Abstract

Introduction

Similar symptoms, comorbidities and suboptimal diagnostic tests make the distinction between different types of dementia difficult, although this is essential for improved work‐up and treatment optimization.

Methods

We calculated temporal disease trajectories of earlier multi‐morbidities in Alzheimer's disease (AD) dementia and vascular dementia (VaD) patients using the Danish National Patient Registry covering all hospital encounters in Denmark (1994 to 2016). Subsequently, we reduced the comorbidity space dimensionality using a non‐linear technique, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

Results

We found 49,112 and 24,101 patients that were diagnosed with AD or VaD, respectively. Temporal disease trajectories showed very similar disease patterns before the dementia diagnosis. Stratifying patients by age and reducing the comorbidity space to two dimensions, showed better discrimination between AD and VaD patients in early‐onset dementia.

Discussion

Similar age‐associated comorbidities, the phenomenon of mixed dementia, and misdiagnosis create great challenges in discriminating between classical subtypes of dementia.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, comorbidities, dementia, disease trajectories, electronic health records, mixed dementia, vascular dementia

1. INTRODUCTION

Dementia is often associated with numerous comorbidities, defined as diseases that co‐occur on top of a primary disease. 1 Dementia patients have significantly more comorbidities compared to matched controls without dementia, 2 , 3 but studies do not agree on which comorbidities are more or less prevalent in dementia patients. 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 Dementia patients with comorbidities present with a higher rate of cognitive decline; 8 , 9 hence modification of lifestyle and treatment of comorbidities have beneficial effects on cognition and could delay or even prevent the onset of dementia. 10 A large part of the literature does not stratify dementia patients into subtypes, and it is therefore not fully clear whether there are different comorbidity patterns in different types of dementia.

The two most common types of dementia are Alzheimer's disease (AD), which constitutes around 60% of dementia cases and vascular dementia (VaD) with around 20%. 11 Although both types of dementia are associated with similar symptoms, the pathological mechanisms are very different. While VaD is caused by a reduced blood supply to the brain due to deteriorating blood vessels, AD is characterized by synapse loss, neuronal atrophy, and an abnormal accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) protein resulting in senile plaques, which can disrupt signals between neurons and cause inflammation. 12 Furthermore, hyperphosphorylated tau proteins inside the neurons form neurofibrillary tangles causing unstable microtubules and eventually neuronal death. 12 The diagnostic process to evaluate the underlying cause of dementia can be challenging and inefficient making it difficult to differentiate between types of dementia. 12 Additionally, dementia often show more than one underlying pathology, which is known as mixed dementia (MD). The most common form being a combination of AD pathology with vascular components from VaD. 13 The only definitive diagnose is after autopsy.

Although no cure for the underlying illness of dementia exists, medication can attenuate symptoms by reducing the breakdown of acetylcholine, thereby increasing the concentration of the neurotransmitter in AD patients. 14 This type of medication has shown limited or no effect for patients with other types of dementia, including VaD. 15 In patients with VaD, treatment of the underlying cause of dementia can help prevent further brain damage and may slow down the progression of dementia. 16 Currently medications for AD and VaD only show modest clinical benefits for patients with MD. 17 Therefore, the distinction between the types of dementia is essential for optimal treatment. Early detection of dementia allows for an improvement of lifestyle choices, like vascular risk factors, poor nutrition, or lack of cognitive stimulation. Patterns in comorbidities and temporal trajectories can inform about different, as well as shared, pathophysiological cascades of AD and VaD and understanding such interactions between comorbidities and dementia might disclose new and improved strategies for treating or preventing dementia.

We identify frequent temporal trajectories of diseases to characterize the similarities and differences in prior disease history of AD and VaD patients, respectively. The temporal disease history and comorbidities of patients with dementia may provide novel insights for earlier detection, potential risk factors, and discrimination between different types of dementia.

2. METHODS

2.1. The Danish National Patient Registry

We take advantage of a population‐wide disease registry, the Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) that in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD‐10) period covers all hospital encounters in Denmark from 1994 to 2016 and includes >7 million patients and >100 million encounters. The registry contains administrative information such as primary and secondary diagnoses coded in the ICD‐10 terminology, as well as other information on procedures and treatments.

2.2. ICD‐10 terminology

The ICD‐10 terminology hierarchically organizes diseases, with the highest level consisting of 21 disease chapters (eg, Chapter V: Mental and behavioural disorders). Each of the chapters is subdivided into several blocks that cover a range of specific diseases (eg, F00‐F09: Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders). These are further subdivided into individual diseases (eg, F00: Dementia in Alzheimer disease). This third level is used for all comorbidity and trajectory analyses to be medically relevant and not to reduce statistical power by including too few patients. In the ICD‐10 system dementia can be recorded as one of four different diagnosis codes using the third level; F00 “Dementia in Alzheimer disease,” F01 “Vascular dementia,” F02 “Dementia in other diseases classified elsewhere,” or F03 “Unspecified dementia.” As F02 “Dementia in other diseases classified elsewhere” includes several different types of dementia, we only analyze comorbidities and temporal disease trajectory patterns of patients diagnosed with F00 or F01. Unfortunately, MD is not considered in the ICD‐10 coding system.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic review: Using PubMed, we reviewed articles investigating comorbidities in dementia patients. The majority of studies did not differentiate between types of dementia and therefore, we lack knowledge about distinctive comorbidity‐patterns prior to Alzheimer's disease (AD) dementia and vascular dementia (VaD).

Interpretation: We present an unbiased analysis of earlier multi‐morbidities in AD and VaD patients to separate the general aging components from those that are specific for dementia subtypes. Temporal disease trajectories before the dementia diagnosis showed very similar disease history; however, stratifying patients by age‐of‐onset and reducing the comorbidity space to two dimensions, discriminated between AD and VaD patients in early onset dementia.

Future directions: Misdiagnosis of dementia patients and the fact that many patients show pathology of both AD and VaD (mixed dementia) complicates the diagnostic process. There is an urgent need for better discrimination between subtypes of dementia to ensure the optimal management and treatment of patients.

2.3. Identifying AD and VaD patients

Often patients are diagnosed with several different dementia codes in registries, and these codes can occur several times during different admissions. Thus, we identify likely AD patients as any patient diagnosed with (Figure S1 in supporting information):

F00 “Dementia in Alzheimer disease,” but not F03 “Unspecified dementia”

F03 “Unspecified dementia” and F00 “Dementia in Alzheimer disease” on the same day

F03 “Unspecified dementia” and subsequently F00 “Dementia in Alzheimer disease”

F00 “Dementia in Alzheimer disease,” followed by F03 “Unspecified dementia,” but also diagnosed with G30 “Alzheimer disease”

Patients are excluded if they are diagnosed with F01 “Vascular dementia” in addition to F00 “Dementia in Alzheimer disease.”

We similarly defined VaD patients as any patient diagnosed with (Figure S1):

F01 “Vascular dementia,” but not F03 “Unspecified dementia”

F03 “Unspecified dementia” and F01 “Vascular dementia” on the same day

F03 “Unspecified dementia” and subsequently F01 “Vascular dementia”

Patients are excluded if they are diagnosed with F00 “Dementia in Alzheimer disease” in addition to F01 “Vascular dementia.”

2.4. Relative risk assessment for comorbidities and creation of temporal disease trajectories

Trajectories were created using a previously published method. 18 All patients defined as AD or VaD using the above‐mentioned criteria are extracted. Disease pairs that co‐occur more often together in each of the dementia groups are identified (Figure S2 in supporting information). The relative risk (RR) is used to evaluate the strength of each disease pair association. For example, the number of AD patients with disease A is calculated (Cexposed). N = 10,000 randomly selected patients with disease A are matched to the AD patients with disease A by age, sex, type of hospital encounter, and discharge week and used as a control group. Subsequently, occurrences of disease B in AD patients and the matched control group are calculated (C1…CN), and the RR can be described as:

Using this approach, we identify disease pairs that co‐occur significantly more together in AD or VaD patients compared to the matched control population. Then, a binomial test is used to determine whether significantly more patients had disease A before disease B, or the other way around (Figure S2). Disease pairs with a significant directionality are merged into longer temporal disease trajectories of three or more consecutive diseases. A patient follows a linear trajectory only if their diseases were assigned in the order specified by the trajectory. A given set of different, linear temporal trajectories can be visualized as a disease progression network, whereby edges linking directed disease pairs show how frequently alternative disease paths are followed over time (Figure S2). For additional detail on the method, see earlier work. 18 , 19 , 20

2.5. Reducing dimensionality of the comorbidity space of dementia patients

To better discriminate between AD and VaD patients, we implemented different restrictions to ensure that patients had a disease history before the dementia diagnosis. We, therefore, reduced the comorbidity space of dementia patients using three different cut‐offs of minimum 3, 5, or 10 years of disease history before the dementia diagnosis, respectively. All diagnoses given from the first diagnosis in the registry to the first dementia diagnosis were recorded. The final matrix includes all AD and VaD patients and all their diagnoses in the registry. Four submatrices separated the patients according to age at the first dementia diagnosis. The four patient groups included patients diagnosed with dementia: (1) between 40 and 50 years old, (2) between 59 and 61 years old, (3) at 70 years old, and (4) at 80 years old. We wanted to analyze comorbidities for patients with age‐of‐dementia‐onset at 50, 60, 70, and 80, but as few patients are diagnosed with early onset dementia the sizes of the age intervals differ to include at least 100 patients. To uncover if a combination of comorbidities could discriminate AD and VaD patients, we reduced the comorbidity space to two dimensions using uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP). 21 UMAP is a non‐linear technique for dimensionality reduction that strives to learn the manifold structure of a dataset and keep the essentials of the structure in a lower dimensionality embedding. 21 UMAP is also used to visualize the reduced two‐dimension space of AD and VaD patients. To evaluate how well we can separate the AD and VaD patients in the reduced comorbidity space, we applied K‐means clustering to predict the type of dementia. The clustering was evaluated with both the Adjusted Rand Index 22 and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC). 23

2.6. Data and materials approval

This study has been approved by the Danish Data Registration Agency, Copenhagen (ref: SUND‐2016‐83) and the Danish Health Authority, Copenhagen (refs: FSEID‐00001627 and FSEID‐00003092).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Discriminating AD and VaD patients

Out of the >7 million patients in the national registry, a total of 171,607 patients are diagnosed with one or more of the four dementia codes (Figure 1). We defined likely AD or VaD patients based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria described above (section 2.3 . Identifying AD and VaD patients) and Figure S1 giving rise to 49,112 AD patients and 24,101 VaD patients. Patient characteristics for each of these groups are shown in Table 1. AD patients were more frequently women and the age of first dementia diagnose is higher in AD patients. 20 Additionally, VaD patients have a larger disease burden with, on average, two additional diseases in the registry. The distribution of the dementia diagnoses throughout the period of the registry shows that the “Unspecified dementia” diagnosis is the most common and the number of AD diagnoses are increasing at a steady rate not affected by slight changes in diagnostic criteria (Figure S3 in supporting information).

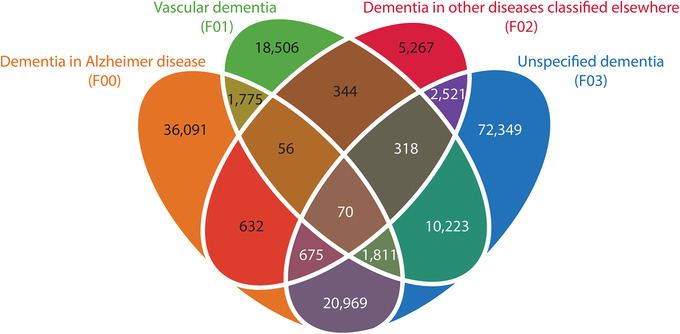

FIGURE 1.

Venn diagram with overlap of dementia diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Registry. A significant number of patients are only diagnosed with “unspecified dementia.” The patients, for whom a specification is recorded, are often diagnosed with more than one type of dementia

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics of AD and VaD patients

| Demographics | Dementia in Alzheimer's disease (AD) | Vascular dementia (VaD) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n) | 49,112 | 24,101 |

| Male (n) | 17,129 (34.88%) | 11,298 (46.88%) |

| Female (n) | 31,983 (65.12%) | 12,803 (53.12%) |

| Age at the first dementia diagnose (mean SD) | 80.32 8.24 | 79.12 9.31 |

| Number of patients that died (n) | 34,702 (70.66%) | 19,850 (82.36%) |

| Age at death (mean SD) | 84.99 7.29 | 83.23 7.98 |

| Average number of dementia diagnoses (n) | 2.32 | 1.98 |

| Average number of diagnoses in the registry (n) | 13.97 | 16.36 |

The average number of diagnoses is calculated based on unique level three ICD‐10 diagnoses present in the registry. All diagnoses from chapter XXI “Factors influencing health status and contact with health services” and chapter XV “Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium” are excluded. SD, standard deviation.

3.2. Temporal disease trajectories and networks for AD and VaD

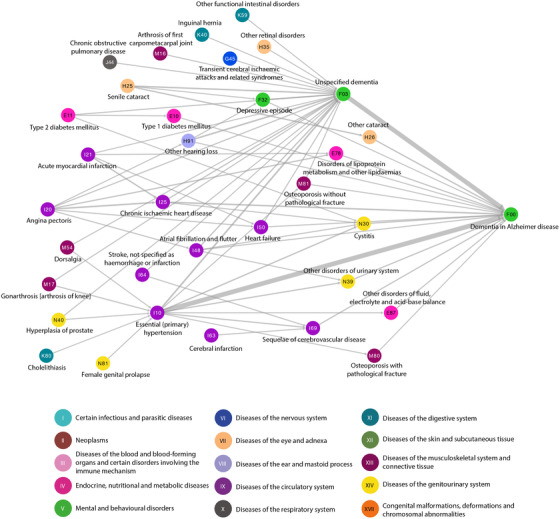

Temporal disease trajectories were created for all AD and VaD patients, respectively. The group of 49,112 AD patients displayed 50 significant directional trajectories consisting of three consecutive diseases, where at least 1 out of 100 AD patients followed the entire trajectory (491 patients). The different linear temporal trajectories can be visualized as a disease progression network with edges linking directed disease pairs, showing how frequently alternative disease paths are followed over time (Figure 2). Many trajectories contain F03 “Unspecified dementia” and subsequently F00 “Dementia in Alzheimer disease.” E10 “Type I diabetes mellitus” and E11 “Type II diabetes mellitus” are common paths toward a dementia diagnosis, as are cardiovascular diseases like I10 “Hypertension,” I20 “Angina pectoris,” and I50 “Heart failure.” Furthermore, aging‐associated diseases, like cataracts, hearing loss, and osteoporosis are common comorbidities in AD patients (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Temporal disease trajectory network of diagnoses given before F00 “Dementia in Alzheimer disease.” Fifty significant trajectories with three consecutive diseases that at least 1 out of 100 (491) Alzheimer's disease patients follow are combined in the disease progression network. The thickness of the edges linking disease pairs indicates how frequently disease paths are followed over time. Diseases are colored according to International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD‐10) chapters as indicated

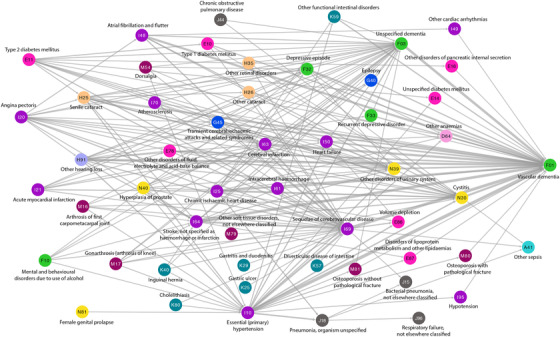

The group of 24,101 VaD patients displayed 215 significant directional trajectories consisting of three consecutive diseases, where at least 1 out of 100 VaD patients followed the entire trajectory (241 patients). A similar disease progression network shows alternative paths over time followed by at least 1 out of 100 VaD patients (Figure 3). As in AD, patients are diagnosed with F03 “Unspecified dementia” before the diagnosis of F01 “Vascular dementia” and E10 “Type I diabetes mellitus” and E11 “Type II diabetes mellitus” and cardiovascular diseases like I10 “Hypertension,” I20 “Angina pectoris,” and I50 “Heart failure” are seen to be common disease paths toward VaD.

FIGURE 3.

Temporal disease trajectory network of diagnoses given before F01 “Vascular dementia.” Two hundred fifteen significant trajectories with three consecutive diseases that at least 1 out of 100 (241) vascular dementia patients follow are combined in the disease progression network. The thickness of the edges linking disease pairs indicates how frequently disease paths are followed over time. Diseases are coloured according to International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD‐10) chapters. For the color scheme see Figure 2

All diagnoses that present before AD in the temporal disease trajectory network are likewise diagnosed before the VaD diagnosis showing identical temporal patterns. The VaD trajectory network includes additional 19 diagnoses, for example, F10 “Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol,” F33 “Recurrent depressive disorder,” I61 “Intracerebral haemorrhage,” and I70 “Atherosclerosis.”

3.3. Assessing differences in comorbidities and RRs for AD and VaD

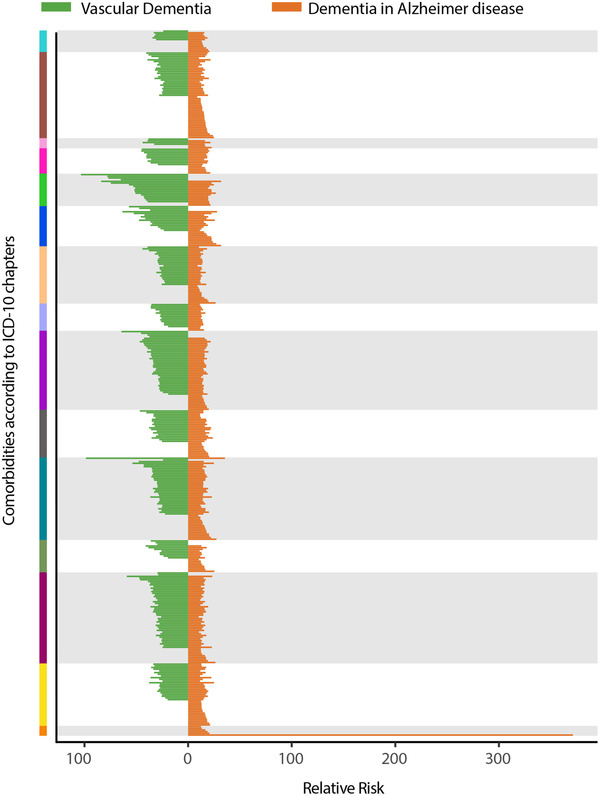

In total, 398 comorbidities appear before AD and 284 comorbidities present before VaD. The far majority (265) of the comorbidities are seen in both AD and VaD patients (Figure 4 and Table S1 in supporting information). The RR is consistently higher in VaD patients compared to AD patients. The comorbidity with the highest RR for AD is Q90 “Down syndrome” (RR = 371) and F19 “Mental and behavioural disorders due to multiple drug use and use of other psychoactive substances” (RR = 103) for VaD (Figures S4 and S5 in supporting information). In general, diseases from chapter V “Mental and behavioural disorders” and chapter VI “Diseases of the nervous system” have a high RR for both AD and VaD (Table S1).

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of significant comorbidities of vascular dementia (VaD) and Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients. All VaD comorbidities are indicated with a green line and all AD comorbidities in orange. The color on the y‐axis indicates which International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD‐10) chapter the significant comorbidity belongs to. A green line in the purple area indicates a VaD comorbidity for chapter IX “Diseases of the circulatory system.” When both a green and an orange line are present, the comorbidity is significant in both AD and VaD patients. The x‐axis shows the relative risk (RR) for each comorbidity. For specification of all significant comorbidities and RRs, see Table S1. For the color scheme of ICD‐10 chapters see Figure 2

Majority of the comorbidities with high RRs are from the same ICD‐10 chapters. Therefore, taking advantage of temporal disease trajectories, significant specific comorbidities, and their associated RRs, cannot easily discriminate between VaD and AD patients.

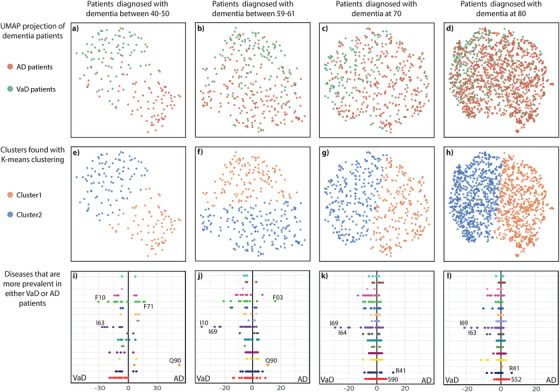

3.4. Dimensionality reduction of the comorbidity space of dementia patients

To discriminate between AD and VaD, all dementia patients with a minimum of 3, 5, or10 years of disease history, respectively, were stratified into four age groups. Between the groups, a large variation in the size of the comorbidity space is observed with longer disease history and older age resulting in larger comorbidity space as expected (Table S2 in supporting information). The comorbidity space was reduced to two dimensions using the non‐linear dimensionality reduction algorithm, UMAP. 21 In the two‐dimensional comorbidity space, AD and VaD patients separate well in the case of early onset dementia with first diagnosis between age 40 and 50 (MCC = 0.69 for the analysis with 10 years of previous disease history; Figure 5A and Figures S6 and S7a and Table S2 in supporting information). Diagnoses that are more prevalent in AD patients include Q90 “Down syndrome,” F71 “Moderate mental retardation,” and F79 “unspecified mental retardation” while F10 “Mental and behavioural disorders due to the use of alcohol,” I63 “Cerebral infarction,” I69 “Sequelae of cerebrovascular disease,” and I64 “Stroke” are more prevalent in VaD patients (Figure 5I, and Figures S6‐S7i and Table S3 in supporting information). Increasing age at the first dementia diagnosis causes difficulties in discriminating between the subtypes (Figure 5B‐D and Figures S6‐S7b‐d) and several aging‐associated diseases appear in both types of dementia (all dots move closer to the middle; Figure 5I‐L and Figures S6‐S7i‐l). For patients diagnosed with dementia at the age of 80 only a few diagnoses are more prevalent in VaD and they include I69 “Sequelae of cerebrovascular disease,” I63 “Cerebral infarction,” I10 “Hypertension,” and I64 “Stroke.”

FIGURE 5.

Reduced dimensionalities of comorbidity spaces for age‐of‐onset stratified dementia patients. All dementia patients with at least 10 years of disease history were grouped according to their age at first dementia diagnosis. The upper panel (A‐D) show Alzheimer's disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD) patients in the comorbidity space reduced to two dimensions with UMAP. One dot corresponds to one patient. All green dots indicate VaD patients, while all orange dots indicate AD patients. Separation of VaD and AD patients becomes more difficult as age at first diagnosis increases. The middle panel (E‐H) shows the groups identified by K‐means clustering. One dot corresponds to one patient. All orange dots are in cluster 1, while all blue dots are in cluster 2. All clusters are evaluated with Adjusted Rand Index and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (see Table S2). The lower panel (I‐L) displays a comparison of disease prevalence in each group of dementia patients. Each dot indicates a disease and they are colored according to International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD‐10) chapter (for color scheme see Figure 2). All dots to the left and the right of the middle are more prevalent in VaD patients and AD patients, respectively. The two diseases with the largest difference between the groups are highlighted on the figure. For all disease prevalence's see Table S3. F03 = “Unspecified dementia”; F10 = “Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol”; F71 = “Moderate mental retardation”; I10 = “Essential (primary) hypertension”; I63 = “Cerebral infarction”; I64 = “Stroke, not specified as hemorrhage or infarction”; I69 = “Sequelae of cerebrovascular disease”; Q90 = “Down syndrome”; R41 = “Other symptoms and signs involving cognitive functions and awareness”; S52 = “Fracture of forearm”; S90 = “Superficial injury of ankle and foot”

4. DISCUSSION

We took advantage of a national disease registry that covers all hospital encounters in Denmark for >2 decades to investigate disease progression patterns in two different types of dementia—AD and VaD. We found a broad range of temporal disease trajectories for patients with dementia illustrating numerous disease paths that eventually can lead to AD or VaD, respectively. These analyses of disease paths before dementia manifest result from an essentially unbiased scrutiny of all hospital diagnoses, meaning that all diseases that appear as significant directional comorbidities in patients diagnosed with dementia are included. There is a substantial overlap in disease paths leading to both AD and VaD, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cataract, and osteoporosis emphasizing that many risk factors are associated with both AD and VaD.

Several other studies have identified comorbidities in dementia patients, but none have systematically compared comorbidities between AD and VaD patients in population‐wide data. Here, we find several diseases from chapter V “Mental and behavioural disorders” and chapter VI “Diseases of the nervous system” with high RRs for both AD and VaD. Additionally, we identify cerebrovascular diseases from chapter IX “Diseases of the circulatory system” that are known to be risk factors for VaD. 24 , 25 We confirm well‐known comorbidities associated to dementia such as cardiovascular diseases, 2 , 4 , 26 mental disorders such as depression, sleep disorders, and bipolar disorder, 2 , 4 and diabetes, which is a highly debated comorbidity in AD. 2 , 4 , 27 , 28 , 29 VaD often arises as a consequence of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases, which are also associated with many other comorbidities and complications 30 , 31 and therefore could explain the more expansive disease trajectory of VaD patients. Furthermore, VaD patients have twice as many hospital days as AD patients and higher hospitals cost suggesting more or worse comorbidities. 32

Stratification of dementia patients into age‐of‐onset groups showed discrimination of AD and VaD patients with early onset dementia (40 to 50 years old). However, the prevalent diseases in AD and VaD with early onset are known risk factors of early onset dementia, including Down syndrome, alcohol‐related diagnoses, and cerebrovascular diseases. 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 Early onset AD can be caused by familial genetic mutations, 38 although some cases are not, including Down syndrome, and confirming and discovering comorbidities associated with early onset AD can be beneficial to prevention and treatment strategies. In early onset dementia many diseases have very different prevalence between AD and VaD, while patients diagnosed with dementia at an older age have more aging‐associated diseases that are prevalent in both types of dementia. This pattern is seen both when including 3, 5, or 10 years of prior disease history for dementia patients, even though the MCC score in general is higher the more disease history that is available. The latter provides quantitative evidence for concluding that longer term disease development is etiologically important.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This study used diagnosis codes from the DNPR that covers all hospital encounters in Denmark. Patients exclusively diagnosed by their general practitioner are not included in DNPR. Therefore, it might be that only patients with more severe dementia or other severe comorbidities are included in our analyses. However, previous studies showed that dementia diagnosed in the Danish secondary health sector covered 66% of the expected prevalence of dementia. 39 DNPR covers diagnoses from the entire country for >20 years, which provides the opportunity to create longer, temporal disease trajectories. Moreover, all diagnoses given at the hospitals are taken into consideration and thereby preselected diseases or risk factors do not limit the analyses. However, the disease associations elucidated by the trajectory analyses cannot necessarily be considered causal. The different disease associations could be due to a variety of causes, including cardiovascular diseases as dementia risk factors, complications such as depression or falls, or age‐related comorbidities like osteoporosis. 6

The difficulties of distinguishing between types of dementia are seen in DNPR as several patients are diagnosed with different types of dementia (Figure 1). Accuracy of the AD diagnosis varies between studies with a median sensitivity of 85% and median specificity of 58%. 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 The AD diagnosis was evaluated in 526 subjects from the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Centre and autopsies found that 88 of them did not meet the neuropathologic criteria of an AD diagnosis, corresponding to a misdiagnosis percentage of 17%. 40 A Danish study in the secondary health sector found that correct types of dementia were diagnosed in only 35% of dementia cases, with the AD diagnosis having the best positive predictive power (PPV) of 87%, while the PPV for VaD was 21%. 42 Even though we identified patients with likely AD of VaD the large percentage of potentially incorrect diagnoses can have substantial influence on our results. Thus, more stringent diagnostic criteria, for especially VaD, could likely have improved the analysis. We cannot further validate the criteria of dementia as we have no information on cognitive decline or behavioral symptoms in the registry. However, we observed that 80% of the VaD cohort were diagnosed with a cerebrovascular disease (ICD‐10 codes: I60‐I69) or have had an MRI or CT scan of cerebrum (procedure codes: UXCA00, UXMA00, WCBCPXYXX, and WCBMPXYXX). The majority of the VaD patients that have not had any of these codes are diagnosed with dementia before year 2000. Hence these are the patients with only few years of disease history before the dementia diagnosis and therefore they could possibly have had tests or other diseases that are not included in the registry.

In 2011 the diagnostic criteria for AD changed, expanding the scope for what is considered probable AD and including enrichment of certain biomarkers to confirm the AD diagnosis. 45 , 46 If no biomarkers are identified the diagnosis of AD is justified by excluding other types of dementia and related comorbidities. 46 However, the growth in AD diagnoses at the Danish hospitals is essentially the same before and after 2011 (Figure S3). The diagnostic criteria for VaD changed in 2015, 47 but as our analysis ends in 2016 this change cannot have a strong influence on the analysis.

MD is not considered in the ICD‐10 coding system and there is no consensus on how MD should be coded using ICD‐10 in the clinical practice. In the new version of ICD to be adopted from January 1, 2022, ICD‐11, Alzheimer disease dementia, mixed type, with cerebrovascular disease (6D80.2), has been included. Other studies have found that the prevalence of certain comorbidities, like atherosclerosis, hypertension, and diabetes, is lower in MD patients than in VaD patients but higher in MD patients than in AD patients. 48 Thus, it seems as though it is not only the pathology of MD patients that is a mixture of AD and VaD, but also their phenotypic comorbidity profile that is mixed. This study showed that some AD and VaD patients had very similar comorbidities supporting a potential profile of mixed dementia. Autopsies demonstrate that 46% of AD patients have mixed pathologies emphasizing that dementia is often associated with several different, mixed pathologies. 49 , 50 Additional research is needed and should include laboratory values, images, and free text for these patients to provide more knowledge and to discover the true phenotype and underlying cause of dementia.

Collectively, this study provides an overview of the prior disease history for AD and VaD, respectively. Discovering relevant comorbidities associated to dementia could reveal shared mechanisms between disorders and potentially provide insight into the different pathogeneses of the two kinds of dementia. In early onset of dementia patients, specific comorbidity patterns can discriminate between AD and VaD though many AD and VaD patients displayed similar comorbidities possibly suggesting an underestimated incidence of mixed dementia. Several cases of dementia might not be diagnosed correctly creating an urgent need for more research in discrimination between types of dementia.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

SB reports fees from Intomics A/S and Proscion A/S outside this work.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding: This work was supported by Novo Nordisk Foundation (grant agreement NNF14CC0001), Innovation Fund Denmark (ref. 5184‐00102B), MedBioinformatics EU Horizon 2020 (grant agreement 634143) and ROADMAP ‐ H2020‐JTI‐IMI2‐2015‐06‐03 (grant agreement 116020).

Jørgensen IF, Aguayo‐Orozco A, Lademann M, Brunak S. Age‐stratified longitudinal study of Alzheimer's and vascular dementia patients. Alzheimer's Dement. 2020;16:908–917. 10.1002/alz.12091

REFERENCES

- 1. Hu J, Thomas CE, Brunak S. Network biology concepts in complex disease comorbidities. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:615‐629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bauer K, Schwarzkopf L, Graessel E, Holle R. A claims data‐based comparison of comorbidity in individuals with and without dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14 10.1186/1471-2318-14-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhao Y, Kuo TC, Weir S, Kramer MS, Ash AS. Healthcare costs and utilization for Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer's. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang QH, Wang X, Le BuX, etal. Comorbidity Burden of Dementia: a hospital‐based retrospective study from 2003 to 2012 in seven cities in China. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33:703‐710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bunn F, Burn AM, Goodman C, etal. Comorbidity and dementia: a scoping review of the literature. BMC Med. 2014;12:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Poblador‐Plou B, Calderón‐Larrañaga A, Marta‐Moreno J, etal. Comorbidity of dementia: a cross‐sectional study of primary care older patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14 10.1186/1471-244X-14-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Subramaniam H. Co‐morbidities in dementia: time to focus more on assessing and managing co‐morbidities. Age Ageing. 2019;48:314‐315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Doraiswamy PM, Leon J, Cummings JL, Marin D, Neumann PJ. Prevalence and impact of medical comorbidity in Alzheimer's disease.J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M173‐M177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Solomon A, Dobranici L, Kareholt I, Tudose C, Lǎzǎrescu M. Comorbidity and the rate of cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer dementia. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 2011;26:1244‐1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, etal. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390:2673‐2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rizzi L, Rosset I, Roriz‐cruz M. Global epidemiology of dementia : Alzheimer's and vascular types. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karantzoulis S, Galvin JE. Distinguishing Alzheimer's disease from other major forms of dementia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11:1579‐1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jellinger KA. The enigma of mixed dementia. Alzheimer's Dement. 2007;3:40‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nordberg A, Svensson A‐L. Cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease a comparison of tolerability and pharmacology. Drug Saf. 1998;19:465‐480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perera G, Khondoker M, Broadbent M, Breen G, Stewart R. Factors associated with response to acetylcholinesterase inhibition in dementia: a cohort study from a secondary mental health care case register in London. PLoS One. 2014;9:e109484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Romãn GC. Vascular dementia: distinguishing characteristics, treatment, and prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:S296‐S304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Langa KM, Foster NL, Larson EB. Mixed dementia: emerging concepts and therapeutic implications. JAMA. 2004;292:2901‐2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jensen AB, Moseley PL, Oprea TI, etal. Temporal disease trajectories condensed from population‐wide registry data covering 6.2 million patients. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beck MK, Jensen AB, Nielsen AB, Perner A, Moseley PL, Brunak S. Diagnosis trajectories of prior multi‐morbidity predict sepsis mortality. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Westergaard D, Karuna F, Sørup H, Baldi P, Brunak S. Population‐wide analysis of differences in disease progression patterns in men and women. Nat Commun. 2019;10 10.1038/s41467-019-08475-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McInnes L, Healy J, Melville J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction 2018.

- 22. Rand WM. Objective criteria for the evaluation of clustering methods. J Am Stat Assoc. 1971;66:846‐450. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matthews BW. Comparison of the predicted and observed secondary structure of T4 phage lysozyme. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;405:442‐451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Corraini P, Henderson VW, Ording AG, Pedersen L, Horváth‐Puhó E, Sørensen HT. Long‐term risk of dementia among survivors of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Stroke. 2017;48:180‐186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jaraj D, Wikkelsø C, Rabiei K, etal. Mortality and risk of dementia in normal‐pressure hydrocephalus: a population study. Alzheimer's Dement. 2017;13:850‐857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. de Bruijn RF, Ikram MA (2014) Cardiovascular risk factors and future risk of Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Medicine, 12 (1), 10.1186/s12916-014-0130-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arnold SE, Arvanitakis Z, Macauley‐Rambach SL, etal. Brain insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer disease: concepts and conundrums. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:168‐181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miklossy J, McGeer PL. Common mechanisms involved in Alzheimer's disease and type 2 diabetes: a key role of chronic bacterial infection and inflammation. Aging. 2016;8:575‐588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abner EL, Nelson PT, Kryscio RJ, etal. Diabetes is associated with cerebrovascular but not Alzheimer neuropathology. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:882‐889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. O'Brien JT, Thomas A. Vascular dementia. Lancet. 2015;386:1698‐1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kloppenborg RP, van den Berg E, Kappelle LJ, Biessels GJ. Diabetes and other vascular risk factors for dementia: which factor matters most? A systematic review. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;585:97‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fillit H, Hill J. The costs of vascular dementia: a comparison with Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Sci. 2002;203:35‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heath CA, Mercer SW, Guthrie B. Vascular comorbidities in younger people with dementia: a cross‐sectional population‐based study of 616 245 middle‐aged people in Scotland. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:959‐964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lott IT, Head E. Dementia in Down syndrome: unique insights for Alzheimer disease research. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:135‐147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wisniewski KE, Wisniewski HM, Wen GY. Occurrence of neuropathological changes and dementia of Alzheimer's disease in Down's syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1985;17:278‐282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ritchie K, Villebrun D. Epidemiology of alcohol‐related dementia. Handb Clin Neurol. 2008;89:845‐850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Oslin DW, Cary MS. Alcohol‐related dementia: validation of diagnostic criteria. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:441‐447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2006;368:387‐403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Phung TKT, Waltoft BL, Kessing LV, Mortensen PB, Waldemar G. Time trend in diagnosing dementia in secondary care. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;29:146‐153 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Beach TG, Monsell SE, Phillips LE, Kukull W. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers, 2005‐2010. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:266‐273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Petrovitch H, White LR, Ross GW, etal. Accuracy of clinical criteria for AD in the Honolulu‐Asia Aging Study, a population‐based study. Neurology. 2001;57:226‐234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Phung TKT, Andersen BB, Kessing LV, Mortensen PB, Waldemar G. Diagnostic evaluation of dementia in the secondary health care sector. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;27:534‐542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hunter CA, Kirson NY, Desai U, Cummings AKG, Faries DE, Birnbaum HG. Medical costs of Alzheimer's disease misdiagnosis among US Medicare beneficiaries. Alzheimer's Dement. 2015;11:887‐895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gaugler JE, Ascher‐Svanum H, Roth DL, Fafowora T, Siderowf A, Beach TG. Characteristics of patients misdiagnosed with Alzheimer's disease and their medication use: an analysis of the NACC‐UDS database. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jack CRJ, Albert M, Knopman DS, etal. Introduction to the recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer Dement. 2011;7:257‐262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McKhann G, Knopman D, Chertkow H, etal. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263‐269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sachdev P, Kalaria R, O'Brien J, etal. Diagnostic criteria for vascular cognitive disorders: a VASCOG statement. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28:206‐218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Javanshiri K, Waldö ML, Friberg N, etal. Atherosclerosis, hypertension, and diabetes in Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, and mixed dementia: prevalence and presentation. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2018;65:1247‐1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Arvanitakis Z, Shah RC, Bennett DA. Diagnosis and management of dementia: review. JAMA. 2019;322:1589‐1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. The neuropathology of probable Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:200‐208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information