Abstract

Introduction

Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) is gaining increasing importance as a medical or cosmetic treatment for various indications. The technology is best suited to the treatment of surfaces such as the skin and is already used in wound care and, in exemplary case studies, the reduction of superficial tumors. Several plasma sources have been reported to affect the skin barrier function and potentially enable drug delivery across or into plasma-treated skin.

Objective

In this study, this effect was quantified for different plasma sources in order to elucidate the influence of voltage rise time, pulse duration, and power density in treatments of full-thickness skin.

Methods

We compared three different dielectric barrier discharges (DBDs) as to their permeabilization efficiency using Franz diffusion cell permeation experiments and measurements of the transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) with full-thickness human excised skin.

Results

We found a significant reduction of the TEER for all three plasma sources. Permeation of the hydrophilic sodium fluorescein molecule was enhanced by a factor of 11.7 (low power) to 41.6 (high power) through µs-pulsed DBD-treated skin. A smaller effect was observed after treatment with the ns-pulsed DBD.

Conclusions

The direct treatment of excised human full-thickness skin with CAP, specifically a DBD, can lead to pore formation and enhances transdermal transport of sodium fluorescein.

Keywords: Transdermal drug delivery, Dielectric barrier discharge, Cold atmospheric plasma, Permeation, Transepithelial electrical resistance, Plasma permeabilization, Plasma medicine

Introduction

Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP), a weakly ionized gas usually produced by the generation of a high electric field, can interact with biological tissues by a combination of several physical and chemical mechanisms [1] without causing extensive tissue heating and burns. Since it is ideally suited to the treatment of surfaces, the fields of plasma medicine and plasma cosmetics often target the skin, healthy or diseased. CAP is already employed in the treatment of chronic wounds [2, 3, 4] and tested for the treatment of superficial tumors [5], warts [6], and many other indications as well as for cosmetic applications, such as skin rejuvenation [7, 8].

When CAP is applied as medical or cosmetic treatment, the efficacy and safety of these treatments need to be critically assessed. Both the permeabilization of skin as well as the retention of the skin barrier function have been observed for different plasma sources and treatments [9, 10, 11]. In several studies an improved penetration or permeation of diverse test substances has been achieved; among the diverse test substances were fluorescently labelled dextran molecules [12], cyclosporine A [13], vitamin D [14], and nucleic acids [15]. While we study plasma permeabilization as a method to facilitate drug delivery, depending on the clinical setting, it might also be an unwanted side effect to be avoided. A reason for this could be to reduce the risk of allergic reactions to penetrating substances or to avoid the penetration of hazardous or allergenic substances or pathogenic microorganisms. Our aim, next to advancing plasma permeabilization as a safe and pain-free method for dermal drug delivery, is the elucidation of its mechanism in order to use or avoid the effect as necessary.

Several different electrode configurations and setups exist for the generation of CAP. Among these are jets and microplasma surface discharges, which treat the skin indirectly, and dielectric barrier discharges (DBDs), which use the skin as a second electrode in order to generate the plasma immediately on the surface. Thus, for direct DBD treatments the skin is directly exposed to the electric field. The ionization of the air above the skin enables electrical current flow and leads to the production of free electrons, ions, and the formation of many other reactive gas species, e.g., OH radicals, ozone, peroxides, and nitric oxides.

Previously, our efforts concentrated primarily on the permeabilization of isolated human stratum corneum [16]. We observed robust pore formation for a filamentary µs-pulsed discharge and suggested a plasma permeabilization mechanism similar to skin electroporation [17]: local joule heating due to increased current flow at sites of filament formation. The potential for electroporation by plasma treatment was previously investigated in silico by computational modeling [18]. Here we report new insights on the permeabilization of excised human full-thickness skin and its quantitative evaluation through the variation of the plasma parameters power density and voltage rise time.

Materials and Methods

Skin Samples and Sample Preparation

Human skin samples were obtained from patients undergoing abdominal or gluteal plastic surgery (Department of Trauma, Orthopedic and Plastic Surgery, University Medical Center Göttingen, Germany). Skin donations by female patients aged between 45‒52 years were collected immediately after the surgery. Subcutaneous fat was removed, and the skin was either used for experiments immediately or frozen in liquid nitrogen or a −80°C solid coolant to be stored subsequently at −20°C. Circular samples of 16-mm diameter were punched out of the freshly prepared or thawed skin and immediately employed in the permeation experiments.

Plasma Sources and Treatment

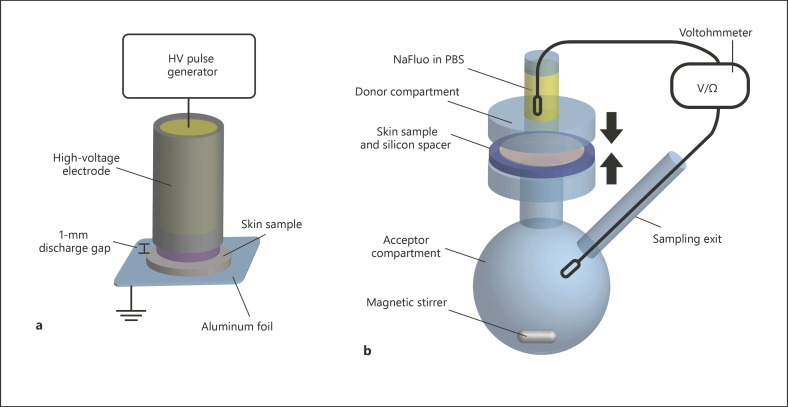

All plasma sources studied here were operated in the direct DBD mode using the skin sample as counter electrode. Different high-voltage sources were used with one electrode setup, which consisted of a cylindrical copper electrode with a diameter of 8 mm covered by an Al2O3 ceramic cylinder of 1-mm wall thickness. Al2O3as dielectric material was chosen because its high dielectric constant leads to a comparably low voltage drop across the dielectric and its good thermal conductivity avoids punctual heating of the electrode during filamentary discharges. The discharges were ignited in ambient air, within the 1-mm gas gap between the electrode and a full-thickness skin sample placed on grounded aluminum foil (Fig. 1a). One plasma treatment consisted of two 90-s intervals with an intermittent pause of 10 min.

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup. a DBD treatment of excised full-thickness skin samples. b Modified Franz diffusion cell and setup for simultaneous TEER measurement and permeation of sodium fluorescein (NaFluo) in PBS.

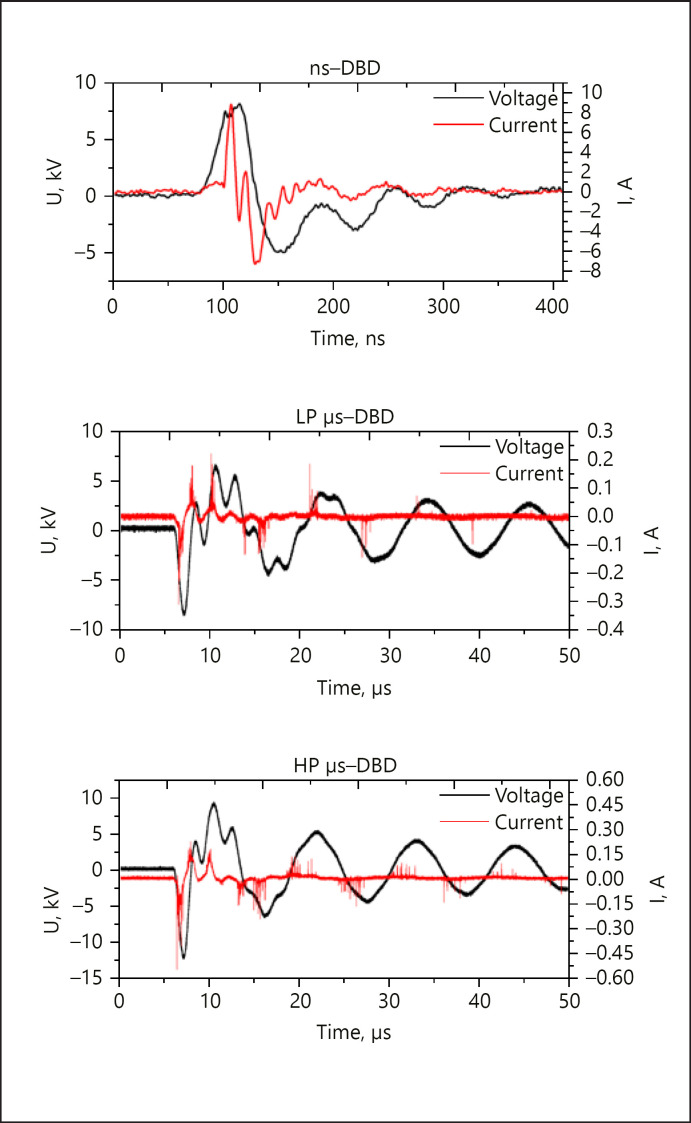

Two µs-pulsed voltage waveforms were generated by the same power supply and differed in voltage amplitude (Fig. 2). The µs-pulsed DBD with lower voltage amplitude (low-power [LP] µs-DBD, max. 9.0 kV) possessed a power density of 334 ± 75 mW × cm−2. The second µs-pulsed DBD (high-power [HP] µs-DBD) was ignited with a higher maximum voltage amplitude of 11.3 kV and a power density of 571 ± 75 mW × cm−2. Additionally, an ns-pulsed DBD was used that had a similar maximum voltage and power density (8.9 kV, 317 ± 39 mW × cm−2) to the LP µs-DBD. The voltage waveforms, all generated at 300 Hz, are AC pulses of a damped sinusoidal shape and have a pulse width (full width at half maximum [FWHM]) of 1 and 5 µs for the µs-DBDs and 28 ns for the ns-DBD (see Fig. 2). The discharges were characterized in detail elsewhere [19]. Power densities were calculated according to the U-I method as the arithmetic mean ± standard deviation of 26‒28 single traces (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Single exemplary voltage pulses (black) and current traces (red) for the three DBDs used in this study: the ns-pulsed DBD (ns-DBD), the low-power µs-pulsed DBD (LP µs-DBD), and the high-power µs-pulsed DBD (HP µs-DBD). Note the different time scales for the ns-DBD and the µs-DBDs.

Franz Diffusion Cell Permeation and Measurement of Transepithelial Electrical Resistance

The quantitative permeation of sodium fluorescein (NaFluo) through excised human full-thickness skin was tested in modified Franz diffusion cells (Fig. 1b). Fresh or thawed full-thickness skin was placed as a barrier between the donor and acceptor compartment immediately after the plasma treatment. To avoid shifting of the skin sample during diffusion cell assembly, silicon rubber rings with an inner diameter of 15 mm and 1-mm thickness were placed around the circular skin samples as a spacer. The 24-h permeation experiment was performed as previously reported [16]. Briefly, the acceptor compartment was filled with PBS and the donor compartment contained 0.5 mL of a solution of 500 µg × mL‒1 sodium fluorescein (Fluka, Cat No. 28,803; 376.27 g × mol‒1) in PBS. To quantify the permeation of fluorescein, 100-µL samples were taken from the sampling exit in the acceptor compartment after 30 min and 2, 12, and 24 h. At the same time, the transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) was measured using an EVOM2 voltmeter with extended range (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) at the beginning and end of a permeation experiment both as a measurement of permeabilization and an indicator for sample quality [20]. The fluorescence intensity in the samples taken from the Franz diffusion cells was quantified using a fluorescence plate reader (Tristar2S; Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany) with excitation at 485 nm (Fig. 1).

Measurement of Peroxide and Nitrate Concentrations

Two relatively stable chemical products of the plasma, peroxide and nitrate, were determined quantitatively with enzymatic test strips and a reflectometer (two-beam spectrometer RQflex 10; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions as reported elsewhere [19]. Immediately after one 90-s DBD treatment of a full-thickness skin sample, a 200-µL drop of water was applied to the skin surface to solubilize the chemical species deposited through reactions in the discharge. Due to the fast inactivation of peroxides on the skin, this compound was always determined as fast as possible. Nitrate measurements were performed afterwards. For the peroxide measurements test strips with a range of 0.2‒20.0 mg × L−1 were used, and for the nitrate measurement the range was 5‒225 mg × L−1. The concentrations in nmol × cm−2 were calculated using the volume of the drop and the effective treatment areas for the three DBDs (0.5 cm2 for the ns-DBD and the LP µs-DBD; 0.78 cm2 for the HP µs-DBD).

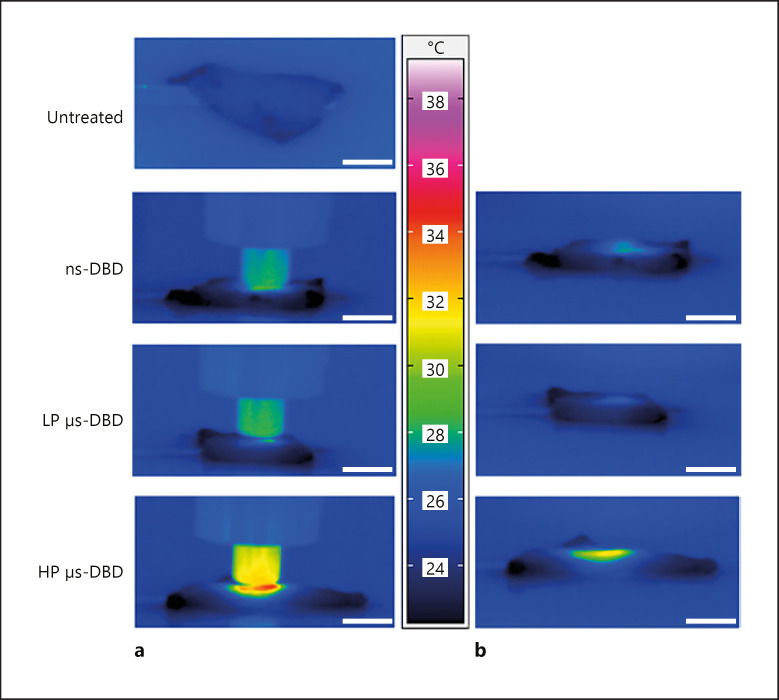

Thermal Imaging

Infrared imaging using a Variocam infrared camera (InfraTec, Dresden, Germany) with Variocam II standard optics assessed the global heating of skin samples during plasma treatment and immediately after the treatment. Images were taken laterally within 1 s after a 90-s DBD treatment or within the last 2 s of a 90-s DBD treatment. Since the emissivity of skin is reported to be 0.98 ± 0.01 [21] and native, hydrated skin samples were used, the emissivity did not need to be corrected for. Image analysis was performed using the software IRBIS 3 professional.

Statistics

All data in this study are expressed as the arithmetic mean ± standard deviation unless noted otherwise. Permeation experiments were performed at least four times for all conditions and included at least four samples in each group for every experiment. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni correction of p values for two-tailed post hoc tests in Origin 2018 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA). Statistical significance was determined at α = 0.05. Data are marked by one asterisk with a p value below 0.05, two asterisks for p < 0.01 and three asterisks for p < 0.001.

Results and Discussion

In our experimental setting, plasma treatments for 2 × 90 s and NaFluo administration were performed consecutively in order to avoid the degradation of the model substance, and in future applications the drug molecules, by the plasma. Additionally, this procedure allows the direct interaction of plasma and skin.

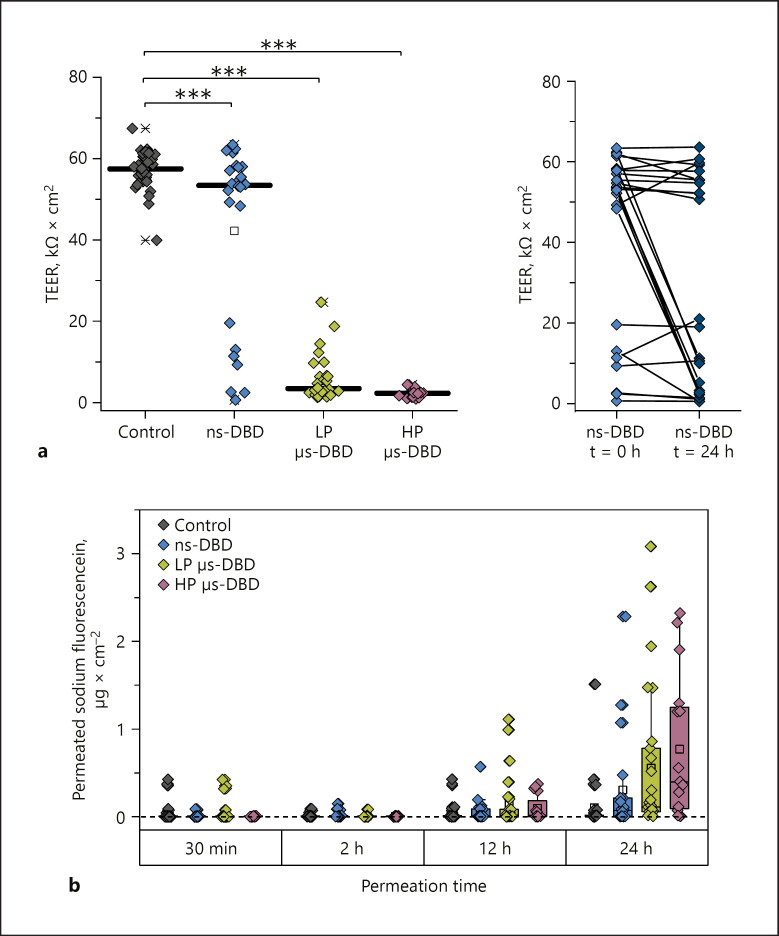

As illustrated in Figure 3a, the plasma treatment of excised human full-thickness skin samples leads to permeabilization and pore formation as characterized by a decreased TEER. This effect is very robust for skin treated with two µs-pulsed DBDs, the LP and HP µs-DBD with FWHM of 1 µs, for which a very filamentary appearance of the discharge is characteristic [19]. For every µs-DBD-treated skin sample, the TEER value lies dramatically below the control samples. The µs-DBD with higher power density (HP µs-DBD) results in even more uniformly decreased TEER values than the µs-DBD with lower power density (LP µs-DBD). However, an impaired barrier function, as shown by decreased TEER, was far less frequently observed after ns-DBD treatment (FWHM 28 ns) even though the ns-DBD and the LP µs-DBD have a very similar power density (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Permeabilization of excised human full-thickness skin by DBD treatment. a Individual TEER values recorded immediately after DBD treatment and before the start of the permeation experiments. The lines indicate the median. n = 16‒34. *** p ≤ 0.001. b Comparison of the TEER values recorded for skin samples treated with the ns-DBD at the beginning of the experiment (t = 0 h) with those recorded at the end (t = 24 h). The “0 h” measurement was performed 15 min after the last plasma treatment. c Progression of the sodium fluorescein (NaFluo) permeation through DBD-treated or untreated full-thickness skin over time. In addition to individual values (n = 16–34), box plots show the median (line) with the 25% and 75% quartiles.

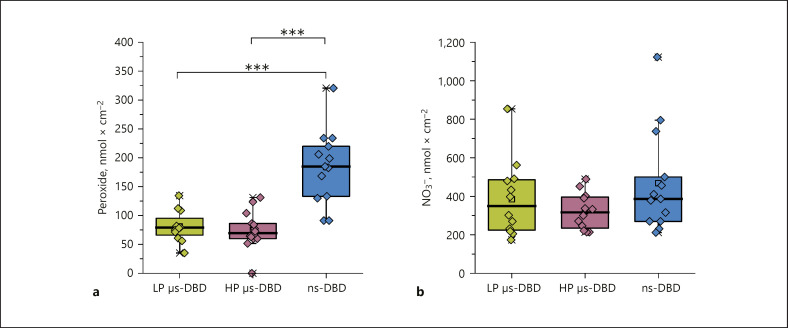

Under ex vivo conditions the pores are stable for at least 24 h as indicated by the continuous, even progressively accelerating, permeation of NaFluo through treated skin (Fig. 3c). The median amount of NaFluo permeated through plasma-treated skin after 24 h is enhanced 4.4-fold for the ns-DBD, 11.7-fold for the LP µs-DBD, and 41.6-fold for the HP µs-DBD. For ns-DBD-treated samples, we often observed that the onset of NaFluo permeation (data not shown) was delayed by several hours. In addition to this, we observed an irregularly delayed decrease of the TEER value for several samples when we compared the values determined at the beginning of the experiments to those taken after 24 h (Fig. 3b). Since the permeabilization usually took place immediately after the µs-DBD treatments, it seems likely that different mechanisms act to produce pore formation in treated skin after µs-DBD treatment compared to ns-DBD treatment. It is possible that in the case of an ns-DBD treatment lipid oxidation is a main contributor towards permeabilization, as has been recently proposed for a different ns-pulsed plasma source [14, 22]. For the µs-DBD treatments, it is possible that lipid oxidation by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species produced in the plasma contributes to the permeabilization and stabilizes the pores [23]. In light of the vastly greater permeabilization effect produced by the LP µs-DBD compared to the ns-DBD, oxidation is not likely to be the major contributor towards plasma-induced pore formation though, especially since the µs-DBD treatment leads to a significantly smaller concentration of peroxides (as indicator for reactive oxygen species) and a slightly lower concentration of nitrate (indicative of the production of reactive nitrogen species) than the ns-DBD treatment (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Chemical species produced on the DBD-treated skin surface. a Peroxide concentration after 90 s of DBD treatment measured inside a 200-µL drop applied immediately after the treatment and given as concentration of H2O2 per 1 cm2 of treated skin. n = 12–14. *** p ≤ 0.001. b Nitrate concentration (NO3−) per 1 cm2 of treated skin measured in the same drop after the peroxide measurement. n = 12–13. For a and b individual values are shown as diamonds. Box plots show the median with the 25% and 75% percentiles, and data outside the whiskers are outliers (coefficient: 1.5) The concentrations of peroxide and nitrate in untreated control samples lie below the detection limit.

Recently, improved wettability of the stratum corneum after cold atmospheric plasma treatment has been proposed as an additional effect to facilitate drug delivery through the skin [24, 25]. While we have not quantitatively studied the water contact angle in our experiments, in accordance with these studies we have qualitatively observed a substantially improved spreading of water droplets after plasma treatments of skin as well.

For µs-pulsed DBDs, in our opinion, the permeabilization can most likely be explained by intense local joule heating at sites of filament formation as these µs-pulsed discharges are characterized by a very filamentary appearance.

The global heating caused by all three plasma treatments barely reaches body temperature for room temperature samples and would not be enough to cause a relevant phase transition of lipids (see infrared photographs in Fig. 5). Moreover, global heating is the same for the ns-DBD and the LP µs-DBD (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Infrared images of skin samples treated with three different DBDs. a Top: the skin sample before treatment has a mean temperature of 25.0°C. Below are images of samples 2 s before the end of a 90-s treatment. The maximum temperature is 28.6°C for the ns-DBD treated skin, 28.3°C for the skin treated with the LP µs-DBD, and 34.5°C for the skin sample treated with the HP µs-DBD. b The same samples shown in a, 1 s after the end of a plasma treatment. The maximum temperature is 27.8°C for the ns-DBD treated skin, 26.5°C for the skin treated with the LP µs-DBD, and 31.6°C for the skin sample treated with the HP µs-DBD. The temperature key in the center belongs to both image sets. Scale bars, 10 mm.

Conclusions

Both the ns- and µs-pulsed DBDs were in principle capable of permeabilizing excised human skin. For the power densities reached with our plasma sources, the filamentary µs-pulsed DBDs were much more effective than the more homogeneous ns-DBD. Since we previously found very little perturbation of the barrier function through ns-DBD treatment of isolated stratum corneum, it was surprising to find a meaningful effect for full-thickness skin treatment. Future experiments will need to address whether the reason for this is indeed an increased lipid oxidation by oxidizing species from the plasma, or if other effects play a role, e.g., the more uneven surface of full-thickness skin might result in increased filamentation of the discharge.

Statement of Ethics

Human skin samples were obtained from patients undergoing abdominal or gluteal plastic surgery (Department of Trauma, Orthopedic and Plastic Surgery, University Medical Center Göttingen, Germany). All donors gave their oral and written informed consent prior to the procedure and the experiments were performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki principles following ethics committee approval.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by a Georg-Christoph-Lichtenberg grant to Monika Gelker through the PhD Program “Processing of poorly soluble drugs at small scale,” funded by Lower Saxony's Ministry of Science and Culture (MWK) and by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (FKZ: 03FH015IX5 and FKZ: 13FH6E01IA).

Author Contributions

M. Gelker: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, visualization, and writing (original draft, review, and editing). C.C. Müller-Goymann: methodology, conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, and writing (review and editing). W. Viöl: conceptualization, project administration, supervision, funding acquisition, and writing (review and editing).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jennifer Ernst and Dr. Gunther Felmerer at the Department of Trauma, Orthopedic and Plastic Surgery of the University Medical Center Göttingen for their continued help with the provision of donated skin. Many thanks are also due to Astrid Ichter for help with the experiments.

References

- 1.Graves DB. Mechanisms of Plasma Medicine: Coupling Plasma Physics, Biochemistry, and Biology. IEEE Trans Radiat Plasma Med Sci. 2017;1((4)):281–92. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heinlin J, Isbary G, Stolz W, Zeman F, Landthaler M, Morfill G, et al. A randomized two-sided placebo-controlled study on the efficacy and safety of atmospheric non-thermal argon plasma for pruritus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Mar;27((3)):324–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brehmer F, Haenssle HA, Daeschlein G, Ahmed R, Pfeiffer S, Görlitz A, et al. Alleviation of chronic venous leg ulcers with a hand-held dielectric barrier discharge plasma generator (PlasmaDerm(®) VU-2010): results of a monocentric, two-armed, open, prospective, randomized and controlled trial ( NCT01415622) J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Jan;29((1)):148–55. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assadian O, Ousey KJ, Daeschlein G, Kramer A, Parker C, Tanner J, et al. Effects and safety of atmospheric low-temperature plasma on bacterial reduction in chronic wounds and wound size reduction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Wound J. 2019 Feb;16((1)):103–11. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuster M, Seebauer C, Rutkowski R, Hauschild A, Podmelle F, Metelmann C, et al. Visible tumor surface response to physical plasma and apoptotic cell kill in head and neck cancer. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016 Sep;44((9)):1445–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman PC, Miller V, Fridman G, Fridman A. Use of cold atmospheric pressure plasma to treat warts: a potential therapeutic option. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019 Jun;44((4)):459–61. doi: 10.1111/ced.13790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi JH, Song YS, Song K, Lee HJ, Hong JW, Kim GC. Skin renewal activity of non-thermal plasma through the activation of β-catenin in keratinocytes. Sci Rep. 2017 Jul;7((1)):6146. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06661-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gentile RD. Cool Atmospheric Plasma (J-Plasma) and New Options for Facial Contouring and Skin Rejuvenation of the Heavy Face and Neck. Facial Plast Surg. 2018 Feb;34((1)):66–74. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1621713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lademann O, Richter H, Meinke MC, Patzelt A, Kramer A, Hinz P, et al. Drug delivery through the skin barrier enhanced by treatment with tissue-tolerable plasma. Exp Dermatol. 2011 Jun;20((6)):488–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimizu K. Biological Effects and Enhancement of Percutaneous Absorption on Skin by Atmospheric Microplasma Irradiation. Plasma Med. 2015;5((2-4)):205–21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nam SH, Choi JH, Song YS, Lee HJ, Hong JW, Kim GC. Improved penetration of wild ginseng extracts into the skin using low-temperature atmospheric pressure plasma. Plasma Sources Sci Technol. 2018;27((4)):44001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalghatgi S, Tsai C, Gray R, Pappas DD. 22nd International Symposium on Plasma Chemistry. Antwerp, Belgium: 2015. Transdermal drug delivery using cold plasmas. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristof J, Miyamoto H, Tran AN, Blajan M, Shimizu K. Feasibility of transdermal delivery of Cyclosporine A using plasma discharges. Biointerphases. 2017;12:02B402. doi: 10.1116/1.4982826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van der Paal J, Fridman G, Fridman A, Neyts EC, Bogaerts A. 4th International Workshop on Plasma for Cancer Treatment (IWPCT-2017) Paris, Institut Curie,: 2017. In search of the plasmaporation mechanism during plasma treatment of skin. 4th International Workshop on Plasma for Cancer Treatment (IWPCT-2017) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connolly RJ, Lopez GA, Hoff AM, Jaroszeski MJ. Plasma facilitated delivery of DNA to skin. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009 Dec;104((5)):1034–40. doi: 10.1002/bit.22451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelker M, Müller-Goymann CC, Viöl W. Permeabilization of human stratum corneum and full-thickness skin samples by a direct dielectric barrier discharge. Clin Plasma Med. 2018;9:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pliquett UF, Zewert TE, Chen T, Langer R, Weaver JC. Imaging of fluorescent molecule and small ion transport through human stratum corneum during high voltage pulsing: localized transport regions are involved. Biophys Chem. 1996 Jan;58((1-2)):185–204. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(95)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babaeva NY, Kushner MJ. Intracellular electric fields produced by dielectric barrier discharge treatment of skin. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2010;43((18)):185206. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gelker M, Mrotzek J, Ichter A, Müller-Goymann CC, Viöl W. Influence of pulse characteristics and power density on stratum corneum permeabilization by dielectric barrier discharge. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2019;1863((10)):1513–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guth K, Schäfer-Korting M, Fabian E, Landsiedel R, van Ravenzwaay B. Suitability of skin integrity tests for dermal absorption studies in vitro. Toxicol In Vitro. 2015 Feb;29((1)):113–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steketee J. Spectral emissivity of skin and pericardium. Phys Med Biol. 1973 Sep;18((5)):686–94. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/18/5/307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van der Paal J, Fridman G, Bogaerts A. Ceramide cross‐linking leads to pore formation: potential mechanism behind CAP enhancement of transdermal drug delivery. Plasma Process Polym. 2019;208:23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yusupov M, Van der Paal J, Neyts EC, Bogaerts A. Synergistic effect of electric field and lipid oxidation on the permeability of cell membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta, Gen Subj. 2017 Apr;1861((4)):839–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kristof J, Aoshima T, Blajan M, Shimizu K. Surface modification of stratum corneum for drug delivery and skin care by microplasma discharge treatment. Plasma Sci Technol. 2019;21((6)):64001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Athanasopoulos D, Svarnas P, Ladas S, Kennou S, Koutsoukos P. On the wetting properties of human stratum corneum epidermidis surface exposed to cold atmospheric-pressure pulsed plasma. Appl Phys Lett. 2018;112((21)):213703. [Google Scholar]