tracheal intubation: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2020; 124: 480–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Glaisyer HR, Parry M, Lee J, Bailey PM. The laryngeal mask airway as an adjunct to extubation on the intensive care unit. Anaesthesia 1996; 51: 1187–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Laver S, McKinstry C, Craft TM, Cook TM. Use of the ProSeal LMA in the ICU to facilitate weaning from controlled ventilation in two patients with severe episodic bronchospasm. European Journal of Anaesthesiology 2006; 23: 977–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Resuscitation Council . Resuscitation Council UK Statement on COVID‐19 in relation to CPR and resuscitation in healthcare settings. 2020. https://www.resus.org.uk/media/statements/resuscitation-council-uk-statements-on-covid-19-coronavirus-cpr-and-resuscitation/covid-healthcare (accessed 13/03/2020).

- 36. Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID‐19. Journal of the American Medical Association 2020. Epub ahead of print 21 February. 10.1001/jama.2020.2565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P. Transmission of 2019‐nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. New England Journal of Medicine 2020; 382: 970–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tong ZD, Tang A, Li KF. Potential pre‐symptomatic transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2, Zhejiang Province, China, 2020. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2020. Epub ahead of print 3 March. 10.3201/eid2605.200198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nishiura H, Linton NM, Akhmetzhanov AR. Serial interval of novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) infections. MedRxiv preprint 2020. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.02.03.20019497v2.full.pdf (accessed 13/03/2020).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. A COVID‐19 airway trolley and sample contents.

Appendix S2. Principles of airway management in a COVID‐19 patient. Reproduced with permission of Dr A. Chan. Department of anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Chinese University Hong Kong 26.

Appendix S3. Tracheal intubation details to be displayed in or at entrance to the patient's room. (Courtesy Royal United Hospital, Bath)

Appendix S4. Difficult tracheal intubation plan for communication between staff. (Courtesy Royal United Hospital, Bath)