Abstract

Although writing is a valued public health competency, authors face a multitude of barriers (eg, lack of time, lack of mentorship, lack of appropriate instruction) to publication. Few writing courses for applied public health professionals have been documented. In 2017 and 2018, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention partnered to implement a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Intensive Writing Training course to improve the quality of submissions from applied epidemiologists working at health departments. The course included 3 webinars, expert mentorship from experienced authors, and a 2-day in-person session. As of April 2020, 39 epidemiologists had participated in the course. Twenty-four (62%) of the 39 epidemiologists had submitted manuscripts, 17 (71%) of which were published. The program’s evaluation demonstrates the value of mentorship and peer feedback during the publishing process, the importance of case study exercises, and the need to address structural challenges (eg, competing work responsibilities or supervisor support) in the work environment.

Keywords: workforce development, epidemiology, writing training, public health

One of the public health professional competencies is communicating public health content through writing.1 Writing is practiced in school and continues in academic positions with an emphasis on publishing research. Writing may improve through practice and mentorship, but applied epidemiology positions often do not emphasize writing for professional audiences. Professional writing is not part of job descriptions for applied epidemiology positions; government staffing, outside of pure research settings, rarely includes time or funds to publish findings; and mentors for writing are not often available. Thus, applied epidemiologists have few opportunities or encouragement for continuing education or practice to improve professional writing skills.

Literature on professional writing programs is robust. Writing across the curriculum,2 distance learning,3 collaborative writing applications,4 and online writing centers5 have been described, some extensively. Most of these strategies are being applied in academic settings rather than on the job, and few strategies have been applied in the health field.2-5 A systematic review of health-related journals from 1990 to 2013 found 12 studies on writing for publication.6 These studies focused primarily on strategies to build writing skills.7-18 Such studies were evaluated primarily on the basis of increased publication output, often an increase from none to one, with little information about the publications’ quality or the value of the educational components. These findings suggest that studies evaluating writing trainings are scarce and of low quality, limiting knowledge on the effectiveness of existing programs.6 None of these studies focused on applied epidemiologists. None addressed structural barriers for public health professionals, such as limited resources, absence of supervisor support, or the fact that writing for publication is rarely included in job descriptions or in legislative or contractual funding language.19-24 Although written communication skills are required for entry-level epidemiologists,25 such skills are used more for internal reports than for disseminating information through published literature.7,26

In response to the need to improve writing skills among applied epidemiologists, in October 2016, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) partnered to develop a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Intensive Writing Training course to improve the quality of submissions by applied epidemiologists. CSTE offered the course in 2017 and 2018. Demand for the program was high: 78 applications were submitted in 2017 for 21 spots (cohort 1), and 57 applications were submitted in 2018 for 18 spots (cohort 2). Despite interest in the program, the course was not continued after 2018 because of a lack of funding. In this case study, we share lessons learned from the training, evaluation, and monitoring of the participants. These lessons can inform best practices for future writing courses and resource allocation to support writing activities among applied public health professionals.

Intensive Writing Training Course

Participant Recruitment and Selection

In February and December 2017, CSTE advertised the training course to state, territorial, local, and tribal epidemiologists who were CSTE members and to the National Association of County and City Health Officials epidemiology workgroup via email announcements and social media. Eligibility required that applicants (1) had never published in MMWR as a first or senior author; (2) had published <5 professional articles as a first or senior author; (3) were employed at a state, territorial, local, or tribal agency; and (4) had supervisory and agency support to participate in the course. Applicants were required to describe their interest in the course, outline their proposed manuscript, and provide a letter of support from their agency. CSTE notified selected participants of acceptance to the course, which included webinars, an in-person session, and the assignment of an expert mentor who provided one-on-one guidance to complement the support the participants received at their agency. CSTE invited applicants who were not selected to participate in publicly available webinars.

Training Approach

Participants viewed 3 required educational webinars about the writing process and submission requirements specific to MMWR in advance of attending a 2-day in-person session in Atlanta, Georgia (May 10-11, 2017, and April 10-11, 2018). MMWR staff members developed and taught the webinar content. The 3 webinars27 were publicly available and promoted by CSTE and CDC. Before the in-person session, participants worked with their mentors to develop a first draft of their manuscript. Based on lessons learned from cohort 1, in which participants did not bring a complete draft manuscript to the in-person session, cohort 2 participants were expected to have a complete draft manuscript to discuss at the in-person session.

The in-person session included group feedback meetings, in which preassigned groups of participants met to provide feedback on each other’s drafts and share writing experiences; dedicated one-on-one time with expert mentors; a case study, in which participants were able to view and work through an example of a submitted manuscript with edits; and additional presentations on topics such as creating a promotion plan for the publication, working with the press, and understanding the legal implications of publishing their data. All participants set goals and identified sources of motivation and accountability to support continued progress on their manuscript after completing the course. After the in-person session, participants continued to work with their expert mentors, who established periodic telephone appointments to track progress, review the latest versions of the manuscripts, and respond to questions about the manuscript or the writing process in general. This formal mentorship concluded 6 months after the in-person session.

Methods

Evaluation and Analysis

The evaluation included 3 approaches to assess the participants: (1) webinar evaluations, completed immediately after each of the 3 webinars; (2) session evaluation, completed within 1 month of the in-person session; and (3) periodic check-in emails, commencing 2 months after the in-person session.

The webinar and training evaluations measured participants’ level of confidence in their knowledge, skills, and abilities linked to the course’s learning objectives, by using 5-point Likert scales (not at all confident to very confident and not effective to extremely effective). The in-person session evaluation also collected qualitative data through 3 open-ended questions:

How will you use the information learned in the training?

In what ways could the training be improved?

Do you have any additional comments on the overall training?

CSTE continued to follow participants’ progress by email, requesting updates on participants’ manuscript progress. As of April 2020, CSTE had collected email updates from cohort 1 seven times during the 33-month follow-up and from cohort 2 seven times during the 21-month follow-up. Monitoring of participants’ progress is ongoing until participants receive a manuscript determination or indicate discontinued efforts.

CSTE analyzed all quantitative data from the webinar evaluations and in-person session evaluations by using Qualtrics and Microsoft Excel. Two people (J.A., M.P.) coded the qualitative data thematically. The coders discussed and resolved any differences by recoding to a single theme.

Outcomes

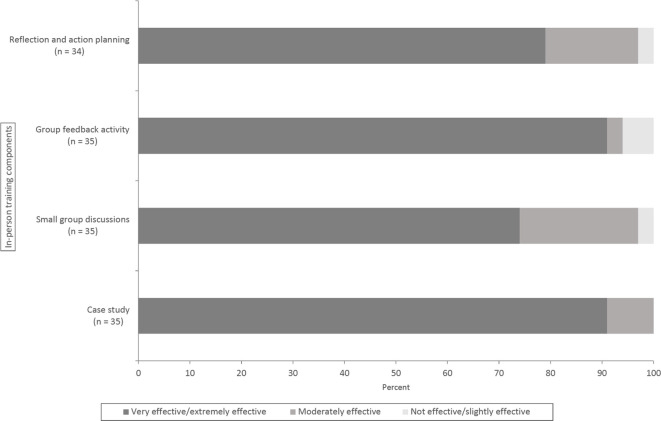

A total of 39 epidemiologists completed the course: 21 participants in cohort 1 (2017) and 18 participants in cohort 2 (2018). Thirty-seven of the 39 participants evaluated the in-person session, for a response rate of 94.9%. All participants in both cohorts reported that they would recommend the course to others, and 35 (95%) participants said the course was useful to their work (Table). All participants reported that they would submit a manuscript to MMWR by the end of the year after the course was completed. Most participants in both cohorts rated the group feedback session (n = 32/35, 91%) and the case study (n = 32/35, 91%) as extremely effective or very effective, followed by the reflection and action planning activities (n = 27/35, 77%), and the small-group discussions (n = 26/35, 74%) (Figure 1).

Table.

Participant evaluation of the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MMWR Intensive Writing Training course, 2017-2018a

| Evaluation Statement | Responses No. (%) (n = 37) |

|---|---|

| Overall Training Evaluation | |

| I would recommend the training to others | |

| Agree/strongly agree | 37 (100) |

| Neutral | 0 |

| Strongly disagree/disagree | 0 |

| The training content was useful to my work | |

| Agree/strongly agree | 35 (95) |

| Neutral | 2 (5) |

| Strongly disagree/disagree | 0 |

| Mentor Evaluation | |

| I used my mentor for the development of an MMWR submission | |

| Agree/strongly agree | 33 (89) |

| Neutral | 2 (5) |

| Strongly disagree/disagree | 2 (5) |

| I value my mentor’s opinion | |

| Agree/strongly agree | 35 (95) |

| Neutral | 2 (5) |

| Strongly disagree/disagree | 0 |

| I had adequate time with my mentor | |

| Agree/strongly agree | 28 (76) |

| Neutral | 6 (14) |

| Strongly disagree/disagree | 4 (10) |

| My mentor was engaged and involved in my work | |

| Agree/strongly agree | 32 (86) |

| Neutral | 2 (5) |

| Strongly disagree/disagree | 3 (8) |

Abbreviation: MMWR, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

aThe Intensive Writing Training course provided on-the-job scientific writing instruction and mentorship for selected applied epidemiologists working on a manuscript. The course was offered in 2017 and 2018. Each course included 3 webinars, expert mentorship from experienced authors, and a 2-day in-person session.

Figure 1.

Participant-reported value of in-person training components in the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Intensive Writing Training course for applied epidemiologists, 2017-2018. The Intensive Writing Training course provided on-the-job scientific writing instruction and mentorship for selected applied epidemiologists working on a manuscript. The course was offered in 2017 and 2018. Each course included 3 webinars, expert mentorship from experienced authors, and a 2-day in-person session.

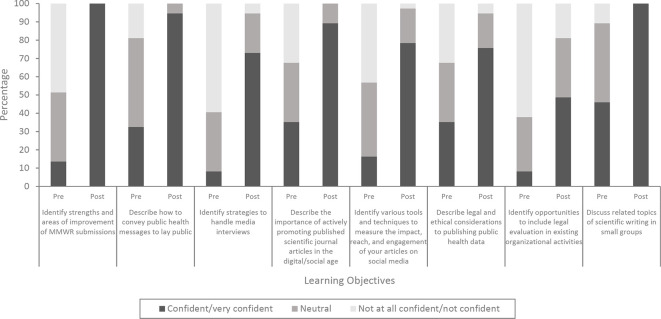

Participant confidence in their knowledge, skills, and abilities related to the course’s learning objectives increased after completing the course (Figure 2). Participants recommended program improvements of completing a manuscript draft before the in-person session, reserving more time with expert mentors, and enhancing the group feedback component by reviewing their peers’ drafts in advance.

Figure 2.

Participant confidence pre- and post-training, by learning objective, in the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Intensive Writing Training course for applied epidemiologists (n = 37), 2017-2018. The Intensive Writing Training course provided on-the-job scientific writing instruction and mentorship for selected applied epidemiologists working on a manuscript. The course was offered in 2017 and 2018. Each course included 3 webinars, expert mentorship from experienced authors, and a 2-day in-person session.

Manuscript progress among participants varied greatly. As of April 2020, 24 of 39 (62%) participants had submitted their manuscripts for publication. Of the 24 manuscripts submitted, 17 were accepted, 4 were rejected, 2 were under review, and 1 had been withdrawn. Of the 15 remaining manuscripts, 7 were complete drafts and 8 were incomplete.

Qualitative data from the evaluation and check-in emails resulted in 3 themes related to the course: writing, communication, and experiential learning.

Writing

Participants noted changes in their writing abilities, such as learning to write more clearly and succinctly. Many participants also reported that the writing skills they developed during the course facilitated their manuscript development and submission.

Communication

Communication emerged as a theme in several ways. Participants highlighted communicating and networking with one another, communicating within their agency, and communicating their findings to the public. Participants noted the value of connecting with peers at other agencies to expand their support network. They felt the course was valuable to their professional development. Participants also mentioned their intention to share their newly acquired knowledge and skills with colleagues at their agency. In addition, participants suggested a desire to encourage and advocate for a culture of publication at their agency. Lastly, participants reported that they learned strategies for communicating to the public, such as how to communicate with news outlets or promote their message using social media.

Experiential Exercises

The most valued training components were experiential learning opportunities. Both the group feedback sessions, in which participants worked together to edit and improve manuscript drafts, and the case study, in which participants viewed and worked through a sample manuscript submission with reviewer edits, were viewed by participants as helpful to the manuscript development process.

Qualitative data from the check-in emails revealed the common barriers and facilitators to publication that participants experienced as they sought publication during the months after course completion.

Barriers to publication

Participants noted several barriers that prevented them from publishing their manuscripts within their intended time frame. First, a lack of data halted efforts early in the process. Second, for participants who did have access to data, competing priorities (eg, data requests, grants, or urgent field investigations) and changes to job responsibilities were common barriers. Lastly, after overcoming these barriers and completing their manuscript, many participants felt the process took so long that their data and manuscript were no longer relevant.

Facilitators to publication

The expert mentors’ technical expertise and their roles as monitors of participants’ progress were important facilitators of the writing process. Although participants’ competing demands were a challenge, working with a mentor helped participants set deadlines and prioritize manuscript efforts. Participants also noted check-in emails as an accountability prompt.

Lessons Learned

This writing course demonstrated the merits of mentoring novice authors on successful steps for publishing an article in MMWR. We summarize the lessons learned from implementing 2 cohorts of the CDC/CSTE MMWR Intensive Writing Training course.

Both quantitative and qualitative evaluation data demonstrate the value and appreciation of mentorship, including expert mentorship and the informal peer-to-peer mentorship among participants. Although mentorship was valued by participants, serving as a mentor in addition to normal job responsibilities can limit the availability and engagement of the mentor to support the participant’s progress. Future courses should assess mentor availability and workload, in addition to their subject matter expertise, to assure accessibility for the participants.

The in-person group feedback activity allowed participants to discuss their own manuscripts and writing experiences. The communal discussion provided insight into the writing and submission process and helped participants manage their own expectations. Although plenty of time was dedicated to the group feedback sessions, CSTE suggests a useful improvement would be to require participants to share their draft manuscript with their groups in advance of meeting to better use the time for critique and discussion rather than reading the drafts. In addition, fostering continued discussion among the groups after the in-person feedback sessions through telephone calls or virtual meetings should be considered as a beneficial source of mentorship and accountability.

Participants indicated that the case study exercise was a useful component and improved participant confidence to identify strengths and areas of improvement of MMWR submissions. The review and critique of sample manuscripts fostered discussion of strategies for clear, concise writing and the formatting requirements of MMWR. The ability to view submitted manuscripts with feedback is a low-cost activity that should be considered in future writing courses.

The goal-oriented approach harnessed the participants’ intention to complete and submit a manuscript. Regular communication with expert mentors helped participants set deadlines for progress. The group discussed anticipated challenges and strategies for success and identified sources of motivation to further support participants. At the conclusion of the in-person session, each participant created an action plan outlining next steps for manuscript progress. After the course, the monitoring email check-ins were an opportunity to hold participants accountable and share strategies to mitigate barriers to progress. The supportive goal-oriented course approach paired with periodic accountability reminders provided a structure for progress.

Although the expert mentorship helped participants develop and finalize their manuscripts, the mentorship appeared to be more beneficial for cohort 2, when participants had a preexisting manuscript draft to share and discuss, than for cohort 1, when participants did not have a draft ready to share and discuss. Some participants needed additional support early in the writing process to develop and recognize the central hypothesis and public health implications of their work. Working through the 3 suggested “sidebar boxes” of the MMWR (What is already known? What is added by this report? What are the implications for public health practice?) was a useful first task for participants to organize their thoughts and establish a context for the work to be described.

Participants had approximately 6 months to work with their expert mentors, which was insufficient for most participants to receive mentorship through to submission. Participants experienced the challenge of competing priorities, which slow analytic and writing progress, and favored a longer mentorship period until the manuscript is submitted. It takes time to move manuscripts through the review process required by each author’s organization, often leading to months-long delays for manuscripts with authors from multiple organizations. To effectively use and engage mentorship as part of the program, consideration should be given to the lengthy interval between manuscript conception and submission.

Other lessons learned related to the structural realities of the work environment. Although participants intended to submit their manuscripts by the end of the year, most did not. This delay may have indicated insufficient motivation and commitment to the process of submitting a manuscript. One stipulation in the process of selecting participants for each cohort was an assurance that the participants’ supervisors would support them by approving time for them to write, participate in conference calls, and attend the in-person session. Even when participants felt supported by their supervisors, work responsibilities such as data requests, grants, and outbreaks were competing priorities that affected manuscript progress and program participation. The attempt to mitigate these structural barriers by formalizing supervisor support was insufficient, suggesting that future courses should incorporate new ways to address these challenges.

Writing trainings for applied public health professionals should consider using peer or expert mentorship or both, reviewing edited materials, and integrating components of accountability and goal setting. The mentoring relationships prove most useful when implemented after a first draft is attempted. Activities such as group feedback and case studies allow for real-time feedback and discussion of successful writing strategies that ultimately foster improved skills for quality writing. Lastly, courses for applied public health professionals must incorporate innovative ways to target the structural barriers to writing for publication.

Acknowledgments

CSTE values the partnership with CDC to provide this course. The authors thank Charlotte Kent, who was instrumental in the creation and delivery of the MMWR Intensive Writing Training course.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was supported in part by CDC cooperative agreement #5U38OT000143.

ORCID iD

Jessica Arrazola https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5427-0925

References

- 1. Council on Education for Public Health Accreditation Criteria: Schools of Public Health & Public Health Programs. Council on Education for Public Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hawks SJ., Turner KM., Derouin AL., Hueckel RM., Leonardelli AK., Oermann MH. Writing across the curriculum: strategies to improve the writing skills of nursing students. Nurs Forum. 2016;51(4):261-267. 10.1111/nuf.12151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Duncanson K., Webster EL., Schmidt DD. Impact of a remotely delivered, writing for publication program on publication outcomes of novice researchers. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18(2):4468. 10.22605/RRH4468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Archambault PM., van de Belt TH., Kuziemsky C. et al. Collaborative writing applications in healthcare: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD011388. 10.1002/14651858.CD011388.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. White BJ., Lamson KS. The evolution of a writing program. J Nurs Educ. 2017;56(7):443-445. 10.3928/01484834-20170619-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Galipeau J., Moher D., Campbell C. et al. A systematic review highlights a knowledge gap regarding the effectiveness of health-related training programs in journalology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(3):257-265. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dixon N. Writing for publication—a guide for new authors. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001;13(5):417-421. 10.1093/intqhc/13.5.417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Driscoll J., Aquilina R. Writing for publication: a practical six step approach. Int J Orthopaed Trauma Nurs. 2011;15(1):41-48. 10.1016/j.ijotn.2010.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moos DD. “Novice authors … what you need to know to make writing for publication smooth.” J Perianesth Nurs. 2011;26(5):352-356. 10.1016/j.jopan.2011.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Meadows KA. So you want to do research? 6: reporting research. Br J Community Nurs. 2004;9(1):37-41. 10.12968/bjcn.2004.9.1.11935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Driscoll J., Driscoll A. Writing an article for publication: an open invitation. J Orthopaed Nurs. 2002;6(3):144-152. 10.1016/S1361-3111(02)00053-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kramer B., Libhaber E. Writing for publication: institutional support provides an enabling environment. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:115. 10.1186/s12909-016-0642-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baldwin C., Chandler GE. Improving faculty publication output: the role of a writing coach. J Prof Nurs. 2002;18(1):8-15. 10.1053/jpnu.2002.30896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee A., Boud D. Writing groups, change and academic identity: research development as local practice. Stud Higher Educ. 2003;28(2):187-200. 10.1080/0307507032000058109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Steinert Y., McLeod PJ., Liben S., Snell L. Writing for publication in medical education: the benefits of a faculty development workshop and peer writing group. Med Teach. 2008;30(8):e280-e285. 10.1080/01421590802337120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Henninger DE., Nolan MT. A comparative evaluation of two educational strategies to promote publication by nurses. J Contin Educ Nurs. 1998;29(2):79-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Phadtare A., Bahmani A., Shah A., Pietrobon R. Scientific writing: a randomized controlled trial comparing standard and on-line instruction. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9(1):27. 10.1186/1472-6920-9-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murray R., Newton M. Facilitating writing for publication. Physiotherapy. 2008;94(1):29-34. 10.1016/j.physio.2007.06.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pittman J., Stahre M., Tomedi L., Wurster J. Barriers and facilitators to scientific writing among applied epidemiologists. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2017;23(3):291-294. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nelms BC. Writing for publication: your obligation to the profession. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31(4):423-424. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists 2013 national assessment of epidemiology capacity: findings and recommendations for chronic disease, maternal and child health, and oral health. Published 2014. Accessed April 22, 2020 http://www.cste2.org/docs/CSTE_2013_national_assessment_of_epidemiology_capacity_findings.pdf

- 22. Wills CE. Strategies for managing barriers to the writing process. Nurs Forum. 2007;35(4):5-13. 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2000.tb01224.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Keen A. Writing for publication: pressures, barriers and support strategies. Nurse Educ Today. 2007;27(5):382-388. 10.1016/j.nedt.2006.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pololi L., Knight S., Dunn K. Facilitating scholarly writing in academic medicine: lessons learned from a collaborative peer mentoring program. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(1):64-68. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21143.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists CDC/CSTE competencies for applied epidemiologists in governmental public health agencies. Published 2008. Accessed April 22, 2020 http://www.cste2.org/webpdfs/AppliedEpiCompwcover.pdf

- 26. Brownson RC., Baker EA., Leet TL., Gillespie KN., True WR. Evidence-Based Public Health. 2nd ed Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists Webinar library. Accessed July 23, 2019 https://www.cste.org/page/WebinarLibrary