Abstract

Proteins that terminally fail to acquire their native structure are detected and degraded by cellular quality control systems. Insights into cellular protein quality control are key to a better understanding of how cells establish and maintain the integrity of their proteome and of how failures in these processes cause human disease. Here we have used genetic code expansion and fast bio‐orthogonal reactions to monitor protein turnover in mammalian cells through a fluorescence‐based assay. We have used immune signaling molecules (interleukins) as model substrates and shown that our approach preserves normal cellular quality control, assembly processes, and protein functionality and works for different proteins and fluorophores. We have further extended our approach to a pulse‐chase type of assay that can provide kinetic insights into cellular protein behavior. Taken together, this study establishes a minimally invasive method to investigate protein turnover in cells as a key determinant of cellular homeostasis.

Keywords: bio-orthogonal reactions, fluorescent probes, genetic code expansion, interleukins, protein folding

Biosynthesis and degradation of proteins are critical for every cell. Using genetic code expansion and fast bio‐orthogonal reactions, we have developed a fluorescence‐based approach that allows monitoring of protein turnover in mammalian cells in a minimally invasive manner.

Introduction

In order to become biologically active, most proteins have to adopt defined three‐dimensional structures: that is, to fold. Protein folding is among the most fundamental processes of self‐organization in living systems and at the same time is highly complex: in a correctly structured protein, thousands of atoms each adopt a well‐defined position in space.1 Accordingly, cells have developed a comprehensive machinery of protein folding helpers, molecular chaperones, to aid protein folding—but also to scrutinize its success and to degrade proteins that do not achieve their native structure.2 Failures in these processes give rise to protein misfolding disorders such as Parkinson's or Alzheimer's diseases.3

In a mammalian cell, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is specialized in the production and folding of membrane and secreted proteins.4 These proteins mediate cellular communication, transport processes, and coordinated development, and in total make up more than one third of a typical mammalian proteome.5 As such, the ER can be considered a bona fide protein‐folding factory in the cell, which also sets the standards that determine whether a protein shall be transported to the cell surface or shall be degraded if it fails to fold.6 This process is termed ER quality control (ERQC). Generally, proteins that fail to acquire their native structures in the ER are eliminated in a process called ER‐associated degradation (ERAD).7 ERAD includes recognition of misfolded proteins in the ER, their retro‐translocation back to the cytosol, ubiquitination, and subsequent degradation by the major proteolytic machinery of the cell, the proteasome.7, 8 Its fundamental role in cell biology, and its immediate involvement in human disease, have spurred great interest in understanding the molecular basis of ERAD,9 as well as in developing techniques to monitor this process.10, 11, 12

The site‐specific incorporation of unnatural amino acids (UAAs) through genetic code expansion and their subsequent chemoselective labeling with fluorescent probes might present an ideal tool with which to monitor ERAD and protein turnover in general.13 Recent years have seen tremendous progress in the development of rapid and selective bio‐orthogonal reactions such as inverse‐electron‐demand Diels–Alder cycloaddition (iEDDAC) between strained dienophiles and tetrazines.14, 15, 16, 17 Unnatural amino acids bearing strained alkene or alkyne motifs, such as bicyclo[6.1.0]nonyne (BCNK)16, 18 and trans‐cyclooctene (TCOK),16, 17 have been incorporated site‐specifically into proteins in Escherichia coli and in mammalian cells with the aid of specific and orthogonal pyrrolysyl‐tRNA synthetase (PylRS/tRNACUA) pairs. Rapid iEDDAC with tetrazine fluorophore conjugates allows the site‐specific and selective labeling of proteins in living cells with a diverse range of fluorophores,16, 17 and has been used for imaging of cell‐surface and intracellular proteins,19, 20, 21, 22, 23 as well as to control enzyme activities in cells.24

Here we have made use of this potential and developed a fluorescence‐based assay for monitoring protein turnover in mammalian cells. We have site‐specifically incorporated BCNK16, 18 into low‐abundance mammalian proteins by using an efficient PylRS variant, which allows for fast and selective protein labeling with tetrazine‐fluorophore conjugates. This extends the arsenal of methods that have been developed in recent years to monitor protein turnover in cells25, 26, 27 by a fluorescence‐based approach that relies on rapid bio‐orthogonal reactions. As model substrates, we have used members of the human interleukin 12 (IL‐12) family.28, 29 Interleukins are key signaling molecules in our immune system and, as such, understanding of their biogenesis and degradation is of great interest. Like other secreted proteins, interleukins are produced in the ER, each IL‐12 family member being a heterodimeric protein made up of an α and a β subunit.28, 29 It has recently been shown that both IL‐12α and IL‐23α fail to fold in the absence of their β subunits and are thus rapidly degraded,30, 31, 32 providing native clients of ER quality control. Our data show that incorporation of BCNK and site‐specific fluorophore labeling of IL‐12α and IL‐23α preserves their normal biogenesis processes and provides an ideal tool with which to monitor protein turnover in mammalian cells.

Results and Discussion

Unnatural amino acids can be incorporated into interleukin subunits while maintaining their wild‐type behavior

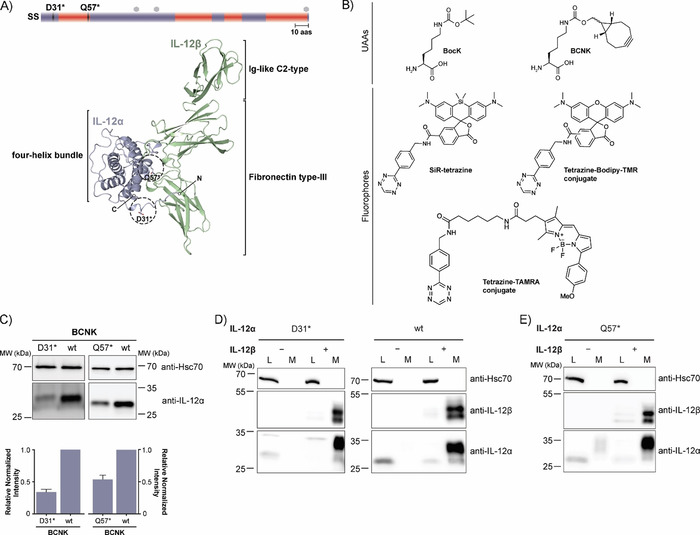

A major advantage of genetic code expansion is that it offers the capability to label any position within a polypeptide sequence with only minimal modifications to the protein under scrutiny. Here we have used a selective and highly efficient PylRS variant (Y271G, C313V, Methanosarcina barkeri numbering, dubbed BCNKRS, Figure S1 A in the Supporting Information)33 for expression of low‐abundance interleukins bearing BCNK at defined positions. Beginning with the α subunit of IL‐12 (IL‐12α, Figure 1 A), we searched for a suitable position at which to introduce BCNK (Figure 1 B). Criteria were complete solvent‐exposure in the native heterodimeric IL‐12 structure as well as no predicted interference with IL‐12β heterodimerization.34 Asp31 (D31) and Gln57 (Q57) fulfilled these criteria (Figure 1 A). By using BCNKRS and BCNK we could achieve significant expression for the IL‐12α constructs in which D31 or Q57 were replaced by an amber stop codon (D31* or Q57*, respectively). Expression did not vary significantly between 0.1 and 1 mm BCNK (Figure S1B). At 0.25 mm BCNK, expression levels of IL‐12α D31BCNK were still (34±4) % (mean±SEM) and for IL‐12α Q57BCNK (54±6) % (mean±SEM) of those observed for the wild‐type (wt) protein (Figure 1 C).

Figure 1.

Noncanonical amino acid incorporation into IL‐12 in mammalian cells. A) Top: Schematic representation of the IL‐12α secondary structure (SS=signal sequence, red=α‐helices, mauve=loops, hexagons=predicted glycosylation sites, 10 aas=10 amino acids). Positions of amber codons (D31 and Q57) are indicated. Bottom: PDB structure of heterodimeric IL‐12 (PDB ID: 3HMX. Missing residues were modeled); N and C termini are indicated for IL‐12α. The positions selected for UAA incorporation into IL‐12α are marked with dashed circles. B) Unnatural amino acids (UAAs) and fluorophores used in this study. C) Top: Immunoblots of HEK‐293T cells expressing the BCNKRS/PylT pair and IL‐12αD31TAG or IL‐12αQ57TAG (abbreviated as D31* or Q57*, respectively) in the presence of BCNK. Bottom: Expression of IL‐12α D31BCNK and IL‐12α Q57BCNK relative to wild‐type IL‐12α was quantified from N=6 (D31BCNK) or N=3 (Q57BCNK) immunoblots (mean±SEM), respectively. Samples were normalized for Hsc70 levels. D) IL‐12α D31BCNK was tested for assembly‐induced secretion upon co‐expression of IL‐12β. HEK293T cells were co‐transfected with the indicated constructs in the presence of BCNK and samples were analyzed by immunoblotting. An increase in molecular weight upon secretion can be attributed to modification of IL‐12α glycans in the Golgi and IL‐12β populates two different glycospecies.30 L=lysate, M=medium, wt=wild‐type control. E) As in (D) but for IL‐12α Q57BCNK.

On the basis of these findings, we next assessed wild‐type (wt)‐like behavior of the BCNK‐bearing IL‐12α variants in terms of ER quality control. IL‐12α is retained in cells in isolation and forms incorrect disulfide bonds. Only the co‐expression of IL‐12β induces correct folding.30 IL‐12α D31BCNK showed wt behavior and was retained in cells in isolation and only secreted efficiently upon co‐expression of IL‐12β, including modification of its glycan residues in the Golgi,30 thus implying that ERQC works properly on the modified protein (Figure 1 D). The same behavior was observed for IL‐12α Q57BCNK, thus corroborating the minimally invasive character of BCNK incorporation (Figure 1 E). By using interleukin‐responsive reporter cell lines we were furthermore able to show that IL‐12 containing BCNK was also biologically active, even when fluorophore was added, thus implying proper folding in the presence of BCNK and fluorophore (Figure S1 C).

Lastly, by extending our approach to IL‐23, another IL‐12 family member prominently involved in autoimmune reactions and tumor development,29, 35, 36 we found that BCNK could also be incorporated site‐specifically into this protein with preservation of normal ERQC31 and biological activity (Figure S1 D–G).

Rapid bio‐orthogonal fluorescence labeling of interleukin subunits

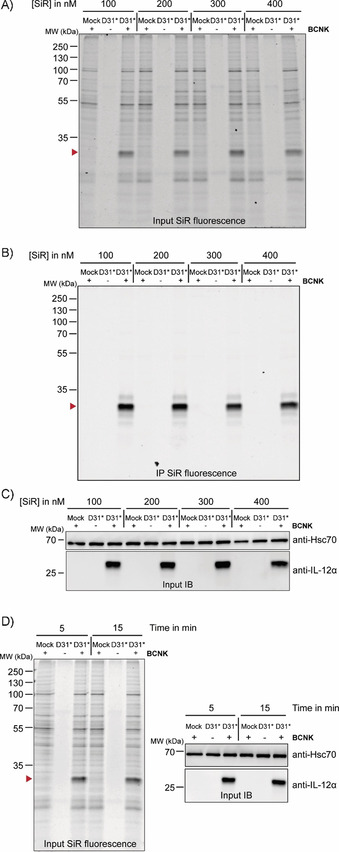

Having established efficient incorporation of BCNK into IL‐12α and IL‐23α with preservation of wt‐like behavior, we proceeded to fluorescent labeling of BCNK‐modified proteins. We focused on IL‐12α for a detailed characterization. Our first goal was to establish optimal labeling conditions. By using either tetramethylrhodamine‐tetrazine (TAMRA‐tetrazine, Figure S2A–F) or silicon rhodamine‐tetrazine (SiR‐tetrazine, Figure 2 A–D) we could efficiently label IL‐12α containing BCNK in living cells at fluorophore concentrations from 100–400 nm (Figure 2 A–C) even after as little as 5 min (Figure 2 D), with increasing labeling efficiencies being observed after longer labeling times in the case of TAMRA‐tetrazine (Figure S2D‐F) and very rapid labeling in that of SiR‐tetrazine (Figure S2, G and H).

Figure 2.

Bio‐orthogonal fluorescent labeling of BCNK‐modified IL‐12α is fast and efficient. A)–C) Cells expressing IL‐12α D31* constructs at 0.25 mm BCNK were treated with the indicated concentrations of SiR‐tetrazine fluorophore for 15 min and analyzed by A) in‐gel fluorescence of lysates (IL‐12α D31BCNK is marked with a red arrowhead), B) after immunoprecipitation (IP), and C) by immunoblotting (IB). The + and − lanes refer to the presence or absence of BCNK. SiR‐tetrazine fluorophore was present in all samples. D) Left: Representative gel for a reaction time course between 400 nm SiR‐tetrazine and IL‐12α D31BCNK analyzed by in‐gel fluorescence. Right: Cell lysates were additionally analyzed by immunoblotting.

Bio‐orthogonal fluorescence labeling allows protein turnover to be monitored

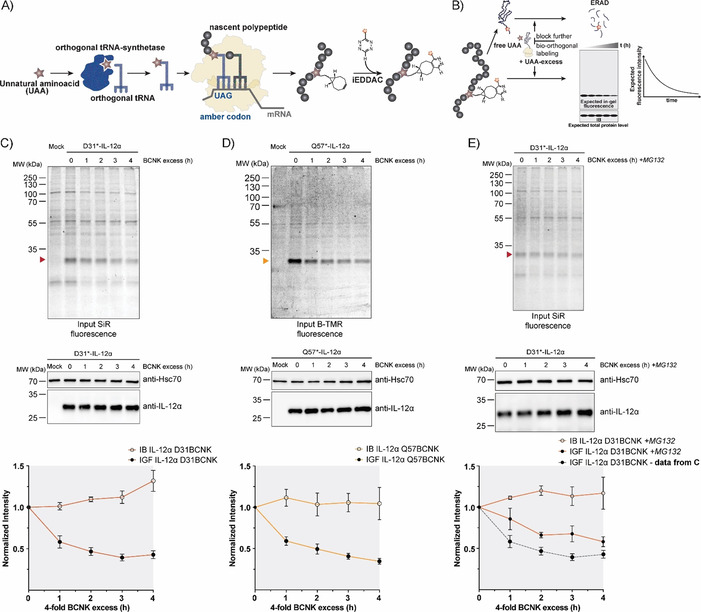

Taken together, these characteristics (wt‐like behavior combined with rapid and efficient labeling) provided us with an excellent tool with which to monitor protein turnover. To this end, we first labeled IL‐12α containing BCNK at position 31 or 57 with SiR‐tetrazine or BODIPY‐tetramethylrodamine‐tetrazine (B‐TMR‐tetrazine), respectively, for 15 min. Subsequently, we washed out the fluorophore and added an excess of free BCNK to quench all tetrazine fluorophore and at the same time maintain translation of the target protein IL‐12α. Hence, this approach should allow for observation of selective degradation of the fluorescently labeled protein pool without disturbing global translation in the cell (schematic in Figure 3 A, B). Because an UAA was used instead of radioactive amino acids to follow protein degradation in classical pulse‐chase experiments, we termed this approach uChase. As expected, we observed decreasing IL‐12α fluorescence for D31BCNK and Q57BCNK in uChase experiments (Figure 3 C, D top). Notably, this analysis was based on whole‐cell lysates, and thus does not depend on any downstream enrichment steps and also works for interleukins as proteins expressed at low levels (Figure S3 A–D). Furthermore, the assay was compatible with use either of SiR‐tetrazine (Figure 3 C) or of B‐TMR‐tetrazine (Figure 3 D) as fluorophore‐tetrazine conjugates to label IL‐12α. Starting from steady‐state, immunoblots revealed that the overall level of IL‐12α essentially remained constant over the time of the chase, as initially hypothesized (Figure 3 C, D, middle). The slight increase in protein levels can likely be attributed to the necessary washing steps before labeling, which were performed in the absence of BCNK. This will deplete cells of BCNK during these steps and thus lead to degradation of a small amount of IL‐12α before the BCNK excess is added and translation from Amber codon‐containing transcripts can resume. Consistent with previous studies,30, 32 the half‐life for IL‐12α degradation determined by our new uChase assay was (2.5±0.3) h (with use of D31* and SiR) and (2.2±0.2) h (with use of Q57* and B‐TMR; Figure 3 C, D, bottom), thus showing that labeling position and choice of fluorophore did not significantly affect the outcome of our experiment. Furthermore, neither BCNK incorporation nor SiR labeling (Figure S4 A and B) significantly changed the half‐life of IL‐12α in cycloheximide (CHX) chases, underscoring the minimally invasive character of our approach and establishing uChase as a way to monitor protein degradation. Two assays were performed to confirm that our assay monitored ERAD. Degradation of IL‐12α in our uChase assay was mediated by the proteasome as expected for an ERAD substrate, because it could be inhibited by MG132 (Figure 3 E). As a further test we used a dominant negative mutant of the ERAD E3 ubiquitin ligase Hrd1 (Hrd1C[291]S).37 This mutant decelerated degradation of IL‐12α in CHX chases (Figure S4 C) and to a similar extent degradation of B‐TMR‐labeled IL‐12α Q57BCNK in uChase assays (Figure S4 D and E), thus further validating our assay as a tool with which to monitor ERAD.

Figure 3.

Protein turnover monitored by the uChase approach. A) Workflow of in cellulo bio‐orthogonal labeling. During translation, an in‐frame TAG stop codon is suppressed by an evolved orthogonal tRNA‐synthetase/tRNA pair carrying the UAA. Next, the UAA can be labeled chemoselectively with a suitable probe, such as a fluorophore. B) uChase as a tool for monitoring protein degradation. To monitor protein removal rates (e.g., through ERAD), free UAA is washed out before the labeling reaction. Then, cells are treated with an excess of free UAA for a desired time interval to block any further bio‐orthogonal labeling of newly synthesized proteins without altering the protein biogenesis machinery. The protein half‐life can be measured from intensity plots quantified from in‐gel fluorescence (IGF) intensities of cell lysates. Total protein levels, as measured by immunoblotting (IB), are expected to remain constant. C) Top: Time course of fluorescence decrease for labeled IL‐12α D31BCNK; 0.25 mm BCNK and 400 nm SiR‐tetrazine fluorophore (15 min labeling) were used, followed by incubation with a fourfold excess of BCNK for the indicated time points and analyzed by in‐gel fluorescence. Middle: Total protein levels of IL‐12α D31BCNK were analyzed by immunoblotting. Bottom: The graph shows quantifications from in‐gel fluorescence and immunoblotting data, N=5 (mean± SEM). The intensity of the 0 h time point was set to 1. IB: immunoblotting. IGF: in‐gel fluorescence. D) The same analyses as shown in (C), but for the IL‐12α Q57BCNK variant labeled with B‐TMR [N=4 (mean±SEM)]. E) IL‐12α D31BCNK degradation was inhibited by the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 and the effect was analyzed by use of the uChase assay as in (C), N=4 (mean±SEM). A dotted gray line (bottom panel) shows IGF data from (C), (bottom panel) as a reference.

To demonstrate a more general applicability of our approach we additionally analyzed IL‐23α L150BCNK. For this protein, degradation occurred with a half‐life of less than 2 h, and was again not significantly affected by incorporation of BCNK (Figure S4 F). When IL‐23α L150BCNK was labeled with B‐TMR, our uChase approach again yielded a half‐life similar to those determined by CHX chases31 (Figure S4 F and G), thus showing that our approach can also be extended to other proteins with more rapid cellular turnover.

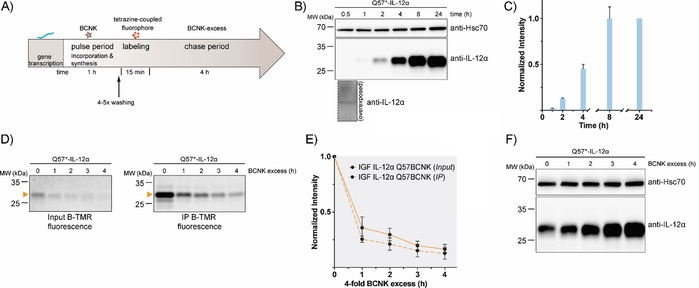

Development of a fluorescence‐based pulse‐chase assay

So far, our approach was similar to classical CHX chases because we started from a steady‐state pool of proteins, and then monitored their degradation, yet without globally inhibiting translation. Ideally, as possible with radioactive labeling10 and recently developed techniques for cytoplasmic proteins,13 one would like to label the protein of interest produced within a defined time interval, and then monitor its cellular fate. This, for example, would allow analysis of transport processes and post‐translational modifications such as changes in glycosylation with temporal resolution.38 To assess if such an approach (Figure 4 A) was in reach with our setup, we first analyzed how long BCNK needed to be added to cells in order for expression of IL‐12α Q57BCNK to be observed. Even after as little as 30 min we observed sufficient expression of IL‐12α Q57BCNK for detection by immunoblotting (Figure 4 B, C). Addition of BCNK for a 1 h pulse, labeling with B‐TMR for 15 min, and subsequent addition of a BCNK excess (chase) allowed us to monitor protein degradation of IL‐12α Q57BCNK produced within this 1 h time window (Figure 4 A, D, E).

Figure 4.

Establishment of a uChase‐based pulse‐chase assay. A) Illustration of a uPulse‐chase experiment. BCNK addition for a defined time interval (pulse period) allows protein synthesis from mRNA present to occur. After washing out of free BCNK and brief labeling with a tetrazine‐coupled fluorophore, a chase period follows (as described Figure 3 B). B) Representative immunoblots showing expression levels of IL‐12α Q57BCNK after different time intervals of the 0.25 mm BCNK pulse. An overexposure for the 30 min time point is shown below the blot. C) The graph shows a quantification from immunoblots; N=4 (mean±SEM). Samples were normalized for Hsc70 levels. The intensity of the 24 h time point was set to 1. d)–F) Following the schematic in (A), IL‐12α Q57BCNK degradation was followed by a uPulse‐chase experiment. D) Either whole‐cell lysates (Input, left) or immunoprecipitations to increase signal/noise (IP, right) are shown. E) Quantifications of (D); N=4 (mean±SEM). F) Immunoblots of IL‐12α Q57BCNK expression after different time points of the BCNK‐excess‐induced chase. The same samples as in (D), Input, were used, showing a decrease in the fluorescently labeled IL‐12α Q57BCNK pool and an increase in non‐labeled protein levels.

In these experiments, a half‐life of (1.1±0.1) h (from input samples) was observed for IL‐12α Q57BCNK. This might suggest that on a molecular level an IL‐12α pool produced within only a 1 h pulse period differs to some extent from the steady‐state pool. It should be noted that IL‐12α forms different redox species in cells, including homodimers.30 Their formation has not been kinetically analyzed yet but might impact degradation and give rise to this behavior. This further highlights the importance of pulse‐chase types of approaches. Because we were starting from a small pool of IL‐12α Q57BCNK (Figure 4 B, C), the decrease in the pool of fluorescently labeled protein (Figure 4 D, E) was accompanied by an increase in overall IL‐12α Q57BCNK levels during the 4 h chase. This is due to the fact that BCNK was present during the chase that allows for the synthesis of new, nonfluorescent IL‐12α Q57BCNK molecules (Figure 4 F). Taken together, these data show that a pulse‐chase approach is also possible with uChase, which opens up further future fluorescence‐based applications.

Conclusions

In this study, we have established a minimally invasive approach to monitor protein turnover in cells. To this end we incorporated the tetrazine‐reactive amino acid BCNK into different positions of the two human interleukins IL‐12 and IL‐23. BCNK incorporation was completely compatible with wt‐like folding, assembly, cellular quality control, and function of the interleukins. These characteristics allowed us to establish uChase as a new assay for monitoring protein degradation in mammalian cells. Our approach does not depend on any tag or other significant modifications of the protein of interest. It is furthermore compatible with different proteins even at very low expression levels, allows rapid degradation processes to be monitored, and does not depend on any downstream enrichment processes (e.g., immunoprecipitation, in which a specific antibody is needed). Furthermore, no global inhibition of translation is needed as in CHX chases; this can have pleiotropic effects and lead, for example, to the unwanted degradation of ERAD factors relevant for the protein under scrutiny. It should be noted that due to the low expression levels of interleukins, background labeling is present; for proteins expressed at higher levels this was mostly absent (Figure S3). Although we monitor protein turnover through in‐gel fluorescence, we envision that our approach might be amenable to future microscopy/FACS‐based live‐cell assays to monitor protein degradation directly in living cells when expression is sufficiently high. This would be a major advantage over currently available approaches. Use of overexpressed proteins, however, of course always comes with the caveat of possibly altered turnover if important factors become limiting. We show that the technique we have established also provides the basis for more complex fluorescence‐based pulse‐chase assays. Furthermore, because we were able to confirm receptor binding of our modified interleukins, fluorescently modified interleukins might provide a valuable tool for assessing the characteristics of their receptor engagement and/or to include other chemically reactive probes to modulate their functions selectively and thus go beyond being a tool for measuring protein turnover.

Experimental Section

See the Supporting Information for details on the materials and experimental procedures used, synthesis of small‐molecule compounds, and additional figures.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Y.G.M. gratefully acknowledges funding from a DAAD PhD scholarship. K.L. and M.J.F. are Rudolf Mößbauer Tenure Track Professors and as such gratefully acknowledge funding through the Marie Curie COFUND program and the Technical University of Munich Institute for Advanced Study, funded by the German Excellence Initiative and the European Union Seventh Framework Program under Grant Agreement 291 763. This work was performed within the framework of SFB 1035 (German Research Foundation DFG, Sonderforschungsbereich 1035, projects B10 and B11).

Y. G. Mideksa, M. Fottner, S. Braus, C. A. M. Weiß, T.-A. Nguyen, S. Meier, K. Lang, M. J. Feige, ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 1861.

References

- 1. Fersht A. R., Daggett V., Cell 2002, 108, 573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hartl F. U., Hayer-Hartl M., Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009, 16, 574–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Luheshi L. M., Crowther D. C., Dobson C. M., Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008, 12, 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adams B. M., Oster M. E., Hebert D. N., Protein J. 2019, 38, 317–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ellgaard L., McCaul N., Chatsisvili A., Braakman I., Traffic 2016, 17, 615–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braakman I., Bulleid N. J., Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011, 80, 71–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vembar S. S., Brodsky J. L., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 944–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith M. H., Ploegh H. L., Weissman J. S., Science 2011, 334, 1086–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guerriero C. J., Brodsky J. L., Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 537–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Simon E., Kornitzer D., Methods Enzymol. 2014, 536, 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khmelinskii A., Meurer M., Ho C. T., Besenbeck B., Fuller J., Lemberg M. K., Bukau B., Mogk A., Knop M., Mol. Biol. Cell 2016, 27, 360–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alber A. B., Paquet E. R., Biserni M., Naef F., Suter D. M., Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 1079–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schneider N., Gabelein C., Wiener J., Georgiev T., Gobet N., Weber W., Meier M., ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 3049–3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mayer S., Lang K., Synthesis 2017, 49, 830–848. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oliveira B. L., Guo Z., Bernardes G. J. L., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4895–4950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lang K., Davis L., Wallace S., Mahesh M., Cox D. J., Blackman M. L., Fox J. M., Chin J. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 10317–10320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Plass T., Milles S., Koehler C., Szymanski J., Mueller R., Wiessler M., Schultz C., Lemke E. A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 4166–4170; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 4242–4246. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Borrmann A., Milles S., Plass T., Dommerholt J., Verkade J. M., Wiessler M., Schultz C., van Hest J. C., van Delft F. L., Lemke E. A., ChemBioChem 2012, 13, 2094–2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nikic I., Plass T., Schraidt O., Szymanski J., Briggs J. A., Schultz C., Lemke E. A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 2245–2249; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 2278–2282. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Uttamapinant C., Howe J. D., Lang K., Beranek V., Davis L., Mahesh M., Barry N. P., Chin J. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4602–4605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aloush N., Schvartz T., Konig A. I., Cohen S., Brozgol E., Tam B., Nachmias D., Ben-David O., Garini Y., Elia N., Arbely E., Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schvartz T., Aloush N., Goliand I., Segal I., Nachmias D., Arbely E., Elia N., Mol. Biol. Cell 2017, 28, 2747–2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Serfling R., Seidel L., Bock A., Lohse M. J., Annibale P., Coin I., ACS Chem. Biol. 2019, 14, 1141–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsai Y. H., Essig S., James J. R., Lang K., Chin J. W., Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 554–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dieterich D. C., Link A. J., Graumann J., Tirrell D. A., Schuman E. M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 9482–9487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wu P., Lu M.-X., Cui X.-t., Yang H.-Q., Yu S.-l., Zhu J.-b., Sun X.-l., Lu B., Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2016, 37, 1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fierro-Monti I., Racle J., Hernandez C., Waridel P., Hatzimanikatis V., Quadroni M., PLoS One 2013, 8, e80423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vignali D. A., Kuchroo V. K., Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 722–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tait Wojno E. D., Hunter C. A., Stumhofer J. S., Immunity 2019, 50, 851–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reitberger S., Haimerl P., Aschenbrenner I., Esser von Bieren J., Feige M. J., J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 8073–8081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Meier S., Bohnacker S., Klose C. J., Lopez A., Choe C. A., Schmid P. W. N., Bloemeke N., Ruhrnossl F., Haslbeck M., Bieren J. E., Sattler M., Huang P. S., Feige M. J., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jalah R., Rosati M., Ganneru B., Pilkington G. R., Valentin A., Kulkarni V., Bergamaschi C., Chowdhury B., Zhang G. M., Beach R. K., Alicea C., Broderick K. E., Sardesai N. Y., Pavlakis G. N., Felber B. K., J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 6763–6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mayer S. V., Murnauer A., von Wrisberg M.-K., Jokisch M.-L., Lang K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 15876–15882; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 16023–16029. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yoon C., Johnston S. C., Tang J., Stahl M., Tobin J. F., Somers W. S., EMBO J. 2000, 19, 3530–3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oppmann B., Lesley R., Blom B., Timans J. C., Xu Y., Hunte B., Vega F., Yu N., Wang J., Singh K., Zonin F., Vaisberg E., Churakova T., Liu M., Gorman D., Wagner J., Zurawski S., Liu Y., Abrams J. S., Moore K. W., Rennick D., de Waal-Malefyt R., Hannum C., Bazan J. F., Kastelein R. A., Immunity 2000, 13, 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lupardus P. J., Garcia K. C., J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 382, 931–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nadav E., Shmueli A., Barr H., Gonen H., Ciechanover A., Reiss Y., Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 303, 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Braakman I., Lamriben L., van Zadelhoff G., Hebert D. N., Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. 2017, 90, 141.1–14.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary