Abstract

Background

The current opioid injection drug use epidemic has been associated with an increase in hepatitis C virus infections among women of childbearing age in the United States, but changes in hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections have not been studied.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of HBV statuses among women of childbearing age nationally and by state was conducted, utilizing the Quest Diagnostics database. Rates of HBV in women born before and after the implementation of universal HBV vaccination recommendations were determined.

Results

We identified 8 871 965 women tested for HBV from 2011–2017. Nationally, the annual rate of acute HBV infections was stable, but rates increased in Kentucky, Alabama, and Indiana (P < .03). The national prevalence of new, chronic HBV diagnoses decreased significantly, from 0.83% in 2011 to 0.19% in 2017 (P < .0001), but increased in Mississippi, Kentucky, and West Virginia (P ≤ .05). A declining prevalence of HBV seroprotection was evident over time, especially within the birth-dose cohort (which dropped from 48.5% to 38.5%; P < .0001).

Conclusions

National rates of newly diagnosed acute and chronic HBV infections declined or were stable overall, but increased significantly in specific Appalachian states. The HBV vaccine is effective in decreasing infections, but seroprotection wanes over time. These trends in new infections may be related to increased injection drug use and highlight potential gaps in HBV vaccine protection.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, hepatitis B exposure, hepatitis B vaccination, reproductive age, testing

In a retrospective analysis, rates of hepatitis B virus among US women of childbearing age were stable or declining nationally, but rising in certain Appalachian states. Birth and adolescent dose vaccine recommendations appeared effective in decreasing infection rates.

Over the past decade, the hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence among women of childbearing age (15 to 44 years) has increased across the United States, and this has been largely attributed to the rise in the opioid injection drug use (IDU) epidemic [1, 2]. As IDU is also a risk factor for hepatitis B virus (HBV) transmission, this increase in IDU may also contribute to an increase in HBV infections. Although a perinatal infection is much more likely to cause chronic HBV, compared to an infection acquired in adulthood [3], acute and chronic infections occur in adulthood, particularly with repeat exposures and/or in the setting of compromised immunity. In a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), increases in new, acute HBV infections were noted in Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia—3 states heavily impacted by the current opioid epidemic and HCV—and 41% of new infections occurred among females [4]. These findings suggest that an increase in IDU or other risk behaviors is leading to a resurgence of acute HBV infections. According to the CDC, the highest incidence of acute HBV infections in 2015 was among persons 30 to 39 years old, with 30.3% reporting IDU as a risk factor [5].

Women of childbearing age represent a priority group for HBV viral elimination efforts, due to the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HBV [6]. Higher rates of acute and chronic HBV among women of childbearing age may increase the rates of chronic HBV among infants. However, hepatitis B is a vaccine-preventable disease; the vaccine has proven safe, as well as highly immunogenic, since it was introduced in 1981 [7]. Universal infant hepatitis B vaccination was implemented by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice (ACIP) in the United States in 1991 [8], resulting in a 75% decrease in the incidences of acute HBV across the country. In October 1997, the ACIP further recommended the vaccination of all previously unvaccinated children under the age of 19 [9]. Although antibody titers may wane over time, immune memory is thought to persist, and booster doses are not routinely recommended in immunocompetent persons [10]. However, women who were vaccinated at birth or during childhood may have a decline in seroprotective titers over time, and 5% of those women may not have responded to an initial vaccination; these women are potentially at an increased risk of acquiring HBV through IDU or sexual exposures.

Although the CDC published HBV data as reported by the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) from 2000 to 2015, there has been no recent, comprehensive, national evaluation of the changing prevalence of HBV, particularly among women of childbearing age, outside of an estimated prevalence by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). We utilized HBV national data from Quest Diagnostics from 2011 to 2017 to address 2 linked objectives: (1) to ascertain whether there had been an increase in HBV among women of childbearing age, as had been reported for HCV, and whether geographical differences were present; and (2) to evaluate HBV seroprotection rates, based the prevailing vaccination recommendations of the era.

DESIGN AND METHODS

The Quest Diagnostics database was used to identify all women aged 15–44 years old in the United States who were tested for HBV from 2011 to 2017. Quest Diagnostics manages the largest database in the United States of deidentified, clinical laboratory data, based on about 45 billion laboratory test results, through which they serve approximately one-third of the US adult population annually and approximately one-half over a 3-year period; specimens are received from an estimated one-half of all physicians and hospitals in the United States [11]. We included women with a result on at least 1 of the following HBV tests: hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb), hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb), hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), hepatitis B e antibody, and HBV DNA. For HBV DNA tests, polymerase chain reaction was used (Cobas 8800, Roche), employing reagents from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN). All other tests were immunoassays (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, Raritan, NJ), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) testing was performed using reagents from Olympus Diagnostic Systems Group (Melville, NY). The results were either reported (for qualitative tests) or classified (for quantitative tests based on numeric values) as positive/detected/reactive or negative/not detected/nonreactive.

We defined 4 clinical sub-classifications of HBV and, within each analysis, each individual was counted only once over the 7-year study period:

Acute HBV infection, defined as being HBsAg positive and, concurrently, either being hepatitis B core immunoglobin M (IgM)–antibody positive or having a serum ALT level >250 U/L. Although false-positive hepatitis B core IgM tests occur, especially in low-risk populations, the presence of a positive HBsAg significantly improves specifity [12].

Chronic HBV infection, defined as either (1) having a positive result on HBsAg, HBeAg, or HBV DNA tests and a concurrent, negative hepatitis B core IgM antibody result; or (2) having 2 positive results on HBsAg, HBeAg, or HBV DNA tests at least 6 months apart (any combination acceptable). Chronic hepatitis B was categorized as a new diagnosis if there were no previous laboratory result(s) indicative of a chronic infection during the study period. A sensitivity analysis was performed to further evaluate incident chronic HBV infections by including patients who had previously tested negative for HBV and became positive during the study period. A second sensitivity analysis that used a more liberal criterion for chronic HBV included all patients who had at least 1 positive HBsAg test and did not necessarily have 2 positive tests 6 months apart.

HBV exposure, defined as being hepatitis B core IgM and/or total core–antibody positive.

HBV vaccine-derived immunity, defined as being HBsAb positive (HBsAb titer ≥ 10 IU/ml) with negative HBcAb.

We defined 3 nonoverlapping birth-era subgroups, based on prevailing HBV vaccination recommendations [8, 13]:

Those in the birth-dose cohort were born in or after 1992 (likely to have been vaccinated at birth);

Those in the adolescent-dose cohort were born in 1980 to 1991 (benefited from the ACIP recommendations in 1997 to vaccinate all children under age 19); and

Those in the partial-vaccination cohort were born prior to 1980 (did not benefit from universal HBV vaccine recommendations).

For state-level analyses, we grouped women based on their reported state of residence. When the state of the patient’s residence was not recorded, the state of the ordering physician was used. Results with missing state data were excluded from specific analyses requiring that element.

The Cochran-Armitage test was used to assess the significance of trends over time, based on 1-sided P values and the 95% confidence limits of Pearson and Spearman correlation estimates. Data analyses were performed using SAS Studio 3.6 on SAS 9.4. (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). This Quest Diagnostics Health Trends report was deemed exempt by the Western Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

A total of 8 871 965 women aged 15–44 years underwent laboratory testing for HBV by Quest Diagnostics from 2011 through 2017 (Figure 1). The partial-vaccination cohort comprised 25.3% (n = 2 247 011), the adolescent-dose cohort comprised 55.1% (n = 4 885 453), and the birth-dose cohort comprised 19.6% (n = 1 739 501). States of residence were available for 8 445 727 women (95.2%).

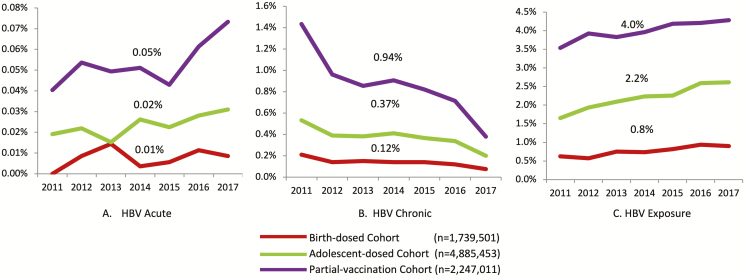

Figure 1.

Rates of (A) acute HBV, (B) chronic HBV, and (C) exposure to HBV among birth-year cohorts, 2011–2017. Abbreviation: HBV, hepatitis B virus.

Acute Hepatitis B Virus Infection

There were 783 women who met the criteria for acute HBV infection: 36 (4.6%) in the birth-dose cohort, 295 (37.6%) in the adolescent-dose cohort, and 452 (57.7%) in the partial-vaccination cohort (Table 1). There were 661 acute HBV patients (84%) who were hepatitis B core IgM–antibody positive; 122 (16%) met the ALT cut-off. The national, annual, acute HBV positivity rate was stable over time (P = .07), although the rate was higher in the partial-vaccination cohort (P < .01) compared to the 2 other vaccine eras (P < .01 for adolescent-dose cohort and P = .2 for birth-dose cohort; Figure 1A).

Table 1.

Acute Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Women of Childbearing Age, 2011–2017

| Test Year | All Women | Birth-dose Cohort | Adolescent-dose Cohort | Partial-vaccination Cohort | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Number of Positive Tests | % | Sample Size | Number of Positive Tests | % | Sample Size | Number of Positive Tests | % | Sample Size | Number of Positive Tests | % | |

| 2011 | 329 092 | 90 | 0.03 | 26 574 | 0 | 0.00 | 151 432 | 29 | 0.02 | 151 086 | 61 | 0.04 |

| 2012 | 325 848 | 110 | 0.03 | 35 104 | 3 | 0.01 | 154 746 | 34 | 0.02 | 135 998 | 73 | 0.05 |

| 2013 | 312 249 | 88 | 0.03 | 41 714 | 6 | 0.01 | 151 135 | 23 | 0.02 | 119 400 | 59 | 0.05 |

| 2014 | 343 140 | 107 | 0.03 | 55 620 | 2 | 0.00 | 168 063 | 44 | 0.03 | 119 457 | 61 | 0.05 |

| 2015 | 368 195 | 94 | 0.03 | 71 774 | 4 | 0.01 | 182 378 | 41 | 0.02 | 114 043 | 49 | 0.04 |

| 2016 | 419 506 | 140 | 0.03 | 97 163 | 11 | 0.01 | 206 705 | 58 | 0.03 | 115 638 | 71 | 0.06 |

| 2017 | 436 569 | 154 | 0.04 | 117 285 | 10 | 0.01 | 212 828 | 66 | 0.03 | 106 456 | 78 | 0.07 |

| Total | 2 534 599 | 783 | 0.03 | 445 234 | 36 | 0.01 | 1 227 287 | 295 | 0.02 | 862 078 | 452 | 0.05 |

Acute infection was defined as a hepatitis B surface antigen and, concurrently, either a hepatitis B core immunoglobin M antibody or a serum alanine aminotransferase ≥250 U/L.

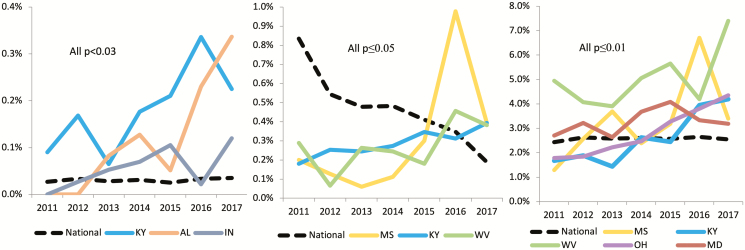

When state-specific rates were examined, Kentucky, Alabama, and Indiana were the only states with significantly increasing trends over the 7-year study period (all P values < .03; Figure 2A). No other state demonstrated a significant increase (state-specific data are provided in Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2.

National rate versus states with opposing trends over 2011–2017, for (A) acute HBV infection, (B) chronic HBV infection, and (C) HBV exposure. Abbreviations: AL, Alabama; HBV, hepatitis B virus; IN, Indiana; KY, Kentucky; MD, Maryland; MS, Mississippi; OH, Ohio; WV, West Virginia.

Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection

A total of 37 755 women met the criteria for a diagnosis of chronic HBV from 2011 to 2017 (Table 2). Nationally, there was a 77% decline in the rate of new chronic infections, from 0.83% in 2011 to 0.19% in 2017 (P < .0001). A decrease over time was observed in all 3 vaccine-era cohorts (all P values < .0001; Figure 1B). Both sensitivity analyses with alternate definitions for chronic HBV infection demonstrated similar trends (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Significant increases in chronic HBV infections were only observed in Mississippi (0.20% to 0.39%), Kentucky (0.18% to 0.39%), and West Virginia (0.29% to 0.38%; all P values ≤ .05; Figure 2B; Supplementary Table 4).

Table 2.

Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Women of Childbearing Age, 2011–2017

| Test Year | All Women | Birth-dose Cohort | Adolescent-dose Cohort | Partial-vaccination Cohort | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Number of Positive Tests | % | Sample Size | Number of Positive Tests | % | Sample Size | Number of Positive Tests | % | Sample Size | Number of Positive Tests | % | |

| 2011 | 1 221 534 | 10 191 | 0.83 | 98 472 | 205 | 0.21 | 678 785 | 3616 | 0.53 | 444 277 | 6370 | 1.43 |

| 2012 | 1 170 897 | 6368 | 0.54 | 131 167 | 183 | 0.14 | 665 304 | 2593 | 0.39 | 374 426 | 3592 | 0.96 |

| 2013 | 1 062 471 | 5083 | 0.48 | 153 846 | 231 | 0.15 | 612 854 | 2328 | 0.38 | 295 771 | 2524 | 0.85 |

| 2014 | 1 058 643 | 5100 | 0.48 | 192 354 | 267 | 0.14 | 607 515 | 2489 | 0.41 | 258 774 | 2344 | 0.91 |

| 2015 | 1 106 327 | 4538 | 0.41 | 246 753 | 346 | 0.14 | 628 680 | 2297 | 0.37 | 230 894 | 1895 | 0.82 |

| 2016 | 1 213 517 | 4213 | 0.35 | 322 456 | 383 | 0.12 | 671 997 | 2269 | 0.34 | 219 064 | 1561 | 0.71 |

| 2017 | 1 201 276 | 2262 | 0.19 | 373 088 | 281 | 0.08 | 641 844 | 1277 | 0.20 | 186 344 | 704 | 0.38 |

| Total | 8 034 665 | 37 755 | 0.47 | 1 518 136 | 1896 | 0.12 | 4 506 979 | 16 869 | 0.37 | 2 009 550 | 18 990 | 0.94 |

Chronic HBV infection was defined by ≥1 laboratory HBV testing to define chronic HBV infection in laboratory criteria (hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B e antigen, and HBV DNA). Abbreviation: HBV, hepatitis B virus.

Hepatitis B Virus Exposure

During the study period, 60 114 women were identified as having HBV exposure (Table 3): 1925 (3.2%) were hepatitis B core IgM positive, and the remaining were total core–antibody positive. Overall, the prevalence of HBV exposure was 2.4% in 2011 and remained at 2.6% for the next 6 years. A small increase over time was observed in each of the 3 vaccine-era cohorts over time (all P < .0001), with the highest rate in the partial-vaccination group (Figure 1C). Over the 7-year study period, 5 states demonstrated a significant increase in HBcAb positivity, including Kentucky (1.7% to 4.2%), Mississippi (1.3% to 3.4%), Ohio (1.8% to 4.4%), Maryland (2.7% to 3.2%), and West Virginia (5.0% to 7.4%; all P values ≤ .01; Figure 2C; Supplementary Table 5).

Table 3.

Exposure to Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Women of Childbearing Age, 2011–2017

| Test Year | All Women | Birth-dose Cohort | Adolescent-dose Cohort | Partial-vaccination Cohort | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Number of Positive Tests | % | Sample Size | Number of Positive Tests | % | Sample Size | Number of Positive Tests | % | Sample Size | Number of Positive Tests | % | |

| 2011 | 308 032 | 7500 | 2.4 | 25 890 | 162 | 0.6 | 140 339 | 2319 | 1.7 | 141 803 | 5019 | 3.5 |

| 2012 | 303 484 | 7979 | 2.6 | 33 572 | 191 | 0.6 | 141 291 | 2739 | 1.9 | 128 621 | 5049 | 3.9 |

| 2013 | 290 629 | 7509 | 2.6 | 40 351 | 302 | 0.7 | 136 364 | 2849 | 2.1 | 113 914 | 4358 | 3.8 |

| 2014 | 315 502 | 8219 | 2.6 | 52 288 | 386 | 0.7 | 150 108 | 3350 | 2.2 | 113 106 | 4483 | 4.0 |

| 2015 | 328 084 | 8446 | 2.6 | 66 721 | 548 | 0.8 | 157 191 | 3541 | 2.3 | 104 172 | 4357 | 4.2 |

| 2016 | 383 859 | 10 166 | 2.6 | 92 501 | 869 | 0.9 | 183 287 | 4753 | 2.6 | 108 071 | 4544 | 4.2 |

| 2017 | 403 389 | 10 295 | 2.6 | 112 055 | 1005 | 0.9 | 190 314 | 4967 | 2.6 | 101 020 | 4323 | 4.3 |

| Total | 2 332 979 | 60 114 | 2.6 | 423 378 | 3463 | 0.8 | 140 339 | 2319 | 1.7 | 141 803 | 5019 | 3.5 |

Exposure to HBV was defined as hepatitis B core immunoglobulin M and/or total core antibody testing.

Hepatitis B Vaccine Immunity

Nationally, 1 123 972 women had ≥1 positive result for HBsAb over the study period; 348 946 women who were HBsAb-positive and tested for HBcAb did not have a concomitant, positive HBcAb result.

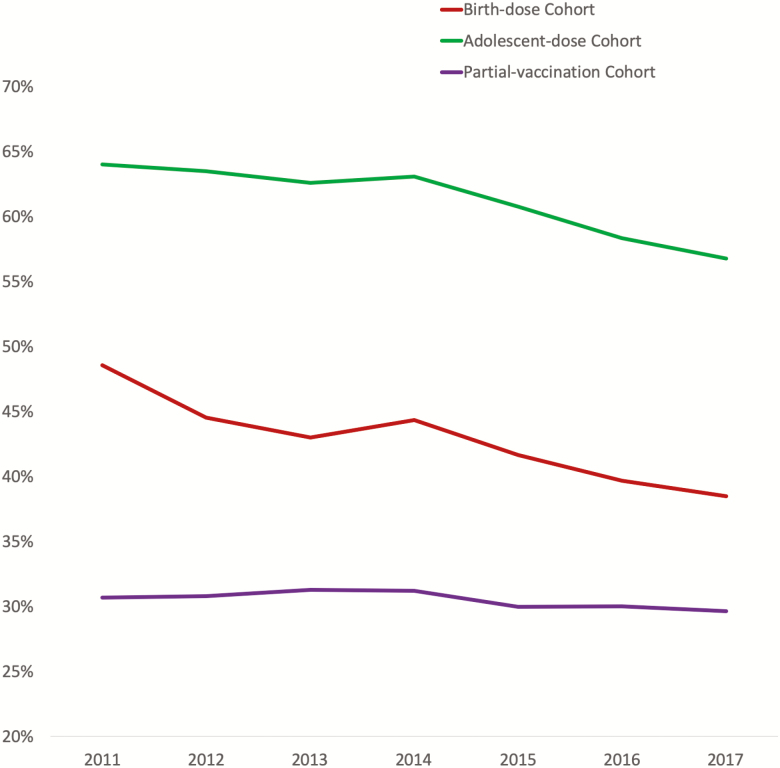

Overall, the rate of vaccine seroprotection was 46.8%. There was a decline in the HBsAb positivity rate over time in all 3 cohorts, with the greatest decline in the birth-dose cohort, which demonstrated a 21.6% decrease (48.5% to 38.5%), followed by a 11.3% decrease (64% to 56.8%) in the adolescent-dose cohort, and a 3.6% decrease (30.7% to 29.6%) in the partial-vaccination cohort (all P values < .0001; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Annual rates of hepatitis B virus vaccine immunity among women of childbearing age in the United States.

DISCUSSION

While we found that the national rates of newly diagnosed acute and chronic HBV infection and exposure to HBV among women of childbearing age either remained stable or decreased nationwide from 2011 to 2017, a state-level analysis revealed increases in specific states in Appalachia. Taken together, these data suggest that in Appalachia, where an increase in HCV cases attributable to IDU has already been seen, there has also been an increase in HBV infections that has not been captured in national figures. When evaluating vaccine effectiveness based on vaccine era, we found consistently higher rates of HBV exposure and acute and chronic infections in the partial-vaccination cohort, compared to the sub-cohorts with universal vaccines, supporting the longstanding protective effects of birth-dose and adolescent-dose vaccinations.

Major strengths of our study are its scale and national scope, providing trends in national and state-specific HBV rates over time. Prior evaluations of the national HBV prevalence have utilized data from NHANES, as well as from the CDC. According to the most recent NHANES evaluation of the HBsAg prevalence from 1999-2016 [14], there was no significant change, with an estimated 0.31% (95% confidence interval 0.23–0.42) of women aged 18–49 years in the United States from 2011–2016 positive for HBsAg. The prevalence of exposure declined from 5.8% in 1999–2000 to 4.7% in 2015–2016.

In comparison to NHANES, where 47 628 adults underwent HBV serology testing, our study evaluated 8 871 965 women, and evaluated a larger portion of the US population [15]. We also evaluated state-level trends, in addition to national figures. We did not exclude data on patients from immigrant and incarcerated populations (1.46% of Quest data were from institutionalized persons, as indicated by the ordering physician’s account information, and included 0.32% of the women in our study).

Our study defined chronic infection, according to the CDC case definition [16], as 2 positive serologic tests 6 months apart, as opposed to a single HBsAg value, as used in NHANES [14]. Despite this more specific HBV definition, the rate of chronic HBV was higher than that of NHANES, at 0.47% overall; NHANES did not report specific rates for women of childbearing age.This suggests that our study population may have included more individuals at higher risk of HBV, such as injection drug users. The prevalence of HBV exposure in NHANES among US-born persons was very similar to that of our cohort, at 2.66% (95% confidence interval 2.13–2.20) in NHANES versus 2.6% in our study, suggesting that our study population likely reflects more US-born persons. Importantly, NHANES represents a screening population, whereas the Quest Diagnostics cohort represents a mixed population, with some patients undergoing screening while others were tested based on a clinical suspicion of infection.

In regards to acute HBV infections, the CDC utilized the NNDSS to evaluate acute HBV over time in 3 key states from 2006 to 2013: Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia [4]. The study reported a stable, national, acute HBV infection rate, but identified a 114% increase among non-Hispanic Whites aged 30–39 years who reported IDU in these 3 states. Other states were not evaluated and, as NNDSS is a passive surveillance system, unreported cases would not be counted. Our study systematically evaluated all states, allowing us to identify increases in acute HBV over time in 3: Kentucky, Alabama, and Indiana. These findings may help inform state-specific planning of HBV vaccination strategies.

The HBV vaccine–associated immunity rate in our study was 46.8% overall, which is higher than the 40.9% rate among US-born women reported by the National Health Interview Survey and similar to NHANES reports from 2011–2014 of a 45.7% rate in individuals aged 20–39 [15, 17]. Our relatively high rate of apparent vaccine coverage may reflect the fact that we studied a specific population—women of childbearing age—with possible enhanced efforts at vaccine coverage for this group. It may also reflect the higher utilization of health resources by women, compared to men [18, 19]. Our results may reflect a patient population that has increased access to care, which may be distinct from the patient population surveyed by NHANES or the patients evaluated by the National Health Interview Survey.

When evaluating the national rates of vaccine seroprotection, we found higher rates in the birth-dose and adolescent-dose cohorts, compared to the partial-vaccination cohort. In parallel, the lowest rates of acute and chronic HBV and exposure to HBV were seen among the birth-dose and adolescent-dose cohorts. These findings clearly demonstrate that recommendations for universal vaccination based on birth year are effective in decreasing the burden of infection. Offering HBV vaccinations to women born prior to 1980 may be a feasible targeted intervention to improve vaccine coverage among those at risk. Recent data suggest that less than one-third of adults aged 18–49 in the United States at risk of infection have HbsAb titers >10 mIU/mL [20], although they may retain immunity, as a booster dose results in a brisk titer increase [21]. In addition, both universal-vaccine cohorts had significant declines in the proportion of women with seroprotective HBsAb titers from 2011 to 2017, while a decline was not seen in the partial-vaccination cohort. A potential explanation for this is that seroprotection may wane over time after birth-dose and adolescent-dose vaccinations, but not if the individual is vaccinated in adulthood. Multiple studies, including in the United States [21], have shown that the infant HBV vaccine series extend protection into adulthood, even if anti–hepatitis B surface levels do not reach the ≥10 IU/mL threshold. Thus, HBsAB titers may not reflect cellular immunity to HBV. However, further study would be helpful to determine whether high-risk adults who received vaccinations at birth or during childhood with waning HBsAb titers would benefit from a booster dose [22].

There are several limitations to our study. Data only captured the results of testing performed by Quest Diagnostics. These data may be affected by ascertainment bias, as women who do not access health care and those with unreported risks may be less likely to be tested for an HBV infection. As indicated in state-specific data in the Supplementary Material Tables, not all states were equally represented, possibly resulting in an asymmetric focus on states that were overrepresented in the database. Quest does not have information on places of birth, so vaccine recommendations in the United States may not have applied to immigrants included in the study. Quest does, however, contain information on race for women who undergo testing during pregnancy; in 2018, there were 5.4% Asian, 17.6% African American, 43.5% Caucasian, 23.5% Hispanic, and 10% unknown/other pregnant women who underwent testing. These percentages closely resemble US Census Bureau data and, therefore, appear to represent the US population [23]. Furthermore, as the states in Appalachia where increases in HBV rates were seen are not among the list of states with high percentages of foreign-born persons [24], it is unlikely that the increases were due to higher influxes of immigrant populations to these states. In addition, the prevalence of HBV in women may have been inflated because providers, especially in areas where the opioid epidemic has been more pronounced, were more likely to screen individuals whom they knew or suspected were at risk of infection. However, when evaluating testing rates over time, although we noted an increase in overall testing rates annually, there was actually a decrease in testing among those aged 15–44, pointing against a selection bias towards testing of this potentially high-risk group (data available). Finally, the frequency of positive HBcAb tests is not truly representative of the national prevalence of exposure, as many individuals may not have been tested for HBcAb by their providers.

In conclusion, we have shown that trends in HBV infection and exposure among reproductive-aged women have been declining nationwide from 2011–2017, but some Appalachian states have experienced significant increases during this period. As the IDU epidemic continues to affect our country, these rates may continue to increase. Maximizing protection against HBV is critical to prevent new HBV infections. In addition to screening during pregnancy, interval screenings for HBV among at-risk women are warranted. HBV seroprotection decreased over time among women who were likely vaccinated at birth and during childhood, and additional studies are needed to determine whether a booster vaccination may be needed, especially among individuals with risk factors such as IDU or higher-risk sex practices.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Jeff S. Radcliff and Edward C. Jones-López (Quest Diagnostics) for valuable editing and assistance with the scientific content of the manuscript.

Financial Support. J. F. is supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (award number 2U54GM104942-02) and NIH/National Institute on Drug Abuse (award number 2UG3DA044825) and has institutional grant support from Gilead. T. K. is supported by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Clinical, Translational, and Outcomes Research Award.

Potential conflicts of interest. T. K. has participated in an advisory board for Gilead. N. A. T. has institutional grant support from Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Merck. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Ly KN, Jiles RB, Teshale EH, Foster MA, Pesano RL, Holmberg SD. Hepatitis C virus infection among reproductive-aged women and children in the United States, 2006 to 2014. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166:775–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koneru A, Nelson N, Hariri S, et al. Increased hepatitis C virus (HCV) detection in women of childbearing age and potential risk for vertical transmission - United States and Kentucky, 2011-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65:705–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Trépo C, Chan HL, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet 2014; 384:2053–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harris AM, Iqbal K, Schillie S, et al. Increases in acute hepatitis B virus infections - Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia, 2006-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65:47–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep 2018; 67:1–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2017. Available at: www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/global-hepatitis-report2017/en/. Accessed 7 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation, US Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B virus: a comprehensive strategy for eliminating transmission in the United States through universal childhood vaccination. Recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 1991; 40(No. RR-13):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: recommendations to prevent hepatitis B virus transmission--United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999; 48:33–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology 2018; 67:1560–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Quest Diagnostics. Fact sheet. Available at: http://newsroom.questdiagnostics.com/index.php?s=30664. Accessed 28 March 2019.

- 12. Chu CM. Immunoglobulin class M anti-hepatitis B core antigen for serodiagnosis of acute hepatitis: pitfalls and recommendations. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 21:789–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Freed GL, Bordley WC, Clark SJ, Konrad TR. Universal hepatitis B immunization of infants: reactions of pediatricians and family physicians over time. Pediatrics 1994; 93:747–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Le MH, Yeo YH, Cheung R, et al. Chronic hepatitis B prevalence among foreign-born and US-born adults in the United States, 1999–2016. Hepatology 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim HS, Rotundo L, Yang JD, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence and awareness of hepatitis B virus infection and immunity in the United States. J Viral Hepat 2017; 24:1052–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Notificable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS). Hepatitis B, Chronic 2012 Case Definition. Available at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/hepatitis-b-chronic/case-definition/2012/. Accessed 15 July 2019.

- 17. Kilmer GA, Barker LK, Ly KN, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination and screening among foreign-born women of reproductive age in the United States: 2013–2015. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:256–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thompson AE, Anisimowicz Y, Miedema B, Hogg W, Wodchis WP, Aubrey-Bassler K. The influence of gender and other patient characteristics on health care-seeking behaviour: a QUALICOPC study. BMC Fam Pract 2016; 17:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bertakis KD, Azari R, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, Robbins JA. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Fam Pract 2000; 49:147–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. King H, Xing J, Dean HD, et al. Trends in prevalence of protective levels of hepatitis B surface antibody among adults aged 18–49 years with risk factors for hepatitis B virus infection-United States, 2003–2014. Clin Infect Dis 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Middleman AB, Baker CJ, Kozinetz CA, et al. Duration of protection after infant hepatitis B vaccination series. Pediatrics 2014; 133:e1500–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hustache S, Moyroud L, Goirand L, Epaulard O. Hepatitis B vaccination status in an at-risk adult population: long-term immunity but insufficient coverage. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2017; 36:1483–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United States Census Bureau: Quick Facts United States. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045218. Accessed 18 April 2019.

- 24.United States Facts - Foreign-Born Population Percentage by State. Available at: https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/united-states/quick-facts/all-states/foreignborn-population-percent#map. Accessed 18 April 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.