Abstract

Objectives

The risk of mother-to-child HIV transmission can be reduced to ≤0.5% if the mother’s HIV status is known before delivery. This study describes 2006-2014 trends in diagnosed HIV infection documented on delivery discharge records and associated sociodemographic characteristics among women who gave birth in US hospitals.

Methods

We analyzed data from the 2006-2014 National Inpatient Sample and identified delivery discharges and women with diagnosed HIV infection by using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes. We used a generalized linear model with log link and binomial distribution to assess trends and the association of sociodemographic characteristics with an HIV diagnosis on delivery discharge records.

Results

During 2006-2014, an HIV diagnosis was documented on approximately 3900-4400 delivery discharge records annually. The probability of having an HIV diagnosis on delivery discharge records decreased 3% per year (adjusted relative risk [aRR] = 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99), with significant declines identified among white women aged 25-34 (aRR = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.88-0.97) or those using Medicaid (aRR = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.90-0.97); among black women aged 25-34 (aRR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.92-0.99); and among privately insured women who were black (aRR = 0.96; 95% CI, 0.92-0.99), Hispanic (aRR = 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86-0.98), or aged 25-34 (aRR = 0.96; 95% CI, 0.92-0.99). The probability of having an HIV diagnosis on delivery discharge records was greater for women who were black (aRR = 8.45; 95% CI, 7.56-9.44) or Hispanic (aRR = 1.56; 95% CI, 1.33-1.83) than white; for women aged 25-34 (aRR = 2.33; 95% CI, 2.12-2.55) or aged ≥35 (aRR = 3.04; 95% CI, 2.79-3.31) than for women aged 13-24; and for Medicaid recipients (aRR = 2.70; 95% CI, 2.45-2.98) or the uninsured (aRR = 1.87; 95% CI, 1.60-2.19) than for privately insured patients.

Conclusion

During 2006-2014, the probability of having an HIV diagnosis declined among select sociodemographic groups of women delivering neonates. High-impact prevention efforts tailored to women remaining at higher risk for HIV infection can reduce the risk of mother-to-child HIV transmission.

Keywords: HIV, delivery, perinatal, mother-to-child transmission, national estimates

Screening for HIV is an essential step to prevent mother-to-child (perinatal) transmission. When the HIV status of a mother is known before delivery, the risk of perinatal HIV transmission can be reduced from 25% to ≤0.5%1 by appropriate antiretroviral treatment of the mother,2 elective cesarean section,3,4 avoidance of breastfeeding,5 and administration of appropriate antiretroviral prophylaxis to an exposed newborn within hours after birth.2 Successful reduction and, eventually, elimination of mother-to-child HIV transmission require coordinated efforts involving women with HIV infection, health care providers, case managers, social workers, and public health professionals.6,7 National estimates of women with HIV infection, diagnosed before or at delivery, and of their demographic and health insurance characteristics will help allocate appropriate resources,8 inform guidance for policies on HIV testing, and monitor progress toward elimination of perinatal transmission.9

National trends in deliveries to women with HIV infection in the United States are not well described. Whitmore et al8 used an indirect method and HIV surveillance data for 2006 from states with confidential name-based case reporting and estimated that 8700 infants were born to women with HIV infection nationwide. Ewing et al10 used hospital discharge data for 2007 and 2011 and estimated that 5397 women in 2007 and 3855 women in 2011 with an HIV diagnosis gave birth in US hospitals. The objective of our study was to describe trends in the annual number and rate of deliveries to women with an HIV diagnosis that occurred in US hospitals during 2006-2014 by using a nationally representative sample of hospitalizations and a comprehensive list of HIV diagnosis codes.

Methods

Data

We analyzed data from the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality11 for 2006-2014. In October 2015, the United States transitioned inpatient diagnosis coding from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) to the ICD-10-CM, which substantially shifted trends in hospital stays with certain medical conditions.12 Because analyzing the effects of the transition in codes was beyond the scope of our analysis, we excluded data from 2015-2016 and focused on years that consistently used ICD-9-CM codes (ie, 2006-2014).

NIS represents more than 96% of all hospital discharges in the United States. Each year, NIS collects data on 7-8 million discharges, which, when weighted, represent 35-39 million discharges. These large numbers of discharges allow for analyses of rare conditions and special patient populations. For each hospital stay, NIS included up to 15 diagnoses during 2006-2008, up to 25 diagnoses during 2009-2013, and up to 30 diagnoses in 2014. NIS also included data on the primary expected health insurer and patient demographic characteristics.

In 2012, NIS changed its sampling strategy from selecting a random sample of 20% of US hospitals to sampling 20% of discharges across all US hospitals.11 In addition, NIS switched from weights based on hospital admissions to weights based on discharges. The new sampling and weighting strategies reduced the width of confidence intervals (CIs) by half and resulted in a one-time drop in discharge counts by about 4%.11 To make the discharge counts comparable across all years, we used the revised 2006-2011 NIS trend weights.13 Because NIS is a publicly available database that eliminates all patient identifiers, this study did not require institutional review board approval.

Identification of Delivery Hospitalizations and HIV Diagnoses

Following methods described in previous studies,14,15 we identified delivery discharges by using ICD-9-CM16 and diagnosis-related group (DRG)17 codes. Starting with 2007 data, NIS reported codes from DRG version 24 (DRG24), which could handle a maximum of 579 diagnoses, and Medicare Severity DRGs (MS-DRGs), which increased the number of DRGs by 207 (in effect since October 1, 2007).18,19 Consequently, we used DRG24 to determine delivery discharges during 2006-2007 and MS-DRG to determine delivery discharges during 2008-2014 (Table 1). Alternatively, we identified a delivery discharge by the presence of discharge records with a set of ICD-9-CM codes.

Table 1.

Definitions of delivery discharges, HIV diagnoses, and dependent and independent variables for study on trends in deliveries among women with an HIV diagnosis in the United States, 2006-2014a

| Item | Definition |

|---|---|

| Delivery discharge | DRG codes14,15

ICD-9-CM codes14,15

|

| HIV diagnosis | CCS diagnosis code 5 that includes the following ICD-9-CM codes20

|

| Dependent variable | The presence of discharge records with HIV ICD-9-CM codes at delivery |

| Independent variables | |

| Year | Time trend (years) |

| Race/ethnicity | Race/ethnicity identifier categorized as white, black, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, other, or missing/invalid. In HCUP NIS, ethnicity takes precedence over race; therefore, white and black patients represent the non-Hispanic population.19 |

| Age at delivery | Patient’s age in years19 categorized as 13-24, 25-34, and ≥35 |

| Expected primary health insurer | Primary expected payer identifier19 categorized as private health insurance (Blue Cross/Blue Shield, other commercial carriers, private health maintenance, and preferred provider organizations), Medicaid, Medicare, and other government insurance (eg, worker’s compensation, CHAMPUS, CHAMPVA) combined with uninsured (“self-pay” and “no charge”)c |

| Median annual household income | Median annual household income for patient’s zip code; varied by year19

|

| Census region of hospital | Information was obtained from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey of Hospitals19; categorized as Northeast, Midwest, South, or West |

Abbreviations: CCS, Clinical Classifications Software; CHAMPUS, Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services; CHAMPVA, Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs; DRG, diagnosis-related group; DRG24, DRG version 24; HCUP, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; MS-DRG, Medicare Severity DRG; NIS, National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample.

aData source: National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for 2006-2014.11

bICD-9-CM code for HIV-2 infection (079.53) used as an additional diagnosis to indicate cases of illness resulting from infection with HIV-2.21 All other HIV-related ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes are assumed to be for HIV-1.21

cBecause the unweighted number of delivery discharges with an HIV diagnosis in the category of government insurance did not exceed 10 discharges per year, we combined data for the categories of government insurance and uninsured.

To identify HIV diagnoses, we used Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Clinical Classifications Software,20 which defines HIV by the presence of discharge records with any of the ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes listed in Table 1. An HIV diagnosis could have been made at any point in the past or based on tests obtained during a hospitalization.

Statistical Analyses

To account for the multilevel sampling design of NIS data, stratified on hospital characteristics, we used Stata version 14.022 command “svyset hosp_nis [pw = discwt], strata(nis_stratum)” to ensure that variance calculations accounted for the clustering of discharges within hospitals23 when (1) estimating the annual weighted number of delivery hospitalizations and the annual weighted number of delivery discharges with an HIV diagnosis per 10 000 deliveries and (2) examining the association of patients’ sociodemographic characteristics with an HIV diagnosis on discharge records.

We used Stata command “mean2” to examine which sociodemographic characteristics of delivery discharges with and without an HIV diagnosis significantly changed from 2006 to 2014. To determine whether there was an increasing or decreasing trend in the probability of having an HIV diagnosis on discharge records during 2006-2014, we estimated crude relative risks (RRs) and 95% CIs by using a generalized linear model with log link and binomial distribution, where the dependent variable indicated the presence of delivery discharge records with ICD-9-CM codes indicating HIV. To examine the impact of potentially confounding effects, we then estimated the adjusted relative risk (aRR) for the temporal trend, where the set of covariates included patients’ sociodemographic characteristics listed and defined in Table 1. To account for interactions that represent differential trends in race/ethnicity and expected primary health insurer groups, we stratified the analyses within each category of race/ethnicity and expected primary health insurer group by the remaining sociodemographic characteristics. For each stratified analysis, we estimated crude RRs and aRRs for the temporal trend in HIV diagnoses.

Results

Delivery-Related Hospitalizations by HIV Type, Health Insurance Status, and Demographic Characteristics

During 2006-2014, the distribution of ICD-9-CM codes and types of HIV diagnoses were stable (Table 2). Of the delivery discharges with an HIV diagnosis, most (72.5%-79.6%) had a diagnosis of asymptomatic HIV type 1 infection, and fewer than one-quarter (18.5%-24.9%) of discharges had a diagnosis of HIV type 1 disease. Few delivery discharges had a diagnosis of HIV type 2 (HIV-2) (0.1%-0.6%). A preliminary test for HIV was positive for 1.2% to 2.6% of women, but their HIV infection status was not yet confirmed at the time of hospital discharge.

Table 2.

HIV diagnosis on discharge records at delivery, by HIV type and year, United States, 2006-2014a

| HIV Diagnoses at Delivery | 2006 (N = 4377), % | 2007 (N = 5209), % | 2008 (N = 3960), % | 2009 (N = 4761), % | 2010 (N = 4587), % | 2011 (N = 3758), % | 2012 (N = 3750), % | 2013 (N = 3850), % | 2014 (N = 3915), % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV disease type 1 (HIV-1) (ICD-9-CM code 042.x) | 20.2 | 20.2 | 23.1 | 22.9 | 24.9 | 18.6 | 18.8 | 18.5 | 18.7 |

| HIV-1 infection (ICD-9-CM code V08.x) | 77.1 | 78.0 | 74.2 | 75.1 | 72.5 | 79.4 | 78.9 | 79.4 | 79.6 |

| HIV infection type 2 (HIV-2) (ICD-9-CM code 079.53) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Positive preliminary test for HIV (ICD-9-CM code 795.71) | 2.6 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.2 |

Abbreviations: ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; N, number of delivery hospitalizations.

aData source: The National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for 2006-2014.11 All results in this table (ie, number of discharges and percentages) represent weighted samples.

The sociodemographic characteristics of women with and without an HIV diagnosis on their discharge records were mostly stable during 2006-2014 (Table 3). The percentage of patients aged ≥25 was consistently higher among women with an HIV diagnosis than among women without an HIV diagnosis on their discharge record. Of delivery discharges with an HIV diagnosis, 68.1% in 2006 and 68.5% in 2014 occurred among Medicaid recipients and 20.2% in 2006 and 21.3% in 2014 occurred among privately insured women. Of delivery discharges without an HIV diagnosis, 50.2% in 2006 and 50.7% in 2014 occurred among privately insured women and 42.4% in 2006 and 42.9% in 2014 occurred among Medicaid recipients. Women with an HIV diagnosis consistently represented more socially disadvantaged populations: 41.0%-49.6% of delivery discharges with an HIV diagnosis and 26.8%-27.4% of delivery discharges without an HIV diagnosis were among women living in areas with the lowest median annual household income (first income quartile: ≤$37 999 in 2006, ≤$39 999 in 2014). In contrast, only 7.6%-9.2% of delivery discharges with an HIV diagnosis and 21.4%-22.2% of delivery discharges without an HIV diagnosis were among women living in areas with the highest median annual household income (fourth quartile: ≥$62 000 in 2006, ≥$66 000 in 2014).

Table 3.

Delivery discharges by HIV diagnostic status and relative risk of an HIV diagnosis at delivery, United States, 2006-2014a

| Characteristic | HIV Diagnosis | No HIV Diagnosis | Crude RR (95% CI) (N = 35 246 928) |

Adjustedd RR (95% CI) (N = 35 246 928) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006, % (N = 4377) | 2014, % (N = 3915) | % Change From 2006 to 2014b | P Valuec | 2006 (N = 4 135 547) | 2014 (N = 3 801 320) | % Change From 2006 to 2014b | P Valuec | |||

| Year | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.99 (0.96-1.02) | 0.97 (0.94-0.99) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 14.9 | 14.7 | −0.2 | .92 | 37.0 | 50.2 | 13.2 | <.001 | Reference | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic black | 43.1 | 62.3 | 19.2 | <.001 | 8.7 | 13.4 | 4.7 | <.001 | 13.76 (12.30-15.40) | 8.45 (7.56-9.44) |

| Hispanic | 14.4 | 10.7 | −3.7 | .26 | 20.2 | 19.4 | −0.8 | .67 | 2.03 (1.70-2.43) | 1.56 (1.33-1.83) |

| Other | 6.5 | 5.2 | −1.3 | .51 | 6.7 | 10.6 | 3.9 | <.001 | 1.92 (1.64-2.25) | 1.58 (1.34-1.87) |

| Missing/invalid data | 21.1 | 7.0 | −14.1 | .002 | 27.4 | 6.4 | −21.0 | <.001 | 2.20 (1.75-2.78) | 2.31 (1.84-2.89) |

| Age at delivery, y | ||||||||||

| 13-24 | 27.5 | 22.1 | −5.4 | .06 | 35.8 | 28.6 | −7.2 | <.001 | Reference | Reference |

| 25-34 | 55.7 | 59.4 | 3.7 | .29 | 50.0 | 55.8 | 5.8 | <.001 | 1.37 (1.25-1.51) | 2.33 (2.12-2.55) |

| ≥35 | 16.9 | 18.5 | 1.6 | .43 | 14.2 | 15.6 | 1.4 | .001 | 1.51 (1.38-1.65) | 3.04 (2.79-3.31) |

| Expected primary health insurer | ||||||||||

| Medicare | 4.1 | 5.1 | 1.0 | .30 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 | <.001 | 12.60 (10.59-14.99) | 6.47 (5.45-7.67) |

| Medicaid | 68.1 | 68.5 | 0.4 | .91 | 42.4 | 42.9 | 0.5 | .71 | 3.81 (3.42-4.25) | 2.70 (2.45-2.98) |

| Private | 20.2 | 21.3 | 1.1 | .70 | 50.2 | 50.7 | 0.5 | .79 | Reference | Reference |

| Self-pay, no charge, other | 7.5 | 5.1 | −2.4 | .26 | 6.9 | 5.7 | −1.3 | .08 | 2.79 (2.37-3.28) | 1.87 (1.60-2.19) |

| Median annual household income for patient’s zip code, $e | ||||||||||

| 1st quartile | 49.6 | 41.0 | −8.6 | .02 | 26.8 | 27.4 | 0.6 | .67 | 4.06 (3.17-5.20) | 1.90 (1.58-2.29) |

| 2nd quartile | 21.7 | 23.1 | 1.4 | .51 | 25.1 | 26.1 | 1.0 | .32 | 2.02 (1.63-2.51) | 1.45 (1.24-1.71) |

| 3rd quartile | 16.6 | 14.9 | −1.7 | .39 | 23.9 | 23.6 | −0.3 | .73 | 1.51 (1.25-1.81) | 1.28 (1.11-1.49) |

| 4th quartile | 7.6 | 9.2 | 1.6 | .45 | 22.2 | 21.4 | −0.8 | .62 | Reference | Reference |

| Missing/invalid data | 4.5 | 11.7 | 7.2 | .003 | 2.0 | 1.5 | −0.5 | .18 | 14.42 (10.80-19.27) | 6.63 (4.99-8.80) |

| Census region | ||||||||||

| Northeast | 25.0 | 22.0 | −3.0 | .42 | 15.2 | 16.0 | 0.8 | .43 | 6.06 (4.16-8.84) | 3.66 (2.55-5.26) |

| Midwest | 13.0 | 15.6 | 2.6 | .46 | 22.3 | 21.3 | −1.0 | .39 | 2.50 (1.66-3.77) | 2.07 (1.41-3.04) |

| South | 53.8 | 56.4 | 2.6 | .64 | 37.0 | 38.5 | 1.5 | .45 | 6.07 (4.08-9.01) | 3.62 (2.50-5.25) |

| West | 8.2 | 6.0 | −2.2 | .35 | 25.5 | 24.2 | −1.3 | .46 | Reference | Reference |

Abbreviations: —, not applicable; RR, relative risk.

aN is number of delivery discharges. All results (ie, number of delivery discharges, frequencies, and RRs) represent weighted samples. Data source: National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for 2006-2014.11

bPercentage-point change.

cSignificant if P < .05; estimated by using Stata command mean.2

dIn the adjusted model, the set of covariates included temporal trend and patients’ sociodemographic characteristics (race/ethnicity, age at delivery, expected primary health insurer, median annual household income for patient’s zip code, and census region).

eIncome quartiles in 2006: 1st quartile, $1-$37 999; 2nd quartile, $38 000-$46 999; 3rd quartile, $47 000-$61 999; 4th quartile, ≥$62 000. Income quartiles in 2014: 1st quartile, $1-$39 999; 2nd quartile, $40 000-$50 999; 3rd quartile, $51 000-$65 999; 4th quartile, ≥$66 000.

The probability of having an HIV diagnosis on discharge records at delivery varied by race/ethnicity, age, health insurance status, annual household income, and census region (Table 3). The probability of having an HIV diagnosis, compared with not having an HIV diagnosis, was higher for women who were black (aRR = 8.45; 95% CI, 7.56-9.44) or Hispanic (aRR = 1.56; 95% CI, 1.33-1.83) than for women who were white; for women aged 25-34 (aRR = 2.33; 95% CI, 2.12-2.55) or ≥35 (aRR = 3.04; 95% CI, 2.79-3.31) than for women aged 13-24; for Medicaid recipients (aRR = 2.70; 95% CI, 2.45-2.98) or the uninsured (aRR = 1.87; 95% CI, 1.60-2.19) than for privately insured patients; for women residing in areas in the first income quartile (aRR = 1.90; 95% CI, 1.58-2.29) than for women residing in areas in the fourth income quartile; and for discharges recorded in the Northeast (aRR = 3.66; 95% CI, 2.55-5.26) or the South (aRR = 3.62; 95% CI, 2.50-5.25) than in the West.

Estimated Number of Women With an HIV Diagnosis on Discharge Records

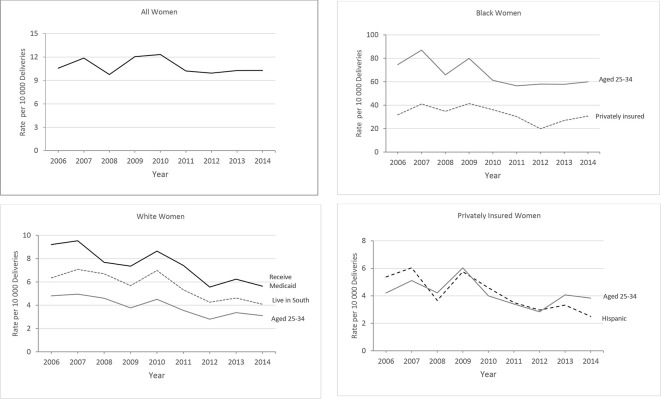

During 2006-2014, a total of 35.3 million delivery discharges (95% CI, 34.1-36.5 million) occurred in US hospitals, and 38 167 (95% CI, 33 523-42 809) had an HIV diagnosis on the record. Overall, the number of delivery hospitalizations was stable: 4.2 million (95% CI, 3.7-4.6 million) in 2006 and 3.8 million (95% CI, 3.6-4.0 million) in 2014. The number of delivery discharges with an HIV diagnosis was 4377 (95% CI, 3227-5527) in 2006 and 3915 (95% CI, 3410-4420) in 2014 (Table 2), and the rate per 10 000 deliveries among all women was 10.6 (95% CI, 8.1-13.1) in 2006 and 10.3 (95% CI, 9.0-11.6) in 2014 (Figure).

Figure.

Rates of delivery discharges with an HIV diagnosis, United States, 2006-2014. All results represent weighted samples. Data source: National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for 2006-2014.11

The crude RR for the temporal trend in an HIV diagnosis during 2006-2014 was not significant (0.99; 95% CI, 0.96-1.02) (Table 3), whereas the aRR for the temporal trend was significant (0.97; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99), implying heterogeneity in temporal trends in HIV diagnoses across sociodemographic groups. By sociodemographic group, we found homogenous declines with significant RRs and aRRs in discharges of white women, specifically those aged 25-34, Medicaid recipients, or those delivering in the South; of black women aged 25-34; and of privately insured women who were black, Hispanic, or aged 25-34 (Tables 4 and 5 and Figure).

Table 4.

Relative risk for temporal trends in an HIV diagnosis on discharge records at delivery by sociodemographic group, United States, 2006-2014a

| Characteristic | White (N = 15 674 710) |

Black (N = 15 674 710) |

Hispanic (N = 10 918 152) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 0.95 (0.92-0.99) | 0.94 (0.91-0.98) | 0.97 (0.94-1.01) | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) | 0.97 (0.92-1.02) | 0.97 (0.93-1.02) |

| Age at delivery, y | ||||||

| 13-24 | 0.97 (0.93-1.03) | 0.98 (0.93-1.03) | 0.99 (0.93-1.04) | 0.99 (0.94-1.05) | 0.97 (0.90-1.03) | 0.98 (0.92-1.04) |

| 25-34 | 0.94 (0.89-0.98) | 0.93 (0.88-0.97) | 0.99 (0.92-0.99) | 0.95 (0.92-0.99) | 0.97 (0.91-1.04) | 0.98 (0.92-1.04) |

| ≥35 | 0.95 (0.90-1.01) | 0.94 (0.89-0.99) | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) | 0.93 (0.86-1.00) | 0.93 (0.87-1.00) |

| Expected primary health insurer | ||||||

| Medicaid | 0.94 (0.90-0.98) | 0.93 (0.90-0.97) | 0.97 (0.94-1.01) | 0.96 (0.93-1.01) | 1.00 (0.94-1.07) | 0.96 (0.93-1.04) |

| Private | 0.96 (0.92-1.02) | 0.97 (0.92-1.02) | 0.95 (0.92-0.99) | 0.96 (0.92-0.99) | 0.91 (0.85-0.98) | 0.92 (0.86-0.98) |

| Self-pay, no charge, other | 0.95 (0.85-1.06) | 0.95 (0.86-1.06) | 1.00 (0.93-1.06) | 1.00 (0.94-1.07) | 0.92 (0.85-1.00) | 0.93 (0.86-1.01) |

| Census region | ||||||

| Northeast | 0.95 (0.89-1.01) | 0.95 (0.89-1.01) | 0.98 (0.96-1.02) | 0.97 (0.92-1.01) | 1.00 (0.95-1.05) | 0.97 (0.91-1.04) |

| Midwest | 1.07 (0.99-1.15) | 1.06 (0.99-1.13) | 1.01 (0.95-1.07) | 0.99 (0.93-1.06) | 0.94 (0.80-1.11) | 0.94 (0.80-1.11) |

| South | 0.94 (0.89-0.99) | 0.93 (0.88-0.98) | 0.98 (0.93-1.03) | 0.96 (0.92-1.01) | 0.97 (0.90-1.03) | 0.97 (0.91-1.03) |

| West | 0.92 (0.79-1.06) | 0.90 (0.78-1.03) | 0.96 (0.83-1.11) | 0.93 (0.82-1.08) | 0.95 (0.77-1.18) | 0.96 (0.77-1.19) |

Abbreviations: aRR, adjusted relative risk; RR, relative risk.

aN is number of delivery discharges. All results (ie, number of delivery discharges and RRs of an HIV diagnosis on discharge records at delivery) represent weighted samples. In each stratified multivariate analysis, we adjusted for the remaining sociodemographic characteristics, such as patient’s race/ethnicity, age at delivery, expected primary payer, medium annual household income for patient’s zip code, and census region. Data source: National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for 2006-2014.11

Table 5.

Relative risk for temporal trends in an HIV diagnosis on discharge records at delivery, by expected primary health insurer, United States, 2006-2014a

| Characteristic | Medicaid N = 15 153 246 |

Private N = 17 648 595 |

Self-Pay, No Charge, Other N = 2 210 933 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 0.99 (0.96-1.03) | 0.97 (0.93-1.00) | 0.97 (0.94-1.00) | 0.97 (0.94-0.99) | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) | 0.97 (0.94-1.02) |

| Age at delivery, y | ||||||

| 13-24 | 0.99 (0.95-1.03) | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) | 0.98 (0.93-1.03) | 0.98 (0.93-1.03) | 1.05 (0.97-1.14) | 1.08 (0.98-1.18) |

| 25-34 | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) | 0.96 (0.93-1.00) | 0.96 (0.93-0.99) | 0.96 (0.92-0.99) | 0.92 (0.87-1.00) | 0.93 (0.89-0.99) |

| ≥35 | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) | 0.94 (0.91-0.99) | 1.00 (0.96-1.04) | 0.99 (0.95-1.04) | 1.03 (0.93-1.13) | 0.99 (0.91-1.07) |

| Census region | ||||||

| Northeast | 0.98 (0.93-1.02) | 0.95 (0.91-1.00) | 0.97 (0.91-1.03) | 0.97 (0.92-1.02) | 1.03 (0.97-1.11) | 1.15 (1.06-1.25) |

| Midwest | 0.97 (0.90-1.05) | 0.98 (0.90-1.05) | 1.02 (0.94-1.10) | 1.04 (0.96-1.11) | 1.04 (0.90-1.19) | 1.02 (0.89-1.17) |

| South | 1.00 (0.94-1.05) | 0.96 (0.91-1.01) | 0.96 (0.92-1.01) | 0.95 (0.91-0.99) | 0.96 (0.91-1.02) | 0.93 (0.87-0.99) |

| West | 1.00 (0.86-1.13) | 0.96 (0.83-1.11) | 0.93 (0.83-1.03) | 0.92 (0.82-1.03) | 0.90 (0.78-1.04) | 0.89 (0.76-1.05) |

Abbreviations: aRR, adjusted relative risk; RR, relative risk.

aN is number of delivery discharges. All results (ie, number of discharges and RRs of an HIV diagnosis on discharge records at delivery) represent weighted samples. In each stratified multivariate analysis, we adjusted for the remaining sociodemographic characteristics, such as patient’s race/ethnicity, age at delivery, expected primary payer, median annual household income for patient’s zip code, and census region. Data source: National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for 2006-2014.11

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed 2006-2014 data from the NIS to estimate the number of delivery discharges with an HIV diagnosis that occurred in US hospitals overall and by sociodemographic group. According to our findings, the probability of having an HIV diagnosis, adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, declined on average 3% annually, with significant declines among some groups when stratified by race/ethnicity and primary payer. Overall, the probability of having an HIV diagnosis was greater among women who were black or Hispanic, aged ≥25, Medicaid recipients or uninsured, residing in areas with the lowest median annual household income (≤$37 999 in 2006, ≤$39 999 in 2014), or delivering in the Northeast and the South.

To our knowledge, this is the first US study to estimate the number of deliveries to women with an HIV diagnosis for each year during 2006-2014. Our estimates for 2007 and 2011 were somewhat lower than those published by Ewing et al10 (whereas our study estimated 5209 women with an HIV diagnosis who delivered in 2007 and 3758 women in 2011, Ewing et al estimated 5397 women in 2007 and 3855 women in 2011) because we used a conservative definition of deliveries (ie, ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes alone), whereas Ewing et al used a combination of ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes. However, our estimate for 2006 was approximately half as large as the estimate reported by Whitmore et al8 (our study estimated 4377 deliveries to women with an HIV diagnosis in 2006, whereas Whitmore et al estimated 8700 infants born to women with HIV infection in 2006). Such a discrepancy was expected, because we included only women with diagnosed HIV infection, whereas Whitmore et al included women with both diagnosed HIV infection (ranging from 82.7% of women living with HIV in 200624 to 87.8% in 2014)25 and undiagnosed HIV infection. In addition, we analyzed actual deliveries, including live births (about 99%) and stillbirths (1%),26 whereas Whitmore et al27 calculated pregnancy rates and assumed that all pregnancies resulted in live births. However, only about 65% of all pregnancies result with a live-born infant,28 and the live-birth rates among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women were similar during 2006-2012.29 After we adjusted our estimates to account for women with undiagnosed HIV infection and for the number of pregnancies that do not result in live births, we estimated 8142 (95% CI, 6003-10 282) pregnant women living with diagnosed or undiagnosed HIV infection in 2006, which is comparable to the estimate of 8700 women by Whitmore et al.27

The number of deliveries to women with an HIV diagnosis was also estimated in a 2017 article by Arab et al.30 However, that study included only ICD-9 code 042.x (HIV disease type 1), which—as our study demonstrated—accounted for only 18%-23% of deliveries to women with a diagnosis of HIV on their discharge records. In addition, the number of women who delivered infants in US hospitals reported by Arab et al was one-fifth of the number of registered births in the United States. Arab et al estimated that 7.8 million women delivered infants in US hospitals during 2003-2011, whereas national vital statistics reports estimated that 37.3 million women delivered infants in US hospitals during that period,31 indicating that Arab et al likely reported unweighted results from the NIS data set.

Our findings on sociodemographic factors are consistent with previous analyses of deliveries to women with HIV infection10,29,30 and of all US women living with diagnosed HIV infection.24,25,32,33 Similar to those studies, our study identified a higher probability of diagnosed HIV infection on delivery discharges among non-Hispanic black women, Medicaid recipients, women living in areas with the lowest median annual household income, and women who delivered in the Northeast or South.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to examine temporal trends in diagnosed HIV infection at delivery by sociodemographic group and to demonstrate significant declines in RR of having an HIV diagnosis on discharge records among white women, specifically white women aged 25-34, receiving Medicaid, or delivering in the South; black women aged 25-34 or privately insured; privately insured Hispanic women; and privately insured women aged 25-34. Although the sociodemographic characteristics for most patients were well reported for all years, data on race/ethnicity were missing or invalid for a substantial percentage (21.1%) of delivery discharge records in 2006. In 2014, however, only 6.4% of data on race/ethnicity were missing or invalid. Improved reporting of race/ethnicity over time was predominantly due to an increasing number of states that make this information publicly available in their inpatient data sets34 (during 2006-2007, 7 states did not report data on race/ethnicity for hospitalizations; during 2008-2014, 2 or 3 states did not report data on race/ethnicity). We observed that the geographic distribution of states with missing data on race/ethnicity was random and neighboring states, with comparable sociodemographic characteristics, reported race/ethnicity.34 We also assessed temporal trends in HIV diagnoses by excluding states without race/ethnicity data available for all years during 2006-2014 and found similar RRs (aRR = 0.96; 95% CI, 0.93-0.99) compared with including states with race/ethnicity reported in any year (aRR = 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99) (Table 3). Combined, these findings support estimating race/ethnicity trends in women with an HIV diagnosis in this analysis.

The number of women with a diagnosis of HIV-2 on their discharge records was higher in our study than in previous studies. The most recent report of HIV-2 diagnoses in the United States, published in 2011, found 24 pregnant women with an HIV-2 diagnosis during 1987-2009, with most cases of HIV-2 reported during 2000-2009.35 In contrast, our study estimated 123 (95% CI, 98-148) delivery discharges with a diagnosis of HIV-2 during 2006-2014, of which 46 (95% CI, 44-48) delivery discharges occurred during 2006-2009. The 2011 report may have underestimated the number of women with a diagnosis of HIV-2 as a result of inadequate data on test results and incomplete reporting of HIV-2 by laboratories and HIV surveillance programs.35 In contrast, our study could have overestimated the number of women with diagnosed HIV-2 infection if some ICD-9-CM diagnoses were not confirmed at the time of hospital discharge.

Limitations

This analysis had several limitations. First, we almost certainly underestimated the actual number of deliveries among women with an HIV diagnosis, because NIS did not include 1.0%-1.5% of women who delivered outside a hospital.31,36 Second, we underestimated the total number of delivery discharges with HIV infection (diagnosed and undiagnosed) because we did not have information on women with undiagnosed HIV infection. In addition, the proportion of women who lived with undiagnosed HIV infection declined from 17.3% in 200624 to 12.2% in 2014.25 Thus, the rate of delivery discharges with HIV infection could have further decreased. Third, we had no information on whether women learned of their HIV status before delivery, which would have helped preventing the in utero and intrapartum mother-to-child transmission. However, a 2017 study in Florida documented that nearly 97% of mothers of HIV-exposed infants born during 2007-2014 were diagnosed with HIV before or during pregnancy.37 Finally, NIS lacked mother-to-child linkages, which limited our ability to analyze trends in perinatal transmission of HIV among children delivered during 2006-2014.

Despite these limitations, our study contributes to the literature by synthesizing a comprehensive definition of an HIV diagnosis and a nationally representative sample to identify deliveries to all women with an HIV diagnosis in US hospitals from 2006 to 2014 overall and by sociodemographic group. Estimates of diagnosed HIV infection among women delivering infants are crucial for understanding trends and characteristics of mother–infant pairs that could benefit from prevention services.

Conclusions

From 2006 to 2014, the probability of having an HIV diagnosis at delivery declined among several sociodemographic groups of women. High-impact prevention programs and interventions, tailored to sociodemographic groups in which rates of diagnosed HIV infection have not declined or the probability of an HIV diagnosis at delivery is higher than in other groups, can reduce the risk of mother-to-child HIV transmission by offering appropriate medical care before, during, and after delivery and by supporting adherence to antiretroviral treatment among women and infants exposed to HIV infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance’s Partnership and Evaluation Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for technical assistance with Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project data.

Preliminary findings from this research were presented at the 2019 National HIV Prevention Conference in Atlanta, Georgia, March 19, 2019. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Maria Vyshnya Aslam https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0036-3851

References

- 1. Peters H., Francis K., Sconza R. et al. UK mother-to-child HIV transmission rates continue to decline: 2012-2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(4):527-528. 10.1093/cid/ciw791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations of the US Public Health Service Task Force on the use of zidovudine to reduce perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;43(RR-11):1-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wortley PM., Lindegren ML., Fleming PL. Successful implementation of perinatal HIV prevention guidelines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50(RR06):17-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG committee opinion—scheduled cesarean delivery and the prevention of vertical transmission of HIV infection. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;73(3):279-281. 10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00412-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations for assisting in the prevention of perinatal transmission of human T-lymphotropic virus type III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1985;34(48):731-732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nesheim S., Taylor A., Lampe MA. et al. A framework for elimination of perinatal transmission of HIV in the United States. Pediatrics. 2012;130(4):738-744. 10.1542/peds.2012-0194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. US Department of Health and Human Services CDC-RFA-PS12-1201. Comprehensive HIV prevention programs for health departments: catalog of federal domestic assistance. No. 93.940. 2012. Accessed March 3, 2020. https://www.federalgrants.com/Comprehensive-HIV-Prevention-Programs-for-Health-Departments-30487.html

- 8. Whitmore SK., Zhang X., Taylor AW., Blair JM. Estimated number of infants born to HIV-infected women in the United States and five dependent areas, 2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(3):218-222. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182167dec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Taylor AW., Nesheim SR., Zhang X. et al. Estimated perinatal HIV infection among infants born in the United States, 2002-2013. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(5):435-442. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.5053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ewing AC., Datwani HM., Flowers LM., Ellington SR., Jamieson DJ., Kourtis AP. Trends in hospitalizations of pregnant HIV-infected women in the United States: 2004 through 2011. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):499.e1-8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.05.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) HCUP National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS), 2006-2014. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Accessed February 23, 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp [PubMed]

- 12. Heslin KC., Owens PL., Karaca Z., Barrett ML., Moore BJ., Elixhauser A. Trends in opioid-related inpatient stays shifted after the US transitioned to ICD-10-CM diagnosis coding in 2015. Med Care. 2017;55(11):918-923. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Trend Weights for 1993-2011 HCUP NIS Data. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2015 http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/trendwghts.jsp [PubMed]

- 14. Hornbrook MC., Whitlock EP., Berg CJ. et al. Development of an algorithm to identify pregnancy episodes in an integrated health care delivery system. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):908-927. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00635.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tao G., Patterson E., Lee LM., Sansom S., Teran S., Irwin KL. Estimating prenatal syphilis and HIV screening rates for commercially insured women. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(2):175-181. 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). Accessed January 20, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm

- 17. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Acute inpatient prospective payment system. 2017. Accessed January 20, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html?redirect=/acuteinpatientpps

- 18. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare program; changes to the hospital inpatient prospective payment systems and fiscal year 2008 rates. Fed Regist. 2007;72(162):47129-48175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project NIS description of data elements. 1980-2014. Accessed January 10, 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdde.jsp

- 20. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Appendix A—clinical classifications software—diagnoses (January 1980 through September 2015). Revised 2016. Accessed January 10, 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/AppendixASingleDX.txt

- 21. Lurie P. Official authorized addenda: human immunodeficiency virus infection codes and official guidelines for coding and reporting ICD-9-CM. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1994;30:11-19. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stata 14 Version 14.0. StataCorp; 2015. Accessed January 20, 2019. https://www.stata.com/products

- 23. Houchens R., Ross D., Elixhauser A. Final Report on Calculating National Inpatient Sample (NIS) Variances for Data Years 2012 and Later. HCUP Methods Series Report # 2015-09 ONLINE. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015. Accessed January 10, 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/2015_09.jsp

- 24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas, 2011. HIV Surveill Suppl Rep. 2013;18(5):1-47. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas, 2015. HIV Surveill Suppl Rep. 2017;22(2):1-63. [Google Scholar]

- 26. MacDorman MF., Gregory EC. Fetal and perinatal mortality: United States, 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(8):1-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Whitmore SK., Taylor AW., Espinoza L., Shouse RL., Lampe MA., Nesheim S. Correlates of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in the United States and Puerto Rico. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e74-e81. 10.1542/peds.2010-3691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ventura SJ., Curtin SC., Abma JC., Henshaw SK. Estimated pregnancy rates and rates of pregnancy outcomes for the United States, 1990-2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;60(7):1-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haddad LB., Wall KM., Mehta CC. et al. Trends of and factors associated with live-birth and abortion rates among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(1):71.e1-71.e16. 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.09.079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arab K., Spence AR., Czuzoj-Shulman N., Abenhaim HA. Pregnancy outcomes in HIV-positive women: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295(3):599-606. 10.1007/s00404-016-4271-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hamilton BE., Martin JA., Osterman MJ., Curtin SC., Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(12):1-64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, by race/ethnicity, 2003-2007. HIV/AIDS Surveill Suppl Rep. 2009;14(2):1-3. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas, 2014. HIV Surveill Suppl Rep. 2016;21(4):1-87. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Central distributor SID: availability of data elements by year, 1990-2017. Accessed February 20, 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/state/siddist/siddist_ddeavailbyyear.jsp

- 35. Torian LV., Selik RM., Branson B. et al. HIV-2 infection surveillance—United States, 1987-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(29):985-988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heron M., Hoyert DL., Murphy SL. et al. Births: final data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;57(7):1-104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Trepka MJ., Mukherjee S., Beck-Sagué C. et al. Missed opportunities for preventing perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus, Florida, 2007-2014. South Med J. 2017;110(2):116-128. 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]