Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection (COVID-19) is known to induce severe inflammation and activation of the coagulation system, resulting in a prothrombotic state. Although inflammatory conditions and organ-specific diseases have been shown to be strong determinants of morbidity and mortality in patients with COVID-19, it is unclear whether preexisting differences in coagulation impact the severity of COVID-19. African Americans have higher rates of COVID-19 infection and disease-related morbidity and mortality. Moreover, African Americans are known to be at a higher risk for thrombotic events due to both biological and socioeconomic factors. In this review, we explore whether differences in baseline coagulation status and medical management of coagulation play an important role in COVID-19 disease severity and contribute to racial disparity trends within COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, race, ethnicity, coagulation, anticoagulation, thrombosis

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) disease (COVID-19) induces a prothrombotic state, resulting in the development of pathologic arterial and venous blood clots.1–4 Severe systemic inflammation often results in disturbances of hemostasis and coagulation. The systemic inflammation and dysregulated cytokine activity (often termed “cytokine storm”) associated with COVID-19 disease is likely a critical event in the development of COVID-19 coagulopathy.1,5 Patients with severe manifestations of COVID-19 often have elevated levels of D-dimer, fibrin-degradation products (FDPs) and fibrinogen, as well as low levels of antithrombin (AT). Many patients also have elevated concentrations of Factor VIII (FVIII) and von Willebrand factor (vWF).1,4 These findings are not unexpected, as many coagulation factors, including the ones listed above, are acute-phase proteins associated with the level of inflammation.6 As COVID-19 continues to spread throughout the United States, the African American community has been disproportionately affected.7 Coagulation status and predisposition to the development of coagulopathies varies between race and ethnicity, with African Americans trending toward a more prothrombotic state.8 Baseline differences in coagulation factors in conjunction with activation of the immune system and platelets likely contribute to the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 disease in African American patients.

The pathology of COVID-19 relies upon the coronavirus (CoV) spike protein (SP) binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor (ACE2R), where it then undergoes proteolytic cleavage into spike protein 1 and 2 (SP1/SP2), resulting in successful host cell infection.9 Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors are expressed in a variety of tissues, including the lungs, various parts of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the heart, and brain/central nervous system. Accordingly, the primary presentations of COVID-19 in symptomatic patients include respiratory, cardiac, GI, and neurologic signs.10–12 The range of clinical findings in COVID-19 can span the gamut from asymptomatic to severe illness, requiring intensive care unit admission and mechanical ventilation. Additionally, the severity of disease has been linked to the presence of various comorbidities. Given the organ systems for which COVID-19 has tropism (via localization of the host cell receptor expression, ACE2R), patients with preexisting pulmonary and cardiovascular conditions are at increased risk. The risk is further heightened by the fact that many of these conditions, including congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), are associated with increased levels of ACE2R expression.13–16

Although robust basic and clinical studies have yet to be published, various case series reports, clinical observations, and theories have been proposed regarding the pathogenesis of COVID-19-related coagulopathies. Upon exposure to a viral pathogen, such as SARS-CoV-2, there are multiple potential mechanisms that can trigger coagulation pathways, including leukocyte activation, complement activation, systemic inflammation, and pathological changes of infected host cells, such as endotheliitis, which may result in cellular damage and apoptosis, which may then further active inflammation and coagulation.17–20 In addition to the conditions that render specific organ systems at risk, such as COPD and asthma, systemic diseases such as diabetes, obesity, autoimmune disorders, and cancer predispose patients to severe and rapid changes to their inflammatory system and, in many cases, also predispose a patient to being in a prothrombotic state.21–25 Individuals with these preexisting conditions, along with cardiopulmonary disease, appear to be at the highest risk for development of severe COVID-19 as well as higher mortality rate.13–16

Additionally, there is mounting evidence that a major pathological finding in severe COVID-19 is the development of macrothrombi and microthrombi. Multiple recent studies have demonstrated that there is pathological blood clot formation on a systemic level, including deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolisms (PE), pulmonary microthrombi, stroke, and even thrombus formation in the placenta.26–33 Systemic thrombosis has been noted to result in acute bowel ischemia, leading to the need for emergency surgery.34,35

COVID-19 Disease Trends

A growing body of literature describes the disproportionate effect of COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality in minority populations, particularly African Americans. According to a recent report from the Chicago area, greater than 50% of COVID-19 cases and 70% of COVID-19-related deaths have been observed in African Americans, although they make up only 30% of the study population.7 Similar trends have been noted in Louisiana, Michigan, and New York City.17–18 According to a Johns Hopkins University and America Community Survey, COVID-19 rates were 3 times higher, and the death rate was at least 6 times higher, in 131 predominantly African American counties compared to infection and death rates from 2879 predominantly white counties, 6 predominantly Asian counties, and 124 predominantly Hispanic counties.36,37 Health care disparities and socioeconomic status plays a major role in this increase in morbidity and mortality. However, to assume that these 2 factors explain the totality of the racial disparities in outcomes of COVID-19 runs the risk of missing important therapeutic avenues for reducing burden of illness in these vulnerable populations. Indeed, interrogating differences in comorbid conditions and baseline abnormalities of coagulation may provide critical inroads into mitigating the higher risk of adverse outcomes in minority racial groups such as African Americans. Recent studies have shown severe pulmonary and cardiac pathology, associated with increased thrombosis, is prevalent in African Americans with severe COVID-19.26,38 Although more research into this area is needed to draw any conclusions, researchers and clinicians are beginning to take notice of the possibility of differences in baseline coagulation status, in conjunction with other variations, as potentially playing a potential role in the severity of COVID-19.38,39

Coagulation Differences Related to Race or Ancestry

Variations in coagulation activity can be dichotomized into congenital and acquired. Congenital differences in coagulation status are due to genetic differences between individuals. Limited studies describe genetic variation in coagulopathies, although faster and cheaper sequencing tools have changed our understanding of this topic. There are many genetic causes of both excess bleeding (eg, hemophilia) and excess clotting. Although African Americans have been shown to have an increased risk of thrombosis as compared to Caucasians, most of the inherited mechanisms of thrombosis that have been studied are present primarily in Caucasian populations, such as FV Leiden, resulting in resistance to protein C, and prothrombin G20210A.8,40,41 In general, strong evidence supports a tendency toward a prothrombotic phenotype in African Americans. Although the mechanism is not yet fully understood, this evidence includes a combination of differences in measured coagulation biomarkers as well as observations in increased thrombotic events.42

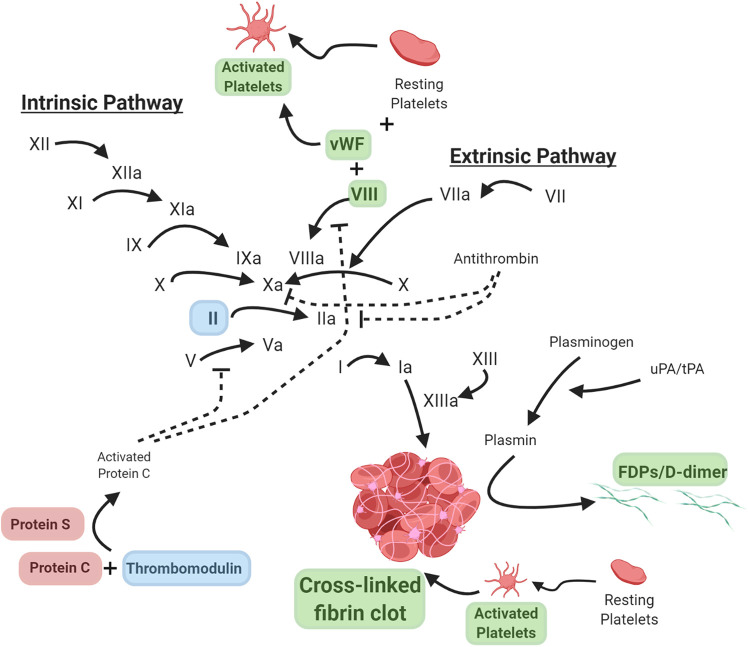

African Americans exhibit a well-documented trend toward having higher baseline levels of coagulation FVIII, increased levels of vWF, increased thrombin generation, and elevated baseline levels of D-dimer (Figure 1).43–48 Factor VIII plays a role in the intrinsic coagulation pathway and is frequently elevated in patients with severe systemic inflammation, as it is a positive acute-phase protein. An increase in FVIII can create an exaggerated coagulation response upon activation of the cascade and has been suggested to be related to resistance to heparin in critically ill patients.49,50 An increase in FVIII has been observed in patients with severe COVID-19.4 Another biomarker D-dimer is released upon the breakdown of a cross-linked fibrin clot, resultant from endogenous activation of the fibrinolytic pathway. Increase in D-dimer is typically used as a marker of active thrombosis and fibrinolysis, such as for the exclusion of a PE, DVT, or stroke, in conjunction with other clinical tests, such as imaging.51 African American women, in particular, have a higher incidence of thrombosis along with a higher level of D-dimer.46,52 D-dimer has also been reported to be an important biomarker of serious COVID-19 and has been shown to correlate with poor prognosis.1–4 African Americans have at least a 30% higher prevalence of venous thromboembolism (VTE), which is suspected to be at least in part due to variations in thrombomodulin, although there is conflicting evidence on the specific mechanism.53,54 Thrombomodulin modulates thrombin and increases the activation of protein C. Limited studies have also identified decreased levels of circulating protein C and protein S, endogenous anticoagulants, in African Americans.55–57 However, some genetic studies identify potential single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that may affect the level of circulating protein C in multiple groups, including increased levels of protein C in African Americans.58 While FV Leiden mutation, which results in activated protein C resistance, is a well-characterized mechanism of thrombosis in Caucasian populations, direct changes in protein C, protein S, and thrombomodulin have been found in some African Americans (as described above). African Americans also have increased levels of lipoprotein (a), which is known to play a role in the development of atherosclerosis and the predisposition to thrombosis due to its similarity to plasminogen, as well as through platelet activation.59,60 These findings support the need for further research in this area to fully understand the variations in baseline coagulation status, as they relate to the development of coagulopathies.

Figure 1.

Reported coagulation pathway variations in African Americans. Schematic of the coagulation pathway with specific variations in the African American population. Green indicates increased levels, red indicates decreased levels, and blue indicates possible genetic variants. * Note: This is not an exhaustive list of all factors that may affect coagulation in this population, such as sickle cell disease or systemic lupus erythematosus.

Another potential cause of increased thrombotic events in African American patients is sickle cell disease (SCD). Sickle cell disease is an inherited blood disorder, caused by a mutation in the HBB gene, that results in production of abnormal hemoglobin and can be identified by the traditional C-shaped (sickle-shaped) red blood cells in place of the traditional round cell shape.61,62 This morphologic change results in the cells having a higher likelihood of getting lodged in the microvasculature and more prone to aggregate than regular blood cells, causing blood flow obstruction and serving as a nidus for clot formation.63 These morphological red blood cell changes along with activation of the coagulation system may result in a vaso-occlusive crisis.64 Individuals with SCD are at a significantly higher risk of developing DVT and PE.61,62 In addition to increasing the rate of thrombus formation, the presence of the sickle shape also appears to result in a denser thrombus and the clot itself appears to be more resistant to fibrinolysis.65 Although clinical SCD is only present in an estimated 100 000 patients in the United States, the sickle cell trait is present in up to 8% of the African American population, with SCD flagged as an important risk factor for VTE.42

A small number of studies have explored genetic variations in the context of coagulation and the response to anticoagulation therapy. Some of these studies have suggested that African Americans may require higher doses of warfarin to stay within the target prothrombin time/international normalized ratio therapeutic window.66,67 One study examined the VKORC1 and CYP2C9 genes in the context of the African American population and the variability in patient response to warfarin treatment.68,69 That study identified that a SNP in the CYP2C cluster on chromosome 10 appeared to be associated with a clinically relevant effect on warfarin dose. Other studies examining higher rates of D-dimer elevations in African Americans have identified a potential genetic variation of the F3 loci, believed to be associated with this elevation.24 Studies evaluating metabolism of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have also identified potential differences in sulfation of active apixaban due to SULT1A1*3, an allelic variant of SULTA1 (a polymorphic variant of a sulfotransferase or SULT), which may be associated with a moderate potential to affect the anticoagulation effects of apixaban.70 Genome studies also describe genetic variants in vWF specific to African American women, although the resulting phenotype of these changes is not clear.71,72 Not all genotyping studies have demonstrated an increased risk factor in African Americans; for example, a mutation in FII (prothrombin), called prothrombin G20210A, is found in 1 in 250 African Americans, but is more common and represents a risk factor for Caucasians.73

Genetic and phenotypic variations in accessories to the coagulation pathway, such as in platelets, among racial and ethnic minority groups have also been suggested. Platelets play a major role in thrombosis and are a primary target, along with the coagulation pathway, in therapeutic regimens for the treatment of heart disease and other conditions associated with pathologic thrombosis. Multiple studies have shown that African American women tend to have a higher platelet count than Caucasians and Latinos (no difference was seen between men of all races).74–76 Novel gene mutations linked to changes in platelet counts, primarily increased platelet counts (thrombocytosis), in African Americans have been observed. Additionally, potential differences in platelet sensitivity to some traditional platelet inhibitor drugs have been demonstrated with varying results. In particular, there are multiple studies showing differences in the protease-activated receptor-4 pathway, with African Americans being less responsive to cyclooxygenase and P2Y12 receptor dual inhibition.76,77 These findings suggest that African Americans may not respond to platelet inhibitors similar to other races, and this may alter therapeutic efficacy in this population.

Furthermore, several conditions indirectly affect coagulation status. One major example is systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), an autoimmune disease that involves the body raising antibodies against receptors on cell membrane components, such as phospholipids, which increase systemic inflammation and may heighten a patient’s predisposition to thrombosis.42 While typical symptoms of SLE include systemic inflammation, swelling, and damage to the joints, kidneys, heart, and lungs, blood clotting is common as well. Systemic lupus erythematosus is 3 times more common in African American women than in Caucasian women, and up to 1 in every 250 African American women will develop SLE.78,79 Furthermore, its symptoms tend to be more severe in African Americans than in other races.79,80 Lupus anticoagulants, anticardiolipin antibodies, and β-2-glycoprotein I antibodies are antiphospholipid antibodies that are common in patients with SLE (as well as certain other patients). It is common for women, especially African American women, to develop antiphospholipid antibodies during pregnancy, a major cause of miscarriage in African American women.80,81 Interestingly, a few papers have demonstrated that there appears to be an increased frequency of lupus autoantibodies in patients with COVID-19, although the frequency of lupus anticoagulant is currently debated.82,83

One of the more common conditions that is a strong predisposing factor for VTE is chronic kidney disease (CKD).42,84 The development of mild-moderate CKD is associated with a 1.3- to 2-fold increased risk for VTE, while severe CKD is associated with up to a 2.3-fold increased risk compared to the general population. The predisposition to VTE formation in the face of CKD is due to many additive changes in coagulation that occur during renal impairment, including (1) elevated levels of D-dimer, C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, FVII, FVIII, and vWF (likely due to increased synthesis); (2) lower levels of FIX, FXI, and FXII (likely due to increased urinary loss); (3) decrease in endogenous anticoagulants, including AT (likely due to increased urinary loss); (4) increase in platelet activation and aggregation; and (5) decreased fibrinolytic activity.84 African Americans have an increased rate of CKD and end-stage renal disease, with an odds ratio of 3.89, compared to 1 in Caucasians, 2.74 in Native Americans, 1.56 in Asians, and 1.45 in Hispanics.85,86

In addition to the various factors listed above that may predispose African Americans to thrombosis (although this list is by no means exhaustive), prevalence of other conditions, such as an increased rate of heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes, also increases the risk of thrombosis. Some African Americans may be genetically predisposed to a baseline prothrombotic state; adding on other conditions, such as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, and other comorbidities, compounds the overall risk of coagulopathies.87,88 Among the population of African Americans who are infected with COVID-19, some of these patients may already reside in a prothrombotic state prior to COVID-19 because of higher baseline concentrations of FVIII, vWF, and D-dimer, as well as increased platelet activation. This may potentially account for some of the increase in disease severity observed in this population.

Socioeconomic Factors Affecting Coagulation Management

In addition to the physiologic mechanisms that may predispose African Americans to a prothrombotic state, other key factors, such as socioeconomic status, may adversely affect coagulation management for this prothrombotic phenotype. Although some common comorbid conditions may be inherited, access to medical care, medication, healthy food, and lifestyle habits play a key role in treatment and control of the disease.89–91

Patterns of increased COVID-19 prevalence, morbidity, and mortality are concentrated in areas with lower socioeconomic status, coinciding with underserved racial and ethnic communities.36,37 These populations may have greater numbers of residents per household, be economically unable to miss work (even if sick) and are more likely to have multigenerational family members residing in one abode; these factors often make practicing social isolation difficult. This risk is further exacerbated by difficulties with travel or the ability to afford chronic care and long-term medications, creating a perfect storm for an infection such as COVID-19.36,37,92

Disparities extend to treatment as well. Studies have shown that African Americans tend not to be managed with the same treatments as those commonly prescribed to other racial and ethnic groups. For example, some studies have noted that although African Americans tend to exhibit higher rates of atrial fibrillation and thrombosis, they are less likely to be prescribed anticoagulants compared to their Caucasian counterparts.93,94 Even when prescribed, African American patients tend to spend less time within the therapeutic range for warfarin treatment.66 Similarly, prescription of DOACs in the African American community has been limited compared to other racial and ethnic groups, despite the significant increase in DOAC use in the United States (now surpassing warfarin). Interestingly, some studies have shown that these differences in anticoagulation trends are present even when controlling for socioeconomic variables.66, 94–96 Additionally, despite the evidence suggesting that genetic variations may alter the response to various anticoagulants and platelet inhibitors, as discussed in this article, African Americans comprise fewer than 4% of the clinical trial population for many of these anticoagulants.97 Due to the low representation of African Americans in these clinical trial populations, it is possible that any natural variation in clinical response would not be observed as the trial is likely not powered for this purpose. Thus, the administration of standard anticoagulation therapy, as based on data sourced from Caucasian patients, may be subtherapeutic in African American patients, potentially resulting in inadequate anticoagulation.

Conclusions

In this report, we consider the contribution of both “nature” and “nurture” to the increased rate of COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality among African Americans. COVID-19 produces severe inflammation and a prothrombotic state that culminates in thrombotic events. African Americans are more likely than other racial and ethnic groups to be in a prothrombotic state or to be primed for a prothrombotic state. Coupled with the higher rate of preexisting conditions that predispose patients to higher rates of COVID-19 and disease, and the lower rate of therapeutic anticoagulation even when warranted, variation in coagulation status may be one of the factors that puts African Americans at higher risk. Given the potential differences in response to anticoagulant therapy, it remains unclear whether standard dosing effectively achieves the appropriate level of anticoagulation among hospitalized COVID-19-positive African Americans. Although this work focuses on trends in African Americans, further examination of COVID-19 trends may demonstrate the urgent need for both personalized medicine and population-based care, particularly with respect to anticoagulation management.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Piazza has received research grant support from EKOS, a BTG International Group company, Bayer, the Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, Daiichi-Sankyo, Portola, and Janssen and consulting fees from Amgen, Pfizer, Boston Scientific Corporation, and Thrombolex. In addition to her academic appointments, Dr Frydman is the Chief Science Officer of Coagulo Medical Technologies, Inc.

ORCID iD: Galit H. Frydman  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8126-8580

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8126-8580

References

- 1. Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, et al. Anticoagulation treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094–1099. doi:10.1111/jth.14817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1023–1026. doi:10.1111/jth.14810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Panigada M, Bottino N, Tagliabue P, et al. Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit. A report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. doi:10.1111/jth.14850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al. COVID19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033 doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Foley JH, Conway EM. Cross talk pathways between coagulation and inflammation. Circ Res. 2016;118(9):1392–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1891–1892. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zakai NA, McClure LA. Racial differences in venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(10):1877–1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoffman M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280. e8 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gurwitz D. Angiotensin receptor blockers as tentative SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics [published online March 04, 2020]. Drug Dev Res. 2020:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xu H, Zhong L, Deng J, et al. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bertram S, Heurich A, Lavender H, et al. Influenza and SARS-coronavirus activating proteases TMPRSS2 and HAT are expressed at multiple sites in human respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhen YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(5):259–260. doi:10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leung JM, Yang CX, Tam A, et al. ACE-2 expression in the small airway epithelia of smokers and COPD patients: implications for COVID-19. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5):2000688 doi:10.1183/13993003.00688-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao Q, Meng M, Kumar R, et al. The impact of COPD and smoking history on the severity of Covid-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020. doi:10.1002/jmv.25889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McGonagle D, O’Donnell JS, Sharif K, Emery P, Bridgewood C. Immune mechanisms of pulmonary intravascular coagulopathy in COVID-19 pneumonia. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2(7):E437–E445. doi:10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30121-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pechlivani N, Ajjan RA. Thrombosis and vascular inflammation in diabetes: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018;5:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Akassoglou K. Coagulation takes center stage in inflammation. Blood. 2015;125(3):419–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu Y. Contact pathway of coagulation and inflammation. Thromb J. 2015;13:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vilahur G, Ben-Aicha S, Badimon L. New insights into the role of adipose tissue in thrombosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113(9):1046–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Panova-Noeva M, Chulz A, Arnold N, et al. Coagulation and inflammation in long-term cancer survivors: results from the adult population. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16(4):699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Razak NBA, Jones G, Bhandari M, Berndt MC, Metharom P. Cancer-associated thrombosis: an overview of mechanisms, risk factors, and treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10(10):380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fox SE, Akmatbekov A, Harbert JL, et al. Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in African American patients with COVID-19: an autopsy series from New Orleans [published online May 27, 2020]. Lancet Respir Med. 2020. doi:10.1016.S2213-2600(20)30243-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Baergen RN, Heller DS. Placental pathology in COVID-19 positive mothers: preliminary findings. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2020;23(3):177–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shanes ED, Mithal LB, Otero S, et al. Placental pathology in COVID-19. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;154(1):23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nahum J, Morichau-Beauchant T, Daviaud F, et al. Venous thrombosis among critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e2010478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leonard-Lorant I, Delabranche X, Severac F, et al. Acute pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients on CT angiography and relationship to d-dimer levels. Radiology. 2020;201561 doi:10.1148/radiol.2020201561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Poissy J, Goutay J, Caplan M, et al. Pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: awareness of an increased prevalence. Circulation. 2020. doi:10.116/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Al-Ani F, Chedhade S, Lazo-Langber A. Thrombosis risk associated with COVID-19 infection. A scoping review. Thromb Res. 2020;192:152–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Middeldorp S, Coppems M, van Haaps T, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. doi:10.111/jth.14888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ignat M, Philouza G, Aussenac-Belle L, et al. Small bowel ischemia and SARS-CoV-2 infection: an underdiagnosed distinct clinical entity. Surgery. 2020;168(1):14–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kaafarani HMA, El Moheb M, Hwabejire JO, et al. Gastrointestinal complications in critically ill patients with COVID-19 [published online May 01, 2020]. Ann Surg. 2020. https://journals.lww.com/annalsofsurgery/Documents/Gastrointestinal%20Complications%20in%20Critically%20Ill%20Patients%20with%20COVID-19.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine: coronavirus resource center. 2020. Accessed May 2020 https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data#charts.

- 37. Thebault R, Ba Tran A, Williams V. The coronavirus is infecting and killing black Americans at an alarmingly high rate. Washington Post. April 7, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/04/07/coronavirus-is-infecting-killing-black-americans-an-alarmingly-high-rate-post-analysis-shows/?arc404=true

- 38. McGonagle D, Plein S, O’Donnell JS, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality in African Americans with COVID-19 [published online May 27, 2020]. Lancet Respir Med. 2020. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30244-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Palmer VS. Rapid response: African Americans: biological factors and elevated risk for COVID-19. BMJ. 2020;369:m1873.32393504 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ornstein DL, Cushman DL. Factor V Leiden. Circulation. 2003;107(15):e94–e97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ridker PM, Miletich JP, Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Ethnic distribution of Factor V Leiden in 4047 men and women. JAMA. 1997;277(16):1305–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Buckner TW, Key NS. Venous thromboembolism in blacks. Circulation. 2012;125(6):837–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Miller CH, Dilley A, Richardson DA, Hooper WC, Evatt BL. Population differences in von Willebrand factor levels affect the diagnosis of von Willebrand disease in African-American women. Am J Hematol. 2001;67(2):125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Roberts LN, Patel RK, Chitongo P, Bonner L, Arya R. African-Caribbean ethnicity is associated with a hypercoagulable state as measured by thrombin generation. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24(1):40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Janbain M, Liszewski WJ, Leissinger CA. Analysis of racial disparity in plasma of healthy volunteers using rotational thromboelastography reveals higher prothrombotic profile in African Americans. Blood. 2014;124(21):5972. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Raffield LM, Zakai NA, Duan Q, et al. d-Dimer in African Americans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:2220–2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kyrle PA, Hirschl MM, Milena Stain CB, et al. High plasma levels of Factor VIII and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(7):457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Patel RJ, Ford E, Thumpston J, Arya R. Risk factors for venous thrombosis in the black population. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90(5):835–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Faustino EV, Li S, Silva CT, et al. Factor VIII may predict catheter-related thrombosis in critically ill children: a preliminary study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16(6):497–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kamphuisen PW, Eikenboom JCJ, Bertina RM. Elevated Factor VIII levels and the risk of thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21(5):731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Value of d-dimer testing on the exclusion of pulmonary embolism in patients with previous venous thromboembolism. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(2):176–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Khaleghi M, Saleem U, McBane RD, Mosley TH, Jr, Kullo IJ. African American ethnicity is associated with higher plasma levels of d-dimer in adults with hypertension. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(1):34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hernandez W, Gamazon ER, Smithberger E, et al. Novel genetic predictors of venous thromboembolism risk in African Americans. Blood. 2016;127(15):1923–1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Folsom AR, Roetker NS, Kelley ST, Tang W, Pankratz N. Failure to replicate genetic variant predictors of venous thromboembolism in African Americans. Blood. 2017;130(5):688–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jerrard-Dunne P, Evans A, McGovern R, et al. Ethnic differences in markers of thrombophilia, implications for the investigation of ischemic stroke in multiethnic populations: the south London ethnicity and stroke study. Stroke. 2003;34(8):1821–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fall AOT, Proulle V, Sall A, et al. Risk factors for thrombosis in an African population. Clin Med Insights Blood Disord. 2014;7:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Daneshjou R, Cavalleri LH, Weeke PE, et al. Population-specific single-nucleotide polymorphism confers increased risk of venous thromboembolism in African Americans. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2016;4(5):513–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Munir MS, Weng LC, Tang W, et al. Genetic markers associated with plasma protein C level in African Americans: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Genet Epidemiol. 2014;38(8):709–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Folsom AR, Chamberlain A. Lipoprotein(a) and venous thromboembolism. Am J Med. 2008;121(2):e17–e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rotimi CN, Cooper RS, Marcovina SM, et al. Serum distribution of lipoprotein(a) in African Americans and Nigerians: potential evidence for a genotype-environmental effect. Genet Epidemiol. 1997;14(2):157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Naik RP, Streiff MB, Haywood C, Jr, Nelson JA, Lanzkron S. Venous thromboembolism in adults with sickle cell disease: a serious and under-recognized complication. Am J Med. 2013;126(5):443–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Noubiap JJ, Temgoua MN, Tankeu R, et al. Sickle cell disease, sickle trait and the risk for venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb J. 2018;16:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Faes C, Ilich A, Sotiaux A, et al. Red blood cells modulate structure and dynamics of venous clot formation in sickle cell disease. Blood. 2019;133(23):2529–2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Manwani D, Frenette PS. Vaso-occlusion in sickle cell disease: pathophysiology and novel target therapies. Blood. 2013;122(24):3892–3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sparkeborough EM, Chen C, Brzoska T, et al. Thrombin activation of PAR-1 contributes to microvascular stasis in mouse models of sickle cell disease. Blood. 2020;135(20):1783–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Akinboboye O. Use of oral anticoagulants in African-American and Caucasian patients with atrial fibrillation: is there treatment disparity? J Multidiscip Healthc. 2015;8:217–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Limdi NA, Brown TM, Yan Q, et al. Race influences warfarin dose changes associated with genetic factors. Blood. 2015;126(4):539–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Fung E, Patsopoulos NA, Belknap SM, et al. Effect of genetic variants, especially CYP2C9 and VKORC1, on the pharmacology of warfarin. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2012;38(8):893–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Dean L. Warfarin therapy and VKORC1 and CYP genotype In: Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kanuri SH, Kreutz RP. Pharmacogenomics of novel direct oral anticoagulants: newly identified genes and genetic variants. J Pers Med. 2019;9(1):7 doi:10.3390/jpm9010007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhou Z, Yu F, Buchanan A, et al. Possible race and gender divergence in association of genetic variations with plasma von Willebrand factor: a study of ARIC and 1000 genome cohorts. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e84810 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Flood VH, Gill JC, Morateck PA, et al. Common VWF exon 28 polymorphisms in African Americans affecting the VWF activity assay by ristocetin factor. Blood. 2010;116(2):280–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Prothrombin G20210A (factor II mutation) resources: a genetic clotting condition or thrombophilia. Accessed May 2020 https://www.stoptheclot.org/learn_more/prothrombin-g20210a-factor-ii-mutation/#:∼:text=A%20Genetic%20Clotting%20Condition%20or,protein%20that%20helps%20blood%20clot.

- 74. Saxena S, Cramer AD, Weiner JM, Carmel R. Platelet counts in three racial groups. Am J Clin Pathol. 1987;88(1):106–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Qayyum R, Snively BM, Ziv E, et al. A meta-analysis and genome-wide association study of platelet count and mean platelet volume in African Americans. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(3):e1002491 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Edelstein LC, Simon LM, Montoya RT, et al. Racial difference in human platelet PAR4 reactivity reflects expression of PCTP and miR-376c. Nat Med. 2013;19(12):1609–1616. doi:10.1038/nm.3385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Edelstein LC, Simon LM, Lindsay CR, et al. Common variants in the human platelet PAR4 thrombin receptor alter platelet function and differ by race. Blood. 2014;124(23):3450–3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Byron MA. The clotting defect in SLE. Clin Rheum Dis. 1982;8(1):137–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sibanda EN, Chase-Topping M, Pfavayi LT, Woolhouse MEJ, Mutapi F. Evidence of a distinct group of Black African patients with systemic lupus erythrmatosus. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(5):e000697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Office of Women’s Health, CDC. Lupus in women. 2018. Accessed May 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/lupus/basics/women.htm.

- 81. Myers B, Pavord S. Review: diagnosis and management of antiphospholipid syndrome in pregnancy. Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;13(1):15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Harzallah I, Debliquis A, Drenou B. Lupus anticoagulant is frequent in patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020. doi:10.111/jth.14867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Gartshteyn Y, Askanase AD, Schmidt NM, et al. COVID-19 and systemic lupus erythematosus: a case series. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020. doi:10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30161-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Wattanakit K, Cushman M. Chronic kidney disease and venous thromboembolism: epidemiology and mechanisms. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2009;15(5):408–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Norris KC, Agodoa LY. Unraveling the racial disparities associated with kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68(3):914–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. United States Renal Data System. 2017. USRDS Annual Data Report: Executive Summary. Volume 1—CKD in the United States. 2017 Accessed May 2020 https://www.usrds.org/2017/download/2017_Volume_1_CKD_in_the_US.pdf.

- 87. Cavallari I, Morrow DA, Creager MA, et al. Frequency, predictors, and impact of combined antiplatelet therapy on venous thromboembolism in patients with symptomatic atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2018;137(7):684–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Putcha N, Han M, Martinez CH, et al. Comorbidities of COPD have a major impact on clinical outcomes, particularly in African Americans. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2014;1(1):105–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Isma N, Merlo J, Ohlsson H, et al. Socioeconomic factors and concomitant diseases are related to the risk for venous thromboembolism during long time follow-up. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013;36(1):58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Kort D, van de Meer FJM, Vermass HW, et al. Relationship between neighborhood socioeconomic status and venous thromboembolism: results from a population-based study. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15(12):2352–2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zoller B, Li Z, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Socioeconomic and occupational risk factors for venous thromboembolism in Sweden: a nationwide epidemiological study. Thromb Res. 2012;129(5):577–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Centers for Disease Control. Health Disparities experienced by black or African Americans—United States. MMWR. 2005;54(01):1–3. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5401a1.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Magnani JW, Norby FL, Agarwal SK, et al. Racial differences in atrial fibrillation-related cardiovascular disease and mortality: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(4):433–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Essien UR, Holmes DN, Jackson LR II, et al. Association of race/ethnicity with oral anticoagulant use in patients with atrial fibrillation: findings from the outcomes registry for better informed treatment of atrial fibrillation II. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(12):1174–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Nathan AS, Geng Z, Dayoub EJ, et al. Racial, ethnic and socioeconomic inequities in the prescription of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with venous thromboembolism in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(4):e005600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Schaefer JK, Sood SL, Haymart B, et al. A comparison of socioeconomic factors in patients continuing warfarin versus those transitioning to direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for venous thromboembolism disease or atrial fibrillation. Blood. 2016;128(22):1179. [Google Scholar]

- 97. Food and Drug Administration. Accessdata.fda.gov. Clinical trial data for ARISTOTLE, AMPLIFY, AMPLIFY-EXT, ROCKET AF, EINSTEIN and EINSTEIN CHOICE Clinical trials.