Abstract

Older adults with cancer have increasing needs in physical, cognitive, and emotional domains, and they can experience decline in all domains with the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Social support plays a key role in supporting these patients, mitigating negative effects of diagnosis and treatment of cancer, and improving cancer outcomes. We review the importance of social support in older adults with cancer, describe the different components of social support and how they are measured, discuss current interventions that are available to improve social support in older adults, and describe burdens on caregivers. We also highlight Dr. Arti Hurria’s contributions to recognizing the integral role of social support to caring for older adults with cancer.

1. Introduction

Social support, as defined by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), is a network of family, friends, neighbors, and community members that is available in times of need to provide psychological, physical, and financial help to patients with cancer [1]. Studies have demonstrated that social support has a direct impact on the physical health, emotional adjustment, well-being, and overall survival of patients with cancer [2,3]. Patients with high levels of social support and social connectedness (presence of social ties without support exchange) have improved health and decreased mortality while those who lack social support and social connectedness have inferior oncologic outcomes such as increased prevalence of cancer progression and decreased overall survival [4–8].

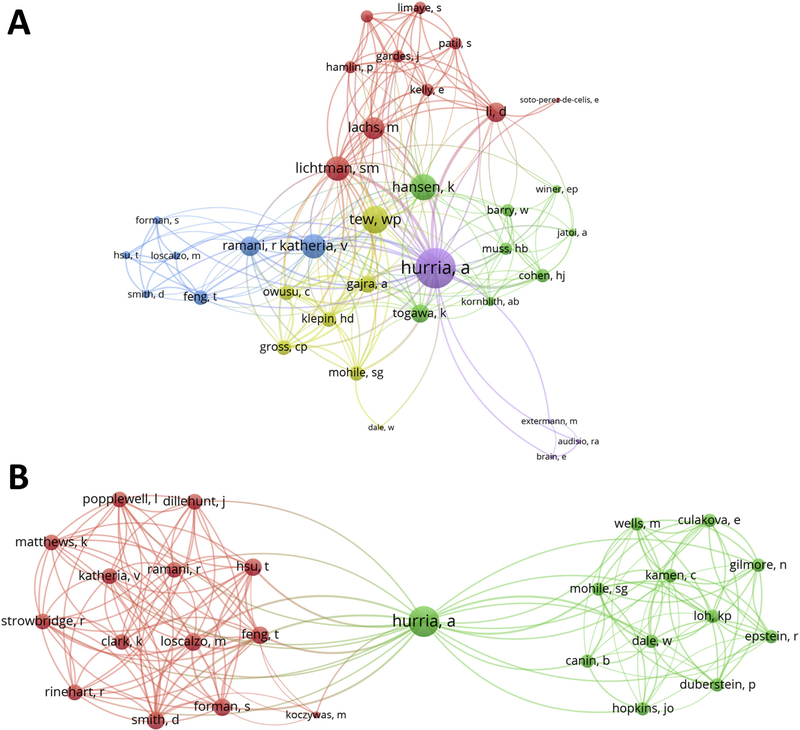

Older adults account for >62% of cancer survivors and represent a growing population with unique psychosocial needs [9,10]. Dr. Arti Hurria recognized the importance of social support in the care of older adults with cancer and incorporated social support measurements into a cancer-specific geriatric assessment (GA). Her work on the topic focused not only on measuring social support of older adults with cancer, but also on understanding its relationship to outcomes. Throughout her career, Dr. Hurria extensively collaborated with national and international researchers to study social support and caregiving in geriatric oncology, creating a new body of literature [11–13]. These collaborations led to the development of a multidisciplinary and multi-institutional network of investigators, which is represented in Fig. 1 utilizing bibliometric analyses.

Fig. 1.

Dr. Arti Hurria’s social support and caregivers research bibliometric network. A: Dr. Hurria’s Bibliometric Network on social support* Panel B: Bibliometric Network of work done by Dr. Hurria on caregivers** Each color represents a “cluster” of authors who worked on common papers. *Articles by Dr. Hurria with the terms “social” and “support” in the title and/or abstract obtained from PubMed Central database (22 documents). **Articles by Dr. Hurria mentioning the terms “caregivers” in the title and/or abstract obtained from PubMed Central database (9 documents). Authors with two or more co-authorships have been included. Created using VOSviewer (http://www.vosviewer.com/).

In this review, we describe social support needs of older adults with cancer and its protective effects, discuss the relationship between social support and outcomes, describe how to measure social support, list unmet social support needs in older adults with cancer, describe interventions that have been explored to improve social support in older adults and patients with cancer and discuss the important role of caregivers in providing social support. We also highlight the contributions to the field made by Dr. Hurria and her network of collaborators.

2. Older Adults With Cancer and their Need for Social Support

A diagnosis of cancer may lead to physical and emotional stress regardless of age; however, the unique needs of older adults compound the stresses resulting from a cancer diagnosis. Compared to their younger counterparts, older adults have more pre-existing chronic diseases, impaired physical and cognitive function, and decreased physiologic reserve, making the physical and emotional demands of cancer and cancer treatment more difficult [14]. Older adults with cancer are especially vulnerable to short- and long-term treatment toxicities [15,16]. As a result, older adults with cancer are more likely to require assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs; such as bathing, dressing and toileting) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs; such as doing housework, taking transportation and making phone calls) [17]. Following a cancer diagnosis, older adults with cancer are more likely to experience depressive symptoms and anxiety as well as reduced quality of life (QOL) [18]. The presence of distress in older adults with cancer is common and can be associated with worse function. Dr. Hurria and colleagues identified significant distress (defined as a distress score ≥ 4 using the Distress Thermometer) in 41% of patients [19]. Increased distress scores were significantly associated with needing increased assistance with IADLs and lower Medical Outcomes Survey (MOS) physical function score. These negative effects can persist long after cancer treatment is completed, and older adults continue to report high distress, depression, anxiety, and poor QOL [20,21].

With advancing age, older adults experience a reduction of their social support structure due to life events, such as widowhood and retirement. This in turn leads to isolation and loneliness, which may exacerbate their emotional response to cancer. Combined, these biopsychosocial factors can limit an older adult’s ability to cope with and manage their disease, and negatively impact QOL [22].

3. Protective Effects of Social Support

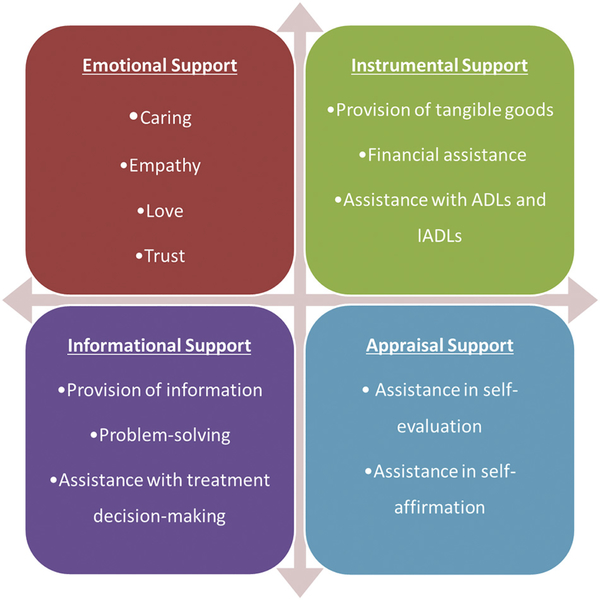

Adequate social support is necessary for older adults to navigate sudden life changes and emotional responses associated with cancer from diagnosis through survivorship. Broadly speaking, social support is composed of four defining attributes: emotional, instrumental, informational, and appraisal support (Fig. 2) [23]. All of these attributes of social support interact in order to protect the supported person, and each may exert unique beneficial effects.

Fig. 2.

Attributes of social support.

Several theoretical frameworks have been postulated to explain the multidimensional effects social support has on the well-being and health of older adults; the two most widely accepted are the buffering hypothesis and direct effect model. The buffering hypothesis suggests that support reduces harms from stressful events by preventing the individual from appraising a situation as threatening or demanding [24]. In contrast, the direct effect model suggests that social support is beneficial regardless of the amount of stress perceived by the individual [25]. In this model, the perception that others are willing to help increases self-esteem and provides the individual with a sense of control over their situation. Furthermore, belonging to a social network could impact treatment outcomes directly by positively influencing treatment adherence and illness-management behaviors [26]. An individual’s social circle is critical to participation in and optimization of all aspects of cancer treatment including symptom management, care coordination, assistance with ADLs and IADLs, and emotional support.

4. Association of Social Support With Patient Outcomes

The benefits of social support on survival and physical and emotional health have been studied in older adults as well as patients with cancer. In a meta-analysis of 87 studies in the general geriatric population, higher levels of perceived social support, a larger social network, and being married were associated with decreased mortality risk [7]. Higher levels of perceived social support were also associated with better mental health outcomes and improved QOL in older adults [27].

Studies on the effects of social support on oncologic outcomes in older adults with cancer are mixed. Earlier studies demonstrated that social support is associated with survival and that unmarried patients, those living alone or those lacking in emotional connectedness to others have an increased risk of having metastatic disease at diagnosis, are more likely to be undertreated and have poorer survival [28–30]. In a secondary analysis of a cooperative group study of older patients with breast cancer from the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 49907/Alliance A171301, Dr. Hurria and colleagues found a trend towards improved survival among patients who were living with someone and/or were married [13]. However, this finding was non-significant in multivariate analysis. The authors hypothesed that this may be because patients included in clinical trials may have a greater degree of baseline social support and better functional status, hence the effects of social support and survival was not demonstrated. There was no association between social support and treatment completion or development of serious adverse events.

Inadequate social support may also affect QOL and psychological state in older adults with cancer, as shown by Dr. Hurria and colleagues in several studies [11,31,32]. In a secondary analysis of the CALGB/Alliance 369901 cooperative group study of 1280 older adults with nonmetastatic breast cancer, women with higher tangible social support (i.e., having someone to take them to the doctor if needed) were less likely to experience a steep decline in health-related QOL (HRQOL) [11]. In a cross-sectional study of 1457 older adults with cancer, having emotional needs (i.e., needing someone to listen when needing to talk) and physical support needs (i.e., needing someone to help when fatigued) were also strongly associated with HRQOL [31]. Inadequate social support has also been shown by Dr. Hurria and the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) to be associated with depression [32].

Social support may also affect the tolerance of older adults with cancer to cancer therapy. In a prospective study of 500 older adults starting a new line of chemotherapy, Dr. Hurria and CARG developed a risk model to predict chemotoxicity (www.mycarg.org/tools) [33,34]. In addition to patient, tumor and treatment variables, several geriatric assessment variables including decreased social activity due to physical health or emotional problems, were found to be predictive of an increased risk of chemotherapy toxicity.

5. How Social Support Affects Outcomes Through Physiological and Biological Mediators

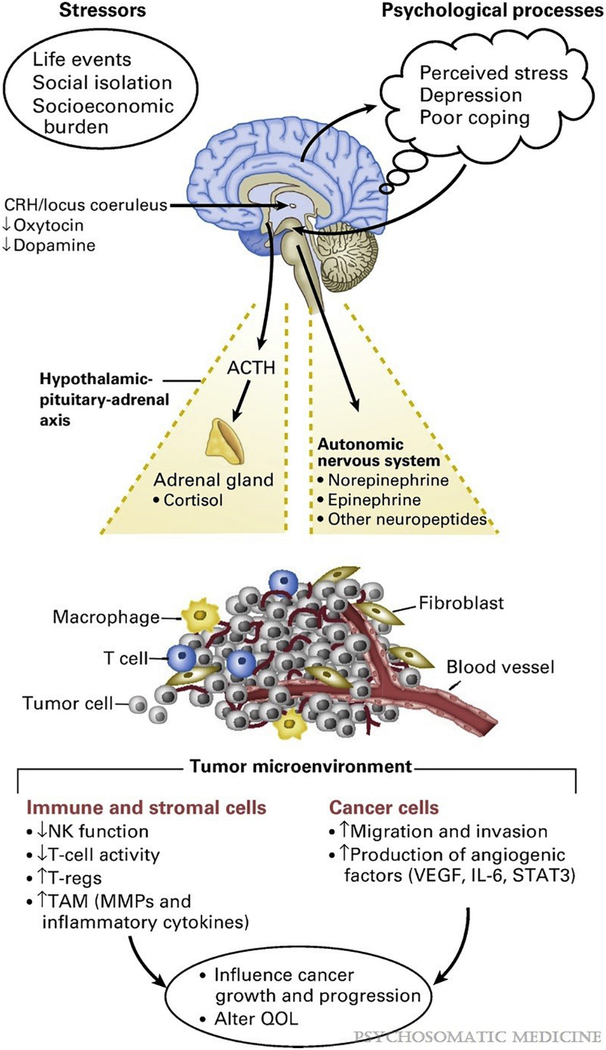

Social stress caused by isolation, social relationship deficits, and a lack of social support have been linked to increased biomarkers of inflammation, immune system impairment, tumor growth, and metastases [6,35,36]. Molecular studies suggest that adrenergic receptor activation is the primary pathway linking stress exposure to tumor growth and progression of disease [37]. Social stress can trigger a stress response that activates the autonomic nervous system, sympathetic nervous system, and the hypothalamus-pituitary-axis. This results in the release of cortisol, catecholamines, and neuropeptides, all of which alter gene expression to promote inflammation in the tumor microenvironment and ultimately leads to tumor growth and disease progression (Fig. 3) [38,39].

Fig. 3.

Effects of social stress on tumor microenvironment, cancer growth and progression. Used with permission from Lutgendorf et al. [46].

In patients with cancer, social stress has been associated with increased inflammatory cytokines such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) that mediate cancer proliferation and metastasis and have been associated with poor survival [40–42]. Conversely, social support has been associated with an increase in anti-tumor immune cells as well as a decrease in inflammatory cytokines [6]. Patients with ovarian cancer who had higher levels of social support were found to have higher levels of natural killer (NK) cells, which inhibit tumor growth, in the tumor microenvironment and the peripheral blood [43]. Higher levels of social well-being has been associated with decreased levels of metalloproteinases (MMPs) which promote cancer growth and decreased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, VEGF, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α [8,44]. In women with breast cancer, greater satisfaction with social resources was associated with less leukocyte pro-inflammatory (i.e. cytokines) and pro-metastatic (i.e. matrix metalloproteinases) gene expression on microarray analysis [45]. These studies suggest that social support, by acting as a buffer against stress, may exert an immunoprotective effect and thus favorably impact cancer outcomes.

6. Measuring Social Support in Older Adults With Cancer

When assessing social support, a distinction between perceived and received support should be made. Perceived social support refers to the subjective evaluation of the availability and adequacy of social connections, while received social support focuses on the quantity and the quality of the actual provided help [47,48]. This distinction is essential because different methods are used to assess each type of support, and each type of support exerts differential effects on health and well-being [47]. That being said, both are closely related to the characteristics of each individual’s social network, which is the set of linkages and personal contacts through which each person maintains his/her social identity and receives support [49]. Social networks are complex systems which have specific structural, functional, and interactional characteristics that define them and make them unique, including their directionality, geographic dispersion, density, and homogeneity (Table 1) [50,51].

Table 1.

Characteristics of social networks.

Adapted from Heaney et al. [51].

| Construct | Definition |

|---|---|

| Directionality | Extent to which members share equal power and influence (power dynamics between patient/caregiver) |

| Geographic dispersion | Extent to which the network’s members live in close proximity to the patient |

| Density | Extent to which network members know and interact with each other |

| Homogeneity | Extent to which network members are demographically similar (in age, race/ethnicity, marital status, etc.) |

The complicated nature and multiple dimensions of social support make measuring it extremely difficult. This is further complicated by the fact that perceptions regarding the quality or quantity of social support may vary across geographic, social, economic, racial, and ethnic groups [52]. Therefore, the effect of social support on psychological and biological stress response may vary by group being studied. In order to adequately measure social support, instruments should comprise a combination of several items, including an assessment of the structure of social networks, the availability of support (including the number of persons who can provide it), the role of each supporting individual, and perceptions regarding the quality of the support [25]. There are several validated tools to measure social support including the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS), Duke-University of North Carolina Functional Social Support Questionnaire (DUFSS), and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support Scale (MPSSS) [53–55].

The MOS-SSS was developed as part of a two-year study, which included patients with chronic conditions, and was designed to develop practical tools for the routine monitoring of patient outcomes in medical practice [54]. The original development of the MOS-SSS was carried out among a subsample of 2987 patients and included four subscales (emotional/informational, tangible, affectionate, and positive social interaction) [56]. The survey measures perceived support, and is made up of 19 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale from “none of the time” to “all of the time.”

Two of the MOS-SSS subscales (emotional/informational and tangible support) were studied and incorporated into what is now the CARG cancer-specific geriatric assessment by Dr. Hurria [57]. Twelve of the 19 MOS-SSS items are included in the assessment. It had excellent internal consistency among older adults with cancer, with a standardized Cronbach alpha of 0.95, and high test-retest reliability (Spearman coefficient 0.86) [58]. The MOS-SSS was effective in identifying social support needs in older adults with cancer [59]. Its use in a brief self-reported questionnaire in older adults with cancer resulted in a referral to social work for 45% of patients.

7. Unmet Social Support Needs in Older Adults

Because older adults experience an increase in needs and a decrease in social network as they age, they are more likely to have unmet social support needs. In the setting of cancer, however, very limited data exist in understanding unmet social support needs among older adults.

Specific social support needs of 1460 older US adults with mixed cancer types were recently evaluated in a study utilizing the MOS-SSS [60]. Social support was categorized into five domains: physical, emotional, informational, practical, and medical support. Among these patients, two-thirds had at least one social support need and 45% had at least one need that was unmet. Unmet need was highest in medical support (39%), followed by informational (35%), physical (30%), emotional (28%), and practical (20%) support. Common unmet needs included not having someone to share worries with, not having help if patient was fatigued, and not having help with daily chores when sick (8% in each). Those who had an increasing number of unmet social support needs were more likely to have lower QOL. Several subgroups were more likely to have unmet needs in one or more social support domains. These included minority patients and those who were not married, had lower household income, and had higher symptom burden. More research is needed to understand why certain subgroups are more likely to have unmet social support needs so that interventions can be specifically designed for these patients.

8. Social Support Interventions

Much of Dr. Hurria and her colleagues’ work on social support in older adults with cancer were aimed at identifying patients lacking in social support so that interventions could be implemented to mitigate its negative effects. However, there has been little research on social support interventions in older adults with cancer.

Several different interventions have been investigated in the older adult population without cancer, with the majority of these aimed at reducing social isolation and promoting social connectedness in older adults [61,62]. Social interactions can be facilitated through group activities, such as engaging in shared interests and day care centers, or can be one-on-one, such as engaging individually with volunteers who are able to provide a new friendship to a lonely individual [57]. These interventions can take place in person, via telephone, or using technology-based videoconferencing and social networking. Animal-assisted therapy involving felines or canines has been used to alleviate loneliness in older adults. All of these interventions have been successful in reducing loneliness, promoting happiness, and life satisfaction in older patients without cancer [61]. Solitary interventions such as videoconferencing or solitary pet therapy are equally effective as group interventions in reducing loneliness, suggesting that effective social support interventions can be offered even to those older adults who may be housebound or unable to easily participate in group activities.

In patients with cancer, studies examining the effects of interventions targeting social isolation are limited and have either demonstrated small or no effects of reducing loneliness. Two studies that provided 13 months of telephone social support as well as educational information to patients with cancer found significant but very small differences in loneliness scores [63,64]. In a study of 42 patients with head and neck cancer who were starting multimodal concurrent chemoradiation, animal-assisted therapy consisting of a visit from a certified therapy dog team at each treatment visit increased social well-being and emotional well-being scores [65].

Patient navigation programs which involve individualized assistance by cancer survivors, nurses, social workers and other health workers to patients with cancer have also been developed. These programs were initially developed to advocate for minority and low-income patients with breast cancer in a medically underserved urban community but now have widespread use [66]. The patient navigator is viewed as a proactive patient representative distinct from the social worker, who focuses on the concrete needs of the patient and guide the patient from cancer diagnosis through treatment. Patients in a patient navigation intervention program, Breast CARES (Cancer, Advocacy, Resource Education and Support), reported that it helped them overcome financial barriers (73%), transportation needs (60%), improved communication with medical providers (73%) and helped them access additional support (i.e. support groups) [67]. Although patient navigation improves emotional well-being and patient self-efficacy, the few studies that have evaluated its effect on social well-being found no significant effects [67,69].

Peer support, which is support from a cancer patient or survivor, may help to compensate for unmet social support needs of patients with cancer and help them cope with the illness. Patients with cancer are more likely to participate in peer support groups when they feel their family and friends do not understand their cancer experience [70,71]. Through mutual identification and shared experiences, peers can provide experiential empathy, as well as emotional, informational and appraisal support for patients with cancer [72]. In patients with cancer, peer support interventions increase perceived social support and sense of belonging and improve psychosocial outcomes by providing both informational and emotional support [73]. Peer discussion groups were particularly helpful for women who lacked social support compared to those who reported adequate social support [74]. Conversely a small number of studies have also found that patients who reported adequate social support and peer counselors were negatively impacted by peer group interventions with decreased physical function outcomes, dissatisfaction with the medical team and increased emotional suppression [69,74]. A meta-analysis of peer-led interventions for patients with cancer found that effects on social support, emotional health, coping, and quality of life were stronger interventions when delivered face-to-face (versus on the telephone) and when peers had counseling experience [75]. This suggests that patients must be carefully selected for peer support interventions and patient counselors carefully trained and supervised to facilitate them.

Internet based peer-support programs and social media platforms may increase social support in patients with cancer who may not have access to face-to-face peer support or patient navigation. Both allow patients to create social networks to exchange information and personal stories regarding their illness and get social support from their peers [76]. A 5-month, home-based computer intervention for women aged ≤60 years with breast cancer that included informational content, discussion groups, decision support and answers from cancer experts on found improvements in patient-reported emotional and instrumental social support compared to controls [77]. Other studies of online peer-support group interventions, conducted mostly in patients with breast cancer, have not shown a clear benefit in social support, psychosocial measures or QOL [78,79]. However, these studies were small and of low quality.

Social media platforms (i.e. blogs, Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook) are different from internet-based support groups in that they are they offer user-friendly interfaces, easy access, fast communication and actively engage users [80]. However, compared to internet-based support groups created by and maintained by health professionals, social media platforms are largely not curated or moderated by experts and can contain negative information [81]. Harassment of participants has also been an issue compared to internet-based support groups generated by health professionals. Studies of social media interventions in patients with cancer are limited but have been shown to be feasible [80]. Attai et al. found that patients who participated in a Twitter support community for patients with breast cancer (Breast Cancer Social Media tweet chat #BCSM) reported increased knowledge and decreased anxiety with 67% of patients who initially reported “high/extreme” anxiety reporting “low/no” anxiety after participation. Effects of the intervention on social support was not evaluated.

Many of these interventions could also help meet unmet social support needs in older adults with cancer. In a study of older adults with advanced stage cancer, telephone monitoring significantly decreased anxiety, depression and overall distress compared to provision of educational material alone [82]. Patient navigators may be of particular use to frail or vulnerable older adults to help them navigate complex decision making and treatment and provide tangible support such as transportation to the hospital and provision of healthy meals. Videoconferencing, internet-based and social media interventions may be beneficial for older adults who are unable to access in-person support groups due to geographic, transportation or physical mobility constraints. Comfort and competency with the internet, however, are important considerations when considering the utility of these types of interventions. A 2012 Pew Research Center report found that 53% of Americans aged ≥65 years use the internet or email, and 33% use social networks, both of which represented a significant growth from previous years but lower than younger adults [83]. Internet adoption among older adults ≥75 years remains low (34%). Older adults continue to have concerns over online privacy and many do not understand online social networks [84]. As a result, older adults may have difficulty with using technology and may have difficulty in accessing online resources. Studies are needed to determine if these interventions can be tailored to older adults with cancer.

9. Impact of Caregiving on Social Supports

Informal caregivers, typically family and friends, represent the main source of social support for patients. They are increasingly relied upon to provide support with cancer treatment and symptom management, medical and nursing tasks, ADLs, and IADLs [86]. While social support is critical in helping older adults with cancer through the stages of the cancer continuum, caregiving can have significant physical, emotional, and financial impacts on the caregivers. Older caregivers, the majority of whom are spouses, are usually older themselves with an average age of 63 and have similar vulnerabilities as those they care for [87]; 36% had fair/poor health or a serious health condition [88].

Caregiving can cause emotional distress, including depression and anxiety. The level of distress among caregivers is increased when the care recipients have poor functional status and increased symptom burden [89]. Greater emotional distress in-turn leads to increased caregiver burnout, fatigue, and sleep disturbance [90]. Concerningly, older caregivers who experience caregiver burden have an increased risk of mortality [91].

Dr. Hurria recognized the importance of caregiver health in the care of older adults with cancer. Among older adults with cancer seen in the ambulatory setting, Dr. Hurria’s team found that 75% of caregivers reported some burden and 15% reported high caregiver burden [12]. Employed caregivers and caregivers of patients who required help with IADLs were more likely to experience high caregiver burden. Caregivers noted greater IADL needs of patients compared to the patient’s own report and this difference in patient-caregiver assessment was also associated with an increased likelihood of high caregiver burden [92]. Another group also identified that caregivers of older patients who had a higher number of impairments on the geriatric assessment were more likely to experience depression and lower caregiver QOL [93].

In caregivers of hospitalized older adults with cancer, Dr. Hurria and colleagues found that caregivers have relatively good QOL [94]. Most caregivers (79%) reported excellent or good health and had no major comorbidities. However, 22% reported a decline in their health as a result of caregiving. Those with poorer mental health, less social support, and who cared for patients with poor function were more likely to experience poorer QOL. These results suggest that in addition to assessing the patient’s social support, understanding the caregiver’s social support may be necessary.

It is equally important to consider that older adults with cancer may themselves be caregivers and caregiving responsibilities may impact patient treatment decisions and health management [95,96]. Patients with cancer who are caregivers have been found to have poorer social outcomes and depressed mood [97,98]. For example, in a study of patients with colon cancer, a majority of whom were > 65 years of age, 20% stated that they had caregiver responsibilities [97]. These patients were found to have more social distress on the Social Difficulties Inventory (SDI-21) than patients without caregiver responsibilities, particularly in the financial and emotional subscales. Identifying patients with caregiver roles early is also necessary in order to provide them with adequate social support.

Dr. Hurria strongly advocated that the geriatric assessment should be utilized early in the management of older adults with cancer to identify those with increased needs and increased risk of treatment toxicity, both of which may affect patient and caregiver outcomes. Once identified, early mobilization of community resources to provide assistance and remove some of the burdens should be considered. By identifying those individuals at increased risk for negative outcomes and implementing early interventions, both patient and caregiver health and QOL may be improved.

10. Conclusion

Older adults with cancer have significant physical, emotional, informational, practical, and medical support needs. Dr. Hurria’s work has expanded the literature on the effects of social support on outcomes among older adults with cancer and the importance of identifying social support needs using the geriatric assessment. Existing interventions for social support are primarily tested in the general geriatric population and research is needed to understand if and how these translate to older adults with cancer and whether adaption is needed. To support a growing population of older adults with cancer, it is also imperative to recognize the burdens on caregivers and provide them with additional support.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

Sindhuja Kadambi: No conflict of interest.

Enrique Soto-Perez-de-Celis.

Luiz A. Gil-Jr: No conflict of interest.

Jessica Krok-Schoen.

Tullika Garg: No conflict of interest.

Gordon Taylor Moffat: No conflict of interest.

Nicolò Matteo Luca Battisti: Pfizer and Genomic Health.

Supriya Mohile: No conflict of interest.

Tina Hsu: Celgene, Apobiologix, Ipsen, and Genomic Health.

Manuscript Writing

Sindhuja Kadambi, Enrique Soto-Perez-de-Celis, Tullika Garg, Kah Poh Loh, Jessica L Krok-Schoen, Nicolò Matteo Luca Battisti, Gordon Taylor Moffat, Luiz A Gil-Jr, Tina Hsu.

Approval of Final Manuscript

Sindhuja Kadambi, Enrique Soto-Perez-de-Celis, Tullika Garg, Kah Poh Loh, Jessica L Krok-Schoen, Nicolò Matteo Luca Battisti, Gordon Taylor Moffat, Luiz A Gil-Jr, Supriya Mohile, Tina Hsu.

References

- [1].National Cancer Institute. NCI dictionary of cancer terms. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/social-support. (Accessed Online March 17, 2019).

- [2].Usta YY. Importance of social support in cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012;13(8):3569–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nausheen B, Gidron Y, Peveler R, Moss-Morris R. Social support and cancer progression: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2009;67(5):403–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yang YC, Li T, Ji Y. Impact of social integration on metabolic functions: evidence from a nationally representative longitudinal study of US older adults. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Penwell LM, Larkin KT. Social support and risk for cardiovascular disease and cancer: a qualitative review examining the role of inflammatory processes. Health Psychol Rev 2010;4(1):42–55. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Reiche EM, Nunes SO, Morimoto HK. Stress, depression, the immune system, and cancer. Lancet Oncol 2004;5(10):617–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2010;75(2):122–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Boen CE, Barrow DA, Bensen JT, et al. Social relationships, inflammation, and cancer survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prevent 2018;27(5):541–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69(1): 7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Stanton AL. What happens now? Psychosocial care for cancer survivors after medical treatment completion. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(11):1215–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dura-Ferrandis E, Mandelblatt JS, Clapp J, et al. Personality, coping, and social support as predictors of long-term quality-of-life trajectories in older breast cancer survivors: CALGB protocol 369901 (Alliance). Psychooncology 2017;26(11):1914–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hsu T, Loscalzo M, Ramani R, et al. Factors associated with high burden in caregivers of older adults with Cancer. Cancer 2014;120(18):2927–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jatoi A, Muss H, Allred JB, et al. Social support and its implications in older, early-stage breast cancer patients in CALGB 49907 (Alliance A171301). Psycho-oncology 2016;25(4):441–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rowland JH, Hewitt M, Yancik R. Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health, and disability. J Gerontol A 2003;58(1):M82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Puts MT, Papoutsis A, Springall E, Tourangeau AE. A systematic review of unmet needs of newly diagnosed older cancer patients undergoing active cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 2012;20(7):1377–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Shahrokni A, Wu AJ, Carter J, Lichtman SM. Long-term toxicity of cancer treatment in older patients. Clin Geriatr Med 2016;32(1):63–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].van Abbema D, van Vuuren A, van den Berkmortel F, et al. Functional status decline in older patients with breast and colorectal cancer after cancer treatment: a prospective cohort study. J Geriatr Oncol 2017;8(3):176–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jones SM, LaCroix AZ, Li W, et al. Depression and quality of life before and after breast cancer diagnosis in older women from the Women’s Health Initiative. J Cancer Surviv 2015;9(4):620–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hurria A, Li D, Hansen K, et al. Distress in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(26):4346–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Deimling GT, Brown SP, Albitz C, Burant CJ, Mallick N. The relative importance of cancer-related and general health worries and distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2017;26(2):182–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Krok-Schoen JL, Naughton MJ, Bernardo BM, Young GS, Paskett ED. Fear of recurrence among older breast, ovarian, endometrial, and colorectal cancer survivors: findings from the WHI LILAC study. Psychooncology 2018;27(7):1810–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Robb C, Lee A, Jacobsen P, Dobbin KK, Extermann M. Health and personal resources in older patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy. J Geriatr Oncol 2013;4(2): 166–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Langford CPH, Bowsher J, Maloney JP, Lillis PP. Social support: a conceptual analysis. J Adv Nurs 1997;25(1):95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. American Psychological Association; 1985; 310–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Raube K Health and social support of the elderly; 1992. (Doctoral dissertation) Retrieved from RAND Graduate School. (No. N-3467-RGSD). [Google Scholar]

- [26].Leslie RM, DiMatteo MR, Mary PG. Social networks, social support, and health-related behavior. In: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Applebaum AJ, Stein EM, Lord-Bessen J, Pessin H, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W. Optimism, social support, and mental health outcomes in patients with advanced cancer. Psycho-oncology 2014;23(3):299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31(31):3869–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cavalli-Bjorkman N, Qvortrup C, Sebjornsen S, et al. Lower treatment intensity and poorer survival in metastatic colorectal cancer patients who live alone. Br J Cancer 2012;107(1):189–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lutgendorf SK, De Geest K, Bender D, et al. Social influences on clinical outcomes of patients with ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(23):2885–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pisu M, Azuero A, Halilova KI, et al. Most impactful factors on the health-related quality of life of a geriatric population with cancer. Cancer 2018;124(3):596–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Weiss Wiesel TR, Nelson CJ, Tew WP, et al. The relationship between age, anxiety, and depression in older adults with cancer. Psycho-oncology 2015;24(6):712–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hurria A, Mohile S, Gajra A, et al. Validation of a prediction tool for chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(20):2366–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 2011;29(25): 3457–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yang YC, Schorpp K, Harris KM. Social support, social strain and inflammation: evidence from a national longitudinal study of U.S. adults. Soc Sci Med (1982) 2014; 107:124–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].McClintock MK, Conzen SD, Gehlert S, Masi C, Olopade F. Mammary cancer and social interactions: identifying multiple environments that regulate gene expression throughout the life span. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2005;60:32–41 Spec No 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Shin KJ, Lee YJ, Yang YR, et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying psychological stress and cancer. Curr Pharm Des 2016;22(16):2389–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tilan J, Kitlinska J. Sympathetic neurotransmitters and tumor angiogenesis-link between stress and cancer progression. J Oncol 2010;2010:539706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Seeman TE, Lusignolo TM, Albert M, Berkman L. Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Health Psychol 2001;20(4):243–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Nausheen B, Carr NJ, Peveler RC, et al. Relationship between loneliness and proangiogenic cytokines in newly diagnosed tumors of colon and rectum. Psychosom Med 2010;72(9):912–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Costanzo ES, Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK, Anderson B, Sorosky J, Lubaroff DM. Psychosocial factors and interleukin-6 among women with advanced ovarian Cancer. cancer 2005;104(2):305–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hughes S, Jaremka LM, Alfano CM, et al. Social support predicts inflammation, pain, and depressive symptoms: longitudinal relationships among breast cancer survivors. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014;42:38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lamkin DM, Lutgendorf SK, McGinn S, et al. Positive psychosocial factors and NKT cells in ovarian cancer patients. Brain Behav Immun 2008;22(1):65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lutgendorf SK, Johnsen EL, Cooper B, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and social support in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Cancer 2002;95(4):808–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Jutagir DR, Blomberg BB, Carver CS, et al. Social well-being is associated with less pro-inflammatory and pro-metastatic leukocyte gene expression in women after surgery for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;165(1):169–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK. Biobehavioral factors and cancer progression: physiological pathways and mechanisms. Psychosom Med 2011;73(9):724–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Heikkinen R-L, Lyyra T-M. Perceived social support and mortality in older people. J Gerontol B 2006;61(3):S147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Eagle DE, Hybels CF, Proeschold-Bell RJ. Perceived social support, received social support, and depression among clergy. J Soc Pers Relat 2018;0265407518776134. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Walker KN, MacBride A, Vachon MLS. Social support networks and the crisis of bereavement. Soc Sci Med (1967) 1977;11(1):35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 4th ed.. San Francisco, CA, US: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education : Theory, research, and practice.. 4th ed.San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Taylor SE, Welch WT, Kim HS, Sherman DK. Cultural differences in the impact of social support on psychological and biological stress responses. Psychol Sci 2007;18 (9):831–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, de Gruy FV, Kaplan BH. The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire. Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care 1988;26(7):709–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Tarlov AR, Ware JE Jr, Greenfield S, Nelson EC, Perrin E, Zubkoff M. The medical outcomes study: an application of methods for monitoring the results of medical care. JAMA 1989;262(7):925–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess 1988;52(1):30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 1991;32(6): 705–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Hurria A, Gupta S, Zauderer M, et al. Developing a cancer-specific geriatric assessment: a feasibility study. Cancer 2005;104(9):1998–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hurria A, Akiba C, Kim J, et al. Reliability, validity, and feasibility of a computer-based geriatric assessment for older adults with Cancer. J Oncol Pract 2016;12(12): e1025–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Hurria A, Lichtman SM, Gardes J, et al. Identifying vulnerable older adults with cancer: integrating geriatric assessment into oncology practice. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55(10):1604–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Williams GR, Pisu M, Rocque GB, et al. Unmet social support needs among older adults with cancer. Cancer 2019;125(3):473–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Gardiner C, Geldenhuys G, Gott M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: an integrative review. Health Soc Care Community 2018; 26(2):147–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].O’Rourke HM, Collins L, Sidani S. Interventions to address social connectedness and loneliness for older adults: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr 2018;18(1):214–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Fukui S, Koike M, Ooba A, Uchitomi Y. The effect of a psychosocial group intervention on loneliness and social support for Japanese women with primary breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2003;30(5):823–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Coleman EA, Tulman L, Samarel N, et al. The effect of telephone social support and education on adaptation to breast cancer during the year following diagnosis. Oncol Nurs Forum 2005;32(4):822–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Fleishman SB, Homel P, Chen MR, et al. Beneficial effects of animal-assisted visits on quality of life during multimodal radiation-chemotherapy regimens. J Commun Support Oncol 2015;13(1):22–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Oluwole SF, Ali AO, Adu A, et al. Impact of a cancer screening program on breast cancer stage at diagnosis in a medically underserved urban community. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196(2):180–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Madore S, Kilbourn K, Valverde P, Borrayo E, Raich P. Feasibility of a psychosocial and patient navigation intervention to improve access to treatment among underserved breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2014;22(8):2085–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Giese-Davis J, Bliss-Isberg C, Carson K, et al. The effect of peer counseling on quality of life following diagnosis of breast cancer: an observational study. Psychooncology 2006;15(11):1014–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Taylor SE, Falke RL, Shoptaw SJ, Lichtman RR. Social support, support groups, and the cancer patient. J Consult Clin Psychol 1986;54(5):608–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Shaw BR, McTavish F, Hawkins R, Gustafson DH, Pingree S. Experiences of women with breast cancer: exchanging social support over the CHESS computer network. J Health Commun 2000;5(2):135–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Meyer A, Coroiu A, Korner A. One-to-one peer support in cancer care: a review of scholarship published between 2007 and 2014. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2015;24 (3):299–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Hoey LM, Ieropoli SC, White VM, Jefford M. Systematic review of peer-support programs for people with cancer. Patient Educ Couns 2008;70(3):315–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Helgeson VS, Cohen S, Schulz R, Yasko J. Group support interventions for women with breast cancer: who benefits from what? Health Psychol 2000;19(2):107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Lee MK, Suh SR. Effects of peer-led interventions for patients with cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum 2018;45(2):217–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Zhang S, O’Carroll Bantum E, Owen J, Bakken S, Elhadad N. Online cancer communities as informatics intervention for social support: conceptualization, characterization, and impact. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2017;24(2):451–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, Pingree S, et al. Effect of computer support on younger women with breast cancer. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(7):435–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].McCaughan E, Parahoo K, Hueter I, Northouse L, Bradbury I. Online support groups for women with breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;3:CD011652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Salzer MS, Palmer SC, Kaplan K, et al. A randomized, controlled study of internet peer-to-peer interactions among women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2010;19(4):441–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Han CJ, Lee YJ, Demiris G. Interventions using social media for cancer prevention and management: a systematic review. Cancer Nurs 2018;41(6):E19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Prochaska JJ, Coughlin SS, Lyons EJ. Social media and mobile technology for cancer prevention and treatment. American society of clinical oncology educational book American society of clinical oncology annual meeting, 37.; 2017. p. 128–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Kornblith AB, Dowell JM, Herndon JE 2nd, et al. Telephone monitoring of distress in patients aged 65 years or older with advanced stage cancer: a cancer and leukemia group B study. Cancer 2006;107(11):2706–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Madden KZaM. Older adults and internet use. Pew Research Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [84].Cornwell B, Schafer MH. Chapter 9 - social networks in later life In: George LK, Ferraro KF, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 8th ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 2016. p. 181–201. [Google Scholar]

- [86].Institute NAfCatA. Caregiving in the U.S.: a focused look at those caring for someone age 50 or older; 2015.

- [87].Cargiving NAf. Cancer caregiving in the U.S. an intense, episodic, and challenging care experience. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/CancerCaregivingReport_FINAL_June-17-2016.pdf. [Published 2016. Accessed April 23, 2019].

- [88].Navaie-Waliser M, Feldman PH, Gould DA, Levine C, Kuerbis AN, Donelan K. When the caregiver needs care: the plight of vulnerable caregivers. Am J Public Health 2002;92(3):409–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Jayani R, Hurria A. Caregivers of older adults with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs 2012;28 (4):221–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Bevans M, Sternberg EM. Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. JAMA 2012;307(4):398–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. Jama 1999;282(23):2215–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Hsu T, Loscalzo M, Ramani R, et al. Are disagreements in caregiver and patient assessment of patient health associated with increased caregiver burden in caregivers of older adults with cancer? Oncologist 2017;22(11):1383–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Kehoe LA, Xu H, Duberstein P, et al. Quality of life of caregivers of older patients with advanced cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(5):969–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Hsu T, Nathwani N, Loscalzo M, et al. Understanding caregiver quality of life in caregivers of hospitalized older adults with cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(5):978–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Mackenzie CR. ‘It is hard for mums to put themselves first’: how mothers diagnosed with breast cancer manage the sociological boundaries between paid work, family and caring for the self. Soc Sci Med 2014;117:96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Parrish MM, Adams S. An exploratory qualitative analysis of the emotional impact of breast cancer and caregiving among older women. Care Manag J 2003;4(4):191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Wright P, Downing A, Morris EJA, et al. Identifying social distress: a cross-sectional survey of social outcomes 12 to 36 months after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 2015;33(30):3423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Bailey EH, Perez M, Aft RL, Liu Y, Schootman M, Jeffe DB. Impact of multiple caregiving roles on elevated depressed mood in early-stage breast cancer patients and same-age controls. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010;121(3):709–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]